Amanda Desiree's Blog, page 5

August 14, 2021

Smithy Easter Eggs and Fun Facts

I infused Smithy with references to famous figures, haunted history, favorite authors and TV shows, and inside references for my friends. Here is a sampling of such Easter eggs and behind-the-scenes trivia:

The fictitious house Trevor Hall is named after a co-author of The Haunting of Borley Rectory--A Critical Survey of the Evidence (1956).

Members of the Trevor family (e.g., Victoria, David, Curtis) are named for characters from the TV show "Dark Shadows" and its creator Dan Curtis.

The fictitious house Herbert Terrace is named after the scientist who spearheaded Project Nim, an early primate language study in the 1970s.

The original owner of this house, Jonathan Herbert, is named after actor Jonathan Herbert Frid ("Dark Shadows" Seizure).

Piers Preis-Herald is named after British ghost hunter Harry Price, who investigated the haunting of Borley Rectory.

Ruby Cardini is named after the restaurant chain Ruby's Diner. I brainstormed plot and character details of Smithy while lunching one afternoon at the Redondo Beach location on the waterfront (unfortunately, this location permanently closed during the 2020 lockdown).

Wanda Karlewicz is named for my friend Teresa and actor John Karlen (born John Karlewicz) of "Dark Shadows," Daughters of Darkness, and "Cagney & Lacey" fame.

Tammy Cohen is named after a character on the TV show "Mad Men" and author Daniel Cohen, whose books about the spooky and the supernatural written for young readers were favorites from my childhood.

Wanda's fellow researchers and co-authors Judy Caswell and Roger Keene are named for my friends who passed away in 2013 and 2007, respectively.

Before the Internet took off, psychologist Philip Zimbardo sold videos or DVDs of Quiet Rage, a documentary about his notorious Stanford Prison Experiment, through a PO box in Stanford, CA. Piers's PO Box in Stamford, CT uses the same number. Piers's PO Box is fictitious (the zip code isn't even for Stamford). Quiet Rage can now be ordered online: https://www.prisonexp.org/

The Black Pearl, where Ruby celebrates her birthday, served as the exterior for the Blue Whale pub in "Dark Shadows."

The White Horse Tavern, another birthday dinner spot, is said to be haunted. A publicity photo of the dining room allegedly depicts a spirit.

Imogene Rockwell is named after Imogen Swinhoe, purportedly the spirit who haunts Cheltenham Manor in England, and artist Norman Rockwell, whose works are featured in the Museum of Illustration in Newport, RI.

Stay tuned for more trivia in the coming days!

August 4, 2021

Smithy in Newport

On a visit to Newport/Middletown, RI earlier this summer, I was thrilled to find Smithy shelved in "Local Interest" at the Barnes and Noble store.

Although the novel takes place in a fictitious Newport mansion, it also describes several real historic mansions over the course of the story and alludes to the town's history as a popular retreat for the nation's upper crust. I feel honored that Newport has welcomed Smithy welcomed as a local story.

July 19, 2021

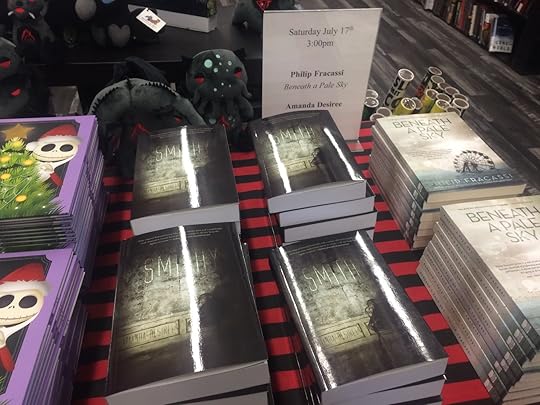

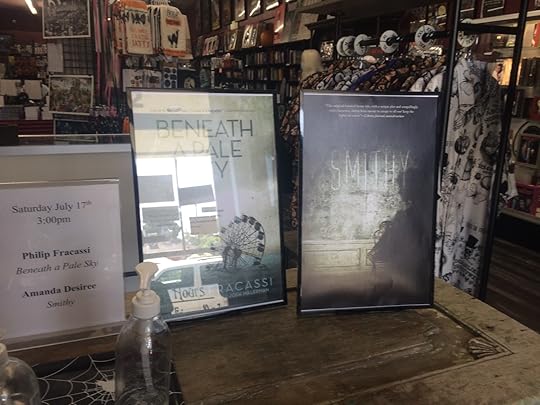

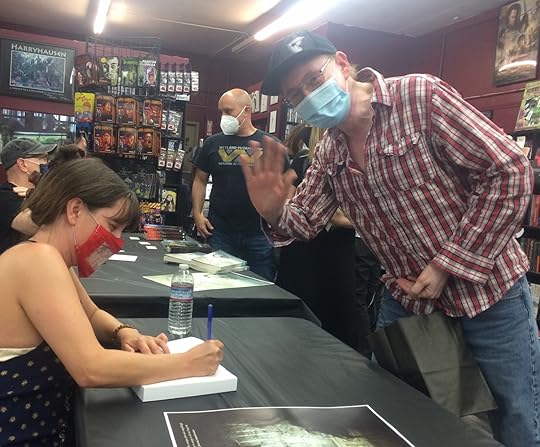

Book Signing at Dark Delicacies (July 17, 2021)

Thank you to everyone who came out over the weekend to support Smithy! Special thanks to Del Howison and everyone at Dark Delicacies for hosting this event.

July 7, 2021

"For the Love of Horror" Features Amanda Desiree

It was an honor to be interviewed by author Gwendolyn Kiste for her blog, "For the Love of Horror:" http://www.gwendolynkiste.com/Blog/for-the-love-of-horror-interview-with-amanda-desiree/

June 30, 2021

The House

“My name is Victoria Winters and my journey is beginning…a journey that will bring me to a strange, dark place, to the edge of the sea, high atop Widows’ Hill. A house called Collinwood…”

If you recognize that introduction, then you may already have guessed part of the inspiration for the house where Smithy is set.

Initially, I had contemplated setting the book in a haunted manor house in England, for those were the sorts of houses that had first stimulated my imagination. Specifically, I had decided to base my haunting on the phenomena at Borley Rectory, sometimes said to be the most haunted house in England. When I at first toyed with the idea of writing Smithy as a screenplay, I considered pitching it as a follow-up to The Woman in Black: Years after the original events unfold, a group of university students decides to rent Eel Marsh House for its ape language study, either not knowing about or not believing in the malevolent spirit alleged to haunt the house.

However, I didn’t think I could pull it off because I have never been to England. I don’t know the climate, the lingo, or the culture of England in the 1970s (when the experiment must take place). It would have bene a struggle to make the setting and characters convincing.

Still, I needed a large house, a mansion really, that would have had servants in its heyday but could have become dilapidated in the interim. And I knew just the place stateside where such a mansion might conceivably be found.

Newport, Rhode Island!

Over the past ten years, I have visited Newport for Halloween and occasionally in summer. While there, I have had the privilege of staying at Seaview Terrace (Picture 1). The present Seaview Terrace is an amalgamation of Seaview, a house originally located on the same site in the 1800s, and a Washington, D.C. estate called DuPont Circle. In 1923, the Edson Bradley family had their D.C. residence dismantled and shipped, piece by piece, to Newport, where it was grafted onto the pre-existing Seaview. The result, unveiled in July of 1925, is one of the largest, most eclectic of the Newport mansions; a place where, even after multiple visits, it’s easy to get lost among the twisting hallways connecting the vast wings.

The Carey family of New York purchased Seaview Terrace in 1974. Before then, it had served as a girls’ school and had appeared on the small screen as “Collinwood,” the setting for “Dark Shadows” (DS), a popular 1960’s soap opera featuring an otherworldly cast of vampires, werewolves, ghosts, witches and other spooks. Though the interiors of Collinwood were a soundstage in New York, the exterior was Seaview Terrace. It appears at the opening of each episode and is an iconic image for DS fans, many of whom dream of someday making a pilgrimage to RI to see the real thing.

Some years ago, the Careys became friendly with such a group of DS fans, and eventually opened their home to limited groups of fans at certain times of the year, generously allowing them to stay in the house overnight and hold DS-themed parties. It is an exhilarating and surreal experience. DVDs of DS play in the background of the festivities throughout the weekend. You can watch the house on TV and pick out the window of the same room where you’re sitting, then step outside onto the very lawn where a character just walked. When the haunting DS soundtrack echoes through the halls, one almost expects to see Quentin Collins’s malevolent ghost leering over the balcony.

I incorporated a number of the architectural features from Seaview Terrace into the construction of Trevor Hall. A tower room. Giant fireplaces. A whispering corridor. Fire escapes. An angel-face ceiling.

I also incorporated some of the ghostly activity.

Over the years, some of my friends have heard or felt another presence in their rooms. Others have reported finding toiletries strewn around the floor, or losing small items at departure time that later reappear packed in the suitcase. One friend who was alone in the house heard a terrific banging coming from the basement, where a walk-through ‘haunted house’ had been set up; she discovered that one of the animatronics (a creepy looking zombie mother and baby sitting in a rocking chair) had somehow turned itself on and was pounding against one of the basement support beams. And some experiences have been even more dramatic than that. Sy-Fy Channel’s “Ghost Hunters” series investigated Seaview Terrace in 2011 and again in 2020, reporting eerie occurrences each time.

Parties at Seaview are like a reunion of an extended fictive family. DS fans are a tight-knit bunch. We keep in touch between official gatherings and sometimes even vacation together. For the few days that we’re together again under one roof, we can renew our friendship and make memories to last through to the next year. I planted many DS-related Easter eggs throughout Smithy, hoping that my DS family, especially my Seaview-going friends, would get a kick out of the references.

Just as Seaview Terrace is an amalgamation of two different houses, so Trevor Hall is an amalgamation of Seaview Terrace and the Elms. While Seaview is a private residence, the Elms is open to tourists year-round as one of the famed Newport Mansions. It is operated by the Newport Preservation Society, which has saved many grand houses (the Breakers, the Elms, Rosecliff, Marble House, and Chateau Sur Mer (Picture 2)) from sliding into ruin as did Trevor Hall.

The Elms may not be the glitziest mansion, but I think it has the most beautiful grounds with sweeping lawns, fountains, and a number of coper beech trees. In the spring and summer, during the tourist season, the mansion offers a special behind-the-scenes tour called the “Servants’ Life Tour.” During the DS Memorial Day Weekend gathering in 2014, I took this tour with my friends Leyla and Janice (my first beta reader!) (Picture 3). We were able to go to the third floor and view the rooms where the Elms’ servants lived. Afterward, the tour moved to the rooftop where the servants took fresh air and gathered socially. From here, one has a lovely view of the ocean, the grounds, and the surrounding houses (Picture 4). When devising a backstory for my ghost, I immediately thought back to that visit to the rooftop of the Elms. If you ever get to take the Servants’ Life tour, you’ll understand why.

Finally, in choosing a name for my haunted mansion, I wanted to honor my original sources of inspiration. I was torn between Herbert Terrace (the scientist who developed the Nim Chimpsky study) and Trevor Hall (a parapsychologist who had analyzed the Borley Rectory haunting). Ultimately, I decided to use them both. Trevor Hall became the site of the Smithy study and Herbert Terrace became a neighboring mansion whose residents interact with the researchers.

The Trevor Hall mansion may only exist in fiction, but it does incorporate elements of Newport houses and Newport history. Many of the other places described in Smithy do exist and are open to the public. If you’re able to visit Newport, you can see them for yourself just as Ruby, Gail, or Tammy experience in the book.

June 15, 2021

The Ghost

I grew up surrounding myself with ghosts. As a child, my favorite books were the “True” Ghost Story series from Sterling Publishing and the many occult-themed titles by Daniel Cohen (after whom Tammy Cohen is named). I especially loved the creepy realistic covers by Lisa Falkenstern. Real Ghosts, Ghostly Terrors, The World's Most Famous Ghosts, Phone Call from a Ghost, and so on. I read and re-read the stories, committed them to memory, and re-told them for my friends: stories about the Brown Lady of Raynham Hall, and Borley Rectory the most haunted house in England, and poltergeists like the Bell Witch and the Great Amherst Mystery. Bits of each of these stories found their way into Smithy.

The Borley Rectory haunting directly inspired the book, so it provides much of the grist for the Trevor Hall haunting. The investigation of Borley Rectory was led by psychical researcher Harry Price (after whom Dr. Preis-Herald is named), who loved the spotlight and courted his share of controversy. The Borley investigation was his most notorious. Mysterious bells echoed through the house, a levitating brick was captured on film, and phantom messages addressed to Marianne (Foyster, the lady of the house) appeared on the walls. A later appraisal for the Society for Psychical Research written by Eric Dingwall, K.M. Goldney, and Trevor Hall (the inspiration behind the name of the mansion in Smithy, because Eric Dingwall is a silly name for a house) determined that most of the phenomena was due to natural causes and the rest had been faked by Price and Foyster. Nevertheless, the legend persists.

The legend of Trevor Hall is my own invention, but the name of its purported ghost, Imogene Rockwell, derives from Imogen Swinhoe, formerly the lady of Cheltenham Manor and now popularly believed to be the Woman in Black who haunts it, and from the Museum of Illustration in Newport, RI, which houses a collection of Norman Rockwell’s artwork. I say “purported” because the identity of the ghost is deliberately obscured.

Outside of celebrity ghosts like Abraham Lincoln or Marilyn Monroe, most spirits tend to be anonymous. So often, ghost stories are generalized and based more on urban legends than actual fact. A woman in black haunts an English manor (maybe she was a nun, or maybe a widow). The spirit of a murdered person haunts a certain house (Murdered how? When? Who was it? Are there really no crime reports or other records to back this up?) Or the opposite situation occurs: instead of too few details, too many conflicting details exist about a ghost's origins.

A prime example is the Lady in Blue, a spirit haunting the Moss Beach Distillery in Half-Moon Bay, CA. “Unsolved Mysteries” once did a feature on the ghost, presenting three totally different potential backstories and three totally different identities. Was the lady an unnamed flapper stabbed outside a speakeasy by a jealous lover? Was she Alma Reed, the paramour of a well-known composer, who drowned herself in the bay because they couldn’t be together? Or was she Mary Ellen Morley, a young mother killed in a car accident near the present location of the distillery? Some evidence supports the life and death of a woman named Mary Ellen Morley, so because her name is on an obituary and a gravestone, her name is most often attributed to the ghost, even though she may not be the true Lady in Blue.

Here is the episode for your own enjoyment: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ls_Qc...

I encountered a similar situation when I visited the Seelbach Hotel in Louisville, KY last year. One story says the resident Blue Lady is the ghost of a disconsolate wife who threw herself down an elevator shaft when she learned her estranged husband had been killed in an accident while on his way to reconcile with her. Another story claims the ghost was a newlywed bride who killed herself when she discovered her new husband’s infidelity. Who is the real Blue Lady?

(Notice how many ghosts are nameless women reduced to the color of their attire? A departure from form is the Gray Man of Pawley’s Island, SC.)

Even ghosts that have an identity may not have facts on their side. In the excellent Ghostland: An American History in Haunted Places, Colin Dickey debunks several cherished ghost stories. The Myrtles Plantation in South Carolina is said to be haunted by the spirit of Chloe, a slave woman who was mutilated by her master for eavesdropping; as revenge, Chloe poisoned her master's children. Dickey researched the records of Myrtles Plantation and found no slave named Chloe had ever lived there. Furthermore, the children who were supposedly poisoned actually died of fever in another city. So the legend appears to be a bust. But just because the Myrtles isn't haunted by a slave named Chloe doesn't mean it isn't haunted by a ghost at all. Something spectral may very well be happening in South Carolina, and witnesses invented a legend to account for what they experienced.

Dickey doesn't merely bust ghostly backstories; he probes the reasons why society needs ghosts and why it needs its ghosts to adhere to certain norms. Where do these ghostly legends come from, especially if there's no historical foundation for them? What cultural or psychological functions do such tales serve? I had already begun writing Smithy with the intent of exploring the factors involved in the evolution of a ghost story when Ghostland debuted. I thought it offered some wonderful insights.

Smithy is not merely a ghost story, it's also my phenomenological study of ghosts. What are ghosts? How would you identify a ghost? Why do we tell their stories, and why do we tell the particular stories that we do? How would people (e.g., square academics) respond to the possibility of a ghost in their lives?

The best fictional example of a ghost, in my opinion, is “The Empty House” by Algernon Blackwood. It's not a dramatic, Hollywood-ready ghost story. In fact, nothing much happens in it. A pair of amateur investigators visit the titular untenanted domicile on the anniversary of a murder. They experience strange noises and doors slamming as the events of the past are reenacted. No ghosts materialize or interact with our heroes, but by the time they leave the house, they are badly shaken all the same by the eerieness of what they've witnessed. What makes that story memorable is that it plays out the way I imagine a real haunting would. The stories Cohen wrote about weren't like Poltergeist or The Conjuring (even though the latter is supposed to be based on a true story). Real ghosts are more subtle. Real ghosts are just strange enough to make you uneasy, yet insubstantial enough to make you doubt your sanity.

I hope that Smithy reflects the realism of a haunting and all the possibilities it entails

June 12, 2021

Book Signing - July 17 @ 3:00

If you'll be in the Southern California area on Saturday July 17th, please join me at Dark Delicacies in Burbank: https://www.darkdel.com/store/p2401/S...

June 7, 2021

RIP, Cobby

The oldest captive chimp in the US has died: https://www.msn.com/en-us/news/us/our...

June 3, 2021

The Ape

Bibliography

Project Nim

Nim Chimpsky: The Chimp Who Would be Human – Elizabeth Hess

Nim: A Chimpanzee Who Learned Sign Language - Herbert S. Terrace

Unlocking the Cage

The Ape Who Went to College

People of the Forest

Next of Kin: My Conversations with Chimpanzees – Roger Fouts

In preparation for writing Smithy, I investigated various books and documentaries about primates. The primary inspiration behind Smithy was the story of Nim Chimpsky, a chimpanzee who, in the 1970s became the focus of a Columbia University study into primate language. The study (and the name of its subject) developed as a response to then-current theories in cognitive studies that emphasized the uniqueness of the human brain relative to the brains of other animals and the specialization of different areas within that brain. Many scientists believed that only human brains were equipped for language and that it would be impossible for any other species to develop higher forms of communication (above and beyond signals to denote the presence of food or predators, for example). Philosopher Noam Chomsky was particularly vocal about the inability of non-humans to master language. Nim Chimpsky not only parodied Chomsky’s name but attempted to challenge Chomsky’s hypothesis.

Project Nim was developed by Dr. Herbert Terrace (after whom Belancourt Mansion in the novel is named). Initially, Nim was raised in the home of one of Terrace’s former students alongside her own children and step-children. When he was 3 years old, he was moved back to campus and taught sign language in laboratories on-site, but Terrace worried such a scenario was too limited and not engaging enough for his unusual student. In an effort to better simulate the way children learn language within a family, Nim was moved off-campus to a residence, a mansion called Delafield that had been left to the university by an alumnus. Students from across the Eastern seaboard were recruited to live at Delafield, care for Nim, and teach him to sign. Nim wore clothes and was taught to groom himself and perform chores just like a human child. (This didn’t serve any academic purpose in the experiment, but it encouraged the student researchers to think of Nim as a child and interact with him more naturally). Many of Nim’s sessions were filmed and later reviewed by independent judges who evaluated the sharpness of his signs and the content of the messages he transmitted.

Project Nim ran from 1976 to 1977. At that time Nim, was slightly older than Smithy in my story. Although some of Smithy's behaviors would be more appropriate to an older chimp, I chose to accelerate his development for purposes of the storytelling.

Smithy’s story may follow the same trajectory as Nim’s, but Smithy and the other characters in the book are not based on any specific persons from the study. For example, Dr. Preis-Herald combines characteristics of many different public figures, including Dr. Terrace, British ghost hunter Harry Price, and social psychologist Philip Zimbardo.

When the Columbia study concluded, Nim was sent to the Institute for Primate Studies in Norman, Oklahoma. For years, he was studied by psychology students under the supervision of psychologist Bill Lemmon, a domineering and aggressive man whose antics partially inspired the character of Manfred Teague in the continuation of Smithy’s story. Lemmon freely distributed chimpanzees to students, entertainers, or middle-class couples who wanted them, encouraging them to raise the animals in their homes as surrogate children. One associate even incorporated his chimp into therapy sessions with his own patients. Looking back from the 21st Century, it seems outrageous that such delicate, unpredictable, and endangered creatures were loosed wily-nilly into the hands of unqualified caregivers, but it really happened.

Besides Nim, the facility also housed the signing chimps Washoe, Onan, and Ally, who were taught and championed by Dr. Roger Fouts. The fictitious rivalry between Piers Preis-Herald and Robert La Fontaine in my novel is based on the real-life academic disputes between Herbert Terrace and Roger Fouts.

Eventually, the facility closed, in part because Lemmon had fallen on financial difficulties, and in part because primate language studies had fallen out of favor. Sadly, most of the apes—including Nim and Ally—were sold off to medical facilities for testing pharmaceuticals prior to their application on human subjects. The horrific conditions within such facilities, particularly among primates drafted into AIDS research, are widely documented and were scarier than any horror story I could have written.

Why were such remarkable beings thrown away so carelessly? In part, because humans have traditionally held other species in low regard, and in part because the ability of non-human primates to communicate had become doubtful. Terrace repudiated his earlier findings from Project Nim, declaring that Nim (and by extension all other signing primates) didn’t actually use language but instead responded to cues from handlers, much as the infamous horse Clever Hans, who allegedly solved math problems, had relied on the tics of the crowd to know when to stop tapping his hoof. According to Terrace, gullible language researchers, wanting to believe, claimed victories that didn’t really exist.

Among Terrace’s criticisms were Nim’s inability to adhere to rules of syntax (a failing that also applies to certain politicians in high office) and the ambiguity of Nim’s messages. Different judges read different meanings into Nim’s signs. Some of them assumed the implied presence of words that Nim didn’t actually sign. Some of them perceived a string of words to indicate a unified message (i.e., “metal cup drink” = “thermos”) while others perceived that the words existed independently (the object is metal, it is a cup, and it is used to drink). This was an especially detrimental attack because the generativity of language is a characteristic traditionally reserved exclusively for humans; the ability of primates to create new words and phrases from existing words they already knew (e.g., Koko the gorilla, not knowing the sign for wedding ring, called it a “finger bracelet”) was viewed as proof of true language usage.

The trouble is that language is inherently ambiguous, no matter if a human or a chimp is using it. Messages are shaped by context and by the identities and relationships of the parties engaged in communication. As an example, Tatu, one of Roger Fouts’s chimp subjects, loved the color black. She used “black” to describe anything that was interesting or cool. If she liked your neon pink dress, she would tell you your dress was “black.” That statement would be factually incorrect to a disinterested observer, but it makes perfect sense within Tatu’s worldview. How many human children use personal pet terms for different objects?

Another surprising point that emerged from my research was the way different researchers selectively communicated about their findings.

In Nim, his own book about the study, Terrace explains that the project terminated because it was becoming more difficult to find volunteers who would remain in the study long-term, thereby providing more stability for Nim. Also, Nim was growing older, larger, and less tractable. Those reasons were true but they weren’t the whole truth. A romantic falling-out between the primary researchers and injuries repeatedly inflicted on some the students expedited the project’s end. Elizabeth Hess’s book Nim Chimpsky: The Chimp Who Would Be Human and the film adaptation Project Nim are more candid about the downfall of the study, but Terrace’s version of events sounds more professional.

Likewise, controversy surrounds the death of Sequoyah, the baby born to signing chimps Washoe and Ally. Fouts writes in Next of Kin that Sequoyah was injured, the wound became infected, and the baby died. What he doesn’t say is that the injury may have been inflicted by Washoe herself. Again, Hess tells a more complex story. For various reasons, some imposed on her, Washoe struggled with motherhood. Once, she jammed a toothbrush down her infant’s throat instead of using it to clean his teeth as she had been taught. Was that a careless act? Was it a deliberate attempt to punish the source of her frustration? Fouts certainly doesn’t offer any hint.

Fouts also shares his own criticisms of Project Nim in Next of Kin. His chief complaint is that Nim’s language skills were inferior to Washoe’s because Nim was taught in an artificial laboratory setting, through demonstration and rote repetition. Washoe, on the other hand, was taught more organically. Thus, criticisms of Nim’s language abilities may be valid, but those criticisms wouldn’t apply to Washoe. Yes, Nim was taught via rote repetition in a lab, but that wasn’t the entirety of his learning experience, and to claim it was is disingenuous. Nim spent years living with and learning from his teachers in a more “natural” setting. Fouts worked with Nim in Oklahoma. I would be extremely surprised if he were unaware of that aspect of Nim’s background.

Why did Terrace omit contributing factors that cut short Project Nim? Why did Fouts omit significant details about both Nim and Washoe? Why does anybody choose to say certain things and not say other things? Again, messages are shaped by context and by the identities and relationships of the parties engaged in communication.

Smithy represents my attempt to capture the ambiguity of primate communications, the ambiguity of selective reporting, and the ambiguity of ghost stories.

May 22, 2021

The Making of Smithy

Somewhere in my storage unit are my notes from Dr. Des Lauriers’s physical anthropology class sixteen years ago; scribbled in the margins is the phrase, “Leonora Piper = Kanzi.” Perhaps even then I was connecting primate language with the psychic world. Still, it was another ten years before I began to write my first published novel, Smithy, which would blend elements of both.

Back then, I was struck by a common criticism of primates using language. Many times, researchers fail to obtain consistent results with their non-human subjects (much as different paranormal researchers may not be able to obtain the same number of hits from their sensitives every time). The results are open to varying interpretations. Some critics suggest that researchers see what they want to see and allow themselves to be manipulated by their subjects.

Where psychic research was concerned, Piper was considered to be a highly gifted psychic (so good, that British researchers even hatched a test: to have her steal the crown jewels using telekinesis) until she began to commit flagrant fraud. Though Piper claimed she was having a bad day and simply didn’t want to disappoint her expectant testers, the documented instances of chicanery threw all her prior accomplishments into doubt.

Where primate research was concerned, many of the messages from ape subjects—such as Koko, Nim Chimpsky, and Kanzi—communicated through hand signs or lexigram symbols, are vague and elliptical, generating different translations from different human investigators. Not only do the content of primates’ messages come under fire; skeptics also suggest that the apes are not actually communicating at all, they’re just responding to cues from the humans, delivering the responses they’ve been conditioned to understand will result in a reward.

Smithy is a story about a chimpanzee who may or may not be able to communicate using American Sign Language. The question of whether he can or can’t turns on the meaning of the messages he produces, messages that make no sense unless the researchers examining Smithy are willing to consider a wild possibility.

Smithy is able to communicate—with a ghost!

This premise occurred to me through lucky happenstance. While searching the local library for a DVD to watch one night, I ran across the documentary Project Nim about Nim Chimpsky, the subject of an early primate language study. I remembered studying Nim in my college anthropology class, and I was interested in his story. The documentary unfolded a fascinating, often painful, history of an idealistic study and an animal exploited by humans. Students from Columbia University moved with the chimp into a mansion called Delafield that the university provided gratis for their use. There, they raised Nim as if he were a child, dressing him in clothes and teaching him to do chores and perform basic hygiene, and also teaching him sign language.

At the same time, I was reading A Natural History of Ghosts by Roger Clarke. I had been fascinated by the paranormal when I was young and frequently read “true ghost story” books, but this was the first one I had picked up in about 10-15 years. It touched on a number of familiar stories, but provided information I hadn’t known before. For instance, I had read many discussions of the haunting of Borley Rectory, said to be the most haunted house in England and investigated in the 1930s by flamboyant ghost hunter Harry Price. However, what I didn’t know was that Price recruited members of the idle rich to help him investigate the house. His assistants had to be independently wealthy because he made them pay their own room and board.

I read this information about Price and Borley Rectory the day after I had watched the documentary, and I thought, “What a cheapskate! The volunteers in Project Nim got to stay in their house for free.”

Boom! In comparing the investigation of the chimp to the investigation of the haunted house, I inadvertently linked them. I began to think about what would have happened if Nim Chimpsky had been raised and taught at Borley Rectory instead of Delafield. After all, if the student researchers hadn’t had university housing available, they would have had to find their own place—and they might have ended up in a place like Borley Rectory: large, empty, and highly affordable to rent. Most houses are so affordable for a specific reason.

How might the phenomena recorded at Borley Rectory—mysterious fires, flying bricks, messages scrawled on the walls—have been blamed on a chimpanzee, which animals are notorious for being able to get out of “secure” enclosures and for getting into mischief, instead of attributed to a ghost? Moreover, what would the language researchers have thought if their chimp had suddenly started signing as if in conversation with someone when no one else was in the room? Or what if he signed about another person being in the room when no one else was visible? Would they assume that he was only making signs at random and their experiment was a bust? Would they believe the chimp could see and talk to another presence invisible to the human eye? After all, animals are supposed to be able to see ghosts even when people can’t.

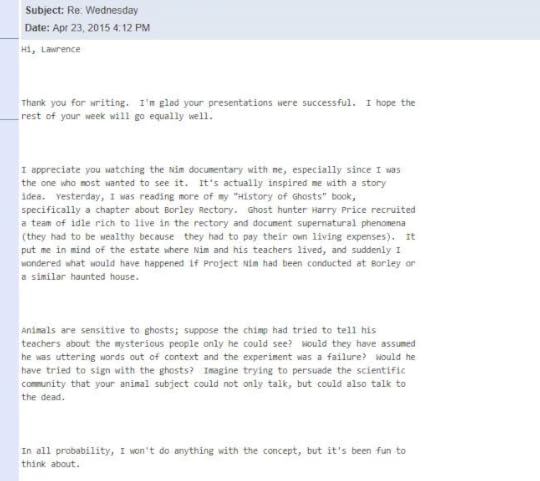

In keeping with the epistolary format of Smithy, here is the e-mail in which I first discussed my idea for the novel with a friend, almost six years to the day before, Smithy was finally published:

I kept thinking about the scenario of the chimp in a haunted house, but it seemed more like a joke than a viable plot. Several months went by before I finally decided to try writing the story. Initially, I considered writing a screenplay, a faux documentary in the style of The Atticus Institute, to mimic Project Nim, the film that had inspired me. I wanted my story to feel believable despite being so far-fetched. In order to make it seem like something that could really happen, I wanted to treat it as something that had really happened. Although parts of Smithy were written in screenplay format (in fact, I wrote chunks of it in a screenwriting class that I was taking through the community college), I ultimately decided that prose would be the best way to explore he scenario and get into my (human) characters’ heads. But I still wanted to maintain a sense of verisimilitude. The best way to do that, I thought, was by making Smithy an epistolary novel, like Dracula or Carrie, and telling the story through letters, diaries, journal articles, news reports, and transcripts.

I still had a big problem though. My concept for Smithy was largely based on details of famous British hauntings, specifically Borley Rectory. However, I had never been to England. I didn’t think I could credibly fake an English setting no matter how many books I might read about life in the countryside or in a manor house. I was already set on the idea that the purported ghost might have been a servant in the big house during its heyday.

Fortunately, I have been to New England before. Every year, for the past 11 years (except 2020—hiss!), I have visited Newport, Rhode Island. Newport is renowned for its mansions. Those mansions would have had servants. I thought I could write about people living in Newport, RI and working with a chimpanzee in a haunted mansion. After all, when I stay in Newport, it’s in a purportedly haunted mansion.

Over the next few weeks, I plan to share more details about the influences that have shaped this novel. I hope that you will find them as fascinating as I did. Perhaps they will inspire you too.