Brendan I. Koerner's Blog, page 35

September 26, 2011

Primal Joy

Recovering from the flu today, so don't quite have the mental fortitude to do anything more complex than shuffle from coffee pot to couch. But thought I'd muster the energy to share the clip above, the first goal from last week's Fenerbahce-versus-Manisaspor soccer match in Istanbul. For those of y'all who don't follow Turkish sports, it seems there was a bit of violent unpleasantness at Fenerbahce's last home game, and club officials were seriously considering holding the Manisaspor tilt in an empty stadium as punishment for its hooligans. But they decided instead to admit only women and children younger than 12, which resulted in a fan dynamic that's guaranteed to put a lump in your throat. Don't think I've ever heard a post-goal celebration quite that high-pitched. But it works.

Take note, though: At the 2:23 mark, there are definitely a couple of older dudes in the crowd. Wonder if they had to don wigs to sneak in, in sort of a reverse Offside maneuver.

September 23, 2011

A Rare and Monstrous Talent

I'm the early stages of planning a new Wired project, one that will delve into the economics of how to properly compensate "ultra-specialists"—that is, people who possess the unusual ability to tackle extremely arcane tasks. I guess the classic example here would be those left-handed relief pitchers who make millions by appearing in a handful of innings each year. Or programmers who are fluent in outmoded languages, and so need to be paid handsomely to fix snafus in legacy systems that still underpin critical infrastructure.

A great character of yore who made a mint off a strange talent was the man born Saverio Giannone, better known to fans of pugilistic history as Joe Grim. By his own admission, Grim had no fighting skills to speak off—he could barely hit hard enough to break a piece of tissue paper, and his open stance and slow feet made him easy to strike. Yet like Homer Simpson, Grim had an amazing knack for absorbing the worst physical punishment imaginable—his claim to fame was that you simply couldn't knock him out. This great history of Grim's bizarre, loss-filled career includes a fantastic tidbit regarding the man's 1905 run-in with then-rising heavyweight star Jack Johnson:

Even though Johnson weighed 210 to only 165 for Grim, there were still doubts he could put the human punching bag away. Confident of his punch, Johnson had wagered heavily that he'd knock the man out.

Some 3000 people, including Nat Fleischer, future founder of The Ring, paid to see the match in Philadelphia and it would be even money on which fighter was the main draw. In the first three rounds Grim was beaten around the ring. He would drop and the crowd would shout, "Get up Joe!" and Joe would get up, a broad grin on his bloodied face. In the fourth Johnson landed a punch that dropped his opponent to the floor with a thud. Grim waited on hands and knees as the referee counted, then jumped up before the count of "ten". Three more times he went down in the round, three more times he got up. The forth round followed suit, and in his corner, an amazed Jack Johnson declared, "He ain't human."

In the fifth Grim was down six times, three times for a count of eight and three times for a count of nine. Each time he rolled to his belly, climbed to his knees, and waited for the referee to "almost" count him out before rising amid the cheers of the crowd. It wasn't boxing, it was a circus act with the lion tamer letting the lions do their worst, then leaving the cage savaged and bloody to take his bows.

The sixth and final round saw a desperate Johnson trying to win his bets. Jack caught Grim with a right to the chin so hard, as Nat Fleischer said, ". it caused Grim to turn a complete somersault." The referee counted as Grim lay there senseless, some thought dead. It appeared he wouldn't beat the count, but on eight the bell rang, ending the fight and saving Grim from his first knockout. He had been knocked down eighteen times by one of the hardest punchers of his time but he hadn't been counted out. In Grim's mind, the defeat was a victory of the only sort he would ever know. More fights followed and the Iron Man didn't disappoint the fans of that cruder era. He didn't win, but he didn't fail to shout out after the final bell, "I'm Joe Grim! Nobody knocks out Joe Grim!"

Popular lore holds that Grim never actually won a fight, but his thorough BoxRec entry suggests that he tasted the thrill of victory on roughly five occasions—versus 33 losses. How long the sweet memories of triumph existed in his mind is anyone's guess; my hunch is that Grim's mental faculties did not fare well in his post-career years, given the trauma his brain endured in the ring.

(Image via Antiquities of the Prize Ring)

September 22, 2011

The System

Taking a sick kid to the doctor this morning—an hour-plus on the subway, followed by a sure-to-be interminable wait for gruff service. Should be fun.

September 21, 2011

Grunt's Eye View

I never did care much for war comics as a kid, and so always flipped past back issues The 'Nam when searching for the latest Wolverine. But now that the latest book has got me looking for ways to bring the jungles of Long Khanh Province alive, I've found myself relying on some choice The 'Nam panels for visual inspiration. Though the plots tend to be pretty formulaic (bordering on cliched), there's tremendous psychological depth to many of the depictions of combat—the creators do a nice job of creating a brutal juxtaposition between the ideals and realities of war. (Case in point.)

There are also moments throughout the series that focus on the isolating aspects of overseas service—a stressor too seldom mentioned in accounts of soldiers' mental well-being. The military tried to counter those feelings by brining in a never-ending series of beautiful girls in go-go boots to entertain the troops. As depicted in Apocalypse Now, such shows invariably spiraled out of control as the men's libidos got the best of them. But according to this issue of The 'Nam, this seemingly salacious entertainment was fundamentally more wholesome than a typical 4-H fair.

The truth, I'm certain, is somewhere in the middle—isn't it always?

Much more about the lady above, Chris Noel, can be found here; how I wish I could find a second source to verify the claim that the Vietcong put a $10,000 bounty on her head.

September 20, 2011

Pushing the Revolving Door

I can't say I'm a huge fan of The Shawshank Redemption, but there's one scene toward the end that I consider truly memorable. It's the one in which Morgan Freeman, having been paroled from prison after so many years behind bars, is shown at his job in the free world: bagging groceries at a supermarket. Upon feeling Nature's call, Freeman waves a hand at his manager and asks for permission to use the restroom. Slightly embarrassed by the fact that this request was made public, the manager calls Freeman over and informs him that he's free to go and hit the head whenever he pleases.

This gentle reprimand hits Freeman hard—it's the moment he realizes that his decades of incarceration have left him so thoroughly institutionalized that he cannot function in normal society. It's a bitter revelation that I immediately thought of upon reading the tale of Craig Andrew Glen Blair, a career criminal in New Zealand who seems to have decided that he lacks the skills to exist beyond prison walls:

Blair had only been out of prison from a previous bank robbery offence for five days when he decided he could not cope living on the outside.

He had spent all his money on release on alcohol and had lost contact with his immediate family, his lawyer Tim Barclay told the Rotorua District Court.

Blair, 43 made a calculated decision to reoffend just enough to be able to be sent back to jail, he said.

Blair, who had already served a two-and-a-half year sentence for robbing the National Bank in Te Puke in 2008, held up the Westpac Bank in Rotorua in June this year.

He waited in the queue and then approached the teller demanding money, saying he had a gun in his bag. After being handed a "modest" $1140, Blair walked 400 metres to the Rotorua Police Station to give himself up.

At sentencing yesterday Judge Phillip Cooper said Blair had refused any rehabilitative assistance available to him on his release. He also made no attempt to contact his immediate family, which included his adult children, for help.

Prison seems like such a ghastly place to most, so it's very difficult to understand Blair's mindset. Yet at the same time, his seemingly odd choice dovetails with fresh research (PDF) questioning whether incarceration really reduces recidivism. The fact of the matter is that humanity's various systems of justice are all united by our faith in the hierarchy of punishments. But what happens when the facts of life on the outside invert a critical part of that hierarchy—that which holds that prison is a worse fate than supervision in the free world?

September 16, 2011

Where Do We Go Now?

Given how much I write about Papua New Guinea, it would be much to my discredit if I didn't wish the nation a happy 36th birthday before I split for the weekend. Here's to hoping that things start looking up for the country in the post-Michael Somare era; as newly minted prime minister Peter O'Neill noted today with exceptional frankness, there is much progress to be made:

"As a nation we have come a long way in 36 years, but our record is one we cannot be very proud of…Regardless of where you are, look around you. Our infrastructure, like roads and bridges, airports and wharves are in a shamble. We have fallen short of our national goals and principles enshrined in our constitution."

You know what they say: the first step is admitting that you have a problem.

The Eyeball Test

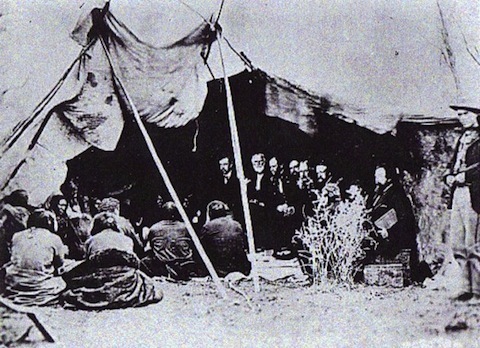

I had to do a double-take this morning when I saw that The New York Times had a (digital) front-page feature on the Freedmen controversy. The question of whether Black Indians deserve tribal membership is something I wrote about six years ago, in a mammoth Wired piece that pondered the role of genetic analysis in this debate. One of the historic details I included in that story is worth noting in light of the Cherokee Nation's that the Freedmen aren't really Indian. It concerns the Dawes Roll, the 1906 census of Oklahoma Indians that the tribes claim is the only acceptable way to document Native American heritage:

The Dawes Roll was the brainchild of a patrician Massachusetts senator, Henry Laurens Dawes, who wanted to "civilize" Indian territory by ending communal land ownership and allotting 160-acre plots to individual members of each tribe. At first, the tribes resisted the white man's efforts to destroy a centuries-old way of life. One Creek official compared the Dawes Commission, which oversaw the roll's creation, to the plague of locusts the Egyptians faced in the Bible. But the tribes relented, if only to avoid a conflict with the US government.

The task of enrolling the Indians was assigned to white clerks dispatched from Washington. They set up vast tent villages in Oklahoma towns and sent word through tribal officials that anyone interested in claiming their land had to register. Once the news spread, the tents were deluged with applicants, including scores of Caucasians claiming to have a sliver of Indian blood. More surprising for the clerks were the thousands of African-Americans who showed up. The 1890 census counted 18,636 people "of Negro descent in the Five Tribes." With no ability to speak any Native American language, the clerks often relied on the eyeball test. Those who fit the stereotype – ruddy skin, straight hair, high cheekbones – were placed on the "blood roll." The roll noted each person's "blood quantum," the fraction of their parentage that was ostensibly Native American. That number was sometimes based on documentation, but often, given the lack of accurate records and the language barrier, it was nothing more than crude guesswork.

Those with obvious African roots were sent to a different set of tents. There, they were added to the Freedmen Roll, which had no listing of blood quantum. Contemporary Freedmen believe the segregation was part of a government conspiracy to steal Indian land. Freedmen, unlike their peers on the blood roll, were permitted to sell their land without clearing the transaction through the Indian Bureau. That made the poorly educated Freedmen easy marks for white settlers migrating from the Deep South. Stories abound of Freedmen, unable to read the contracts they were signing, selling their 160-acre plots for as little as $15.

The haphazard nature of the Dawes clerks' methodology means that there are Freedmen who, at a genetic level, can probably claim to possess more Native American DNA than enrolled tribal members—a fact that gives lie to the Cherokee argument that their stance is meant to preserve a coherent Indian racial identity.

The attendant issues of memory, sovereignty, and meaning are far too complex to unpack in this limited space. But as long as the Cherokees and other tribes insist on clinging to a biological myth perpetuated by early 20th-century bureaucrats, it's going to be hard to take their other concerns seriously. Besides, hasn't history repeatedly shown that nations only prosper when they expand their notion of citizenship beyond mere ethnic affiliation?

September 15, 2011

Tommy Can You Hear Me?

Knocking back a few pints with fellow scribe Doug Merlino last night, the conversation inevitably turned to sports—or, more specifically, the late 1980s heyday of Sports Illustrated, the magazine that taught us both to love the art of storytelling. We both remembered that this vintage era of SI featured a ginormous number of "as told to" yarns, in which troubled athletes relayed their tales of woe through the magazine's best writers. Perhaps the most classic example is Gary McLain's famous mea culpa about his cocaine use, a piece that probably did more to convince me of the drug's wickedness than 10,000 "Just Say No" spots. (FYI, McLain seems to have landed on his feet in the years since.)

Knocking back a few pints with fellow scribe Doug Merlino last night, the conversation inevitably turned to sports—or, more specifically, the late 1980s heyday of Sports Illustrated, the magazine that taught us both to love the art of storytelling. We both remembered that this vintage era of SI featured a ginormous number of "as told to" yarns, in which troubled athletes relayed their tales of woe through the magazine's best writers. Perhaps the most classic example is Gary McLain's famous mea culpa about his cocaine use, a piece that probably did more to convince me of the drug's wickedness than 10,000 "Just Say No" spots. (FYI, McLain seems to have landed on his feet in the years since.)

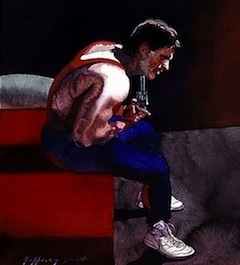

The anti-drug story that occupies an even more prominent place in my memory banks, though, is the 1988 tale of Tommy Chaikin, a South Carolina football player who essentially lost his mind to steroids. The opener is a classic—a well-crafted shocker that still makes you believe that you're reading Chaikin's thoughts, not those of his co-writer:

I was sitting in my room at the roost, the athletic dorm at the University of South Carolina, with the barrel of a loaded .357 Magnum pressed under my chin. A .357 is a man's gun, and I knew what it would do to me. My finger twitched on the trigger.

I was in bad shape, very bad shape. From the steroids. It had all come down from the steroids, the crap I'd taken to get big and strong and aggressive so I could play this game that I love.

I felt as though I were sitting next to my body, watching myself, and yet I was in my body, too. I was trying to get up that final bit of courage to end it all. Every nerve inside me was on fire. My mind was racing. I couldn't get a grip on anything. The anxiety attacks I'd been having for the last five months had become so intense that I couldn't stand them anymore. I'd lost control of everything—it's impossible to describe the horror I felt, the fear, the anxiety over that loss of control.

I could hear my teammates outside my room. They were walking back and forth, listening at the door. They talked in low voices, and they sounded very concerned. Every now and then someone would try opening the door, but I'd locked it.

"Tommy," someone would say quietly. "You O.K.?"

However, the image that's really stuck with me all these years is not Chaikin with a gun beneath his chin, but rather the face of the poor delivery boy who had to endure the narrator's drug-fueled thuggery:

One night in my dorm room, I pulled a shotgun on the pizza delivery boy, threw him down and put the gun in his face. It was loaded and I could have blown the kid all over the floor, but I was just fooling around. It was the kind of thing I thought was funny.

Even as a lad, I thought to myself, "Wait, the delivery boy didn't report that to the cops?" I've been suspicious of the scene every since, but I have to admit that it does seem highly plausible. I wouldn't put it past the Columbia police department to look the other way for the sake of Gamecocks football.

(Image via master illustrator Jeffrey Smith; check out his gallery of sports illustrations here.)

September 14, 2011

Everything's Better with Disco

Invoking khan's prerogative to steal a day for book writing. Because if I don't finish this chapter by week's end, I fear the worst for the family's future over the long winter. Even in Queens, keeping a yurt heated ain't cheap.

September 13, 2011

Fear the Beard

One of the many historical realms I'm trying to bring to life in the next book is that of Oregon's Vietnam-era college scene. And one of that scene's biggest controversies was that involving Fred Milton, an Oregon State University football star who refused his coach's demand that he shave his beard—in the off-season, it's important to note. When Milton's stance led to his dismissal from the team, the school's Black Students Union called for a university-wide boycott until he was reinstated. Yet only a small fraction of Oregon State's 14,000 students heeded this request. And so every single black student on campus—all 47 of them—left school to protest Milton's treatment, causing a tremendous stir.

The controversy caught my eye not only because it seems so archaic by today's permissive fashion standards—imagine if Milton had shown up with this—but also because it highlights a divide that reveals the deep-seated fears of Coach Dee Andros' generation. To him, Milton's refusal to toe the grooming line represented a breakdown in social order on par with the distribution of Trotskyite propaganda to kindergartners—the beard was not just a fashion choice, but a tangible symbol of the next generation's resistance to authority:

The strongest formal opposition to Andros came from the 88-member faculty senate. A newly formed Committee on Minority Affairs said the university could not justify disparaging an "individual student's right to determine what constitutes proper social and cultural values," especially as they pertain to mode of dress and style of hair. Later the faculty "lost its nerve on this one," says Andros. "The way the resolution stood, they were giving the hippies license to walk naked at graduation."

Andros also said the faculty had missed the point. "I'm not just fighting hair on the face," he said. "I'm fighting for a principle of education—the right to run my department. If I thought it would end with a beard or a mustache, I wouldn't be so bullheaded. But if they beat you on one issue, they'll keep right on." He said he also had a duty to the coaching profession, that he couldn't "abandon the concepts of training, discipline, team unity and morale." He spoke of the lessons to be learned in the "willingness" of an individual to subordinate himself to a cause greater than himself. He said this might not sound very democratic but he wasn't trying to run a democracy, he was trying to run an athletic program.

I can't help but think that the Milton-versus-Andros beard spat neatly summarized a lot of the political tumult that was to come over the ensuing decades—I've always thought that the simplest, most honest way to characterize the ongoing ideological divide is as hippies versus squares.

This particular story's resolution was long and painful, with Milton ending up at Utah State and the Coach Andros cowed into rescinding his ban by Oregon State's administration. The silver lining, though, is that Andros and Milton reconciled a few years later, with the coach helping his former star get a gig in the Canadian Football League, a place with a rich history of tolerating fantastic beards.