Alexander J. Motyl's Blog, page 13

July 16, 2014

What’s Rong with Wrussia?

Everything, according to some. Many things, according to others. Nothing, according to many Russians.

Back in 2004, two US academics, Andrei Shleifer and Daniel Treisman, wrote a controversial piece for Foreign Affairs in which they argued that statistics proved that Russia was a “normal country.” Since they focused on mostly economic parameters, such as GDP, income distribution, and the like, they had a point.

What Shleifer and Treisman overlooked was the politics. Do “normal” countries normally invade their neighbors, lop off bits and pieces of foreign territory, support unconstitutionally elected, power-obsessed strongman leaders, distrust the world and continually whine about their lost glory, take the crudest Goebbelsian government propaganda at face value, export terrorism, call democrats fascists and fascists democrats, and approve of profoundly corrupt, deeply inefficient, hyper-chauvinist, and blatantly imperialist fascist states?

In a word, what’s rong with Wrussia is not that it’s backward, but that it’s got so many important things backwards.

The depth of one’s pessimism about Russia is largely a function of which part of that long-suffering country strikes you as irredeemably wrong.

If you think Vladimir Putin is the problem, you’re actually an optimist. After all, if all that’s rong with Wrussia is Putin, then his departure—which even his acolytes must agree is inevitable—will solve Wrussia’s problems. Naturally, if, like Patrick Buchanan, Stephen F. Cohen, Gerhard Schröder, Aleksandr Dugin, and Marine Le Pen, you think Vlad is the cat’s pajamas, then nothing’s wrong with the place and we can all sleep soundly.

If you believe the system Putin built—or, possibly, the system that spawned Putin—is the problem, then you’re well on the way to being a pessimist, though not yet of a hopeless kind. I call that system fascist, because, while possessing all the features of run-of-the-mill authoritarian regimes, it also has a charismatic, hyper-masculine strongman leader who employs chauvinism, supremacism, and imperialism as means of reaching out to the public and underpinning his own legitimacy. If the term, fascist, bothers you, fine: call it something else. Call Russia a Putinist authoritarian dictatorship. Call it democratic populist authoritarian. Call it a hyper-managed hybrid post-democratic democracy. Go to town with the modifiers that make you feel better. Just remember that, whatever you call it, it walks and talks like the systems built by Mussolini in Italy and Hitler in Germany.

If the system is what’s rong with Wrussia, then Putin’s inevitable departure, whether from life or from politics, may not change it—or, possibly, it may only transform it into a run-of-the-mill authoritarian regime. Would such a Russia be less inclined to act like a bully internally and externally? Probably not, at least in the short run. Will such a regime outlive Putin? Quite possibly yes.

It’s at this point of any analysis that the depth of one’s pessimism about Russia is tested. If you think that the real problem with Russia is neither Putin nor the house he built, but the Russian people—or, more precisely, their political culture, which, as many Russians and non-Russians argue, is authoritarian and, thus, can countenance only dictatorial rule—then your pessimism is pretty much hopeless. Can Russian political culture change? Sure. But it’s in the nature of culture to change slowly—which means that Russians have the fascist system and the fascist ruler they “deserve.” Even if the ruler goes and the system collapses, both will likely be succeeded by stable authoritarian variants.

Many Russians, along with Putin, Buchanan, Cohen, Schröder, Dugin, and Le Pen, disagree with this diagnosis. That is to say, they don’t disagree that the ruler, regime, and culture are, er, not quite democratic. They just happen to believe that’s a good thing. To them, all I can say is: If you want to destroy democracy, undermine liberalism, and adopt a paranoid foreign policy that has turned Russia into a rogue state, go right ahead. Just keep your proclivities to yourself and don’t export your ruler, regime, and culture to countries that reject fascism.

Which, obviously, brings me to Ukraine and its neighbors in the “near abroad” (a term that only a Russian imperialist pining for the good ol’ days of empire could love). Like everyone else, they don’t know how Russia will or will not change in the next few years. Unlike everyone else, they have to live next door to this hulking, sulking Cyclops of a country.

What do you do if the guy next door is a loud, rude, vulgar, aggressive, violent, thuggish, and heavy-drinking drug dealer and you can’t move out? You reinforce your wall, install several locks, put metal sheeting on your door, lift weights, practice karate, ignore him—and hang out with those neighbors who don’t have awful habits.

That’s why Ukraine’s signing the Association Agreement with the European Union on June 27th was arguably the most important thing to have happened to the country since independence. It means that Ukraine and Ukrainians may finally be able to live in peace—not immediately, as their neighbor turns up his boorishness in response, but eventually and permanently, once he collapses in a drunken stupor. (Unfortunately, many western Europeans are so hooked on Russian oil that they are willing to sell their ideals for a fix.)

When Wrussia becomes Russia—note the “when”: I believe that Putin and his regime will soon alight the ash heap of history—Ukraine and its neighbors should extend the long-suffering Russian people a helping hand. Until then, they have no choice but to avoid Wrussia and its rongs like the plague.

As former President Leonid Kravchuk put it: “We must learn to live with a country that will permanently engage in provocations…. We can’t change Russia, but we can learn to live together against Russia. There’s no alternative.”

Or as a Russian-speaking Donetsk native recently said about the Russians: “My relatives and I, along with millions of Russian-speaking and Russian people in Ukraine, will never again call you our brothers…. we want to protect ourselves from you with a three-meter-thick wall…”

OG Image: Europe and Central AsiaRussiaUS

Europe and Central AsiaRussiaUS

July 10, 2014

Contradictions Define Kremlin Apologists

According to the conventional wisdom, Vladimir Putin and his Western supporters propagate a uniform message throughout the world. At its most extreme, this view sees Russia as having a formidable propaganda machine that is running roughshod over the Western media and public.

In fact, Putin and his supporters and apologists often disagree. One reason may be that the machine just isn’t as formidable as it’s made out to be. Another may be that the Kremlin’s supporters make mistakes when interpreting or anticipating the frequently contradictory or incomprehensible statements of the Delphic oracle that is Putin. A third may be that they have difficulties bridging the growing gap between reality and Putin’s oftentimes shifting views. The Putinite interpretation—one that I won’t even bother refuting—is that disagreement is the foundation of vigorous democracies such as Putin’s Russia.

Consider three recent texts: Putin’s July 1st speech to the Conference of Russian ambassadors and permanent representatives in Moscow; Andranik Migranyan’s June 28th article in the National Interest; and Katrina vanden Heuvel and Stephen F. Cohen’s May 19th article in the Nation.

Putin is Russia’s unconstitutionally elected president; Migranyan is director of the Institute for Democracy and Cooperation in New York, a Kremlin front; vanden Heuvel, editor of the Nation, and Cohen, her spouse, are Putin’s cheerleaders on the American left.

Before looking at discrepancies, consider the most striking similarity: all four see the current crisis in Ukraine as the product of US intrigues (echoes of Jeane Kirkpatrick’s “Blame America First” speech many years ago).

Putin: “The events provoked in Ukraine became the concentrated expression of the notorious policy of containment.”

Migranyan: “Pushing Kiev towards decisive pro-NATO and pro-EU actions, Washington in effect pushed the country into civil war.”

Vanden Heuvel and Cohen: “the Ukraine crisis was instigated by the West’s attempt, last November, to smuggle the former Soviet republic into NATO.”

What’s missing? Ukraine and Ukrainians, of course. None of the texts sees Ukrainians as agents with a voice: they are marionettes, following the dictates of Washington. That this view is completely at odds with what actually happened on the Maidan should be obvious. Far worse, denying Ukrainians agency and a voice is just an old racist trick. Obviously, blacks wouldn’t have demanded civil rights if some outside agitators hadn’t incited them. The women’s movement? A feminist plot. Ukrainians demonstrating in Kyiv? Stooges of the CIA.

Putin and Migranyan probably can’t see that this is racism. Vanden Heuvel and Cohen, who rightly rail against racism on the pages of the Nation, should know better. Shame on them all.

Now consider the differences between these three texts.

Putin sees NATO as a threat: “In the past 20 years, our partners have been trying to convince Russia of their good intentions, their readiness to jointly develop strategic cooperation. However, at the same time they kept expanding NATO, extending the area under their military and political control ever closer to our borders. And when we rightfully asked: ‘Don’t you find it possible and necessary to discuss this with us?’ they said: ‘No, this is none of your business.’”

So do Vanden Heuvel and Cohen: “twenty years of NATO’s eastward expansion has caused Russia to feel cornered.”

Migranyan disagrees with both Putin and the Nation, arguing that NATO is a failure: “With regard to the Ukrainian crisis, a serious topic of conversation is the net benefit to the West (and to the new countries) of NATO’s inclusion of the Baltic States, Poland, and some Balkan countries. As it turned out, strategists who advocated the endless expansion of NATO never dreamt that it would come at a cost. … In this regard, we need only recall the recent scandalous statement by Polish Foreign Minister Radek Sikorski, who … noted that no matter how much Poland tried to bend to US interests, it would only receive the illusion of security and stability in return. Today, it is clear to all that the strategic line followed by [President] Clinton on Russia and the former Eastern Bloc, as well as a string of strategic decisions by the Bush Jr. administration, were a total failure.”

No less embarrassing is the incoherence of the three texts’ defense of Russia’s Crimean landgrab. Here the authors both agree and disagree.

Putin: “What did our partners expect from us as the developments in Ukraine unfolded? We clearly had no right to abandon the residents of Crimea and Sevastopol to the mercy of nationalist and radical militants; we could not allow our access to the Black Sea to be significantly limited; we could not allow NATO forces to eventually come to the land of Crimea and Sevastopol, the land of Russian military glory, and cardinally change the balance of forces in the Black Sea area. This would mean giving up practically everything that Russia had fought for since the times of Peter the Great, or maybe even earlier—historians should know.”

Putin used to argue the invasion was necessary to save Crimea’s poor Russians from Ukrainian fascists. Now, everything but the kitchen sink seems to matter. Can any serious European statesman really believe that NATO forces would have been stationed in Crimea before Ukraine became a member of NATO (an eventuality that is highly unlikely in the short term and possibly longer)? Even more worrisome is how Putin links his imperialism to imperial Russia’s and himself to Peter the Great. Is that a sign of historical manipulation or megalomania?

Vanden Heuvel and Cohen: “the West’s jettisoning in February of its own agreement with then-President Viktor Yanukovych brought to power in Kiev an unelected regime so anti-Russian and so uncritically embraced by Washington that the Kremlin felt an urgent need to annex predominantly Russian Crimea, the home of its most cherished naval base.”

Putin invokes a phantom NATO threat, radical militants, and Russian imperialism. The Nation’s daring duo reduce Putin’s annexation to some bizarre (and physiologically painful!) “urgent need” and an irrational love for, of all things, a naval base!

Migranyan, meanwhile, has nothing coherent to say about Crimea. Except that even his incoherence rests on a contradiction. Thus, he insists that “Washington did not take into account the fact that Moscow had had no plans to take over Crimea or split Ukraine.” But then his language belies that claim: such phrases as “after Crimea’s return to Russia” and “the reabsorption of Crimea” (my emphasis) clearly suggest that he views Crimea as a natural part of Russia, which was merely “reabsorbing” what had always belonged to it.

Do these absurdities and contradictions matter? Personally, I’d like to think that coherence goeth before the fall.

OG Image: Europe and Central AsiaRussiaVladimir Putin

Europe and Central AsiaRussiaVladimir Putin

July 3, 2014

Ukrainians Die, as Europe Coos

Excuse the lurid title, but it’s only a variant of a headline that appeared many years ago in a New York tabloid: “Mother Dies, as Baby Coos.” I can’t speak for the accuracy of that headline, but today’s variant is, alas, all too valid. Because the fact is that Ukrainian soldiers are dying at the hands of Vladimir Putin’s terrorist hirelings as European states—and the European Union—are engaging the Kremlin with baby talk and diplo-babble.

Twenty-seven Ukrainian soldiers were killed by the terrorists during the cease-fire declared by President Petro Poroshenko more than a week ago (and which he ended on June 30th). Putin and his foreign minister, Sergey Lavrov, liked the cease-fire and wanted it to continue. What’s not to like from the Kremlin’s twisted point of view? As the terrorists continued to shoot at Ukrainians, Ukrainian soldiers continued to be sacrificed at the altar of diplo-babble.

Putin’s acquiescence in killing Ukrainians makes sense. After all, he’s demonized them as fascist vermin, and fascist vermin must, as every good Russian knows, be exterminated. European complicity in the killings makes rather less sense. After all, Europe is supposed to be a community of values. Europe is supposed to be committed to the promotion of democracy and human rights. Europe is supposed to be opposed to wars and fighting and killing.

Do European values stop at Ukraine’s borders? Evidently. But then why don’t they stop at Russia’s? Surely the Germans must see that Russia is not exactly a thriving democracy. Surely the French must see that Russia has engaged in an aggression against Ukraine. Or are they really so self-absorbed or dependent on the Kremlin mob that they are blinded to the atrocities taking place in Europe’s back yard?

If so, it’s small wonder that the European Union is experiencing a crisis. Its financial problems can be fixed. The EU’s real crisis is the mismatch between their words, their values, and their actions. If the EU really is a community of values, then it should act like one. If it’s too pusillanimous to defend the values it claims are at its core, then it should abandon all pretense of defending democracy and human rights and reinvent itself as a values-free zone.

If you think Ukrainian lives aren’t worth a café au lait in Paris or a stein of beer in Munich, then please say so. Have the courage to tell the Ukrainians: “You are not worth my comfort. Your lives are not worth the price of a steak frites. Your existence is of less importance to me than the existence of a juicy Schnitzel on my plate.”

So, France, deliver the two Mistral amphibious assault ships to Russia as the Kremlin continues its assault on Ukraine. A few more Ukrainians will die, but the espressos will flow in Paris.

And, Germany, by all means remain committed to sweet-talking Putin, even though you of all countries should know the difference between perpetrators and victims, aggression and resistance, dictatorship and democracy. A few more Ukrainians will die, but the beer will flow in Berlin’s Kneipen.

And, Austria, even though you should remember just what an Anschluss is, keep signing those pipeline deals. A few more Ukrainians will die, but the wine will continue flowing in Vienna’s wine gardens.

What’s not to like?

OG Image: Europe and Central AsiaUkraineRussiaVladimir PutinSergey Lavrov

Europe and Central AsiaUkraineRussiaVladimir PutinSergey Lavrov

June 25, 2014

Bawdy Lyrics Mock Putin in Ukraine

Ukrainians have taken to fighting back against Russia’s fascistoid dictator, Vladimir Putin, with obscenities and humor. A Ukrainian psychiatrist I recently saw on Ukrainian TV calls such behavior psychologically healthy during periods of “extreme stress”—an understatement for the savage war Putin and his terrorists have unleashed against Ukraine. The American social scientist James C. Scott might call both obscenity and humor “weapons of the weak.” Whatever you call them, they’re spreading like wildfire across Ukraine.

The case in point is a song or, more exactly, a chant that goes like this:

Putin khuylo

La-la la-la la-la la-la

“Khuylo” is the extremely vulgar Ukrainian term for penis. Its equivalents in English are well known (and, for the sake of my more sensitive readers, will go unmentioned). The words have been translated as “Putin is a d—khead” or as “Putin is a d—k,” but I prefer “Putin is a pr—k.” “D—khead” and “d—k” connote stupidity; “pr—k” connotes nastiness. And, I suspect, most Ukrainians view Putin as a nasty piece of work.

Soccer fans apparently first sang the chant on March 30, 2014, in Kharkiv, during a match between Kharkiv Metalist and Donetsk Shakhtar. Since then, the chant—whose lyrics and melody are readily accessible to all of Putin’s detractors, regardless of their musical abilities—has gone viral. If anything is a barometer of Ukrainian attitudes toward the man and his war-mongering, this, obviously, is it. A shorthand, more modest version of the lyrics has even entered the popular discourse. If you want to express your views of Putin, all you need do is say, “la-la la-la la-la,” and everything’s quite clear. One Ukrainian wit has even incorporated the two-word text into the Russian national anthem, a move that transposes his feelings about Putin to—gasp—Mother Russia (the implicit gender bending should appeal to postmodernists).

The democratic national deputy, Oleh Lyashko, who ran for president on May 25th and received over 8 percent of the vote, actually sang the song at a mass rally in Ternopil. That incident didn’t seem to annoy the Kremlin. But when Ukraine’s acting minister of foreign affairs, Andrii Deshchytsia, stated at a June 15th anti-Russian rally in Kyiv that he agreed that “Putin is a khuylo”—contrary to media reports, Deshchytsia never sang the chant—Moscow exploded, with calls for Deshchytsia’s resignation coming from his Russian counterpart, Sergei Lavrov, and the head of the Duma’s Committee on International Relations, Aleksei Pushkov.

The target of Ukrainian invective remained silent, but one can imagine that Putin—whom Hillary Clinton has called “thin-skinned”—must have been boiling mad.

Russia’s strongman obviously knows how to dish it out—remember that this is the man who called on chasing down Chechen terrorists “even in the outhouse”—but just as obviously can’t take it, especially when his hyper-masculine image is questioned.

Here’s Celestine Bohlen of the New York Times:

Asked by two French journalists on June 4 about [Hillary Clinton’s] comparison of Russia’s seizure of Crimea to Hitler’s aggression in the 1930s, Mr. Putin scoffed. “It’s better not to argue with women,” he said. “When people push boundaries too far, it’s not because they are strong but because they are weak. But maybe weakness is not the worst quality for a woman.”

Leaving aside the blatant sexism, Mr. Putin strayed into what for him is potentially dangerous territory. If pushing boundaries too far is a sign of weakness, then what to say about Mr. Putin’s own policies in Ukraine? When Russia annexes Crimea, when it gives tacit support to attacks by pro-Russian separatists on Ukrainian border posts, isn’t that—literally—about testing the frontiers of a neighboring sovereign state? Does that make it muscle-flexing by a weak man? …

Mr. Putin’s behavior with other leaders is often seen as a clue to the quality of his personal relationships with them. In theory, he and Chancellor Angela Merkel of Germany should have an excellent rapport; each speaks the other’s language, and the two countries have strong economic ties. And yet twice (most recently in the thick of the Ukrainian crisis), well aware of Ms. Merkel’s deep-seated fear of dogs, he let his big, black Labrador Koni into the room with her, even sniff her legs, and watched with a peculiarly passive expression.

On the occasions when he and Mr. Obama have sat together for photographers, the chill has been almost visible. Mr. Obama denies that he has a bad relationship with the Russian president, but it is clearly not a good one. For one thing, relations between the United States and Russia are strained. For another, Mr. Obama is a good six inches taller than Mr. Putin, an advantage probably not lost on someone who seems to put such stock in projecting an image of power.

This is odd behavior for a wannabe world statesman. Walking around bare-chested while holding big guns is embarrassing enough (although I don’t doubt that it goes well with the pre-Freudian ladies in Omsk), but purposely insulting strong women—whose strength, evidently, challenges his masculinity—takes the cake. Russia’s premier literary critic, Tatyana Tolstaya, recently referred to “little men with Napoleonic complexes” on Russian TV. Quite.

Putin’s “blatant sexism” may go some way to explaining his hatred of an independent Ukraine. In much Soviet propaganda, which Putin knows all too well, Ukraine was often represented as a peasant woman, while Russia was represented by a working-class man. In Putin’s world, Ukraine, like women, should stay quiet. And if they don’t? Obviously, you’re perfectly entitled to smack them around.

OG Image: Europe and Central AsiaRussiaUkraineUSVladimir Putin

Europe and Central AsiaRussiaUkraineUSVladimir Putin

June 19, 2014

How Putin Lost Ukraine

Half a year ago, in the fall of 2013, Ukraine was well on the way to becoming an authoritarian vassal state of Russia. Now, thanks to Russia’s neo-fascist dictator, Vladimir Putin, Ukraine is well on the way to becoming a democracy and a full-fledged member of the international community.

How did Putin snatch a humiliating defeat from the jaws of surefire victory? How could he have walked into a strategic trap of his own making? In a word, how did he lose Ukraine?

And make no mistake about it: it was Putin, and no one else, who lost Ukraine. He had it. He could easily have kept it. But now he’ll never have it again. And he has no one to blame but himself.

Putin has never understood Ukraine. For him, as for all too many Russians, it’s a historical mistake: a part of Russia that’s been swayed from the path of righteousness by a few dastardly fascist imperialist cigar-chomping bourgeois nationalists in cahoots with the CIA. If you treat a bona fide country with a bona fide people with a bona fide identity as your dirty backyard, don’t be surprised if you slip in the mud and fall on your face.

Putin’s first major slip was during the 2004 Orange Revolution, when, stupidly, he backed Viktor Yanukovych. That disaster taught Putin nothing, and, nine years later, he made the same mistake during the Euro Revolution. How could a supposedly smart leader back the same loser—not once, but twice? How could that same supposedly smart leader still insist that the loser remains Ukraine’s legitimate president—even after a fair and free election gave a huge mandate to Petro Poroshenko? The sad thing is that, after 15 years in power, Putin still doesn’t “get” Ukraine.

Putin’s most egregious blunder was to coerce Yanukovych into rejecting the Association Agreement with the European Union last fall. That strategic error led to the demonstrations in Kyiv, Yanukovych’s downfall, the emergence of a pro-Western, democratic Ukraine, and Russia’s transformation into a rogue state and sponsor of terrorism. That’s bad enough. Worse, Putin’s move was premised on his belief that the agreement would remove Ukraine from Russia’s sphere of influence. Sure, it would have provided Ukraine with a foothold in Europe, and, yes, it would have diminished Ukraine’s international isolation in the long run, but a Yanukovych-misruled Ukraine would have remained firmly ensconced in Russia’s backyard for a long time to come.

After all, with the Association Agreement as his main claim to fame, Yanukovych would have probably been reelected in 2015; the penetration of Kyiv’s government by agents of the Kremlin would have remained high or gotten higher; and the presence of Russian propaganda, business, and other forms of “soft power” would have only grown. Meanwhile, Ukraine’s military would have continued to decay, Ukraine’s foreign policy would have remained unremittingly pro-Russian, and a large segment of the Ukrainian population would have stayed ambivalent about Ukraine’s independence. The Europeans, meanwhile, and Germany in particular, would have remained indifferent to Ukraine. What’s not to like from the Kremlin’s point of view? A smart Russian president would have encouraged Yanukovych to sign the agreement with Brussels.

Alas, when it comes to Ukraine, Putin’s IQ takes a nosedive. Having sparked the Euro Revolution, having destroyed his pal Yanukovych, having embarked on the idiotic Crimean adventure, and having supported terrorism in the Donbas, Putin has forced Ukraine to become independent, democratic, and pro-Western. He’s forced it to develop an army and security apparatus. He’s forced the population to take sides and discover its Ukrainian identity—and pride. He’s forced the government to streamline the state apparatus. He’s forced elites to embrace democracy. And he’s forcing them to embark on radical economic reform and administrative decentralization. Faced with Putin’s aggression, Ukraine has no choice but to embody all the qualities—democracy, rule of law, tolerance, a functioning market economy—that Putin systematically destroys.

Worse still for Putin, his imperialism is driving Ukrainian elites to seek refuge in Western security institutions. Half a year ago, the elite and popular consensus in Ukraine was distinctly anti-NATO. The West, meanwhile, was suffering from “Ukraine fatigue” and had little interest in Ukraine as a strategic partner. Now, everything’s changed. Ukraine is the darling of the West, and Ukrainian public opinion on NATO is shifting.

Amazingly, Putin appears to think that, by supporting terrorism in eastern Ukraine, he can compel Ukraine to back away from the West. The effect, as any schoolboy confronted by a bully could have told him, is just the opposite. Faced with a hostile Russia, Ukraine has no choice but to turn westward. And, thanks to Putin’s treachery and mendacity, a democratic Ukraine will never again be the close, and fawning, partner of Russia that it was until a few months ago. Since Putin cannot be trusted, whatever deal Kyiv eventually signs with Moscow will at best establish a condition of formally peaceful relations between hostile neighbors (“cold peace”) or informally belligerent relations between hostile neighbors (“cold war”). Warily peaceful relations following a “de-annexation” of Crimea and recognition of Kyiv (“hot peace”) will be impossible as long as Putin remains in power.

For the time being, most Russians are still too bedazzled by Putin’s Tarzan yells to realize that he’s lost Ukraine irrevocably—and may be in the process of losing Russia. When they wake up to the reality of his “harebrained” blunders, Putin will discover that his sky-high ratings are as ephemeral as his swings on the vine are a pathetic pose.

Photo Credit. www.premier.gov.ru

OG Image: Europe and Central AsiaRussiaUkraineUSVladimir Putin

Europe and Central AsiaRussiaUkraineUSVladimir Putin

June 11, 2014

The End of the Donbas?

As Ukrainian army units battle it out with Putin’s terrorist commandos in eastern Ukraine, we should remember that, regardless of the outcome, the Donbas is probably dead. That may be good news for some and bad news for others, but the bottom line is that this uniquely regressive Ukrainian-Russian rustbelt region will never be the same.

Putin’s terrorists—both homegrown and imported from Russia—will almost certainly be defeated by forces loyal to Kyiv. Terrorists and separatists usually lose, especially under steppe-like conditions in which guerrillas do not thrive, and there’s no reason to think that Putin’s commandos will have any different fate from that of their counterparts in other countries. The only question is: how long will it take for their defeat to be final? For the longer it takes, the more unalterably different—and ruined—will the Donbas become.

As one resident of Donetsk recently wrote in a blog post:

No one believes that the people who live here are needed by anybody. We’ve been cast off, and Donetsk has become a cage, a prison, from which one can still escape if one abandons everything—apartment, property, work, hopes and plans for the future—so as to survive, which is the most important thing. Everyone understands that this will go on for a long time. That things will get very, very bad. That many will die. Just as the city will die.

Such words as terror, violence, and instability barely convey the reality of what living in a protracted war zone must be like for the residents of the Donbas. As violence becomes part of the fabric of everyday reality, physical survival becomes the average citizen’s primary, and perhaps only, concern. Compounding that concern is a collapsing economy. As stores close, plants and factories shut their gates, goods become scarce, and prices skyrocket, the black market booms, unemployment goes through the roof, wages aren’t paid, and crime takes off. People who long for normality will run: ethnic Ukrainians will probably head for Ukraine; ethnic Russians will head for Russia. The young, the talented, and the rich will be the first to go. The old, the weary, and the poor will be the last.

In the words of the Donetsk blogger:

Almost no one wants to leave, but everyone understands that flight will be necessary, because the city is doomed. No one believes in a happy or quick end. Neither do I…. Those who could flee have already left. Some people have evacuated their families from Donetsk. Many are getting ready to leave. Those who stay will be people who simply cannot leave. Or who still believe that things won’t be as bad as they are now.

Already, some 10,000 to 15,000 residents of Donetsk (population 982,000) appear to have fled; in Slovyansk (population 130,000), the site of widespread terrorist predations and heavy fighting, the number may be as high as 50,000. After the water supply was disrupted in early June in five cities—Druzhkivka, Dzerzhinsk, Kostyantynivka, Kramatorsk, and Slovyansk—the flow of refugees from them is sure to increase.

As infrastructure decays and people flee, institutions cease to function. Universities, research centers, the media, and other forms of intellectual activity will dry up as a result of the brain drain. Existing political and business elites will also disappear. The Party of Regions and the Communists—two political forces that have defined the Donbas and been defined by it—will become irrelevant as society unravels. Rinat Akhmetov, Ukraine’s richest man, could easily lose his shirt—and his clout.

The longer the fighting takes, the more likely will Donetsk and Luhansk provinces come to resemble a Hobbesian state of nature. As Thomas Hobbes put it:

In such condition, there is no place for industry; because the fruit thereof is uncertain: and consequently no culture of the earth; no navigation, nor use of the commodities that may be imported by sea; no commodious building; no instruments of moving, and removing, such things as require much force; no knowledge of the face of the earth; no account of time; no arts; no letters; no society; and which is worst of all, continual fear, and danger of violent death; and the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.

When the dust finally settles, democratic Ukraine will have to deal with a de-industrialized, depopulated, and de-modernized region. Under such conditions, all talk of federalism, decentralization, and language rights will sound quaint to people who want only to live.

How many refugees will return? Probably not too many. And how many of the survivors will be capable of engaging in entrepreneurship, innovation, and self-rule? Perhaps even fewer. How many lives will have been destroyed by Putin’s terrorist schemes? How many livelihoods? You can be sure that neither he nor his Western fans care or are counting.

Amid this possible doom and gloom, there may be a sliver of a silver lining. Putin’s criminality will have also destroyed the Soviet-era institutions, the Soviet-era mentality and political culture, and the Soviet-era economy that have conspired for decades to retard the Donbas’s integration into the modern world. Ironically, by destroying the Donbas, Russia’s neo-fascist dictator may pave the way for the Donbas’s eventual revival as an integral part of a thriving Ukrainian democratic state. The Donbas could stop being a problem for Kyiv precisely because, thanks to Putin, it could stop being.

OG Image: Europe and Central AsiaUkraine

Europe and Central AsiaUkraine

June 2, 2014

Enough False Rhetoric From Putin

I have one request to Russia’s fascistoid leader: stop lecturing Ukraine and the world.

I’ve been listening to you for close to 15 years now and, frankly, I’m tired of your half-baked views and cockamamie opinions. I know you think you know a lot about the ways of the world, Volodya, but permit me to let you in on a secret that everyone besides you knows: You don’t.

Just what makes you think that a career in the KGB qualifies you to speak authoritatively about anything—and, especially, about constitutions, democracy, and legitimacy? Indeed, former members of criminal organizations might be better advised to keep mum about the very things they spent their entire careers trying to destroy.

But it gets worse. After all, we know you plagiarized your dissertation:

According to official sources, Russian President Vladimir Putin holds a degree of candidate of economic science (incorrectly described on the English-language version of his website as a “Ph.D in economics”), awarded by the St. Petersburg Mining Institute in 1996. Putin never actually attended the institute, however, and the topic of the dissertation he submitted and defended was one in which he had no previous background. With the aim of exploring the mystery, Brookings [Institution] researchers Clifford Gaddy and Igor Danchenko in 2005 obtained a copy of the previously inaccessible dissertation and examined its contents. On March 30, 2006, … they also presented evidence of extensive plagiarism in the dissertation.

We also know that yours is a particular brand of ruthlessness. There is very strong evidence to suggest that you were in on the plot to bomb two apartment buildings in Moscow in September 1999, in which 300 Russian citizens were killed and several hundred others were wounded. As Amy Knight, a specialist on the KGB argues:

The evidence provided in [John Dunlop’s] The Moscow Bombings makes it abundantly clear that the FSB of the Russian Republic, headed by Patrushev, was responsible for carrying out the attacks. … Yet it is hard to imagine that they would have gone so far as to order bombings that they knew would kill so many innocent people. The more likely possibility is that the FSB was told by Yeltsin’s inner circle that violent acts were needed to destabilize Russia but that no specific instructions were given to blow up apartment buildings. The FSB, including its top leadership, responded by seizing the initiative. What, then, was the role of Putin, who was prime minister at the time, and also secretary of the Security Council? … as Dunlop demonstrates, … it is inconceivable that [this terrible act] would have been done without the sanction of Putin.

In October 2002, you crushed a Chechen seizure of the Dubrovka Theater in Moscow by killing 40 Chechens and 130 Russian hostages. Then, in September 2004, you crushed a Chechen takeover of a school in Beslan by killing a few dozen militants and 334 Russian citizens, including 156 children. And with a record like that, you have the temerity to accuse Kyiv of failing to negotiate with the terrorists you’ve sponsored and sent into eastern Ukraine. And you have the unmitigated gall to accuse Ukraine of being indifferent to civilian casualties!

You claim to have built up Russia’s economy, Volodya, but everyone knows you had nothing to do with sparking rapid GDP growth. All the credit goes to a huge spike in the price of oil and gas that, happily for you, coincided with your coming to power. Now that energy prices have leveled off and the shale gas revolution has taken place, let’s see you get the declining Russian GDP going again. I’m betting you’ll fail. Not that you won’t keep taking a big piece of the shrinking Russian economic pie. Just how much have you squirreled away in Western banks, Volodya? Is it $45 billion or $75 billion?

But, heck, if you want to destroy Russia and bamboozle the Russians, who am I to stop you? What really gets me is your moralizing Ukraine and the rest of the world about constitutions, democracy, legitimacy, and stability. You know, as well as everybody, that you’ve systematically violated Russia’s Constitution since 1999. You also know that you’ve dismantled every single democratic institution in Russia. You know that your legitimacy rests exclusively on your ability to pay off your cronies with your ill-gotten loot and buy off the population with promises of imperial grandeur and quick infusions of easy money. And you know that the major reason for instability in much of the post-Soviet world is your interminable meddling, and not the internal difficulties of the countries concerned. Stop infiltrating terrorists into Ukraine, Volodya, and I bet eastern Ukraine will quickly settle down.

Some people are impressed by your statecraft, but I’m not. You happen to have been at the right time in the right place. Just as Russia remains an Ivory Coast with a bomb, so, too, you remain a Yanukovych with gas. If it weren’t for all that filthy lucre that’s rained down on you, you would have long since been voted out of office by Russians. If it weren’t for your genuine skill at talking tough, democratic policymakers would have long since realized that your bare-chested bluster is just a cover for your policy incompetence.

So, Volodya, stop lecturing Ukraine about constitutions, democracy, legitimacy, and stability. Indeed, stop lecturing us about anything. Except, perhaps, on the mechanics of mendacity, death, destruction, and destabilization. Do everyone a favor, Volodya: please shut up.

Photo credit: www.kremlin.ru

OG Image: Europe and Central AsiaRussiaUkraineVladimir Putin

Europe and Central AsiaRussiaUkraineVladimir Putin

May 28, 2014

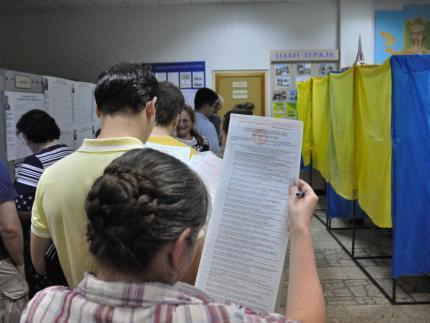

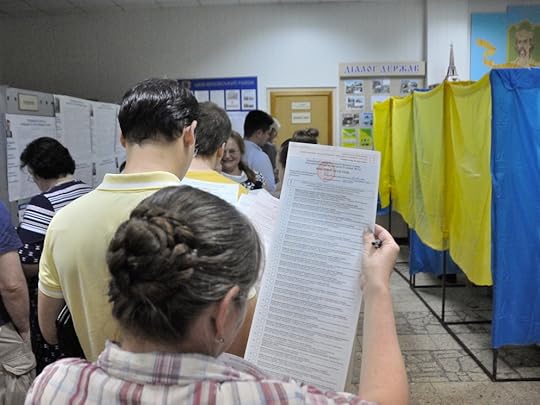

Ukraine’s Election Exposes Putin's Lies

Despite the best efforts of Vladimir Putin and his terrorist commandos in the eastern Donbas region, Ukraine’s presidential elections did in fact take place on May 25th, under conditions that international observers concur were fair and free. As of this writing, Petro Poroshenko appears to have won in one round.

Herewith a few lessons:

First, Ukraine is hardly the unstable almost-failed state that Putin and his Western apologists say it is. The terrorist violence was confined to two provinces—Luhansk and Donetsk. In the rest of the country, the voting proceeded smoothly. On top of that, Ukraine’s security forces were able to maintain law and order in much of the country, a positive development that builds on the armed forces’ creditable performance in their “anti-terrorist operations” in April and May.

Second, Ukraine is anything but the illegitimate state Putin and his western apologists say it is. Voting participation for the entire country was high: about 60 percent. Not including the two provinces that were terrorized by Putin’s commandos, participation was even higher. Everyone knows that the only thing that kept Ukrainians in the Donbas from voting was Putin’s terrorists.

Third, Putin’s terrorist commandos have been outflanked by the elections. People want stability; they want a return to normality. And they know that elections can bring about both. The terrorists, like Putin, have nothing but violence to offer. That is not a winning electoral platform. Nor is it any way to win the hearts and minds of the eastern Ukrainian population the terrorists claim to be defending from wild-eyed Ukrainian “fascists.” Small wonder that, after hemming and hawing for several months, even Ukraine’s richest oligarch, Rinat Akhmetov, got off the fence and denounced the terrorists, while calling on Donbas residents to take to the streets and march in protest. (And, in an indication of just what is still so wrong with the Donbas, hundreds of thousands heeded his call. Were they not, one might well ask, capable of acting on their own—without being told to do so by some higher-up?)

Fourth, while Ukraine now has a legitimately elected president, Putin has egg on his face—lots of it. Russia’s fascistoid dictator can continue questioning democratic Ukraine’s legitimacy, and he is perfectly entitled to believe that fair and free elections are unfair and un-free, but at some point such truculence becomes nothing more than childishness, stupidity, and petulance. Come to think of it, haven’t those three qualities defined Putin’s behavior since the fall of 2013, when he coerced Ukraine’s since-deposed sultan, Viktor Yanukovych, into backing out of the Association Agreement with the European Union? Ask yourself this: just what has Putin gotten out of this entire crisis? An arid peninsula with enormous economic and political problems, a spike in his popularity, and affirmations of love from his Western apologists. And just what has he lost? Good relations with the West, good relations with Ukraine, and the prospect of a rapid recovery of Russia’s moribund economy. Isn’t it time to recognize the obvious: that Putin’s statecraft is about as refined as Yanukovych’s?

Fifth, Ukraine’s much touted, much decried, and much denounced “radical, right-wing extremists” attracted about 1–2 percent of the vote—which surprised no one who knows a bit about Ukrainian politics. (Contrast that with the 25 percent achieved by France’s National Front in the May 25th elections to the European Parliament.) In a word, Ukraine’s right-wingers are a fringe phenomenon that has played no serious role in Ukraine’s national politics, is playing no serious role in Ukraine’s national politics, and will continue to play no serious role in Ukraine’s national politics. All those Western, Russian, and Ukrainian analysts who’ve been beating the drum about the nefarious influence of Ukraine’s right in the last few years—while turning a blind eye to the extremism of Yanukovych’s thuggish regime and the even worse extremism of the pro-Russian hyper-chauvinists who eventually became the core of Putin’s terrorist commandos in eastern Ukraine—have some serious crow to eat. And some serious apologies to make: for diverting attention from the real danger in Ukraine to their own personal obsessions.

Sixth, it may be time to be guardedly optimistic about democratic Ukraine’s prospects. True, the Donbas will remain a problem for a long time, but Putin’s terrorists are unlikely to branch out to other parts of the country. As Turkey, Israel, Colombia, and many other countries have shown, life can go on, even when terrorists are ensconced in regional strongholds. More important, Putin and his terrorists appear to be in a dead end. The government of Prime Minister Arseniy Yatsenyuk has a serious reform program that should bring about radical economic change and a whole-scale decentralization of authority. The newly elected president has good credentials and a huge popular mandate. The West—the United States, the European Union, the International Monetary Fund, and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization—supports Ukraine and will make sure that reforms are in fact implemented. Finally, the capital city, Kyiv, has a new mayor, the pro-Western reformer, Vitaly Klitschko.

Not bad for a country that, according to Putin’s Russian propagandists and Western apologists, is supposedly on the verge of collapse.

OG Image:

Europe and Central AsiaUkraineRussiaVladimir PutinElection

Europe and Central AsiaUkraineRussiaVladimir PutinElection

May 23, 2014

Why Germans Are Smitten With Putin

The German liberal newspaper Die Zeit recently shed a bright light on the German population’s odd love affair with Russian President Vladimir Putin. Germans profess a love of democracy and human rights; Putin has done everything in his power to destroy democracy and human rights. Germans stand for peace; Putin has unleashed war on Ukraine in 2014 (and on Georgia in 2008).

“Why do so many German citizens judge the crisis in Crimea in a completely different way than politicians and the media?” asks Bernd Ulrich. “Unless surveys are misleading, two-thirds of German citizens, voters, and readers stand opposed to four-fifths of the political class.” The former either approve of or are indifferent to Putin’s aggression in Ukraine. The latter are aghast. (With some significant exceptions: e.g., former socialist chancellors Helmut Schmidt and Gerhard Schröder. Schmidt defended Putin’s Anschluss of Crimea, while Schröder recently invited Russia’s version of the “good Hitler” to his 70th birthday bash.)

Ulrich identifies five reasons for this divide.

The first is the perceived arrogance of the West (read Washington) since 9/11. “Many are now saying that limits need to be placed on” Washington’s highhandedness, and if German Chancellor Angela Merkel “can’t do it, then maybe Vladimir Putin can.”

The second is the perceived arrogance of the “Euro machine”: “Putin claims that the EU backed him into a corner with its association agreement for Ukraine. One could bet that the vast majority of people within the EU were just as surprised by the fact that yet another country was supposed to be associated to it…. the majority seems to feel this ominous mix of foreign presumptuousness and personal powerlessness not only toward Washington, but also toward Brussels.”

The third is the perceived arrogance of the media: “When the vast majority of media make arguments along the same lines, as is the case with Ukraine, it is anything but easy—even for well-intentioned readers—to discern whether what we are dealing with here (a) is once again an instance of hype, (b) is a tacit measure to educate the populace, or (c) is a case of deep-seated convictions concerning democracy and human rights.”

The fourth is the suspicion that the West is unwilling and unable to engage in military solutions:

The entire discussion about Russia and Putin is being poisoned by the presumption that, to some people, this is about much more than Crimea and Ukraine…. We are less and less willing to intervene, and arms expenditures are declining, even in the US now. In Germany, this development is proceeding in a particularly rapid and radical fashion. People haven’t properly come to terms with the disappointment of Afghanistan, and Germans said “no” to both war in Iraq and intervention in Libya. The respective reasons for staying on the sidelines were of a kind that makes it difficult to even imagine any major military intervention in which Germans would participate.

The first three reasons are situational (they depend on post-9/11 developments) and, thus, could change. The fourth may reflect an attitudinal disposition that appears to be taking root today. It, too, could change (and if it doesn’t, Germany’s eastern European NATO partners had better watch out).

Ulrich’s fifth reason is rooted in German political culture:

For us, the postwar period was characterized by wrestling with suppressing or accepting the Holocaust, by the German guilt for having murdered 6 million Jews. But other types of guilt have lingered behind that, including that for killing millions of Russians…. This is one of the main reasons why there now appears to be significant willingness here in Germany to concede a “zone of influence” to the Russians. The thinking here is: Haven’t they already been hurt and penalized enough by the loss of their Soviet empire? Should we Germans, of all people, argue with them over Ukraine?

This view, of German guilt for Russian deaths, is extremely widespread. German intellectuals, policymakers, and average citizens speak of World War II as the “Vernichtungskrieg gegen Russland” (the war of destruction against Russia); accordingly, the millions of civilian and military casualties were suffered by “die Russen.” The terminology goes back to the war, when the Nazi regime characterized its enemy in exactly the same terms.

The reality was quite different. Nazi Germany devastated, above all, Poland, Belarus, and Ukraine—and not Russia. This is not a question of who suffered most, but, quite simply, of setting the historical record straight. Which Ulrich, to his credit, does:

Today, with a view to German guilt, the right to self-determination of another people—Ukrainians—is once again being disputed. Should they not be allowed into the EU because Germans justifiably have a guilty conscience vis-à-vis Russians? The fact that Germans and Russians are once again making decisions about the fate of Ukraine would be a perverse lesson to learn from history for this country, which suffered under both nations like no other. The Soviet Union and Nazi Germany killed millions upon millions of people on Ukrainian territory with planned famines, pogroms, and extermination campaigns. During the years when Stalin and Hitler were in power, more people died here than anywhere else in Eastern Europe. Likewise, millions of the “Russians” that German soldiers killed during World War II were actually Ukrainian citizens of the Soviet Union. The current debate ignores the havoc that Nazi and Soviet imperialism wreaked in this country. In today’s crisis, the price is being paid for the fact that Germans have not yet arrived in their collective memory at a place where they can view the fate of Ukrainians as Ukrainians.

That last sentence is key. Ukrainians, like Belarusians, do not exist in the German consciousness. During the war, they were Untermenschen (subhumans). At present, they are, for the majority of Germans, not even worth the disdain that the modifier unter conveys. How convenient for German defense contractor Rheinmetall, which has been happily training Russian troops. And how convenient for the German public: if Russia invades Ukraine and kills thousands of Ukrainians, Germans will be able to assuage their guilt by shedding a tear for poor Putin.

Photo Credit: RIA Novosti

OG Image: Europe and Central AsiaGermanyRussiaUkraineGeorgiaVladimir Putin

Europe and Central AsiaGermanyRussiaUkraineGeorgiaVladimir Putin

May 13, 2014

Separatists Terrorizing, Kidnapping, Beating Citizens in Ukraine

Several weeks ago, I had written of a woman, G, from the town of Druzhkivka, in Donetsk Province, who had noted in her last e-mail to me: “Alexander, they will kill us.” In turn, I had ended my blog post with the comforting words: “I haven’t heard from G since that last note. Although I’m sure she and her family are safe, I still shudder at the thought of how terrified she must have been to have expected death—for nothing more than her identity as a Ukrainian in the unremittingly hostile environment created by Putin’s deliberate attempt to create havoc in her country.”

I was wrong. G and her family are not safe. Their lives are in danger from pro-Russian terrorists precisely because they are Ukrainian patriots.

I just received two more e-mails from her, translated by me from the Ukrainian and reprinted below in full.

From Saturday, May 10th, 8:42 a.m.:

Dear Alexander: a terrible misfortune has befallen my family. Molotov cocktails were thrown at my parents’ house; my parents, my husband, and I were threatened; and then armed commandoes shot at my parents’ house. The press and the Internet wrote about this [link]. Here’s one report: Yevhen Shapovalov’s building was shot at from a jeep, then it was broken into and ransacked, and all the valuables were taken. The neighbors called the militia, but they didn’t even go inside; they took some photographs of the outside and said they’d lay a trap. A few days ago they threw three Molotov cocktails at Yevhen’s building; miraculously, it didn’t catch fire; there was a small child inside, about which everyone in the neighborhood knew. Today, the terrorists attacked an empty building, as the entire family had fled. Yevhen Shapovalov is the head of the Oleksa Tykhy Society of Donetsk Province (a branch of the Prosvita Society) [Tykhy was a prominent Ukrainian dissident; the Prosvita Society concerns itself with the promotion of Ukrainian language and culture]. For the terrorists, Yevhen, like all Ukrainian patriots, is the class enemy. PS. Yevhen is also a member of our civic organization. We are currently in hiding. H and my other daughter are with me. Horrible things are taking place around us…

From Sunday, May 11th, 6:53 a.m.:

Dear Alexander: I’ve changed my e-mail address because the thugs are after my husband and me. They seized three young girls in Kramatorsk today for organizing the delivery of food to Ukrainian soldiers stationed near Sloviansk. One of them is my colleague; we had been talking just a day ago. One of the girls was released with broken ribs and torn-out hair; she was ordered to come back tomorrow with money… What are we to do? These fascists are just like the NKVD, even worse. I’m constantly on edge, while my mother had a heart attack. What have peaceful people like us done to deserve this? We’re hiding in difficult circumstances, the children are ill, H isn’t going to school. That’s what our life looks like…. We pray, but we’re losing hope.

What’s next for G and her family? Serious physical harm, including death, at the hands of Putin’s gangsters is no longer out of the question. Call me irrational, but if G and her family lose their lives I will hold Russia’s fascist president and his Western apologists (from Gerhard Schröder to Helmut Schmidt to Henry Kissinger to Stephen F. Cohen) morally responsible. They may not have thrown the Molotov cocktails, but in justifying Putin’s aggression they share in his guilt for whatever atrocities Putin’s commandoes commit.

The political message of this persecution should be obvious. Putin’s terrorists are committed to cleansing the Donbas of Ukrainian patriots—which is to say, of Ukrainians—as in their twisted understanding of identity anyone who speaks Ukrainian is necessarily their enemy. Such an attitude deserves to be called what it is: supremacism, racism, and hate. These, then, are the fruits of Putin’s aggression.

As Europeans and Americans contemplate what to “do” about Putin, they should remember that he and his minions stand for everything the civilized world rejects. The United States and the European Union hope that Druzhkivka will be confined to eastern Ukraine. Unless they act more forcefully to stop Putin and his terror troops, the Putinite values on display in Druzhkivka may one day come to Europe.

OG Image: Europe and Central AsiaRussiaUkraineUSVladimir Putin

Europe and Central AsiaRussiaUkraineUSVladimir Putin

Alexander J. Motyl's Blog

- Alexander J. Motyl's profile

- 21 followers