Amanda Desiree's Blog, page 3

February 1, 2024

Smithy Returns in 2024!

April of 2021 saw the publication of my novel Smithy, the story of a chimpanzee raised in a storied Newport, RI mansion who just might have the ability to use language--and who just might be using it to communicate with a spirit lurking in the house.

Smithy's journey didn't end when that book ended. When I initially prepared the manuscript of Smithy's story, it was much longer, covering a twenty-year trajectory. That final draft was so long that I ended up splitting it in half. Part I became Smithy. Now, Inkshares will be releasing Part II of Smithy's remarkable adventure this February in a book called Webster.

The forthcoming book follows Smithy as he departs Trevor Hall and travels across the country to a research lab in California. Ruby and Jeff hope this new environment will give Smithy a fresh start and an opportunity to further develop his sign language skills. Instead, they are dismayed to discover the director of the Center for the Scientific Advancement of Man is an abusive bully who neglects the welfare of the animals and tyrannizes his employees. Worse, accidents in the lab and unruly behavior from the research apes suggest that a phantom presence is still hovering over Smithy. Has the "Dark Woman" followed him from Trevor Hall, or are new entities converging on him?

As word spreads of the weird events at CSAM and Smithy's unusual abilities, his notoriety grows to worldwide proportions, eventually claiming headlines, a place in the court of public opinion, and participation in the court of law. It's a story about belief in the mysterious and faith in the unseen. I think it will thrill you. It may amaze you. It might even . . .terrify you.

I hope you will join me and Smithy for the conclusion of a saga that is out of this world.

January 28, 2024

Amanda Desiree Returns to "Terror at Collinwood"

I recently had another opportunity to appear on Penny Dreadful's Dark Shadows-themed podcast Terror at Collinwood, this time with fellow guest Steve Shutt. We discussed the novel The Dreamers by Roger Manvell, which served as the inspiration for the Dream Curse storyline, and the similarities and differences between the book and the TV presentation.

Additionally, I briefly revisited research I presented at the 2018 Ann Radcliffe Conference in Providence, RI about "contagious" curse-related stories and movies, of which The Dreamers and the Dream Curse are certainly examples.

I had a blast filming the podcast, and I hope you'll enjoy watching it.

January 27, 2024

In the Shadow of the Skull - Now in Paperback!

In the Shadow of the Skull is now available to purchase in paperback from your local book retailer or from amazon.com or barnesandnoble.com

Below are images of the front and back covers.

December 12, 2023

In the Shadow of the Skull: Influences

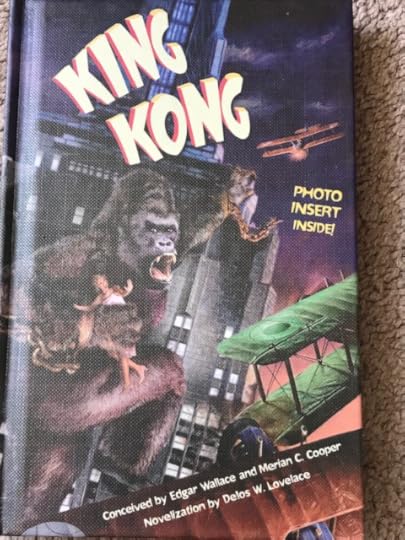

Ninety years after the release of the iconic film, King Kong, I am releasing my own adaptation of the source material, filling in the gaps left in the original story and focusing on the characters and the setting of which we only catch fleeting glimpses on the big screen.

In the Shadow of the Skull has been a work in progress for over ten years. Several years passed after inspiration first struck before I finally began writing it during a period of unemployment in the Great Recession. Suddenly I had time on my hands and decided I should do something productive with it. Besides, King Kong was a story about the dark consequences of greed, a story from another period of economic depression. What better time to tackle a different approach to that story?

Within days of beginning my research for the book, I had the good fortune to find a copy of the text of the 1932 novelization of King Kong at a used book sale. I was able to read the original story from which the 1933 film and all other films that came after it were derived. I used this work as the foundation text for my story.

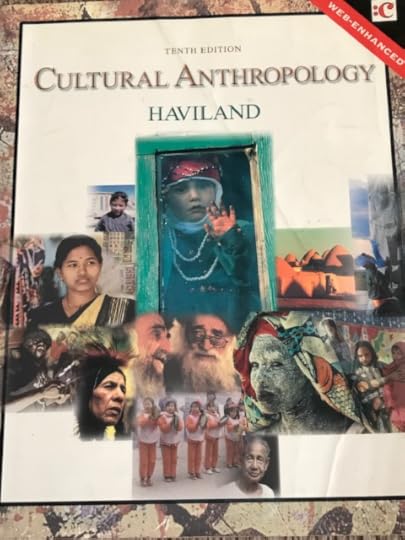

At the time questions about Skull Island, its people, and the young woman who became the original Bride of Kong first began swirling in my mind, I was attending college and taking classes to fulfill requirements for a minor in anthropology. The courses I most enjoyed dealt with cultural anthropology. There, I learned about different societies around the world and their basic aspects: family life and structure, initiation rites, religion, economics.

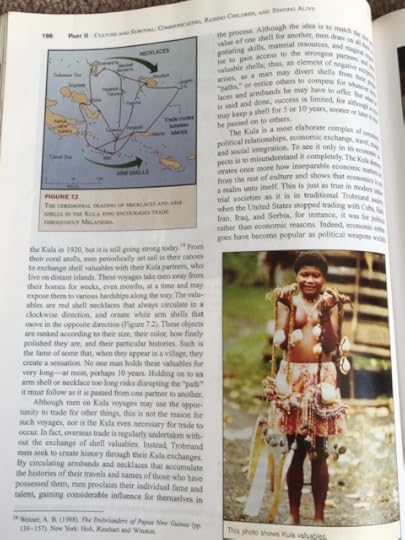

We studied some fascinating cultures from the Pacific Islands, including the people of the Trobriand Islands in Papua New Guinea, who formed a complex trading network and traveled long distances between islands in order to exchange for prestige luxuries, like shells (or maybe gold). The Trobriand Islands are a matrilineal society. Property ownership and family allegiances are traced through female relatives. Consequently, the most significant male figure in one's life is not one's father but one's mother's brother. I thought that was a very intersting shift from Western family structures, one that offered narrative possibilities. Several features of my island's culture and economy derive from the Trobriand Islands.

Living on an island is challenging. Resources are limited. The island soil may not be conducive to agriculture, so food might be hard to grow or find. Medicines could also be hard to obtain. A relatively simple injury like breaking an arm, or even contracting a basic respiratory virus, could be disastrous.

In my Emotions and Motivation seminar in psychology, we learned about the Ifaluk of Micronesia, who live in one such fraught environment. Being constantly on the edge of survival means that everyone has to cooperate in order to endure. Violence and aggression are strongly discouraged. Even divisive emotions like envy or anger could pose a threat. Hence, the Ifaluk have developed an elaborate system of emotions and social mores unlike any other in the world to keep their society functioning smoothly.

Fago is an emotion that can't be exactly translated into English; it incorporates shades of compassion, sympathy, love, pity, and respect. People fago one another in an emergency. If your neighbor is sick, perhaps you show fago by tending to her and bringing her food or other supplies she needs. Fago also manifests in day-to-day interactions. The Ifaluk observe a status hierarchy and pay the proper degree of respect to each person they meet so as not to offend them. The community tries hard to discourage rus, a disruptive emotion ranging from anxiety to panic that could cause a distraction or result in injury. Above all, the Ifaluk try to avoid song (resentment or anger). The elaborate steps necessary to maintain interpersonal connections are staggering.

I referred to the Ifaluk as the primary model for my fictional society. People living in a world filled with dangers and hardships, like Skull Island, would have to carefully regulate their emotions in order to reduce unnecessary conflicts. Anyone who defied social norms or displayed negative emotions could be viewed as a threat. Suppose you were to add giant monsters into such an already-precarious environment?

Trading partner cultures often adopt one another's customs, languages, and beliefs. Though the islanders in my story are fictitious, their world is a melange of actual island societies with which they might have traded or intermarried, woven together into an original fabrication.

When naming my characters, I initially used traditional names from the Indonesian and Micronesian regions. However, members of a writers' critique group to which I submitted early drafts of the book reported difficulty keeping track of all the characters because their names were unusual and unfamiliar. Consequently, in many cases, I trimmed down polysyllabic names (e.g., "Ilefagomar" became "Ilfemar") or adapted names to sound more Anglicized (e.g. Lani, Kori) so they might be easier to remember. Though this was done for expedience, it was not intended to be disrespectful to the cultures that inspired my story.

I hope you will seek out some of the ethnographic works about the Ifaluk and the Trobriand Islanders to learn more about the amazing people who inspired In the Shadow of the Skull.

In the Shadow of the Skull will be available in eBook form this Friday.

December 6, 2023

In the Shadow of the Skull: Origins

People frequently want to know where an author gets their ideas. My own inspiration tends to come from things I read about or see in films and TV shows. Either I imagine myself in the scenario and think about how I would react, or I wonder, "What if this. . ?" "What about that. . ?"

Every year around Halloween, I marathon my favorite films, some of which I've watched for 20 years in a row or more. After so many viewings, my focus sometimes wanders from the plot. During one of my multiple viewings of King Kong years ago, my attention drifted to the frightened young woman being adorned with flowers at the foot of the massive gates in the moments just before Carl Denham and his crew are spotted: The Bride of Kong. I wondered who this person was. I imagined she must have been someone important in the community to be chosen for such an honor. Perhaps she was related to an important figure. More likely, she was the most beautiful girl in the village and therefore the most desirable bride. She had probably led a charmed life up to this point and anticipated a marvelous future and her pick of suitors. But her charms backfired on her when she was chosen to be sacrificed. What must this young bride have been thinking as she sat at the verge of death? What would have crossed her mind when Ann Darrow showed up? She probably thought her luck had changed again. She must have thought she was safe and free to live that wonderful life she'd hoped for after all.

Except she wasn't.

Even though she was no longer the Bride of Kong, even though she survived the ceremony, her world collapsed. Her village was destroyed in Kong's rampage; her people were trampled under his feet or crushed between his powerful teeth.

To a small population, even a handful of deaths can be devastating. If the dead are the young and virile men who are supposed to protect and provide for the community, the devastation is compounded.

Further, Kong destroyed the wall holding back the bloodthirsty monsters in the jungle, so after his initial attack on the village, the dinosaurs, giant spiders, and other beasts would be free to wander over whenever they wanted and pick off any remaining survivors. What a nightmare!

King Kong has been adapted into multiple films, and in no version have I seen any treatment of what happened to the islanders after Kong was taken away. Jeff Bridges's Jack makes a passing remark in the 1976 King Kong that in a year's time, the islanders will become "burnt-out drunks" because the wonder of Kong has been taken from their lives. Still, we don't actually see the suffering of the devastated people. We don't witness them grieving over their lost family and friends, or their lost God. What about the collapse of their way of life? What about the destabilization of their world view caused by seeing their all-powerful God-King hauled away in chains by some strange newcomers? That's the stuff of which postapocalyptic fiction is made.

And what about before the apocalypse? Just who were the people of Skull Island? How did they manage to live side-by-side with monsters? How did they serve Kong, and what did he mean to them? How did they survive from day to day on their remote island? The movies don't tell us.

Even Skull Island's position is nebulous. We're only told that it's "way West of Indonesia," placing it somewhere in the Indian Ocean. The 1933 film cast African-Americans as the islanders, but the costumes and set designs are more typical of the South Pacific than of Africa. What sort of society is this? What history does it have? What legends does it tell?

I decided I might like to address those questions and tell the story of Skull Island and the Bride of Kong--someday.

Years later, my version of that story is now my newest novel, In the Shadow of the Skull, and "someday" is December 15th, when the ebook goes on sale.

December 1, 2023

NaNoWriMo Interview with Amanda Desiree

NaNoWriMo 2023 may be over, but you can still prepare for next November, or for a writing project at any time of the year, by reviewing Inkshares' NaNoWriMo author interview series on Substack.

Here you can read about some of my writing strategies and insights into using different points of view:

June 5, 2023

Guest Appearance on "Terror at Collinwood" Podcast

Recently I was given the opportunity to help spread some terror at Collinwood with horror hostess Penny Dreadful (aka Danielle Gelehrter) on her podcast, appropriately titled "Terror at Collinwood," which celebrates all things related to the TV series "Dark Shadows." I joined author Katherine Kerestman in a discussion of the penultimate story line set in 1840.

This podcast gave me the chance to return to my roots. "Dark Shadows" has been a favorite show for many years. During the 2000s, I faithfully attended the annual Festivals and participated in fan discussions online. "Dark Shadows" gave me the chance to practice my creativity through writing skits, stories, and song parodies.

It was an honor to speak with Penny and Katherine about this elaborate and eventful period in the series.

Video of the conversation can be viewed here:

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=2y_9ba8ORaM

You can download this and other episodes from the podcast and subscribe to it here:

April 7, 2022

What is an Epistolary Novel, and Why Would Anybody Want to Write One?

Have you ever read an epistolary novel? First of all, what is an epistolary novel?

The term "epistolary novel" refers to novels that take the form of written documents, most likely letters. If you know the Bible, perhaps you're familiar with the Epistle of Paul to the Romans, or the Epistle of Paul to the Colossians, or to the Ephesians, and so on. "Epistle" is a synonym for letter.

This style of writing was much more popular prior to the 20th century, back when more people tended to write letters. Some novels are written entirely in an epistolary style (e.g., Dracula, The Moonstone, Pamela) while others use excerpts of letters or diaries (e.g., the works of Jane Austen, The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde). Epistolary texts can be used to advance the plot, such as when a letter that has traveled for weeks over land finally shows up at the last minute to change the outcome of events, or when a hidden diary is discovered that provides back story.

Why might someone choose to write entirely in an epistolary style? One reason is because it creates a sense of realism. Bram Stoker's novel Dracula is entirely epistolary, taking the form of diaries, letters, and newspaper articles, because Stoker wanted to create the sensation that this story had really happened and had been documented in various places by multiple persons. The author's original preface to the book (appearing in Powers of Darkness) is written as if he really discovered this material or acquired it from acquaintances whose identities he's decided to obscure. House of Leaves by Mark Z. Danielewski follows a similar path. This novel takes the form of a dossier, complete with a series of footnotes purportedly written by the person reading it that tell a parallel story. Such realism makes these books scarier.

The epistolary technique also gives readers a chance to get to know different characters more intimately. Elizabeth Hand's novel Wylding Hall is written as an oral history about mysterious events that occurred during the recording of an album in the 1970s. Each band member tells his or her account of what happened in his or her own words. Each piece of the puzzle is presented in a different voice and assembled to form a picture that the reader must interpret. Consequently, a novel told from the point of view of multiple narrators begs the question of which narrators are reliable. Does having many perspectives compensate for the narrator who may be lying, self-serving, or forgetful? Or does it complicate to deciding whom to trust?

Even when there is no question about the narrator's unreliability, an author may choose to prioritize that distorted worldview to enhance the horror of what is happening (e.g., various works by Poe, Guy de Maupassant's "The Horla," Robert W. Chambers's "The Repairer of Reputations.")

Sharing the experience of a minor character can be very entertaining when the character's voice is particularly vibrant. Lucilla Clack in Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone and Cousin Ernest Roger Halbard Melton in Bram Stoker's The Lady of the Shroud are officious bystanders in the main story, but when they cast their two cents in their own words, they are hilarious.

The epistolary style can also make the act of reading more fun and diverse. Instead of perusing one long narrative in the first person or third person, the reader gets to see different formats and different viewpoints, often presented through different fonts (e.g., transcripts versus diaries versus newspaper articles). House of Leaves effects this most dramatically by alternating the appearance of the material the readers experience.

The epistolary format has its drawbacks, too. Some readers dislike having to read atypical fonts or mentally shift gears among characters. Depending on how many characters are in play, it can be challenging to keep straight each person's voice.

Epistolary narratives can also reduce the sense of urgency and drama in the storytelling. Because these documents are produced after the fact, obviously the person who wrote them survived (at least long enough to make the record).

As a reader, I feel frustrated by horror stories that are written as a confessional narrative right up to the bloody end (e.g. various works by Lovecraft, Stephen King's "1922"). Who is going to sit still and write his memoirs while a monster is mere steps away?

I hear its loathsome claws on the floorboards in the hall! It's coming closer and closer. I know it's coming for me. I have mere seconds left. Agghh! Glug, glug, glug.

At least try to make it more realistic:

Something's at the door!

Damn, bullets don't work. Perhaps fire will.

No good. Tell my wife I love her. Agghh! Glug, glug, glug.

Although epistolary novels were more common in the 18th and 19th centuries, they seem to be experiencing a recent resurgence. Both World War Z and Devolution by Max Brooks are epistolary novels (the former an oral history, the latter a dossier of journals and interviews). The aforementioned Wylding Hall and Fantasticland by Mike Bockoven are both oral histories. Piranesi, the latest fantasy by Susanna Clark, is a collection of diaries.

Epistolary works have even expanded to include 21st century media. Things Have Gotten Worse Since We Last Spoke, a novella by Eric LaRocca, is written as a series of chat room logs and private messages. Joe Hill's short story "Twittering From the Circus of the Dead" is indeed a Twitter feed. Most recently, The Candy House by Jennifer Egan includes emails, diaries, and video game narratives.

My 2021 novel Smithy consists of diaries, letters, transcripts and news articles. I chose to utilize this narrative style primarily because I wanted to create a story that felt real (given that much of my story was inspired by actual events). I also wanted to feature different points of view to call into question which character(s) should be trusted and what each character might have to hide. Writing an epistolary novel was often tedious. I played journalist and wrote full-length newsmagazine articles from which I only used excerpts. I kept a calendar with me at all times to keep track of when letters might be exchanged and how often diaries should be written (and when I cut or rearranged scenes, I had to go back and change the timing of all the surrounding entries). My editor tried to discourage me from issuing Smithy as a full epistolary novel. He encouraged me to re-write it as a traditional narrative that occasionally used epistolary sequences. I declined to do that. Not only did I not want to have to re-do three years' worth of work, but I had chosen the epistolary format for good reasons. Perhaps he was right; some reviews have claimed the characters and events feel distant, filtered through writings instead of experienced in the moment. At the end of the day, I'm satisfied with what I produced, and when I find a review that remarks on how realistic the story seems, I feel victorious.

While it may not be an author's principal choice for what to write, the epistolary novel isn't going anywhere soon. An author might decide to write an epistolary novel for myriad reasons, but why might somebody choose to read one? Because it's a challenging, entertaining, unique, and rewarding experience. Now that you have a list of recommendations, try reading one for yourself and see what you think.

March 8, 2022

"Becoming Jane" in Los Angeles

If you are in the LA area, you have the opportunity to explore the exhibit "Becoming Jane: The Evolution of Dr. Jane Goodall," which runs at the Natural History Museum in Exposition Park through April 17, 2022.

The interactive exhibit includes books and toys (including her favorite stuffed toy, a chimpanzee called Jubilee) that influenced young Jane toward wanting to study animals, original notes and sketches from her observations in the Gombe, and photographs and film footage of chimpanzees encountered in Tanzania and around the world, including captive animals in entertainment or research facilities.

The film projections of chimpanzees in the wild are very realistic. When one CGI chimp approached the audience, a service dog barked at it.

Note the program from a pivotal November 16, 1986 scientific conference on chimpanzees features several lectures about chimp cognition, including signing. Although Dr. Goodall was not involved in this branch of research, it's fascinating to see interest in the topic continuing past they heyday of the 1970s.

For more information about the "Becoming Jane" exhibit, please visit NHM.ORG/becoming-jane

[image error][image error][image error]February 11, 2022

Do You Let the Facts Get in the Way of a Good Story?

Does it bother you when an author writes something in a story that you know to be factually incorrect? Do historical anachronisms or omissions bug you? Those things definitely irritate me.

On the surface, it seems like the author is lazy and didn't do enough research to get the facts correct. That isn't an entirely fair judgment. Although common wisdom is to "write what you know," authors can't know everything. Yes, it's reasonable to expect some level of due diligence: read a book, watch a documentary, take a class, or talk to someone who has personal knowledge/experience if you're lacking. But authors can't spend all their time exhaustively studying a subject or they'll never get around to actually writing anything. Moreover, there will probably be some detail that the book/video/class/expert doesn't cover, and what then? You, the author, will probably have to extrapolate or even make something up to fill in the knowledge gap.

When writing Smithy, I felt particular angst because I had set the novel during a decade I didn't personally experience and which many people alive today do remember well, In fact, I was more anxious about possibly writing something historically or culturally inaccurate in this book than I am in writing my current Edwardian era novel. As I saw it, if I messed up the seventies, "everybody" would notice.

Granted, I'm still bracing myself for criticisms about my depictions of American Sign Language (in which I'm not fluent) or chimpanzees (which I have only seen through barriers in a zoo), but I figure fewer people in the world are going to be experts in those subjects than in the "Me Decade." I looked up what I could (e.g., movie release dates, current events, even, in one case, the weather in an almanac) and I gave the draft novel to beta readers who were at least teenagers during the time period when Smithy takes place, in the expectation that one of them would tell me if something felt false, Nevertheless, I'm sure I didn't cover every base, I tried my best.

Another common possibility behind factual inaccuracies is that the author is using good ol' dramatic license, consciously choosing to print a lie because it makes a better (i.e., more dramatic, more suspenseful, scarier, or funnier) story. I experienced this while writing Smithy, too.

It had been my intention to include a scene early in the novel where one character has to administer the Heimlich maneuver to another character. This was to be a dramatic event, a sense of threat sobering an the enthusiastic start to a new venture, and a bonding experience of sorts for the characters. However, when I researched the Heimlich maneuver, I discovered that the first published reference to this technique was in a medical journal in June of 1974. Smithy opens in May of 1974.

What to do? Should I go ahead and write the scene as I had planned, even though I knew the Heimlich maneuver effectively didn't exist yet? Should I deliberately violate historical accuracy, something I've always hated seeing other authors do? That's definitely something readers would catch. Should I cut the scene, or delay it until later in the book, even though I thought it was valuable to the story? Ultimately, I decided to shift the scene slightly, to June of 1974. Even though it's still highly unlikely that my character would have yet been aware of the Heimlich maneuver, the timing was a little more appropriate. At any rate, I felt at peace with the compromise.

Suffice it to say that after my own experiences striving to maintain a sense of accuracy and realism in my fiction, I have a little more tolerance for other authors' "mistakes." While I still think it's important to research a subject and make an honest attempt at accuracy, I know it isn't always 100% possible. Now, when I run across something "wrong" in a book, I think twice before condemning the author as lazy or uninformed. I wonder what processes went into the writing, what decisions were made. Much occurs behind the scenes that we may never know.