Alexander J. Motyl's Blog, page 22

November 28, 2012

Yanukovych and Stalin’s Genocide

Every November Ukraine commemorates the Holodomor, the famine and genocide of 1932 and 1933. Since 2010, President Viktor Yanukovych has marked the occasion with a formal address to the people. Read in isolation, none of them is terribly interesting. A comparative look at all three speeches, however, reveals some interesting shifts in tone and content that may illuminate Yanukovych’s own evolving thinking about the genocide and his regime.

But first a striking continuity. Yanukovych has never called the Holodomor a genocide. He’s called it a crime, a tragedy, and an Armageddon, but not genocide. Ironically, he does use the term Holodomor, which means “killing by means of hunger” and, in that sense, is virtually a synonym for genocide. There are indications that this reluctance to call a spade a spade may change.

Back in 2010, during his first encounter with Holodomor remembrance day, Yanukovych stated (this and subsequent citations are the translations provided on his website):

I bow to the memory of those innocently killed by the Holodomor.

Even now, the tragedy of 1932–1933 is difficult to comprehend. It was a real Armageddon, when people were loosing [sic] their human essence because of hunger.

Therefore, this national tragedy that has devoured millions of innocent people, is no subject to oblivion.

Note the reference to “a real Armageddon” and the “millions of innocent people.” Note as well, however, that Yanukovych treats the Holodomor almost as if it were a natural catastrophe that somehow befell Ukraine. And he can’t resist chiding the Orange government of Viktor Yushchenko for its efforts to commemorate the famine:

However, when these sad commemorations have begun to resemble a conveyor, when at numerous gatherings and round tables some so-called “scientists” have begun throwing around with ease the numbers of those, who died of starvation—3 million—5 million—7 million and even more, it became a blasphemy. After all, even one person’s death is an uncompensated loss not only for the family, but also for the Cosmos. So how can one throw around millions at the abacus as though it is something insignificant? It is an unforgivable sin.

One year later, in 2011, Yanukovych’s speech strikes different tones. For one, it’s much shorter—94 words as opposed to 336 in 2010, when finger-pointing was the order of the day. For another, Yanukovych clearly implies that the famine actually had a political cause: totalitarianism.

Every year, in late November, we pay tribute to the victims of a terrible famine that killed millions of people. The unprecedented tragedy of global scale inflicted an irreparable loss on Ukraine.

Terrible years of totalitarianism have been a spiritual catastrophe: numerous churches were demolished, hundreds of thousands of peasants, workers, and intellectuals were physically eliminated or sent to the Gulag camps, almost every Ukrainian family suffered.

The bravado that characterized the 2010 speech is also gone: after almost two years of power, Yanukovych knew he had little to boast about and ends his speech as follows:

Preserving the sacred memory of our tragic past, the Ukrainian state is confidently moving forward, building civil society on the principles of rights and freedoms, laying a solid foundation for future generations.

In 2012, a further shift is evident. The speech is still short (141 words), but the Holodomor is now a “crime” and crimes always have, as we know, perpetrators. Yanukovych doesn’t say who is responsible and he expands the Holodomor to “other countries of the former USSR,” but the implication is clear: the totalitarian Soviet regime committed the crime.

These days it will turn 80 years since trouble has come to our land.

In the period of 1932–1933, Holodomor covered the territory of Ukraine and other countries of former USSR.

This crime has changed the history of Ukrainian people forever. It has been one of the severest challenges of Ukrainians. Holodomor not only killed people, but also had the purpose of causing fear and obedience. For decades, any mention of those dreadful events has been banned.

No less important, there is no talk of past or present governments and their failures or achievements: after all, by November 2012 Yushchenko is just a memory and the Yanukovych regime is a complete bust. Instead, Yanukovych acts like a politician in serious trouble and praises the people for their fortitude and strength:

But Ukrainian people demonstrated tenacity. Due to belief in its power, love to Ukraine, primordial pursuit of freedom and independence we have survived.

Today, a little candle flame unites us in a prayer for souls of Holodomor victims. We also remember those who shared the last piece of bread and saved lives of compatriots.

Here’s a tentative prediction. If the regime continues to decay at its current rate and if the economy tanks, as it’s very likely to do, Yanukovych will—hold on to your seats!—utter the word genocide in his Holodomor commemorative address of 2013. If he does, you’ll know that he knows his days in power are numbered.

November 19, 2012

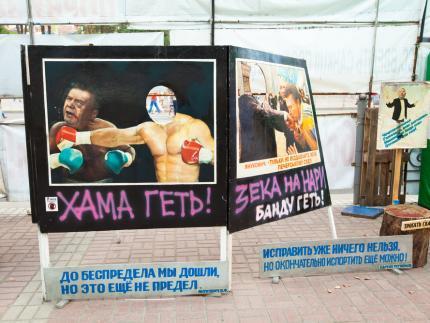

Targeting Ukraine's Corrupt Leaders

A recent policy memo of the European Council on Foreign Relations, “The EU and Ukraine after the 2012 Elections” (pdf), is well worth reading. Its author is Andrew Wilson, senior policy fellow at the council, a reader in Ukrainian studies at the School of Slavonic and East European Studies at University College London, and the author of several highly regarded books on Ukraine.

Wilson begins by reminding us that “Relations between the EU and Ukraine are at an impasse. The last two years have been dominated by rows over the selective prosecution of regime opponents, in particular the conviction of former Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko in October 2011, and an accelerating trend towards a more authoritarian and corrupt style of rule in Ukraine.”

So what should the EU do about Ukraine? The answer, in short, is to embrace its people and squeeze its ruling elites.

Wilson warns that the EU should not “make the conduct of the elections the only criterion for deciding whether or not it should restart relations with Ukraine, or judge the authorities more on past than on present behavior and use a critique of the elections to move towards a de facto isolation policy.”

After all, as tempted as Europe might be to run its back on the regime of Viktor Yanukovych, doing so would only deprive the EU of leverage, do nothing to stem Regionnaire misrule, and wind up punishing the people of Ukraine, and not the authorities.

According to Wilson: “The EU therefore needs to think of creative ways of regaining influence while maintaining red lines on values—not least because the political situation in Ukraine could easily deteriorate further…. The authorities are entrenching themselves in power by every possible means, and members of the literal and metaphorical ‘family’ around President Yanukovych are using that power to enrich themselves on an unprecedented scale. The EU cannot afford to wait until the next contest in 2015.”

So what, specifically, should the EU do? Wilson makes the following suggestions:

First, Europe needs to speak with one voice—which is another way of saying that Europe needs to have one clearly articulated position on Ukraine and stick to it. As long as Berlin says one thing, Brussels another, and Paris still another, the Regionnaires will be able to talk out of both sides of their mouths and avoid giving clear answers.

Second, Wilson recommends the “provisional application” of the Association Agreement and the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement with Ukraine: “the agreements … will help transform Ukrainian society in the long run…. But it makes little sense to block the agreements to punish Ukraine. Rather, the EU should take a tougher line in other areas in order to allow the agreements to be revived.”

Just what kind of tougher line?

“The resolution on Ukraine passed by the US Senate in September [2012] is the beginning of a trend towards the construction of a Ukrainian equivalent of the ‘Magnitsky List.’ The European Commission is investigating Gazprom. The EU should start with a visa ban on Renat Kuzmin, the deputy prosecutor responsible for the trials of Tymoshenko and former Interior Minister Yuriy Lutsenko.”

A visa ban on odious individuals would be nice, but hitting ’em where it hurts—their pocket books—would, of course, be better.

“The EU should also audit the activities of suspect ‘family’ companies in Austria, Cyprus and Luxembourg (and in Liechtenstein and Switzerland), which break existing EU law. This need not be formal ‘sanctions’; it can be undertaken by national financial security agencies. The US is currently taking a tougher line, but most of the Ukrainian elite’s financial malfeasance is within the EU and dependencies like the British Virgin Islands. For example, the Activ Solar company, which is based in Vienna, allegedly acts as a front for government circles that are siphoning off budget money and circulating it back home tax free.”

A Ukrainian friend suggests a more refined version of hitting the elites where it hurts: the EU and the US should publicly roll out an entire program of sanctions entailing travel bans and wealth confiscations along with specific demands and deadlines. Each set of sanctions would reach higher up the food chain and effectively tighten the noose around the president, while giving him both time and reason to stop the process. Thus, the first step might be to ban the abovementioned Kuzmin and his entire family from traveling to the West unless Tymoshenko and Lutsenko are released in, say, two months. If nothing happens, the second step might be to ban Kuzmin’s boss and a raft of other individuals within the Justice Ministry and Procuracy. Third on the list might be Prime Minister Mykola Azarov, whose son leads a lavish lifestyle in Vienna. Fourth might be Viktor Yanukovych’s two sons. And so on, until, months on, it would be the president’s turn. By then, Yanukovych might realize that the West is serious, that sanctions hurt, and that all can be made well by dismantling the sultanate and restoring democracy and the free market.

Third, says Wilson, the EU should pursue visa liberalization for Ukrainians. “Ratification by the European Parliament of the new amended Visa Facilitation Agreement signed in July has also been blocked because of the Tymoshenko affair, but should now move forward.… Wider travel will liberalize Ukraine in the long run.”

Naturally, nothing would annoy the Regionnaires so much as seeing that the ordinary folk have the privileges they now lack. What’s the point of being a crook if you can’t flash your Rolex watch in Paree?

In the end, Wilson concludes, “Ukraine’s leaders behave like they have immunity and impunity, as if Ukraine were a vital raw material supplier or possessed of other geopolitical importance. In reality, they only have power in isolation. The EU should not fear continuing to apply tough standards to Ukraine. But the EU needs leverage and should also work harder to show it is on the side of Ukraine’s beleaguered democratic, liberal and economically constructive forces. Once Ukraine develops proper relations with Europe appropriate to its size, location and economic potential, the EU’s leverage will be much higher. It’s time to show Ukraine some tough love.”

Hear, hear! Except for one thing: you can’t love gangsters and thugs. You can only be tough with them. As to love, reserve that for the people.

November 15, 2012

Ukraine’s Indifference Meets West’s Indifference

What, if anything, will President Obama’s policy toward Ukraine be?

His October 22nd foreign policy debate with Governor Mitt Romney may hold some clues. Naturally, you wouldn’t expect either debater to focus on Ukraine, but it’s still striking just how little attention was paid to Ukraine’s neighborhood—Europe and Russia.

Neither Obama nor Romney mentioned Europe or the European Union, even once. Ditto for Germany. France, the United Kingdom, and Poland got one mention apiece, but only in passing, while Greece got two, but only as a metaphor for a fate that needs to be avoided. Russia was mentioned ten times, mostly in the below exchange:

OBAMA: Governor Romney, I’m glad that you recognize that al-Qaeda is a threat, because a few months ago when you were asked what’s the biggest geopolitical threat facing America, you said Russia, not al-Qaeda; you said Russia, and the 1980s are now calling to ask for their foreign policy back because, you know, the Cold War’s been over for 20 years.

But Governor, when it comes to our foreign policy, you seem to want to import the foreign policies of the 1980s, just like the social policies of the 1950s and the economic policies of the 1920s…. You indicated that we shouldn’t be passing nuclear treaties with Russia despite the fact that 71 senators, Democrats and Republicans, voted for it….

ROMNEY: …First of all, Russia I indicated is a geopolitical foe…. It’s a geopolitical foe, and I said in the same—in the same paragraph I said, and Iran is the greatest national security threat we face. Russia does continue to battle us in the UN time and time again. I have clear eyes on this. I’m not going to wear rose-colored glasses when it comes to Russia, or Mr. Putin. And I’m certainly not going to say to him, I’ll give you more flexibility after the election. After the election, he’ll get more backbone.

Beats me what all this Russia talk amounts to. Perhaps the most we can conclude is that incoherently expressed sentiments may amount to an incoherent policy.

In any case, if the debate is anything like an approximate guide to the foreign policy priorities of the new president, then it’s clear that those are overwhelmingly centered on the Middle East and China. The Middle East was mentioned 23 times, Iran 47, Israel 34, Syria 28, Iraq 22, Afghanistan 21, and Egypt 11. China got 32 mentions.

To be sure, the obsession with the Middle East makes all sorts of sense, both for domestic- and foreign-policy reasons. There is a terrorist threat. The possibility of Iran’s getting the bomb is distressing. Wars are still being waged in Iraq and Afghanistan. Israel’s security is under threat. The Arab Spring has turned out to be more of a winter. Still, you’d think that the possibility of the euro’s collapse or the European Union’s transformation into either a superstate or a super mess would be of some interest to the United States. And you’d also think that Russia, what with all its nukes and oil and gas and Putinist chest-beating, would deserve to be more than a pretext for an incoherent exchange.

Ukraine’s absence is hardly surprising, of course, but it should serve as a reminder to Ukrainian policymakers of their country’s complete and total irrelevance to American, and by extension Western, foreign policy. And the Ukrainians have no one to blame for this sad state but themselves.

Ukraine would matter to the world in general and to the West in particular if it lived up to its economic and political potential. A powerful Ukrainian economy would attract attention. A robust democracy and a clear pro-Western foreign policy would also attract attention. But when thievery replaces economic reform, political repression replaces democracy, and foreign-policy obtuseness replaces foreign-policy astuteness, it’s small wonder that no serious Western country cares about Ukraine. You’ve got to want to matter to the West in order to matter to the West. But the regime of Viktor Yanukovych is far more interested in self-enrichment and coupon-clipping than in statesmanship and good government.

Although the West began experiencing “Ukraine fatigue” in the last years of Orange rule—thanks in no small part to President Viktor Yushchenko’s incomprehensible inability to distinguish between policy making and hating Yulia Tymoshenko—fatigue was at least premised on a recognition of Ukraine as a country that wasn’t living up to its potential. What we see at present is “Ukraine indifference.” And that won’t change as long as the Yanukovych regime suffers from “West indifference” and continues to believe that corruption and authoritarianism are a substitute for legitimacy and democracy.

November 8, 2012

Understanding Ukraine's Ultranationalist Support

What does the ultranationalist “Svoboda” Freedom Party’s 10.5 percent share of the party-list vote in Ukraine’s October 28th parliamentary elections mean? Is it the end of the world? Have Ukrainians embraced fascism and anti-Semitism? Or might there be somewhat less alarmist explanations for Svoboda’s showing?

There are three good explanations—and one shockingly bad one—for Svoboda’s rise from a minor regional party to a very minor national force. After all, let’s not forget that Svoboda received the fewest votes of the five parties that made it into the Parliament.

First, most Ukrainians certainly didn’t vote for Svoboda because they read its program. If they had, they would have noticed that Svoboda’s socioeconomic vision of Ukraine resembles that of the Republican Party for the United States and that its approach to ethnic relations is strikingly similar to official policy in the Baltic states. Nor did Ukrainians vote for Svoboda because they were familiar with its record of governance, which, according to one Lviv-based businessman’s private communication, has been abysmal:

Since 2010, Svoboda has had a majority in the Lviv City Council and is the largest fraction in the Lviv Province Council. I haven’t noticed any important achievements. They wisely choose to stay away from economic issues, preferring to engage in shrill criticism. Their intellectual capacity is weak. Their economic views are naive and primitive, reminiscent of socialism. They’re also corrupt, especially those who came to power recently and had criminal connections in the 1990s. Some businessmen have even been approached by them to pay protection money.

Ukrainians voted for Svoboda because they were fed up: with Regionnaire abuse of them and their culture and with the democratic opposition’s fecklessness. Placing Svoboda in the Parliament promised to put up at least rhetorical barriers to Regionnaire excess. As one Kyivite told me: “The Party of Regions is like the Nazis: they can only be stopped with force.” Or, as political analyst Volodymyr Fesenko, put it: “About 30-40 percent of Svoboda’s supporters are ideological believers in the idea of Ukrainian nationalism. But in Kyiv and central Ukraine many people voted for Svoboda as the most radical force, as the ‘special forces’ of the opposition. By the way, many Russian-speaking women voted for Svoboda.”

Second, Svoboda would never have made it to the national stage in the absence of the profoundly xenophobic, anti-Ukrainian, and Russian supremacist policies pursued by the Yanukovych government since early 2010. Regionnaire radicalism thus made the growth of ultranationalist radicalism both possible and inevitable. Indeed, there are good reasons to believe that the Regionnaires understood that their policies would benefit the ultranationalists. When President Yanukovych appointed Dmitri Tabachnik, a notorious Ukrainophobe, as minister of education, he had to know he was insulting all Ukrainians. When Yanukovych refused to fire Tabachnik even after a series of firestorms broke out over his anti-Ukrainians remarks, he knew full well that he was rubbing salt into old wounds. When, finally, the Yanukovych regime approved the openly anti-Ukrainian Law on Languages last summer, it understood that it was purposely dividing the country and adding fuel to the ultranationalist fire. Given this record of extremism, it is morally obtuse for critics of Svoboda’s xenophobia to refrain from criticizing Regionnaire (as well as Communist) Ukrainophobia.

Third, Ukraine’s primarily Russian-speaking, pro-Regionnaire oligarchs have actively supported the Freedom Party. Viewers of Ukrainian television know that for the last few years Svoboda firebrands have been unusually frequent guests on the country’s two most popular talk shows moderated by Russian journalists Yevgenii Kiselov and Savik Shuster, both of which are aired on oligarch-funded and regime-friendly television stations. There’s also been a nagging rumor that the Regionnaires and some oligarchs have funneled money to Svoboda (a charge Svoboda denies). A reliable source who spoke with a high-ranking government minister two years ago was told the following: “The Party of Regions used to support Svoboda. Then Kolomoisky did and now I don’t know who.” Kolomoisky, by the way, is Igor Kolomoisky, a Dnipropetrovsk-based oligarch who also happens to be the president of the United Jewish Community of Ukraine. Just why Kolomoisky stated in 2010 that “Svoboda has clearly moved from ultranationalism closer to the center and has become more moderate” is unclear: did he believe what he was saying or was he just trying to enhance its respectability as part of some murky game?

Why would the Regionnaires and oligarchs support Svoboda? The logic is simple, if you remember that the deeply unpopular Yanukovych will not be reelected in 2015 if he runs against a credible democratic candidate. The one person he would, as the lesser of two evils, definitely be able to beat is Svoboda’s head, Oleh Tyahnybok. Here’s the liberal Lviv-based intellectual Taras Voznyak’s analysis: “It’s clear that Tyahnybok will not receive 50%-plus-one votes throughout all of Ukraine…. That’s why he’s safe for Yanukovych. But in order to bring Tyahnybok into the second round of the presidential elections, he must be made, if not the leader, then one of the equally prominent leaders of the opposition. And for that he needs to have a substantive representation in the Parliament.”

According to Voznyak, it’s not just Yanukovych who needs Svoboda. It’s also the oligarchs:

The existing Ukrainian state is the best possible country for the Ukrainian oligarchate. The oligarchs have done extremely well in this country and they will continue to do so. They can pillage no less well under a blue-and-yellow flag and trident as under a red flag and hammer and sickle; that’s not important. It’s their country and they really live here, while the people just survive. Hence: no integration into the European Union! No to Russia! Our oligarchs are the greatest supporters of independence: they want to and will pillage Ukraine on their own.

In sum, Svoboda’s rise is overwhelmingly due to Ukrainian anger at the Yanukovych regime, anti-Ukrainian Regionnaire radicalism, and Regionnaire-oligarch connivance. It follows that the best antidote to Svoboda is, quite simply, democracy, rule of law, and the free market in general and the dismantling of the Regionnaire “oligarchate” in particular.

Here’s a shockingly bad explanation for Svoboda’s rise offered by the Jerusalem Post: “Historically, Ukrainian anti-Semitism is legend for its crudity, ferocity and intrinsicality. The Ukraine’s reputation for ongoing racism and ever-virulent intolerance is equally well-earned. Jew-revulsion never quite went out of fashion among broad segments of the population there. So it was not too shocking to learn last week that the extreme nationalist Svoboda (Freedom) party’s fortunes had risen dramatically in the recent elections and that it now controls 41 out of the parliament’s 450 seats.”

In other words, Ukrainians are “intrinsically”—that is, innately—anti-Semitic brutes. Needless to say, ascribing “intrinsically” negative qualities to entire peoples is racist and, as such, no less repugnant than claiming that African-Americans are innately prone to violence, that Jews are innately prone to usury, or that women are innately prone to hysteria. Naturally, if you do believe Ukrainians are savages by birth, there’s only one way to keep their “crudity, ferocity and intrinsicality” in check: by violence. And, not illogically, the Post concludes with a backhanded endorsement of Stalinism: “anti-Semitism … in Ukraine … is vulgar and in-your-face—as it was before the Soviets temporarily held the genie in the bottle.”

True, totalitarianism can destroy any genie, but suggesting that the Soviets’ “temporary” use of genocide, terror, and the Gulag is the appropriate response to a marginal party’s marginal success at the polls may be just a tad extreme—and extremist.

Photo Credit: Vasyl Babych

November 1, 2012

After Ukraine's Elections, What's Next?

The parliamentary elections are over and—surprise!—the Regionnaires won, as they and everybody else in Ukraine knew they would, despite the fact that they are deeply unpopular and would, in a fully fair and free election, have suffered an embarrassing defeat. But if you have the money, you can buy as many votes as you need, which the Regionnaires did with wild abandon. If you control the electoral committees, you can make sure the vote count is just right. And because half of the deputies were now elected in first-past-the-post majoritarian districts, the Regionnaires will be able to do what they do best: buy them and their votes at several million dollars a pop, which of course is pocket change for Viktor Yanukovych’s corrupt party. With an estimated 188 deputies, the Regionnaires will have ten fewer deputies than they had before, but still hold a plurality of the total (450).

Somewhat more surprising is the distribution of deputies among the non-Regionnaire parties. The Fatherland party of former Foreign Minister Arsenii Yatseniuk and imprisoned former Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko will have 103 deputies. Boxer-turned-politician Vitalii Klitschko’s Ukrainian Democratic Alliance for Reform will have 40. The Communist Party of Ukraine, headed by multimillionaire Petro Symonenko, will have 32, and the right-wing Freedom Party of the charismatic Svengali, Oleh Tyahnybok, will have 37. (These were the figures after 98.82 percent of the votes were counted.)

The Regionnaires, the Communists, and the Svobodites are all radical parties, but with different twists. Yanukovych’s pals are radicals in deed, but not in word: they talk moderation, but dismantled democracy, assaulted Ukrainian identity, and impoverished the population in a little under two years—an impressive achievement for any wild-eyed revolutionary. The Communists are radicals in past deeds and in present word: they helped build “mature socialism” but are now gray-haired Stalinists who talk “proletarian dictatorship” but prefer to ride in plush limousines. The Svobodites are radicals in word—they say they wish to enthrone ethnic Ukrainians atop the multinational Ukrainian state—but not in deed: in the few areas of western Ukraine where they’ve run local councils, they’ve proven themselves to be incompetent blowhards with a penchant for corruption.

Remember: Regionnaire radicalism made the impressive growth of both Communists and Svobodites possible. Until recently, the CPU seemed like it was going to join the “garbage heap of history,” as the Soviets used to put it. And Svoboda seemed fated never to exceed the 5-percent barrier and remain a regional party in some western Ukrainian districts. Once the Regionnaires went on the attack, however, it was inevitable that there would be an equivalent counter-attack by political forces claiming to defend the two constituencies the Regionnaires have dissed the most: all workers and all Ukrainians.

The result is a radicalized electorate. If you think of the party-list vote as reflecting general popular attitudes, then more than half of the population supports radicals: 30 percent went for the Regionnaires, 13 percent for the Communists, and 10 percent for the Svobodites. Real or faux radicalism will not make the Ukrainian Parliament a more stable, measured, and reasonable place. Quite the contrary, expect the clash of radical rhetoric to intensify and the institution to become fully dysfunctional. That means that the burden of Regionnaire misrule will now fall fully on poor Viktor Yanukovych’s shoulders. The sultan will have to plunder and mismanage the country completely on his own, which means that the blame for anything that happens (and there’s almost certainly not going to be any praise) will fall on him as well. His prospects for winning the 2015 presidential elections will dim accordingly.

But there is more potentially good news. Despite the prolonged extremist assault by Yanukovych and his merry band of Regionnaires, about 40 percent of the electorate did vote for democratic parties (Fatherland and UDAR). That’s less than the entire radical share of the vote, but it’s more than any of the radical alternatives. That matters because it may now be possible for the democrats to outwit the radicals. It’s hard to imagine just how the Regionnaires could consistently rule together with the Communists. The two sides can agree on discriminating against Ukrainian language, culture, and identity, but—despite the Communist elites’ love of fast women and fine wines—the two will have difficulty agreeing on a socio-economic program. After all, the Regionnaires favor the oligarchs and themselves. The Communists say they support the proletariat and their claims will constrain their ability to become left-wing Regionnaires. If the democrats play their cards right—a very big if—they just might be able to play the Regionnaires against the Commies.

It’ll be easier for the democrats to play off the Svobodites against both Regionnaires and Communists. Despite their fire-breathing rhetoric, the Svobodites who run local governments have turned out to be mediocrities. They have not, as democrats feared they might, discriminated against minorities, promoted “fascism,” incited ethnic animosities, and the like. If their bark is indeed worse than their bite, the Svobodites might at key moments be brought into situational alliances with the democrats that could keep Ukraine from sliding further into the grip of Regionnaire radicalism and misrule.

All of which means that, with a little bit of luck, the democrats will be able to use the dysfunctional Parliament as a base from which to project some influence and prepare for the 2015 elections. If they could then agree on a single candidate—say, Tymoshenko or Klitschko—who knows? They might even win and end the Yanukovych Era.

October 25, 2012

Yanukovych after the Fall

What will Viktor Yanukovych do after he falls from power?

That’s a question that should concern Ukraine’s current president, especially as Ukrainians are preparing to go to the polls on October 28th. After all, just about everyone in Ukraine hates him: from the regular folk to the intellectuals to the elites to his supposed supporters. It didn’t have to be that way. Even a half-hearted commitment to reform and good government would have won him accolades. Since it’s too late to save his ruined presidency, there’s nothing left to do but wait for it to end.

And sooner or later end it will. It could happen in 2015, if the oligarchs who back him decide he’s a loser and send him to the showers. It could happen in 2020, after his second term is up and Ukraine has been devastated so thoroughly that no one in the country—not even well-fed Regionnaires—will want him around. It could happen between now and 2020, if some Regionnaire cabal decides that his incompetence has gotten to the point of undermining their privileged status or if the people realize that the prospect of endless Regionnaire rapine is no way to live one’s life and chase poor Viktor out of the presidential palace. Or it could happen anytime Yanukovych’s health begins to crumble under the pressure of too many late nights.

After all, although Yanukovych the man may not believe it now, he’s just human and humans have been known to suffer from creeping mortality. And although Yanukovych the president certainly can’t envision the end of his presidency—what aspiring tin-pot dictator doesn’t dream of misruling forever?—that presidency will end. Presidencies always do, even good ones, and Viktor, like his role models Vladimir Putin of Russia and Aleksandr Lukashenko of Belarus, will someday just be a bad memory

Were Viktor a bit more inclined to pick up an occasional book, he’d do well to read up on Poland. He might notice that independent Ukraine, which is supposed to resemble post-Communist Poland, actually resembles Communist Poland. Ukraine’s independence in 1991 was pretty much a repeat of Poland’s abandonment of Stalinism in 1956. Ukraine’s first two presidents, Leonid Kravchuk and Leonid Kuchma, are strikingly similar to Poland’s Communist leaders, Stanislaw Gomulka and Edward Gierek. The Orange Revolution of 2004 was virtually identical to Solidarity’s revolution of 1980–1981.

Which means that the man who crushed Solidarity, General Wojciech Jaruzelski, is none other than Viktor Fedorovych Yanukovych himself.

Jaruzelski was incapable of doing anything but cracking down on the democratic opposition. Poland stagnated, regime legitimacy declined, and the ruling Communist Party decayed. Similarly, Yanukovych is incapable of doing anything but cracking down on the democratic opposition. Ukraine is stagnating, regime legitimacy is declining, and the ruling Party of Regions is decaying.

When 1989 came along, the Jaruzelski regime was exposed as a house of cards, and the collective efforts of the opposition and population brought it down in a matter of days. Ukraine’s 1989 will also come and, when it does, the Regionnaires will head for the hills and Yanukovych will become a pariah.

Where will the Regionnaires go? Their wealth is in Western Europe and the United States, but it’s unlikely that any Western democracy will open its doors to thousands of crooks. Russia and Belarus might welcome some of them, but will they want a mass influx of embittered and impoverished Regionnaire schemers? Probably not. That leaves such offshore havens as the Cayman Islands. Keep that in mind when you’re planning your vacation a few years from now.

And how about ex-president Yanukovych?

If Putin’s still in charge, Russia won’t be an option, since Vlad famously detests Vik. Minsk might work, but who wants to live in what Lukashenko proudly called Europe’s last dictatorship? Either way, Yanukovych would have to say good-bye to all the goodies his family has squirreled away in the West. And besides, the West is likely to put him and his sons on some black list anyway, so forget the Riviera or Palm Beach.

Which leaves three options: the first is some pariah state, such as North Korea (too cold), Zimbabwe (too hot), or Somalia (too dangerous). The second is to try to make it to the South Pacific on his Spanish-style Galleon (too leaky). The third is to stay in Ukraine and face the music. He’ll have to do it on his own, of course, as all his erstwhile yes-men will publicly denounce him and claim that they had secretly supported democracy all along.

At a minimum, some future democratic Ukrainian court will strip him and his sons of all their assets. Will the former president then get a job as a security guard at some Donetsk coal mine? At a maximum, the court will put him in jail, and, if the judges have a sense of humor, they’ll also do so on the same grounds as Yanukovych’s imprisonment of opposition leader Yulia Tymoshenko.

Viktor Fedorovych may then take some consolation from the poetry of it all. His political career will have ended in the same place it began.

October 18, 2012

Genocide's Definition Revisited

If you think you know what Raphael Lemkin, the originator of the term genocide, thought about genocide, think again. A dissertation-in-progress on Lemkin and the history of the United Nations Genocide Convention by Douglas Irvin-Erickson, a doctoral student in global affairs at Rutgers University-Newark, is likely to change how we think and talk about genocide.

As Irvin-Erickson writes in an article (“The Romantic Signature of Raphael Lemkin”) scheduled to appear in the Journal of Genocide Research:

Lemkin used the work of an art historian to define nations as “families of minds”…. Lemkin intended the word genocide to signify the cultural destruction of peoples, which could occur without a perpetrator employing violence at all. In his 1944 Axis Rule in Occupied Europe, Lemkin wrote that genocide was “a coordinated plan of different actions aiming at the destruction of essential foundations of the life of national groups, with the aim of annihilating the groups themselves.” A colonial practice, genocide had two phases: “One, the destruction of the national pattern of the oppressed group; the other, the imposition of the national pattern of the oppressor.”

Genocide, in other words, is not, in Lemkin’s understanding, about mass killing per se, but about the destruction of nations qua nations. Mass killing is, thus, a means to the end of genocide, and not its goal.

Lemkin adopted his definition of a nation as a family of minds in the context of his writing on the French genocide against Algeria, where he believed that the French colonial power was breaking the “bodily and mental integrity” of the Algerian people.… The goal of the genocide, Lemkin wrote, was to integrate Algerians into the French Republic and prevent Algeria from emerging from colonial rule.

Keep in mind that here, too, genocide for Lemkin is not the bloody and brutal war fought between France and the Algerians in the 1950s and early 1960s, but the entire French colonial project that attempted to destroy the Algerian “family of mind.”

Lemkin believed the political regimes led by Hitler and Stalin both committed genocide…. [T]hese two regimes shared the defining characteristic of attempting to destroy the national patterns of the oppressed groups and replace it with a “Sovietness” or “Germanness.” Lemkin argued that the Russian and Soviet attack on the Ukrainians, Poles, Hungarians, Romanians, Jews, the Crimean and Tatar Republics, the Baltic nations of Lithuania, Estonia and Latvia, and the total annihilation of the Ingerian nation, were all genocides, before and during Stalin’s reign.

Genocide, Lemkin asserted, was a long-term element of the Kremlin’s internal policy and “an indispensable step in the process of ‘union’ that the Soviet leaders fondly hope will produce the ‘Soviet Man,’ the ‘Soviet Nation.’” Just as the Nazi genocide sought to eradicate the national patterns of the occupied territories and install a distinct “Germanness” to consolidate state control, “the leaders of the Kremlin will gladly destroy the nations and the cultures that have long inhabited Eastern Europe.” The Ukrainian genocide was “an essential part of the Soviet program for expansion, for it offers the quick way of bringing unity out of the diversity of cultures and nations that constitute the Soviet Empire.”

It follows from the above that, according to Lemkin, the Holodomor—the famine of 1932-1933—was only one of the means employed by the Stalinist regime to Sovietize and Russify the Ukrainian nation. The actual genocide was Sovietization and Russification, processes that were initiated during the Civil War of 1918-1921, revived by Stalin in the late 1920s, and then vigorously pursued by him and all his successors, including Nikita Khrushchev and Leonid Brezhnev, into the early 1980s. It was only under the liberalizing rule of Mikhail Gorbachev that the Russificationist project, and hence genocide, was abandoned.

The genocide was not that Stalin’s regime killed so many people, but that these individuals were killed with the purpose of destroying the Ukrainian way of life, an argument in line with his writings on how the French colonial state sought to eradicate Algerian national consciousness through state terror, political disenfranchisement, and poverty.… The most devastating aspect of the genocide for Lemkin was not the death of individuals, but the potential loss of a cohesive group who shared a common belief in their unity through language, customs, art, or even a sense of shared history.

Irvin-Erickson here raises the intriguing possibility that the cultural policies of the current Yanukovych regime would qualify as genocidal in Lemkin’s eyes. After all, there is little doubt that their purpose is: “One, the destruction of the national pattern of the oppressed group; the other, the imposition of the national pattern of the oppressor.” In this case, “the Ukrainian way of life” would, in the Yanukovych regime’s scheme of things, be replaced with the “Donbas pattern of the oppressor”—a way of life that is Soviet, criminal, and Lumpen-Russian. As the pesky Ukrainian “family of mind” gives way to a “family” of, as Czeslaw Milosz might have put it, “captive minds,” what’s left of Ukrainians as a “cohesive group who shared a common belief in their unity through language, customs, art, or even a sense of shared history”?

Naturally, you needn’t reach this conclusion—but only if you disagree with Lemkin’s views on genocide.

October 11, 2012

Real Men and Women in Ukraine

If you’ve seen Joseph von Sternberg’s 1930 classic film The Blue Angel, you’ll know that it features the young Marlene Dietrich as the sexy chanteuse Lola-Lola who belts out a song that made her a star: “Kinder, heute abend, da such ich mir was aus.” Lola starts by saying she’s “in love with a man, but doesn’t know which one,” and then proceeds with the refrain:

Hey, kids, tonight I’m gonna find me

A man, a real man!

Hey, kids, I’m fed up with the boys,

A man, a real man!

A man whose heart still burns

A man whose eyes glow with fire

In short: a man who wants to kiss and can

A man, a real man!

Well, I’ve got good news for Marlene. If she were living in Ukraine today, she’d have no trouble finding a real man—or, for that matter, a real woman.

In early September of this year, the “Rating” Sociological Group asked 1,200 Ukrainians, 18 and older, who they believed was a “real man” and a “real woman.” The results are encouraging for Ukraine and its political culture.

The top male vote-getters were: ex-boxer and Ukrainian Democratic Alliance for Reform leader Vitaly Klitschko (30.1 percent), his brother, world heavyweight champion Volodymyr Klitschko (9.9), Russian President Vladimir Putin (9.5), Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych (6.3), democratic opposition leader Arsenii Yatseniuk (5.3), and soccer star Andrii Shevchenko (5.1).

Significantly, Vitaly did well across Ukraine, polling 37 percent and 41 percent in the center and west and 21 percent in both south and east. His brother Volodymyr’s numbers were, respectively, 15, 15, 6, and 5 percent. Putin did well in the center (10), south (15), and east (12), and miserably in the west (2). Yanukovych’s numbers for the center, south, east, and west were 8, 6, 7, and 2 percent, while Yatseniuk’s were 8, 1, 3, and 9 percent.

Thirty-five percent of men preferred Vitaly, while 26 percent of women did. The male-female breakdown for the others was: Volodymyr (12, 8), Putin (11, 8), Yanukovych (6, 7), Yatseniuk (3, 7), and Shevchenko (8, 3).

Here’s the good news. Vitaly Klitschko got the most support, not because he’s a sports star—after all, Volodymyr keeps on knocking out his opponents in the ring and Shevchenko is one of Europe’s best football players—but because he’s a self-made man and aspiring politician who also happens to be tall, dark, and handsome. That he’s a democrat probably accounts for his somewhat lower level of support in the south and east, but there, too, a fifth of the population regards him with esteem. Consider as well that the big-fisted Yanukovych is just a sliver above the bespectacled Yatseniuk: clearly some Ukrainians are happy to consider nerds real men. But there’s also some bad news: evidently, 10 to 15 percent of central and southeastern Ukrainians regard Putin and his bare-chested he-man antics with awe. Fortunately, that’s not a lot.

Here’s the better news. Whom do you think most Ukrainians regard as a “real woman”? Some sexy singer? Some traditional homemaker? Not quite.

It’s the democratic opposition firebrand and political prisoner Yulia Tymoshenko, with 24 percent! She garnered 44 percent in the west, 32 in the center, 6 in the south, and 13 in the east; 22 percent of males and 25 percent of females. To be sure, second, third, and fifth on the list are pop singers Sofia Rotaru, Ani Lorak (both Ukrainian), and Alla Pugacheva (Russian): 10.4, 6.2, and 4.9 percent, respectively. However, fourth and sixth are German Chancellor Angela Merkel (5.2) and former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher (4.2).

In sum, about a third of Ukrainians view really tough, smart, and successful ladies as “real women,” 15 percent admire the mature professionals Rotaru and Pugacheva, and only about a twentieth opted for the Lola-Lola type.

This is great news. Despite having a political culture that is still hostage to too many of the retrograde values that Communism promoted, Ukrainians clearly are breaking out of traditional male-female stereotypes. Vitaly Klitschko is a cross between US basketball star-turned-senator Bill Bradley and bodybuilder-turned-governor Arnold Schwarzenegger. And Yulia Tymoshenko is Ukraine’s answer to an amalgam of Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and businesswoman Carly Fiorina.

A Tymoshenko-Klitschko ticket, anyone? How could Yanukovych, or any Regionnaire for that matter, possibly compete with her burning heart and his glowing eyes?

October 4, 2012

Seeing Ukrainian Socialist Realism

If you’re in New York, go see the Ukrainian Institute of America’s “Ukrainian Socialist Realism” exhibit, which opened on September 14th. The Soviet-era paintings from the Collection of Jurii Maniichuk and Rose Brady will force you to consider some tough questions.

Socialist realism is an intrinsically controversial art form, having been adopted and imposed by Joseph Stalin in the 1930s and surviving in one form or other until the mid-1980s, when Mikhail Gorbachev abandoned most official strictures on the arts. Although socialist realism resembles traditional 19th-century realism and has roots in both Ukrainian and Russian artistic traditions, it also resembles the art of other totalitarian states, such as Nazi Germany, Communist China, North Korea, and the socialist satellites of East Central Europe. Happy, healthy, and exceptionally well-groomed peasants and workers abound, almost invariably in heroic poses. Leaders usually have visionary expressions, pointing to the future and smiling at the adoring masses.

It’s hard not to feel unease viewing paintings that were part and parcel of the self-promotional ethos of what may be the most murderous regime of the 20th century. It becomes doubly hard not to feel unease when one considers that socialist-realist painters made conscious choices to collaborate with such a regime, very often to the detriment of the non-conformists who refused to go along and paid for their stubbornness with their lives. Those who cringe upon viewing socialist-realist paintings may be excused: their doubts are no different from those of Israelis who cannot listen to Richard Wagner’s music, or Germans who refuse to consider Adolf Hitler’s watercolors as art.

And yet it’s equally hard not to conclude that socialist realism is a legitimate form of realism, and that many of the works produced by socialist realists were of high artistic quality, possessing a variety of laudable formalistic qualities on the one hand and being bereft of all too obvious propaganda on the other. Indeed, the distinction between art and propaganda is at best overdrawn and at worst false. Artists have historically promoted the cause of the state, the church, or the rich, being more than happy to draw hefty honoraria from institutions and individuals with morally dubious qualities. The bottom line is that art can be propaganda and propaganda can be art. Moreover, the fact that artists themselves are often odious does not detract from the quality of their work. Few would suggest that T.S. Eliot’s anti-Semitism or Ezra Pound’s fascism or Mykola Khvylovy’s Bolshevism or Ernst Jünger’s proto-Nazism disqualifies these men from the status of great poets or writers.

Indeed, as Lyudmyla Lysenko of Kyiv’s Academy of Art and Architecture pointed out, seeing Ukrainian socialist-realist art out of context—not in Ukraine’s museums, but thousands of miles away, on 79th Street and Fifth Avenue—was a jarring experience for her. Understandably so, as “decontextualization” inevitably transforms the paintings themselves from manifestations of the cultural policy of Stalin and his successors to examples of a particular artistic genre that resembles those a few blocks away in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Context therefore matters: where we see art affects how we see it. And who sees it also affects how it will be seen. And while a Ukrainian-American audience is unlikely to be sympathetic to socialism in any of its guises, it is by the same token less burdened by the specifically Soviet past that afflicts Ukrainians in Ukraine.

Whatever one’s take on socialist realism as art, it’s unquestionably the case that the subgenre constitutes a large part of modern Ukrainian history and culture. Some may laud that fact, others may bemoan it, but everyone must, for better or for worse, recognize it. The challenge for Ukrainians everywhere is to imagine Ukrainian history and culture as consisting, as they obviously did, of Communism and anti-Communism, collaboration and opposition, villainy and heroism—as well as everything in between. Reconciling such irreconcilables may very well be a project that can succeed only with the passage of much time and the emergence of new generations unfettered by the past. After all, how long did it take for the American North and South to find something resembling a common narrative? Or for whites and blacks to do the same?

The American experience suggests that the coexistence of irreconcilables, even after one side’s defeat in war, eventually leads to reconciliation. Germany’s experience suggests that irreconcilables can be reconciled only if one of the options—totalitarianism—is condemned and suppressed. Spain’s experience suggests that reconciliation can work, more or less, if one of the options—fascism—is forgotten.

Ukraine’s three main regions appear to have taken these divergent routes. The Center wants totalitarianism and its opposite to coexist. The West has condemned and suppressed Communist totalitarianism. The East has forgotten the horrors of Communist totalitarianism.

Which approach is best? America, Germany, and Spain are all decent places and their experience may mean that all three approaches can work—eventually. Perhaps that’s the good news for Ukraine: that, given enough time and perturbations, decency will in fact triumph. Of course, given too much time and too many perturbations, there may be no one around to enjoy the victory.

Photo Credit: RIA Novosti archive, image #21733 / Zelma / CC-BY-SA 3.0

September 30, 2012

In Image War, Tymoshenko Bests Yanukovych

The image war between President Viktor Yanukovych and imprisoned former Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko continues.

Ukraine’s hapless leader suffered another knock-down punch on September 29th, when the online press published two sets of contrasting images: a video of the imprisoned Tymoshenko enjoining Ukrainians not to submit to dictatorship and a series of photos of Yanukovych’s lavish digs. Tymoshenko comes across as impassioned, brave, and principled. Yanukovych comes across as a spoiled brat with megalomaniacal fantasies of ruling over Never-Never Land.

She calls Ukraine “a criminal country built by Yanukovych.” As far as human rights are concerned, “the Yanukovych mafia has no regard for the law. They care only about self-enrichment and corruption.” Who could disagree?

As to herself, Ukraine’s most prominent political prisoner says, “Everyday not only do they exert psychological and physical pressure, but they also transform, consciously and purposefully, every day into hell. And this is Yanukovych’s design.” And even if it isn’t his design, it’s certainly his responsibility.

What’s next for Ukraine? “Either people will rise up and overthrow this criminal grouping at the elections or [this grouping] will treat everyone in its possession, every person, just as they treat me.”

And if Ukrainians don’t heed her advice? “If you don’t immediately realize that Ukraine is run by criminals, by the mafia, then nothing will be able to protect you from the goings-on led by Yanukovych.”

Who could disagree?

While Tymoshenko is progressively becoming Ukraine’s Nelson Mandela, Yanukovych seems determined to become its Nero.

Ukrainska Pravda, an online democratic newspaper, managed to acquire several clandestinely taken photographs of the president’s palatial residence north of the capital city. As it turns out, the plantation-style building Yanukovych let some journalists view last year was just a temporary abode. The real residence is a bona fide palace set within a palatial compound. As befits a Regionnaire with questionable taste, everything is in marble, and no inch appears to be spared some excessively florid design. Yanukovych even has columns on the inside of his abode, and they’re some weird combination of Ionic plus Corinthian styles.

It all amounts to a nightmarish amalgam of nouveau riche kitsch, late Ottoman excess, Disneyland vulgarity, and Donald Trump tastelessness. I’ve often stated that Yanukovych has constructed a highly personalized, authoritarian “sultanistic” regime and that he himself is a sultan. I’m proud to report that Ukraine’s president obviously agrees. No one but a self-styled Donetsk sultan could possibly have concocted something this awful. And no one but a historically ignorant sultan would be imitating a regime that went up in flames.

Having suffered a knockdown punch, Yanukovych must have decided to strike back with Tymoshenko’s own methods: a video of her banging on a prison hospital door, trying to get access to her visitors.

As the accompanying prison press service put it, Tymoshenko, “violating the prison regime and civic order and ignoring the requests of medical personnel not to violate peace in the medical facility as well as all the comments and requests of the Kachaniv prison personnel, attempted to damage the door in a section of the hospital with her heels.”

The bit about “civic order” in, of all places, a Ukrainian prison is just too precious. And just imagine how downright evil Tymoshenko must be to take off her shoe and bang on a metal door. Dang, you can just imagine what must’ve been going through Viktor’s head when he saw the video: No way am I ever letting that broad into my house!

Of course, the actual effect of this video is just the opposite of its intended effect. Once again, Tymoshenko looks determined, while the regime looks stupid.

A Ukrainian friend of mine, a professor, thinks that Tymoshenko may be released after the October 28th parliamentary elections. His reasoning is that things have gotten so bad for the regime that they have to do something to save face. Could be. On the other hand, such a move would require lots of guts, a bit of intelligence, and some minimal appreciation of reality.

The emperor Nero supposedly fiddled while Rome burned. Well, at least he saw that it was burning, while deciding not to do anything about it.

Is Ukraine’s sultan even aware that his regime is burning? The columns in his palace suggest that the answer is no.

Alexander J. Motyl's Blog

- Alexander J. Motyl's profile

- 21 followers