Natan Slifkin's Blog, page 163

November 12, 2013

Manipulating with Mysticism for Money

You could fill an entire book with examples of tzedakah organizations manipulating people's emotions for money. One of the most appalling examples I've seen is from an organization seeking to raise funds for, you guessed it, Torah study. This one promised to learn in the merit for people to get a shidduch. The picture in the ad was not of people studying Torah - the cause that they are trying to promote. Instead, it was of a sparkling diamond engagement ring. The message effectively being broadcast was: "Attention all singles - think about how desperate you are to get married! Don't miss this opportunity! Give us money!"

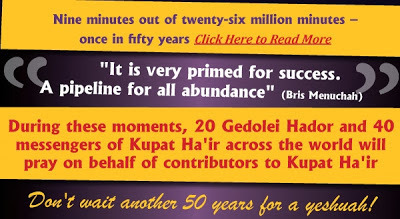

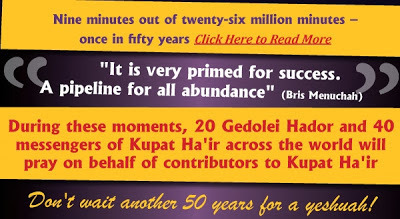

Mysticism provides these organizations with an especially potent tool for manipulating people, and today, the ninth of Kislev, demonstrates a powerful example. Kupat Ha'ir, the world's greatest Orthodox Jewish experts at manipulating people via mysticism, put out the following ad:

For those who can't see the picture, it says that there is a once-in-fifty years opportunity to take advantage of the ninth hour of the ninth day of the ninth month of the ninth year in the Yovel-cycle. This full house of nines, according to an obscure ancient sefer, is an auspicious hour for prayer. But why pray yourself, when other people can pray on your behalf? Twenty Gedolei HaDor (I never knew there were that many!) will pray for you - provided that you give money to Kupat Ha-Ir!

And then comes the most manipulative line of all: "Don't wait another 50 years for a yeshuah!" You are desperate for salvation from your problems, and you need to give us money in order to attain it, or you'll be stuck for fifty years! Forget about Rosh HaShanah and Yom Kippur - it's this once-in-fifty-years opportunity that counts. As the Kupat HaIr website states: "Doesn’t it make sense to overextend yourself for nine minutes for the sake of your entire life? ... Your life depends on these 9 minutes. Will you be happy? Will you have money? What will your health be like? How will you be spared unfavorable decrees?"

Yes, they are raising money for a good cause. (At least, to some extent; I don't know how much of their charity goes to perpetuating the kollel system.) But I'm sure that there are many people who truly can't afford to give, but who do so out of sheer terror that they might be losing their chance to get married, to have children, to be healthy. I personally know of someone who themselves fell into dire straits because of this. And Rav Mattisyahu Solomon of Lakewood has decried the fact that single women desperate for a yeshua had contributed all their savings to Kupat HaIr, and turned to him when they didn't get married. He described Kupat HaIr's modus operandi as "absolute theft."

Furthermore, this form of fundraising spreads the idea that charitable acts are done in order to attain personal salvation, rather than to actually help others. And the next person promising miracles will take your money not to give to charity, but for their own pockets.

There is also the problem of the wider context: in the ultra-Orthodox community, there is a prevalent message that it is wrong and futile to engage in regular efforts to obtain parnassah (i.e. education, training and work). There is a real risk of people focusing on segulos instead of doing the necessary hishtadlus.

And all this is quite aside from the falsehood in the campaign. No, your entire life does not depend on these nine minutes! Oh, and by the way: due to uncertainties about when yovel actually is, Kupat Ha-Ir ran the very same campaign four years ago, announcing that 1:43pm of November 26th 2009 was the ninth of the ninth of the ninth of the ninth! And they ran it again in 2011, claiming that that was the ninth of the ninth of the ninth of the ninth!

This sick, manipulative behavior all occurs, according to Kupat HaIr, with the backing of the (charedi) Gedolei HaDor. Fortunately, however, there are other rabbinic voices. Rav Shlomo Aviner delivered a lecture in his yeshivah in which he condemns the Four Nines as an attempt to use magic and shortcuts in place of genuine spiritual growth. As he points out, if it is so important, why is it not in the Torah? In the Gemara? In any of the major works of Judaism? Why didn't any of the famous rabbis of history mention it? And what's so special about the number nine, anyway? We need, says Rav Aviner, to focus on the truly important things, such as improving our characters. We should not be attempting to invent new magical shortcuts to salvation.

It's great to give charity. But give it to an organization that works in the right way, not one that tries to take advantage of people's fears. My personal favorite charity is Lemaan Achai, whose "gimmick" is not some mystical mumbo-jumbo, nor false promises of salvation, but rather that they practice charity in accordance with the highest ideals: working to wean people off charity. They don't raise as much money as Kupat Ha-Ir - but what they do raise, is raised honorably.

(Hat-tip to those who sent in the links. See too my post on The Ring Of Power)

Mysticism provides these organizations with an especially potent tool for manipulating people, and today, the ninth of Kislev, demonstrates a powerful example. Kupat Ha'ir, the world's greatest Orthodox Jewish experts at manipulating people via mysticism, put out the following ad:

For those who can't see the picture, it says that there is a once-in-fifty years opportunity to take advantage of the ninth hour of the ninth day of the ninth month of the ninth year in the Yovel-cycle. This full house of nines, according to an obscure ancient sefer, is an auspicious hour for prayer. But why pray yourself, when other people can pray on your behalf? Twenty Gedolei HaDor (I never knew there were that many!) will pray for you - provided that you give money to Kupat Ha-Ir!

And then comes the most manipulative line of all: "Don't wait another 50 years for a yeshuah!" You are desperate for salvation from your problems, and you need to give us money in order to attain it, or you'll be stuck for fifty years! Forget about Rosh HaShanah and Yom Kippur - it's this once-in-fifty-years opportunity that counts. As the Kupat HaIr website states: "Doesn’t it make sense to overextend yourself for nine minutes for the sake of your entire life? ... Your life depends on these 9 minutes. Will you be happy? Will you have money? What will your health be like? How will you be spared unfavorable decrees?"

Yes, they are raising money for a good cause. (At least, to some extent; I don't know how much of their charity goes to perpetuating the kollel system.) But I'm sure that there are many people who truly can't afford to give, but who do so out of sheer terror that they might be losing their chance to get married, to have children, to be healthy. I personally know of someone who themselves fell into dire straits because of this. And Rav Mattisyahu Solomon of Lakewood has decried the fact that single women desperate for a yeshua had contributed all their savings to Kupat HaIr, and turned to him when they didn't get married. He described Kupat HaIr's modus operandi as "absolute theft."

Furthermore, this form of fundraising spreads the idea that charitable acts are done in order to attain personal salvation, rather than to actually help others. And the next person promising miracles will take your money not to give to charity, but for their own pockets.

There is also the problem of the wider context: in the ultra-Orthodox community, there is a prevalent message that it is wrong and futile to engage in regular efforts to obtain parnassah (i.e. education, training and work). There is a real risk of people focusing on segulos instead of doing the necessary hishtadlus.

And all this is quite aside from the falsehood in the campaign. No, your entire life does not depend on these nine minutes! Oh, and by the way: due to uncertainties about when yovel actually is, Kupat Ha-Ir ran the very same campaign four years ago, announcing that 1:43pm of November 26th 2009 was the ninth of the ninth of the ninth of the ninth! And they ran it again in 2011, claiming that that was the ninth of the ninth of the ninth of the ninth!

This sick, manipulative behavior all occurs, according to Kupat HaIr, with the backing of the (charedi) Gedolei HaDor. Fortunately, however, there are other rabbinic voices. Rav Shlomo Aviner delivered a lecture in his yeshivah in which he condemns the Four Nines as an attempt to use magic and shortcuts in place of genuine spiritual growth. As he points out, if it is so important, why is it not in the Torah? In the Gemara? In any of the major works of Judaism? Why didn't any of the famous rabbis of history mention it? And what's so special about the number nine, anyway? We need, says Rav Aviner, to focus on the truly important things, such as improving our characters. We should not be attempting to invent new magical shortcuts to salvation.

It's great to give charity. But give it to an organization that works in the right way, not one that tries to take advantage of people's fears. My personal favorite charity is Lemaan Achai, whose "gimmick" is not some mystical mumbo-jumbo, nor false promises of salvation, but rather that they practice charity in accordance with the highest ideals: working to wean people off charity. They don't raise as much money as Kupat Ha-Ir - but what they do raise, is raised honorably.

(Hat-tip to those who sent in the links. See too my post on The Ring Of Power)

Published on November 12, 2013 01:47

November 11, 2013

Gedolim Wars, Episode IV: A New Hope

Over a year ago, in a post entitled Yated Wars: Reactions to the New Charedim, I described the emerging battle between two factions in the Israeli Litvishe Charedi world. One faction is of extreme charedim, who believe that one should not support hospitals, only yeshivos, and that one should not educate one's children towards earning a living. And that's the more moderate group! The other faction is even more zealous in its opposition towards any sort of accommodation with wider Israeli society. The first group is under the banner of Rav Aharon Leib Steinman and Rav Chaim Kanievsky, and runs the Yated newspaper; the second group rallies behind Rav Shmuel Auerbach, and runs the HaPeles newspaper.

For those who are unaware, in the last few weeks the hostility between the two factions has reached epic proportions. This was related to the municipal elections, in which the two groups fielded different political parties, Degel haTorah and Bnei Torah (a.k.a. Etz). It made the Bet Shemesh electoral unpleasantness look like child's play by comparison.

People in many kollels were instructed to sign a loyalty oath (!), stating that they will follow Rav Steinman and Rav Kanievsky, and will not read HaPeles, or else they will be expelled. The invective from Rav Shmuel Auerbach's side was equally incendiary, to the point that a somewhat deranged young man physically assaulted Rav Steinman. And in the latest episode, Rav Chaim Kanievsky described the people in Rav Shmuel Auerbach's camp as "animals," and said that Rav Shmuel is a zaken mamre who is chayyav skilah (liable for death by stoning)!

To say that all this is causing a crisis in rabbinic authority is putting it mildly. While Rav Aharon Feldman considered the ban on my books to have caused the greatest crisis in rabbinic authority in recent memory, this may well supersede it, at least for some people. After all, the Torah-science ban just pitted Gedolim against Rishonim; this fight pits Gedolim against Gedolim.

Just think about the questions that have been raised. Someone asked Rav Chaim Kanievsky if a lifetime disciple of Rav Shmuel Auerbach is allowed to follow his direction, and Rav Chaim answered in the negative. What on earth does this mean? I'm certainly no fan of Rav Shmuel's approach, but I don't understand the conceptual model of rabbinic authority in which his followers are told by others that they are forbidden to listen to him.

Over at Cross-Currents, Rabbi Adlerstein presented a lecture by Rav Rubin, which attempts to provide an explanation of why it is forbidden for people to follow Rav Shmuel Auerbach, but it raises more problems than it solves. Why is unthinkable for there to be two different groups? After all, we already have Sefardim and Ashkenazim, Litvaks and Chassidim, Charedim and Dati-Leumi. Why is it forbidden for Litvishe Charedim to further sub-divide?

One person argued to me that for strategic political reasons, it's important for the Litvishe Charedim to be united around one voice. Well, obviously Rav Shmuel Auerbach has a different idea about strategies! Why is his view automatically disqualified?

And who says that Rav Steinman takes precedence over Rav Shmuel Auerbach? Some might say that the idea being presented here is that there is a Gadol HaDor, a single greatest Torah authority that everyone is deemed to follow, and that person is Rav Steinman. But this lacks any basis in halachah or tradition. Furthermore, it would mean that if Rav Steinman and Rav Kanievsky passed away, which would (in the charedi Litvishe mindset) leave Rav Shmuel as the greatest Torah authority, then everyone would have to follow him!

Another claim is that Rav Shmuel Auerbach is a zaken mamre (rebellious elder), because he is going against the majority. But last I checked, it takes a Sanhedrin to have a zaken mamre. Did Rav Ovadiah Yosef have to follow the Ashkenazi Gedolim, if they were in the majority?

Rav Rubin also claims that the level of aggression coming from the Rav Shmuel Auerbach camp demonstrates their illegitimacy. But no less aggression has come from Rav Steinman's camp, especially in light of Rav Chaim Kanievsky's recent statements.

Is there any good that can come out of all this? I believe so.

Consider the ban on my books. Contrary to Rav Feldman, I don't think that the ban on the rationalist Torah-science approach was a disaster for rabbinic authority. It was only a disaster for novel Charedi concepts of rabbinic authority, relating to "Gedolim" and Daas Torah. People gave up on following the Gedolim, and instead turned to their local rabbanim. The traditional type of rabbinic authority - a person's own community rabbi, who is of a similar background and understands him - was strengthened.

A similar phenomenon could occur here. As the charedi world, to put it in the words of Rabbi Eidensohn, "self-destructs," many people may realize how seriously problematic it is, especially with regard to its notions of charedi superiority, rabbinic authority, and Gedolim. Hopefully, they will return to a more traditional and healthier form of Judaism.

For those who are unaware, in the last few weeks the hostility between the two factions has reached epic proportions. This was related to the municipal elections, in which the two groups fielded different political parties, Degel haTorah and Bnei Torah (a.k.a. Etz). It made the Bet Shemesh electoral unpleasantness look like child's play by comparison.

People in many kollels were instructed to sign a loyalty oath (!), stating that they will follow Rav Steinman and Rav Kanievsky, and will not read HaPeles, or else they will be expelled. The invective from Rav Shmuel Auerbach's side was equally incendiary, to the point that a somewhat deranged young man physically assaulted Rav Steinman. And in the latest episode, Rav Chaim Kanievsky described the people in Rav Shmuel Auerbach's camp as "animals," and said that Rav Shmuel is a zaken mamre who is chayyav skilah (liable for death by stoning)!

To say that all this is causing a crisis in rabbinic authority is putting it mildly. While Rav Aharon Feldman considered the ban on my books to have caused the greatest crisis in rabbinic authority in recent memory, this may well supersede it, at least for some people. After all, the Torah-science ban just pitted Gedolim against Rishonim; this fight pits Gedolim against Gedolim.

Just think about the questions that have been raised. Someone asked Rav Chaim Kanievsky if a lifetime disciple of Rav Shmuel Auerbach is allowed to follow his direction, and Rav Chaim answered in the negative. What on earth does this mean? I'm certainly no fan of Rav Shmuel's approach, but I don't understand the conceptual model of rabbinic authority in which his followers are told by others that they are forbidden to listen to him.

Over at Cross-Currents, Rabbi Adlerstein presented a lecture by Rav Rubin, which attempts to provide an explanation of why it is forbidden for people to follow Rav Shmuel Auerbach, but it raises more problems than it solves. Why is unthinkable for there to be two different groups? After all, we already have Sefardim and Ashkenazim, Litvaks and Chassidim, Charedim and Dati-Leumi. Why is it forbidden for Litvishe Charedim to further sub-divide?

One person argued to me that for strategic political reasons, it's important for the Litvishe Charedim to be united around one voice. Well, obviously Rav Shmuel Auerbach has a different idea about strategies! Why is his view automatically disqualified?

And who says that Rav Steinman takes precedence over Rav Shmuel Auerbach? Some might say that the idea being presented here is that there is a Gadol HaDor, a single greatest Torah authority that everyone is deemed to follow, and that person is Rav Steinman. But this lacks any basis in halachah or tradition. Furthermore, it would mean that if Rav Steinman and Rav Kanievsky passed away, which would (in the charedi Litvishe mindset) leave Rav Shmuel as the greatest Torah authority, then everyone would have to follow him!

Another claim is that Rav Shmuel Auerbach is a zaken mamre (rebellious elder), because he is going against the majority. But last I checked, it takes a Sanhedrin to have a zaken mamre. Did Rav Ovadiah Yosef have to follow the Ashkenazi Gedolim, if they were in the majority?

Rav Rubin also claims that the level of aggression coming from the Rav Shmuel Auerbach camp demonstrates their illegitimacy. But no less aggression has come from Rav Steinman's camp, especially in light of Rav Chaim Kanievsky's recent statements.

Is there any good that can come out of all this? I believe so.

Consider the ban on my books. Contrary to Rav Feldman, I don't think that the ban on the rationalist Torah-science approach was a disaster for rabbinic authority. It was only a disaster for novel Charedi concepts of rabbinic authority, relating to "Gedolim" and Daas Torah. People gave up on following the Gedolim, and instead turned to their local rabbanim. The traditional type of rabbinic authority - a person's own community rabbi, who is of a similar background and understands him - was strengthened.

A similar phenomenon could occur here. As the charedi world, to put it in the words of Rabbi Eidensohn, "self-destructs," many people may realize how seriously problematic it is, especially with regard to its notions of charedi superiority, rabbinic authority, and Gedolim. Hopefully, they will return to a more traditional and healthier form of Judaism.

Published on November 11, 2013 06:36

November 7, 2013

The Marvellous Mandrake and the Mashgiach of Mir

The mandrake is an odd plant that, in the ancient world, was thought to have all kinds of marvelous properties, from being a fertility aid to having magical powers. The mandrake, which appears in this week's parashah, also had a wondrous effect on me: it had a pivotal role in transforming me into a rationalist.

My formative yeshivah years were spent in a decidedly anti-rationalist environment. I was taught that the system of natural law is an unfortunate entity that exists solely in order to enable free will - we have to have the possibility of blinding ourselves to God's stewardship of the universe. To the extent that a person rises in their spiritual level, they will be above the natural order.

Then I came across a discussion in Daas Chochmah U'Mussar 1:14 by Rabbi Yerucham Levovitz (1874-1936), mashgiach of the Mirrer Yeshivah. He focuses upon the episode of Rachel and the mandrakes that appears in this week's parashah:

But, for an anti-rationalist yeshivah bochur, far from explaining matters, this only served to complicate them further. After all, this isn’t just an ordinary person that we are talking about, but Rachel, wife of Jacob, one of the matriarchs and a righteous person of the highest stature. Surely she was fully aware that it was God Who was withholding children from her rather than any physical problem! And it was surely just as clear that her salvation would be through prayer, not through fertility drugs!

But Rav Yerucham Levovitz explained the Seforno in a way that transformed my attitude. He explains that natural law is not to be seen as conflicting with God’s authority. Just the opposite — it is a manifestation of His wisdom. God doesn't just make things happen arbitrarily; there is a system of cause-and-effect. It is important to recognize, says Rav Yerucham, that this is also true of spirituality - one's deeds, words and even thoughts have an effect. If a person does not see the system of cause-and-effect in nature, he will not see it in his spiritual life. If there is no derech eretz, no acknowledgment of a system to the world, then there is no Torah.

It took a while for me to fully absorb this message. Initially, when I recorded it in my youthful and primitive book Second Focus, I still wrote that Rachel's usage of a fertility drugs was in no way a cause of her having children, just a merit. But Rav Yerucham had set me on the path to Maimonidean rationalism. I had begun to see that natural law is not a negative phenomenon that just exists to give us free will, but rather it is the proper way for God to run the world. And when I eventually applied that line of thinking to the development of the universe and of life, I realized that it would be appropriate for God to have done this via an orderly system of natural law, rather than zapping things into existence.

So, that's how I came to a rationalist view of nature - from a marvelous mandrake and a mashgiach of Mir!

My formative yeshivah years were spent in a decidedly anti-rationalist environment. I was taught that the system of natural law is an unfortunate entity that exists solely in order to enable free will - we have to have the possibility of blinding ourselves to God's stewardship of the universe. To the extent that a person rises in their spiritual level, they will be above the natural order.

Then I came across a discussion in Daas Chochmah U'Mussar 1:14 by Rabbi Yerucham Levovitz (1874-1936), mashgiach of the Mirrer Yeshivah. He focuses upon the episode of Rachel and the mandrakes that appears in this week's parashah:

In the days of the wheat-harvest, Reuben went and found mandrakes in the field. He brought them to Leah, his mother. Rachel said to Leah, “Please give me some of your son’s mandrakes!” (Genesis 30:14)Why was Rachel so eager for these flowers? The fifteenth-century Italian commentator Rabbi Ovadiah Seforno states that "these are a type of sweet-smelling herb which enable fertility." Rachel had not yet been able to bear children to Jacob, and hoped that the mandrakes would help.

But, for an anti-rationalist yeshivah bochur, far from explaining matters, this only served to complicate them further. After all, this isn’t just an ordinary person that we are talking about, but Rachel, wife of Jacob, one of the matriarchs and a righteous person of the highest stature. Surely she was fully aware that it was God Who was withholding children from her rather than any physical problem! And it was surely just as clear that her salvation would be through prayer, not through fertility drugs!

But Rav Yerucham Levovitz explained the Seforno in a way that transformed my attitude. He explains that natural law is not to be seen as conflicting with God’s authority. Just the opposite — it is a manifestation of His wisdom. God doesn't just make things happen arbitrarily; there is a system of cause-and-effect. It is important to recognize, says Rav Yerucham, that this is also true of spirituality - one's deeds, words and even thoughts have an effect. If a person does not see the system of cause-and-effect in nature, he will not see it in his spiritual life. If there is no derech eretz, no acknowledgment of a system to the world, then there is no Torah.

It took a while for me to fully absorb this message. Initially, when I recorded it in my youthful and primitive book Second Focus, I still wrote that Rachel's usage of a fertility drugs was in no way a cause of her having children, just a merit. But Rav Yerucham had set me on the path to Maimonidean rationalism. I had begun to see that natural law is not a negative phenomenon that just exists to give us free will, but rather it is the proper way for God to run the world. And when I eventually applied that line of thinking to the development of the universe and of life, I realized that it would be appropriate for God to have done this via an orderly system of natural law, rather than zapping things into existence.

So, that's how I came to a rationalist view of nature - from a marvelous mandrake and a mashgiach of Mir!

Published on November 07, 2013 13:06

November 5, 2013

A Mistake In Science, Or A Mistake In Torah?

Continuing our review of Rabbi Meiselman's book, I would like to draw attention to an astonishing principle that he asserts. First, though, for the benefit of those who have not read the book and are confused about his overall approach, a few words of explanation. Rabbi Meiselman's major thesis is that "if Chazal make a definitive statement, whether regarding halachah or realia, it means that they know it to be unassailable" (p. 107). But, says Rabbi Meiselman, if they make a tentative statement, it could potentially be in error.

(While Rabbi Meiselman does not remotely prove his assertion that any definitive statement of Chazal about the natural world is unassailable, we will not dwell upon that for now.)

Although Rabbi Meiselman concedes that tentative statements of the Sages could be in error, he insists that we ourselves are not allowed to draw this conclusion:

Let us first consider the case in Pesachim, where it is Rabbi Yehudah HaNasi that concedes that the gentiles are correct with regard to the sun's path at night. That would initially seem to fit well with Rabbi Meiselman's principle. But let us suppose that Rabbi Yehudah HaNasi would not have conceded to the gentiles (or let us suppose that that part of the Gemara would have been lost). According to Rabbi Meiselman, it would then have been forbidden for us to say that the sun goes on the other side of the world at night!

Rabbi Meiselman does not even seem to observe his own methodology with other cases that he discusses later in the book. For example, with regard to the mouse that is generated from dirt, Rabbi Meiselman says that Chazal were not definitively stating that it exists, only tentatively exploring the possibility. It is therefore, he says, not problematic to point out that there is no such creature. But Chazal never said that Chazal were wrong! Isn't he contravening his own methodology, quoted above? Is he not being melagleg al divrei Chachamim by his own definition?

Things get even more strange and problematic when we read more about Rabbi Meiselman's approach regarding cases where Chazal were speaking tentatively and were in error:

Furthermore, how can this be reconciled with what Rabbi Meiselman writes elsewhere in the book? The most obvious example of Rabbi Meiselman's principle is the case in Pesachim. So, Rabbi Meiselman is telling us, the Sages who believed that the sun goes behind the sky at night were not following the contemporary Babylonian cosmology; instead, they were solely, albeit tentatively, deriving their position from the Torah. It is extremely difficult to reconcile this with what Rabbi Meiselman writes in the chapter about Pesachim, where he is arguing that the Sages of Israel were wrong precisely because they could not obtain their knowledge from the Torah (and to which I responded that elsewhere in the Gemara, we see that they did relate their cosmological view to Scriptural exegesis).

Those of us who follow the rationalist Rishonim and Acharonim, and who do not subscribe to Rabbi Meiselman's assertion that only Chazal can point to errors in Chazal's statements, will observe a remarkable phenomenon. There are numerous cases where Chazal's statements about the natural world are incorrect, whether they are referring to salamanders spontaneously generating from fire, seven-month fetuses being more viable than eight-month fetuses, the kidneys providing counsel, hyenas changing gender, etc. According to Rabbi Meiselman, we are not allowed to declare any of these to be mistaken; and even if they were mistaken, they were mistakes in the Sages' interpretation of Torah - they were not presentations of the mistaken science of their era and had no connection to it. But where does the Torah speak about salamanders coming from fire or hyenas changing gender? And isn't it an extraordinary coincidence that those insights which turn out to be in error are so often identical to the errors made by non-Jewish scientists of that era?

(While Rabbi Meiselman does not remotely prove his assertion that any definitive statement of Chazal about the natural world is unassailable, we will not dwell upon that for now.)

Although Rabbi Meiselman concedes that tentative statements of the Sages could be in error, he insists that we ourselves are not allowed to draw this conclusion:

"The human mind - even that of a Tanna or Amora - has limitations... Sometimes even a great scholar may err... Nevertheless, the prerogative of declaring any of their teachings mistaken is granted to them, not to us. For anyone other than Chazal themselves, questioning their conclusions is called being melagleg al divrei Chachamim - "mocking of the words of the Sages" - a crime with very serious consequences." (p. 108)In this post, I will not deal with the difficulty of reconciling this with countless topics from the Gemara and sources from Rishonim and Acharonim that are not mentioned in Rabbi Meiselman's book. It is sufficient for now to discuss only the difficulty of reconciling this with other topics in Rabbi Meiselman's own book.

Let us first consider the case in Pesachim, where it is Rabbi Yehudah HaNasi that concedes that the gentiles are correct with regard to the sun's path at night. That would initially seem to fit well with Rabbi Meiselman's principle. But let us suppose that Rabbi Yehudah HaNasi would not have conceded to the gentiles (or let us suppose that that part of the Gemara would have been lost). According to Rabbi Meiselman, it would then have been forbidden for us to say that the sun goes on the other side of the world at night!

Rabbi Meiselman does not even seem to observe his own methodology with other cases that he discusses later in the book. For example, with regard to the mouse that is generated from dirt, Rabbi Meiselman says that Chazal were not definitively stating that it exists, only tentatively exploring the possibility. It is therefore, he says, not problematic to point out that there is no such creature. But Chazal never said that Chazal were wrong! Isn't he contravening his own methodology, quoted above? Is he not being melagleg al divrei Chachamim by his own definition?

Things get even more strange and problematic when we read more about Rabbi Meiselman's approach regarding cases where Chazal were speaking tentatively and were in error:

"...Whether Chazal were speaking definitively or tentatively, they were never - in the opinion of these authorities - merely presenting contemporary science (note - in a footnote, he says that practical medicine may be an exception). They were presenting insights about reality derived from the Torah... Consequently, even when a tentative statement of Chazal is in error, it is not an error in science but an error in the interpretation of the Torah." (pp. 107-8)This is remarkable! Remember how the Gedolim came crashing down upon me for saying that Chazal made errors in science, due to their following the scientists of their era? Isn't it much, much worse to say that Chazal were actually making errors in Torah rather than in science?!

Furthermore, how can this be reconciled with what Rabbi Meiselman writes elsewhere in the book? The most obvious example of Rabbi Meiselman's principle is the case in Pesachim. So, Rabbi Meiselman is telling us, the Sages who believed that the sun goes behind the sky at night were not following the contemporary Babylonian cosmology; instead, they were solely, albeit tentatively, deriving their position from the Torah. It is extremely difficult to reconcile this with what Rabbi Meiselman writes in the chapter about Pesachim, where he is arguing that the Sages of Israel were wrong precisely because they could not obtain their knowledge from the Torah (and to which I responded that elsewhere in the Gemara, we see that they did relate their cosmological view to Scriptural exegesis).

Those of us who follow the rationalist Rishonim and Acharonim, and who do not subscribe to Rabbi Meiselman's assertion that only Chazal can point to errors in Chazal's statements, will observe a remarkable phenomenon. There are numerous cases where Chazal's statements about the natural world are incorrect, whether they are referring to salamanders spontaneously generating from fire, seven-month fetuses being more viable than eight-month fetuses, the kidneys providing counsel, hyenas changing gender, etc. According to Rabbi Meiselman, we are not allowed to declare any of these to be mistaken; and even if they were mistaken, they were mistakes in the Sages' interpretation of Torah - they were not presentations of the mistaken science of their era and had no connection to it. But where does the Torah speak about salamanders coming from fire or hyenas changing gender? And isn't it an extraordinary coincidence that those insights which turn out to be in error are so often identical to the errors made by non-Jewish scientists of that era?

Published on November 05, 2013 13:07

November 4, 2013

Anti-Rationalist Mania

In a previous post, "Rabbi Meiselman Tries To Hide From The Sun," I referred to the topic of the sun's path at night - the single most powerful proof for the legitimacy of the rationalist approach regarding Chazal and science - in which all the Rishonim, as well as many Acharonim, accept that the Gemara is recording a dispute about the sun’s path at night; and the majority of Rishonim, as well as many Acharonim, accept that the Sages of Israel were incorrect. I demonstrated that when Rabbi Meiselman discusses this topic in his new book, he engages in concealment and obfuscation of the nature of the discussion and confusion of issues, and I showed that his attempt to render the topic irrelevant is flawed.

All this could not go unanswered, of course, and so in the comments to the post, some people argued back. One character, too afraid to use his real name and posting under the moniker "Observer," did not actually respond to any of my points, but repeatedly insisted that I am not remotely the Torah or science scholar that Rabbi Meiselman is, that no talmid chacham agrees with me, that I don't know how to learn the Rishonim, that I have no idea what the rakia is, that nobody cares what I say, etc., etc.

The strangest aspect of his comment is that even Rabbi Meiselman himself, at the end of all his attempts to obfuscate and mislead people in this section, is forced to admit that the Rishonim mean exactly what I say they mean! I quote: "...Chazal's self assuredness did not prevent them from admitting error when confronted with what they recognized as truth. According to most Rishonim... the passage in Pesachim is an illustration of just such an admission" (p. 148). Rabbi Meiselman attempts to argue that this is irrelevant to the larger Torah-science issue, for reasons that I have and shall further discuss, but he concedes that most Rishonim do indeed say that the Chachmei Yisrael mistakenly believed the sun to go behind the sky at night - exactly as I stated!

It's truly fascinating that in their zeal to discredit me, people will argue that I am wrong even when their heroes say exactly what I am saying!

Another response came from Rabbi Dovid Kornreich, a disciple of Rabbi Meiselman whose input is acknowledged in the book, and who is known in the blogosphere by his moniker "Freelance Kiruv Maniac." In response to my charge that Rabbi Meiselman had attempted to conceal the straightforward meaning of the Gemara, Kornreich claimed that there is no straightforward meaning!

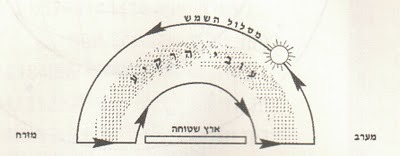

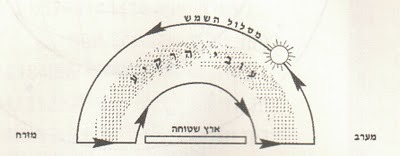

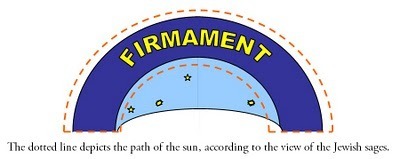

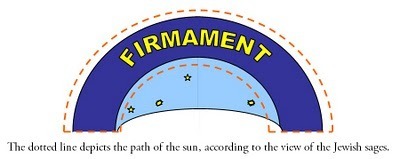

Of course, this claim is nothing short of ludicrous. There indeed is a straightforward meaning. It's the literal translation of the Gemara. It's the explanation given by Rashi. It's the explanation given by countless Rishonim and Acharonim. It's the elucidation given by Artscroll and Soncino and Koren and Shas Lublin (Machon HaMaor), which gives the illustration shown here:

And, as noted above, even Rabbi Meiselman eventually has to acknowledge that this is the understanding of the Rishonim!

Kornreich's second claim was that the Rishonim give a host of different explanations regarding the nature of the rakia (firmament). However, this is entirely irrelevant. First of all, some of those were not explanations of Chazal's view of the rakia, but rather of these Rishonim's own understanding of the rakia of the Torah. Second, this is a red herring. It makes no difference what they thought the rakia was made out of. All that matters is that they accepted that Chazal mistakenly believed the sun to change direction at night and go behind the sky, as opposed to the correct view of the gentiles that it passes on the far side of the earth.

Kornreich attempts to argue that the Rishonim were not explaining the Gemara, just extracting the halachic relevance that the sun goes on the other side of the world at night, as per the view of the Gentiles. The problem is that if the Gentile scholars were correct about the sun going on the other side of the world at night, then the Sages of Israel were ipso facto saying that the sun does not go on the other side of the world at night and were incorrect. So Kornreich issues the incredible claim that the Rishonim held there to be no actual argument between the Sages of Israel and the gentiles: the Sages of Israel were talking about a metaphysical reality, wheres the gentiles were talking about the physical world. In other words, even though the Gemara phrases it as a dispute about cosmology, and R. Yehudah HaNasi chooses the opinion of the gentile scholars, there was actually no dispute about cosmology! This would be a fantastically far-fetched explanation to propose for the Gemara, but Kornreich goes even further and claims that the Rishonim held this view but made no mention of it! (And, once again, Kornreich is contradicting his own rebbe, Rabbi Meiselman, who eventually conceded that according to most Rishonim, this is an example of Chazal being in error.)

Moving to the Acharonim, Kornreich claims that that "by observing the extreme variety of their interpretations, one can tell this gemara appears to be far from straightforward." Actually, by observing the extreme variety of some of their interpretations, and contrasting it with the complete lack of variety of explanations among the Rishonim, one can reach a different conclusion: that the Gemara has a very straightforward meaning, which the Rishonim were fine with, but which many Acharonim were deeply uncomfortable with.

Kornreich argues that since R. Yehudah HaNasi agreed with the gentiles, it's not a case of saying "Chazal were wrong." But how is that at all relevant? The point is that several sages were incorrect about a basic fact of the natural world, due to their not having a divine source for this knowledge.

This brings us back to the way in which Rabbi Meiselman attempts to render this Gemara irrelevant to the rationalist approach. In the previous post, I noted why his attempt fails; there is no basis for concluding that Chazal's views on the sun's path at night were any different from their views on other aspects of the natural world. (In fact, unlike some of their statements about the natural world, Chazal related their view on the sun's path at night, and of the firmament, to pesukim. In cases where they did not relate their view to pesukim, they would be all the more ready to concede error.)

Rabbi Meiselman, followed by Kornreich, offers two sources to show that one cannot extrapolate from the sun's path at night to other cases. One is that Rabbi Yehoshua engages in a Scriptural exegesis in order to determine the gestation period of a snake. But what does this show? After all, the Sages also engaged in Scriptural exegesis in order to determine the sun's path at night. It might be different if we could show that Rabbi Yehoshua's exegesis was actually correct, but we can't even do that, forcing Rabbi Meiselman to claim that Rabbi Yehoshua was referring a particular and unknown species (which the Gemara, misleadingly, referred to with the generic term nachash).

Rabbi Meiselman/ Kornreich's second source is Rambam, who, when discussing Chazal's errors regarding astronomy, says that they lost the original correct Torah-based traditions in this area. For some inexplicable reason, Rabbi Meiselman (and Kornreich even more explicitly) takes this to mean that in areas where Chazal made statements about the natural world with no indication of uncertainty, these were based on the Torah and are infallible. Korneich claims that "The exception proves the rule." No, all it proves is that Rambam believed that the Jewish People originally had correct Torah-based traditions regarding astronomy (which is particularly religiously significant, and which is hinted to in a verse about the Bnei Yissacher). It proves nothing at all about Rambam believing that they had correct Torah-based traditions in areas of the natural sciences such as zoology. On the contrary; if they lacked Torah-based knowledge for something as basic and religiously significant as where the sun goes at night, all the more so did they lack Torah-based knowledge for obscure and largely irrelevant matters such as zoology.

But, to return to the points above, what are we to make of Observer and Kornreich insisting that I am wrong, even on points in which Rabbi Meiselman eventually concedes the exact same thing? Is it that the ultimate goal is not to say that Chazal were right or even that Rabbi Meiselman is right, but rather to say that Slifkin is wrong? But surely the only drive for that is precisely because I said that Chazal and Rabbi Meiselman are wrong? How does it make sense that if I am wrong, then ipso facto Rabbi Meiselman is right and Chazal are right, if he's agreeing with me that Chazal were wrong? I guess people get carried away with their anti-rationalist mania.

All this could not go unanswered, of course, and so in the comments to the post, some people argued back. One character, too afraid to use his real name and posting under the moniker "Observer," did not actually respond to any of my points, but repeatedly insisted that I am not remotely the Torah or science scholar that Rabbi Meiselman is, that no talmid chacham agrees with me, that I don't know how to learn the Rishonim, that I have no idea what the rakia is, that nobody cares what I say, etc., etc.

The strangest aspect of his comment is that even Rabbi Meiselman himself, at the end of all his attempts to obfuscate and mislead people in this section, is forced to admit that the Rishonim mean exactly what I say they mean! I quote: "...Chazal's self assuredness did not prevent them from admitting error when confronted with what they recognized as truth. According to most Rishonim... the passage in Pesachim is an illustration of just such an admission" (p. 148). Rabbi Meiselman attempts to argue that this is irrelevant to the larger Torah-science issue, for reasons that I have and shall further discuss, but he concedes that most Rishonim do indeed say that the Chachmei Yisrael mistakenly believed the sun to go behind the sky at night - exactly as I stated!

It's truly fascinating that in their zeal to discredit me, people will argue that I am wrong even when their heroes say exactly what I am saying!

Another response came from Rabbi Dovid Kornreich, a disciple of Rabbi Meiselman whose input is acknowledged in the book, and who is known in the blogosphere by his moniker "Freelance Kiruv Maniac." In response to my charge that Rabbi Meiselman had attempted to conceal the straightforward meaning of the Gemara, Kornreich claimed that there is no straightforward meaning!

Of course, this claim is nothing short of ludicrous. There indeed is a straightforward meaning. It's the literal translation of the Gemara. It's the explanation given by Rashi. It's the explanation given by countless Rishonim and Acharonim. It's the elucidation given by Artscroll and Soncino and Koren and Shas Lublin (Machon HaMaor), which gives the illustration shown here:

And, as noted above, even Rabbi Meiselman eventually has to acknowledge that this is the understanding of the Rishonim!

Kornreich's second claim was that the Rishonim give a host of different explanations regarding the nature of the rakia (firmament). However, this is entirely irrelevant. First of all, some of those were not explanations of Chazal's view of the rakia, but rather of these Rishonim's own understanding of the rakia of the Torah. Second, this is a red herring. It makes no difference what they thought the rakia was made out of. All that matters is that they accepted that Chazal mistakenly believed the sun to change direction at night and go behind the sky, as opposed to the correct view of the gentiles that it passes on the far side of the earth.

Kornreich attempts to argue that the Rishonim were not explaining the Gemara, just extracting the halachic relevance that the sun goes on the other side of the world at night, as per the view of the Gentiles. The problem is that if the Gentile scholars were correct about the sun going on the other side of the world at night, then the Sages of Israel were ipso facto saying that the sun does not go on the other side of the world at night and were incorrect. So Kornreich issues the incredible claim that the Rishonim held there to be no actual argument between the Sages of Israel and the gentiles: the Sages of Israel were talking about a metaphysical reality, wheres the gentiles were talking about the physical world. In other words, even though the Gemara phrases it as a dispute about cosmology, and R. Yehudah HaNasi chooses the opinion of the gentile scholars, there was actually no dispute about cosmology! This would be a fantastically far-fetched explanation to propose for the Gemara, but Kornreich goes even further and claims that the Rishonim held this view but made no mention of it! (And, once again, Kornreich is contradicting his own rebbe, Rabbi Meiselman, who eventually conceded that according to most Rishonim, this is an example of Chazal being in error.)

Moving to the Acharonim, Kornreich claims that that "by observing the extreme variety of their interpretations, one can tell this gemara appears to be far from straightforward." Actually, by observing the extreme variety of some of their interpretations, and contrasting it with the complete lack of variety of explanations among the Rishonim, one can reach a different conclusion: that the Gemara has a very straightforward meaning, which the Rishonim were fine with, but which many Acharonim were deeply uncomfortable with.

Kornreich argues that since R. Yehudah HaNasi agreed with the gentiles, it's not a case of saying "Chazal were wrong." But how is that at all relevant? The point is that several sages were incorrect about a basic fact of the natural world, due to their not having a divine source for this knowledge.

This brings us back to the way in which Rabbi Meiselman attempts to render this Gemara irrelevant to the rationalist approach. In the previous post, I noted why his attempt fails; there is no basis for concluding that Chazal's views on the sun's path at night were any different from their views on other aspects of the natural world. (In fact, unlike some of their statements about the natural world, Chazal related their view on the sun's path at night, and of the firmament, to pesukim. In cases where they did not relate their view to pesukim, they would be all the more ready to concede error.)

Rabbi Meiselman, followed by Kornreich, offers two sources to show that one cannot extrapolate from the sun's path at night to other cases. One is that Rabbi Yehoshua engages in a Scriptural exegesis in order to determine the gestation period of a snake. But what does this show? After all, the Sages also engaged in Scriptural exegesis in order to determine the sun's path at night. It might be different if we could show that Rabbi Yehoshua's exegesis was actually correct, but we can't even do that, forcing Rabbi Meiselman to claim that Rabbi Yehoshua was referring a particular and unknown species (which the Gemara, misleadingly, referred to with the generic term nachash).

Rabbi Meiselman/ Kornreich's second source is Rambam, who, when discussing Chazal's errors regarding astronomy, says that they lost the original correct Torah-based traditions in this area. For some inexplicable reason, Rabbi Meiselman (and Kornreich even more explicitly) takes this to mean that in areas where Chazal made statements about the natural world with no indication of uncertainty, these were based on the Torah and are infallible. Korneich claims that "The exception proves the rule." No, all it proves is that Rambam believed that the Jewish People originally had correct Torah-based traditions regarding astronomy (which is particularly religiously significant, and which is hinted to in a verse about the Bnei Yissacher). It proves nothing at all about Rambam believing that they had correct Torah-based traditions in areas of the natural sciences such as zoology. On the contrary; if they lacked Torah-based knowledge for something as basic and religiously significant as where the sun goes at night, all the more so did they lack Torah-based knowledge for obscure and largely irrelevant matters such as zoology.

But, to return to the points above, what are we to make of Observer and Kornreich insisting that I am wrong, even on points in which Rabbi Meiselman eventually concedes the exact same thing? Is it that the ultimate goal is not to say that Chazal were right or even that Rabbi Meiselman is right, but rather to say that Slifkin is wrong? But surely the only drive for that is precisely because I said that Chazal and Rabbi Meiselman are wrong? How does it make sense that if I am wrong, then ipso facto Rabbi Meiselman is right and Chazal are right, if he's agreeing with me that Chazal were wrong? I guess people get carried away with their anti-rationalist mania.

Published on November 04, 2013 04:38

November 3, 2013

Various Notes and Announcements

1. Some people really hated the posts about Bet Shemesh politics. Other people greatly valued them. Some people really hate the posts about Rabbi Meiselman's book. Other people greatly value them. Please realize that different people like different things. If you don't like a particular theme that I'm dealing with, please just skip it and come back another time! (Don't forget that you can subscribe to this blog via e-mail, so as to never miss a post, and to have them all archived.) By the way, I will be interspersing my review of R. Meiselman's book with other posts.

2. This February, I will again be visiting the US for a lecture tour, to NY/NJ and LA. A major goal of this trip is to raise funds for three large projects that I am involved in: The Torah Encyclopedia of the Animal Kingdom, a documentary on the animal kingdom in Jewish Thought, and especially The Jewish Museum of Natural History. If you are able and willing to host a parlor meeting in which I would give a presentation and raise funds, please write to me.

3. Visiting Israel? You can see part of the collection for the Jewish Museum of Natural History, and enjoy a hands-on presentation about the animal kingdom in Jewish thought. A one-hour presentation, for a group of up to twelve people, is $100. For reservations, write to zoorabbi@zootorah.com with "museum visit" in the subject line.

4. Are you making aliyah? If you are doing a lift from the US to Israel, I would very much like to put some flat-pack animal cages on it for the museum (obviously I would pay for the space), that are only available in the US.

5. This coming July, I will once again be guiding a kosher safari with Torah in Motion, to South Africa, Botswana and Zimbabwe. Please write to me if you are interested in more details.

6. Several people have suggested that I join FaceBook or Twitter, to help spread my material. Thanks for the suggestion, but no! It would just be too much of a drain on my mind and my time.

2. This February, I will again be visiting the US for a lecture tour, to NY/NJ and LA. A major goal of this trip is to raise funds for three large projects that I am involved in: The Torah Encyclopedia of the Animal Kingdom, a documentary on the animal kingdom in Jewish Thought, and especially The Jewish Museum of Natural History. If you are able and willing to host a parlor meeting in which I would give a presentation and raise funds, please write to me.

3. Visiting Israel? You can see part of the collection for the Jewish Museum of Natural History, and enjoy a hands-on presentation about the animal kingdom in Jewish thought. A one-hour presentation, for a group of up to twelve people, is $100. For reservations, write to zoorabbi@zootorah.com with "museum visit" in the subject line.

4. Are you making aliyah? If you are doing a lift from the US to Israel, I would very much like to put some flat-pack animal cages on it for the museum (obviously I would pay for the space), that are only available in the US.

5. This coming July, I will once again be guiding a kosher safari with Torah in Motion, to South Africa, Botswana and Zimbabwe. Please write to me if you are interested in more details.

6. Several people have suggested that I join FaceBook or Twitter, to help spread my material. Thanks for the suggestion, but no! It would just be too much of a drain on my mind and my time.

Published on November 03, 2013 04:29

October 31, 2013

Rabbi Meiselman Tries To Hide From The Sun

Part III of a review of Rabbi Moshe Meiselman's Torah, Chazal and Science (continued from part II)

(This post is a long one, but it's important, since it addresses the first and only attempt to refute the most powerful demonstration of the legitimacy of the rationalist approach to Chazal and science. You might want to print it out and read it on Shabbos. And, of course, you might want to share it with any readers of Rabbi Meiselman's book.)

I. The Most Crucial Topic

As I have noted on many occasions, in any discussion about Chazal (the Sages) and science, the single most crucial section of the Talmud is that regarding the sun’s path at night, which I discussed at length in a monograph. The Talmud records a dispute between the Sages of Israel and the gentile scholars regarding where the sun goes when it sets in the evening. (This follows an earlier and more complex argument about the relative motions of the celestial sphere and the constellations, which is not relevant to our discussion.) The Sages of Israel believed that the sun changes direction at night to go back behind the sky (which was believed to be an opaque “firmament”), whereas the gentile scholars believed that the sun continues its path to pass on the far side of the world (which we now know to be correct). The Talmud continues to record that Rabbi Yehudah HaNasi observed that the gentile scholars appear to be correct. All the Rishonim, as well as many Acharonim, accept that the Gemara is recording a dispute about the sun’s path at night. The majority of Rishonim, as well as many Acharonim, accept that the Sages of Israel were incorrect.

As I have noted on many occasions, in any discussion about Chazal (the Sages) and science, the single most crucial section of the Talmud is that regarding the sun’s path at night, which I discussed at length in a monograph. The Talmud records a dispute between the Sages of Israel and the gentile scholars regarding where the sun goes when it sets in the evening. (This follows an earlier and more complex argument about the relative motions of the celestial sphere and the constellations, which is not relevant to our discussion.) The Sages of Israel believed that the sun changes direction at night to go back behind the sky (which was believed to be an opaque “firmament”), whereas the gentile scholars believed that the sun continues its path to pass on the far side of the world (which we now know to be correct). The Talmud continues to record that Rabbi Yehudah HaNasi observed that the gentile scholars appear to be correct. All the Rishonim, as well as many Acharonim, accept that the Gemara is recording a dispute about the sun’s path at night. The majority of Rishonim, as well as many Acharonim, accept that the Sages of Israel were incorrect.

Here, then, is the definitive demonstration that there is a mainstream approach of saying that Chazal’s knowledge about the natural world was not divine in origin, and is potentially errant. But Rabbi Meiselman, on the other hand, says that whenever Chazal make a definite statement about the natural world, or one that is based upon Scriptural exegesis, they are correct. He insists that it is forbidden to say otherwise, and his book is dedicated to rebutting, insulting, disparaging and condemning those who take a different view. How, then, does Rabbi Meiselman deal with this topic?

II. What Did Chazal Say, And What Did They Mean? Rabbi Meiselman Won’t Tell You

Rabbi Meiselman discusses this topic over six pages in the second part of chapter ten. He quotes the Gemara, but does not translate the word “rakia.” In a footnote, he accounts for this by saying that although the standard translation is “firmament,” the precise meaning is a subject of debate among the commentators. In fact, 95% of the commentators, and 100% of the Rishonim, agree that it means “firmament.” One can almost always find someone who disagrees with a conventional translation, but that’s not a reason not to use it, unless one is deliberately trying to either distort the picture regarding the situation with the commentaries, or obfuscate the entire discussion by not explaining what the Gemara is about.

Rabbi Meiselman appears to be trying to do both. He begins his explanation of the Gemara, in a section entitled “What Did Chazal Mean?” by stating that “The cryptic nature of these discussions has caused them to be given a variety of explanations.” In fact, the discussion regarding the sun's path at night is not cryptic in the least; the Talmud’s words are clear and straightforward. It only has a variety of explanations post-15th century, and the only reason for this is that many people were uncomfortable with Chazal having been mistaken on something that appears so basic to modern audiences. Rabbi Meiselman writes that “According to many commentaries they are not to be taken at face value at all.” Yes, but not according to any of the Rishonim.

Almost incredibly, Rabbi Meiselman does not make any mention of the straightforward meaning of this Gemara, adopted by all the Rishonim: that the sun changes direction to travel behind an opaque solid firmament at night. Nowhere does he present a simple, straightforward explanation of what the Gemara is talking about (or even any explanation). In a book spanning eight hundred pages, he couldn’t even spend a single paragraph explaining the meaning of the most crucial passage in the entire Torah-science discussion?! Nor does he quote any of the Rishonim and Acharonim who explain the Gemara according to its straightforward meaning. Such a long book, so many hundreds and hundreds of sources quoted, including many that are barely relevant, but he does not quote any of the Rishonim on the most fundamental topic in the entire discussion!

After making the misleading claim that according to many commentaries the Talmud is not intended to be literal, Rabbi Meiselman states that “But even among those who take them literally, explanations vary.” He proceeds to cite “The Rama, for instance,” who has a highly creative reinterpretation of the Gemara. This reinforces the impression that there is only a small minority view that explains the Gemara according to its plain meaning – whereas the fact is that all the Rishonim, without exception, as well as many Acharonim, explain it in this way.

Rabbi Meiselman then spends a paragraph discussing geocentrism and heliocentrism. But this only relates to the earlier, more complex and irrelevant discussion in the Gemara about the celestial sphere and the constellations. Rabbi Meiselman avoids any further discussion of the passage in the Gemara regarding the sun’s path at night, never having once explained either its straightforward meaning or indeed any meaning. And thus he concludes the section entitled “What Did Chazal Mean?” - without having even attempted to answer that question.

III. Rabbi Meiselman Mistakenly Attributes Mistaken Beliefs To The Rishonim

The next section is entitled “When The Commentaries Are Mistaken.” Here is where things get very strange. Throughout the rest of the book, while there is ample basis for questioning Rabbi Meiselman’s intellectual honesty and epistemology, there is no doubt that he is a highly intelligent Torah scholar. But in this section, Rabbi Meiselman appears to simply not understand what is going on in the commentaries.

Rabbi Meiselman states that the Rama and his colleagues (who attempted to explain that Chazal were not mistaken) were explaining the Gemara to the best of their abilities, but they never intended to chain Chazal’s words to their own understanding. If their grasp of science was wrong, they would prefer Chazal to be explained differently. He proceeds to state:

It should be noted that Rabbi Meiselman provides no support whatsoever for his emphatic assertion that the Rishonim, when commented upon such sugyos, only intended their explanations to be tentative, in contrast to their explanations of other sugyos. (Nor does he explain why this would only apply to the Rishonim’s explanation of Chazal’s statements about the natural world, and not to Chazal’s explanations of the Torah’s statements about the natural world.) And since he provides no support for it, and there is no indication for it in the words of the Rishonim themselves, there is no reason to accept it as being true.

But there is a more basic problem with Rabbi Meiselman’s approach here. Put quite simply, he doesn’t understand what the whole discussion is about with regard to this passage in the Talmud. True, if you’re talking about the topic of spontaneous generation, you can say that the Rishonim explained Chazal in terms of their own erroneous beliefs. And if you’re talking about the Rama’s defense of Chazal’s statements about cosmology, you can say that he explained them in terms of his own erroneous beliefs. But you can’t say this if you’re talking about the Rishonim’s discussion of Chazal’s statements about the sun’s path at night. Here, the Rishonim do not “interpret this passage in terms of astronomical theories that were accepted in their day.” They explain it as referring to a mistaken and obsolete view!

In other words, whereas Rabbi Meiselman says that “if the interpreters of Chazal held erroneous beliefs, it does not at all follow that Chazal did as well,” he is fundamentally misunderstanding what is going on. This is not like the discussions of spontaneous generation. In this case, the interpreters of Chazal did not hold erroneous beliefs – they correctly believed that the sun goes on the other side of the world at night, not behind the firmament. They were stating that Chazal held erroneous beliefs.

IV. A Failed Attempt To Render This Topic Irrelevant

In the next section, entitled “Acknowledging the Truth,” Rabbi Meiselman backpedals from his earlier misrepresentation. He starts off by admitting that “some” commentaries take the Gemara at face value, according to which Chazal acknowledged that they had erred and the truth lay with the gentiles; at the end of the section, he finally himself acknowledges the truth, that this position is held by “most Rishonim other than Rabbeinu Tam.”

However, acknowledging that most Rishonim held Chazal to have been mistaken puts Rabbi Meiselman in a very awkward position, since it would refute his entire approach. And so he attempts to render this case irrelevant. He stresses – and this is the goal of this section - that “assuming that the Jewish sages actually retracted,” they did so despite their utter certitude that in general, their wisdom was vastly superior to that of the Gentiles, due to their having derived it from the Torah. He proceeds to claim that the fact that Chazal discussed cosmology with the Gentile scholars “means that they had no precise mesorah on this particular topic,” and that “nor were they able to extract the desired information from the Torah.” But, he adamantly insists, in every other case, where Chazal do not inform us that they are uncertain, or when they derive their knowledge from the Torah, we can rest assured that they are correct, and “they carry the full authority of Torah shebaal Peh.”

However, there are three problems with all this. First is that the fact that the Gemara records a discussion with the gentile scholars does not mean that Chazal are informing us that they are uncertain. It just means that this was an important topic in which the gentile scholars had a very different opinion and turned out to be correct. The Gemara does not record discussions with the gentile scholars about spontaneous generation, because the gentile scholars had the same view as Chazal regarding spontaneous generation.

Second is that the error made in Pesachim is with regard to something extremely basic. Whether the sun doubles back at night to go behind a solid firmament, or continues to pass around the far side of the earth, is a very fundamental part of cosmology. (It is also taken to have substantial halachic ramifications.) If Chazal did not even know something so fundamental, and could not figure it out from the Torah even though the Torah has a lot to say about cosmology, and even though the non-Jews were able to figure it out (as Rabbi Yehudah HaNasi acknowledges), then why on earth would Chazal be authoritative in much more arcane areas of knowledge (such as zoology), in which the Torah has nothing to say and in which the gentiles were likewise unaware of the reality?

But much more problematic than both of these is that Rabbi Meiselman’s premise is fundamentally flawed. Chazal did relate their views on cosmology to the Torah! This is not mentioned on this page in Pesachim, but it is mentioned on an earlier page in Pesachim, as well as in Bava Basra and in the Midrash. In Bava Basra, one of the Sages posits that the sun makes a 180 degree reversal in the evening, and another of the Sages states that it turns 90 degrees to the side, basing this on a passuk. In the earlier page in Pesachim and in the Midrash, Chazal talk about the thickness and substance of the firmament, basing their discussion on pesukim. (This also renders futile an earlier attempt by Rabbi Meiselman to get out of this whole problem, by suggesting that the "scholars of Israel" in Pesachim might not have been Sages.)

How did Rabbi Meiselman not know any of this? Did he fail to do basic research on this topic? Did he not read my monograph that he is attempting to rebut? In any case, it neatly destroys his excuse as to why this would be the only case in which Chazal were mistaken. Consequently, the case of the sun’s path at night remains as a fundamental disproof of Rabbi Meiselman’s approach regarding Chazal and science.

V. Conclusion

The bottom line is that Rabbi Meiselman’s discussion of this topic – the most basic topic in any Torah-science discussion – is deliberately vague, extremely confused, poorly researched, and self-contradictory. Although at the end he concedes that most Rishonim held Chazal to have erred in this matter (albeit with a flawed explanation as to why this case is unique), earlier he claims with regard to this topic that “The possibility that Chazal were in error was never an option for the Baalei HaMesorah” (p. 145). In fact, the vast majority of Rishonim, as well as countless Acharonim, held that Chazal were indeed in error – even though they based their view on the Torah. The inescapable conclusion is that Rabbi Meiselman is misrepresenting the nature of the Baalei HaMesorah.

(This post is a long one, but it's important, since it addresses the first and only attempt to refute the most powerful demonstration of the legitimacy of the rationalist approach to Chazal and science. You might want to print it out and read it on Shabbos. And, of course, you might want to share it with any readers of Rabbi Meiselman's book.)

I. The Most Crucial Topic

As I have noted on many occasions, in any discussion about Chazal (the Sages) and science, the single most crucial section of the Talmud is that regarding the sun’s path at night, which I discussed at length in a monograph. The Talmud records a dispute between the Sages of Israel and the gentile scholars regarding where the sun goes when it sets in the evening. (This follows an earlier and more complex argument about the relative motions of the celestial sphere and the constellations, which is not relevant to our discussion.) The Sages of Israel believed that the sun changes direction at night to go back behind the sky (which was believed to be an opaque “firmament”), whereas the gentile scholars believed that the sun continues its path to pass on the far side of the world (which we now know to be correct). The Talmud continues to record that Rabbi Yehudah HaNasi observed that the gentile scholars appear to be correct. All the Rishonim, as well as many Acharonim, accept that the Gemara is recording a dispute about the sun’s path at night. The majority of Rishonim, as well as many Acharonim, accept that the Sages of Israel were incorrect.

As I have noted on many occasions, in any discussion about Chazal (the Sages) and science, the single most crucial section of the Talmud is that regarding the sun’s path at night, which I discussed at length in a monograph. The Talmud records a dispute between the Sages of Israel and the gentile scholars regarding where the sun goes when it sets in the evening. (This follows an earlier and more complex argument about the relative motions of the celestial sphere and the constellations, which is not relevant to our discussion.) The Sages of Israel believed that the sun changes direction at night to go back behind the sky (which was believed to be an opaque “firmament”), whereas the gentile scholars believed that the sun continues its path to pass on the far side of the world (which we now know to be correct). The Talmud continues to record that Rabbi Yehudah HaNasi observed that the gentile scholars appear to be correct. All the Rishonim, as well as many Acharonim, accept that the Gemara is recording a dispute about the sun’s path at night. The majority of Rishonim, as well as many Acharonim, accept that the Sages of Israel were incorrect.Here, then, is the definitive demonstration that there is a mainstream approach of saying that Chazal’s knowledge about the natural world was not divine in origin, and is potentially errant. But Rabbi Meiselman, on the other hand, says that whenever Chazal make a definite statement about the natural world, or one that is based upon Scriptural exegesis, they are correct. He insists that it is forbidden to say otherwise, and his book is dedicated to rebutting, insulting, disparaging and condemning those who take a different view. How, then, does Rabbi Meiselman deal with this topic?

II. What Did Chazal Say, And What Did They Mean? Rabbi Meiselman Won’t Tell You

Rabbi Meiselman discusses this topic over six pages in the second part of chapter ten. He quotes the Gemara, but does not translate the word “rakia.” In a footnote, he accounts for this by saying that although the standard translation is “firmament,” the precise meaning is a subject of debate among the commentators. In fact, 95% of the commentators, and 100% of the Rishonim, agree that it means “firmament.” One can almost always find someone who disagrees with a conventional translation, but that’s not a reason not to use it, unless one is deliberately trying to either distort the picture regarding the situation with the commentaries, or obfuscate the entire discussion by not explaining what the Gemara is about.

Rabbi Meiselman appears to be trying to do both. He begins his explanation of the Gemara, in a section entitled “What Did Chazal Mean?” by stating that “The cryptic nature of these discussions has caused them to be given a variety of explanations.” In fact, the discussion regarding the sun's path at night is not cryptic in the least; the Talmud’s words are clear and straightforward. It only has a variety of explanations post-15th century, and the only reason for this is that many people were uncomfortable with Chazal having been mistaken on something that appears so basic to modern audiences. Rabbi Meiselman writes that “According to many commentaries they are not to be taken at face value at all.” Yes, but not according to any of the Rishonim.

Almost incredibly, Rabbi Meiselman does not make any mention of the straightforward meaning of this Gemara, adopted by all the Rishonim: that the sun changes direction to travel behind an opaque solid firmament at night. Nowhere does he present a simple, straightforward explanation of what the Gemara is talking about (or even any explanation). In a book spanning eight hundred pages, he couldn’t even spend a single paragraph explaining the meaning of the most crucial passage in the entire Torah-science discussion?! Nor does he quote any of the Rishonim and Acharonim who explain the Gemara according to its straightforward meaning. Such a long book, so many hundreds and hundreds of sources quoted, including many that are barely relevant, but he does not quote any of the Rishonim on the most fundamental topic in the entire discussion!

After making the misleading claim that according to many commentaries the Talmud is not intended to be literal, Rabbi Meiselman states that “But even among those who take them literally, explanations vary.” He proceeds to cite “The Rama, for instance,” who has a highly creative reinterpretation of the Gemara. This reinforces the impression that there is only a small minority view that explains the Gemara according to its plain meaning – whereas the fact is that all the Rishonim, without exception, as well as many Acharonim, explain it in this way.

Rabbi Meiselman then spends a paragraph discussing geocentrism and heliocentrism. But this only relates to the earlier, more complex and irrelevant discussion in the Gemara about the celestial sphere and the constellations. Rabbi Meiselman avoids any further discussion of the passage in the Gemara regarding the sun’s path at night, never having once explained either its straightforward meaning or indeed any meaning. And thus he concludes the section entitled “What Did Chazal Mean?” - without having even attempted to answer that question.

III. Rabbi Meiselman Mistakenly Attributes Mistaken Beliefs To The Rishonim

The next section is entitled “When The Commentaries Are Mistaken.” Here is where things get very strange. Throughout the rest of the book, while there is ample basis for questioning Rabbi Meiselman’s intellectual honesty and epistemology, there is no doubt that he is a highly intelligent Torah scholar. But in this section, Rabbi Meiselman appears to simply not understand what is going on in the commentaries.

Rabbi Meiselman states that the Rama and his colleagues (who attempted to explain that Chazal were not mistaken) were explaining the Gemara to the best of their abilities, but they never intended to chain Chazal’s words to their own understanding. If their grasp of science was wrong, they would prefer Chazal to be explained differently. He proceeds to state:

“What is true of the Rama is true of the many Rishonim and Acharonim who interpret this passage in terms of astronomical theories that were accepted in their day, but were subsequently rejected by science. It was never their intention that their explanations were definitely what Chazal meant. They were merely doing their best to understand an obscure piece of Gemara, using the most reliable scientific information available to them. When contemporary writers invoke these commentaries to show that Chazal’s knowledge was faulty they are making a simple error in logic. If the interpreters of Chazal held erroneous beliefs, it does not at all follow that Chazal did as well.”

It should be noted that Rabbi Meiselman provides no support whatsoever for his emphatic assertion that the Rishonim, when commented upon such sugyos, only intended their explanations to be tentative, in contrast to their explanations of other sugyos. (Nor does he explain why this would only apply to the Rishonim’s explanation of Chazal’s statements about the natural world, and not to Chazal’s explanations of the Torah’s statements about the natural world.) And since he provides no support for it, and there is no indication for it in the words of the Rishonim themselves, there is no reason to accept it as being true.