Alexander J. Motyl's Blog, page 25

May 6, 2012

The Regionnaire-Burson-Marsteller Axis

The Regionnaires must be getting desperate. When the vast majority of Ukraine’s population thinks of you as thugs, crooks, and vandals a few months before an election you can’t possibly win, there’s only one thing to do. No, not go straight, silly.

You go to Burson-Marsteller, of course, a self-styled “leading global public relations and communications firm” that has a special relationship with the world’s rogues. You pay B-M a ton of money and you hope they can remove your stench.

Andrew Rettman of the EUobserver broke the story on April 27th:

Robert Mack, a senior manager at Burson-Marsteller, told EUobserver: “Our brief is to help the Party of Regions communicate its activities as the governing party of Ukraine, as well as to help it explain better its position on the Yulia Tymoshenko case.” One of his staff said it was hired “several weeks ago.”

(Tip to Mr. Mack: a political party isn’t supposed to have a “position” on what the Yanukovych regime insists is a case for independent courts, but no matter.)

Here’s how the firm describes its mission:

Clients often engage Burson-Marsteller when the stakes are high: during a crisis, a brand launch or any period of fundamental change or transition. They come to us needing sophisticated communications campaigns built on knowledge, research and industry insights. Most of all, clients come to us for our proven ability to communicate effectively with their most critical audiences and stakeholders.

The Regionnaires are the latest in a long list of clients reaching out to B-M “when the stakes are high.” According to the Guardian:

Burson-Marsteller is the company that governments with poor human rights records and corporations in trouble with environmentalists have turned to when in crisis. The world's biggest PR company was employed by the Nigerian government to discredit reports of genocide during the Biafran war, the Argentinian junta after the disappearance of 35,000 civilians, and the Indonesian government after the massacres in East Timor. It also worked to improve the image of the late Romanian president Nicolae Ceausescu and the Saudi royal family. Its corporate clients have included the Three Mile Island nuclear plant, which suffered a partial meltdown in 1979, Union Carbide after the Bhopal gas leak killed up to 15,000 people in India, BP after the sinking of the Torrey Canyon oil tanker in 1967 and the British government after BSE emerged. In the past few years it has acted for big tobacco companies and the European biotechnology industry to challenge the green lobby and counter Greenpeace arguments on GM food.

Nice company the Regionnaires are keeping, eh? But here’s the good news. First, at least the Regionnaires appear to understand that they’re rogues. From self-knowledge may come, well, something. Second, and more important, Burson-Marsteller may praise itself as much as it likes, but does anyone have any doubts about the villainy of the Nigerian, Indonesian, and Saudi governments, as well as the Argentine junta and Nicolae Ceausescu? Of course not. Which goes to show that, despite its hefty fees and inflated claims, B-M is a bust.

And then consider the enormity of the task before B-M. The Nigerian and Indonesian governments could claim to be defending the integrity of their countries. Saudi Arabia could say it’s the linchpin of Middle Eastern stability. The junta could insist it was saving Argentina from the evils of communism. Ceausescu could plausibly argue to have guaranteed Romania’s independence from the Soviet Union. What can the Regionnaires declare as an achievement? Their domestic policy is a wreck, and their foreign policy is a shambles. They’re endangering Ukraine’s integrity, promoting left- and right-wing extremism, and undermining the country’s independence. True, the Yanukovych Family has amassed a fortune, but that’s hardly likely to figure at the top of Burson-Marsteller’s PR campaign.

I pity Mr. Mack. He has to present the mafia as Greenpeace and Al Capone as Mother Theresa. Like finding the square root of -1, it can’t be done, no matter how much you get paid and how much you strain the truth.

Oh, by the way, Burson-Marsteller claims to have what its website calls “values.” As you read this section, try not to laugh too hard:

Honesty

We undertake to be honest in all our professional dealings, including all external professional contacts. We undertake never knowingly to spread false or misleading information and to take reasonable care to avoid doing so inadvertently.

We also ask our clients to be honest with us and to never request that we compromise our principles or the law.

We take every possible step to avoid conflicts of interest.

Integrity

We will only work for organisations that are prepared to uphold the values of transparency and honesty in the course of our work for them.

Our clients are involved with some of the most contentious issues of the day. It is part of our job to provide communications assistance to those clients. We undertake to represent those clients only in ways consistent with the values of honesty and transparency both in what they do and in what we do for them.

We respect the views of employees who have serious concerns about working for any specific client or on any particular assignment. No employee will be required to work for a client inconsistent with his/ her conscience. We will consider our employees views in the Firm’s decision to work on a particular client.

Still laughing? Stop and appreciate the seriousness of the moment. B-M wiz Robert Mack has donned his thinking cap and, with Regionnaire enforcers watching, is about to start sweating bullets. Not to worry, Bob: just blame your failure to square the circle on Yulia Tymoshenko. But do so with honesty and integrity, please.

April 26, 2012

Tymoshenko Beating: Business as Usual in Yanukovych's Ukraine

It had to come to this, of course. When thugs throw an innocent person in jail, how can they resist showing her who’s boss? How can they resist beating her up?

They can’t. And, in Viktor Yanukovych’s Ukraine, they didn’t.

It happened on Friday, April 20th, shortly after 9 p.m., and the victim of the Regionnaire assault was the recently incarcerated opposition leader and former prime minister, Yulia Tymoshenko. Here’s her description of the beating:

At around 21:00 my fellow prisoner was taken out of her cell and shortly thereafter three enormous men came into mine. They approached my bed, covered me with a bed sheet, and began to remove me from my bed, while applying brute force. Desperate and in pain, I began to defend myself, but received a hard punch in the gut. They twisted my hands and feet, and I was taken outside in the bed sheet. I thought that this was my end. The unbearable pain in my back and my fear led me to scream and call for help, but I received none. At some point I simply lost consciousness as a result of the terrible pain and came to in a hospital.

Naturally, the Regionnaires deny all wrongdoing. As the deputy head of the State Penitentiary Service, Serhii Sydorenko, put it, “With respect to the beating, I can state with complete certainty that there was none.” Too bad the Parliament’s human rights ombudsman, Nina Karpacheva, disagrees: “I state that transporting Tymoshenko in this manner represents brutal conduct and may be considered torture” according to a variety of human rights conventions. To which, unsurprisingly, the leader of the Regionnaire parliamentary faction, Oleksandr Yefremov, responded by claiming that Karpacheva is prejudiced and is just angling for a top spot in the opposition.

Yeah, right.

I suppose it all depends on what you mean by a beating. In Regionnaire Land, a punch in the gut is business as usual. A real beating involves at least a bit of blood and a few broken bones. Heck, that “bedsheet” thing was probably a sign of endearment! And besides, wasn’t the broad just asking for it?

I suppose it’s possible that Tymoshenko punched herself in the stomach, and that her subsequent decision to go on a hunger strike is just grandstanding, but the long-standing Regionnaire association with thugs, pogromchiks, fisticuffs, violence, and sexism surely suggests otherwise. Tymoshenko’s vivid description of being maltreated is rather more credible than avowals of innocence by the same people who attributed Viktor Yushchenko’s horrible disfigurement in 2004 to too much booze.

The only real question is: why? Why in God’s name would the Regionnaires be so dumb as to hasten Tymoshenko’s transformation into a martyr and a symbol of resistance?

Part of the answer is, to quote Forrest Gump’s mom, because “stupid is as stupid does.” And, to tell the truth, the unique amalgam of stupidity and thuggishness that the Regionnaires have managed to perfect may be sufficient to explain the beating. After all, part of the Regionnaire job description is to act like big clods with heavy fists.

But let’s assume they actually hoped to achieve something with the beating. What could that be?

It could be that the boys in the prison were told to rough up Tymoshenko for having expressed an impassioned critique of the regime in an interview published on the very day of the beating. Here’s how she described Yanukovych’s Ukraine:

Contemporary Ukraine is a combination of “the island of Dr. Moreau” and Orwell’s 1984…. They’re making us into a nation of losers—without historical memory, without national pride, without positive economic prospects and a European future. They’re building a country of one family—a family with a large appetite or, rather, bulimia, a miserable IQ, and pretensions of eternal power.

It could also be that the regime was trying to send a message to Ukrainians in general, and to the democratic opposition in particular: step out of line and you will suffer the consequences. Desperate authoritarian regimes the world over act that way before critical elections they know they’ll lose. If that’s the case, expect beatings of opposition politicians to increase as the October parliamentary elections approach.

It won’t work, of course. Ukrainians won’t be intimidated anymore by an incompetent regime that needs to pummel defenseless political prisoners. And the rest of the world will only become even more outraged by President Yanukovych’s progressive self-transformation into a pariah.

All of which raises a terrifying question. If the Regionnaires don’t understand that beating Tymoshenko is both wrong and dumb, won’t they be tempted to silence her permanently? Ukraine and the world would be up in arms, but the Regionnaires wouldn’t care—or even notice. And besides, isn’t the broad just asking for it?

April 23, 2012

Yanukovych’s Shady Royalties

President Viktor Yanukovych has stepped into another scandal, this one over his assets. He declared his total income for 2011 as being 17,362,024 hryvnia, which, at 8.03 hryvnia to the dollar (the exchange rate on April 15th), comes out to $2,163,257.

Not bad enough for a populist president who claims to be one of the regular folk, but the real scandal concerns the source of Yanukovych’s money. A mere 757,615 hryvnia ($94,396) constitute his presidential salary, while 155,409 hryvnia come from dividends and interest. (He’s got 14,521,454 hryvnia stashed away in banks.) So what’s the source of the remaining 16,449,000 hryvnia ($2,049,497)?

Turns out those are his “author’s royalties” and other income due to “intellectual property.” How so? you ask. Well, according to the UNIAN Information Agency, the Donetsk-based Novyy svit (New World) publishing house paid Yanukovych the money for the rights to four books Yanukovych penned from 2005 to 2010, as well as for “literary works that the author will create in the future.” The prolific Prez’s books are primarily collections of his speeches and articles, which, as one democratic website points out, “are usually distributed for free by his party.” As to the literary works, let’s not even go there.

So is all this stuff really worth two million bucks? Seems like a stretch to me. Yanukovych ally Volodymyr Semynozhenko, the head of the State Agency for Science, Innovations, and Informatization, disagrees: “I didn’t speak with the president about this issue, but, as far as I understand, we’re talking about an advance for the future memoirs of the head of state. I think Viktor Yanukovych has agreed to give a long interview after 2020 and to relate his dramatic life’s destiny, his work as prime minister, how he experienced the Orange Revolution, stayed in opposition in 2005 and 2008–2009, and finally succeeded in winning the presidential elections and introducing reforms.” What’s the big deal? asks Semynozhenko. After all, Ronald Reagan, George W. Bush, Barack Obama, and Bill Clinton also got big advances.

You gotta wonder what’s scarier: the thought of Yanukovych writing fiction or the preposterousness of Semynozhenko’s comments. Say what you will about those American presidents, but they were world-historical personalities whose memoirs were guaranteed important and large readerships. Are there more than 100 Ukraine experts (sorry—99 not counting myself) who’ll care to buy Yanukovych’s memoirs? A nice Ukrainian folk saying is quite appropriate here: “As the smith is placing a horseshoe on the horse, the frog extends its leg.”

By the way, note that Semynozhenko assumes that Yanukovych will be around after 2020 to give long interviews. Given the Prez’s current ratings, his winning the 2015 election fair and square is virtually impossible. And if Yanukovych just grabs power and has himself declared president again in opposition to the popular will, he may be too busy running from Interpol in 2020 to have time to sit down for a chat.

Now, the Regionnaires may be dumb, but they know money, and no self-respecting Regionnaire can possibly believe that Yanukovych deserves so large an advance for books that nobody will read. So what’s going on? According to the opposition Ukrainska Pravda website, the New World publishing house is behind Yanukovych’s scandalous book, Opportunity Ukraine, which wasn’t only a snooze, but, after it was revealed that parts had been lifted from other published sources, was quickly withdrawn from the market—at some loss, I assume, to the state budget.

The director of the press is one Hennadi Ustymenko, who, as it turns out, is also the “head of the transportation-technical administration of the Administration of the State Special Service of Transportation of the Ministry of Infrastructure.” What the hell is that? you wonder. Turns out that the “State Special Service of Transportation is a specialized state organ of transportation in the Ministry of Transportation and Communications of Ukraine, which is intended to ensure the reliable functioning of transportation in times of peace and under conditions of war and emergencies.”

Got that? Well, if you ever wondered just how impenetrable and absurd Ukraine’s bureaucracy is, the good news is that now you know. By the way, it’s even funnier. On January 12, 2012, Ustymenko was appointed a member of the Ministry of Economic Development and Trade’s “Offset Commission.” What’s that? As with Yanukovych’s literary works, let’s not even go there. Oh, and Ustymenko is apparently affiliated with Biznesrazvedka.RF, a marketing firm that gathers “business intelligence.” If you want to visit the multitasking Ustymenko and get your own memoirs published, New World is on Batyshcheva Street 2-a in Donetsk.

Anyway, the bottom line is pretty clear. The shady Ustymenko is part of the state bureaucracy, and New World appears to be at the beck and call of the president. I figure that a good chunk of the state budget—lemme take a wild guess and say it’s about 16 million hryvnia—somehow made its way to Ustymenko’s publishing outfit, which in turn … Well, let’s not even go there.

The other thing that’s clear is that Yanukovych has been stung by criticism of his authorial lucre. On April 15th, Orthodox Easter, he told journalists: “This year the money I received from the publication of some of my books will be directed only at helping the poor, the ill, and of course above all children.”

The ease with which Yanukovych donated the $2 million suggests that he regards it as chump change, the price of a cup of coffee. Only a man who’s worth billions could think that way.

April 12, 2012

Extremism in Ukraine

Which Ukrainian political parties are extremist? Most people would point to the right-wing Svoboda party under the leadership of the charismatic demagogue, Oleh Tyahnybok. And they’d be right. Svoboda (or, ironically, “Freedom”) is xenophobic, radical, and anti-democratic: the three defining features of extremism.

But they’d be only partly right. No less xenophobic, no less radical, and no less anti-democratic are two other political groups—the Communist Party of Ukraine and the Party of Regions. Suffice to say that Ukraine’s Communists are still Stalinist and proud of it. As for the Regionnaires, two years of their rule have relegated Ukrainian language, culture, and identity to Bantustans, exacerbated tensions between Ukrainian speakers and Russian speakers, intentionally promoted Russian chauvinism and Svoboda extremism, efficiently dismantled democracy, bequeathed the economy to rapacious corruptioneers, squeezed civil society, and eroded freedom of the press, speech, and assembly. If that isn’t extremism, I don’t know what is. Contrary to President Viktor Yanukovych’s assertions that he is a moderate, the fact is that he is an extremist par excellence.

But to put the matter in these terms misses the whole picture. After all, Svoboda captured a mere 0.76 percent of the vote in the 2007 parliamentary elections. It does have influence in Ternopil Province and the city of Lviv, but it is also, despite Tyahnybok’s assurances to the contrary, never likely to increase its share of the total vote in Ukraine over five percent. Five percent is five percentage points too many, but it’s also a tiny amount. Not so with the Communists, who polled 5.39 percent in the parliamentary elections of 2007 and 38 percent in the presidential elections of 1999. Not so, as well, with the Party of Regions, which got 34 percent of the vote in the 2007 parliamentary elections and whose candidate, Yanukovych, won 49 percent in the presidential elections of 2010. Since Yanukovych’s party effectively stole the Communist vote, the Regionnaires may be viewed as a non-ideological version of the former Communist machine. The Communists were extremists because that was the best way to build Stalinism; the Regionnaires are extremists because that’s the best way to steal. Choose your poison.

As odious as Svoboda is, therefore, the main extremist threat to Ukraine comes not from it, but from the Regionnaires and Communists. Indeed, unless you believe in miracles, Svoboda will never become a major political force, whereas the Regionnaires are and will long remain one. Moreover, Regionnaire extremism is primarily responsible for galvanizing Svoboda extremism. The moral for Ukrainian democrats should therefore be clear: avoid collaborating with extremists of all stripes, whether Svobodites, Regionnaires, or Communists.

Unfortunately, reality is more complicated. The Regionnaires are in power and will do everything it takes to stay in power. Should democrats shun and oppose them, and thereby lose every chance of influencing the course of events, or should they collaborate—or is the better word cooperate?—with them and hope to moderate their extremism? Power is a heady brew, and Yanukovych knows full well that he can co-opt democrats by offering them symbolically important positions in his regime. On the other hand, there is a case to be made for infiltrating the regime and attempting to change it from within.

Who’s right? What’s clear is that both stances are bets. Principled opposition to Regionnaire rule could turn out to be right or it could consign the democrats to impotence. Pragmatic cooperation could turn out to be effective or it could consign the cooperators to collaborationist infamy. Petro Poroshenko, the millionaire chocolate-maker and former good guy, has just joined the Yanukovych government as minister of economic development and trade. He obviously thinks that working with extremists might make a difference for the collapsing Ukrainian economy. If you agree, buy Roshen chocolates. If you don’t, switch to Hershey’s.

Naturally, if these qualms are valid with respect to the Regionnaire extremists, they must also be valid with respect to the Communist and Svoboda extremists. Back in the days of the USSR, some well-meaning Ukrainians chose to become principled dissidents while others joined the Party. The USSR’s collapse made the former look right, but for most of Leonid Brezhnev’s rule many viewed them as hopelessly unrealistic idealists. By the same token, some Ukrainian democrats are willing to include Svoboda in an anti-regime electoral coalition, while others are not. Their dilemma is identical to that faced by Russian democrats, who have to decide whether an anti-Putin coalition should or should not have room for nationalists and communists. If you think collaborating with Regionnaire extremism is permissible, you have no choice but to permit collaboration with Communist or Svoboda extremism. If you think all extremists are equally odious, you have no choice but to view cooperation with the Regionnaires as as wrong as cooperation with the Communists or Svoboda. Unless, of course, you believe that extremists with power are less odious than extremists without power, in which case you won’t collaborate with Svoboda until they make it into office.

Fortunately, democrats may be able to sidestep these moral dilemmas—but only at this point in time—precisely because the Regionnaire regime is crumbling, while the Stalinists and Svoboda are likely to remain minority parties (or so I hope). The democrats don’t need any of them to regain power. If they want to win the trust of the people, they should position themselves as anti-extremists and don the mantle of tolerance, moderation, and inclusion—the opposites of xenophobia, radicalism, and anti-democracy—and make the case for an anti-extremist Ukraine in which people, and not thieves, thugs, chauvinists, and anti-Semites, will be served. After all, Ukrainians want to live normalno, and normality is anything but extremist.

April 5, 2012

Ukrainian Stereotypes in Holland’s ‘In Darkness’

Go see Agnieszka Holland’s In Darkness, both because it’s an excellent film about the Holocaust in wartime Lviv and because it demonstrates just how deeply rooted some ethnic stereotypes can be.

The story is simple: an anti-Semitic Polish sewer worker and part-time crook, Poldek Socha, finds himself in the unexpected position of hiding a group of Jews in Lviv’s sewers. At first, he does so only for money. In time, he abandons his anti-Semitism and acts with altruism. The film ends with the liberation of Lviv by the Soviets and the emergence of the surviving Jews from the sewers. “These are my Jews!” Socha beams. “These are my Jews!”

In an interview, Holland emphasized what she thought was one of the film’s strong points: its avoidance of one-dimensional characterizations. Here’s what she says about Socha:

First of all, the main character, this Polish guy, was ambiguous, both hero and not hero, and a very simple, ordinary man, not very good. What was always interesting for me was not the mystery that people can be terrible. I think humanity has a tendency to be terrible. What always surprises and intrigues me is that in those circumstances somebody acts in a good way, especially somebody who doesn’t have deep reasons or preparation to do so.

Socha doesn’t think about what will happen, what he will do. He just acts. What I thought was an interesting, dramatic part of the story was that you don’t know what he will do. Even to himself he doesn’t know. It’s like walking on a wire, and at any moment he can slip to one side or the other.

And here’s what she says about the Jews hiding in the sewer:

The Jewish characters aren’t one-dimensional angelic, they are full-bodied human beings with anger, sex, weakness, and selfishness, and generosity and love as well. That was another thing that irritates me in English-language Holocaust movies: that in most of them the Jews are turned into some kind of non-living, positive stereotypes. I think that in doing so, in some way you are killing them again. They become unreal.

Holland is right to state that multi-dimensional portrayals can only enhance our experience and understanding of the Holocaust. Unfortunately, she restricts multidimensionality to Poles and Jews and resorts to straightforward stereotyping when it comes to Ukrainians. That she does so unwittingly just goes to show how “taken for granted” some stereotypes are.

There are three Ukrainian characters in the film. By far the most domineering is a Ukrainian policeman by the name of Bortnyk. He’s fanatically pro-German, fanatically anti-Semitic, and fanatically pro-Ukrainian. His eyes glisten when he speaks of hunting down Jews and, naturally, he loves to drink. He appears for minutes on end, arguably being the second most important character in the film. He identifies himself—and is identified as—Ukrainian. And, lest the point escape you that the external appearance of Ukrainians shouldn’t mislead you about their internal brutishness, he is, unlike the dumpy Socha, tall, dark, and handsome. Indeed, Bortnyk even comes across as worse than the Germans, who are portrayed only as background brutes. The Ukrainian is a living, breathing embodiment of evil, whereas the Nazis have no personality whatsoever. Not surprisingly, Bortnyk becomes stereotypically “unreal,” and the film suffers aesthetically as a result.

Two other Ukrainians make bit appearances lasting a few seconds apiece. One is a peasant woman selling vegetables who expresses regret over the killing of Poles. The other is a worker who helps one of the Jews get through town. Neither of these two characters is identified as Ukrainian, and the only way you’d know they are is if you understand the language. If you don’t, you’re liable to think they’re two of the many more or less nuanced, multi-dimensional Polish characters. And besides, the two Ukrainians appear on screen for a total of about 30 seconds.

Here’s how Yale historian Timothy Snyder describes Holland’s portrayal of Ukrainians:

Poldek has a Ukrainian friend, Bortnik, who serves as a chief of the local police. This friendship saves Poldek once, but has its risks, since among the tasks of the police are the discovery and murder of Jews. Bortnik comes to Poldek’s house late at night drunk and demands sustenance; Poldek’s little daughter, rubbing her eyes in bed, reminds her father that they were saving food for “the Jews.” She then realizes what she has done, and convinces Bortnik that by “Jews” she meant her dolls, which, she says, came from the ghetto. In a story of interaction between Poles and Jews, the natural tendency would be to export local evil as much as possible to the third nationality: the Ukrainians. Without at all disguising the horrible local politics of occupation, Holland carefully balances Ukrainian villains with sympathetic Ukrainian characters. One of the Jews in hiding smuggles himself into a concentration camp to see if the younger sister of the woman he loves is still alive. This heroism is enabled by a Ukrainian, who performs the indispensible [sic] logistical work and refuses payment.

Carefully balances, indeed! Imagine a German-language film with multi-dimensional German characters and three Jews. Two speak Yiddish (which sounds awfully like German to the untrained ear), are never identified as Jewish, and come off positively for all of 30 seconds. The third identifies himself as Jewish, is a fanatical Zionist, is depicted as a blood-sucking banker, and is on screen for 10 to 15 minutes.

I don’t doubt that both Holland and Snyder would find the film aesthetically flawed and anti-Semitic.

Photo Credit: Bundesarchiv, Bild 101I-187-0203-28A / Gehrmann, Friedrich / CC-BY-SA

Ukrainian Stereotypes in Holland's 'In Darkness'

Go see Agnieszka Holland's In Darkness, both because it's an excellent film about the Holocaust in wartime Lviv and because it demonstrates just how deeply rooted some ethnic stereotypes can be.

The story is simple: an anti-Semitic Polish sewer worker and part-time crook, Poldek Socha, finds himself in the unexpected position of hiding a group of Jews in Lviv's sewers. At first, he does so only for money. In time, he abandons his anti-Semitism and acts with altruism. The film ends with the liberation of Lviv by the Soviets and the emergence of the surviving Jews from the sewers. "These are my Jews!" Socha beams. "These are my Jews!"

In an interview, Holland emphasized what she thought was one of the film's strong points: its avoidance of one-dimensional characterizations. Here's what she says about Socha:

First of all, the main character, this Polish guy, was ambiguous, both hero and not hero, and a very simple, ordinary man, not very good. What was always interesting for me was not the mystery that people can be terrible. I think humanity has a tendency to be terrible. What always surprises and intrigues me is that in those circumstances somebody acts in a good way, especially somebody who doesn't have deep reasons or preparation to do so.

Socha doesn't think about what will happen, what he will do. He just acts. What I thought was an interesting, dramatic part of the story was that you don't know what he will do. Even to himself he doesn't know. It's like walking on a wire, and at any moment he can slip to one side or the other.

And here's what she says about the Jews hiding in the sewer:

The Jewish characters aren't one-dimensional angelic, they are full-bodied human beings with anger, sex, weakness, and selfishness, and generosity and love as well. That was another thing that irritates me in English-language Holocaust movies: that in most of them the Jews are turned into some kind of non-living, positive stereotypes. I think that in doing so, in some way you are killing them again. They become unreal.

Holland is right to state that multi-dimensional portrayals can only enhance our experience and understanding of the Holocaust. Unfortunately, she restricts multidimensionality to Poles and Jews and resorts to straightforward stereotyping when it comes to Ukrainians. That she does so unwittingly just goes to show how "taken for granted" some stereotypes are.

There are three Ukrainian characters in the film. By far the most domineering is a Ukrainian policeman by the name of Bortnyk. He's fanatically pro-German, fanatically anti-Semitic, and fanatically pro-Ukrainian. His eyes glisten when he speaks of hunting down Jews and, naturally, he loves to drink. He appears for minutes on end, arguably being the second most important character in the film. He identifies himself—and is identified as—Ukrainian. And, lest the point escape you that the external appearance of Ukrainians shouldn't mislead you about their internal brutishness, he is, unlike the dumpy Socha, tall, dark, and handsome. Indeed, Bortnyk even comes across as worse than the Germans, who are portrayed only as background brutes. The Ukrainian is a living, breathing embodiment of evil, whereas the Nazis have no personality whatsoever. Not surprisingly, Bortnyk becomes stereotypically "unreal," and the film suffers aesthetically as a result.

Two other Ukrainians make bit appearances lasting a few seconds apiece. One is a peasant woman selling vegetables who expresses regret over the killing of Poles. The other is a worker who helps one of the Jews get through town. Neither of these two characters is identified as Ukrainian, and the only way you'd know they are is if you understand the language. If you don't, you're liable to think they're two of the many more or less nuanced, multi-dimensional Polish characters. And besides, the two Ukrainians appear on screen for a total of about 30 seconds.

Here's how Yale historian Timothy Snyder describes Holland's portrayal of Ukrainians:

Poldek has a Ukrainian friend, Bortnik, who serves as a chief of the local police. This friendship saves Poldek once, but has its risks, since among the tasks of the police are the discovery and murder of Jews. Bortnik comes to Poldek's house late at night drunk and demands sustenance; Poldek's little daughter, rubbing her eyes in bed, reminds her father that they were saving food for "the Jews." She then realizes what she has done, and convinces Bortnik that by "Jews" she meant her dolls, which, she says, came from the ghetto. In a story of interaction between Poles and Jews, the natural tendency would be to export local evil as much as possible to the third nationality: the Ukrainians. Without at all disguising the horrible local politics of occupation, Holland carefully balances Ukrainian villains with sympathetic Ukrainian characters. One of the Jews in hiding smuggles himself into a concentration camp to see if the younger sister of the woman he loves is still alive. This heroism is enabled by a Ukrainian, who performs the indispensible [sic] logistical work and refuses payment.

Carefully balances, indeed! Imagine a German-language film with multi-dimensional German characters and three Jews. Two speak Yiddish (which sounds awfully like German to the untrained ear), are never identified as Jewish, and come off positively for all of 30 seconds. The third identifies himself as Jewish, is a fanatical Zionist, is depicted as a blood-sucking banker, and is on screen for 10 to 15 minutes.

I don't doubt that both Holland and Snyder would find the film aesthetically flawed and anti-Semitic.

Photo Credit: Bundesarchiv, Bild 101I-187-0203-28A / Gehrmann, Friedrich / CC-BY-SA

March 29, 2012

Truth and Hopelessness in Luhansk

I recently came across the saddest commentary on Ukraine's eastern provinces that I have ever encountered. It's a video blog by one Stanislav Tsikalovsky from the city of Luhansk. The 34-year-old Tsikalovsky goes by the name of Proctologist. His slogan is: "Believe me, because madmen always speak the truth."

The truth that recently caught the attention of some 30,000 Ukrainians came in a video Tsikalovsky made after a trip to Lviv, in western Ukraine. Here's what he had to say:

I would like to dedicate this video blog to the city of Lviv, which I visited, and to those people who hosted us, showed us their city, and told us about its beauty and prospects for the future. I wasn't sure what to say until I sat down in the Lviv-Luhansk train and arrived in my native Luhansk. I disembarked and understood that, besides crying in front of a camera, I wouldn't succeed in describing the beautiful city of Lviv. And not because there's nothing to say. You understand that quite well, if you've seen my photographs. There are, I'm ashamed to admit, many, many, many interesting things there. But when I stepped onto my native Donbas-Luhansk land and looked around, I saw and understood that we don't even have a future. We have no city authorities and no provincial authorities. And it's not even a question of having no prospects of large-scale change. We have no prospects of any kind of change whatsoever. All that's left for us, for you, is at a minimum for us, the Donbas, to be enclosed with barbed wire and not be let out, so as not to interfere with normal people's efforts to develop themselves and build a good country. And at a maximum, I guess, simply to drink ourselves silly. Bye.

The bit about hopelessness and lack of future prospects is depressing enough. But for a native of Luhansk to recommend enclosing the Donbas with barbed wire is enough to drive one to drink. If Tsikalovsky were a punk with a dog collar and a mohawk, one could dismiss his comments as the rant of an adolescent. But the Proctologist has a university degree in management and has been working for the Luhansk-based Web portal TOP since 2004. And, with a balding pate and intelligent face, he looks as respectable as he sounds.

It's easy to understand Tsikalovsky's despair. Lviv is an architectural, historical, and cultural gem. Its infrastructure is a mess and too many of its streets and buildings require capital repairs, but it feels like a place that will, one day, be a fabulously prosperous town. Small wonder that the Financial Times recently included it on its list of top 10 European "cities of the future."

In contrast, Luhansk is your quintessential Soviet, and Sovietized, city. Obviously, dreadful architecture need not doom a city. As every New Yorker knows, with a little bit of imagination, even ugliness can be made interesting and drabness can be made more livable. But, as Tsikalovsky understands, his city's real problem is that it's still misruled by people who don't see beyond the Stalinist past: "We have no city authorities and no provincial authorities." And note Tsikalovsky's triple emphasis: "We have no prospects of any kind of change whatsoever."

If you want to get a sense of the reality that Tsikalovsky finds so depressing, take a look at a Russian-language film Coal Mine No. 8, by Marianna Kaat of Estonia. It's a documentary about a bunch of kids making ends meet in the depressed coal-mining town of Snizhne, almost equidistant from Donetsk and Luhansk. If you don't understand Russian, don't worry. Just look at the houses, the devastated countryside, and the young boy who goes down into abandoned mine shafts to scrabble for coal, which he then sells or uses to heat his makeshift home. Or take a look at the "fecal geyser" that gushed forth from a break in Luhansk sewage pipes on March 20th. Or consider the wave of suicides that has swept Luhansk Province.

When you're done watching Kaat's film, you may want to draw barbed wire around the Regionnaires who banned it in Kyiv and the Donbas authorities who remain utterly indifferent to the people they claim to serve.

Photo Credit: Riwnodennyk

March 22, 2012

Ukraine: The Yanukovych Family Business

Just when did people start referring to the inner circle around President Viktor Yanukovych as "The Family"? The term is now commonplace, but my impression is that it started entering the political vocabulary of Ukraine about six to twelve months ago, when son Oleksandr joined Viktor Senior and Viktor Junior to form a triumvirate of power holders and all three began promoting their buddies to positions of authority in the government or to positions of unbounded rapaciousness in the economy.

Little Viktor has long been active in the youth branch of the Party of Regions—call them the "Regionnairettes"—and has served as a dutiful member of Parliament, where he's been filmed acting uprightly by voting on behalf of absent comrades (a constitutional infraction, by the way, but what the hell). His big brother, Oleksandr, is the dentist extraordinaire whose mastery of gums and teeth somehow propelled him to the ranks of Ukraine's one hundred richest individuals at precisely the time that Big Viktor was president.

The head of the central bank, the 36-year-old Serhii Arbuzov, is a friend of "The Family," as is the recently appointed minister of finance, the 38-year-old Yuri Kolobov. See the pattern? Where money's at stake, the Yanukovych brothers make sure their pals are in charge, and Dad says, "Da."

Who knows just how much the Yanukovych boys are worth? After all, every dollar of visible wealth is probably matched with another hundred stashed away in hidden assets or foreign bank accounts. And there's lots of very visible wealth, from Junior's fast cars to the Dentist's real estate holdings.

But corruption isn't my point. All authoritarian leaders and their cliques raid state coffers and grow very rich, very quickly. Rather more important is that only very few authoritarian leaders rule by means of bona fide family members. Most prefer to surround themselves with loyal cops, soldiers, and other lugs.

Good ol' Leonid Brezhnev, the man who brought the "era of stagnation" to the Soviet Union, had a "Family" of his own, centered on his corrupt daughter, Galina. Every North Korean leader in the last few decades has relied on his sons. Romania's notorious Nicolae Ceausescu made wife Elena a member of the Politburo and permitted his dissolute son Nicu to harass half the country's women. Saddam Hussein had a stable of powerful, and thuggish, sons. Syria's Hafez al-Assad made sure son Bashar succeeded him. Hosni Mubarak hoped son Gamal would take his place. And where would Cuba's Fidel Castro be without his brother Raúl?

In all these instances, authoritarian rulers employ family members to misrule their countries. The inevitable result is, of course, vast corruption, as evident in Yanukovych's Ukraine as in Ceausescu's Romania or Brezhnev's USSR. But the inevitable cause of rule by family is the ruler's lack of trust in his own supporters and his isolation from both the ruling elites and society. Why would you want your untested offspring to run a country if you had smart elites whom you trusted? You wouldn't. What distinguishes the incompetent son or daughter from the competent policymaker or technocrat is that you, as the supreme leader, can count on the former to follow your every wish and command. You can trust them—or, at least, you think you can trust them. In contrast, smart policymakers, even if they're your supporters, can never be fully trusted. They may decide to jump ship, or worse, to stab you in the back.

The rise of the Yanukovych Family is thus a sign of Yanukovych's growing helplessness. When a president of a big country has to rely on Junior and the Dentist to run the place, you know he's in trouble. And the trouble will only increase. After all, what do Junior and the Dentist know about running a state? Nothing. And would either of them actually tell Dad the bad news or would they be more inclined to sugarcoat it? The latter, obviously. Which means that the more Yanukovych relies on the boys for information and advice, the more misinformed and ill-advised he will be, and the more incompetent and unprofessional his policies will become.

The amassing of Yanukovych Family power heralds nothing less than the fall of Papa Yanukovych. I wouldn't be surprised if Junior and the Dentist were licking their chops and preparing political eulogies.

March 16, 2012

Soft and Hard Power Threats to Ukraine

Ukrainians like to blame their country's ills on "Moscow and the Muscovites," but the UK's highly respected Royal Institute of International Affairs (a.k.a. Chatham House) has just provided good grounds for thinking that their paranoia may be justified.

Take a look at the January 2012 briefing paper, "A Ghost in the Mirror: Russian Soft Power in Ukraine," by two Kyiv-based analysts—Alexander Bogomolov and Oleksandr Lytvynenko. Bogomolov is president of the Association of Middle East Studies, while Lytvynenko is director of research projects at the Foreign and Security Policy Council. Neither is a "nationalist hothead." Both are sober establishment men.

Here are the bullet points of their argument:

"For Russia, maintaining influence over Ukraine is more than a foreign policy priority; it is an existential imperative. Many in Russia's political elite perceive Ukraine as part of their country's own identity."

The problem with existential imperatives is that they are "zero-sum games." If Russia's existence truly depends on Ukraine's nonexistence, then compromise is impossible, at least as long as Russia's rulers perceive Ukraine as part of Russia's identity.

"Russia's socio-economic model limits its capacity to act as a pole of attraction for Ukraine. As a result, Russia relies on its national myths to devise narratives and projects intended to bind Ukraine in a 'common future' with Russia and other post-Soviet states."

Russia's Putinist model is more accurately termed "fascistoid," an ugly word that captures the wretched nature of Vladimir Putin's brand of authoritarianism plus charismatic strongman rule. (For more on this, see "Fascistoid Russia" in the current issue of World Affairs.) The good news is that, since no right-thinking non-Russian elite would presumably want to adopt such a model, even Ukraine's doltish Regionnaires may want to resist Russian soft-power blandishments if they recognize that they are a cover for the hard-power brutality of Putinism.

"These narratives are translated into influence in Ukraine through channels such as the Russian Orthodox Church, the mass media, formal and informal business networks, and non-governmental organizations."

Here's the bad news for Ukraine. Its elites can, in principle, easily say no to Putin and Putinism, but how does one say no to religion, language, and culture?

"Russia also achieves influence in Ukraine by mobilizing constituencies around politically sensitive issues such as language policy and shared cultural and historical legacies. This depends heavily on symbolic resources and a deep but often clumsy engagement in local identity politics."

"Russia's soft power project with regard to Ukraine emphasizes cultural and linguistic boundaries over civic identities, which is ultimately a burden for both countries."

The last two points are especially bad news for Ukrainian and Russian liberals committed to interethnic tolerance and amity. If Russian soft power is focused on creating "disloyal minorities" with intolerant identities, then the ultimate effect will be to promote racism, chauvinism, and intolerance both within Ukraine and Russia and between Ukraine and Russia.

According to the two analysts, the root of the problem is that

the very idea of a Ukrainian nation separate from the great Russian nation challenges core beliefs about Russia's origin and identity. Ukraine hosts the most valuable symbols constituting the core of Russia's national identity—the mythological birthplace of the Russian nation and the cradle of the Russian Orthodox Church along with its holiest places…. From this perspective, the collective goods that bring the majority of Ukrainians together as a nation … appear to be meaningless, second-rate or blasphemous to a large number of Russians. Generations of Russian intellectuals have turned belittling of the Ukrainian language and culture into a part of the Russian belief system alongside anti-Tatar and anti-Muslim stereotypes. But whereas the latter are built around national differences, what makes Ukraine stand out in this list is a dismissive attitude to any assertion that national differences exist. This coexistence between friendship for a "kindred people" and hostility to the Ukrainian nation is what gives relations between Ukraine and Russia their distinctive quality.

More than distinctive, the quality of Ukrainian-Russian relations is, given such a mind-set, necessarily going to be conflictual. Worse, if such dismissive attitudes are part and parcel of Russian identity, then there is no solution short of a fundamental transformation of Russian identity—something that, even in the best of circumstances, will take a long time.

Unfortunately, regardless of the dastardly intentions of "generations of Russian intellectuals," Ukraine's policymakers have compounded their country's problems by behaving as if they were paid agents of Russian hard power. Here's what Edward Chow, senior fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies and an expert on Ukraine's energy, told the US Senate Foreign Relations Committee on February 1st:

I have not met a single Ukrainian or Western geologist who does not believe that Ukraine has the geologic prospects to greatly increase its domestic oil and gas production. … Together with energy efficiency improvements, Ukraine can be more than 50 percent self-sufficient in gas. … Ukraine's oil and gas sector is operated in a totally dysfunctional manner. … In fact, if you were to design an energy system that is optimized for corruption, it might look very much like Ukraine's. You would start with a wholly state-owned monopoly that is not accountable to anyone except the head of the country who appoints the management of this company. It would operate non-transparently…. Domestic production would be priced artificially low, ostensibly for social welfare reasons, leading to a large grey market in gas supply that is allocated by privileged access rather than by price. ... The opaque middleman is frequently paid handsomely in kind, rather than in cash, which allows him to re-export the gas or to resell to high-value domestic customers, leaving the state company with the import debt and social obligations. … Russia may expect to gain full control of [Ukraine's] gas transit system over time, as Ukraine continues to mismanage its energy sector…. The result of this possible scenario is that Ukraine becomes an energy appendage of Russia's.

As Chow suggests, fixing Ukraine's energy problems is technically a piece of cake. All you need to do is stop stealing from time to time. Naturally, no corrupt Ukrainian policymaker—and certainly no Regionnaire policymaker, almost all of whom are by definition corrupt—will put his country ahead of his Swiss bank account.

As Bogomolov and Lytvynenko imply, neutralizing Russia's soft-power assault on Ukraine is also doable. All you need to do is speak Ukrainian from time to time. The Orange governments tried and were denounced by the Regionnaires. And, naturally, no Regionnaire will put his country ahead of his inability to speak a second language.

All of which leaves Ukraine trapped between Russia's hard and soft power. A few more years of Regionnaire indifference and Yanukovych may go down in history as the man who transformed his country into both an energy and identity "appendage" of Russia.

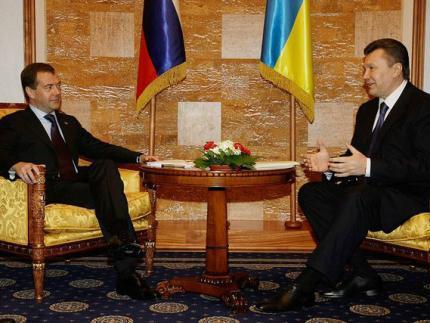

Photo Credit: Russian President Press and Information Office

March 9, 2012

The Mega-Stupidity of Imprisoning Yuri Lutsenko

Throwing opposition leader Yulia Tymoshenko in jail was profoundly dumb, but sentencing her minister of the interior, Yuri Lutsenko, to four years was jaw-achingly, eye-poppingly dumber. After all, Tymoshenko actually posed a threat to President Viktor Yanukovych. She almost beat him in the last presidential election, and she would almost certainly have crushed him in the next one. Worse, as a self-confident woman, she undermined his desperately fragile male ego. To be sure, jailing her also subverted Ukraine's chances of moving toward Europe and exposed it to Russia's predations—strategic considerations that most leaders would have acknowledged as trumping the frailty of their personalities—but at least her imprisonment served some of Yanukovych's immediate interests.

Nothing of the sort can be said about Lutsenko's imprisonment. First, his trial was even more of a farce than Tymoshenko's. Second, the charges were so manifestly petty and stupid—helping his driver financially—as to make even the most fierce of his critics cringe. The anti-Ukrainian Regionnaire apologist Oles Buzyna, for instance, observed Lutsenko's behavior at the trial and concluded that "The clown became a martyr and a victim. As well as a hero."

Third, Lutsenko posed absolutely no threat to anybody. He was never going to challenge Yanukovych, and he was highly unlikely ever again to become a minister after his dismal performance in Tymoshenko's cabinet. At most, he would have become a fringe politician, able to appeal to and mobilize a few thousand followers. There are scores of wannabe leaders like that in Ukraine and one more would have made no difference to Regionnaire rule.

Fourth, only a dolt could believe that his sentencing will scare Ukrainians. Regionnaire legitimacy is nil, Yanukovych's popularity is approaching nil, popular anger is enormous, approaching the explosive range, and societal mobilization—whether of students, miners, veterans, entrepreneurs, writers, or human rights activists—continues unabated. Quite the contrary, sentencing Lutsenko will only make people angrier.

Fifth, freeing Lutsenko would have cost nothing and brought possibly significant dividends. Lutsenko became a martyr, victim, and hero—in a word, a symbol—after he was sentenced. Releasing him on some technicality would have led to some gloating by the democrats, but only briefly, inasmuch as Lutsenko was washed up and not yet a symbol. Indeed, had the Regionnaires been smart enough to free him, they could have claimed to be magnanimous, fair, and just. Most Ukrainians would have seen their self-righteous stance for what it is—bunk—but some might not have, and when you're down to single digits in popular support, every person counts.

Sixth, and most important, not sentencing Lutsenko would have enabled the Yanukovych regime to suggest to the Europeans that it was changing its way, that it was going straight, and that the Tymoshenko verdict was an unfortunate aberration. Like Ukrainians, Europeans aren't as dumb as the Regionnaires think they are, but the signal would have been loud and clear, and it could not have been ignored in Brussels. Had the Regionnaires really been smart, they could even have hinted that the Lutsenko case was a foretaste of things to come with respect to Tymoshenko. At the very least, such a gesture would have won the Yanukovych regime a bit more time and breathing space.

Instead, the Yanukovych people decided to act against their own interests. Having shot themselves in one foot with Tymoshenko, they proceeded to shoot themselves in the other foot with Lutsenko. Not accidentally—but purposefully, after carefully taking aim and pulling the trigger.

Such suicidal behavior bespeaks either a complete breakdown of coordination within the regime, or complete incompetence, or complete stupidity. As I've suggested on a number of occasions, all three outcomes are intrinsic features of Sultanistic regimes that centralize too much power in a poor leader.

Tymoshenko commented on Lutsenko's sentencing with the following words:

Their end will come and it will come soon. Their infamous end will not come from abroad, but from within Ukraine: from Lviv and Donetsk, from Odessa and Poltava, from Chernihiv and Kharkiv. Today we are behind bars. But if that is the price we must pay to free the country, then we are willing to pay it. Yuri, I know, will agree with me.... Till we meet again in freedom!

This is the language of martyrs, victims, and heroes. If the Regionnaires weren't so narrow-minded and so dumb, they'd know that, in today's day and age, you can't beat Martin Luther King, Nelson Mandela, or Vaclav Havel. You can imprison them and you kill them, but you can't beat them.

Photo Credit: Влада Ярославська

Alexander J. Motyl's Blog

- Alexander J. Motyl's profile

- 21 followers