Bodhipaksa's Blog, page 81

January 18, 2012

Researchers have been able to prod yeast to evolve multicellularity

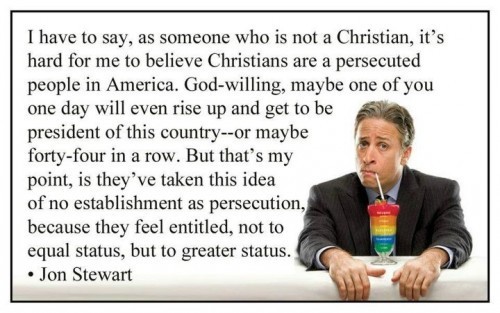

Fascinating. How, starting in the Great Depression, the 1% "bought" Christianity.

January 17, 2012

Word.

January 16, 2012

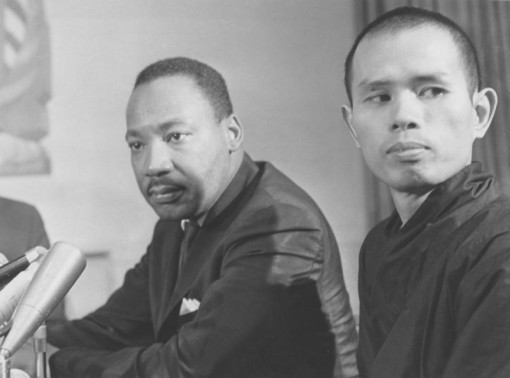

Martin Luther King and Thich Nhat Hanh

On the occasion of Martin Luther King Day, it's worth reading the letter he wrote to the Nobel Peace Prize committee, nominating the Buddhist monk-activist, Thich Hnat Hanh:

1967 25, January

The Nobel Institute

Drammesnsveien 19

Oslo, NORWAY

Gentlemen:

As the Nobel Peace Prize Laureate of 1964, I now have the pleasure of proposing to you the name of Thich Nhat Hanh for that award in 1967. I do not personally know of anyone more worthy of the Nobel Peace Prize than this gentle Buddhist monk from Vietnam.

This would be a notably auspicious year for you to bestow your Prize on the Venerable Nhat Hanh. Here is an apostle of peace and non-violence, cruelly separated from his own people while they are oppressed by a vicious war which has grown to threaten the sanity and security of the entire world.

Because no honor is more respected than the Nobel Peace Prize, conferring the Prize on Nhat Hanh would itself be a most generous act of peace. It would remind all nations that men of good will stand ready to lead warring elements out of an abyss of hatred and destruction. It would re-awaken men to the teaching of beauty and love found in peace. It would help to revive hopes for a new order of justice and harmony.

I know Thich Nhat Hanh, and am privileged to call him my friend. Let me share with you some things I know about him. You will find in this single human being an awesome range of abilities and interests.

He is a holy man, for he is humble and devout. He is a scholar of immense intellectual capacity. The author of ten published volumes, he is also a poet of superb clarity and human compassion. His academic discipline is the Philosophy of Religion, of which he is Professor at Van Hanh, the Buddhist University he helped found in Saigon. He directs the Institute for Social Studies at this University. This amazing man also is editor of Thien My, an influential Buddhist weekly publication. And he is Director of Youth for Social Service, a Vietnamese institution which trains young people for the peaceable rehabilitation of their country.

Thich Nhat Hanh today is virtually homeless and stateless. If he were to return to Vietnam, which he passionately wishes to do, his life would be in great peril. He is the victim of a particularly brutal exile because he proposes to carry his advocacy of peace to his own people. What a tragic commentary this is on the existing situation in Vietnam and those who perpetuate it.

The history of Vietnam is filled with chapters of exploitation by outside powers and corrupted men of wealth, until even now the Vietnamese are harshly ruled, ill-fed, poorly housed, and burdened by all the hardships and terrors of modern warfare.

Thich Nhat Hanh offers a way out of this nightmare, a solution acceptable to rational leaders. He has traveled the world, counseling statesmen, religious leaders, scholars and writers, and enlisting their support. His ideas for peace, if applied, would build a monument to ecumenism, to world brotherhood, to humanity.

I respectfully recommend to you that you invest his cause with the acknowledged grandeur of the Nobel Peace Prize of 1967. Thich Nhat Hanh would bear this honor with grace and humility.

Sincerely,

Martin Luther King, Jr.

January 14, 2012

Five ways to increase your joy

Joy (sukha in Pali) should be our natural state of being. Unfortunately, though, we've been brought up in a society that emphasizes wanting things and having things as the primary path to happiness. Wanting things actually destroys joy, while having things brings only a short-term burst of pleasure that fades quickly.

Joy (sukha in Pali) should be our natural state of being. Unfortunately, though, we've been brought up in a society that emphasizes wanting things and having things as the primary path to happiness. Wanting things actually destroys joy, while having things brings only a short-term burst of pleasure that fades quickly.

In fact, thinking that joy depends on things outside of ourselves is a trap. It makes it harder for us to experience real happiness. True happiness comes from our attitude toward things, not to things themselves.

Despite its seeming elusiveness, it's possible for us to spend much of our time in a state of joy, and here are a few suggestions for moving in that direction:

1. Smile

Remembering to smile has a potent effect on how we feel. It sparks off a whole chain of mental and physical events, and promotes a sense of happiness. We can even smile in the face of pain and fear. This reminds us that basically things are OK, right now. Yes, things are not "perfect," but we can deal with it.

Rick Hanson, the author of The Buddha's Brain, reminds us that the mind has a built-in negativity bias. We're more likely to pay attention to potential threats than to benefits — even benefits that presently exist. As he puts it, the mind "is like Velcro for negative experiences and Teflon for positive ones." Smiling implicitly connects us with the positive.

2. Appreciate

Along the same lines, appreciation supports the arising of joy. This is true both in meditation and in our ordinary lives. When people were asked to write a letter of appreciation to someone who had benefitted them, they were measurably happier for weeks afterward. Explicit appreciation is the most effective. When we say words of thanks to ourselves, even in our own heads, it makes the appreciation more real — probably because it involves more of the brain.

So in meditation I have a practice I sometimes do of saying "thanks" for all the things that are going right. I notice that the climate is livable (even if it doesn't fit my narrow conception of "ideal") and say "thank you." I notice the room around me, appreciate that it's sheltering me from the elements, and say "thank you." I notice that the electricity, gas, internet connection are functioning, and say "thank you" (I'll do these separately, but I'm abbreviating the process here for the sake of brevity). I'll say thank you in this way for:

Living in a country where there's law and order,

The presence of other people around me, some of whom I have loving relationships with,

The presence of furnishings (this is unimaginable luxury for many people in the world),

Individual body parts that function, day in, day out,

Functioning senses,

Functioning utilities — internet, water, electricity, etc.,

A world round about me that's filled with beauty.

This practice can be very detailed. In fact it's best that it's very, very detailed, so where I've said "individual body parts" above, you can in fact do a detailed body scan, identifying each part of the body in turn and saying "thank you" to each. Even where there's pain, you can note that the body part is still struggling to function for you, and trying to heal. (This, incidentally, can free us from the tendency to blame the body for being sick or in pain.)

3. Imbue your experience with a sense of lovingkindness

To be loving is one of our deepest needs. The experience of loving is deeply beneficial to us, and helps bring about a sense of wellbeing and joy.

Jan Chozen Bays, in her book, How to Train a Wild Elephant, writes very beautifully about the practices of "loving gaze" and "loving touch." You can simply evoke the experience of looking with love (for example, remembering looking at a sleeping child) or of touching with love (for example, placing a hand on someone who is in pain). By recalling those ways of interacting, we can bring a sense of love into our experience right now.

As you become aware of your body in meditation, for example, you don't have to do that in a cold and clinical way. You can "gaze" (not literally, but in terms of being aware) inwardly in a loving way, and fill your entire body with a sense of love.

4. Feel loved

It can also be very helpful to feel loved. In one traditional form of the lovingkindness meditation, we begin by recalling someone ("the benefactor") who has shown us kindness. By doing so we can recapture the feeling of being loved, which again is an important support for a sense of "everything being all right."

If it's hard to recapture that feeling, you can imagine being a baby in your mother's arms, warm and loved and cared-for.

Sometimes I've found it useful just to imagine that there's a source of light and love in the world, that I can tap into. I'll imagine that I'm at the receiving end of a shaft of light, and that this light touches me in a loving way, flooding my being with lovingkindness.

I've also sometimes imagined that I'm meditating with the Buddha, not in an idealized and iconic form like you see in Tibetan paintings, but just as an ordinary man sitting beside me. And I'll drop into my mind the phrase "feel the love of the Buddha." What then happens is that I'll feel a sense that the Buddha is radiating love, like an aura, and that I'm on the receiving end of his blessings.

5. Savor the positive

Notice and appreciate any positive experiences that rise, however ordinary they may be. It could be the simple feeling of a coffee cup warming your hands, or seeing the sunlight shining through a window. Or it could be a pleasant feeling that arises when you think of a friend. In meditation, this could be a pleasant sensation of energy in one part of the body, or the simple rhythm of the breath, or a sense that the body is relaxing, or moments of calmness beginning to appear in the mind, or a sense of light, or any spontaneous and pleasing imagery that may appear in the mind

Your attention may want to slide quickly onto something else, but this is just an instance of the mind's tendency to take the positive for granted and to go looking for something to be troubled with. So notice anything positive in your experience.

Don't grasp after such experiences though, and don't cling to them. All experiences pass. In fact experiences are passing as we have them. So let them go, and don't mourn their passing. Just appreciate them as best you can.

January 10, 2012

Introducing "More Than Sound"

We're delighted to announce that through a partnership with More Than Sound, an independent production and publishing company, we now have some excellent new audio digital downloads in our online store.

More Than Sound aims to benefit the world by making available audio programs on Emotional Intelligence, leadership, and meditation and mindfulness, and they have excellent materials presented by world-class authorities, such as Dan Goleman, Daniel Siegel, Naomi Wolf, Richard Davidson, and even George Lucas.

More Than Sound is the brainchild of Hanuman Goleman, who developed and participated in The Wisdom Preservation Project, recording interviews with Buddhist masters in Myanmar, and who started the company after getting his M.A. in Media Arts from Emerson College.

Here are some of the titles we have available:

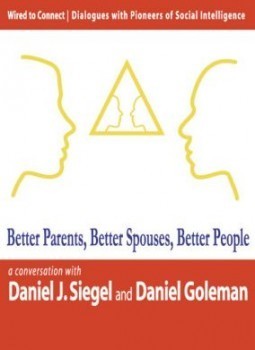

Better Parents, Better Spouses, Better People, Dan Siegel & Daniel Goleman

Daniel J. Siegel and Daniel Goleman explain how we can free ourselves from the hold of our past to create richer, more balanced relationships.

Daniel J. Siegel and Daniel Goleman explain how we can free ourselves from the hold of our past to create richer, more balanced relationships.

Understand how our parents' behavior impacts our mental, neural, and social development.

Learn how self-reflection and awareness transform our relationships with our children, spouses, and selves.

Discover how emotional habits can change at any age.

In this insightful exploration, Siegel and Goleman explain how our relationships shape our emotional habits – and the brain itself. The neural patterns formed in childhood have immense importance in our lives as parents, lovers, and people. Awareness, however, can help rewire the brain and help us create healthier relationships.

Digital Download (56.5 MB)

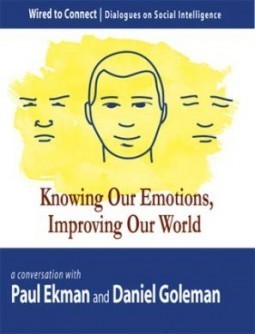

Knowing Our Emotions, Improving Our World, by Daniel Goleman and Paul Ekman

Dan Goleman and Paul Ekman discuss the fascinating science of Social Intelligence, and how we can use it to harness our emotions.

Dan Goleman and Paul Ekman discuss the fascinating science of Social Intelligence, and how we can use it to harness our emotions.

All emotions, including hidden ones, have their own distinct facial marker

With practice we can discern other's truthfulness and intent

We can free ourselves from the grip of regrettable emotional episodes

Research into facial expression and emotion reveals two startling facts: people cannot conceal their emotions, nor can they fabricate genuine emotions. Minute facial movements and gestures reveal true feelings and intent – regardless of efforts to conceal them. Learning the connection between the face and the emotions can better our lives by giving us the ability to recognize our own emotions before they overwhelm our better judgment.

Digital Download (58 MB)

Training the Brain: Cultivating Emotional Skills, by Daniel Goleman and Richard Davidson

In this accessible dialogue, Dan Goleman and Richard Davidson explain the science behind our emotions.

In this accessible dialogue, Dan Goleman and Richard Davidson explain the science behind our emotions.

Understand the brain systems involved in: self-awareness, motivation, and emotional recovery

How childhood experience directs gene expression and neural development

How the brain can be trained for a happier, less stressful life

Detailing the neurological effects of contemplation, Goleman and Davidson show how we can activate our brains to recover from stress and anxiety, and conquer fear. Goleman and Davidson offer a new vision for emotional education at any age.

Digital Download (55 MB)

To see a full list of More Than Sound titles, visit our online store.

January 3, 2012

"To see what is in front of one's nose needs a constant struggle." George Orwell

Metaphors can be traps. We can end up taking them too literally. The point of a metaphor is to help us see things more clearly ("time slips through our hands like sand" helps us connect something intangible and abstract, like time, to a physical experience, like sand trickling through our fingers). But sometimes metaphors mislead, and make it harder to see things clearly. The image of the path is one of those metaphors that can potentially trap and mislead us.

Metaphors can be traps. We can end up taking them too literally. The point of a metaphor is to help us see things more clearly ("time slips through our hands like sand" helps us connect something intangible and abstract, like time, to a physical experience, like sand trickling through our fingers). But sometimes metaphors mislead, and make it harder to see things clearly. The image of the path is one of those metaphors that can potentially trap and mislead us.

The Buddha himself used the image of his teaching being a path. One of his key teachings is the Eightfold Path (a??ha?gika magga), and in a famous teaching he explained that he was like an explorer who had beaten a path to an ancient city that had been lost in the jungle, and has come back to lead others along the path to see his discovery for themselves. It's a venerable image. The problem isn't the image itself, but how we relate to it.

How long is this path?

The thing that strikes me as a problem with the path metaphor could be expressed in a question: how long do we think the path is?

In the Buddha's day, people would often get enlightened very quickly. In some cases they just had to hear a phrase, and insight would arise. In some cases it would take longer — perhaps some years of practice. But it was doable. Even people living householder lifestyles would get enlightened without too much difficulty. I'm not aware of examples of householders getting enlightened immediately, but there were, according to the scriptures, thousands of lay followers who attained the first level of enlightenment, and many hundreds who were just short of full awakening. The path was short. In the case of those who got enlightened immediately, it wasn't so such a path as a single step.

The later Mah?y?na teachings tended to elevate enlightenment in order to glorify the Buddha's attainment and inspire faith. The bigger his attainment, the greater the spiritual hero we was, right? And the greater a spiritual hero he was, the more inspiring he was? The problem was that they started talking in terms of the path to awakening stretching over an uncountable number of lifetimes. Sure, this was meant to inspire us, but if you believe enlightenment is unattainable in this very lifetime, what's the chance that it's actually going to happen? If you think it's going to take thousands of lifetimes to get enlightened, it's probably not going to happen to you in this life. Not next year. And certainly not right now, in this very moment.

An alternative to the "path" metaphor

So what's the alternative to thinking of enlightenment as being at the end of a long, long path? You could think of it as being at the end of a short path: that's pretty much what the Buddha seemed to have in mind. Or you use a different metaphor, and think of awakening as being right here, right now, but you're not seeing it because you're looking at your experience the wrong way. It's like one of those "Magic Eye" 3D pictures from the 1990s that looks like a mess of squiggles and images fragments, until you let your eyes refocus in just the right way, and suddenly there's a stereoscopic image right there in front of you. In a way, the image has been there all along, but you weren't looking in the right way. Maybe at certain points you didn't believe that you could ever see the image. Maybe you started to doubt there was anything there. But if you persist then — boom! — there it is.

Our spiritual cognitive distortions

There are a couple of Buddhist teachings that I think relate to this metaphor of the image that's right in front of us, but unseen. One of these is the "Four Vipall?sas." The word vipall?sa means "inversion, perversion, derangement, corruption, distortion." It's similar to what psychologists nowadays call a "cognitive distortion." These four vipall?sas — or "spiritual cognitive distortions" — are that we see things that are impermanent as being permanent, see things that are sources of pain as being sources of happiness, see things that are lacking in inherent selfhood as having inherent selfhood, and see things that are ugly as being attractive.

Here's the interesting thing: it's not as if impermanence, for example, is hidden from us. We just don't see it. It's right in front of us, all the time, but our minds don't seem to be equipped to notice it. In fact, I've noticed that Buddhists often like to talk about impermanence more than actually observe it.

So it's happening right now. Anything you notice is changing. When you notice your body you may think "Oh, there's my body" but actually all you're noticing is an ever-changing pattern of sensation. There's no "body" there that you can perceive. Right now you're reading these words. What you're seeing is constantly changing. What's in your mind is constantly changing. Everything in your mind is constantly changing. Try looking for something in your experience that doesn't change. Having any luck? You say that the coffee cup in front of you isn't changing? But you don't ever experience a "coffee cup." You have sense impressions of a coffee cup, and those sense impressions are in constant flux. Your eyes are jittering around all the time, because the receptors in your retinas stop responding if they're exposed to the same stimulus for more than a fraction of a second. If your eye was frozen in place you'd literally be blind. The only reason you can perceive anything is because of change — impermanence.

So change, non-self, etc., are there all the time. We just need to pay attention. Look. Look right now. Everything you're experiencing is changing. Keep looking. Eventually, as with the Magic Eye pictures, you'll see what's been there all along.

Not seeing the wood for the trees

I said there were a couple of teachings relating to not seeing what's in front of us. The vipall?sas constitute one such teaching. The third fetter of "s?labbata-par?m?sa," usually translated as "dependence on rites and rituals," is another. This is one of the three fetters that we break when we attain stream-entry, the first level of enlightenment.

The first fetter is straightforward — it's when we no longer believe that we have a permanent, unchanging self. We keep observing that our experience is changing all the time, and eventually it clicks — that's all there is. There's just change.

The second fetter is doubt. Until we experience the breaking of the first fetter, there's always some kind of doubt that it's even possible. We may doubt that we can do it. (Sure, other people can see these Magic Eye pictures, but I can't.) Or we may doubt that there's a picture there. ("It's a trick," we say, as we stare hopelessly and the jumbled image.) Once we've seen that the separate and permanent self we've always taken for granted is an illusion, and once we've realized that it's true that everything in our experience — everything! — is a constant flux, we feel a surge of confidence. We've stepped out of illusion, we know that the Buddha's teaching is right, and we have confidence that further progress is possible. Actually, it's inevitable.

But that third fetter — "dependence on rites and rituals" — what's that got to do with anything? First it's not a very good translation. "S?la" is ethics, and "vata" (the second part of s?labbata) is a religious duty, or observance, or spiritual practice. This is referring to the problem of our getting caught up in spiritual practices so that they become a hindrance to enlightenment, rather than a means to realizing enlightenment.

Enlightenment is right here, right now

One of the most striking aspects of the experience of stream entry is a feeling of immediacy. When we have that perceptual shift and realize that what we've thought of as our "self" (permanent, unchanging, separate) is nothing more than a constellation of constantly changing events, it also strikes us that this is "obvious." It's right in front of our nose. It's been in front of our nose our whole lives. But we just haven't noticed.

Even the spiritual practices (s?la and vata) that we've been engaged with have sometimes prevented us from seeing the truth. We've been talking about impermanence, but not looking at it. We've been studying the path rather than walking it. Sometimes perhaps we've been walking the path, but haven't wanted to stray too far, because it's safe staying with the known.

So I suggest that sometimes, at least, we forget about the metaphor of the path, and instead think of enlightenment as being right here, right now. It's just a question of recognizing what's really going on — of allowing ourselves to see the impermanence that permeates every one of our experiences. We just need to look, and keep looking, until we see the obvious that's sitting right in front of our noses.

"To see what is in front of one's nose needs a constant struggle" is from Orwell's essay "In Front of Your Nose," which was first published in the Tribune newspaper, London, March 22, 1946.

December 12, 2011

How to deal with anger

I don't know if anger, rage, and frustration are getting more common, but it certainly seems like they are.

I don't know if anger, rage, and frustration are getting more common, but it certainly seems like they are.

As we find ourselves snarled in impossibly heavy traffic, overloaded with life's complexities, dealing with technology that we think should work but sometimes doesn't, and struggling to survive in a precarious and heartless economic system, it seems a lot of people live with hot coals of irritability burning inside them, and that these hot coals have more than ample opportunity to burst into the flames of anger, or to erupt as emotional explosions of rage.

Techniques from meditation can help us to damp down the flames of our ill will.

Stop, drop, and love

If you find yourself caught up in resentment and anger toward someone, the simple solution is just to stop whatever you're doing and to start cultivating metta. This definitely works. In my own practice I've lost count of the number of times that I've gone from being irritated with someone to feeling appreciative of them — sometimes in the space of just a few minutes — when I've cultivated lovingkindness toward them. Many times, of course, the ill will is more entrenched, and the best I've been able to do is to soften the anger a little. But even that's progress.

You can do this when you're walking, talking, or driving. Just introduce a current of well-wishing: may you be well, may you be happy, may you be free from suffering.

If anger arises in meditation, just switch over to cultivating metta. Sometimes people think they "shouldn't" stop the practice they're doing, based perhaps on a desire to avoid the restlessness that comes from chopping and changing practices. And while changing practices just because your mind is flighty isn't a good idea, in the case of anger arising, just let go of any notion that you "should" continue with the meditation you've been doing. Anger can be a very destructive emotion, and it's wise to treat is as an emergency situation. So switch to cultivating lovingkindness.

This doesn't necessarily mean doing the full five-stage metta bhavana practice. If you're annoyed with someone, you can just call them to mind and wish them well. You can keep doing this for as long as necessary. You may find that after a few minutes you can return to the practice you were doing, or you may end up working on developing lovingkindness for the rest of the sit.

Adjust your attitude

The way we're looking at the world can set us up for experiences of ill will. For example, when we're expecting perfection, we'll get frustrated, because perfection doesn't exist. Most people who are habitually angry have something like this going on. We often expect perfection from ourselves, from others, and from our technology, which, when you think about it, is both unreasonable and a recipe for misery.

So you can look at your attitudes, and see if you're inadvertently creating the conditions for irritability to arise. It's useful to think in terms of accessing qualities playfulness and humor, which you can do via imagery or a memory of having those qualities.

Accentuate the positive

Also along the lines of how our views condition our emotions, when we're angry with someone we generally focus only on their faults. If you remind yourself of positive things about the person you're angry with, this helps undercut your irritation with them.

It can also be helpful to remind yourself that you have faults as well.

Guard the gates

Exposing ourselves to unpleasant stimuli also sets us up for experiences of ill will. Hanging out in internet forums where there's a lot of negativity, or watching a lot of outraged discussion on television may make you more prone to ill will.

The Buddha called this practice "guarding the gates of the senses." He compared it to posting guards at the gates of a great city. If you want a peaceful city, then keep vagabonds and ruffians out.

This reminds me of the computer programmers' saying, "Garbage In, Garbage Out," which means that if you put in nonsensical data, then your computer will output nonsensical data. In this case, it's our minds that are the computers. We need to be aware of the fact that certain forms of input lead to the output of angry emotions. If you want to reduce the output of anger, then cut back on the input of anger-generating stimuli.

Summon a Super Hero

Superman or Batman won't swoop down to save you from your anger, but calling to mind a patient friend can help you to act with greater forbearance. One of the problems we face is with having a limited menu of behavioral options to choose from. When you're prone to anger, it's because anger is just so damned easy to use as a tool. You're in a frustrating situation, you reach into your behavioral toolbox, and anger leaps into your hand. Thinking of how someone who is patient and kind might act actually enlarges the range of tools open to you, so that you don't fly off the handle. A while back I read about an interesting study where some students were asked to think about a professor before taking an exam. Those students who thought about the professor actually performed better on the quiz!

Practice self-compassion

This last technique is the one I find to be the most powerful of all. When you get angry, you're actually reacting to a sensation of discomfort. There are stages involved in getting angry. First we see, hear, think, or otherwise perceive something. Then our mind categorizes the perception as wrong, bad, threatening, or otherwise unacceptable. This produces an unpleasant feeling, which is often centered in the solar plexus. And that unpleasant feeling acts as a signal, triggering a response of anger. The anger itself is designed to scare away the thing we identify as being the threat to our well-being. This works great if you're a alpha wolf who's facing a rival for pack supremacy. Snarl just the right way and your rival will slink off, chastened. It works less well in intimate family relationships or at work, where anger creates bad feelings and resentment, or when you're frustrated with a slow website, where anger accomplishes nothing useful at all.

The "gut feeling" part of this process is something we often don't pay attention to, although we should. Our anger, frustration, or rage arises so quickly that we're immediately caught up in angry thoughts and emotions, and usually we don't really acknowledge that we're in pain.

But I've found that if I pay attention to the fact that I'm in experiencing discomfort, then the whole superstructure of angry thinking and angry emotions simply collapses. The whole point of anger is to defend you from feelings of pain by removing their source (the angry wolf snarls at its rival, and the rival backs down). But if you mindfully and compassionately pay attention to your discomfort, then there's no need to get angry. The pain is being dealt with creatively.

Having paid attention mindfully and compassionately to my discomfort, I find not only that my anger subsides entirely, but that I often feel compassion to anyone who may have done something I felt annoyed by — like my children clamoring for my attention when I'm busy, or a driver who's cut me off.

As I pay attention to them, the embers of hurt remind me that just as I suffer and want to find happiness, so others suffer and want to find happiness. I find that the slow burn of hurt, while it lasts, becomes fuel for kindness, rather than for anger.

Anger is nothing more than a strategy for finding happiness in the midst of a challenging world, but it's not a very effective strategy. Mindfulness and compassion work much, much better.

Related posts:

Transforming hurt and anger through self-compassion

Defusing the anger bomb

December 9, 2011

Give the teens in your life the gift of calmness

Almost ever summer over the last ten years, I've been teaching low income teens how to use their minds more effectively so that they can be more successful students, but also so that they can be more successful, happier, less stressed individuals.

Almost ever summer over the last ten years, I've been teaching low income teens how to use their minds more effectively so that they can be more successful students, but also so that they can be more successful, happier, less stressed individuals.

We cover a lot of ground in my six-week course, but a core element is the practice of meditation. I was hesitant to do this. I wondered whether these restless teens would be able to sit still even for five to ten minutes. And what if they thought it was lame?

As it turned out, the most common comment in the end-of-term evaluation reports was "The best part was the meditation. I wish we could have done more!"

So this summer I promised my students that I'd make a CD based on the meditations I'd done with them. We'd covered body scanning (focusing on bodily sensations in order to calm the mind), using looking and listening in an open and receptive way as a means to bring about inner peace, meditation on the breath, a little lovingkindness meditation, and even some creative visualization.

I'm pleased to announce that the CD — Mindfulness Meditations for Teens — is now available on Wildmind's online store. This album is also available as an audio download. It's on the way to Amazon, although they're saying it's currently unavailable.

Christmas is coming up. Why not treat the teens in your life to some inner calm? If you get them meditating it'll probably bring a bit more calm into your life, too!

Related posts:

Monks teach meditation to incarcerated teens

A little calmness can go a long way

Relax, kids: Meditation touted as stress buster for children

December 6, 2011

Waking up from the hindrance of sloth and torpor

Have you noticed that half the time when you ask people how they are, they answer with "tired"? We all seem to be tired, and when we sit down to meditate we may find that we nod off or sit there in a rather dreamy and unfocused state.

Have you noticed that half the time when you ask people how they are, they answer with "tired"? We all seem to be tired, and when we sit down to meditate we may find that we nod off or sit there in a rather dreamy and unfocused state.

This is sloth and torpor — one of the states of distraction that we call the Five Hindrances. The schema of the Five Hindrances is a diagnostic tool that, combined with traditional "antidotes," can help us to engage creatively with our experience in order to become more joyful, calm, and focused.

Most of the specific antidotes to the hindrances that I'm learned have been shared by other practitioners, or come from the commentarial tradition, but sloth and torpor is one of the rare hindrances where detailed instructions have been preserved in the original scriptures.

In talking with one of his chief disciples, Moggallana, the Buddha gave a list of suggestions for dealing with tiredness:

"Whatever perception you have in mind when drowsiness descends on you, don't attend to that perception, don't pursue it. It's possible that by doing this you will shake off your drowsiness.

One of the main applications of this is that when you're tired, you shouldn't focus on sensations low in the body. Rather than paying attention to the movements of the abdomen, which will further encourage sleepiness, you should notice sensations that are higher up in the body, like the sensations of the breathing in the upper chest and head.

"But if by doing this you don't shake off your drowsiness, then recall to your awareness the Dhamma as you have heard & memorized it, re-examine it & ponder it over in your mind. It's possible that by doing this you will shake off your drowsiness.

Reflect on the Dhamma — the Buddhist teachings — helps to focus the mind, preventing it from drifting aimlessly. Also, the reminder of a "higher purpose" may have the effect of inspiring us and of arousing our energy and enthusiasm. You can run through a list such as the Four Noble Truths, of the Five Precepts, or the Eightfold Path, and give yourself an inner Dharma talk. You can even imagine that you're explaining the teachings to a friend. A lot of people don't have these lists memorized, which is a shame, and I'd highly recommend the practice of committing these teachings to memory. The effort really pays off in terms of mental clarity.

"But if by doing this you don't shake off your drowsiness, then repeat aloud in detail the Dhamma as you have heard & memorized it. It's possible that by doing this you will shake off your drowsiness.

So, this is the same advice, but here we're talking out loud, which is further going to prevent us from falling asleep. For obvious reasons this method isn't very appropriate when you're meditating with others.

"But if by doing this you don't shake off your drowsiness, then pull both your earlobes and rub your limbs with your hands. It's possible that by doing this you will shake off your drowsiness.

So now we move on to physical stimulation, which gets the blood flowing, and which encourages the release of endorphins. The most useful form of stimulation I've found is yoga stretches — particularly when we stretch the hamstrings or hip muscles.

"But if by doing this you don't shake off your drowsiness, then get up from your seat and, after washing your eyes out with water, look around in all directions and upward to the major stars & constellations. It's possible that by doing this you will shake off your drowsiness.

Water in the face gives us a creative shock to the system.

This suggestion also takes us more in the direction of paying attention to light, which is the next piece of advice we'll hear. Also the suggestion of raising the head to look up is significant. When we're tired, we look down and the chin drops. When this happens, a chain reaction is kicked off: our experience is visually darker, our breathing shifts to the abdomen, and the center of our awareness typically moves downward in the body. All of these things heighten our sense of sleepiness. These effects can be noticeable with even a tiny movement downward of the chin. Raising the chin can cause mental stimulation.

"But if by doing this you don't shake off your drowsiness, then attend to the perception of light, resolve on the perception of daytime, [dwelling] by night as by day, and by day as by night. By means of an awareness thus open & unhampered, develop a brightened mind. It's possible that by doing this you will shake off your drowsiness.

If you have candles on your altar, then you can open your eyes and look at a candle. You can visualize light. You can imagine that you're looking at a bright light. Or, if you relax and just notice your field of awareness, you may notice that some parts of your experience are brighter than others. You can pay attention to those in order to keep yourself alert. This can actually be a meditation in its own right.

"But if by doing this you don't shake off your drowsiness, then — percipient of what lies in front & behind — set a distance to meditate walking back & forth, your senses inwardly immersed, your mind not straying outwards. It's possible that by doing this you will shake off your drowsiness.

It's hard to fall asleep while doing walking meditation.

"But if by doing this you don't shake off your drowsiness, then — reclining on your right side — take up the lion's posture, one foot placed on top of the other, mindful, alert, with your mind set on getting up. As soon as you wake up, get up quickly, with the thought, 'I won't stay indulging in the pleasure of lying down, the pleasure of reclining, the pleasure of drowsiness.' That is how you should train yourself.

Finally, the Buddha recognized that sometimes you just need to take a nap! The strategies above can help combat and even overcome tiredness, but in the end you're fighting your physiology, and your physiological needs are going to triumph.

There are other techniques for dealing with the hindrance of sloth and torpor, but the Buddha's advice to Moggallana is still very relevant and useful.

No related posts.