Jim C. Hines's Blog, page 142

July 13, 2012

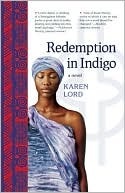

Redemption in Indigo, by Karen Lord

Karen Lord is one of this year’s nominees for the Campbell Award for Best New Writer. I interviewed her here earlier this year. Having read Redemption in Indigo [Amazon | B&N | Mysterious Galaxy], I can see why she’s on the ballot.

Karen Lord is one of this year’s nominees for the Campbell Award for Best New Writer. I interviewed her here earlier this year. Having read Redemption in Indigo [Amazon | B&N | Mysterious Galaxy], I can see why she’s on the ballot.

The official description:

Karen Lord’s debut novel is an intricately woven tale of adventure, magic, and the power of the human spirit. Paama’s husband is a fool and a glutton. Bad enough that he followed her to her parents’ home in the village of Makendha—now he’s disgraced himself by murdering livestock and stealing corn. When Paama leaves him for good, she attracts the attention of the undying ones—the djombi—who present her with a gift: the Chaos Stick, which allows her to manipulate the subtle forces of the world. Unfortunately, a wrathful djombi with indigo skin believes this power should be his and his alone.

Lord mentions that chapters two through four are loosely based on a Senegalese folk tale, and the entire book has that same feel. From the very first page, Lord creates the illusion not of turning the pages, but of sitting back and listening to a master storyteller, one who has no compunctions about addressing the audience directly. It’s a voice that works perfectly for Paama’s story.

I loved this book, and to be honest, I’m having a hard time figuring out what to say about it, beyond the fact that Lord consistently made choices in her storytelling that I didn’t expect, but that felt right when I read them. None moreso than the way she ended things, which I can’t talk about without spoiling the whole darn book. Sigh.

I will say that if you’re looking for a traditional Western/American fantasy about an orphaned farmboy who vanquishes the evil overlord with a magic doohickamabob, this isn’t the book for you. Lord’s story challenges such tropes from page one, questioning everything from the nature of evil to the assumption that the only heroic choice is to fight and defeat your presumed foes.

One of my favorite moments in the book is when the djombi threatens to harm Paama’s family unless she returns the Chaos Stick … so she immediately hands it over. It’s instinctive. She doesn’t crave power, and she refuses to risk her loved ones over some ridiculous need to maintain face or appear defiant.

And of course, topping everything off, there’s a trickster spider character. How can I not love the trickster spider?

Let me put it this way. I read most of this one in the airport on the way to Kentucky, and I was happy my flight was delayed, because it meant I had more time to read.

Discussion is absolutely welcome, as always!

July 12, 2012

Goblin and Libriomancer Stuff

I’ve got two more book reviews coming, but I thought I’d break things up with a bit of self-promotion, starting with the goblin omnibus The Legend of Jig Dragonslayer [Amazon | B&N | Mysterious Galaxy], which came out just over a week ago. I was very excited to get my first look at the finished book at Fandom Fest. Thank you, Joseph-Beth Booksellers! It’s shiny and pretty (with a cover I like much better than the original design), and at 800+ pages, it means I’ve finally written a doorstopper book!

Sure, it takes three of my goblin novels to make one doorstop, but I’ll take what I can get

[image error]

When I got back from vacation, I found two boxes of author copies waiting for me. You can see Taz inspecting both shipments for damage.

HEY REVIEWERS: The fact that both of these books have now been printed means this might be a good time to contact DAW/Penguin for review copies, if you haven’t already received one. (If you need contact info, hit me up, but please understand that they don’t generally ship out books just for Amazon or Goodreads type reviews.)

Only 26 days until Libriomancer [Amazon | B&N | Mysterious Galaxy] comes out. I’ve seen a few reviews pop up on Goodreads, almost all positive so far, thanks to the giveaway Penguin held. Even better than that, getting my author copies early means I was able to deliver my very first copy of the book to some dear family friends. I’ve known them for 34 years, and from the very beginning, they always encouraged me to read and to explore the magic of books. So I dedicated this one to them, since Libriomancer seemed like the perfect book with which to thank them.

It’s one of the amazing things about being a writer. With every book and dedication, I can give someone a gift very few people ever get. It’s a wonderful feeling.

Michigan Mini-Tour: It’s not an official book tour, but I’ve got enough signings lined up that I’m calling it one. The week of August 7 when the book comes out, I’ll be in Lansing, Ann Arbor, Walker/Grand Rapids, and Kalamazoo. Details are on my website.

I feel like there was something else I wanted to mention … oh, right! I announced this on Twitter and Facebook, but not here. Graphic Audio will be doing audio book editions of all three goblin books. This is a company that does full-cast recordings with music and sound effects. They’ve done books by folks like Brandon Sanderson, Elizabeth Moon, Peter Brett, and many more. I’m really looking forward to seeing what they come up with. (I don’t know when it will be released or who they’ll be getting to do the different voices. They’ve already shot down my suggestion to get Samuel L. Jackson to play Jig.)

Yeah, it’s a rather hectic summer around these parts, but I’m enjoying it!

July 11, 2012

Hugo Novellas, Part 2

When I registered for Worldcon, my goal was to read/watch/listen to ALL THE THINGS on the Hugo Ballot, and to review them as well. It was a good goal. A noble goal. A goal which, with less than a month until the July 31 voting deadline, simply ain’t gonna happen.

That said, I did get some reading done over the past few weeks, starting with the rest of the nominated novellas. (I reviewed the first three here.) Remember that both attending and supporting memberships give you voting rights and access to the Hugo Voter Packet.

#

, by , really stuck with me. Doctor Evan Wei, a Chinese-American historian, develops a form of time-travel technology that allows an individual to observe the past, but not to change or interfere. The catch is that any given moment of history can be seen only once, after which the Bohm-Kirino particles that allow you to reconstruct that moment are gone forever.

, by , really stuck with me. Doctor Evan Wei, a Chinese-American historian, develops a form of time-travel technology that allows an individual to observe the past, but not to change or interfere. The catch is that any given moment of history can be seen only once, after which the Bohm-Kirino particles that allow you to reconstruct that moment are gone forever.

The story focuses on Unit 731, a Japanese biological and chemical research facility during World War II, in which thousands of people as many as 200,000 people, primarily Chinese and Korean prisoners, were killed in various experiments.1 Dr. Wei’s goal – and Liu’s as well – is to bring to light the atrocities that were committed, atrocities which have been suppressed and ignored.

Liu documents his sources, citing various texts, testimonies, articles, hearings, and other accounts to support his story. And while the story of Wei’s efforts and the political and personal backlash is a good one, in the end I think it’s overpowered by the history lesson.

The science was, I felt, the weakest part of the story. Liu provided just enough detail about time travel to make me question it, and to erode my suspension of disbelief. But from a thematic perspective, particularly when it comes to the danger of erasing history, I thought it worked well. “We cannot avert our eyes or plug up our ears. We must bear witness and speak for those who cannot speak. We have only one chance to get it right.”

The Man Who Bridged the Mist, by Kij Johnson, tells the story of Kit Meinem, an engineer and architect charged with building a bridge to connect the towns of Nearside and Farside. The river of mist that separates the towns is thick and dense enough to support boats, but it’s also home to dangerous fish-like creatures, some of which are enormous enough to destroy the ferries and their passengers.

The Man Who Bridged the Mist, by Kij Johnson, tells the story of Kit Meinem, an engineer and architect charged with building a bridge to connect the towns of Nearside and Farside. The river of mist that separates the towns is thick and dense enough to support boats, but it’s also home to dangerous fish-like creatures, some of which are enormous enough to destroy the ferries and their passengers.

The mist is fascinating, but it’s never fully explored or explained, and that works. The story isn’t about big flashy battles or the magic of the fantastic; it’s about the magic of Meinem’s bridge, the long process of construction and the ways in which that bridge will change the world. It’s a story that shows the triumphs and the costs of progress. Some of the costs are obvious, like the deaths among Meinem’s crew.

Others are subtler. Rasali Ferry is skilled at crossing the mist. She knows the dangers, but the mist is where she feels at home and at peace. Meinem’s bridge will put an end to her way of life, a fact she struggles to accept throughout the course of the story.

I liked this one as much for what it wasn’t as for what it was. Instead of big magic and effects, Johnson gives us Meinem’s love of engineering, his passion for his work, and the lovingly detailed process of building the bridge and changing the world. (And as a writer, I can’t help thinking about the bridge as a metaphor for stories.)

[image error]The Ice Owl, by Carolyn Ives Gilman, is the most traditional story of the three. The city of Glory to God is described as a city of rust, a city of religious rule and corruption. In the opening pages, the Incorruptibles – the “army of righteousness” – enter the Waster enclave where Thorn lives and burn down a school. Thorn sets out and finds a tutor, a historian called Magister Pregaldin who turns out to be far more than just a teacher.

I liked a lot of the worldbuilding and ideas in this one. Lightbeam travel means Thorn is 145 years old, at least by sequential time, due to time spent in transit. The titular ice owl is fascinating and symbolic and tragic, the last of its kind, hibernating in Pregaldin’s freezer.

Underlying the events of the story is the Holocide, a SFnal parallel to the Holocaust. Pregaldin deals in looted and lost artwork from that time. Thorn’s mother is seeing a man named Hunter, who pursues war criminals from the Holocide. As Thorn begins to suspect her tutor of being connected to the Holocide, she sets out to learn what role he played both then and now.

For some reason, this story didn’t quite come together for me as well as the others. I liked Thorn’s character: she’s smart, impulsive, and determined. I liked her investigation into Pregaldin’s past. I liked her family conflicts, her frustration with being the responsible one for her mother. But while there were a lot of great pieces, there were times they still felt like pieces instead of all fitting into the larger story. I’ve seen some very positive reviews of this one, so it might be a matter of taste, or maybe I just didn’t read it carefully enough.

#

So there you have it, the rest of the novellas. For those of you who’ve read them, what did you think?

—

Ken emailed me to clarify that the number of prisoners killed in Unit 731 is unclear, but estimates are in the thousands. The 200,000 number is the lower estimate of people killed by biological weapons developed in Unit 731. My apologies for my mistake. ↩

July 10, 2012

To The Woman Who Groped Me at FandomFest

I suppose it was my own fault.

I considered it a kindness to ignore you as you whined about how drunk you were and preemptively apologized to anyone you might puke on. As you leaned on your friend and began to swear at people for having the audacity to stop you from reaching your floor, as if they somehow believed they had a right to use the elevator too.

It was my fault for tuning you out as your verbal diarrhea grew even nastier. For not realizing when your mumbled “fuck it!” devolved into “faggot,” a slur you apparently directed at anyone getting off of the elevator. Including me.

It’s my fault for not catching what you were spewing until I was squeezing toward the doors, at which point you apparently took my annoyance as reason to announce my gayness to the world and grab my ass.

My fault for those few seconds of what-the-hell-just-happened shock, during which time the elevator doors closed, robbing me of any chance to respond.

There are many things I could have said and done, had I reacted faster. I could have shouted, “What the hell is wrong with you?” I could have called you out on your bigotry. I could have responded physically, taking your wrist and refusing to give it back until you apologized. I could have snapped a picture or jotted down your badge name and reported you to security.

I didn’t do any of those things. I don’t know your name. I couldn’t tell security what you looked like. Given how wasted you were, I don’t know if you even remember what you did.

Of course, the thing is, it’s not my fault. I’m not the one who decided to grope a stranger in an elevator as some sort of petty, drunken game. I’m not the friend who stood by and did nothing while it happened.

To be fair, I don’t know what happened after those elevator doors closed. It’s possible your friend told you exactly how much of an asshole you were being, but nothing I observed up to that point makes me think anything happened, aside from maybe a little nervous laughter.

In the silver lining department, it was … educational. I have a better understanding of the self-blame; of the way people replay the situation again and again, imagining what you could have done differently; of some of the ways others respond when you talk about it, the jokes and the advice about what you should have done, all offered with love and the best of intentions.

One person commented, “Welcome to the world of women.” While it’s not just women who get treated this way – I was talking to another author this weekend about his experience with a woman who refused to respect the word “no” – it’s certainly far more common for men to target and harass women.

And you know what? It’s bullshit. It’s harassment, and it’s assault.

We focus on what the victims should do. How they should fight back and report it and take responsibility for making sure the other person doesn’t do this to anyone else.

I don’t need to be told what I should have done. Believe me, I played that scenario out again and again in my head, and I guarantee I’ve already come up with pretty much every possibility you’re going to suggest.

None of which helps.

A part of me wants to insist it wasn’t a big deal. I was never in physical danger. It was only a second or two of physical/sexual contact. But it was unwanted sexual contact. It was, however brief, a deliberate violation. And it is a big deal.

I had to keep reminding myself, even though I knew it, that it’s not my fault. That the responsibility belongs with the bigoted asshole who did this. I don’t care that she was drunk. If you’re the kind of person who does this shit when you get drunk, then you’ve forfeited the right to get drunk around people. Because alcohol doesn’t excuse it or make it okay, and if you can’t control yourself when you’re drunk, then you damn well need to stay sober.

And if you’ve watched a friend pull this kind of shit and said nothing – if you stood there and let it happen, and didn’t confront them afterward – then you’re also part of the problem. Because silence speaks too, and your silence tells your friend that his or her behavior is okay. That you’re cool with them harassing people.

Overall, I had a great time at FandomFest, but this pissed me off. It pissed me off that it happens, and it pisses me off that it keeps happening.

July 9, 2012

Morgan Keyes: Writers Write (And Do A Lot Of Other Things)

Morgan Keyes is the author of the forthcoming middle-grade novel Darkbeast [Amazon | B&N | Mysterious Galaxy], which just sounds cool. Check out this setup from the description:

In Keara’s world, every child has a darkbeast—a creature that takes dark deeds and emotions like anger, pride, and rebellion. Keara’s darkbeast is Caw, a raven. Caw is her constant companion, and they are magically bound to each other until Keara’s 12th birthday. For on that day Keara must kill her darkbeast—that is the law. Refusing to kill a darkbeast is an offense to the gods, and such heresy is harshly punished by the feared Inquisitors.

I like this setup, and having read a little of Keyes’ stuff under her other name, I’m adding Darkbeast to my evergrowing wish list…

#

It’s become a cliche: Writers write. If we want to produce a novel, we need to put our butts in our chairs, our hands on our keyboards, and write.

Most people expand that hoary advice a bit: Writers read. If we want to know what’s going on in “our” genres, we need to read, early and often. We even need to read outside our genres, to get an idea of potential broader markets of readers, and to keep abreast of developing trends that might influence our own specific fields.

I’ve only recently realized how many other things that writers need to do.

A couple of months ago, I put the finishing touches on DARKBEAST, a middle grade fantasy novel that will be coming out at the end of August under the pen name Morgan Keyes. To get the book completely “put to bed” I spent months living the story, breathing its details, dreaming its myriad plots and twists. When I turned in the very last, absolutely-final, not-going-to-change-a-word edits, I found myself rather … empty.

A couple of months ago, I put the finishing touches on DARKBEAST, a middle grade fantasy novel that will be coming out at the end of August under the pen name Morgan Keyes. To get the book completely “put to bed” I spent months living the story, breathing its details, dreaming its myriad plots and twists. When I turned in the very last, absolutely-final, not-going-to-change-a-word edits, I found myself rather … empty.

I tried to sketch out story ideas, but nothing seemed fresh. I thought about branching out into new genres, but I felt utterly unprepared. I read background books for one new novel, researching a beloved public domain work that I intended to update as a modern story, only to realize (after a month of writing and several false starts) that the 19th century sentiment in that novel could not be translated into the sort of sassy, contemporary book I wanted to write.

In short, my creative well was empty.

And then, I attended the Silverdocs Documentary Film Festival. The festival included 114 films aired over seven days. I saw a fraction of them, “only” nineteen. They varied widely in style. One was as short as four minutes; several came in at right around two hours. They covered topics as varied as the manufacture of fortune cookies to the rock band Journey to migratory birds in Central Park.

And here’s the thing: each of those movies told a story. Each displayed unique characters in a specific setting solving carefully-defined problems. The documentaries were little gems of narrative. If they’d been books, they would have fallen into the genre of “creative non-fiction”, the novelistic exploration of narrow non-fiction topics, like Simon Garfield’s MAUVE, HOW ONE MAN INVENTED A COLOR THAT CHANGED THE WORLD or Trevor Corson’s THE SECRET LIFE OF LOBSTERS.

In fact, the documentaries weren’t merely lenses on another world. They were prisms. They shattered my preconceived notions, breaking my ideas into multiple component parts. After every movie, I engaged in long discussions about what the facts were, what they meant, how the filmmaker relayed them.

And somewhere along the way, I started to think of stories I wanted to tell. I began to imagine different types of narratives, building on the traditions of the fantasy genre that has long been my literary home, but different. I scribbled down notes for one story, and then another, and then another.

Viewing stories in a different medium than the one in which I regularly create allowed my “art” brain to relax. The films allowed the creative part of me to re-awaken, to begin exploring new boundaries.

Writers write. Writers read. And writers experience art wherever they can find it, in whatever format is available in the instant.

Do you agree? Disagree? If you’re a writer, have you found inspiration in other media? If you’re a reader, have you read works that were clearly inspired by other media?

July 8, 2012

Marie Brennan: Folktales and Legends

I’ve reviewed a number of Marie Brennan’s (Twitter, LJ) books, including her Onyx Court series (gorgeous historical fairy fantasy set in London). Her next book, A Natural History of Dragons [Amazon | B&N | Mysterious Galaxy], is currently sitting on my TBR pile, because I’m luckier than you are. I’ve been rushing to prepare all of these guest posts, and my brain is getting fuzzy, so I’ll just conclude by saying Marie invented the left parenthese, is a third degree black-belt in a rare style of piccolo-based karate, and is composed of 62% dark matter.

I’ve reviewed a number of Marie Brennan’s (Twitter, LJ) books, including her Onyx Court series (gorgeous historical fairy fantasy set in London). Her next book, A Natural History of Dragons [Amazon | B&N | Mysterious Galaxy], is currently sitting on my TBR pile, because I’m luckier than you are. I’ve been rushing to prepare all of these guest posts, and my brain is getting fuzzy, so I’ll just conclude by saying Marie invented the left parenthese, is a third degree black-belt in a rare style of piccolo-based karate, and is composed of 62% dark matter.

#

Hello again, everyone! Did you miss me? (Don’t answer that.)

Last time I guest-blogged for Jim, on the topic of fairy tales and how they make no sense, I made a passing comment about how modern fantasy is more often like the folklore category of “legends” than it is like the Brothers Grimm. Several people expressed interest in hearing me expand on that thought, so here I am, back for a second round.

When I talk about the aesthetic qualities that distinguish folktales from legends — and let me digress briefly to say that I’ll be talking about “folktales” rather than “fairy tales” because most things in that category don’t actually have fairies in them — I’m mostly drawing on an influential book by Max Lüthi called The European Folktale: Form and Nature. As the title gives away, it focuses on European sources; what folktales are like in other regions of the world, and whether or not it makes sense to have a general category of “folktale” that you apply to all cultures, are questions that could fill not only a blog post but an entire grad school course. But since modern fantasy rests firmly on a foundation of European material, and is still only gradually opening up to other paradigms, his work is a good place to start.

I’m going to cheat here and quote myself directly, from a paper I presented at a conference and later turned into an article for Strange Horizons: “Lüthi gives a number of descriptors for the folktale style, including one-dimensionality, depthlessness, abstract style, isolation and universal interconnection, sublimation and all-inclusiveness.” You can go read that article if you want further explication of the latter points (I use them to analyze Meredith Ann Pierce’s novel The Darkangel, which is much more folktale-ish than most fantasy these days), but the main thing I want to unpack here is what Lüthi calls “one-dimensionality.”

In a folktale, things take place in “a land far, far away” — a land that is, furthermore, usually nameless. By contrast, in a legend the action often occurs in a named location, and one that is known. It isn’t just “the dark forest;” it’s that forest on the other side of the river from the village where the tale is being told. Legends are frequently bound into the landscape of the teller: this hill, that rock, the lone oak tree where your horse threw you last week. They’re about the world the audience lives in, and they are concrete.

The flip side of this, and the other component of what Lüthi means by “one-dimensionality,” is that in a folktale, while things may be physically distant, they’re spiritually close. In fact, physical distance replaces spiritual distance. A folktale hero, wandering along in his journey, comes to the foot of a glass mountain. How much time does he spend goggling at the sight? None at all. The same goes for talking lions, huts on chicken legs, and walnuts with whole dresses crammed inside of them. Weird things aren’t weird, in folktales. Nor are they scary. They just are, and the hero doesn’t bat an eyelash at them.

Legends? Are scary. And weird. And the characters in them react appropriately. If a guy comes riding along with his severed head under his arm, the hero not only bats an eyelash, but runs for the hills. Things in legends are physically close, but spiritually distant.

By now you can probably see where I’m going with this. Sure, fantasy novels of the non-urban or non-historical sort don’t take place in our backyards (and even some of the urban ones take place in Generic City #12) — but their locations are specific. In fact, our genre prides itself on its ability to make up worlds that feel real, complete with place-names and maps and histories and politics and all the rest of it. Even when we’re rewriting folktale plots, our settings are rarely vague, nameless kingdoms. And when our characters encounter weird stuff? We not only want them to marvel, we criticize the author for bad writing if they don’t. There are types of fantasy that shoot for a different target — especially in short stories, where it’s easier to sustain an artistic “folktale” style; keeping it up for the length of a novel is hard — but as a publishing category, fantasy is dominated by works that mimic the qualities of legends.

Mind you, we still do steal a few of our tricks from folktales. Lüthi argues that one of the characteristics of the style is that objects in it often default to precious metals and minerals, and a limited range of color. Gold and silver, black and white and red and sometimes blue . . . we use green more than folktales do, for which we can probably thank Tolkien and his trees, but it’s true that lots of things fall into that narrow range of shades. And we certainly do love extremes, where our protagonists are orphans or youngest children, royalty or peasants, but rarely middle children or middle-class. We’ve changed that some in recent years, but read through The European Folktale and you’ll see a few trends you might recognize.

Ultimately, of course, modern fantasy is its own thing, neither fish nor fowl, neither folktale nor legend. We’ve stolen tropes from myths and chivalric romances and a bunch of other genres both literary and oral. But if I had to pick one to say is the closest match, I’d probably pick legends.

July 7, 2012

E. C. Ambrose: Camoflauging Your Soapbox

E. C. Ambrose (Twitter) is the author of a new dark historical fantasy series about a medieval barber surgeon, which starts next year from DAW books. The first book, Elisha Barber, is scheduled for a July 2013 release. E. C. blogs about history, fantasy and writing at www.wordpress.com/ecambrose and spends too much time in a tiny office in New England with a mournful black lab lurking under the desk.

#

Camouflaging your Soapbox: Writing for the Cause

One of the reasons we write is to find ways to explore or express ideas about the Big Things—science, religion, ethics, choices. And writing speculative fiction affords the opportunity to design thought experiments about subjects that can never be undertaken in a lab. We can create entire worlds, cultures and histories to push a question to the limits: What if. . .? and fill in the blank with a twist on a subject we’ve been brooding over, something we’re passionate about, something that courts controversy and stirs up readers. That’s the kind of book that gets people talking and thinking. And sometimes, gets the writer in trouble.

How often have you heard a reader complain about an author (frequently a big name, lightly edited author) using a book to expound upon some cause near to the author’s heart? Often, the cause is religious or political, sometimes social or ethical. It’s one thing to be inspired by a real-life hot button issue, and quite another to deliver a diatribe about it in the form of a novel. Nobody likes to be lectured, especially when they’ve picked up your book in search of entertainment.

So what if you do have a cause? You have a point of view on an issue. You want to explore it, to support it or to attack the other side. You could simply keep it on your blog and confront the issue directly. You could also put together a theme anthology where profits will support the cause. In my case, I’m donating some of the profit from my books to raise awareness and combat human rights abuses, and torture in particular. My series has a medieval setting, but when I started researching torture, expecting to learn more about the rack, the wheel, and other such arcane devices, I was horrified to find how much of the information was not medieval at all, but came from contemporary accounts. Little of this research made it into the books, but this realization informed my approach to writing them.

Fiction is a powerful vehicle for social inquiry and for social change (see the lasting impact of books like Uncle Tom’s Cabin, or Black Beauty). The strongest themes are those that the reader discovers without realizing it, those that arise from the conflicts of sympathetic and believable characters engaged in the pursuit of their own goals—not your goals as an author or as a person. Allow your characters and their conflicts to embody different aspects of the cause—don’t tell them, or the reader, what to think, but rather, give them a stage broad enough to create real drama. Embed the reader in the experience of the character to show them the problems you see.

It helps to present multiple points of view on the subject, and to ensure (at the very least) that not everyone on the other side of the question is simply evil. This is a common failing of the cause-driven author, though it is also an attribute of a number of best-sellers. In Hit Lit, a recent book analyzing a dozen blockbusters of the last 100 years, James Hall found that many of them had religious themes, and that these themes were often one-sided, or at the very least, presented from the perspective of a skeptic. It’s an approach that engages both habitual readers and also those who read only a handful of books but want to see what all the fuss is about. There’s a fine line between stoking a lively conversation, and setting off an explosion. Most authors would love to achieve Dan Brown status, but it would be nice to get there without also getting death threats.

I believe that fiction can be a force for change, for confronting the causes we feel strongly about—but it works best when we’re using the tools of the novelist—character, conflict, plot—to challenge readers to experience that cause from the inside out.

And if an author is just looking to lecture? That’s what blogs are for.

July 6, 2012

Steven Harper Piziks on Homelessness

Steven Harper Piziks (Twitter, LJ, Facebook) is one of the first Michigan authors I remember meeting back when I started to take this writing thing more seriously. His most recent books are The Doomsday Vault [Amazon | B&N | Mysterious Galaxy] and The Impossible Cube [Amazon | B&N | Mysterious Galaxy]. Steven’s oldest son recently became homeless. I can’t imagine what he and his family are going through right now. He talks here about his experiences, about how his son Sasha opened his eyes to the problem of homelessness, and the things Steven is doing to try to raise money and awareness for people like his son.

#

I’ve mentioned elsewhere (http://spiziks.livejournal.com/370953.html) that my son Sasha is homeless. The reasons are difficult and terrible, and the short version is that it’s the least worst of all choices.

Last winter he spent his days on the street and his nights in a series of church basements. I worried about him constantly. He got robbed at knife point once. Another time he got caught outside when the church closed its doors for the night and he had to spend a winter night outdoors. It isn’t something I ever envisioned for the little boy I adopted seven years ago from Ukraine.

After several months, Sasha managed to get a bed at the Delonis Shelter in downtown Ann Arbor. He’s working on his GED and trying to find a job. It isn’t easy, however, for a 19-year-old to find work without a high school diploma.

I do see him from time to time. It’s a surreal version of a dad visiting his son at college. I drive down to Ann Arbor, pick him up at a warped version of a dormitory, and take him to lunch somewhere. We talk, I ask him if he needs anything like shoes or a trip to the laundromat, I slip him $20, give him a hug, and drop him off at the dorm again. Except it isn’t a dorm, and he isn’t heading back inside to finish a paper for Monday class.

Sasha once gave me a tour of Ann Arbor from the homeless point of view. We were strolling around downtown, and this is how it went:

“He’s homeless,” Sasha said, pointing at a man in a polo shirt and baseball cap as we strolled past the bus station. “And so is he, and him.” This at two more men, both clean-shaven, in jeans and work shirts. They looked like two guys heading home after their morning shift.

“Later I have to go down to the dorms,” Sasha said in his accented English. “This is the good time of year for finding stuff. The University [of Michigan] students are all moving out, and they throw things away. A friend of mine found a laptop in the trash piles. Worked fine. You can get good furniture–desks, chairs. But we have nowhere to put them, so we leave them. And food! The students throw out all kinds of food everywhere. Cans and bottles and milk and peanut butter and Ramen noodles. All good, all to eat. Walk behind the dorms and you find anything you want. They waste everything, and we have nothing here. I don’t understand it.”

“She’s homeless,” he continued, and pointed at a teenaged girl in a hoodie with a purse. “She’s seventeen and she ran away from home. I don’t know why.” He nodded at a woman with stringy gray hair. She wore a brown sweater despite the warm spring day. Smoke trailed from her cigarette. “She’s forty and homeless and pregnant. Her boyfriend lived in a hotel until they kicked him out because he had no money for the rent.”

“I don’t take the food,” he said. “Not if it’s open. I don’t think it’s good. And I don’t climb into dumpsters. Not yet. I am embarrassed to be seen doing that.”

A man with silver-streaked curly brown hair half strutted, half strolled across the street. He wore a suit jacket and slacks.

“I call him Peter Pan,” Sasha said. “He acts like he can fly. I worry he will get hit by car.”

We passed a row of restaurants and cafes.

“Some places will give you food at the end of the day,” Sasha said. “But you have to be there right when they close. Pizza places throw everything out, but I do not want to get it from the garbage, so sometimes I ask the girls at closing time, and they give some to me.”

“If you have a Bridge Card [food stamps], you can buy sandwiches or hot coffee from the grocery store, but there is no place to keep extra food at the shelter. So you can’t buy groceries, only expensive sandwiches.”

We passed an older man and a woman with backpacks and grocery bags. Sasha waved at them, and they waved back.

“I know them. They are going to Camp Take Notice,” he said.

Camp Take Notice, Sasha explained, is a strip of state-owned woodland on the outskirts of Ann Arbor. In the last few months, it’s become a shanty town of tents and ramshackle shelters for people with nowhere else to go. Its name is unofficial. The government, however, is now forcing the people off the land and building a fence around the land to keep them out. I blogged about that at the link above.

“Everyone looks at you funny if you have nowhere to live,” Sasha finished. “Like you aren’t a real person. It is hard.”

Every town has a homeless scene. I’ve become adept at spotting it now. Like a magician, Sasha has made the unseen fully visible to me. The restaurant where people come for food. The dumpster where people go to scavenge. The building where they go to sleep. The teenager/woman/man heading down the sidewalk, trying to look like they have somewhere to go.

Every town has a homeless scene. I’ve become adept at spotting it now. Like a magician, Sasha has made the unseen fully visible to me. The restaurant where people come for food. The dumpster where people go to scavenge. The building where they go to sleep. The teenager/woman/man heading down the sidewalk, trying to look like they have somewhere to go.

We can help. For the next year, I’m donating the royalties from my ebooks at Book View Café and Amazon to the Delonis Shelter. Every time you buy one, you’re making a donation. You can also donate to the shelter directly at their website. Equally good is to donate to your local organization or shelter for the homeless. Every dollar counts.

Together we can make the least worst a little better.

July 5, 2012

Alma Alexander: Writing the Other

Alma Alexander (Twitter, LJ) is a Pacific Northwest novelist, short story writer, and anthologist. Her books include “The Secrets of Jin Shei”, “Embers of Heaven”, “The Hidden Queen”, “Changer of Days”, the YA Worldweavers series, and “2012: Midnight at Spanish Gardens”; short stories have appeared in a number of recent anthologies, and “River”, the first anthology where she wore an editor’s hat, is out now.

The novel “Embers of Heaven” is now available in the USA for the first time – initially as an ebook at Amazon and at Smashwords, with a paperback edition to follow soon

#

Almost exactly a year ago, novelist Kari Sperring wrote a blog entry entitled “Other people’s toes.” You can go and read the full entry, but there are a few things I would like to pull out of there – to wit -

[on Connie Willis on Blackout/All Clear]

… the historical errors in them are, frankly, parlous, and — as an Oxbridge historian — I am personally rather offended by how stupid she thinks my kind are, apparently… Then I read [Connie Willis’s] short piece in the Bulletin. Here’s the key excerpt. ‘That era [Britain in WW2] is just so fascinating — the blackout, the gas masks, the kids being sent off to who-knows-where, old men and middle aged women suddenly finding themselves in uniform and in danger, tube shelters and Ultra and Dunkirk, and running through it all, the threat of German tanks rolling down Piccadilly! What’s not to like.’

That was when I looked up, and said, very sharply, ‘How about all the dead civilians? That’s not to like at all.’Because, you know, the Blitz was *not* fun.

Here’s my point. History is not a theme park. It’s not a story, either. It’s people’s real lives. If you’re going to write about it, about any part of it, you need to do your homework properly, you need to be respectful, because — as Ms Willis did with me — otherwise, you’re going to find someone’s sore place, someone’s vulnerability, someone’s sacred or difficult or secret thing, and you’re going to do damage. Other countries aren’t theme parks, either, nor museums, nor big bags of useful resources. They’re homes to millions, they’re people’s lives, too.

But the Blitz is not likeable, it’s not fun, it’s not an adventure playground. And talking about is as if it is lessens us all.

I guess what I’m saying is, at bottom, very simple. Be careful, when you talk about other people’s things, histories, homes. We don’t all understand the same things in what we read, we don’t all have the same assumptions. We start from different places. It’s far too easy to discount, to elide, to erase people by not respecting that they may not be just like oneself. It’s far too easy to trample, to damage, to stamp hard on sensitive toes.

Kari Sperring was talking about an interesting and not a little unsteady position for the contemporary fantasy novelist – writing about a period in history which is still very much in living memory (if not the people who have lived through the period themselves then certainly through their direct descendants, sons and daughters whose connection with that particular era may not be direct experience but certainly first-hand accounts thereof). It is something that I myself have had cause to think about in my own work.

My novel “The Secrets of Jin Shei” was based on a time and place very remote from its target (Western, English-speaking) audience – a dim-past Imperial China, reimagined to suit my purpose. Because the original of this vision was so very very long ago, and because it was geographically and culturally so removed from my readers’ own experiences, I had a bit of wiggle room here. I researched things diligently to make sure I could get what details I COULD get right straight, so that the setting would gain in believability and verisimilitude. But my research was of necessity limited to secondary sources and things I read in translation because any records of the time (if any fragile original ones still existed) would not be in a language that I could hope to understand. I did my best, created a world which I called Syai, a land that was “like” Imperial China and not the place itself.

My novel “The Secrets of Jin Shei” was based on a time and place very remote from its target (Western, English-speaking) audience – a dim-past Imperial China, reimagined to suit my purpose. Because the original of this vision was so very very long ago, and because it was geographically and culturally so removed from my readers’ own experiences, I had a bit of wiggle room here. I researched things diligently to make sure I could get what details I COULD get right straight, so that the setting would gain in believability and verisimilitude. But my research was of necessity limited to secondary sources and things I read in translation because any records of the time (if any fragile original ones still existed) would not be in a language that I could hope to understand. I did my best, created a world which I called Syai, a land that was “like” Imperial China and not the place itself.

The follow-up to this book was a different story.

“Embers of Heaven” is a standalone novel which takes place in my China-analogue land, Syai, some 400 years after the events of the previous book… and places the action, here in my pseudo-China-that-never-was, directly in the path of what in THIS world was to become known as the Cultural Revolution.

And here I collided with a little bit of the drama that Kari Sperring talks about concerning the Blitz. The Cultural Revolution LIES WITHIN LIVING MEMORY. There are many, many ways of trampling on people’s feelings and memories here, a huge potential of messing up royally, particularly since (once again) my research, while copious, was confined to translated works of every stripe and I had no means of doing direct original-source research on the matter. Yes, I read thirty seven books to write one. No, I don’t know if this was remotely adequate. Because of what I found in those books.

The truth is that before I began doing this research I was aware of the Cultural Revolution in the manner in which an outsider who is interested in culture and history of the world might be aware of it – in global terms, with one or two specific incidents where memory hooked and held. I knew the principal players and (in broad strokes) their roles and involvements in the events of the Cultural Revolution. But when I began to look at the finer detail of the era I quickly realized that there was a good reason why few people have tried to set a fantasy in this particular time period – because the TRUTH reads so much like horror fantasy that it is almost impossible to deal with in a fictional construct. If I had just used some of the things I found out, verbatim, I would have run afoul of not one but two separate and distinct traps.

The first was that the fellow outsiders, like myself, the Western audience of the book, would never have believed that any of it could possibly have happened in exactly the way that it did because the things that people are capable of doing to one another are frankly mind-bending.

The second was that those insiders who might have lived through the era themselves, or their descendants who know about the time through family stories, would have known the truth which I skirted, and for them it is quite possible that I did not go far enough, that they might feel that I had taken a cruel and vicious moment of their own history and hung a fantasy narrative on it, thereby arguably cheapening the experiences of the survivors (much like Kari Sperring feels about the Blitz and Connie Willis’s treatment of it).

But this was a story that called out to me, and needed to be told – and so I read and I read and I read and I researched, I have tons of scribbled notes, I have a library of books on contemporary Chinese histories and biographies and memoirs and poetry and coffee-table books with incredible photographs. And in the end, when I was ready to write, I had to tell myself that I had enough. And believe in the material, and my own ability to deal with it, sufficiently to launch into the story that I wanted to tell.

“Embers of Heaven” turned out to be… more of a love story than I had anticipated, and between an unlikely pair of lovers, at that. But the background of that unexpected romance was pure raw chaos of revolution, of ideals at their worst (when they’re being pursued regardless of the cost to anyone who stands in their way, however inadvertently), of harrowing tragedy, of joy scrounged from scraps where one could and treasured for its very rarity in time and place, of hard lessons learned the hard way. It was a book where the smiles came from beneath eyes brimming with tears, and were all the more precious for that.

When a writer turns to material such as this, material not innately familiar and yet still viscerally accessible to other people, to strangers, whom the author might never cross paths with in this lifetime, it’s like crossing the Niagara Falls on a tightrope while carrying someone else’s child on his or her shoulders. It’s exhilarating, yes, and if achieved without tragedy it’s a potential source of great pride and accomplishment. But it’s also fraught with potential drama and even tragedy.

And this, the latter, is something that any writer worth their salt is constantly aware of.

In the end, writing the Other is a basic and fundamental question of respect. You take someone else’s life and experiences and you mold it all like clay and make from it something rich and strange – and there are plenty of traps that you can blunder into. You either make it all into something bitterly familiar but twisted out of true to the people who lived the original, or else transmute it into what is to those people an alien thing that they cannot identify with at all. And it is difficult to say which of those I would call the greater failure of story, and of writer.

And yet… without trying, without telling the stories that call out to you, you cannot achieve anything at all, and in some senses even a failure is better than silence. Respect also means that if you have made a blunder and it is pointed out to you by someone who knows better you don’t defend the wrong choices you may have made but you accept the fact that you may have erred and learn how better to find, learn, and express the truths which you somehow failed to grasp at first pass.

To those who choose to make their way into non-familiar near-contemporary cultures and contexts and make them a setting for a rich new fantasy world, to take their chance and write the Other to themselves, I say this. You will make mistakes. This is inevitable. The way to deal with them if pulled up on them is to admit them, accept them, and learn from them.

The key word here is grace – and you may have to raid your stockpiled reserves of it, because accepting rebukes from those who have a right to mete them out requires grace, sometimes a great deal of it, on the writer’s behalf. But grace and respect will take you a long way… and the rewards of writing the Other, and meeting with at least some degree of success, are magical, indescribable.

The jin-shei books provided those rewards to me.

There was the dignified, white-haired Chinese woman who sat in the audience at my first public reading event, and made me quail – here was somebody who would know, with an instinct born of the simple fact of being a bona fide part of this culture which I had inspired my story, if I had screwed up. At the end of my reading she brought her copy of the book for me to sign and said, with a sigh, “A part of me WISHES that you were Chinese.”

There was the day that I was met at a book signing by a woman with a Chinese adopted daughter for whom she wanted a copy of “Secrets of Jin Shei” signed. I was humbled and proud to do so – but I cannot begin to tell you about what filled my heart when the rest of that encounter played out, when the mother thanked me and told me that she would treasure the book and give it to her daughter to read “when she was old enough to understand her heritage”, and I finally asked how old the child was now… and the mother said, “Four.” She had bought my book to hold in trust and treasure for a child barely more than a toddler, who had maybe a decade to go before she could be considered old enough to read and understand a book such as I had written. But the fact that her mother considered the book valuable enough for this to even be a consideration… well, I cried. It still remains one of the proudest and most treasured moments of my entire writing career.

It showed me that I had met the Other, and that a measure of mutual understanding had been achieved.

That this was POSSIBLE.

The next time I face this particular task, it will be no less daunting a prospect – and yes, I will marshal Grace and Respect once again as my wingmen. But even then, even when I understand the things that need to be done and achieved in order to produce something worthy of its own existence there will always be that small voice of warning – you are boldly going where nobody dared go before, and here there be dragons.

And yet I will go. And I will brave the possibility of being greeted by something breathing fire.

Because this is what we do, those of us who live with words and ideas and dreams.

We make them into Stories.

July 4, 2012

David Constantine - Steampunk Before The Age of Steam

David Constantine is the author of steampunk/alternative history THE PILLARS OF HERCULES (Night Shade Books, March 2012), and can be found on the web at www.thepillarofhercules.com. As David J. Williams, he’s also the author of the Autumn Rain trilogy. Interestingly enough, David does not personally run on steam, but is instead platypus-powered. He may or may not have a Hello Kitty tattoo. (And I really need to stop writing introductions when I’m overtired…)

David Constantine is the author of steampunk/alternative history THE PILLARS OF HERCULES (Night Shade Books, March 2012), and can be found on the web at www.thepillarofhercules.com. As David J. Williams, he’s also the author of the Autumn Rain trilogy. Interestingly enough, David does not personally run on steam, but is instead platypus-powered. He may or may not have a Hello Kitty tattoo. (And I really need to stop writing introductions when I’m overtired…)

#

Steampunk sits astride the SF landscape, a clanking smoking beast. And while it started off focused on the Victorian era, some of the most compelling modern steampunk places it in entirely different contexts, the most notable being fantasy and postapocalyptic. Yet—when we consider the sheer volume of stories and novels cranked out—there remain good reasons for the subgenre’s ongoing fascination with the 19th century. As a displacement of anxieties regarding technology, steampunk conjures up an alternative reality that at once both minimizes the birth pangs of industrialization and distracts from the current predicament in which such industrialization has landed us. The societies we glimpse in Victorian steampunk are—with some notable exceptions—idealized; we see the airships and parasols, but rarely the mass graves around the rubber plantations……we listen in on drawing room conversation, but rarely hear the roar of the Vickers guns as they mow down Hostile Natives who’ve fallen behind the Curve of Progress.

So when we consider steampunk that features other “real” time periods—and many recent works have done so—we have to be careful. We’re dealing with a literature that offers a view through a glass darkly; that can bring new light to our relationship with technology, but also has a manifest tendency to idealize (or demonize, for that matter). When I positioned steampunk in the ancient world for my recent novel, I was trying to navigate that tension, in addition to tapping into my longstanding interest in the classical age. What I didn’t realize when I started out is how much steampunk was in that world already. Heron of Alexandria invented the steam engine itself in the first century A.D. (yes, you read that right), but the device was seen as little more than a curiosity. And Archimedes designed weapons known as steam guns; it’s not known whether he actually built them, but a team at MIT recently constructed a prototype using his diagrams.

But it’s precisely that lack of knowledge that plagues us in getting to the reality of Just What Was Really Going on Back Then. Ninety percent of the scrolls penned by ancient writers perished in the Dark Ages, and those writers weren’t generally given to discussions of technology, since they were—by and large—aristocrats who left such things to artisans, manual workers and other such lowlives. Yet every once in a while we get a tantalizing glimpse. In the first century B.C., a Roman ship sank off the Greek island of Antikyhera; twenty millenia later, when it was recovered, archeologists found a device that’s come to be known as the Antikythera mechanism: a precise model of the heavens, featuring more than 70 gears and so elaborate that it’s been called the world’s first analog computer. Had we not dug up this device, we would have had no clue it existed. There are no hints of it in the textual record, which underscores just how little we know about a world so much of which has been lost. We tend to see past societies—particularly those that existed two thousand years ago—as primitive, but the ancients had machines that leave us marveling even today.

But it’s possible to take such a sentiment too far. Without splitting hairs over the blurry boundaries between steampunk and its gearpunk and clockpunk cousins, we’re left with the question of what prevented such technology from not being more pervasive in the ancient world. Specifically, why didn’t that world move to a new level, in the same way that the agrarian economies of the 18th century became the industrialized societies of the next? The dynamics underpinning the “take off” phase of industrialization are too complex to be examined in detail here, but one issue that comes up again and again is the necessary catalyst: i.e., devices only see proliferation and/or mass production if there is incentive for their use.

Which, arguably, there wasn’t. It’s not like the ancient world lacked the profit motive of modern capitalism…far from it. But it was what the ancient world had in abundance that mattered: slaves. Every single field of industry was reliant on slave labor, to the extent that slavery was an integral part of the class structure. Slaves could hope to be freed, and rise in stature, and a few of them went on to rule empires. But the institution of slavery went unchallenged, regardless of who was in charge. Given such a ready supply of slaves, the very idea of labor-saving devices remained stillborn. And it’s worth noting that—even if one wasn’t enslaved—the vast majority of the society lived lives that were nasty, brutish and short. Examining the ‘what-if’ ramifications of steampunk thus becomes, ironically, a means of throwing that fact into sharp relief. And—regardless of what time period it focuses upon—in showing us roads not taken, steampunk underscores just us how far we have yet to go to realize technology’s promise.