Rachel Manija Brown's Blog, page 60

January 15, 2022

Talargain, by Joyce Gard

This is the book I thought was a Northumberland selkie story. It's actually 95% a historical Northumberland coming of age with seals and a kind of rationalized selkie element, and 5% selkie (who is actually a ghost). It's quite good and unusual, as you can see from that description, but more of a vivid historical than a numinous fantasy.

The frame story is set in present-day (1960s) Northumberland, from the point of view of a girl whose family has moved back there, as it was her mother's childhood home. She meets Talargain, a selkie who lived as a man the time of King Ecgfrith and Aldfrith (late 600s). (In context he seems more like a ghost than an immortal.) He tells her the story of his life, which makes up 95% of the book.

I loved the brief portions of the book set in present-day Northumberland - they're even more atmospheric than the historical parts, and those are plenty atmospheric.

The main story is the coming of age of Talargain, whose feud with another boy gains political importance as they both grow up, who befriends the local monks, who learns that he was adopted as a baby after his dying mother was rescued from a shipwreck, and who loves the seals.

He and his mother make a highly convincing early scuba suit out of sealskin (from a seal who was found dead - he would never kill one) and other materials so he can swim with them, and he befriends them. They're not magical seals - he first meets one because the monks have already befriended her - but they're unusually friendly to him, and he has a lot of delightful small-scale adventures swimming with them.

The political tensions, the feud, his kinship with the seals, and his true parentage all come together when he's recruited for a dangerous mission to convey a message of peace.

This is a highly detailed, likable, atmospheric historical with light fantasy elements. The characters have plausible historical attitudes - they're not modern people in period dress - but Gard shows how beliefs and personalities vary within cultural frameworks.

Talargain and his sister Angharad don't fit into the usual gender roles of the period, but in a plausible manner and in a way which has consequences, both negative and positive. Angharad is sent off to another household learn to be more ladylike; she and the girl who was supposed to be a good influence on her end up both doing all the tomboy things Angharad used to do with Talargain, and learning to read and write. Talargain's lack of interest in the normal boy activities means he doesn't have friends among the boys in his own community, which causes problems for him later on.

I enjoyed this a lot and will keep a lookout for Gard's other books.

[image error]

comments

comments

The frame story is set in present-day (1960s) Northumberland, from the point of view of a girl whose family has moved back there, as it was her mother's childhood home. She meets Talargain, a selkie who lived as a man the time of King Ecgfrith and Aldfrith (late 600s). (In context he seems more like a ghost than an immortal.) He tells her the story of his life, which makes up 95% of the book.

I loved the brief portions of the book set in present-day Northumberland - they're even more atmospheric than the historical parts, and those are plenty atmospheric.

The main story is the coming of age of Talargain, whose feud with another boy gains political importance as they both grow up, who befriends the local monks, who learns that he was adopted as a baby after his dying mother was rescued from a shipwreck, and who loves the seals.

He and his mother make a highly convincing early scuba suit out of sealskin (from a seal who was found dead - he would never kill one) and other materials so he can swim with them, and he befriends them. They're not magical seals - he first meets one because the monks have already befriended her - but they're unusually friendly to him, and he has a lot of delightful small-scale adventures swimming with them.

The political tensions, the feud, his kinship with the seals, and his true parentage all come together when he's recruited for a dangerous mission to convey a message of peace.

This is a highly detailed, likable, atmospheric historical with light fantasy elements. The characters have plausible historical attitudes - they're not modern people in period dress - but Gard shows how beliefs and personalities vary within cultural frameworks.

Talargain and his sister Angharad don't fit into the usual gender roles of the period, but in a plausible manner and in a way which has consequences, both negative and positive. Angharad is sent off to another household learn to be more ladylike; she and the girl who was supposed to be a good influence on her end up both doing all the tomboy things Angharad used to do with Talargain, and learning to read and write. Talargain's lack of interest in the normal boy activities means he doesn't have friends among the boys in his own community, which causes problems for him later on.

I enjoyed this a lot and will keep a lookout for Gard's other books.

[image error]

comments

comments

Published on January 15, 2022 13:31

January 12, 2022

Old Children's Book Poll

Here are some old children's books I have acquired. Please vote for which I should read next (or which I should avoid.) If you've read any of them, what did you think?

View Poll: Old Children's Book Poll

comments

comments

View Poll: Old Children's Book Poll

comments

comments

Published on January 12, 2022 12:30

Nod, by Adrian Barnes

An intriguing and compelling but borderline parodically grimdark novel about apocalypse by sleep deprivation. It's like a reading a car crash. I couldn't put it down.

Even before the apocalypse, the narrator, Paul, hates literally everything and everyone except his doomed wife Tanya. Even the metaphors are ultra grim. Here's a sample of Paul's pre-apocalypse outlook on life; he writes scholarly books on etymology.

My agent, still unsure about me after seven years of contractual bondage, was always pushing for an Eats Shoots and Leaves sort of mass placebo, the idea being to try to trick the public into consuming something inherently dry and bland by dusting it with MSG. I never delivered that book. I never refused, mind you—just went ahead and wrote other books which, published through unambitious presses, sold just enough copies to shut-ins and fuzzy-sweatered fussbudgets to draw forth more grudging grants, more painful teaching gigs, and to continue the damp seepage of royalties into my checking account.

In a single, typical paragraph, Paul drips contempt and hatred for his agent, having an agent, popular books on language, people who read popular books on language, etymology, his publishers, people who read his books, people who give him grants, teaching, and the money he makes writing.

Another moment which was emblematic of the novel's tone was when the apocalypse has begun and Paul and Tanya decide to have one last hurrah by eating at a restaurant. They choose a restaurant which is kind of a couple in-joke, because it has terrible food and bad service and they hate it.

And then the most people became unable to sleep overnight, became psychotic, and died (after setting up batshit cults because of course they did), but a small minority did continue sleeping. Paul was one of them. The adult Sleepers all dreamed blissfully of a beautiful golden light. The child Sleepers stopped talking and communicating in any way, and seemed weirdly calm.

None of this is ever explained. Possibly it would have been in Nod's planned sequels, Pod and God, but sadly Barnes died of cancer before writing them.

The batshit cult tortures and murders Sleepers and paints things bright yellow, including the heads of murdered Sleepers. Paul reluctantly protects a Sleeper child after Tanya goes insane, witnesses Seattle getting nuked, and prevents the insane last survivor of a nuclear warship from setting off a nuke. He then barricades himself and the child in his apartment from a crazed mob outside, lowers her down from the window on a rope, and lies down to sleep and be torn apart when the mob breaks in.

When he falls asleep/commits suicide, the book ends in mid-sentence.

There was an excellent sequel story this Yuletide, which is dark but not in this particular mode of grimdark, marginalia by StopTalkingAtMe.

Nod

[image error]

comments

comments

Even before the apocalypse, the narrator, Paul, hates literally everything and everyone except his doomed wife Tanya. Even the metaphors are ultra grim. Here's a sample of Paul's pre-apocalypse outlook on life; he writes scholarly books on etymology.

My agent, still unsure about me after seven years of contractual bondage, was always pushing for an Eats Shoots and Leaves sort of mass placebo, the idea being to try to trick the public into consuming something inherently dry and bland by dusting it with MSG. I never delivered that book. I never refused, mind you—just went ahead and wrote other books which, published through unambitious presses, sold just enough copies to shut-ins and fuzzy-sweatered fussbudgets to draw forth more grudging grants, more painful teaching gigs, and to continue the damp seepage of royalties into my checking account.

In a single, typical paragraph, Paul drips contempt and hatred for his agent, having an agent, popular books on language, people who read popular books on language, etymology, his publishers, people who read his books, people who give him grants, teaching, and the money he makes writing.

Another moment which was emblematic of the novel's tone was when the apocalypse has begun and Paul and Tanya decide to have one last hurrah by eating at a restaurant. They choose a restaurant which is kind of a couple in-joke, because it has terrible food and bad service and they hate it.

And then the most people became unable to sleep overnight, became psychotic, and died (after setting up batshit cults because of course they did), but a small minority did continue sleeping. Paul was one of them. The adult Sleepers all dreamed blissfully of a beautiful golden light. The child Sleepers stopped talking and communicating in any way, and seemed weirdly calm.

None of this is ever explained. Possibly it would have been in Nod's planned sequels, Pod and God, but sadly Barnes died of cancer before writing them.

The batshit cult tortures and murders Sleepers and paints things bright yellow, including the heads of murdered Sleepers. Paul reluctantly protects a Sleeper child after Tanya goes insane, witnesses Seattle getting nuked, and prevents the insane last survivor of a nuclear warship from setting off a nuke. He then barricades himself and the child in his apartment from a crazed mob outside, lowers her down from the window on a rope, and lies down to sleep and be torn apart when the mob breaks in.

When he falls asleep/commits suicide, the book ends in mid-sentence.

There was an excellent sequel story this Yuletide, which is dark but not in this particular mode of grimdark, marginalia by StopTalkingAtMe.

Nod

[image error]

comments

comments

Published on January 12, 2022 10:12

January 11, 2022

Ella of All-of-a-Kind Family, by Sydney Taylor

The final book in the All-of-a-Kind Family series, Ella is unique in that it focuses primarily on Ella rather than the family as a whole.

Ella is now eighteen and wants to marry Jules, but is also interested in a singing career. Through a distinctly shoe-horned-in mechanism (“I just now remembered that I have a cousin I never mentioned before who’s in showbiz and can get you an audition!”) she gets an audition and an offer of a career in a traveling show. Jules is upset because she’s putting her career over marrying him; this goes over particularly badly because this is happening during the suffrage movement, which their father opposes though not in a mean way.

Ella does not enjoy doing the traveling show, which is hard and uncomfortable work in a very realistic manner, and quits. But luckily, she gets another sudden offer, to sing in a New York choir, and so is able to sing and marry Jules too.

Ella has a somewhat YA feel and is the shortest of the series, with a somewhat abrupt ending. That plus the convenient plotting makes it feel slight in a way the other books don’t, even though it’s ostensibly dealing with more important topics.

My favorite part has nothing to do with the overall plot, but is when Charlotte and Gertie (now 10 and 8) babysit a younger girl and get the brilliant idea of giving her bangs, but one side keeps being shorter than the other. Attempts to even it out go exactly as you know they will if you ever tried to trim your own bangs.

Ella of All-of-a-Kind Family (All-of-a-Kind Family Classics)

[image error]

comments

comments

Ella is now eighteen and wants to marry Jules, but is also interested in a singing career. Through a distinctly shoe-horned-in mechanism (“I just now remembered that I have a cousin I never mentioned before who’s in showbiz and can get you an audition!”) she gets an audition and an offer of a career in a traveling show. Jules is upset because she’s putting her career over marrying him; this goes over particularly badly because this is happening during the suffrage movement, which their father opposes though not in a mean way.

Ella does not enjoy doing the traveling show, which is hard and uncomfortable work in a very realistic manner, and quits. But luckily, she gets another sudden offer, to sing in a New York choir, and so is able to sing and marry Jules too.

Ella has a somewhat YA feel and is the shortest of the series, with a somewhat abrupt ending. That plus the convenient plotting makes it feel slight in a way the other books don’t, even though it’s ostensibly dealing with more important topics.

My favorite part has nothing to do with the overall plot, but is when Charlotte and Gertie (now 10 and 8) babysit a younger girl and get the brilliant idea of giving her bangs, but one side keeps being shorter than the other. Attempts to even it out go exactly as you know they will if you ever tried to trim your own bangs.

Ella of All-of-a-Kind Family (All-of-a-Kind Family Classics)

[image error]

comments

comments

Published on January 11, 2022 11:47

January 10, 2022

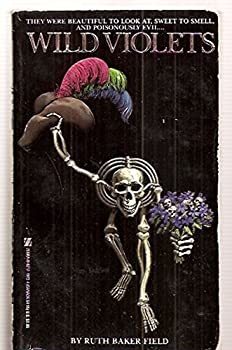

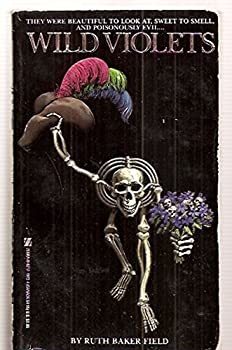

Wild Violets, by Ruth Baker Field

Isn't that a great cover? Straight outta Paperbacks From Hell! In real life the skeleton is embossed. A lot of love and thought and playfulness went into that cover. Doesn't it make you expect something fun?

The book has a great opening line, too:

Kramer Willinger planned from the beginning to place Suzanne Strand's head in the bed of wild violets.

Unfortunately, after that crackerjack opening, the book became something totally unexpected to me, though apparently not to ten clever guessers of my poll. About two pages in, it flashed back to Kramer Willinger's childhood and became wall to wall incest of a most unappealing variety: 10 year old son fondling mother while she's unconscious from sleeping pills.

I skimmed, hopeful of dashing courtly skeletons or at least some beheadings, but just got Kramer's life story, which consisted of still yet more porn, sometimes now including women other than his mother but always returning to his mother. And not even good porn:

He gave another thrust.

The bed went urump... urump.

He does become a serial killer but the author clearly had even less interest in that than I did, because my skim-estimate is that the book is 85% the bed went urump... urump, 10% the traumatically mute mom trying to remember exactly what happened when she learned Judo and her husband mysteriously fell off a cliff, and 5% murder.

Very disappointing. I would love to read the book that belongs with the cover. Literally any of my poll choices but the right one would have been better. If I wanted underage incest (I don't), I'd have had a lot more fun with The Romance of Lust and its doodles and bubbies.

A Goodreads review: This is a cautionary tale about how judo throwing a terrible husband off a cliff may cause a son to love his mom WAYYYY too much.

I hope some of you read the skeleton cozy mysteries! They are guaranteed to be better.

comments

comments

The book has a great opening line, too:

Kramer Willinger planned from the beginning to place Suzanne Strand's head in the bed of wild violets.

Unfortunately, after that crackerjack opening, the book became something totally unexpected to me, though apparently not to ten clever guessers of my poll. About two pages in, it flashed back to Kramer Willinger's childhood and became wall to wall incest of a most unappealing variety: 10 year old son fondling mother while she's unconscious from sleeping pills.

I skimmed, hopeful of dashing courtly skeletons or at least some beheadings, but just got Kramer's life story, which consisted of still yet more porn, sometimes now including women other than his mother but always returning to his mother. And not even good porn:

He gave another thrust.

The bed went urump... urump.

He does become a serial killer but the author clearly had even less interest in that than I did, because my skim-estimate is that the book is 85% the bed went urump... urump, 10% the traumatically mute mom trying to remember exactly what happened when she learned Judo and her husband mysteriously fell off a cliff, and 5% murder.

Very disappointing. I would love to read the book that belongs with the cover. Literally any of my poll choices but the right one would have been better. If I wanted underage incest (I don't), I'd have had a lot more fun with The Romance of Lust and its doodles and bubbies.

A Goodreads review: This is a cautionary tale about how judo throwing a terrible husband off a cliff may cause a son to love his mom WAYYYY too much.

I hope some of you read the skeleton cozy mysteries! They are guaranteed to be better.

comments

comments

Published on January 10, 2022 11:19

January 8, 2022

Courtly Skeleton Poll

Published on January 08, 2022 09:24

January 7, 2022

Saturday, the Twelfth of October, by Norma Fox Mazer

A classic time-travel book from 1975, back in print via Lizzie Skurnick Books. I love the title. It's strangely haunting.

Fourteen-year-old Zan (short for Alexandra) doesn't fit in and worries that she hasn't yet gotten her period. She's fascinated when her history teacher brings up the concept of time as a river, but when she tries to talk to him more about it, he blows her off. She gets mugged and assaulted, and her aunt blows her off. Her brother finds her diary and reads her entries thinking about her body and sex aloud to his friends, humiliating her, and her mother blows her off.

The sheer force of her misery sends her back in time to the Stone Age, where she falls in with a tribe preparing for the Susuru, a month-long ritual celebrating all the girls who have begun menstruating since last year's Susuru. Zan has an extremely rocky adjustment and goes catatonic for a while, but is brought out of it by the tribe's wise woman. She learns the language, makes friends, and becomes an accepted member of the tribe even though, like in her previous life, she was also an outsider.

Zan's life with the cave people makes up the meat of the book, and it's very good. Mazer depicts them and their lives as idyllic in some ways (they spend a lot of time playing and resting, they gather eggs and bugs but don't hunt and there's food all around them, and there's no sexism or war), and the opposite of idyllic in others (no modern medicine, one of the boys was rescued by his mother from being killed because he has a craniofacial malformation, the food is gross as they don't wash anything and the only thing they cook is worms), but above all, as believable individuals in a plausible cultural setting.

As far as I could tell the culture was mostly imagined rather than researched, but it does have a bit of a Clan of the Cave Bear feel minus the rape and food you'd actually want to eat. Zan does develop a taste for raw eggs though.

But all good or even semi-good things must come to an end... ( Read more... )

Excellent anthropological cave people narrative enclosed in an awesomely depressing frame story with an ending that isn't just sad in the usual nature of time travel stories, but piles on extra misery from an unanticipated direction. Well, it was the 70s.

Content notes: Child death, cultural practice of killing babies with birth defects, violence, humiliation, ambiguously sexual assault during a mugging, bad parenting, bad therapy, bad teaching, graphic bug eating.

Saturday, The Twelfth Of October

First link goes to the Kindle edition, second to the original paper book. I like the second cover better.

[image error]

[image error]

comments

comments

Fourteen-year-old Zan (short for Alexandra) doesn't fit in and worries that she hasn't yet gotten her period. She's fascinated when her history teacher brings up the concept of time as a river, but when she tries to talk to him more about it, he blows her off. She gets mugged and assaulted, and her aunt blows her off. Her brother finds her diary and reads her entries thinking about her body and sex aloud to his friends, humiliating her, and her mother blows her off.

The sheer force of her misery sends her back in time to the Stone Age, where she falls in with a tribe preparing for the Susuru, a month-long ritual celebrating all the girls who have begun menstruating since last year's Susuru. Zan has an extremely rocky adjustment and goes catatonic for a while, but is brought out of it by the tribe's wise woman. She learns the language, makes friends, and becomes an accepted member of the tribe even though, like in her previous life, she was also an outsider.

Zan's life with the cave people makes up the meat of the book, and it's very good. Mazer depicts them and their lives as idyllic in some ways (they spend a lot of time playing and resting, they gather eggs and bugs but don't hunt and there's food all around them, and there's no sexism or war), and the opposite of idyllic in others (no modern medicine, one of the boys was rescued by his mother from being killed because he has a craniofacial malformation, the food is gross as they don't wash anything and the only thing they cook is worms), but above all, as believable individuals in a plausible cultural setting.

As far as I could tell the culture was mostly imagined rather than researched, but it does have a bit of a Clan of the Cave Bear feel minus the rape and food you'd actually want to eat. Zan does develop a taste for raw eggs though.

But all good or even semi-good things must come to an end... ( Read more... )

Excellent anthropological cave people narrative enclosed in an awesomely depressing frame story with an ending that isn't just sad in the usual nature of time travel stories, but piles on extra misery from an unanticipated direction. Well, it was the 70s.

Content notes: Child death, cultural practice of killing babies with birth defects, violence, humiliation, ambiguously sexual assault during a mugging, bad parenting, bad therapy, bad teaching, graphic bug eating.

Saturday, The Twelfth Of October

First link goes to the Kindle edition, second to the original paper book. I like the second cover better.

[image error]

[image error]

comments

comments

Published on January 07, 2022 10:43

January 6, 2022

Tales of a Fourth-Grade Nothing, by Judy Blume

In the run-up to Yuletide, I set out to re-read this series, which I think I last read when I was eleven, in order to beta-read NaomiK's Yuletide Fudge story, Fudge Ripple. This was a complete failure, as I'm still reading the series now to fully appreciate the story!

In this book, Peter Hatcher leads a very put-upon life due to his maniacal baby brother Fudge. His big consolation is his pet turtle Dribble. If you've never read or osmosed this book, I'm sure you can still guess the general outline of what happens.

My favorite Judy Blume books were her lesser-known ones, like Tiger Eyes and It's Not the End of the World. This book mildly traumatized me as a kid because of the particularly upsetting pet death in which FUDGE EATS DRIBBLE. I don't think I ever re-read it, so I was surprised by how familiar it was when I did thirty years later.

A lot of the book is genuinely funny, but it's overshadowed for me by the looming dread of Dribble's fate. Fudge repeatedly messes with Dribble, Peter asks his parents for a lock on his bedroom door, and his parents refuse because they think good families don't shut each other out. Fudge swallows Dribble and is rushed to the ER, and Peter is given a puppy who he names Turtle. I was relieved to see later in the series that Peter does get a lock on his door.

One thing I was surprised by was how young Fudge is. He turns three in the course of the story. I'd remembered him as four or five, which is still way too young for me to hold a grudge but it does make the turtle-eating make more sense and feel less deliberate. Not letting Peter lock his door was still spectacularly bad parenting though - they knew Fudge was messing with Peter's tiny pet, and the result was that Fudge killed the pet and put himself in danger too. I hope they felt guilty.

I can see why it's a classic - it's still very funny, Peter and his friends are very relatable, and the New York setting is vivid - but I liked Superfudge a lot more because it doesn't involve parental negligence leading to your brother eating your pet!

Fudge does take his new infant sister out of her crib and stick her in a closet though, which is not discovered for hours. The Hatchers are lucky he didn't drop her down the incinerator.

[image error]

comments

comments

In this book, Peter Hatcher leads a very put-upon life due to his maniacal baby brother Fudge. His big consolation is his pet turtle Dribble. If you've never read or osmosed this book, I'm sure you can still guess the general outline of what happens.

My favorite Judy Blume books were her lesser-known ones, like Tiger Eyes and It's Not the End of the World. This book mildly traumatized me as a kid because of the particularly upsetting pet death in which FUDGE EATS DRIBBLE. I don't think I ever re-read it, so I was surprised by how familiar it was when I did thirty years later.

A lot of the book is genuinely funny, but it's overshadowed for me by the looming dread of Dribble's fate. Fudge repeatedly messes with Dribble, Peter asks his parents for a lock on his bedroom door, and his parents refuse because they think good families don't shut each other out. Fudge swallows Dribble and is rushed to the ER, and Peter is given a puppy who he names Turtle. I was relieved to see later in the series that Peter does get a lock on his door.

One thing I was surprised by was how young Fudge is. He turns three in the course of the story. I'd remembered him as four or five, which is still way too young for me to hold a grudge but it does make the turtle-eating make more sense and feel less deliberate. Not letting Peter lock his door was still spectacularly bad parenting though - they knew Fudge was messing with Peter's tiny pet, and the result was that Fudge killed the pet and put himself in danger too. I hope they felt guilty.

I can see why it's a classic - it's still very funny, Peter and his friends are very relatable, and the New York setting is vivid - but I liked Superfudge a lot more because it doesn't involve parental negligence leading to your brother eating your pet!

Fudge does take his new infant sister out of her crib and stick her in a closet though, which is not discovered for hours. The Hatchers are lucky he didn't drop her down the incinerator.

[image error]

comments

comments

Published on January 06, 2022 11:45

January 5, 2022

The Box-Car Children, by Gertrude Chandler Warner

This is the original book published in 1924. I have no idea how I missed this for so long, because it’s SO up my alley.

Four children are left alone when their alcoholic father dies, their mother having died long ago. Their father told them their only relative is their grandfather and he’s mean, so the kids flee into the night rather than be sent to him. That is the last time anyone will think of their father; this is not a book about grief and trauma.

The kids find an abandoned boxcar in the woods near a town, and proceed to transform it into a cozy home. The oldest boy works in town to make money for food, and events eventually reveal that their grandfather is in that very town and is a very nice person who will give them a good home. But really the story is about four kids living cozily in a boxcar in the woods, making stews and rescuing cups from the dump and digging a swimming hole. If that is something you like, you will certainly enjoy this story.

I know this has a bazillion sequels. What are the sequels about? Do they also feature boxcar homemaking coziness?

comments

comments

Four children are left alone when their alcoholic father dies, their mother having died long ago. Their father told them their only relative is their grandfather and he’s mean, so the kids flee into the night rather than be sent to him. That is the last time anyone will think of their father; this is not a book about grief and trauma.

The kids find an abandoned boxcar in the woods near a town, and proceed to transform it into a cozy home. The oldest boy works in town to make money for food, and events eventually reveal that their grandfather is in that very town and is a very nice person who will give them a good home. But really the story is about four kids living cozily in a boxcar in the woods, making stews and rescuing cups from the dump and digging a swimming hole. If that is something you like, you will certainly enjoy this story.

I know this has a bazillion sequels. What are the sequels about? Do they also feature boxcar homemaking coziness?

comments

comments

Published on January 05, 2022 12:02

January 4, 2022

The Worm and his Kings, by Hailey Piper

A short, inventive cosmic horror novel with a likable protagonist and characters who are mostly female, queer, trans, or all of the above. I say “female” rather than “women” because some of them aren’t human.

Monique is a young homeless woman searching for her older girlfriend Donna, who like many homeless women has recently vanished. Rumors say they’ve fallen prey to “Gray Hill,” a serial killer. But when Monique finally encounters Gray Hill, it’s not a serial killer in any conventional sense, but a monster. Rather than running, she follows the creature in the hope of finding Donna, and discovers a bizarre underground cult that worships “the Worm.”

This fast-paced, quirky book is a lot of fun and takes some unexpected turns. I enjoyed the startling yet oddly satisfying ending, and the unusual nature of "the Worm." Also the commentary on gender, glowing fungus, cool creatures, and an incredibly determined heroine.

It's more a horror novel with trans/queer/female characters than a novel about being trans/queer/female that's also horror. The non-horror elements in the content notes are an integral part of the story, but occupy a relatively small page-space.

Content notes: gender dysphoria, scars from a botched gender affirmation surgery, existence of homophobia and transphobia, body horror, horror-style violence.

The Worm and His Kings

[image error]

comments

comments

Monique is a young homeless woman searching for her older girlfriend Donna, who like many homeless women has recently vanished. Rumors say they’ve fallen prey to “Gray Hill,” a serial killer. But when Monique finally encounters Gray Hill, it’s not a serial killer in any conventional sense, but a monster. Rather than running, she follows the creature in the hope of finding Donna, and discovers a bizarre underground cult that worships “the Worm.”

This fast-paced, quirky book is a lot of fun and takes some unexpected turns. I enjoyed the startling yet oddly satisfying ending, and the unusual nature of "the Worm." Also the commentary on gender, glowing fungus, cool creatures, and an incredibly determined heroine.

It's more a horror novel with trans/queer/female characters than a novel about being trans/queer/female that's also horror. The non-horror elements in the content notes are an integral part of the story, but occupy a relatively small page-space.

Content notes: gender dysphoria, scars from a botched gender affirmation surgery, existence of homophobia and transphobia, body horror, horror-style violence.

The Worm and His Kings

[image error]

comments

comments

Published on January 04, 2022 14:17

comments

comments