Phil Elmore's Blog, page 2

April 26, 2017

Getting Paid as a Working Writer

If you are a working writer, you must be getting paid.

Working “on spec,” or on speculation, means you’re working with the hope that you’ll be able to make some money. A working writer should almost never work on spec if he or she has other options. That’s because every minute you’re not writing blogs about vacuum cleaners for a paying client’s content farm is a minute lost from your work day. It doesn’t matter how proud you are of the word count for your latest chapter or short story. If there’s no reasonable expectation of getting paid for that work in the near term, that time was personal time. It was an indulgence and, while there’s nothing wrong with indulging yourself, that’s not making a living. It is, at best, an investment in your future (especially if you believe strongly in your project). At worst, it’s simply dollars lost from your wallet.

Working “on spec,” or on speculation, means you’re working with the hope that you’ll be able to make some money. A working writer should almost never work on spec if he or she has other options. That’s because every minute you’re not writing blogs about vacuum cleaners for a paying client’s content farm is a minute lost from your work day. It doesn’t matter how proud you are of the word count for your latest chapter or short story. If there’s no reasonable expectation of getting paid for that work in the near term, that time was personal time. It was an indulgence and, while there’s nothing wrong with indulging yourself, that’s not making a living. It is, at best, an investment in your future (especially if you believe strongly in your project). At worst, it’s simply dollars lost from your wallet.

A working writer’s day is all about making cash. I recommend determining your budget within a healthy margin and then dividing that monthly budget by the daily amount you need to make. Every day, ask yourself: Did I hit my minimum today? Am I making or losing money? The flow of cash should be into your wallet, not out of it. Every day you aren’t working is a day’s income that has to be made up elsewhere… and every dollar you spend has to come from somewhere. As a working writer, your wallet is your master. It is an angry deity. It must be appeased daily.

When you are tempted to spend time writing about writing, indulging in your blog or in any other activity that is not driven by a paying client, understand that this is personal activity and not work activity. You don’t get to spend the day in a Starbucks blogging about how to craft interesting characters and then proudly look back on your day’s “work.” That was a day spent navel-gazing about your craft. Unless you monetize that blog by including it in a book about writing that you then sell, you’ve wasted your time.

This attitude toward making money must pervade everything you do. I had a Kung Fu instructor once who was, of necessity, a small business operator. He had a saying: “Too f–ing nice is too f–ing poor.” You must focus on client development and cultivation, yes (never forgetting that every client has a life-cycle). This requires a certain amount of diplomacy, but you must also be firm. This means that a client who cannot respect the need for timely payment cannot be trusted… and will eventually stiff you.

You’ll need to examine this on a case by case basis. If you have a history of late deliveries with a client (and every writer has done this), that client has earned more latitude. Where a problem exists is when getting paid for your work becomes like pulling teeth. A client who repeatedly strings you along and makes you ask after payment again and again is showing you that he does not respect you. He will continue to take advantage of you — and continue to delay payment — on future jobs. When this happens, he has become a client you can’t afford. Indulging yourself is one thing; getting stiffed is quite another.

Very early in my career, I did some work for a client overseas. I did the work with the expectation of payment on completion. When I delivered, the client didn’t pay. I had password-locked the files and the client asked for the password. Stupidly, I provided it… and never saw a dime for my work. It was the first and only time in my career I have made nothing on a paid job. After that, I insisted on half up front, half on delivery (for those jobs that were not simply prepaid). The logic was that even if I got stiffed on the completion payment, I’d have made something on the job.

I learned my lesson. I was “too f–ing nice” to that client, so I ended up — on that job — “too f–ing poor.” Now, if a client makes me jump through hoops to get paid, I refuse future work. This is the reason I no longer work through Fiverr.com, even though the site was for quite some time a very lucrative source of small jobs. When the company encountered a mysterious “error” that caused a portion of my held payments to disappear, I complained repeatedly. While I’m reasonably confident all my money was eventually re-deposited in my account (and withdrawn by me), the error was unforgivable. If I could not reasonably be expected to get paid promptly for my work through Fiverr, I could not justify the time spent.

You must apply this attitude to all your paying clients. If they pay you within a reasonable time, and especially if they allow you leeway with deliveries, you can cultivate strong relationships with them. There will be those clients whom you know are “good for it,” for whom you can work on little more than a handshake (even though that’s risky). A client who proves you cannot trust him to pay you, however, should not be your client at all. Refuse future work from that client and spend your time working to get paid.

April 21, 2017

The History of Fidget Toys

It all started with torqbars. Or maybe it was tops. It was definitely furthered with fidget cubes and spinners. And now everybody sells them, even your local grocery store.

I’m talking about fidget toys.

Let me start by explaining that “Torqbar” is a patent-pending , registered trademark product from MD Engineering, LLC (formerly SCAM Design). The popularity of this product has spawned a flood of copycat products, not to mention some outright copies. It was created by one Scott McCoskery and is nothing more or less than a weighted spinning widget that does… nothing.

The Origins of Today’s EDC Spinners

McCoskery created a gofundme.com account in 2015 that raised only $4,000 USD of a $15,000 USD goal. “I’m Scott McCoskery, SCAM Design is my label, and the Torqbar is my first product,” he wrote. “I’m overwhelmed by the interest level and want to get them in people’s hands as quickly as possible. I can’t deliver the quantity and quality to meet demand with my current CNC mill. I’ve started this campaign to help me fund a new mill that will increase my production time at least 5x. This means you can get your Torqbar much sooner and with even better precision. Donations will be applied as a credit towards your order, just like a deposit. Thank you for helping me make this 2 year long project a success!”

The implication is that the torqbar first hit the scene, at least in a substantive way, sometime around 2013 or 2014 — and was definitely a known quantity by 2015. It probably got the ball rolling — er, spinning — where EDC fidget toys are concerned. It’s one of the first ones I remember hearing about. As I recall, I actually had to search for “torque bars” online because I couldn’t figure out what it did. People in the EDC community, people obsessed with gear and gadgets and the toting thereof, were paying premium prices for these things. Were they some weapon whose purpose I could not divine? What did they do? Over and over again I learned the same thing.

They do nothing.

Well, that’s not fair. They spin. That’s the attraction of the torqbar. While it was a high-quality product, it was also hindered by the fact that it was very expensive. When your product costs as much as some quality folding knives, you are limiting your audience. The Chinese-made copycats that have flooded the market since, some of which look exactly like torqbars, lack the fit and finish of McCoskery’s original. Most people, however, will gladly sacrifice the smoother spin of a premium product if they can pay six dollars at their local grocery store for something that is almost the same. So it is with the “fidget spinner,” the generic name applied to all manner of spinning toys. Some are more closely modeled after the torqbar than others. One popular variant is a three-limbed spinner.

The genie was well out of the bottle by 2015. In the summer of 2016, a Kickstarter campaign raised an astonishing six million USD for the “fidget cube.” Arguably even more useless than a torqbar or fidget spinner, the cube doesn’t even spin. It’s a “desktop toy” covered in switches and buttons. The user can mindlessly poke away at the toy while trapped in a meeting or stranded inside a cubicle. That is the limit of its function. People love it. Like McCoskery’s torqbar, copies of the fidget cube are everywhere, churned out by Chinese manufacturing interests who treat copyright law as more of a general guideline than a rule.

The History of Fidget Toys

I’ve been told that spinning tops were popular among EDC community members before the torqbar hit the scene. That makes a certain amount of sense, as McCoskery probably took his inspiration from somewhere. Precision metal spinning “pocket tops” seem to proliferate in dated Google Searches around 2014, particularly on the craft site Etsy. But the greater concept of “fidget toys” goes back father. The earliest references I found online were almost 15 years old, which means the concept goes back father than that.

In 2003, Amy Fuselier wrote that children on the autism spectrum frequently have difficulty filtering sensory input. She refers to “sensory accommodations” as one means of regulating and even decreasing negative reactions to sensory input. One of the “accommodations” she cited was fidget toys. Also in 2003, the Center of Development Pediatric Therapies website included a reference to fidget toys as a means of behavioral therapy. “If we were business executives we would call them ‘stress toys,” the site reads. “Fidgets (and stress toys) really do de-stress the body and help increase focus and attention. Fidgets have particular properties that intrigue our sensory systems.” These properties include interesting tactile composition, heaviness or pliability, movement opportunities, and a relatively small size that makes the toy handy enough to keep in a pocket.

Sound familiar? It describes the current wave of fidget cubes and fidget spinners to a tee. By 2005 one finds references online to fidget toys as a developmental tool, useful for treating sensory processing disorder. Three years later, Gizmodo covered a USB-powered fidget toy “designed to replace doodling as a time-wasting activity in the office… The game’s bleeping and repetitiveness may either de-stress you, or distress you: but you’ll have to find that out for yourself.”

By 2011, fidget toys were well established as a means of treating those with sensory input issues. Katie Wetherbee asked whether they really “work” to help students focus and manage behavior in a blog posted that year. “Special education professionals agree that the effectiveness of fidget toys largely depends on the needs of the child,” she writes, going on to cite Dr. Sherri McClurg. “[Dr. McClurg explains that] fidget toys may fill a sensory need for students on the spectrum, and also can reduce tension and nervousness in kids who struggle with anxiety. Students with ADHD, however, may become focused on the fidget toy to the exclusion of the class discussion or activity.” Also in 2011, the Friendship Circle blog defined fidget toys as “self-regulation tools to help with focus, attention, calming, and active listening.” The upshot seems to be that the toy might help you focus and might reduce your stress… or might simply become something you’re obsessed with playing with. I imagine that’s true for kids on the spectrum just as it is for adults trapped in office work that bores them.

Who Needs Fidget Toys?

Five years ago, fidget toys were being touted as a means of helping those with Aspergers, ADHD, and other special needs. Hanna Bogen (a speech-language pathologist and social-cognitive specialist in Los Angeles, CA) wrote about the “fidget toy awakening,” saying that “the gist of a fidget toy is to be something that keeps a person’s hands engaged so they can keep their brain focused on what’s happening around them. They can be great little sensory supports for kids who need constant movement or pressure on their hands, and can aid in helping these kids with whole body listening (minus the perfectly quiet hands part).” Craig Kendall, author of The Asperger’s Syndrome Survival Guide, wrote in 2012 that “Fidget toys are anything that can help regulate your child’s sensory system. Fidget toys as an autism treatment have been around a long time. Sometimes they are some sort of plastic toy in your child’s hand, distracting them and their brain so that they can concentrate. Other times it’s something squishy, something that makes clickety noises [sic], or something that requires tactile manipulation to move or put back together.”

Just three years later, with the fidget toy beginning to creep from the realm of special-needs treatment to knife hobbyists, gadgeteers, and other gear fanatics, The Atlantic’s Julie Beck wrote that stress toys “might boost attention and memory.” A year after that, RJ Scofield speculated that fidget toys could help school kids who have trouble concentrating, and a year after that — just this past March, in fact — Dugan Arnett said in the Boston Globe that “there’s another trend getting traction: fidget toys.” He characterized them as “small, mindless, hand-held gadgets meant to harness nervous energy by giving people something to fiddle with.”

It took until 2017 to get it in print, but that’s probably the best definition of a fidget toy in today’s consumer landscape. Yes, it may help those with special needs, and has been known to do so for some time… but for the majority of the buying public, it’s simply a useless gadget that burns bored or nervous energy. As of this writing, in fact, the fidget spinner is selling out in grocery stores and has become wildly popular among grade-school students.

The fidget spinner is the toy to have for people of all ages… but that’s all it is. It’s not a lifestyle. It’s not a piece of everyday carry gear. It’s not a status symbol or the “iPhone of desktop toys.” It’s an utterly useless gadget that does nothing… and unless you suffer from sensory issues, there’s probably no reason you need one.

None of this, of course, explains why it’s so hard to stop playing with them.

Stop with the Fidget Toys Already

It all started with torqbars. Or maybe it was tops. It was definitely furthered with fidget cubes and spinners. And now everybody sells them, even your local grocery store.

I’m talking about fidget toys.

Let me start by explaining that “Torqbar” is a patent-pending , registered trademark product from MD Engineering, LLC (formerly SCAM Design). The popularity of this product has spawned a flood of copycat products, not to mention some outright copies. It was created by one Scott McCoskery and is nothing more or less than a weighted spinning widget that does… nothing.

The Origins of Today’s EDC Spinners

McCoskery created a gofundme.com account in 2015 that raised only $4,000 USD of a $15,000 USD goal. “I’m Scott McCoskery, SCAM Design is my label, and the Torqbar is my first product,” he wrote. “I’m overwhelmed by the interest level and want to get them in people’s hands as quickly as possible. I can’t deliver the quantity and quality to meet demand with my current CNC mill. I’ve started this campaign to help me fund a new mill that will increase my production time at least 5x. This means you can get your Torqbar much sooner and with even better precision. Donations will be applied as a credit towards your order, just like a deposit. Thank you for helping me make this 2 year long project a success!”

The implication is that the torqbar first hit the scene, at least in a substantive way, sometime around 2013 or 2014 — and was definitely a known quantity by 2015. It probably got the ball rolling — er, spinning — where EDC fidget toys are concerned. It’s one of the first ones I remember hearing about. As I recall, I actually had to search for “torque bars” online because I couldn’t figure out what it did. People in the EDC community, people obsessed with gear and gadgets and the toting thereof, were paying premium prices for these things. Were they some weapon whose purpose I could not divine? What did they do? Over and over again I learned the same thing.

They do nothing.

Well, that’s not fair. They spin. That’s the attraction of the torqbar. While it was a high-quality product, it was also hindered by the fact that it was very expensive. When your product costs as much as some quality folding knives, you are limiting your audience. The Chinese-made copycats that have flooded the market since, some of which look exactly like torqbars, lack the fit and finish of McCoskery’s original. Most people, however, will gladly sacrifice the smoother spin of a premium product if they can pay six dollars at their local grocery store for something that is almost the same. So it is with the “fidget spinner,” the generic name applied to all manner of spinning toys. Some are more closely modeled after the torqbar than others. One popular variant is a three-limbed spinner.

The genie was well out of the bottle by 2015. In the summer of 2016, a Kickstarter campaign raised an astonishing six million USD for the “fidget cube.” Arguably even more useless than a torqbar or fidget spinner, the cube doesn’t even spin. It’s a “desktop toy” covered in switches and buttons. The user can mindlessly poke away at the toy while trapped in a meeting or stranded inside a cubicle. That is the limit of its function. People love it. Like McCoskery’s torqbar, copies of the fidget cube are everywhere, churned out by Chinese manufacturing interests who treat copyright law as more of a general guideline than a rule.

The History of Fidget Toys

I’ve been told that spinning tops were popular among EDC community members before the torqbar hit the scene. That makes a certain amount of sense, as McCoskery probably took his inspiration from somewhere. Precision metal spinning “pocket tops” seem to proliferate in dated Google Searches around 2014, particularly on the craft site Etsy. But the greater concept of “fidget toys” goes back father. The earliest references I found online were almost 15 years old, which means the concept goes back father than that.

In 2003, Amy Fuselier wrote that children on the autism spectrum frequently have difficulty filtering sensory input. She refers to “sensory accommodations” as one means of regulating and even decreasing negative reactions to sensory input. One of the “accommodations” she cited was fidget toys. Also in 2003, the Center of Development Pediatric Therapies website included a reference to fidget toys as a means of behavioral therapy. “If we were business executives we would call them ‘stress toys,” the site reads. “Fidgets (and stress toys) really do de-stress the body and help increase focus and attention. Fidgets have particular properties that intrigue our sensory systems.” These properties include interesting tactile composition, heaviness or pliability, movement opportunities, and a relatively small size that makes the toy handy enough to keep in a pocket.

Sound familiar? It describes the current wave of fidget cubes and fidget spinners to a tee. By 2005 one finds references online to fidget toys as a developmental tool, useful for treating sensory processing disorder. Three years later, Gizmodo covered a USB-powered fidget toy “designed to replace doodling as a time-wasting activity in the office… The game’s bleeping and repetitiveness may either de-stress you, or distress you: but you’ll have to find that out for yourself.”

By 2011, fidget toys were well established as a means of treating those with sensory input issues. Katie Wetherbee asked whether they really “work” to help students focus and manage behavior in a blog posted that year. “Special education professionals agree that the effectiveness of fidget toys largely depends on the needs of the child,” she writes, going on to cite Dr. Sherri McClurg. “[Dr. McClurg explains that] fidget toys may fill a sensory need for students on the spectrum, and also can reduce tension and nervousness in kids who struggle with anxiety. Students with ADHD, however, may become focused on the fidget toy to the exclusion of the class discussion or activity.” Also in 2011, the Friendship Circle blog defined fidget toys as “self-regulation tools to help with focus, attention, calming, and active listening.” The upshot seems to be that the toy might help you focus and might reduce your stress… or might simply become something you’re obsessed with playing with. I imagine that’s true for kids on the spectrum just as it is for adults trapped in office work that bores them.

Who Needs Fidget Toys?

Five years ago, fidget toys were being touted as a means of helping those with Aspergers, ADHD, and other special needs. Hanna Bogen (a speech-language pathologist and social-cognitive specialist in Los Angeles, CA) wrote about the “fidget toy awakening,” saying that “the gist of a fidget toy is to be something that keeps a person’s hands engaged so they can keep their brain focused on what’s happening around them. They can be great little sensory supports for kids who need constant movement or pressure on their hands, and can aid in helping these kids with whole body listening (minus the perfectly quiet hands part).” Craig Kendall, author of The Asperger’s Syndrome Survival Guide, wrote in 2012 that “Fidget toys are anything that can help regulate your child’s sensory system. Fidget toys as an autism treatment have been around a long time. Sometimes they are some sort of plastic toy in your child’s hand, distracting them and their brain so that they can concentrate. Other times it’s something squishy, something that makes clickety noises [sic], or something that requires tactile manipulation to move or put back together.”

Just three years later, with the fidget toy beginning to creep from the realm of special-needs treatment to knife hobbyists, gadgeteers, and other gear fanatics, The Atlantic’s Julie Beck wrote that stress toys “might boost attention and memory.” A year after that, RJ Scofield speculated that fidget toys could help school kids who have trouble concentrating, and a year after that — just this past March, in fact — Dugan Arnett said in the Boston Globe that “there’s another trend getting traction: fidget toys.” He characterized them as “small, mindless, hand-held gadgets meant to harness nervous energy by giving people something to fiddle with.”

It took until 2017 to get it in print, but that’s probably the best definition of a fidget toy in today’s consumer landscape. Yes, it may help those with special needs, and has been known to do so for some time… but for the majority of the buying public, it’s simply a useless gadget that burns bored or nervous energy. That’s all it is. It’s not a lifestyle. It’s not a piece of everyday carry gear. It’s not a status symbol or the “iPhone of desktop toys.” It’s an utterly useless gadget that does nothing… and unless you suffer from sensory issues, there’s probably no reason you need one.

None of this, of course, explains why it’s so hard to stop playing with them.

April 4, 2017

The Etiquette of E-Begging

I saw something recently that turned my stomach. A self-published author who has a considerable following took out an ad on social media to promote his latest work. When one of the targeted audience members complained about being spammed, the author became vulgar and insulting.

I saw something recently that turned my stomach. A self-published author who has a considerable following took out an ad on social media to promote his latest work. When one of the targeted audience members complained about being spammed, the author became vulgar and insulting.

This is a lot like trying to hand someone an advertising flier on a public street and, when they tell you not to bug them, screaming “Well, then F— you, buddy!” at the top of your lungs. Now imagine doing that and then following your victim down the street, pointing and shrieking, “That guy’s a humorless a–hole! THAT GUY’S A HUMORLESS A-HOLE.”

But that’s exactly what the author did.

He had a rancorous exchange with the woman in question, then screen-capped it and shared it with his audience. Mercifully, he blocked out her name so she wouldn’t be subjected to harassment from his fans, but that’s all he got right. An author who behaves this way toward his prospective audience doesn’t deserve to sell a single copy of his book.

Advertising on social media, or soliciting funds at all, is always a delicate proposition. There’s a fine line between asking for support and hectoring people for spare change. Most people refer to such calls for financial support as “e-begging” — and they’re not wrong. The idea is that if you have an audience of sufficient size, they’ll have a vested interest in supporting you financially. They’ll give you money so that you can continue providing them a service. They’ll want to support you because the alternative is not to have you. If you can’t live, you can’t write — and the need to balance paying your bills with writing the next great American novel is a dilemma most authors face.

This is why I draw a distinction between working writers and authors. Anyone can write a novel. It takes no money at all to become an author and even to publish your work on certain platforms. But to make a living from your writing requires a lot more work, a lot more hustle, a lot more late nights… and a fine understanding of the etiquette of e-begging.

Simply put, you cannot afford ever to forget that you are begging people for money when you ask for funds. Whether you do that as part of a crowdfunding campaign, in the form of social media advertising, or in some other solicitation does not matter. However you put the request before the eyes of your audience, you are holding out your hat and hoping they drop some money in it.

Forgetting this leads to arrogance and entitlement. An author who thinks he deserves your money — and that any negative feedback, any nasty comment, any vocal refusal to buy his product, should be met with scorn and derision — deserves to starve. Worse, he deserves to go back to… his day job. If he has the gall to mistreat people who react negatively to his begging, he is saying to you, “I am entitled to your cash.” But he isn’t. No beggar deserves a dollar, spare or otherwise. Asking people for their patronage is always asking for charity.

I can speak from experience. A few months ago I successfully crowdfunded the writing of a parody action novel, Spaceking Superpolice. That novel, which I’m now in the process of editing and laying out for publication, would not exist if not for the charity of my audience. If I choose to take out advertising on social media to sell this book — a sticky proposition at the best of times, because people get testy when they see unwanted posts and commercials in their timelines — I must be on my best behavior. The best response to a negative reaction is either a polite explanation or no response at all. It is never a vicious retort. That’s not just undignified and unprofessional; it’s the kind of thing that should get your social media page shut down. It’s the type of childish response that amateurs make. It is not the conduct of a professional who is worthy of his audience’s hard-earned cash.

I can speak from experience. A few months ago I successfully crowdfunded the writing of a parody action novel, Spaceking Superpolice. That novel, which I’m now in the process of editing and laying out for publication, would not exist if not for the charity of my audience. If I choose to take out advertising on social media to sell this book — a sticky proposition at the best of times, because people get testy when they see unwanted posts and commercials in their timelines — I must be on my best behavior. The best response to a negative reaction is either a polite explanation or no response at all. It is never a vicious retort. That’s not just undignified and unprofessional; it’s the kind of thing that should get your social media page shut down. It’s the type of childish response that amateurs make. It is not the conduct of a professional who is worthy of his audience’s hard-earned cash.

Another author of my acquaintance once told a reader that he hoped the reader’s family would be viciously murdered by rabid dogs. What was the reader’s crime? He got into a political disagreement with the author on Facebook. I can’t imagine the arrogance required to insult someone who has actually spent money to read my work, even if we disagreed about something. Hell, even a bad review isn’t call to wish death on a man’s family. That’s an overreaction on a scale so absurd it sounds made up… but I watched it happen.

Self-promotion isn’t bad. You can’t survive without promoting yourself. Advertising, crowd-funding, and even some good old-fashioned e-begging are all useful tools for keeping the wolf from the door. They must always be kept in perspective, however. You must never lose sight of the fact that patronage is, on some level, charity. Yes, you are exchanging value for value — but authors are worth less than bass players in Han Dold City. Nobody with money has ever said to himself, “I need a writer? Where am I going to find one of those?”

You can’t throw a half-finished Cafe Mocha out the front door of a Starbucks without hitting at least three writers. You are replaceable — and there’s plenty of competition for you what you do. That means you can’t afford to forget your manners. The next time you take hat in hand to ask your audience to buy your latest masterpiece, remember what you’re doing. Remember that you continue to write, and to eat, because of your clients.

Be they employers or customers, everyone who pays for what you do is a client. These clients form your audience. Be worthy of your audience and they’ll show you the support you truly deserve.

February 9, 2017

Mean Street Graphix: Dye Sublimation Printing That’s Anything But Mean

“Send me your logo,” Keith Miller of Mean Street Graphix told me. That was it; I didn’t give him any instructions. I simply sent him a high-res version of my Internet Gunslinger logo (which was custom designed for me by John “Johnny Atomic” Jackson). The items you see here were the result.

The mug contains an altered version of the design, in which Miller added a shadowed echo of the logo behind it. The other items are a simple reproduction of the logo as originally created.

Miller’s Mean Street Graphix, based in Louisville, Kentucky, specializes in dye sublimation transfers. This is a process of printing a high-resolution image with a special dye solvent ink on transfer paper. They then apply heat and pressure to the image and a pre-treated product (a mug, a sign, a phone case, a key chain, a coaster, etc.). This imprints the picture onto the product.

The process is not printing. It’s not a sticker or an applique. It essentially changes the color of the item’s surface. That means it will never peel, chip, or wipe off. To damage the image, you basically have to scratch the product itself. Dye sublimation printing can be used on a wide array of products and promotional items.

Miller explains that he ran several failing martial arts gyms for many years while learning to make his own graphics, signs, and shirts to save money. After he gave up the gym business, he started a small vinyl and sign business. It was then that he learned about dye sublimation and fell in love with the process. “We still do signs and stuff,” he told me, “but it’s not our main focus anymore.”

In a market saturated with competition, Miller prides himself on personalized service — and the ability to edit a creation for the client’s approval. “You can probably save money by buying a coffee mug or phone case on Etsy or someplace like that,” he admits. “Our process takes longer and requires more work than just clicking ‘Buy Now,’ but it also guarantees you’ll be getting a 100% personalized product.”

Miller has produced a vast array of dye-sub items for his customers, but says the most fun he’s had to date was for a client’s “emoji party.” Each attendee was assigned an emoji and had to dress up as that symbol. “It wasn’t particularly weird,” he says, “but it was fun.”

Mean Street doesn’t actually sell the items its clients purchase; it sells memories, Miller asserts. “We do corporate and small business stuff, but the bulk of our customers are just regular folks,” he told me. “They bring in a picture of their baby that they want it on a tile display, or they want to make a memorial piece for a deceased family member. It makes each job the most important one you’ve ever done. When you hand a mother a personalized dog tag with a picture of the son she lost in Iraq…damn. All I can say is, damn. This is the best, most rewarding job I’ve ever had.”

The biggest challenge facing a company like Mean Street is getting its product out there. While it’s been said that if you build a better mousetrap, the world will beat a path to your door, that doesn’t exactly work if nobody is aware of your innovation. “I’ve got a pretty good damned mouse trap,” says Miller. “But if they don’t know about it, then they don’t know about it.”

With some chagrin, Miller explains that before discovering dye sublimation, he invested nearly ten thousand dollars in printing equipment he doesn’t use… and which he can’t sell because it’s leased. He takes this in stride, however, On the horizon for Mean Street is, he says ,more corporate work, which will help justify opening an actual store front.

“A steady flow of production level work will fund the upstart and monthly operations when gift-giving seasons are slow,” he explains. “We have scouted several locations in the Louisville area that we think would be ideal. We’d like to have a gift shop in the front and a production facility in the back.”

For now, customers interested in purchasing Miller’s products may do so by visiting him online at http://meanstreetgraphix.com, or on Instagram and Facebook. The company can also be reached at 502-438-8682. Miller promises that you will be happy with the work he provides.

“I’m pretty convinced that I don’t have to sell anything we do,” Miller says. “I just need you to see it. It sells itself.”

December 26, 2016

Dealing with Post-Holiday Blues

There are any number of reasons some people feel depressed or stressed leading up to and during the holidays. Feeling lonely because they lack family or romantic connections, feeling overwhelmed, feeling financial pressure, or simply feeling left out as the rest of the world seems to be having a wonderful time with friends and family… these are all very real issues for many of us. Social media exacerbates the problem. Your connections post images of gifts and gatherings, reveling in this time of year, prompting you to compare your own experiences to theirs. And don’t forget that with the days short and the weather oppressive, seasonal depression may also come into play.

The fact is, “the most wonderful time of the year” can be anything but for many of your friends and family… and for you. You’d think the end of the holidays would lead to relief for those affected, but this isn’t always the case. Often, the let-down after Christmas and the New Year are past can be even worse, intensifying the feelings of depression that some feel between December and January. So what can you do to prevent feeling bad during this time of year… or to feel better if you’re already down? Here are four suggestions.

Avoid Bitter Social Media Posts

Every one of us has turned to social media to vent about the things that bother us. We hope to receive support and even sympathy from our connections. For those most part, we’ll get just that, at least from those who choose to respond. Overwhelmingly, though, your connections will perceive your holiday venting as whining. It will diminish you in their eyes, making you look weak, or simply annoying those who are enjoying the afterglow of Christmas and New Year’s. This is not to say your feelings are not valid; they are. But you do yourself more harm than good by sharing those complaints. A diary or journal — or an anonymous blog — are the best places for writing these types of bitter thoughts. Publicly attaching these complaints to your real identity, on the other hand, makes your social media contacts see you as passive-aggressive at best… and a Grinch at worst.

Get Through It, Then Get Organized

The best way to clear out feelings of stress, depression, and the holiday blues is to get organized. There’s no avoiding the feelings the holidays may bring while they’re happening; you’re just going to have to endure those. But once you find yourself in the holidays’ wake, take advantage of any extra downtime to clear the decks of old business and straighten your work spaces. Clean up, organize, and position yourself for a productive new year. Never underestimate the psychological benefit of a freshly cleaned and organized work area to re-frame your mental state. If your area is orderly, your thoughts will be more so.

Do Something — Anything — Productive

The next step, once you’ve steered clear of social media venting and organized your work area, is to get warmed up. Just as an athlete stretches before exerting himself, you can’t jump right into a productive post-holiday period completely cold. Get your mind working, shake off the rust you’ve accumulated over the holidays, and shed the logy feeling brought on by holiday over-eating by getting yourself revved up with a useful, but not particularly difficult, task. (For example, if you’re a writer, you might consider warming up after Christmas by writing an article on beating the holiday blues.) It doesn’t hurt to do some light exercise and get yourself moving again. The hardest step is always the first one.

Set Reasonable Goals and Focus on Achieving Them

All right: You’ve gotten through the holidays. You’ve prevented yourself from venting in a way that will look passive-aggressive. You’ve gotten organized and you’re warmed up mentally and physically. So now what? Well, as a famous man once said, “Without a plan, there’s no attack. Without attack, there’s no victory.” You need to sit down and set specific goals. The problem of “terminal vagueness” — wishing, wanting, or longing for something, with no realistic plan toward achieving that goal — is pervasive in society. It’s not enough to know that you desire something. You have to sit down and assess, honestly, what is required to get it. Only when you understand the specifics can you formulate a plan and then execute that plan.

Setting reasonable goals and going after them gives you something positive to anticipate. It gives you purpose. Most importantly, it fills your mind with productive thoughts rather than depressing distractions. Instead of dwelling on what makes you unhappy, you are focused on what will make you feel fulfilled and achieved. That’s a formula for a great new year… and one that each of us can follow.

If the holidays have you down, if the post-holiday blues have set in, don’t just read these words. Make an honest attempt to put them into practice. You’ll be better off for it.

November 29, 2016

What If My Client Sues Me?

As a working writer, sooner or later, somebody is going to threaten to sue you. This isn’t because you’re a bad person. It isn’t even because you did something wrong. You can do everything right and still end up with an unhappy client. This doesn’t just apply to writers, either. It can affect any small business, whose relationships with legal firms tend to be fleeting and far between.

You may recall that I wrote in No, You Won’t Be Suing Anybody that it is actually quite difficult to sue someone for libel or slander because you got into a disagreement on the Internet. I am not, however, talking about that kind of dispute. To sue for libel, slander, or some other aspect of, “That guy said something mean to me online” requires that you prove damages, which is nearly impossible. The type of lawsuit I’m referring to now, by contrast, has to do with services that have been rendered for money.

When the client is unhappy and asks for his money back, there is a specific amount involved — often one that is low enough that it can be hashed out in small claims court. It’s relatively easy to take someone to court for an amount of a few hundred or even a few thousand dollars. In other words, for the amounts that a working writer is paid for most of his projects, it’s not difficult at all for an angry client to sue to get the money back.

Typically how this works is that you agree to provide some work for somebody else. You provide all or part of that work. The client decides he or she is unhappy and asks for a refund of some or all of the fee paid. If you at any time have told them they get a refund if they’re not satisfied, you have no choice; you must refund the fee. If you’ve not said that, you have some options:

You can refund the money, which you probably don’t have because you spent it already.

You can offer a partial refund and negotiate this with the client.

You can refuse the refund on the grounds that you are out your time and effort, which you can’t get back.

The goal here is not simply to prevent money from flowing in the wrong direction (out of your bank account and back into a client’s wallet). You must, if you value your business, make a good faith effort to salvage the relationship. Businesses don’t thrive by creating enemies. You will only succeed when you develop a constantly rotating stable of clients who send work your way on a repeat basis. This is because…

Work that comes knocking at your door is worth two to three times as much as work you have to pursue.

If you want the work to come find you, you have to develop clients. You can’t develop clients if you lose them and make no attempt to bring them back. I once did some editing work for a third-party client whose project partner kept changing the parameters of the job. I found these conditions untenable and was forced to forfeit my completion payment in exchange for ceasing work on the project.

I was worried I had lost that client, but I was diligent in my efforts and made every effort to be reasonable about it. They remembered that and came to me with different writing work in the future — work that was lucrative and led to more work. You must never burn bridges if you can prevent it. (This is true not just of clients you like, but even of those clients whom you find objectionable. Their money spends as well as anyone else’s.)

So what do you do when a client expresses dissatisfaction and hints they might be willing to sue to get their money back? There are a few things to keep in mind.

1. Offer to Work with Them at a Discount

In my opinion, the first rule of dealing with an unhappy client is always to offer them a discount in order to repair the relationship. I once edited a fantasy novel for an aspiring author. It was a big job and I did more work than I thought I would need to do. In other words, I lost money on the job. But I made every effort to do what was asked of me. Everything was fine until I made the mistake of offering that author some suggestions for how he might improve his work in the future (which I thought was one of the things I was being paid to do for him). He became offended and demanded all of his money back, saying he was not satisfied with the quality of the edit.

I told him that while I was not in a position to offer him his money back, given that I was out my time and effort, I would be happy to take another edit pass at the work for free. I also offered to do additional work on the structure of the book if he was willing to pay to have more work done. I would do so at a significant discount, I promised, up to and including rewriting the entire book.

Some clients will take you up on this offer simply because they want their project to be completed to their satisfaction. That is their primary motivator; they just want the work to be done. When a dissatisfied client accepts this option, and you can work diligently to prove to them you have their best interests in mind, things usually work out for the best. The client is satisfied, your honor is intact, and your reputation is protected.

2. Negotiate a Partial Refund

Sometimes, no matter what you offer, the client is having none of it. He’s lost faith in you, rightly or wrongly, and he just wants to cut his losses and get out. You may choose, for the sake of honor and to prevent making an enemy who’ll badmouth you to other potential clients, to give a partial refund. Choose an amount you can live with that will also satisfy the client, but which leaves you some amount of money for your time and effort. Of course, you can also just give in and return all the money, which means you did all that work for nothing. This is a highly dissatisfying “solution” for you, the writer, because again it is sending money in the wrong direction — out of your account and into your client’s wallet. That’s the opposite of how things are supposed to work, but sometimes it is necessary to salvage a business relationship or to prevent creating enmity.

3. If He Threatens to Sue, STOP TALKING TO HIM

This part is important. If none of your offers make any headway and the client threatens to sue you for the refund, you must stop talking to him directly. Nothing you say at that point will help. If he’s going to sue, you need to communicate with his lawyers through your lawyer. More importantly, making the threat indicates he’s not willing to work things out with you personally.

If a client threatens a lawsuit, I stop talking to that client. Then I wait for a letter to arrive. In most cases, that letter never comes. People threaten to sue all the time and, if they get to the point of actually talking to a lawyer, they realize it will cost as much or more to sue as the amount they hope to recover. Most people will simply let the matter drop.

4. Examine the Demand Letter Carefully

If your client takes the next step, he’ll pay a law firm to put a demand letter on legal letterhead. This will take the form of a letter telling you, “So and so says you owe him money. Pay him money or else.” The or else is the threat of an actual lawsuit filed against you. If the letter says to contact the client directly to pay him, rather than contacting the law firm to arrange for payment, there’s a good chance your client paid a lawyer just enough to get his letter on their letterhead. In other words, he’s hoping the threat of the lawsuit makes you give in and send the money, but he has no real intention to sue (or the firm has told him there isn’t much chance of actually winning in court).

5. The Worst That Can Happen is You Owe the Money

After you receive the demand letter, there’s a tiny percentage chance that you might get served papers. If you do, don’t panic. People have a phobia about lawsuits, generally. The idea of being sued fills most people with terror. Once you have some understanding of the legal system, a lawsuit should annoy you, not scare you. It’s a huge hassle, but the absolute worst that can happen is that you end up owing the client the money he asked you to refund.

Chances are good that you won’t end up owing it, too. If you’ve done diligent work and kept good records of your correspondence with the client, you can establish that you did, in good faith, the work for which you were paid. That will go a long way towards winning a small claims case if it does come to that… which it most likely won’t.

The goal of a working writer, and of any small business, is to develop clients and expand one’s client base. Leaving a trail of dissatisfied clients behind you, especially clients who threaten to sue, is no way to run a business. Despite your best efforts, however, it could happen to you. If it does, keep these guidelines in mind and proceed accordingly. You’ll be surprised how often things work out in your favor.

August 16, 2016

If You Can’t Handle Bad Reviews, You’re a Bad Writer

I still remember the first time I got a negative review on one of my works of fiction. It was one of my Executioner novels, so the response was reasonably authentic. There was no reason this reader had to dislike me as a person, nor was the subject matter of my book in any way controversial. Non-fiction books frequently suffer negative reviews for ideological reasons, so when a book like that gets panned, you can tell yourself the reviewer simply doesn’t like your opinions. When somebody tells you they hate your fiction, it’s a lot more like they’re saying they hate you. This can be difficult for authors to accept.

There’s a practical reason to get upset about negative reviews, of course, and that is that damned star rating next to the title. We all look at that star rating, for good or for ill, next to a title on Amazon. We form judgments based on that rating. It doesn’t matter if a deep dive into the comments will reveal a little review-war going on, where many of the reviewers have agendas. I should know; one of my controversial non-fiction books was featured on the website “The Worst Things For Sale.” Shortly before (or after, I can’t remember) that, it was featured on Break.com. Then the cover got made fun of by Chris Hardwick and friends on Comedy Central’s @Midnight. (Obviously, a lot of these joke-writers “borrow” ideas from each other.)

Nobody wants their book to be judged by unfairly negative comments. Everybody wants their work to be taken on its merits and judged accordingly. It would be fair to say some of the reviews that popped up right after the brief public relations explosion for my non-fiction book were from people who had never read it. It’s normal to get upset if you feel your work is being unfairly tagged with a low-ball rating.

But most of the time, when your novel gets a bad review, that’s not what’s happening.

Most of the time, if someone dislikes your fiction, it’s because the reader genuinely didn’t enjoy it. The first time I got a negative review on one of my commercially published action novels, I turned to another writer who wrote for the same mass-market series. He told me something I will always remember: “Online reviews are worth exactly what you pay for them.” But even while you tell yourself that, be careful not to use it as an excuse. Just because some anonymous reader on Amazon read your book and hated it doesn’t mean he or she doesn’t have a valid opinion. Look at the criticisms. Some will be ignorant, sure, and some will be people who the book simply was not written to please. A negative review that starts with, “I don’t like horror fiction” and then trashes your horror fiction book is kind of self-explanatory. But if a reader writes to say your comedy book simply wasn’t funny, or your action novel didn’t grab and hold his attention, you need to look at that. Evaluate it on its own merits. Ask yourself if you can do better.

You may evaluate the criticism honestly and decide that it doesn’t apply. That happens too; some people just don’t get it. For the most part, though, absent any kind of politicking (like, say, the arguments over the Hugo awards, in which people spend more time arguing about the authors’ identity politics than the work in question), if your work is good it will get more good reviews than bad ones. Don’t look at any single review. Your friends will tell you they like your book and they will review it accordingly… because they are your friends. Your enemies, if you have them, will hate your book and want you to die choking on crumpled pieces of the CreateSpace edition of it. Strangers, however, will occasionally read your work, and their honest opinions genuinely point to whether you accomplished your goal in writing the novel.

What you must NEVER do, when encountering a negative review, is obsess over it. There are quite a few immature authors out there, even authors who have enjoyed a reasonable amount of success, who flip the hell out over even a single negative review in a sea of overwhelming positives. They’ll leave nasty comments for the reviewer and may even go so far as to try and find them on social media. In fact, the reasonably successful authors are the worst offenders, because they have a social media audience of fans to whom they can turn to salve their fragile egos. If you, as an author making substantive money off your writing, feel compelled to screen-cap and share with your fans every individual bad review, you have a significant problem.

Your problem is that you can’t handle criticism. When you receive it, you need your fan club to cheer for you, hug you, and tell you that everything’s going to be okay. If you get angry at the reviewer, or go so far as to blog about what a son of a whore you think the reviewer is (by name, or by category, if you’re keen not to get sued), your writing will never truly improve because you can’t face your own shortcomings objectively. You’re too worried about lashing out at somebody who dared to tell you your work wasn’t already perfect.

Your writing must constantly evolve. If every book you write is not better than the last, if you’re not at the very least trending better in the aggregate, it’s probably also true that you have a high opinion of your work. Simultaneously, it probably enrages you when someone criticizes that work. Until you get past that, until you develop the maturity to look at negative reviews for what they are (and use them to improve your efforts), you’ll simply be some hack with an angry blog. The writing world has enough of those already.

You can do better than that. Learn to take and examine criticism. Until you do, you will not fulfill your potential. Until you do, you will not become a better writer.

March 31, 2016

Is This Deal Getting Worse All The Time?

A lot of working writers write without contracts. They write based on the strength of their client relationships. Provided there is never a problem, this is fine. Most of the time, when you meet a writer who prides himself on working without contracts, he’s also never had a client try to sue him, nor has he been stiffed for a significant amount of money. In the case of most disputes between a writer and his [disgruntled] clients, a contract could prevent the issue by defining the terms — such as, say, what remedies the parties agree to if the client isn’t happy with the output.

A lot of working writers write without contracts. They write based on the strength of their client relationships. Provided there is never a problem, this is fine. Most of the time, when you meet a writer who prides himself on working without contracts, he’s also never had a client try to sue him, nor has he been stiffed for a significant amount of money. In the case of most disputes between a writer and his [disgruntled] clients, a contract could prevent the issue by defining the terms — such as, say, what remedies the parties agree to if the client isn’t happy with the output.

I once worked with a writer who was… well, bad. Let’s call him “Steve,” which is not his name. Steve had written a massive 100,000 word fantasy novel of which he was very proud. It had been edited no less than eight times, he said. He had churned out x-hundred-thousand words of writing, and therefore he was a most excellent writer, he asserted. He paid up front for an editing job from me and turned me loose on his book.

Steve’s writing was bad. It was so bad that it prompted me to recalibrate my estimate of just how truly awful bad writing can be. I struggled through it and made significant changes to Steve’s book. He was happy with the output I sent him and all was well. But then I made a mistake: I sent him a list of helpful suggestions for how to improve his writing. While I wrote the list very gently and diplomatically, I think Steve was offended.

He wrote me back and demanded all of his money back because I didn’t completely rewrite his awful book. I explained to him that I was out my time and effort and, while I would make a good-faith effort to accommodate him (including taking another, free edit pass at the book, or taking more money to completely rewrite it), we could not start negotiations from the standpoint of, “Steve gets everything and Phil gets nothing.” I was willing to give him a partial refund if no resolution could be reached, but I was not willing to fork over every dime I’d been paid, especially since he would have the benefit of the edit work I had done.

Steve responded by threatening to tell the Internet I suck if I did not give him back at least half his money. I started ignoring him then.

A few days later, I got a letter from a lawyer’s office (emailed as a PDF). It said that Steve wanted his money and I should give it to him, or vague legal action might be considered. I had my lawyer call Steve’s lawyer and explain that Steve had engaged in extortion across state lines. Oddly, we never again heard so much as a peep from Steve or his attorneys, nor did Steve tell the Internet I suck anywhere that Giga Alert could see him do it.

A contract would have prevented all this right? Well, yes… and no. You see, just because you do have a contract (and I’m not saying you shouldn’t), don’t think that protects you in all things. Contracts are useful, but they’re not ironclad magical vestments that shield you from all harm. Contracts merely define certain specifics about your working relationship. There are always things that can come up outside the purview of the original agreement — and then you’ll be wondering what the hell to do about it.

I had a contract with a major publisher to produce several novels. That contract seemed like a guarantee of work I was to do and money I was to earn… except that it wasn’t. When the publisher was purchased by another publisher and the business was reorganized, my contract was killed. I was allowed to keep money that was prepaid to me, but I was not to turn in the work for which I was contracted, and I would not be paid for it if I did. The contract was superseded by a change to the business itself. I was not upset; this can and does happen. As a working writer, you’ve got to be aware of it. You can’t control all external factors, which means sometimes, you’ll think you have a guarantee of work, conditions, or payments… and then the rug will be pulled out from under you.

This happened to me just recently. I was performing contract work for a client who decided that, business-wide, all of his contractors would have to be classified as part-time employees — retroactively to the beginning of the year. I was told that I would have to submit to a background check and that my pay, including money already received, would become part-time employee pay (from which taxes were withdrawn) rather than 1099 contractor pay. I was sent a handy link to a background check service (one that, just a few years ago, was punished by the government for incorrectly reporting criminal background check results).

As much as I wanted to keep doing work under contract for this client, this attempt to change the terms of our deal after the fact — to alter the bargain, Darth Vader style — was unacceptable. As a freelancer I am not a part-time employee. I am a 1099 contractor and enjoy the freedoms this confers. I work on my own schedule, I do not submit to background or credit checks, and I answer only to those people with whom my contract is drawn up. There was no way I would be bullied into agreeing to change our contract. I entered into a business agreement with this client under a specific set of assumptions. If those premises change, the deal is off and the work stops.

When people start using the term “retroactively” with respect to a contract you’ve signed, your agreement has become untenable. The only answer to such a demand is a firm, “No.” Never let anyone bully you into changing an agreement… and never believe the fact that you have a contract will stop some clients from trying.

The price for being a working writer is eternal vigilance, which includes a commitment to ongoing business development. Every client is temporary. Some go their own way quietly, while others cut their own throats by trying to change your working agreement. Either way, you must always be looking to replace the business you’ll lose.

February 12, 2016

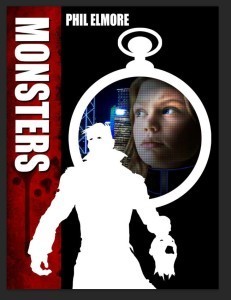

Monsters: The Complete 4104 Serial Novel

My novel, Monsters, is finally available in both Kindle and paperback formats. The book was completed in 2014, but the usual delays and scheduling conflicts meant that it hasn’t been on the shelves until now. I’m extremely proud of Monsters and believe it to be some of my best work to date. I hope you will agree. Get yours today on Amazon.

My novel, Monsters, is finally available in both Kindle and paperback formats. The book was completed in 2014, but the usual delays and scheduling conflicts meant that it hasn’t been on the shelves until now. I’m extremely proud of Monsters and believe it to be some of my best work to date. I hope you will agree. Get yours today on Amazon.