Brendan I. Koerner's Blog, page 36

September 12, 2011

Demo or Die

Let me start the week by directing y'all's attention to my latest Wired essay, in which I argue for the revival of a bygone regulation: the requirement that patent applicants submit working models of their inventions. Sound onerous? Yeah, that's the point:

The abolition of the model requirement [in 1880] was initially a boon to backyard inventors, who often lacked the capital to build detailed mock-ups of their visions. But as America's population of skilled engineers has exploded, the patent system's low barrier to entry has become its fatal flaw. The USPTO received 520,277 applications in 2010, a figure up nearly 500 percent since 1970. Countless inventions of dubious value or debatable novelty slip through this overwhelmed system, leading to endless litigation that has become a serious drag on American industry. "The requirements to patent have become, in my humble view, a joke," says Mario Biagioli, a history-of-science professor at Harvard University.

The USPTO could instantly slash the number of applications by compelling inventors to submit working models whenever feasible. The most abstract inventions would be exempt, of course, but these constitute a small minority of applications; business models, for example, made up about 2 percent of the patents issued last year, and drug compositions were roughly 3 percent. The bulk of inventors would have to come up with three-dimensional examples of how their creations would look and function. Have a great idea for a longer-lasting semiconductor? A sturdier toxic-waste container? A safer lawn dart? Don't just submit a diagram; make a model the examiner can touch.

The idea for this essay grew out of a dialogue started by my boss Chris Anderson, who posited that the tech industry ascribes too much value to mere ideas. Without the organizational chops to realize that vision, he argued, an idea is a trifling thing. That contention got me thinking about readjusting the patent system in order to reward a skillset beyond mere creativity. Re-establishing the model requirement would compel inventors to prove that they can work well with others, which is the real key to translating ideas into tangible goods.

It's a notion that certainly doesn't gibe with our vision of the lone inventor making magic in his garage. But that was always just an illusion—what, you think Thomas Edison worked alone?

September 9, 2011

The Ponchos: A PG-13 Masterpiece

I can probably count on two hands the number of movies I've paid to see twice in a movie theater. Virtually all are classics that I've caught as revivals: The Godfather II, A Clockwork Orange, and The Bridge on the River Kwai immediately pop to mind. But there is also a decided oddball in the mix, a movie that no one in their right mind would consider worthy of being mentioned in the same breath as the works of Kubrick and Lean: the 1987 teen comedy Can't Buy Me Love, a flick that is mostly memorable for its odious plot.

For those too young to remember the twilight of Ronald Reagan's second term, Can't Buy Me Love was the tale of a high-school outcast who paid a mega-popular cheerleader to date him for a week, as a way of climbing the local social ladder. The fundamental lesson of the movie is that a pretty girl will chastely whore out her affections in exchange for several hundred bucks, provided she's desperate enough or cash. An ugly moral, but one my grade-school self wasn't nearly smart enough to understand. I was just thrilled to be watching a flick that was rated PG-13—it made me feel mature beyond my years. And so my pal and I ended up catching the movie twice, after getting dropped off at the multiplex by his extremely permissive dad. For two kids who were just beginning to figure out that girls were not, in fact, the enemy, Can't Buy Me Love was the closest we could get to an illicit thrill.

I remember little about the movie today, save for the line uttered above by Patty, the stereotypical class tramp. Finding herself alone in a car with the protagonist, now considered quite the catch after his fake dalliance with Miss Cheerleader, she makes her move by uttering a line demands recognition with a Poncho, Microkhan's award for memorably uttered lines by supporting characters. For those of you who can't safely YouTube right now, the decidedly PG-13 sentence is as follows:

I happen to know in the whole school, there's only one other titty quite this pretty.

It wasn't the naughtiness of the line that struck my grade-school self; it was the fantastic delivery by actress , who raises her voice to a geisha-like lilt as she hits the word "quite." Then there's the way she touches her fingertip to the corner of her mouth, suggesting depths of lewdness that no PG-13 movie could possibly explore.

Pure theatrical genius—a masterclass in playing the floozy in her prime. I highly recommend that all actress asked to play women of loose morals study DeMoss's performance in the same way that aspiring military commanders study Võ Nguyên Giáp's tactics at Dien Bien Phu.

September 8, 2011

With Friends Like These

As Muammar Qaddafi continues to rage, rage, rage against the inevitable dying of the light, the time has come to assess just how much damage he wrought during his absurdly long rule. I never cease to be amazed by the man's longevity; just recently, in fact, his name came up in my book research, as a man who was said to extend offers of hospitality to American fugitives. He briefly flirted with the idea of turning Tripoli into a North African version of Havana, a base of operations for on-the-lam radicals whose ability to escape justice might prove deeply embarrassing for the United States. But like many a megalomaniacal strongman, Qaddafi had an incredibly short attention span. Before he could set the wheels in motion on his anti-American plan, he moved on to another pet project: aiding the Irish Republican Army in its fight against the British.

Ultimately, this sort of half-baked approach to policy will be Qaddafi's legacy. The man was big on concepts—albeit dastardly concepts—but laughably awful at follow-through. Uganda knows this well, based on Qaddafi's lame attempt to prevent his pal Idi Amin's overthrow in 1979. Libya sent plenty of troops to Uganda, to stave off a Tanzanian force bent on ridding its neighbor of Big Daddy's murderous influence. But no one seemed to make any plans beyond simply loading the soldiers onto a Kampala-bound plane—which is why the bodes of so many Libyans now fill mass graves in Uganda:

The arrival of the Libyan desert commandos was as surprising as it was annoying because we had made it all along clear to Amin and the entire Army top brass that all we needed was artillery fire power to neutralise the enemy's Katyusha and not the personnel. Communication was the biggest problem. They could neither communicate in English nor Swahili. Attempts to use Nubian which is more like broken Arabic hit a dead end because they could not understand the dialect. We resorted to communicating by hand.

"Another problem was in the dressing and the arms that the Libyan commandos opted to use. Their clothes were clearly not for jungle warfare. Instead of arming themselves with assault rifles like G3s and AK47s, they had light arms like Uzi guns and a wide range of machine pistols. We did not have any way of informing them that their clothes and arms were going to work against them, so we simply let them go to the front. They joined our forces that were waiting for the enemy in Kalisizo. The enemy descended upon the area in full force. The battle was hot for both our troops and the Libyans, who suffered because of their failure to comprehend withdrawal orders issued in Swahili.

The following morning when some of them came back to Masaka after the fall of Kalisizo, they were a sad sight. Some were dead and many of them were injured. It was a pitiful scene watching those who were lucky to escape without any injuries tearfully carrying their wounded and dead colleagues off their small trucks.

History does not seem to have recorded Qaddafi's reaction to this slaughter. My guess is that by the time the news reached his ears, he had more-or-less forgotten that he'd ordered the mission in the first place.

September 7, 2011

An Appeal to the Rain Gods

Supposed to be taking Microkhan Jr. to his first major league baseball game today, an afternoon Yankees-Orioles tilt up in the Bronx, but the weather is looking ominous. I thus aim to curry favor with the rain gods by posting the song above from Max Tannone's much-beloved Ghostfunk, recently highlighted on perennial podcast fave Fresh Produce. Because we all know how much weather-controlling deities enjoy Wu-Tang remix projects. I also hope they are fond of keeping little boys' hearts intact; the kid will be crestfallen if we're forced to end up at the Chuck E. Cheese in Harlem.

September 6, 2011

A Pro's Pro

At the risk of alarming folks who have a vested interest in my creative progress, I must confess that the book-writing process is proceeding at a snail's pace. In a wildly optimistic moment last month, I vowed to have two entire chapters done by Labor Day; now my best-case scenario is that I'll have a single chapter done by day's end, and even that isn't a lock. The words flow much more quickly in theory than in practice.

Yet as much as I'd like to convince myself that all writers endure such struggles, that simply isn't the case. I found it alternately illuminating and dispiriting to read this terrific 1984 interview with The Godfather author Mario Puzo, who was nothing if not productive. Prior to finding his fortune in Hollywood, Puzo labored as a pulp-magazine writer, penning sensationalist clip jobs under the pseudonym Mario Cleri (above). He spoke of just how many pages he could dash off in the name of pulling a family-sustaining paycheck:

Q. How many pages of a book bonus could you write in a typical day?

PUZO: I used to do a book bonus on the weekends, which was at least 60 pages. I never could write in the office, I had to work at home. When I was working on The Godfather, I was doing three stories a month, I was writing book reviews for The New York Times, Book World, Time magazine, and I wrote a children's book [The Runaway Summer of Davie Shaw]. All at one time. And I was publishing other articles. I had four years where I must have knocked out millions of words.

I tell ya, it's absolutely the best training a writer could get, to work on those magazines. You did everything.

Q: There's no equivalent today.

PUZO: It's a shame. If I had a son who wanted to be a writer, I wouldn't even bother to send him to college. I'd get him a job up there as an assistant editor, leave him there for five years and he'd know everything. You've got to turn out a lot of copy.

Also worth noting from the interview, especially given the subject matter of my book: Vietnam didn't play in the pulp world:

Q. Did you ever write a story on Vietnam?

PUZO: Yeah, I did one or two, but they were absolute poison. The readers didn't like to read about it. That was very early on in Vietnam. We used to emphasize that Vietnam only had poison sticks. How the Poison Stick Army Beat America's Ultra-Modern Weapons, shit like that.

Q. But it never went over?

PUZO: Nah, they hated it. Also we weren't the heroes. Just like the Korean War—we used to call that The No Fun War. World War II was The Fun War. And you could get some mileage out of the Civil War and World War I. World War II was a bonanza. But Korea and Vietnam were losers.

I wish the interview had delved a bit more deeply into the notion of what constitutes a "Fun War," and whether such a thing is even possible in the age of mass communication. Copious information creates a thousand shades of moral gray.

September 2, 2011

Face Off

When you've spent the better part of your adult life at the helm of an entire country, it must be awfully hard to accept a gold watch and fade into the sunset. I'm going to guess that playing bridge, hitting the country-club buffet, and working on your memoirs doesn't give a type-A personality the same sort of thrill as hobnobbing with heads of state. So how many of us can be surprised to hear that Sir Michael Somare, the longtime prime minister of Microkhan fave Papua New Guinea, is having second thoughts about relinquishing his hold on power:

PAPUA New Guinea's founding father and former prime minister Michael Somare will take up his seat when parliament sits again next Tuesday, his son Arthur said yesterday…

Earlier, Sir Michael's daughter Bertha had emailed a media statement from Singapore, where he is recovering from three heart operations since April.

The statement, accompanied by Sir Michael's signature, said: "Let me be clear. I am ready, willing and able to complete my term as the only legally elected prime minister of Papua New Guinea".

It quoted Sir Michael, 75, as saying: "There has never been a vacancy in the position of prime minister."

That last bit is certainly news to Papua New Guinea's parliament, which declared the prime minister's post vacant in early August, upon learning of Somare's serious health problems. Peter O'Neill was elected in Somare's stead, and the cockeyed optimists among PNG watchers were hoping he might finally do something about the nation's endemic corruption and lack of security.

If Somare does show up on Tuesday as promised, the showdown on the parliament floor will make for some excellent political theater. Does anyone know if PNG's equivalent of C-SPAN has a live Internet feed?

September 1, 2011

The Original Social Networks

For those of us born after the invention of pencilin—presumably anyone and everyone who has ever checked into Microkhan's universe—it's difficult to fathom the esteem in which fraternal organizations were once regarded. Thumb through any society page from the first half of the 20th century and you'll doubtless encounter one article after another about the estoerica of Kiwanis or Roatarian politics—the fierce squabbles over leadership positions, the spats over the right date on which to hold the annual potluck. In the era before cheap travel and mass communication enabled businessmen to strike deals with people who lived beyond their county's borders, the ties created by fraternal bonds were integral to making commerce happen—and, one suspects, to giving men an outlet for energies that are currently expended on professional football and Internet pornography.

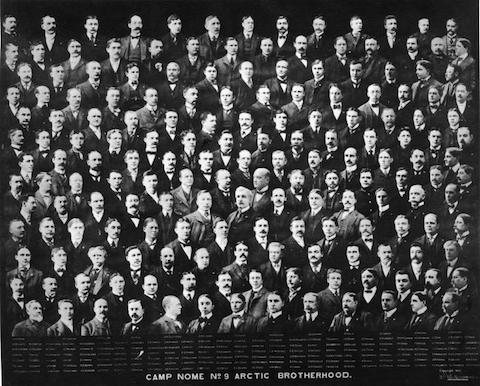

It makes perfect sense, then, that Alaska's early white settlers transported the fraternal-organization concept to their new homes. The foremost of the resulting clubs was the Alaskan Brotherhood, founded in 1899, which managed to garner over 10,000 members before it disintegrated in the late 1920s. Because of the lack of leisure options in the frozen north, the organization was fond of staging shows—some of admirable quality, others that were appallingly racist.

The Arctic Brotherhood may have lasted until the dawn of the Great Depression, but its heyday was brief—everything went downhill after 1909, when a schism occurred over the question of whether residents of the Lower 48 could be allowed to join, even on a ceremonial basis. The Dawson Daily News covered the controversy:

Considerable agitation is evidencing itself in the local Arctic Brotherhood circles over the news that Bill Taft is to be initiated down in Seattle along with about 200 others who are trying to climb in the band wagon when the president rides the goat, and there threatens to be a mighty upheaval is this desecration of the brotherhood's ideals is really pulled off.

There are shades here, of course, of controversies of more recent vintage, concerning some radical Alaskans' antipathy toward those scoundrels in the Lower 48.

Much more Arctic Brotherhood history on the site of its modern incarnation.

(Image via Alaska's Digital Archives)

August 31, 2011

The Underwhelmer

Hacking my way through a tricky part of the book today—a section in which I must encapsulate the tumult of late-1960s South Vietnamese politics in the space of two paragraphs. The chore has me focusing on the figure of Nguyen Cao Ky, the air marshal who became South Vietnam's prime minister in 1965 (and who recently passed away). While his achievements, or lack thereof, have been long debated, one thing is for sure: Nguyen had no illusions about his capabilities, as evidenced by his memories of the post-coup military meeting that brought him to power:

I asked all of [the officers] — 60 or 70 of them, you know, in the room. I said, "Okay — ah, one more time. Anyone want to be prime minister?" And they said no. So [Gen. Nguyen Van] Thieu said, "I propose Ky." And all of them just stood up and accept the offer. But then I, I didn't give them the answer. I said, "I have to go back and talk with my wife first." And when I told her about that offer, you know, she was not excited. She said, "Oh no! Not that job! Not as a prime minister!" Ha, ha. I'm not a good politician. I'm not a good diplomat. You know, I think all I know, the only thing I can do well is, you know, flying the airplane. I said, "Well? What can I do now?"

On the plus side, he did end up giving the world a daughter who revolutionized the world of Vietnamese-language aerobics.

August 30, 2011

Commerce Above All

Those who've been keeping score might have noticed a recent Microkhan obsession with visual communication—particularly the way in which simple illustrated material can be used to convey complex messages. This is an interest that dates back to my first exposure to Chick tracts, and has now ramped up with all the energy I've been pouring into evaluating the efficacy of wartime propaganda.

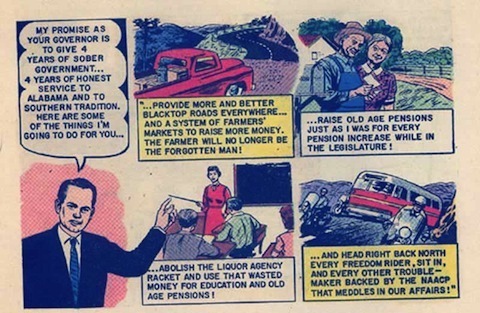

My latest discovery on this front raises a different, more philosophical issue: how some people are able to divorce their personal beliefs from their business, and some are not. Comic-book creator Malcolm Ater certainly fits into the former category. His Commercial Comics Company seemed perfectly willing to create tales for any paying customer, from the American Gas Association to the Congress of Industrial Organizations to George Wallace (above). The story of how the Illinois-bred Ater eagerly spread Wallace's odious message is recounted here:

In 1960 Ater traveled to Alabama to meet with George Wallace, who was running for governor. By Malcolm's retelling, Wallace leaned across his desk and stated "I don't see how a damn Yankee like you can come down here to Alabama and help me get elected." Ater replied "Well, Judge, if you'll recall, I came down here a few years ago and worked for John Patterson and helped defeat you!" Wallace and he became friends and the result was the comic Alabama Needs the Little Judge, George Wallace for the Big Job. This book is pro segragationist and in it Wallace promises to send "back north every freedom rider, sit-in, and every other troublemaker" sent by NAACP.

There is no hint anywhere in Ater's biography that he harbored political views that were anything like Wallace's—if they were, I very much doubt he would have volunteered his services to Madonna in the mid-1980s. And so I find myself wondering whether there was ever a moment's doubt in Ater's mind as to whether he should take the Wallace gig, or if there really is a breed of human who can banish all personal thoughts in the service of commerce.

In a sense, Ater reminds me of the late Lee Atwater, who reportedly only became a Republican in order to rebel against the fact that he was surrounded by Democrats while growing up in South Carolina. The story goes that Atwater didn't care a whit about the issues his candidates espoused—he only cared about winning elections, much as Ater only cared about getting paid to create comics. Is there something quintessentially American about that approach to business?

Another classic (and notorious) Ater comic here. If I had been a schoolkid in Grenada in 1984, I would've been damn terrified of those Cuban monsters.

August 29, 2011

A Fat Lot of Good

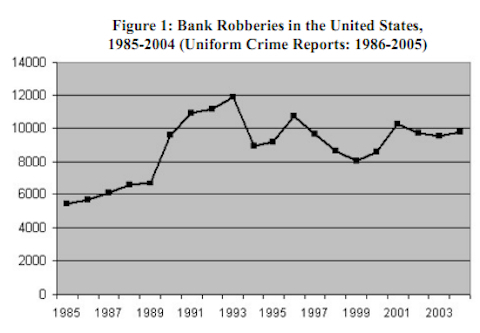

A recent deep-dive into the history of the dye pack got me wondering about long-term trends in bank robbery. So much brainpower has gone into devising gadgets and strategies that allegedly help financial institutions minimize the risk of getting hit. Are those security investments working?

That's a tougher question to answer than I had anticipated, as the basic stats on the crime don't seem too favorable. As you can see above, the sheer number of robberies has increased since the mid-1980s, more than keeping pace with population growth. On top of that, robbers are enjoying ever greater odds of escaping arrest (PDF):

Although the clearance rate for bank robbery is among the highest for all crimes, the rate has declined. In the United States, bank robbery clearances have dropped from 80 percent in 1976 to 58 percent in 2001; clearances vary by region, from as low as 34 percent to as high as 80 percent.

That isn't to say that all those crafty anti-robbery techniques have been for naught. A big factor in the crime's growth seems to be the proliferation of small suburban branches, where police response time is much greater than in central areas. Without innovations such as single-door entryways, dye packs, and greeters, there's no telling how high the rate might be today.

More important, there's some really interesting cost-benefit analysis going on here. The average take from each bank robbery is just around $4,000, and about 60 percent of all stolen money is eventually recovered. A quick back-of-the-envelope calculation thus concludes that American banks lose just around $16 million to robber each year—peanuts compared to liabilities they might face if a botched robbery led to customers' deaths. As a result, there is little incentive for banks to do much to change the status quo—the current situation, in which bank robbery is nothing more than a well-managed risk, suits them just fine.