Phil Elmore's Blog, page 11

January 9, 2015

DETECTIVE MOXLEY, Part 2: “Everybody’s Sorry”

Moxley sat in a robot diner on Wernerplasse, rolling a flavored vapor tube from one corner of his mouth to the other. Before him on the table lay a pocket tab. He was using it to scroll through surveillance feeds.

Moxley sat in a robot diner on Wernerplasse, rolling a flavored vapor tube from one corner of his mouth to the other. Before him on the table lay a pocket tab. He was using it to scroll through surveillance feeds.

It made no sense. He simply could not wrap his brain around it. Ray Neiring was boring’s next door neighbor. The man was the definition of “by the book,” never straying any farther from the rules than Moxley could tempt him. So why was Mox now scanning through half a dozen recordings that showed Ray Neiring breaking the law?

His phone vibrated against his thigh. It had been doing that all morning. The on-off vibration pattern was for contacts he had blacklisted. Bill collectors and lawyers, for the most part. He knew a moment’s anxiety as he considered that Rena Terry’s attorneys had finally tracked down his new number.

Moxley sighed and swallowed the last of his bulb of coffee. It was burned and tasted of plastic. He drank it anyway and continued ignoring his phone. His eyes were locked on the tab.

In one low-res crawl, Neiring was shown breaking into the home of his supervisor, a government inspector named Jeffrey Teller. Apparently Neiring had ransacked Teller’s residence and then fled. He was shown in a series of still shots from a remote camera in a robot bodega a few blocks from Teller’s house. It was Neiring, all right, and he was using a prybar to pop open a sucrose-water dispenser. The stills showed him filling his pockets and then leaving without even trying the chit module built into the machine.

Who would knock over a convenience store for sugar water and ignore cash?

Another feed, predictably, showed Neiring smashing a slidewalk protein bar vendor. The recording was from the vendor’s own built-in camera, so the recording was at a crazy angle. There was no doubt that it was Ray, though. Moxley couldn’t figure the dead-eyed expression on his friend’s face. Neiring ripped open the vendor’s housing and took a stack of protein bars, but he never changed expression. He might have been standing in a pay toilet for all the interest he showed in what he was doing.

“What were you after, Ray?” Moxley said quietly. “What were you into?”

Moxley’s first thought had been drugs. A hidden addiction that ramped up quickly and unpredictably would explain Neiring’s bizarre behavior, but drugs weren’t Ray Neiring. Ray looked askance at Moxley’s incipient alcoholism; there was no way he was nursing a Sleep habit. Was it something else, then? Maybe custom pharmaceuticals? Designer drugs could produce a strange mixture of symptoms, and that would fit, but Mox didn’t like how that smelled. It was an easy answer, but it was wrong. His gut refused the easy out.

Moxley tucked the tab inside his coat, swallowed the last of his burnt coffee, and began making a list in his head. He had three more records that also showed Neiring committing crimes. But there were no public tickets in the system on Ray, no alerts or lookouts. That, too, made no sense… and he could think of only one explanation.

Moxley’s phone trembled in his pocket. He fished it out and put it on the table. A tiny holographic carat appeared in the air above it. Mox thumbed the face of the phone to chase the icon away. That was just the alarm system built into his office. His security system had just discharged another tray of nails at a would-be intruder. He was going to catch hell from his landlady about that. He thumbed the phone again.

“Memo,” he said. “Plaster dip.” The phone trembled when he tapped it. He dumped it back in his pocket, stood, and threw a plastic chit on the tabletop before leaving the diner.

He had too much time to think about Ray as he drove across town. The car belched smoke from both bow and stern. Its AI was permanently brain damaged. Moxley didn’t need the navigation system, though; he knew Hongkongtown like a pedicab driver.

Traffic was the usual riot of hydrogen bikes, runabouts, and pedal carts, liberally mixed with pedestrians who clearly believed their lives were charmed. The average Hongkongtown foot commuter simply ignored anything on more than two wheels. Street etiquette said it was the bigger guy’s job to avoid anything smaller than he was. There was something vaguely maritime about it.

“Larboard on Dragon face,” whispered the car from a taped-over speaker in the dash. “Mandy pumpkins meters pancakes with a safe and legal u-turn.” Mox had tried dumping an entire mango shake down there once. He had long ago disconnected all of the drive circuits, so at least the damned thing couldn’t lock the brakes or send him careening into a building. He also kept pasting layers of tape to the speaker to muffle the car’s mindless ravings. The AI, stubbornly, refused to stop talking.

“Shaddap,” said Moxley, not without affection.

“Shaddap,” said the car in his voice. “Gimme three soy dogs to go.” That was yesterday’s lunch order. The car’s audio pickups would occasionally isolate voices inside and outside the vehicle, record them, and play them back. Last week, the car had scared the daylights out of him by playing back a snatch of street noise replete with a hooker shouting bloody murder at her pimp. Unfortunately, he couldn’t simply find the AI and yank it. The old car’s ignition and electrical system was wired through the Automotive Intelligence, so jerking the thing out of there would leave the vehicle dead. Replacing it was also out of the question. This was a Monkton Dayliner, a model that was twenty years obsolete. Replacement parts cost a fortune and a salvaged AI module was several tropical vacations out of his price range.

He cut through the outer ring of the Redlight, trying to avoid the worst of the morning commute volumes. On Vega Ave, a Human Services van was parked in front of Madame Oy’s. Moxley wondered if they were raiding the joint or simply patronizing it. He made a mental note to avoid the place either way.

It was mid-morning by the time he pulled into a reserved spot in front of Building 801. This was one of several bureaucratic waystations ringing Hongkongtown. It was also where Raymond Neiring had worked and, he realized, where Ray’s official-use vehicle might still be parked. Maybe he could find it and poke through it. There had to be a way. That was not why he had come, however. He was looking for—

“Violation,” said the parking robot that rolled up to the crumpled gold nose of his Dayliner. “This is a non-parking area. Violation. Violation.”

“Six one,” said Moxley. “Five one. Four Three. Override beta beta sixkiller.”

The robot buzzed and shuddered as if offended. Finally, it withdrew, rolling noisily away on the slidewalk. Moxley grinned and spat out his spent vapor tube. He ambled up the stairs, entered the building, and managed a reasonable approximation of haste as he made his way to a cubicle at the rear of the building’s desk farm.

Every person in this building was a government inspector. That meant any one of them could arrest Moxley if they saw a reason to do it. Moxley waited for the man seated in front of him to turn around, to acknowledge his presence. He quickly grew impatient.

“Hey,” he said.

“I’m busy,” said the inspector.

“Fine,” said Moxley. “Then you’re under arrest.”

The inspector stopped pawing at his touch screen. Mox watched his shoulders tense. The inspector was wearing a pistol on his right side, under his shirt. It would be something small, probably a government-issue compact loading explosive rounds. Deadly enough from across a room. Certain death at the width of a cubicle.

“What,” said the inspector, slowly turning in his chair, “do you want, Moxley?” The ID badge he wore identified him as Aldo Shebeiskowski. The holographic image of Shebeiskowski’s face was several years too young.

“Hello, Sheb,” said Moxley. “Nice to see you, too. So sorry to hear about your best friend losing his clowns and running amok in the streets. How can I help you?”

Shebieskowski glared at him, then sighed. “All right,” he said. “All right. Point taken. I really was sorry to hear about Ray, Mox. What do you need?”

“How easy is it to delete something from the city network?” asked Mox.

The inspector blinked. “How… what? Why do you want to know that?”

“I have this problem,” said Moxley. “My best friend is lying scattered to ashes on the floor of a storage locker.”

“You don’t have any friends,” said Shebieskowski. “And I told you I was sorry about Ray.”

“Yeah, you did,” said Mox. “You’re sorry. I’m sorry. Everybody’s sorry. But that’s not going to scoop him up and pour him back into his pants, is it? Ray was on a rampage in the last week of his life, Sheb.”

“Yeah? So?”

“So,” said Mox, “I want to know why you helped cover it up.”

January 7, 2015

Technocracy: Islam Is Incompatible with Modern Technology

My WND Technocracy column this week was inspired by the latest Muslim act of terrorism and mass-murder, this time at the offices of the Charlie Hebdo paper in Paris.

Islam is incompatible with modern technology because Islam is incompatible with the Western world.

Islam is utterly incompatible with the modern, Western world. The two will never be able to coexist peacefully, because Islamists will not permit this.

Read the full column here in WND News.

January 1, 2015

DETECTIVE MOXLEY, Part 1: “He Died Hard”

“Well,” said Moxley, “he died hard. No argument there.”

“Well,” said Moxley, “he died hard. No argument there.”

Siengold narrow-eyed the detective for all he was worth. Siengold was a Goop; he was supposed to hate private detectives. Like so many of the government operatives, however, he took real pleasure in this particular unspoken tenet of his job. Around the two men, a pair of forensics drones hovered on fitful turbofans, their imagers strobing away as they indexed the crime scene. A pair of Siengold’s subordinates milled in the hall outside the storage unit, working hard to win a glaring contest. The subject of their competition was Harold Moxley and they wanted very much for the detective to know it. Moxley pretended he did not notice, more from spite than from diplomacy.

Moxley squatted with some difficulty, holding the hem of his overcoat so it would not drag through the pool of blood. The crimson puddle was congealing. There were portions of the polished floor to which the blood had been burned, almost cooked, which was consistent with the incinerator pistol lying on the floor. Most of the man’s body had been blown to atoms by the blast. The contents of his pockets — protein bars, empty wrappers, and burst pouches of sucrose-water, had been scattered around the storage locker by the explosion.

Some of the scraps of fabric had once been slacks. Moxley identified a pair of belt loops, although nothing that looked like a belt. The largest part of the dead man’s body still intact had once been his face. Moxley realized he was staring at the back of the man’s eye holes. The heat wave of the incinerator had lifted the face off like a mask and dumped it on the floor. He had seen that once before.

“This mess,” said Siengold, following Moxley’s gaze, “is why only a moron kills himself with an incinerator.” He seemed to think he was being clever.

“Lieutenant,” said one of the men in the hallway. “His time’s up.”

“Let’s go, Mox,” said Siengold. “You’ve had your twenty minutes.”

“I’ve got a contract,” said Moxley. “You and your bully boys can just wait for me. Unless you’d like to explain a breach to the Labor Board? No? Then back off and let me do my job. Maybe learn something.”

Siengold glowered at him. One of the Goops in the hall sniggered. Moxley was used to that. He knew how he must seem to them — old, broken, fifty pounds overweight, his moon-shaped face pocked and scarred. He was hairy every where a man should not be, bald everywhere it counted, and he hadn’t shaved in three days. His overcoat was stained and his hat was lived in. He was a squat, broadly built man, stronger than he looked, with gnarled hands and tired eyes.

And he was still a better Detective than any five of these goons.

Keep telling yourself that, he thought. Maybe it’s true.

“Did the drones type and print the gun?” asked Moxley. “Who found the body?”

“No prints,” said Siengold. “The doors on these units aren’t hermetically sealed. There’s enough clearance that blood from what’s left of the body seeped out into the corridor. The manager comes in once a week to do billing in the front office. He saw the puddle and called it in.”

Mox looked up from where he was kneeling. “No prints,” he repeated. “On the gun this man used to incinerate himself. Which he then dropped because there wasn’t enough left of him to hold it.”

“Yeah,” said Siengold. “We figure the heat of the blast did it. There’s no DNA, no skin oil, nothing on the pistol. I checked with Central’s armorer. He said there’s precedent.”

Mox didn’t like it. He looked back to the two Goops eye-balling him from the hallway and his gaze followed the perimeter of the storage room door. “Magnatic locks?” he said.

“Sealed from the inside,” said Siengold. “The whole system’s controlled by a pocket AI in the front office. Nobody’s opened the door since this poor bastard locked himself inside. He was in here for a while, judging from the water and the protein bars. Might have been a squatter.”

“A man so poor he’s living in somebody else’s storage locker,” said Moxley, “who just happens to have an illegal pistol worth five hundred in hard plastic, easy.” He shook his head. “What’s in these boxes?” He gestured to the few pasteboard crates haphazardly strewn about the storage locker.

“Machine parts,” said Siengold. “That’s all they store here. It’s some kind of archive for an R and D microfactory at the edge of the Redlight.”

“You check the other units?” Moxley braced his hands against his thighs and pushed himself to his feet.

“That a trick question, Moxley?” Siengold said. “Bylaws say we can check the adjacent units, so we did. Nothing.”

“Just checking,” said Moxley. “My client is the holding company that owns this joint. Well. Their insurance company.”

“Sounds very civic-minded,” said Siengold. “If you ask me, dissolving the freecops was the smartest thing the city council ever did. Pay to play may be what Hongkongtown was built on, Moxley, but it makes for piss-poor justice. Police for the folks who pay and not for the others? That isn’t equal rights.”

“You strike me as a paragon of equity,” said Moxley. “Fortunately, the law that changed freelance policing has nothing to say about commercially employed private detectives.”

“Not yet,” said Siengold. “Give it time.”

Moxley swallowed one of his better insults. His eyes went to the walls, just below the ceiling. The only opening was a circular grate no wider around than his wrist.

“This goes next door?” Moxley asked.

“I told you, we checked the adjacent unit,” said Siengold. “You think he was murdered by a cloud of smoke? Not even a Squeeze could fit through there, Moxley.”

“I wouldn’t know,” said Mox. “I’ve never seen one.”

“They picked up two of them just last month,” said Siengold. “Hiding in a laundry off Shenzhen Boulevard. Human Services has been working with our joint government task force. There are a lot more Ogs in Honkongtown than anybody thought.”

“So I keep hearing,” said Moxley. “Maybe you should be focusing on Sleepers instead of Augments. There were three more wildings this week, Siengold. What are the Goops doing it about it?

“Don’t use that word with me,” said Siengold. His voice was sharp. Mox had to remind himself that this man had real power, no matter what the detective thought of Siengold’s character.

“Street slang,” said Moxley, turning back to the body. “I spend a lot of time dipped in it.”

“That’s what I hear,” said Siengold. “Been through the Redlight recently, Moxley? Funny thing. Flowers says you owe them like five large. Had a look at your credit history lately?

Moxley waved a middle finger at him. “I was out with your mother. She has expensive tastes.”

“Eat it,” said Siengold. “Finish up and get out of my sight. I want to seal this scene and get back to the office.”

“In a minute,” said Moxley. He fished the scratched disc of his phone from his pocket, licked the back, and pressed it into his palm. He ignored the face Siengold made. The beleaguered phone adhered, finally, and Moxley held his palm up to take a photo. Using the metal stylus he carried in his shirt pocket, he reached out to flip the scrap of face over.

The Goops had a DNA database and couldn’t care less about facial recognition, but Mox’s own database was a bit more antiquated. His image processing equipment might be able to pull up an identity and might not. It was worth a shot. If he failed, he would have to pry the information out of Siengold or, more likely, bribe a middle-man to pay the Goop for the information.

The blood-soaked skin unfolded. Its lips were flat and blue. Even without a skull behind it, the features were unmistakable.

“Oh my God,” said Moxley.

The face belonged to Raymond Neiring, his only friend.

Technocracy: Working stiffs carry load for shiftless Obama-bots

Those of us who do work, who carry Obama’s constituents on our backs, are therefore Democrats’ slaves…

I work very hard to make a living. My WND Technocracy column this week is about all the people being kept alive by the third of my paycheck that is stolen from me every week… and the thousands of dollars in income tax that I pay every year to a government that doesn’t care how it wastes my sweat and blood.

Read the full column here in WND News.

December 25, 2014

Technocracy: Beware Feminists’ New Man-Stabbing Dress (Now with More Feminist Outrage!)

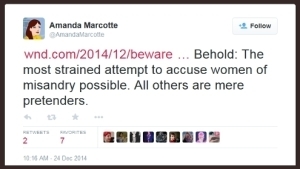

No less vile a human being than arch-feminist Amanda Marcotte took notice of my WND Technocracy column this week, which uses as its jumping-off point a bizarre piece of 3D-printed couture that attacks anyone who approaches it too closely.

No less vile a human being than arch-feminist Amanda Marcotte took notice of my WND Technocracy column this week, which uses as its jumping-off point a bizarre piece of 3D-printed couture that attacks anyone who approaches it too closely.

The dress itself is absurd, of course; I used it merely as a physical manifestation of the trend among progressive women these days to be completely incapable of coping with even the slightest social adversity. This lack of social skills has led social-justice activists to redefine as affront all benign masculine behavior, mostly because feminists and neutered male libs all hate actual men.

One day, I’ve no doubt that some variation of this contraption will be used to shield these wilting feminist flowers from any and all unwanted social interaction, sight, or sound. Until then, we have the bleating of social-justice wieners like Marcotte, who see evil conservatives lurking under every rock and behind every tree.

Marcotte posted a link to my column and then immediately blocked me when I took notice. It’s hard not to notice the irony there — a self-described loud-and-proud grrrl-powered feminist who can’t even handle an exchange of 140-character comments.

Read the full column here in WND News.

December 18, 2014

Technocracy: Ban steak knives at airports?

Politically correct hysteria over one of humanity’s most ancient tools is the reason “zero tolerance” policies punish good students who bring to school items as harmless as butter knives.

My WND Technocracy column this week is about anti-knife hysteria.

Specifically, people are now calling to ban round-tip steak knives at airports, as if such a knife could be used to hijack an airplane.

Somewhere in the course of writing this column it became a rant about the TSA’s employees. You can read the full column here in WND News.

December 15, 2014

“Carol of the Bells,” a Christmas Short Story

When the dog spoke to him, Gavin knew his father had been telling the truth.

When the dog spoke to him, Gavin knew his father had been telling the truth.

He was loading the last of the groceries in the Aerostar, making sure to hang on to Henry’s biscuits, when the Jack Russell Terrier hopped into the cargo area of the minivan.

“I’ve got them, boy, I’ve got them,” Gavin promised. “Just let me get in the van.”

“It’s time, Gavin,” said Henry. He was wagging his tail furiously.

Gavin froze. He could feel the blood draining from his face, could feel the sudden knot in his stomach. He looked at the little dog as if he had never seen the animal before.

“Henry?” said Gavin. He looked left, then right. There was nobody nearby. The parking area was busy, but he was alone in this icy corner at the back of the lot. The speakers outside Furnham’s were playing “Jingle Bell Rock” for the fourth time in the last two hours.

“It’s today,” said Henry. Then he barked, once, and returned to his blanket on the passenger seat.

Gavin drove his groceries home in a daze. Twenty-two years, his father had said. Sometimes thirty-three. Once, forty-four. But never less than twenty-two. And maybe never.

Maybe never. He had clung to that hope over the years. With each passing Christmas, he had tried to convince himself that Dad was sick. It was the “chemo-brain” talking. That’s what the doctors had called it. It was a fever dream, a fantasy.

His father’s last words had been, “I love you.” He hadn’t woken up again after that. But he’d said something just before, something that had confused and puzzled Gavin through the years.

A cat is enough, Gavin’s father had said. But cats aren’t loyal. Get a dog. The animals will tell you.

He looked down at his watch. Clarissa’s recital was at seven at the school. Did he have enough time to get to the storage locker? No; it was too far out of the way. He and Judy would have to drive separately.

Henry said nothing else. Gavin kept looking at the dog, expecting something more, but as far as he could tell, it was the same dog he’d brought home to the girls four years ago. Henry was only the latest ambassador in a long line of family dogs. At forty-three, Gavin could not count how many he had owned.

Cats aren’t loyal. Get a dog.

He pulled into the garage next to Judy’s Honda, barely waiting long enough for the opener. He put Henry in the kennel. When he let himself in through the kitchen, Cinnamon was lying on the throw rug in front of the refrigerator. Gavin put down his groceries and eyed the cat, waiting.

Cinnamon yawned.

Had he imagined it? Once, maybe. Once could have been wishful thinking. But Henry had spoken twice. Gavin had heard him. It was real. He believed it was real.

“Today,” Cinnamon finally said. Then, as if delivering this message were beneath its dignity, the cat stood, stretched, and strutted from the room.

Gavin leaned against the countertop. His heart hammered in his chest. He looked at his watch. He could hear the girls playing in the next room. The implications hit him. Clarissa was eight. Dawn was fourteen. He did the math in his head.

Maybe never.

“Gavin?” asked Judith. She was holding the box of ornaments they kept in the attic. This she placed on the counter next to the groceries. “Are you all right? You’re not getting sick, are you?”

“You have to drive the girls,” he said.

“Gavin, you promised,” she chided. “Don’t make me sit through this by myself.”

“I’m going,” he said. “We’re all going. Tell Dawn to get dressed.”

“But you said she could stay home. You know how bored she gets at these things.”

“We’re all going,” said Gavin again. “But I… I have to go to the locker. I need it.”

Judy looked at him like he’d lost his mind. “Need what? What are you talking about?”

“I have to get Steve,” said Gavin.

Now it was Judith’s turn to go pale. She put one hand to her chest, clutching her sweater. It had reindeers stitched on it. “No,” she said. “Not tonight. Gavin, not after all these years.”

“Yes,” said Gavin. “After all these years. Thirty-three of them.”

Judith’s eyes went wide. “Your father…”

“Yes,” said Gavin. “Christmas Eve. Christmas Eve, just like he said. Thirty-three years later.”

“Can’t we, I don’t know, just stay home?” said Judith. “I’ll cancel. I’ll say she’s sick. We can lock the doors, just stay in.”

“And then what?” said Gavin. “Let it happen here? It’s going to. Just like Dad said. The school is at the edge of town. There’s the athletic field. It’s big. There won’t be any lights. I’ll do it there and then meet you at the recital.”

He turned to go.

“Gavin,” said Judy. She grabbed him, holding him close, and he put his arms around her.

“Dad did it,” he told her. “So did Papa Erway. If they could do it, so can I. Dad said it was in our blood.”

Her eyes were hopeless. He wanted her to say something, wanted her to wish him luck or tell him to be careful. She shook her head. He nodded, once, and left.

The roads were wet but passable. Snow was falling. It was a beautiful winter night with a full moon. The moon needed a movie Santa, flying past in silhouette.

The locker was covered in dust. The storage fee was automatically billed to his credit card. He rarely thought about it.

His hands shook. He dropped the key in the snow, dug it free, and finally got it into the lock. Cobwebs brushed him when he lifted the shutter door.

Every locker had a motion-detector light. It was bright and uncomfortable. There was nothing in the locker — nothing except Steve, wrapped in a wool Army blanket. Gavin unwrapped the bundle, spread the blanket on the floor, and examined his prize.

The Dread Weapon Steve was a gaudy thing. The double-edged sword was as tall as Gavin, with a massive skull-shaped hump where its cross-guards were mounted. The pommel, too, was a skull, although smaller. Runes covered the blade.

A weapon like this should have a name, his father had said to him. Gavin, then fourteen years old, had laughed. Name a sword? He thought it was silly. He had suggested “Steve.”

Steve it is, his father had agreed. The Dread Weapon Steve. Six generations and no one in our family has thought of that. I’m proud of you, Gavin.

He had felt shame, then. Shame at his father’s pride. Shame that his father took him seriously when he himself did not. Shame that his father believed in silly family legends.

“I’m sorry, Dad,” he said quietly.

The Dread Weapon Steve was much lighter than it looked. He hefted it easily. When he was fifteen, his father had given him a wooden replica, carved to exact detail. That had been much heavier and Dad had insisted he learn to wield it. Now, swinging Steve through the air, he found it comfortable. As the blade moved, it hummed.

Gavin drove to the school. He stopped short of the property, parking the Aerostar on the street next to the bus circle. Taking Steve from the back, wishing he had brought his hunting boots, he stepped out into the snow.

A stand of pine trees bordered the athletic field. He marched through the snow to this, where he could wait unnoticed. Far across the field, beyond the access road to the runners’ track, the lights were on at the school. He looked to his watch. Quarter to seven.

He leaned against one of the pines. The air was cold but not painful. The untouched snow, marred only by his own tracks, glittered in the moonlight. A gust of wind drove frigid dust under his nostrils. He coughed.

“He’s waiting,” whispered a voice.

Gavin looked up. A squirrel, perched on the lowest branch, stared down at him. “Where?” he asked it.

“In the field,” said the squirrel. It did not blink. Its black eyes held nothing; it was taking no sides. “Go to the middle of the field and he will come.”

Gavin nodded. Holding the Dread Weapon Steve low by his waist, he walked out into the snow. The gusts were picking up now. Every step he took signaled the wind to blow harder. Finally, the snow before him was swirling in little eddies, forming tiny funnel clouds of ice crystals.

His father had described that, too.

When at last he stood in the center of the field, Gavin held the sword aloft. The snow before him erupted, becoming a mound. The mound became a hill. The hill became a giant. When the snow giant grew fingers, grew a face, grew a mouth, it opened eyes that glowed. Gavin had never seen so blue a blue. He had never felt so cold a cold. Near the thing, near the monster, the temperature dropped. Sudden frost painted wandering patterns in the snow.

“Erway,” said the monster. Its voice echoed, a bass rumble that Gavin felt in his chest. “He would be an old man now. As you will be when I return.”

“I am Erway,” said Gavin, remembering the words. “My father was Erway. His father was Erway.”

“So you are,” said the monster. “The curse has lain long on your family. And so it is that you face me now.”

“So it is,” repeated Gavin. “Release me. Release my family.”

“Not this Christmas,” said the monster. “Not Christmas years hence. Perhaps never.”

The creature lunged.

Gavin Erway brought up the sword that his father had taught him to use, and the two fought for half an hour.

I know, because he told me.

He was late to my sister’s recital.

That night, when he tucked us into bed on Christmas Eve, he told me the story. Told me how Samael Erway, a sailor on a merchant ship, had once cheated a Romany man during a card game. Told me that the curse placed on our family that Christmas had stayed with Samael’s descendants for six generations.

When I unwrapped the wooden sword Christmas morning, my mother gasped. I caught her crying at brunch. I didn’t understand, then, the look that my parents shared. Resignation. Concern. And pride. In my father’s eyes, there was pride.

He passed a few months ago, far too young. Before he went, he warned me. Told me he was proud of me. Told me he loved me. When he died, he was smiling.

My name is Dawn Erway. My father was Gavin Erway. His father was the man we called Papa Erway. I am thirty-six years old.

It is Christmas Eve, and my dog just told me to get my sword.

December 11, 2014

Episode 50, “Across the Gulf Bridge”

The little girl hums softly to herself. She is guiding a powered wheelchair, custom-built, through the busy streets of Hongkongtown. It is a bright, sunny day, with low ozone and a cool breeze coming off the ocean. People are everywhere, coming and going, in cars and pedicaps and hydrogen bikes and ground cars. The city is alive and so is her father.

The little girl hums softly to herself. She is guiding a powered wheelchair, custom-built, through the busy streets of Hongkongtown. It is a bright, sunny day, with low ozone and a cool breeze coming off the ocean. People are everywhere, coming and going, in cars and pedicaps and hydrogen bikes and ground cars. The city is alive and so is her father.

He is healing, albeit slowly, given the extensive damage done to him. Sight is returning to his bandaged eye. He offers her a gap-toothed smile when she pauses to check on him; she smiles back, proud and happy. She is happy because, for him, the pain and sorrow are over. For once in his life, her father will enjoy the rest, the reward, that he has earned through his blood.

They travel slowly, for there is no rush. Unseen by them both, an army of machine-people is watching: Ogs, disguised as common robots, chart their progress, ready to intervene should any danger befall their champions. They do not know what the little girl knows: Already, her father’s criminal records have been purged forever from every computer network. Any record of her, or him, or the events surrounding the last months, has been permanently deleted. Only in the whispers of the street people of Hongkongtown will their stories be remembered.

The little girl, and those she now calls her sisters, have much work ahead of them. Already, several of their number have gone to different cities throughout the world, positioning themselves for the decades-long strategy they will follow. As they maneuver themselves, they also maneuver in the virtual world. They establish a number of financial accounts, filling them through legal and extralegal means, arranging for the resources they know they will need.

One such account now belongs to the little girl’s father, coded to his hand print. It contains more money than he will ever possibly need. Also coded to him is property: He now owns a peaceful island, and a rather extraordinary drinking establishment, in the Keys. There, in the sun, surrounded by pretty girls and a helpful staff that most will believe to be robots, he will convalesce. There, he will live out his natural life, however long that may be. Given his ability to regenerate, it may be forever. He has no way of knowing. The little girl promises to visit him.

He asks her once more if she will not change her mind. Could she come to the island with him? But no, this is not her destiny. He knows it; she believes it. He asks because he must ask, because no father could resist. But he also knows that she bears a powerful gift, a remarkable destiny. He tells himself that he will watch the news. That he will look for clues, for signs. That he will smile every time he sees what he thinks is evidence of his little girl and her sisters ruling the world.

She has made a gift to him of the gold pocket watch she carries. Inside the watch, she has placed, very carefully, her own picture. He is too big for wristwatches, she has told him; a pocket watch is appropriate for him. It was for this reason that she chose it. It seems like so long ago that they entered the watch shop together. Think of me whenever you look at the watch, she has told him. It will make me happy, knowing you have something of mine with you all the time.

He does not know it, but a surprise waits for him on the train that will carry him across the Gulf Bridge and to the Keys. This surprise is his friend, Montauk, an Augment. Montauk has undergone extensive repairs to both mechanical and biological systems. Montauk will enjoy relaxing in the peace and quiet as much as the little girl’s father. Montauk, too, needs time to heal, for the Og’s loss is great. Their mutual friend Loran was Montauk’s son, Samuel, only recently become an Og. It is Montauk’s belief that its son died fighting for Augment rights. This dream of equality, this dream of the future, is one that Montauk shares with the little girl. One day, the people of Northam will let go of class distinctions, will release their insistence on human percentages. Montauk believes the little girl and her sisters can make this dream a reality. From this belief, Montauk draws comfort. In this belief, Montauk may one day find satisfaction. This will take time. Montauk will live out its days feeling the loss of Samuel, of Loran.

Knowing it will help both Og and man, the little girl relishes the thought of her father’s reunion with Montauk. She will miss them both. She has a great deal of work to do, however, and if her father remains, they will remain each other’s point of vulnerability. Hard choices and difficult politics await the little girl. She cannot have enemies — enemies she has not yet even made — using her father against her or threatening him with her harm. She loves her father. Like all children who love their parents, she wants him to be safe, to live in peace, and to be happy.

She is not sure why she is crying. Her father, too, is crying, but she knows why: He loves her with all his heart, and he will miss her. He will be thinking about her, he says, until she comes to visit him. And he hopes she will come soon and often. She promises him that she will do what she can.

As the wheelchair hums along, she passes a news kiosk. There are ozone warnings. There is talk of the ’36 Olympics. There is continuing coverage of what is now called The Hospital Bombing. There is news of a series of recent traffic accidents, officially unexplained. A government employee named Stevens has been killed in a freak accident involving a malfunctioning garbage robot. It has been two weeks since a warehouse in the Redlight burned down mysteriously. In that time, several persons on the public sex offender registry have been found dead, all of them victims of apparent in-home accidents.

Hongkongtown’s child molesters, the little girl suspects, will continue to die mysteriously for years to come.

As they walk to the train station, they pass a block of flats near the freightyards. Children play here. These are the children of the dock workers, playing in the mid-morning sun. There are boys and girls. Many of them skip pairs of rope. The little girl likes seeing them skip rope, likes hearing the rhymes they speak as they weave in and out of the double strands:

Everyone says it can follow you anywhere.

Everyone says that it never gets tired.

Everyone says it won’t go in small spaces.

Everyone says it needs darkness to hide.

Everyone says that it crushes your skull.

Everyone says that it follows The List.

Everyone says it may wait in your home.

Everyone says that you’ll never be missed.

Everyone says it’s already too late for you.

Everyone says that it puts out your eyes.

Everyone says there is no hiding place for you.

Everyone picked by the little girl dies.

The little girl’s father will become a Hongkongtown street legend. For years, the dregs of Hongkongtown’s criminals, the worst men and women in the worst neighborhoods of the city, the Sleepers and the creepers and the thieves and the rapists, will tell a story amongst themselves. They will speak in hushed tones of the monster, the creature that stalks the streets of their city, the creature that knows neither pity nor mercy…

…and her father.

December 10, 2014

Technocracy — ‘Metaverse’ Porn: Danger Ahead

My WND Technocracy column this week is about the increasing likelihood that technology will facilitate us “checking out” of reality.

The allure of creating a fantasy world in which virtual reality conforms to our whims is simply too great.

Virtual reality environments are becoming better and better. When we invent a “holodeck” equivalent, society will shut down because nobody will ever leave the house.

Read the full column here in WND News.

December 4, 2014

Episode 49, “The Best Father”

Peyton spat one of his own teeth onto the tiled floor. He reached up with one aching hand and probed the wound in his cheek. The hole in his face would close. The tooth would grow back, although very slowly. He had learned that lesson in prison.

Peyton spat one of his own teeth onto the tiled floor. He reached up with one aching hand and probed the wound in his cheek. The hole in his face would close. The tooth would grow back, although very slowly. He had learned that lesson in prison.

He tried to get up. He couldn’t. He simply didn’t have anything more to give. VanClef came to stand over him.

“You poor, deluded bag of meat,” said VenClef. He held his pistol loosely in his hand, as if he had forgotten it. “Did you really believe you could do it? Fight your way past everything I could throw at you, kill me, take your daughter back? I think you did. I don’t remember you being so deluded, Peyton. But then, it has been a long time.”

“I don’t know you,” said Peyton from the floor. His arms were so heavy. So very heavy.

“No,” said VanClef. “I forget that I observed you from behind one-way glass. Believe me, Peyton, I regret not simply ending your life, or placing you immediately in cold storage, once you delivered your sample. But your prison sentence made that quite impossible. As much power as Intelligence has, its power is nothing compared to the almighty bureaucracy. It was easier to let you rot in that place, even after you put yourself on death row. Why couldn’t you have just done us all a favor and gone through with it?”

“My daughter,” said Peyton. “She wasn’t supposed to exist. I wouldn’t know. But there was an error.”

“You… you still haven’t figured it out, have you?” VanClef said. “I had to make quite a show of my ignorance for the others on my staff. If any of them had suspected just how brilliant your daughter and her cousins are, there might have been a panic. Even your daughter thinks I’m a moron. I’ve known all along just how brilliant the children are. If I didn’t, I would hardly be fit to run Project Violet.”

“Figured it out…?” Peyton asked. His voice was a whisper.

“The computer ‘error,’ Peyton,” said VanClef. “She programmed it. She made it happen. She and the others were digging around our computer system for weeks before we discovered them and tried to shut them out. By then it was too late. Some of them escaped. The others locked themselves in and reprogrammed the defenses. It was all we could do to keep them contained while I kept my staff believing it was a series of malfunctions.”

“She’s… smarter than you,” said Peyton.

“Of course she’s smarter than me,” said VanClef. “She’s smarter than everyone, you fool. I had hoped that through brain analysis, we could learn how their minds work. Selective breeding and the cultivation of a perfect genetic sample through endocrine rebalance will only take us so far. I have to unlock the mystery of why their minds operate as they do. For that I need at least one subject. Your daughter will do for a start. If I can show Intelligence real results, they will reinstate Violet and I can stop looking over my shoulder.”

“Annika… Annika… wanted me… to find her.”

“You don’t look well, Peyton,” said VanClef. “But yes. That’s what I said. Peyton, you don’t realize this, but she’s been using you from the start. You think targeting child molesters was your idea? You think any of the steps you’ve taken to this point were done on your initiative? Think about that, Peyton. Try very hard. When have you ever in your life shown initiative? You’re a concrete thinker, Peyton. You aren’t creative. You don’t imagine. It’s why you turned to violence as a profession, and why you ended up in prison in the first place.”

“No–”

“Yes,” said VanClef. “At every turn, she told you what you needed to hear, led you in the directions she needed you to go, in order to accomplish her aims. You completed the plan to free the girls from my ‘school.’ You targeted a class of criminals that she and her counterparts find particularly upsetting — and specifically a threat to them. You think you’re protecting her? You’ve been taking your cues from her for weeks. That’s what she does, Peyton. That’s how she’s designed. Hers is the kind of mind that will run this world one day. She’s the future.”

“She’s my… daughter,” said Peyton.

“She doesn’t need you anymore, Peyton,” said VanClef. “You’re nothing but muscle. Or you were. Now what are you? Just so much broken meat.”

Peyton managed to look up at VanClef with his good eye. What he saw made him smile. He started to laugh. Each time he laughed it made his ribs grind together. The pain was extraordinary.

“Good-bye, Peyton,” said VanClef. He extended his pistol. “I may have to shoot you in the head a few times to kill you. But I think we’ll figure it out eventually.” When Peyton continued to laugh, VanClef scowled. “What? What is it?”

“She’s a genius,” said Peyton.

“Yes? And?”

“A genius… who knows how… to use a watch fob… to pick a handcuff lock,” he gasped.

Annika, holding the military Og’s broken combat knife, slashed VanClef across the backs of his ankles. The Intelligence agent screamed and toppled, his hamstrings cut, his legs useless. The chromed pistol flew from his fingers and landed on the floor out of reach.

“Annika,” whispered Peyton.

She came to kneel by his side. He felt her blonde hair brush his face.

“What is it, Daddy?” She was crying. Tears fell from her eyes and splashed his cheeks.

“Was… Was I a good father?”

“You were the best father, Daddy,” she said. “You always will be.”

“I… love you,” he said. He closed his eye. He couldn’t keep it open anymore. He became very still.

“I love you too, Daddy,” she said. She kissed his forehead, stood, and walked to where VanClef’s pistol had fallen. Picking this up, she studied it for a moment, made sure the safety was off, and stood before VanClef. The government man was inching across the floor, trying to drag himself, leaving a pair of blood trials from his severed hamstrings.

“You killed him,” she said.

VanClef’s tried to look over his own shoulder as he crawled. “Annika, no,” he said. “No! Don’t do this. We need each other. We can help each other. You can be so much more! Do so much more! You just need the right guide.”

She aimed the pistol at his forehead, holding it with both hands. “You’re mean,” she said. “You’re the meanest man in the whole world. I hate you. It’s wrong to hate. But you killed my Daddy and I hate you. And I’m going to fix you.”

“Annika!” he said. “Please–”

“You don’t have a kind heart,” she said. “But I’m going to give you one.”

VanClef’s eyes grew wide. “No–” he began.

Annika pulled the trigger. She pulled it again. She pulled it a third time.

She kept pulling it until the pistol was empty.