Jeffrey L. Seglin's Blog, page 48

October 16, 2016

Whose seeds are these? I think I know

On her daily morning walks through her neighborhood, a woman in Boston has been admiring the large sunflower plants that some neighbors have planted in their front yards. The sunflowers of one neighbor in particular lean out over the public sidewalk, which the Boston reader uses each morning.

"A few years ago, I remember that there was a spate of sunflower robberies," the Boston reader writes. "Someone was going through the neighborhood at night and cutting off the sunflowers, presumably to sell them, use them for home decor, or just be vandals."

"I'd never do anything like that," she continues. And apparently, the great sunflower robbery epidemic has been contained.

But lately, as the sunflowers begin to complete their blooms, she's noticed that many are dropping some of their seeds onto the ground. Many of these sunflower seeds are landing on the public sidewalk.

"Would it be wrong for me to scoop up the seeds and take them home?" she asks.

Years ago, I had a similar question from a reader in Cypress, Calif. She wondered if it was OK to pick lemons off a neighbor's lemon tree if the branches swung out from the tree owner's yard and across the public sidewalk. It turns out that the tree owner was likely in violation of a town ordinance that forbade allowing your trees or shrubs to block public walkways. If she had picked a lemon off of her neighbor's tree, she might not have been on the wrong side of the law, but I suggested that the right thing was to ask the owner before picking.

The sunflower case is a bit different, however. While I'd still argue that the right thing to do is to ask the owner of the sunflowers if it is OK to scoop up seeds from his plants that fall on the walk -- once they hit the walk and are no longer attached to the plant -- it would be OK for her to take a handful and feel no guilt.

The lemons attached to the neighbor's tree in California were still attached to the owner's tree. The sunflower seeds in Boston are not still attached to the owner's plant.

Even if it is OK to scoop up some sunflower seeds, however, is that the best right thing for the Boston reader to do? She might determine that if the seeds are left to lie on a public walk that they are fair game, but this is, after all, her neighborhood. If she puts herself in the shoes of her sunflower-owning neighbor, she might ask herself how she would feel if she saw a neighbor making off with seeds from her beautiful flowers. Her neighbor may want to gather up his own seeds for future use. The only way to know for certain is for the Boston reader to ask him.

The right thing would be for the Boston reader to wait until she sees her neighbor and then ask him if it's OK if she takes some of the dropped sunflower seeds. That's likely to be want the Boston reader would hope any neighbor of hers might do if the seeds came from her sunflowers.

Jeffrey L. Seglin, author of The Simple Art of Business Etiquette: How to Rise to the Top by Playing Nice, is a lecturer in public policy and director of the communications program at Harvard's Kennedy School. He is also the administrator of www.jeffreyseglin.com, a blog focused on ethical issues.

Do you have ethical questions that you need answered? Send them to rightthing@comcast.net.

F ollow him on Twitter: @jseglin

(c) 2015 JEFFREY L. SEGLIN. DISTRIBUTED BY TRIBUNE CONTENT AGENCY, LLC.

Published on October 16, 2016 07:23

October 9, 2016

Just say no to the boss's spouse's request

An employee for a business has held her job for five years. She's done well on the job, performing her duties to her boss's satisfaction, and taking on roles of increasing responsibility. She -- let's call her Tina -- loves her job at a business that is privately owned by a wealthy gentleman.

Several weeks ago, the owner sent out an email to the employees that his wife had taken on responsibility for running a series of nonprofit events in the community. There were many opportunities for employees to volunteer to help with the cause. They were given a heads up that his wife might be in touch.

Sure enough, Tina was contacted by the owner's wife, who asked her if she could run one of the activities. Tina learned more about the nonprofit and what the owner's wife had in mind for her. She realized that she liked the work the nonprofit was trying to do. But she also realized that the boss's wife was asking her to run this event on her day off from work on her own time.

Many years ago, I wrote about a program that a major bank chain ran with its employees asking them to adopt-an-ATM in their neighborhood and then making sure that those ATM areas were kept clean. The adoptive employees were not paid for their efforts. The program drew the scrutiny of some labor officials who found the practice to violate wage and hour law. Many employees who loved their bank would likely have picked up litter in an ATM area without having a formal program. Those employees a little less enamored of the company might have felt a bit more coerced into saying yes to the plan.

Tina didn't want to disappoint her owner's wife, but she also really liked the idea of getting paid for when she worked and she enjoyed her days off. She didn't want to disappoint the owner who signed her paycheck. She was fairly certain she would not be punished for saying "no" to the request, but she wondered if saying no was in her best interest if she wanted to continue advancing at the company at the rate with which she had been doing.

If Tina wants to say no, she should say no. She can graciously tell the owner's wife that she likes the work the nonprofit is doing, but that she can't participate on the day of the event. If she wants to help out and volunteer, she should say yes. But she should fight the urge to feel like she must say yes, as strong as that urge might be.

The right thing would have been for the owner not to have mixed business and his wife's outside efforts and put his employees in the position of having to say no to her requests. It's like saying no to the boss asking employees to buy Girl Scout cookies from his kid -- only a bit tougher since the request to Tina involved an entire unpaid day, rather than simply shelling out $5 for a box of Thin Mints.

Company owners and bosses should respect their employees and their time and not put them in the awkward position of having to decide if saying no to an outside, unpaid event will affect their job security.

Jeffrey L. Seglin, author of The Simple Art of Business Etiquette: How to Rise to the Top by Playing Nice, is a lecturer in public policy and director of the communications program at Harvard's Kennedy School. He is also the administrator of www.jeffreyseglin.com, a blog focused on ethical issues.

Do you have ethical questions that you need answered? Send them to rightthing@comcast.net.

F ollow him on Twitter: @jseglin

(c) 2015 JEFFREY L. SEGLIN. DISTRIBUTED BY TRIBUNE CONTENT AGENCY, LLC.

Published on October 09, 2016 05:44

October 2, 2016

Ceramics collectors should stop short of making knock-offs

A long-time reader of the column from Ohio and her husband used to collect a series of ceramic sculptures. P.A. writes that the company that made the sculptures created a series of villages including Dickens Village, the North Pole, and others, but she points out that other companies make similar villages.

Recently, P.A., joined some Facebook pages created by fellow collectors as well as a buy-and-sell page for the collections. She's discovered that there are a few people who seemingly don't want to pay the going rate for some of the items so they are making their own versions.

"Some are molding the houses out of clay," she writes. "Others are using 3-D printers. They are trying to create exact copies of the original pieces."

P.A. points out that some are creating the pieces for their own enjoyment, while others are selling their pieces. Still others are making new pieces of their own creation.

The people who are selling the pieces they've made to be "exact copies" are telling prospective buyers that they are copies and not originals. "I don't see them as trying to swindle people with fakes," writes P.A., "although you can really tell the difference pretty easily anyway."

"Is this copyright infringement?" asks P.A. "Is what they are doing unethical?"

Sure, the copies might have taken a lot of work to create, but that also doesn't take away from the fact that they are copying a design that rightfully belongs to someone else. (Painting a replica of someone else's original artwork also can take a lot of work. Trying to sell that copy also infringes on someone else's creation.)

The ceramic items that others create to supplement the villages they collect seem to fall into a different category. If such items are replicas of existing pieces, then it seems fair game to go ahead and create them or sell them as long as they are clearly distinguishing these items as things they make rather than new items released by the company creating the villages.

If the company encourages collectors of the items it sells to make copies, then they should feel free to do so. But it should be left to the company to decide if it wants to do this. (So far, it seems clear from its website and other materials that it doesn't want to.) The copiers instead might consider creating original pieces to sell.

The right thing for the collectors is to continue to enjoy collecting whatever villages and pieces they want to collect, but to stop short of creating knock offs to cut costs or make some extra money.

Jeffrey L. Seglin, author of The Simple Art of Business Etiquette: How to Rise to the Top by Playing Nice, is a lecturer in public policy and director of the communications program at Harvard's Kennedy School. He is also the administrator of www.jeffreyseglin.com, a blog focused on ethical issues.

Do you have ethical questions that you need answered? Send them to rightthing@comcast.net.

F ollow him on Twitter: @jseglin

(c) 2015 JEFFREY L. SEGLIN. DISTRIBUTED BY TRIBUNE CONTENT AGENCY, LLC.

Published on October 02, 2016 06:11

September 25, 2016

When companies alarm customers needlessly

When A.S. received a letter from the insurance company that held the policy on her house, she was concerned. In the first paragraph of the letter, it indicated that the company wanted to clarify how it handled late payments.

Rarely had A.S. received anything in the mail from her insurance company other than an invoice for the cost of that year's insurance. But this letter raised her concern that perhaps she had missed making an insurance payment since there was nothing in the letter to indicate whether her account was paid in full. There was a note that customers could shift to an automatic payment system where funds could be withdrawn directly from their checking accounts.

A.S. had never had any interest in setting up an automatic payment plan. She liked writing a check after the invoice arrived in the mail. But she feared that perhaps a payment had not been received, or, even worse, that she had neglected to pay on time even when she thought she had.

After calling her insurance broker, A.S. was told that she indeed was not late with a payment and "never had been." The broker pointed out that in the letter it indicated that the lateness is not an issue for most customers. But because of the regulatory nature of the industry, it felt obligated to send out a letter to all customers.

"They've been my insurance broker for more than 20 years," writes A.S. "They have all of my records on file. They knew I wasn't late with my payment and that I'd never been late with a payment. Shouldn't they have included a notice along with the letter that indicated I had paid on time? Even if they feel obligated to send a letter like this, isn't that the ethical thing to do to avoid alarming customers who always have paid on time?"

While A.S. has every right to be annoyed with her insurance company for not anticipating that its letter about the change-in-late-payment policy might confuse or alarm some of its customers, the company didn't cross any ethical line.

By meeting its obligation to send the letter, the letter writers did what they felt was needed to keep customers abreast of a policy change. The insurance company did what it believes the regulatory agencies governing it required it to do.

But by not including a note with each letter to indicate which policy holders were late and which weren't, the insurance company lost an opportunity to engage in good customer service. If longtime clients such as A.S. had received a statement of their accounts along with the policy change letter, any unnecessary concern could have been alleviated and the number of phone calls to the agency would have been cut down significantly.

Certainly, the right thing for any financial service company is to comply with the regulations that govern it. But there are times when companies, if they want to solidify their relationships with new or longtime customers, should take the extra step of doing what's in their customers' best interests. This should have been one of those times.

Jeffrey L. Seglin, author of The Simple Art of Business Etiquette: How to Rise to the Top by Playing Nice, is a lecturer in public policy and director of the communications program at Harvard's Kennedy School. He is also the administrator of www.jeffreyseglin.com, a blog focused on ethical issues.

Do you have ethical questions that you need answered? Send them to rightthing@comcast.net.

F ollow him on Twitter: @jseglin

(c) 2015 JEFFREY L. SEGLIN. DISTRIBUTED BY TRIBUNE CONTENT AGENCY, LLC.

Published on September 25, 2016 07:04

September 18, 2016

If I won't eat a slice, should I offer one to you?

Lil, a reader who prefers I not use her real name, works for an organization that allows its employees to accept small gifts from clients or families of clients, as long as they do not exceed $25 in value. Often these include baked goods or other homemade treats.

Last December, Lil received banana bread that was baked by one of her client's mothers. Lil knew the family well and writes that she was concerned about the "cleanliness" of the kitchen in which the banana bread was baked. Rather than decline the gift because of her concern, Lil decided to accept it and graciously thanked the grandparent.

Lil writes that she hesitated about whether to dispose of the banana bread by throwing it away. It seemed "a waste of food" to her to do so.

Lil decided to leave the banana bread out in her workplace's common area for any of her colleagues who wanted to have a slice.

"None of them knew the family, so they had no reason to be concerned about cleanliness," Lil writes.

Within an hour, the banana bread was consumed.

All these months later, Lil wonders if she did the right thing by accepting a gift she knew she found suspect. She also is nagged by the thought that perhaps it wasn't entirely fair to her colleagues to offer them the banana bread when she had concerns about its origins.

"Should I have handled this differently?" Lil wonders.

Yes. Yes, Lil should have handled this differently.

There was nothing wrong with being gracious about accepting the gift when she knew she would never eat here. Many of us have received gifts over the years, food or other, where we knew on impact there was no way we would use it, display it, or consume it. But there's no need to embarrass a gift giver by refusing their gift or questioning their taste. Expressing thanks for a gift is appropriate and takes little effort.

Where Lil went wrong was to foist the suspect banana bread onto her colleagues without disclosing her concerns about its "cleanliness." If Lil was concerned and refused to eat it because it might have been prepared in an unclean setting, it was not OK to risk her colleagues' health by putting it out for their consumption -- and, given the history of shared food in her workplace, she was confident it would be consumed.

That no one got sick after eating the banana bread is a good thing, but doesn't make right the wrongness of Lil's choice. The right thing would have been for Lil to accept the gift and then, if she believed the banana bread was not fit for consumption to dispose of it when the gift giver was not present to witness its burial.

If Lil was unwilling to tell her colleagues about her concern about the cleanliness of the gift giver's kitchen because it might color their perception of the banana bread and its giver, then she should have taken that as a sign to toss it rather than share it. No one should put the health of colleagues at risk, even if the perception of that risk proves to be ill-founded.

Jeffrey L. Seglin, author of The Simple Art of Business Etiquette: How to Rise to the Top by Playing Nice, is a lecturer in public policy and director of the communications program at Harvard's Kennedy School. He is also the administrator of www.jeffreyseglin.com, a blog focused on ethical issues.

Do you have ethical questions that you need answered? Send them to rightthing@comcast.net.

F ollow him on Twitter: @jseglin

(c) 2015 JEFFREY L. SEGLIN. DISTRIBUTED BY TRIBUNE CONTENT AGENCY, LLC.

Published on September 18, 2016 09:34

September 11, 2016

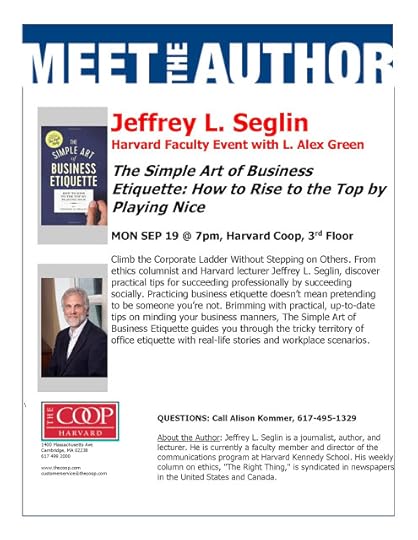

Harvard Coop Event, Monday, September 19, 2016

If you find yourself in Harvard Square in Cambridge, on Monday, September 19, at 7 p.m., please join me and Alex Green for a Q+A about

The Simpler Art of Business Etiquette.

If you find yourself in Harvard Square in Cambridge, on Monday, September 19, at 7 p.m., please join me and Alex Green for a Q+A about

The Simpler Art of Business Etiquette.

Just show up or sign up for the event on the Harvard Coop's Facebook page here.

Published on September 11, 2016 06:55

Why won't assisted living facility enforce its no-gifts policy to employees?

A reader wonders how "big of a stink" she should make about something going on in the assisted living facility where her mother lives.

The director of the facility told her there is a "very strict policy" against residents giving gifts of any sort to employees. "If offered," she says the director told her, "the employees will refuse the gift." The problem is that the policy is not being enforced.

While her mother has thrived at the facility compared to how she was doing in her own home, her daughter says her mother likes to give "little gifts" to her aides, such as fruit, soda, candy, and trinkets she buys at the local dollar store. Occasionally, the gifts are more expensive and include earrings or bracelets she buys from visiting vendors. "She also buys many, many baby gifts when one of the employees has a new baby, which seems is often," she says.

While her daughter thinks such gift giving is harmless and it makes her mother happy, "not once has an employee refused a gift even though supposedly it is against policy."

What concerns her daughter the most, however, is that her mother recently has started giving away some personal items that she had when she lived in her own home. Her daughter is worried that her mother's decision to give away personal items could be a warning sign that her judgment is fading, and that employees are taking advantage. When she asks her mother about the items, she tells her daughter that "she alone has the right to give whatever she wants to whoever she wants."

In the past when she has confronted the director of the facility about these gifts, he's been dismissive, saying that her mother "probably lost whatever it was that she gave away, since workers seem to deny receiving gifts."

Now, she believes she needs to bring the issue up with the director again. If he does not adequately address the breach of policy, she asks if she should contact an ombudsman for the company that owns the facility.

"My mom loves living there, and would not want to move," she writes. "Maybe my mom is truly competent and should be allowed to make gift giving decisions for herself. Maybe I should do nothing. What, if anything, is the right thing for me to do?"

My reader's mother is correct in stating that, as long as she is competent, she should be allowed to make her own gift-giving decisions. But it's wrong for the employees to be accepting gifts if there is indeed a strict policy against them receiving gifts of any sort from residents. For this rule to be effective, it must be enforced by the director and observed by all employees. If the director dismisses complaints about gifts that were accepted, then he is sending a message to employees that violating the rule has no consequences.

The right thing is for the daughter to meet with the director again. If he brushes off the daughter's concerns, she should let him know that she plans to report the issue to the company's ombudsman.

The rule should be enforced. Even if residents desire to give gifts to employees now, enforcing the policy helps ensure that residents are not taken advantage of later.

Jeffrey L. Seglin, author of The Simple Art of Business Etiquette: How to Rise to the Top by Playing Nice, is a lecturer in public policy and director of the communications program at Harvard's Kennedy School. He is also the administrator of www.jeffreyseglin.com, a blog focused on ethical issues.

Do you have ethical questions that you need answered? Send them to rightthing@comcast.net.

F ollow him on Twitter: @jseglin

(c) 2015 JEFFREY L. SEGLIN. DISTRIBUTED BY TRIBUNE CONTENT AGENCY, LLC.

Published on September 11, 2016 06:45

September 4, 2016

Should therapist use client to gather information on someone else?

A psychotherapist was referred a client by a former colleague. The client, a friend of the former colleague, was looking for a therapist who could help her sort through some issues. Over the course of several months of meeting the psychotherapist and client built a strong rapport by focusing on the client's issues.

The psychotherapist learned during those months that the former colleague was having some health issues. She tried to contact her former colleague with no success. Growing concerned, she asked other mutual colleagues if they had heard directly from the former colleague. None had.

Now, the psychotherapist wonders how appropriate it might be to ask the client in passing how the former colleague is doing. I suspect the psychotherapist knows the answer to her question, but asks it anyway out of concern for the former colleague.

While most licensed therapists have some sort of professional code of conduct to which they adhere, I'm not sure that the code would specifically address the psychotherapist's question she asks here.

What the psychotherapist should remember, and, again, I suspect she does, is that her relationship with her client is built on one that focuses on the client's needs, not on the psychotherapist's or on her former colleague's. By asking the client how the psychotherapist's former client is doing, she shifts the focus of their relationship away from the client's needs and onto her own. Granted, psychotherapists are only human and have needs too, but in the therapeutic relationship, the right focus seems like it should be on the client's needs.

The right thing would be to refrain from asking the client about the former colleague's condition.

Given that the client had a pre-existing relationship with the former colleague and was her good friend, however, there's a chance that the client herself might bring up the former colleague -- particularly since the client knows the psychotherapist also had a pre-existing relationship with the former colleague. If this happens, then the right thing is for the psychotherapist to let the client talk and to engage her in a discussion about the former colleague in a way that stays focused on the client's needs.

The psychotherapist's concern about her former colleague comes from a place of concern and compassion. Her intentions about wanting to know how she is are good. But she should not let her compassion for her former colleague interfere with the work she is doing with her client.

If the psychotherapist is truly concerned about the former colleague's well-being, she should figure out a way to check in on her without violating the trusting relationship she has built with her client. But at some point, if the former colleague doesn't respond to calls or emails, the psychotherapist might want to take that as a sign that the former colleague is not prepared to discuss whatever it is that is going on. The psychotherapist might want to be prepared to let things lie until the former colleague is ready to respond.

The psychotherapist is better trained than I am to entertain what might be motivating the former colleague not to respond. But she should honor the boundaries she's built with her client and those that the former colleague establishes.

Jeffrey L. Seglin, author of The Simple Art of Business Etiquette: How to Rise to the Top by Playing Nice, is a lecturer in public policy and director of the communications program at Harvard's Kennedy School. He is also the administrator of www.jeffreyseglin.com, a blog focused on ethical issues.

Do you have ethical questions that you need answered? Send them to rightthing@comcast.net.

F ollow him on Twitter: @jseglin

(c) 2015 JEFFREY L. SEGLIN. DISTRIBUTED BY TRIBUNE CONTENT AGENCY, LLC.

Published on September 04, 2016 05:40

August 28, 2016

Does reader need to correct oversight at the airport?

After a couple of weeks on vacation in Europe, E.W., a reader from Massachusetts, was ready to return home. He got a car to the airport and made his way through security with plenty of time to spare before his flight took off. He'd hoped to spend a few of the remaining Euros he had on gifts for friends and family back home.

In addition to a few souvenirs and several boxes of Toblerone chocolate, E.W. bought a small bottle of liquor for a neighbor who was having a party a few days after E.W. got home. At the register, the cashier asked for a copy of E.W.'s boarding pass each time he made a purchase. She sealed up the bottle of liquor in a plastic bag that she then placed in another shopping bag.

On the plane, the flight attendant passed out forms for U.S. citizens to fill out about their trip to indicate any purchases they were bringing back into the country. E.W. filled out the form and tucked it into his passport so he could give it to a U.S. Customs officer when he arrived in Massachusetts, after a long night's flight. He indicated on the form what he had purchased and how much he had spent.

Groggy from the flight and not yet adjusted to the time difference between where he'd been and where he was now, E.W. stepped up the Customs officer and presented his passport along with the form he'd filled out on the plane. The Customs officer looked E.W. over, looked his passport over, and then asked a few questions, including, "Did you purchase any liquor?"

While he'd indicated on his forms that he'd made purchases, E.W. answered "no" without thinking anything about it. The Customs officer stamped his passport and sent E.W. on his way. It was only as he was board a bus home that E.W. realized he was indeed carrying in his backpack a small bottle of liquor he'd purchased.

Now, E.W. wonders if he's in trouble because he answered incorrectly. "Should I do something to correct my error?" he asks.

I'm not a lawyer and have no expertise in Customs law, but it wasn't right to answer the Customs officer incorrectly and I suspect there can be significant penalties for doing so. But E.W. had indicated his purchases on his forms so he clearly wasn't trying to hide anything. If the Customs officer had asked to check E.W.'s backpack, I suspect the request would have awoken his memory about the small bottle residing there. According to U.S. Customs and Border Protection's website, the U.S. permits its citizens to bring a bottle of wine or liquor home without incurring any duty or tax, so E.W. was not violating any laws by bringing the bottle into the country. (Canada's Border Services Agency has a similar provision for its citizens.)

The right thing would have been to tell the Customs officer about the purchase. But as long as he indicated the purchase on his form, now that he is home, it doesn't seem necessary for E.W. to call U.S. Customs to come clean. I suspect it's a mistake he will never make again.

Jeffrey L. Seglin, author of The Simple Art of Business Etiquette: How to Rise to the Top by Playing Nice, is a lecturer in public policy and director of the communications program at Harvard's Kennedy School. He is also the administrator of www.jeffreyseglin.com, a blog focused on ethical issues.

Do you have ethical questions that you need answered? Send them to rightthing@comcast.net.

F ollow him on Twitter: @jseglin

(c) 2015 JEFFREY L. SEGLIN. DISTRIBUTED BY TRIBUNE CONTENT AGENCY, LLC.

Published on August 28, 2016 05:47

August 21, 2016

Make sure you know where your email is going

How obligated are we to let people know when they've emailed you by mistake?

As he was walking home from work, J.L. came to a stoplight. He decided to check his smartphone for email while he was waiting. As he scrolled through, J.L. noticed that he'd been copied on an email that a distant cousin of his had written to her daughter.

"Should we invite [J.L.] to your wedding," the cousin asked her daughter. "He and his wife were very nice to us when we visited."

J.L. was certain that the email wasn't intended for him and he thought he would let it pass. But when he got home, he checked his email again and there among his email thread was a response from his cousin's daughter:

"If we invite him, do we need to invite his sister, too?"

J.L. thought the discussion was beginning to sound like they wanted to think about inviting him, but weren't crazy about the idea of inviting his sister. He remained convinced that his cousin and her daughter had copied him in error, but even in the replies, his name stayed on the routing list.

Before, when there was one email, he was fine just letting it pass and not alerting his cousin. But now that the discussion seemed like it might turn to one that included a more personal tone of who they might not want to invite to the wedding and why, J.L. believed it might be best to say something to his cousin.

He'd only met his cousin's daughter once when she was very young, so he had no expectations of being invited to her wedding. Since it was in a city different from the one in which he lived, he wasn't crazy about the idea of having to book a flight and hotel for the event anyway. Would alerting his cousin make her feel like they definitely should invite him now that he knows they were thinking about it?

J.L.'s predicament is yet another reason for each of us to be far more careful about what we send out in email and to whom we send it. There are many stories of employees hitting "reply all" to a received email and sending a snarky message that offends someone on the receiving end that the snark sender didn't even realize was on the recipient list.

J.L. is not obligated to alert his cousin that she inadvertently copied him on an email. She did not inadvertently disclose personal information that could do her or her daughter damage. Still, copying J.L. on an email in which they discuss whether he or his sister makes the wedding list cut could prove embarrassing to his cousin.

Given that the email discussion continued past the first errant message, the right thing for J.L. to do is to let his cousin know that she mistakenly copied him. If he wants to he can add a note about how kind it was for them to consider inviting him, but that given he didn't know the daughter all that well, he had no expectations of being invited. The right thing for the cousin and her daughter (and you too) to do is to take the time to make sure you're sending the email you want to send to the people you want to send it to.

Jeffrey L. Seglin, author of The Simple Art of Business Etiquette: How to Rise to the Top by Playing Nice, is a lecturer in public policy and director of the communications program at Harvard's Kennedy School. He is also the administrator of www.jeffreyseglin.com, a blog focused on ethical issues.

Do you have ethical questions that you need answered? Send them to rightthing@comcast.net.

F ollow him on Twitter: @jseglin

(c) 2015 JEFFREY L. SEGLIN. DISTRIBUTED BY TRIBUNE CONTENT AGENCY, LLC.

Published on August 21, 2016 05:36