Bodhipaksa's Blog, page 22

November 21, 2013

Mindfulness of doors (and more!)

Some of us in Wildmind’s Google Plus community are working our way through exercises from Jan Chozen Bays’ book, How to Train a Wild Elephant. We’re now on week 17 of the book, and this week’s exercise is called “Entering New Spaces.”

Some of us in Wildmind’s Google Plus community are working our way through exercises from Jan Chozen Bays’ book, How to Train a Wild Elephant. We’re now on week 17 of the book, and this week’s exercise is called “Entering New Spaces.”

Here’s a brief outline of the practice:

The Exercise: Our shorthand for this mindfulness practice is “mindfulness of doors,” but it actually involves bringing awareness to any transition between spaces, when you leave one kind of space and enter another. Before you walk through a door, pause, even for a second, and take one breath. Be aware of the differences you might feel in each new space you enter.

This has been one of the hardest exercises for me, because I keep forgetting to do it! I’ll be in the Google Plus community and I’ll read about being mindful while walking through doors, and I’ll think, “Drat! I’ve forgotten to do the exercise. I’ll make sure to be mindful next time I walk through a door.”

Then I forget all about the practice, and at some point I find myself back in the community, get another reminder of the exercise, and have the exact same thought.

So this time I decided I’d just get up and walk through a door just to begin engraving the experience of walking mindfully through a door into my brain, so that I build up the habit.

The experience was lovely: Being aware of approaching the door; mindfully taking a breath; being aware of pushing down on the door handle; being aware of pulling the door open, of stepping through, of being on the other side; mindfully closing the door; mindfully hearing the different sounds in the corridor.

The practice turned into a practice of realizing anatta (not-self) because I had the joyful experience of noticing that the being who arrived in the new space was not exactly the same being that had left the old one. There was no “self” that was transported across the threshold. And that experience was repeated as I stepped back into the office.

I’ve found that “rehearsing” practices is a useful thing to do. For example, you might hear about a practice like paying mindful and compassionate attention to feelings of hurt. (This is something I do — and teach — a lot.) But when someone says something hurtful, your normal automatic defense mechanisms may kick in, and you lose your mindfulness. Maybe you get angry, or maybe you get very upset. Rehearsal can help with that: you can deliberately call to mind an experience that you found hurtful, mindfully notice the sense of hurt, and then direct compassionate and kindly attention to the pain. That way you’re building up an association: feel hurt, be mindful. In time you can engrave that pattern into your brain so that it becomes automatic.

Excuse me a moment while I go walk through a door again…

So there are two things I’m suggesting:

1. Generally, if you want to cultivate a new mindfulness habit, rehearse, either in your imagination (as with becoming compassionate toward feelings of hurt) or by acting out the exercise (as in walking through a doorway).

2. Mindfully walking through doors is a delightful exercise, and if you want to get a feel for just how delightful it is then get up and do it — right now!

PS. And do feel free to join us in Wildmind’s Google Plus community

Related posts:

Mindfulness of hunger

Walking with love (Day 20)

An awareness imbued with compassion (Day 49)

Related posts brought to you by Yet Another Related Posts Plugin.

The Urban Retreat, Day 4: “Protecting oneself, one protects others. Protecting others, one protects oneself.” The Buddha

The Buddha said, “Protecting oneself, one protects others. Protecting others, one protects oneself.”

Lovingkindness helps us protect others, and it helps us protect ourselves.

At one time I used to have the New York Times delivered to my house every morning. It was one of my great pleasures to have a leisurely breakfast with a cup of tea, toast, and some intelligent analysis from the Op-Ed pages. But first I had to get the newspaper, which was tossed onto (or near) the front porch every morning by the delivery driver.

It was always an awkward moment for me walking out onto the porch in my bathrobe and slippers, with my hairy legs and knobbly ankles exposed to the world. I somehow felt judged by the passing drivers. And even though I’m sure they never noticed me, I’d get a bit grouchy as I retrieved my rolled-up copy of the Times.

This was fear, really. It was the fear of what people thought of me, whether they judged me, whether they disliked me or laughed at me. You can tell yourself that all this is silly: that the drivers are too busy driving to notice you, that they’ll probably never see you again, that they’re probably not petty enough to care about how you look. You can tell yourself that it doesn’t matter; even if people have unkind thoughts about you, that’s their stuff, not yours. But still, there’s fear.

Sometimes I’m rather slow on the uptake, and it can take me a while to realize that I’m suffering. So it probably took a few weeks of grumpily retrieving the Times before I noticed what was going on. And my first response, once I did notice that I was suffering, was to wish the passers-by well. As drivers swished by, or as neighbors walked their dogs past the house, I’d slip into saying “May you be well; may you be happy; may you find peace.”

And the fear vanished. Instantly. As long as I kept repeating those phrases, there was no more worrying what people thought about me. There was no grumpiness. There was just me, picking up my paper, feeling joy as I wished others well.

The thing is that there’s no room in the mind for both well-wishing and worrying. If you fill the mind with well-wishing, there’s no mental bandwidth left for worrying what people think about you. And if the fear and the well-wishing coexist, them the fear is lessened.

I highly recommend cultivating lovingkindness at all times — or at least as much of the time as you can. Whenever your mind has room to wander, replace your normal “monkey-mind” thoughts with thoughts of lovingkindness. It provides a kind of mental buffer against anxiety and also against anger and other unhelpful mental states. And in this way we protect ourselves.

And if we do this, then in our interactions with others we’re more likely to take their wellbeing, their needs, and their feelings into account, and we’ll be less likely to cause them suffering and more likely to benefit them. So we protect others, too.

I hope you’re enjoying and benefiting from these Urban Retreat posts. We have plans for many more project like this, and in fact we have eight programs planned that cover the whole of 2014. And in order to help our plans become reality, we’re asking that you make a contribution to the Free Bodhi Fund. In doing so you’ll not only be helping others, but you’ll be helping yourself!

Related posts:

The Urban Retreat, Day 3: When the rubber hits the road

The Urban Retreat, Day 2: Authentic lovingkindness

The Urban Retreat, Day 1: Demystifying lovingkindness

Related posts brought to you by Yet Another Related Posts Plugin.

November 20, 2013

What do you call metta?

What’s your preferred translation of “metta”?

What’s your preferred translation of “metta”?

As a kind of postscript to our recent Urban Retreat, which was on the theme of metta, I’m going to share my thoughts about some of the terms people use, and propose an uncommon, but I think good, English term.

1. Lovingkindness

The most common English term that people use for metta is “lovingkindness.” That’s pretty much the standard term. A search for “metta is loving-kindness” on Google brought up 17,200 results.

What’s good about it?

It’s an old and well-established term in English. You might be surprised how old it is; it’s found for example in a 1611 translation of the Bible (this example is from the Book of Psalms):

I have not concealed thy lovingkindness and thy truth from the great congregation.

Withhold not thou thy tender mercies from me, O Lord:

Let thy lovingkindness and thy truth continually preserve me.

What’s not so good about it?

Well, how often do you hear people who aren’t Buddhists talking about “lovingkindness”? It’s a rare term, and because it’s rare it doesn’t resonate much on an emotional level. And so it’s rather abstract, and ends up suggesting that metta is something remote from our everyday experience; something we’ve yet to experience.

2. Love

Love is again less common than lovingkindness. A search for “metta is love” on Google brought up 34,800 results.

What’s good about it?

We can all resonate with the word “love.” It’s a very warm and emotional term.

What’s not so good about it?

The word “love” is very ambiguous, and we’re always having to qualify it in various ways, by specifying that it’s “non-romantic love” for example (but even that’s very ambiguous, because there are many kinds of non-romantic love, including love of our children, love or our country, loving chocolate, etc.).

And even the “love they neighbor” kind of love doesn’t necessarily fit very well with what metta is. For example, can you love your neighbor but not like them? Possibly, but it’s not very obvious to everyone what that means. But you can have metta for someone you don’t like.

Also, “love” is very much understood as an emotion — something we feel — while metta is a volition or intention — something we want. Specifically, metta is wanting beings (ourselves included) to be well and happy.

Which brings up another problem. “Self-love” has a bad reputation in the west, and it conjures up narcissism and arrogance.

3. Friendliness

Friendliness is less commonly used than lovingkindness as a term for metta, but it’s not uncommon. A search for “metta is friendliness” on Google brought up 2,180 results.

What’s good about it?

Friendliness is a good translation of metta, because it’s related to the P?li word mitta, meaning friend. Metta isn’t about friendship, but it is about friendliness. It has the advantage of being a word in common use, and it’s one that we can relate to more easily than lovingkindness. Friendliness again is more of an attitude or intention, which is closer to metta’s role as a volition.

What’s not so good about it?

The word friendliness sounds a bit weak, and metta can feel quite intense (although it doesn’t have to). What do you think of when you call the word “friendliness” to mind? What images do you see? I see someone at a party, socializing, which isn’t really what metta is about.

4. Universal Love

It’s a term that used, although “metta is universal love” brings up only 9 results on Google. It’s found in books going back to the early 20th century, and I think it used to be more common. In my early days of practice, people would often say that metta was universal love, or universal lovingkindness.

What’s good about it?

Well, technically metta is an unbounded (appam??a) state of mind, which is to say that it’s not “bounded” (pam??a) by conditional relationships, which the word “universal” tries to communicate.

What’s not so good about it?

However, anything that’s “universal” seems pretty much out of reach. What images come to mind when you think of “universal love”? Are those images related to your day-to-day experience? “Universal love” suggests a degree of love that’s almost unimaginable. Sure, you have days when you’re in a good mood and you feel affection for lots of people, but do you love everyone? Every single person? That’s what the term seems to suggest. And probably because that seems to unattainable, “universal love” isn’t very popular as a translation for metta.

5. Kindness

Metta isn’t often translated as “kindness.” The phrase “metta is kindness” only brought up 88 results on Google.

What’s good about it?

Kindness is, like love, an almost tangible quality. It’s something we’ve all felt. We know we’ve experienced it within ourselves, and we can think of examples of people we know who are kind. And kindness is as much an attitude as an intention. What images come to mind when you think of kindness? I think of ordinary everyday situations, with one person being helpful and loving toward another person — perhaps someone who’s in trouble. So kindness is close to compassion, which fits with metta as well, since metta is the basis of compassion.

What’s not so good about it?

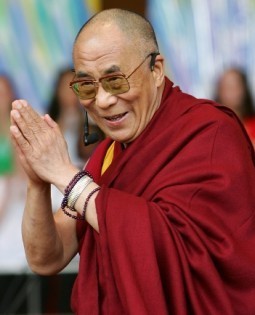

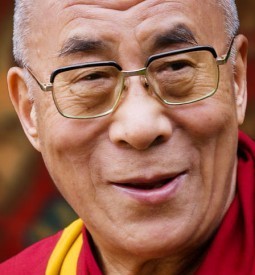

“My religion is kindness.”Not much, in my opinion. Of all the terms we can use to translate metta, I think kindness is the most accessible, in that it’s part of our daily emotional experience. It’s easy to picture it. Think of the Dalai Lama’s smiling face: I think of his face as expressing great kindness. I think it’s closest in terms of describing a volition or intention: with both kindness and metta the intention is to help others find happiness. It does have a feeling quality about it — a sense of warmth and gentleness — but kindness is more defined by our intention and action than is the word love. Kindness is less ambiguous than love, and less over-used. It’s more palatable to think in terms of being kind to oneself as opposed to loving oneself.

“My religion is kindness.”Not much, in my opinion. Of all the terms we can use to translate metta, I think kindness is the most accessible, in that it’s part of our daily emotional experience. It’s easy to picture it. Think of the Dalai Lama’s smiling face: I think of his face as expressing great kindness. I think it’s closest in terms of describing a volition or intention: with both kindness and metta the intention is to help others find happiness. It does have a feeling quality about it — a sense of warmth and gentleness — but kindness is more defined by our intention and action than is the word love. Kindness is less ambiguous than love, and less over-used. It’s more palatable to think in terms of being kind to oneself as opposed to loving oneself.

So, out of all the possible options for words to translate metta, my vote is for that simple, accessible, appealing word, “kindness.”

What do you think?

Related posts:

Metta-blast to the past (Day 4)

Looking with a loving gaze (Day 3)

Struggling with a “lack of lovingkindness” (Day 7)

Related posts brought to you by Yet Another Related Posts Plugin.

The Urban Retreat, Day 3: When the rubber hits the road

When the rubber hits the road is a great time to practice lovingkindness, and I mean literal rubber and a literal road.

There’s a lot of irritation involved in driving, even far short of the extreme of road rage. It can be irritating to be in slow traffic, or busy traffic, or to be cut off, or to be held up by roadworks, or stuck at traffic lights.

We’re emotionally cut off from other drivers because we’re all in our own semi-private metal boxes, and so we don’t have access (usually) to their body language and facial expressions. So we often take things personally that aren’t necessarily personal. As comedian George Carlin said, “Have you ever noticed that anybody driving slower than you is an idiot, and anyone going faster than you is a maniac?”

And the mind wanders when we’re driving. We drive “on autopilot” and the mind gets distracted. And you might think that the mind, having meandered away from the unpleasant grind of the daily commute, would find something enjoyable to think about. But research shows that most of the time we think about things that make us even unhappier! So our internal experience is unpleasant, and we don’t much like what’s going on around us.

Next time you get a chance, look at drivers’ facial expressions. They’re often frowning, or at best neutral. You’ll rarely see anyone smiling while they’re driving. It’s a serious business. It’s an unhappy business, for the most part.

Driving lovingkindness practice can liberate us from all this. When I do driving lovingkindness, I keep myself mindful by remaining aware of my surroundings, and I say the phrases, “May you be well, may you be happy,” as I drive along. Sometimes it’s “May all beings be well, may all beings be happy.”

I might just have a sense that I’m imbuing my field of awareness with lovingkindness in this way, and every perception of a person (or a vehicle that a person contains) is simply touched by my kindly awareness. Or I may focus my attention on various vehicles as they pass in either direction, and wish the drivers and passengers well.

This can become very joyful. One of my meditation students wrote:

For my entire 30 minute ride to work I sent lovingkindness to each passing driver on the road. I can’t tell you the effect the that it had on me … I felt like a protective mother sending all of her children off on their day.

That’s rather lovely.

It’s so much more satisfying to wish drivers well than to have thoughts of ill will about them. When I’m driving with lovingkindness I find I want to let drivers merge, and it feels great. I can see why the Buddha described lovingkindness as a “divine state” — I feel like a gracious deity bestowing blessings as I slow down to create a space for a driver to enter the road. Even if it looks like the other driver is trying to cut the line, I have a sense of magnanimity and forgiveness as I let them in. It feels so much more enjoyable than trying to “punish” the driver by refusing to let them cut in.

And the act of well-wishing also helps prevent the mind from wandering into areas of thought that cloud my sense of well-being. The constant stream of thoughts like “May you be well, may you be happy” make it much harder for my mind to drift. So, despite some people’s fears to the contrary, I find I’m able to pay more attention to my driving, because I’m not getting lost in thought.

And smile! Smiling helps activate our kindness, and it makes us happier. And if some driver or pedestrian happens to see us smiling, they may be reminded that life doesn’t have to be cold, grim, and distracted, but can be warm, kind, and mindful.

Related posts:

Lovingkindness: when the rubber hits the road (Day 21)

The Urban Retreat, Day 2: Authentic lovingkindness

The Urban Retreat, Day 1: Demystifying lovingkindness

Related posts brought to you by Yet Another Related Posts Plugin.

November 19, 2013

"I meditate every day…"

These cool wristbands arrived at our office this morning. They're a reminder of daily practice, for use on the meditation challenges we're running next year as part of Wildmind's Year of Going a Deeper: http://www.wildmind.org/going-deeper

Related posts:

Meditate for Peace Day

When murderers meditate…

A new arrival…

Related posts brought to you by Yet Another Related Posts Plugin.

Documenting a doomed city

Reshared post from +Brent Huffman

Filmmaker risks life to document ancient Afghan Buddhist city’s imminent destruction

This post has been reshared 1 times on Google+

View this post on Google+

Related posts:

Free Market Jesus speaks…

"The rules are: I go first, and I refuse to take my turn

Bright fall leaves on a gray day…

Related posts brought to you by Yet Another Related Posts Plugin.

Inequality and the farm bill

The Insanity of Our Food Policy

How America’s agricultural programs increase inequality at home and abroad.

Related posts:

Inequality and anxiety

Trying hard to have compassion for Bill Kristol

Even Bill Gates seems to hate Windows

Related posts brought to you by Yet Another Related Posts Plugin.

The Urban Retreat, Day 2: Authentic lovingkindness

In yesterday’s post I talked about the fact that many people have misconceptions about what metta (lovingkindness) is, and how those misconceptions can lead to disappointment, despair, and to giving up on the practice. The main misconception I addressed is that lovingkindness is an emotion. Actually, lovingkindness is a volition. It’s classically defined as the intention that beings be happy. So it’s something we want, not something we feel. Although the volition may lead to certain feelings, like warmth, an open heart, a sense of cherishing, joy, etc., the feelings are secondary.

Another thing that often happens is that we try too hard to make something happen. This may have happened to you if you’ve been under the impression that metta is an emotion. You think you’re “meant” to feel an emotion, and so you try really, really hard to make something happen. Perhaps you even succeed at times.

And sometimes people think that metta in daily life involves “being nice” in a false way. But that’s not the case.

Actually, genuine lovingkindness involves, well, genuineness. It involves being honest about what we feel. It involves being authentic.

So the way I teach the practice, I stress the importance of accepting where you’re starting from. At the start of your practice, as you check in with yourself in order to ground the mind in the body, and to see what you’re working with, whatever you happen to find — that’s fine. If you’re feeling happy and loving and expansive, then of course that’s fine. If you’re feeling down, that’s fine. If you don’t know how you’re feeling — that is you’re feeling neutral — then that’s fine. Every feeling is fine. As I like to say, the only place you can start is the place you are, which makes where you are the perfect starting place.

So this is the start of authentic lovingkindness. We accept whatever we find at the beginning of the practice.

Then as we work on cultivating metta, we do this in an authentic way as well. We don’t try to make anything happen. If you use the approach that I suggested yesterday, which involves connecting with the fact that you want to be happy, and that happiness is elusive, then this is authentic as well. We just drop those thoughts into the mind, and see what happens.

Often what happens is that our defenses dissolve away. We forget we want to be happy, even though he yearning is there all the time. It’s a kind of defense mechanism; happiness is elusive, so just ignore it. Or we tell ourselves that we are actually happy (even when we’re not) because it feels like not being happy is a sort of failure. So that’s another defense mechanism. So all we do is we drop these thoughts in — “I want to be happy; happiness is hard to find” and let their truth become evident. We don’t try to convince ourselves of these truths — we already know them. What we need to do is to reconnect with them.

And as we reconnect with these truths, there may be, as I mentioned yesterday, a sense of tenderness and heartache. And in the spirit of authenticity we accept that as well. It’s OK to feel discomfort. It’s not a sign that there’s anything wrong, or that we’ve failed.

And then as we’re cultivating lovingkindness for others, we similarly don’t try to make anything happen. We just drop in the thoughts, “May you be well; may you be happy; may you find peace” and see what happens. Maybe we’ll feel something that we call “love” — but maybe not. It really doesn’t matter. It’s the intention — the wanting others to be happy — that’s the main thing. And even if that intention doesn’t seem to be strong, it’s actually the cultivating of the intention that’s the main thing. As long as you keep doing the practice, things will shift.

As we cultivate the intention of lovingkindness in this way we may find that there are various feelings that arise. We may find ourselves bored. That’s OK. Just accept it. Allow the boredom to be there, but don’t let it determine how you act; continue to cultivate lovingkindness for the other person. This particularly applies to the neutral person, although it can happen in any stage of the practice.

You may feel hurt or unsettled as you call to mind the difficult person. That’s fine. Just be with the discomfort, mindfully and with self-compassion, and keep wishing the other person well. You don’t have to like someone to wish them well.

So all through the practice there’s this attitude of authenticity. We can’t control how we feel, so we don’t try. But we can control (to an extent) what we do, and what we do is to cultivate this attitude of wishing beings (ourselves included) well. The more honestly and authentically we can do this, the more effective the practice will be.

Related posts:

The Urban Retreat, Day 1: Demystifying lovingkindness

Join the Urban Retreat, Nov 9–16

Struggling with a “lack of lovingkindness” (Day 7)

Related posts brought to you by Yet Another Related Posts Plugin.

November 18, 2013

How charitable…

Wal-Mart Asks Workers To Donate Food To Its Needy Employees

A Cleveland Wal-Mart store is holding a food…

Related posts:

Guided meditation Hangout on Air

A guided meditation #throughglass

Free Market Jesus speaks…

Related posts brought to you by Yet Another Related Posts Plugin.

“Let everything happen to you: beauty and terror. Just keep going. No feeling is final.” Rainer Maria Rilke

A woman on the Triratna Buddhist Community’s Urban Retreat, which this year focused on the theme of cultivating lovingkindness, or metta, asked a question about how to deal with “strong emotion” — especially grief — that may arise during lovingkindness practice. For this person, grief tended to arise particularly while she was cultivating lovingkindness toward herself, and she wondered how to be honest with her experience but not dissolve into and become lost in it.

A woman on the Triratna Buddhist Community’s Urban Retreat, which this year focused on the theme of cultivating lovingkindness, or metta, asked a question about how to deal with “strong emotion” — especially grief — that may arise during lovingkindness practice. For this person, grief tended to arise particularly while she was cultivating lovingkindness toward herself, and she wondered how to be honest with her experience but not dissolve into and become lost in it.

I offered he a few suggestions, which I’ll enlarge on here:

1. Stop considering grief as an emotion.

Is grief an emotion? Is “emotion” even a meaningful term, in the context of Buddhist practice?

Increasingly I find the word “emotion” to be an unruly and overly broad category. It’s not a traditional Buddhist term, and I tend to avoid it. Buddhism talks about vedana, or feelings, but these don’t overlap very well with our term “emotion.” Vedanas are a primarily a sense of whether something is pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral. They’re our evaluation of something we’ve perceived: look out of the window and see rain, feel your heart sink; see the sun come out from behind a cloud, feel a rush of joy. Those are things we’d often call “emotions.”

Buddhism also talks about cetana, which is volition or intention. Metta (lovingkindness) is the desire that beings be happy, and the intention to act in a way that makes them happy. Anger is the desire to hurt, or wound, or to destroy an obstacle. So we might often call cetanas “emotions” as well.

But from a Buddhist point of view, vedanas/feelings and cetanas/intentions are completely different things! We can’t directly choose what feelings arise, but we can choose what intention we’re going to put our energy into. For example, you can’t choose not to be hurt by a cutting comment, but you can choose not to express or reinforce our anger, and instead to focus on being kind. Feelings are part of out “input” (i.e. experience that arises in consciousness) while intentions are what lead to output (i.e. actions).

So our term “emotion” covers two different phenomena in an unhelpful way.

Also, some intentions may not have much feeling associated with them. We can be kind to others without actually feeling anything like love. We might even feel rather depressed, but still want to act in a way that’s helpful and considerate to others, and we wouldn’t want them to suffer. This confuses people sometimes when they’re practicing meditations in which they cultivate lovingkindness. They look for something resembling an “emotion” of love (gushing warmth in the heart, a feeling of radiance) and don’t find it. So they think they’re doing the practice wrong and don’t have any of this “thing” called lovingkindness. Actually, they have the intention for beings (including themselves) to be happy, so they have plenty of lovingkindness.

So that’s why I tend these days to avoid the word “emotion” and to stick to the traditional terms vedana and cetana, or their translations, feeling and intention.

And I suggest that the primary experience of grief is what Buddhism calls a vedana. It’s a feeling. In this case it’s an unpleasant feeling, and it usually arises when something we’ve loved or clung to has been lost. Sometimes we’re not even conscious that we have lost anything, so grief can seem to arise randomly.

2. Accept your feelings.

Since vedanas are not something we consciously do, they are ethically neutral. Ethics, in Buddhism, is about intention. Grief is therefore ethically neutral, and so it’s not something we should try to rid ourselves of. It’s not “bad” to experience grief. It’s just uncomfortable.

But what we call grief can also have a volitional, or intentional, aspect to it as well. After the primary experience of grief comes our response, which can include aversion, or thoughts about how this experience shouldn’t be happening, or how we just want it to go away, or we think that we’ve “failed” because we’re suffering, etc. Those are all volitions, and they intensify our suffering. Every time we respond to our initial experience of grief with a thought akin to “woe is me,” a new wave of unpleasant feeling is generated.

The initial grief — the first pang — that we experience is what the Buddha called the “first arrow” of suffering. Our resistance, etc., is the “second arrow,” which we fire ourselves, and which adds to our pain.

So first of all we need to accept that the grief is there, and that it’s OK to feel it, even if it’s unpleasant. You can even say to yourself, “It’s OK to feel this.” So we keep dropping all the “second arrow” volitions, thoughts, and actions, and mindfully pay attention to the grief as best we can.

3. Cultivate self-compassion.

But we can also have compassion for our own pain. This doesn’t mean wallowing (that would be the second arrow again) but simply recognizing that there is a part of us that is in pain, and giving it our kindly and loving attention. You can locate where, in the body, the grief is principally located. (It’s often the solar plexus). And you can wish your pain well, as you would to a friend in the metta bhavana practice. You can even place a hand on the place where the grief is manifesting and say something like “I love you, and I want you to be happy.”

Rilke’s statement, “Let everything happen to you: beauty and terror. Just keep going. No feeling is final.” is very apropos, but it might suggest to some people being overwhelmed by feelings. Allowing yourself to be overwhelmed is not what Rilke is suggesting, though, since he also advises us to “just keep going.” When we’re lost in our feelings we become passive and so we give up on the “going.” The feeling becomes the only thing we can know or see. When we “just keep going” we’re aware that we’re going through a process that will naturally end. The more we resist our feelings, the longer the process will take. The more we can accept them and have compassion for them, the more quickly they’ll pass.

“No feeling is final.” Every feeling we have ever had has arisen and passed away. It came from emptiness and returned to emptiness. This is true for whatever you’re feeling right now. That anxiety, that dread, that feeling of hopelessness and despair, that grief — it’ll pass. Just accept it, and give it your compassion, and help it on its way.

Related posts:

“Perhaps everything terrifying is deep down a helpless thing that needs our help.” Rainer Maria Rilke

Sorrow is failed compassion (Day 28)

Even-mindedness and the two arrows (Day 79)

Related posts brought to you by Yet Another Related Posts Plugin.