Tiago Forte's Blog, page 41

December 7, 2018

Interview with Weihaur Lau of Created Living, on Health and Wellbeing for Conscious Leaders

I recently interviewed Weihaur Lau of Created Living, a health and wellness-based coaching program for leaders.

Weihaur’s coaching business focuses on helping leaders bring balance and health to their lives. More specifically, he works with a team of coaches and practitioners to help you understand the coping mechanisms you’ve developed to make it through life, and unravel the behavioral and emotional loops that keep them in place. As these loops lose their power, a more authentic and powerful self emerges.

I completed their 3-month coaching program late last year, and had a profound experience learning how my health, my habits, my thoughts, and my performance are so intertwined. I share more about what I learned through the experience in the recorded conversation below.

To read this story, become a Praxis member.

Praxis

You can choose to support Praxis with a subscription for $10 each month or $100 annually.

Members get access to:

1–3 exclusive articles per month, written or curated by Tiago Forte of Forte Labs

Members-only comments and responses

Early access to new online courses, ebooks, and events

A monthly Town Hall, hosted by Tiago and conducted via live videoconference, which can include open discussions, hands-on tutorials, guest interviews, or online workshops on productivity-related topics

Click here to learn more about what's included in a Praxis membership.

Already a member? Sign in here.

The post Interview with Weihaur Lau of Created Living, on Health and Wellbeing for Conscious Leaders appeared first on Praxis.

December 4, 2018

10 Things I Learned as a VA with Tiago

By Kathryn Tongg

1. Establish the preferred method of communication right away. Everyone has a way they prefer to communicate. Whether this is via phone, text, email or other app such as Slack, determine upfront what your client prefers. This will ensure you’re both on the same page with clear expectations.

2. Be patient in the onboarding process. Give yourself at least 30 days to learn the ins and outs of everything. This can include the client’s personality, the company culture, new software and apps you’re using etc. Don’t be afraid to ask questions during the onboarding process. The first 30 days are all about getting acquainted and building trust.

To read this story, become a Praxis member.

Praxis

You can choose to support Praxis with a subscription for $10 each month or $100 annually.

Members get access to:

1–3 exclusive articles per month, written or curated by Tiago Forte of Forte Labs

Members-only comments and responses

Early access to new online courses, ebooks, and events

A monthly Town Hall, hosted by Tiago and conducted via live videoconference, which can include open discussions, hands-on tutorials, guest interviews, or online workshops on productivity-related topics

Click here to learn more about what's included in a Praxis membership.

Already a member? Sign in here.

The post 10 Things I Learned as a VA with Tiago appeared first on Praxis.

November 28, 2018

Tide Turners: A Workshop on Using Business to Fuel Spiritual Awakening

At the end of July, I participated in a two-day workshop in San Francisco called Tide Turners. This is the story of what I discovered there.

I first met Joe Hudson, the creator and leader of the program, at a Consciousness Hacking meetup dedicated to building products that contribute to self-awareness and sustainability. He led a short conversation at the end of the evening with the few people that stuck around, and I was impressed by his presence and vulnerability.

Joe doesn’t have the typical background of a self-help guru. He is the founder and managing director of One Earth Capital, a boutique venture capital firm that invests in early-stage companies developing “decentralized, game-changing technologies in transformative personal development.” This includes businesses working in executive coaching, sustainable agriculture, and financial services.

As his website explains, his teacher and mentor was Cees De Bruin, a Dutch investor and entrepreneur who had a way of asking questions and getting to the root cause of the challenges that people faced in their lives and businesses. Joe describes his initial fascination at watching how De Bruin combined deep empathy and compassion for people, with an uncanny salesmanship ability:

“One day, I watched Cees, a quirky guy from Amsterdam, talk to an American farmer. He sat and asked questions and at the end of their conversation, the farmer wanted to buy the product that Cees was selling. Cees never tried to convince him into anything. The sale was a natural progression of events that stemmed from their conversation that led the farmer to realize things about himself he hadn’t before. Once the connection was made, the sale was done. This progression fascinated me and I wanted to learn more. Over my time spent with Cees, I saw this gift over and over again.”

His time with De Bruin was part of Joe’s 20-year spiritual odyssey through meditation, Eastern philosophy, neuroscience, psychology, and purpose-driven business. Tide Turners and his other courses are his attempt to integrate and teach what he has learned to leaders and founders doing important work.

Beginning the journey

A few weeks later, a friend told me he had completed the Tide Turners workshop just a few months before. As I waffled and wavered over whether I would take the plunge, he leaned over, looked me straight in the eye, and told me decisively that I needed to do it. He recommended it as the most impactful personal growth experience of his life, and had the results to match. I decided to enroll then and there.

From the very beginning, Tide Turners was unlike any other “self-development program” I’d ever experienced. Typically, workshops are held in corporate-looking office spaces or hotel convention rooms. Our course was held in a beautiful mansion at the edge of Alamo Square in the hills of San Francisco, with modern, clean interior decoration and lots of light.

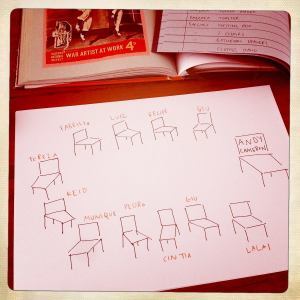

There were no sign-in forms, introductory videos, or seating arrangements. It felt more like going to a dinner party at a friend’s house. About 25 people showed up, and we sat in chairs arranged in a single large circle in the living room of the house. The participants were of different ages and backgrounds, but there was a solid majority of young, Silicon Valley tech workers and founders. What they seemed to have in common as we shared our goals for the weekend was a big vision for something they wanted to create in the world, and a track record of using personal development as a path to get there.

My goals for the workshop, scrawled hastily in my notebook in the minutes before we got started, were simple:

Discover my next area for growth as a leader

Usher in the next stage of evolution of Forte Labs

Found Building a Second Brain as a movement

In other words, my priorities were myself, then my business, then my work. During the weekend I would discover just how many layers there were to these seemingly simple goals.

The official learning objective of the workshop is straightforward and practical:

“Bringing awareness to how our consciousness affects our communication and learning techniques to become more effective in the following areas: fundraising and sales, product development, customer service, attracting great talent, and managing teams.”

But there is a deeper, more intriguing story to Joe’s work. One of the most fundamental assumptions in modern society is: that you can either be spiritual and have inner peace, OR live a successful life with material rewards. But not both.

Joe is seeking to show that the most worldly experiences, such as in business, can fuel profound spiritual awakenings. That what we think of as competing priorities can actually be complements.

Paraphrasing from the Tide Turners website, Joe believes that the experience of oneness with the universe that is the goal of so many spiritual traditions is not an endpoint, but a starting point. From there, we naturally ask how we can work from that place of oneness, start and grow businesses from oneness, have relationships in oneness, create community in oneness, and parent from oneness. His intention is to discover how the journey of self-realization can be one and the same as the journey of living an effective, successful life.

These intentions resonated deeply with me. It is very much the same thing that I am seeking in my work, except not stated so explicitly. As we finished our brief introductions and began the exercises that would take up most of the weekend, I began to sense that I was going to uncover something very profound and powerful in this course. I decided to maintain as open a mind as possible toward what that might be

The basic methodology that Joe teaches is called VIEW, which stands for Vulnerability, Impartiality, Empathy, and Wonder. But like all frameworks, the power is not in the framework, but in how each of these “modes of being” are embodied. The weekend was dedicated to experimenting for ourselves what it meant to stay “within the VIEW”, spread out over two days of conversations, exercises, and activities.

Vulnerability: the courage to question what keeps you separate from others

The first exercise was in pairs, each person sitting in a chair facing their partner knee-to-knee. It was an eye-gazing exercise, designed to break the ice and help us begin letting our guards down. Sitting face-to-face with a stranger, I felt a slight twinge of anxiety as I stared into the eyes of a stranger that I knew was about to see behind the curtains of my well-ordered life.

For the second exercise, they asked one partner to stay silent, while the other verbalized the emotions or impressions that they felt they were receiving as they locked eyes.

In conversation, I usually try to stay fairly impassive and “neutral,” not wanting to react prematurely or give away what I’m thinking. I’ve always thought that this made me a “good listener,” so I was shocked to hear the unfiltered stream of impressions of me from my partner: frustrated, annoyed, angry, bored, judgmental, distracted.

I learned in this exercise that I put a tremendous amount of energy into not “giving anything away,” but that this just makes me come across as withdrawn and uninterested, if not outright hostile. I think I’m being stoic, when in fact I’m being cold. Then when they react negatively to this coldness, my story that people aren’t interested in me or what I’m doing is confirmed. A self-fulfilling prophecy, like all stories.

Through these simple exercises I began to learn what was meant by the V for Vulnerability in the VIEW framework. I had understood vulnerability as something akin to embarrassment, a collapsed definition that I suspect has roots in my conservative Northern Italian (by way of Brazil) upbringing. I had a trick for being vulnerable when I wanted to be – just say something embarrassing – but this was a poor substitute for the real thing, and often backfired for obvious reasons.

On day 1 I learned that vulnerability is more like a growth edge, one that is unique for every person and constantly shifting from moment to moment. A topic or conversation that is vulnerable in one context may not be vulnerable at all in a different context. Your growth edge is whatever is on the edge of comfort for you in a given moment. You can’t identify it using a checklist or algorithm, because by the time you do, the moment will have passed. You can only sense it, like a shifting chasm you are trying to communicate across. And you only have a split second to decide whether to jump, before the moment passes.

For the third exercise, we got into pairs again, this time to trigger each other on purpose. A collective groan of discomfort passed through the room as we were instructed to ask our partner what they least wanted to hear in the world, and then to say it to them to their face: “You’re not good enough”; “You’re not going to make it”; “You are ugly”; “Your business is never going to succeed”; “You’ll always be alone.”

The purpose of this exercise was to begin practicing the core technique of the VIEW framework: How/What questions. On the surface, this is very simple: ask questions of your conversation partner that begin with “How…?” and “What…?” That is, questions that invite open-ended, constructive answers, rather than “Why…?” questions that demand justifications or “Do you…?” questions with yes/no answers.

Instead of “Do you love your partner?” you ask “What would it look like for your relationship to thrive?”

Instead of “Why do you want to quit your job?” you ask “How could your job satisfy all your needs?”

Instead of “Which one do you care about more?” you ask “How could you have both?”

The purpose of asking questions in the first place is to help your partner access their innate curiosity and intelligence in resolving their own problems. Instead of giving advice or proposing solutions, which always encounters resistance, you invite them to tell the truth to themselves about the situation they’re facing. Once they’re able to do so in a spirit of generosity and self-love, the path forward becomes easily illuminated. And they’re able to walk it because the answer came from themselves, and strengthened their own agency, instead of arriving from an external source.

I learned another lesson about vulnerability through this exercise: it takes real vulnerability to ask the question that pierces the heart of the matter. They might react badly. They might think you’re being nosy or insensitive. They could very well tell you something that is hard to handle. But this vulnerability is essential to the art of asking questions. Unless you’re in the whirlpool with them, feeling the same fear and uncertainty, asking questions amounts to nothing more than an interrogation. Only a question asked with vulnerability can evoke a vulnerable answer.

Impartiality: taking as a starting point that the person in front of you is already perfect in every way

The second element in the VIEW is I for Impartiality.

Instead of leading the conversation to a predetermined outcome of your own choosing, you hold no preference for where it ends up. Instead of being attached to a goal, outcome, breakthrough, or resolution for this person and their problem, you allow them to lead the conversation where it needs to go.

When we talk with people who are dealing with challenging circumstances, we often think we know what’s right for them: take this course, try this product, implement this method, choose this option. We’re uncomfortable just being with their pain. We’re scared to hear what it’s really like for them, and to have to carry that weight. So we hear one thing that kind of reminds us of one thing that worked that one time and…poof, we offer some advice.

But the arrogance of believing that we know what’s right for someone after 15 minutes of conversation is staggering. Impartiality invites you to consider that they are the genius of their own life. They know what’s best for them – the best you can hope for is to reflect some of that wisdom back to them, providing access to the truths they already know.

This guidance was, of course, the hardest one for me to truly swallow. Joe sat next to me in my partner conversations, calling out “partial!” every time I asked a question that was stealthily leading my partner in a certain direction.

Me: “How do you think it makes people feel when you do that?”

Joe: “Partial”

Me: “How do you feel when that happens?”

Me: “Why do you want to sell your business?”

Joe: “Partial”

Me: “What benefits do you think selling your business will bring you?”

Me: “Do you value integrity?”

Joe: “Partial!”

Me: “How could you have integrity in this situation?”

It took quite some time for me to wrap my head around what true impartiality looks like. It represents a radical level of open-mindedness, an open-ended exploration leaving all my own opinions and judgments aside. It is so difficult, when hearing about a problem that I am certain I know how to solve, to instead ask “What benefit would that bring you?” or “How do you see that action relating to the situation you’re facing?”

But the more I do it, the more I am shocked by how different other people’s thinking is from my own. The more I hear about what motivates or interests others about a given path of action, the less I recommend my own solutions. I’ve come to understand that the answers I’ve found only apply to a narrow slice of life, for a narrow slice of the population.

Joe explained that, when we are afraid and our amygdala is engaged, we tend to look at things as black or white. Our only options seem to lie at the extremes: break up or stay together; sell the business or keep it; take the job or don’t; move to a new city or stay put. But this is rarely the best way to look at things, because it conceals a vast spectrum of options in between. There are always degrees of freedom, hidden alternatives, and subtle options available. But it is difficult to even see them when acting from a place of panic and fear.

The fear of being alone

It was toward the end of day 1 that I had my first major breakthrough. As usual, it came from the most unexpected direction.

Skirting the edges of my comfort zone, I came face to face with the fear of being alone. The first few years of my business had been some of the loneliest of my life, toiling for week after week on my computer trying to make something happen, trying to keep my momentum and my spirits high. I’ve thankfully moved on from that time, but had never realized that that experience had left a wound. I had decided at some point that I was never going to experience that kind of loneliness ever again.

Fast forward to 2018, and it would seem that my current situation couldn’t be further from loneliness. I am working with 7 close collaborators on a range of interesting projects. I have a support team of contractors supporting me with bookkeeping, tax preparation, legal services, and marketing. I have a strong network of customers and advocates constantly telling me how much they appreciate me and my work.

But the numbers tell a different story. After peaking in February with the relaunch of my online course, revenue had been falling month after month. Expenses rose steadily as I hired more people on more projects. I spent money as fast as I could to “buy growth,” yet found that none of our offerings scaled as quickly as we needed to cover expenses.

I began to tell the truth to myself on day 1 of Tide Turners: that I was so afraid of being alone again, that I was making business decisions with the goal of keeping people around. But I didn’t know how to manage so many people, or make a business of that size profitable. The only thing I knew how to do was hunker down and produce things. So I ignored the emails and phone calls from my team asking for direction, and instead powered through a string of solo achievements, trying to show that I was making something happen.

The irony is that this whole situation gave me the very isolation I was so desperate to avoid in the first place. I was sacrificing my business to create a sense of belonging. Yet without a business, there was no team to belong to.

Empathy: allowing their experience in, without falling into it

On day 2 we began exploring E for Empathy. It was like wading through a soup of existing preconceptions and associations with this most overused word.

For the fourth exercise, we began exploring our relationship to the voice in our own heads. It turns out that this is where empathy has to begin – with ourselves. It is impossible to have real empathy for others unless we first have empathy for ourselves.

Each partner was instructed to vocalize their inner dialogue out loud to their partner, unleashing the torrent of doubts, worries, fears, speculations, and musings we usually keep to ourselves. This part was easy.

The second part of the exercise was harder: we had to turn on a dime and tell our partner our gifts. It was like a locomotive screeching to a halt, the judgmental mind suddenly reversing course to become an appreciative mind. I noticed how much more difficult it was to see the good in myself, to look inside and find something to praise. I’m always on the lookout for a problem to solve, and will find one on the inside if I need to.

We began to ask ourselves, “What evidence do we have that the voice in our heads helps us?” It’s an intriguing question considering how much we revere the advice it gives us. The voice is so often speaking from the neediest, most fearful, most lonely parts of us. As Joe says, “The voice in your head is the unloved bits of previous generations.”

Throughout the weekend, Joe conducted “interviews” to help us better understand each letter in the VIEW framework. He would sit face to face with a participant, as the rest of the group sat on the floor and observed. He demonstrated the How/What question-asking, keeping his interviewee in “the VIEW” of vulnerability, impartiality, empathy, and wonder.

The most fascinating thing was that each person’s situation was completely different, yet the same process of asking questions always managed to lead them to a place of authenticity and healing.

One particular interview showed us the tremendous power of curious questions.

A woman recalled the memories of a traumatic early experience that had led her to a series of disappointing romantic relationships, in which she couldn’t bring herself to open up to her partner. Within 10 minutes of gentle, curious questions, Joe was holding two thick cushions in front of him, and she was taking out her bottled rage in a ferocious barrage of kicks, punches, and screams. When she was finally spent, she sat down with a satisfied “thank you.”

Joe explained why having access to all one’s emotions is so critical: “Joy is the matriarch of all emotions – she won’t enter a house where her children are not welcome.” In other words, if you cut off access to any emotion – fear, disappointment, love, anger – you also lose joy in the process.

This is most evident when it comes to anger, the most taboo of all emotions in modern society. We learn ways of shutting down our anger at a very young age, because the consequences for letting it out are so severe. But anger, Joe told us, is a form of surrender. Without it, all our other emotions are throttled.

Anger is like a hose running through us from top to bottom. If it gets kinked one way, we get an explosive temper. If it’s kinked another way, we get passive aggression. But if it becomes unkinked, you get pure determination, the kind that Martin Luther King Jr. and Gandhi had.

Wonder: leaving the door open to the possibility that anything could happen

As we began the interviews ourselves, my newly trained partner began asking me a series of questions about my work and my life, for example:

“What is the biggest barrier to your freedom?”

“How would you frame the problem?”

“What excites you about that prospect?”

“How could you have both?”

“What does success look like for you?”

“What are you afraid might happen?”

“What would life look like if that intention was fulfilled?”

“What hasn’t been working for you?”

“How would you approach that if money wasn’t an issue?”

“What would your business look like if it was thriving?”

And a cascade of insights began: I realized that I felt an immense obligation to fulfill my potential. As a heavy burden, not an inspiring journey. I felt that I had to repay an enormous debt that I felt I owed everyone who had ever invested in me.

I broke down in tears as I thought about generations of my ancestors, who had sacrificed and struggled so that I could have a better life. I thought of my parents and grandparents, who had spent so many years teaching me everything they knew. I thought of the countless teachers, coaches, mentors, managers, friends, and romantic partners it had taken to make me the person I am today.

I had never realized what a crushing burden I felt at the impossibility of ever paying back the love and care that all these people had given me. My source of motivation for many years had been the desire to pay off the debts of my privilege. That fuel had served me well, but I saw that it had finally exhausted itself. I had exhausted myself. I was done with the endless task of proving that I was good enough, capable enough, successful enough to deserve what I had been given.

As I talked through these realizations with the group, Joe looked at me and asked, “What is a different interpretation for all that?” I responded almost instantly: “That they chose to sacrifice because they loved me, and all they ever wanted was for me to be free.” I didn’t need to pay anything back. I didn’t need to prove that I deserved the privilege I had. It is a privilege to do meaningful work that has a positive impact on people’s lives. But I have the privilege of doing that work out of gratitude and joy, not out of obligation.

As the burden of obligation lifted from my shoulders, I had a ground shaking breakthrough: I had no desire to build a large business. This thought stopped me dead in my tracks. It was the unthinkable thought I hadn’t allowed myself to consider.

I had been working for years with the unstated assumption that I had to build the biggest possible business as fast as possible. I leapt at every opportunity to grow or gain exposure, even if it made me miserable. I spent lavishly on anything that would help me go bigger or move faster. I took on projects or clients out of obligation, as if I had no choice in the matter. Perhaps influenced by the tech startups I was surrounded with in Silicon Valley, I thought hypergrowth was the only path forward.

The outcome was that I had an unprofitable company bleeding cash, a team of contractors I didn’t know how to put to use effectively, a range of projects and responsibilities I had no desire to pursue, and no time left over for the open-ended thinking and writing I loved so much. Pushing hard against what reality was trying to tell me, I found reality pushed back even harder.

When I really got to the bottom of what I wanted, digging down beneath layers of “shoulds” and “ought tos,” I found that what I really desired were very simple things: more time with my family, a small circle of smart friends and collaborators, time to think and travel and explore new things, interesting projects that made a real difference, health and peace of mind. I’d placed all these things on the far side of building a massive company, telling myself I couldn’t indulge until I’d done it. But what my partner’s questions revealed is that they had always been there for the taking.

Wonder is the final element in the VIEW framework, and the most mysterious. It asks us to question whether we know where all this is going. It asks us to stand in awe of the complexity and ineffability of the human experience. It has the questioner not try to find a problem and solve it, but to always remain curious as to how the human being in front of them works, and why.

Remaining within the VIEW is really just a checklist for unconditional love. You can cycle through each element as you are asking questions, asking yourself which one is missing, which one you’re withholding. Vulnerability asks you to constantly turn toward what you’re protecting, what keeps you separated, and have the courage to question it. Impartiality has you take as a starting point that the person in front of you is already perfect in every way. Empathy has you allow their experience in, without falling into it. And Wonder leaves the door open to the possibility that many things can happen not covered in any framework or checklist.

Aftermath

On Sunday evening we walked back out into the world, charged with the homework of using our new question-asking powers and VIEW framework to produce new connection and intimacy in the relationships that matter most to us.

It’s easy to undergo a unique experience like this one, and to walk right back into the same patterns and habits that had you dissatisfied in the first place. It is the practice that makes the difference. New practices take practice.

I’ve waited a few months since completing the Tide Turners workshop before writing this account. I wanted to see if I would be able to put these breakthroughs to use in the “real world.” I’ve found that they are incredibly effective in a wide range of situations. I’ve used the tools I learned there to help a friend see that his career was a completely wrong fit for him, and to begin the transition to something else. I’ve used them in my coaching, helping my clients to see the deeper layers of narratives driving their “bad” habits (and even questioning the labels of “good” and “bad” that keep those habits locked in place). I’ve used it with my family members, facilitating incredible breakthroughs in their relationships and careers. And I’ve used it on myself, bringing curiosity to situations that before I would have felt only self-criticism.

The VIEW and How/What questions have been among the simplest and most effective tools I’ve encountered. I believe that Tide Turners is part of a new generation of personal development programs, adapting to modern ways of communicating and relating while also addressing some of the traditional pitfalls of the self-help industry.

The self-help industry often treats the mind and body as enemies to be beaten into submission. Instead of adding yet another strategy or technique, burying your true self under yet another layer of obligation, it focuses instead on unwinding the negative patterns that keep us from accepting and loving ourselves.

Joe said something that has really stuck with me, and that I’m only just beginning to understand: that you have to allow your heart to break a little to increase your capacity to love. I interpret this to mean that it is only when we expose our hearts enough to allow them to be broken, that we have a chance to expand our heart’s capacity. And it is our heart’s capacity, not our intellectual capacity, that is the bottleneck to the change we want to see in ourselves and the world.

I went into the workshop seeking to grow my self, my business, and my work. For myself, I discovered that my growth edge is my heart – connecting to my desires, my dreams, my emotions, and my body and aligning all of them with what I do every day.

For my business, the growth edge is fundamentals. Profitability, financial solvency, systems and routines needed to even out fluctuations in revenue and help me make better decisions. I’m using You Need a Budget to start budgeting seriously, and Profit First to bring my business finances under control.

And for my work, I think the growth edge is to give it away. I’ve been at the center of everything, the source of everything for long enough. In writing the Building a Second Brain book, my intention is to write simply and clearly enough that anyone can benefit from it. This is some of the hardest writing, to separate my ego and my opinions from the essence of methods that just work. It is only by surrendering control of what these ideas could become that they have a chance of growing beyond my reach.

There are no more Tide Turners workshops scheduled for this year, but you can sign up for their newsletter at the bottom of this page to receive updates on future courses. You can also follow Joe on his Facebook page, where he posts short videos. I’ll leave you with the testimonial video I made on the final day about my experience:

Thanks to Daniel Thomason, Vita Benes, and Massimo Curatella for their comments and feedback.

Subscribe to Praxis, our members-only blog exploring the future of productivity, for just $10/month. Or follow us for free content via Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, or YouTube.

The post Tide Turners: A Workshop on Using Business to Fuel Spiritual Awakening appeared first on Praxis.

MESA Part 5: The Future of Work That MESA Envisions

MESA Co. considers their method not just a problem-solving tool, but an entirely new way of working. As their ambitions have grown, they’ve begun looking toward a future in which this way of conducting work is nothing more than common sense.

In this article, I’ll outline a vision for what the future of work might look like if MESA has its way.

The era of the briefing is over

Central to the work of so many creative agencies and consulting firms is “the brief.” It is the starting point of every gig. The bible that guides the project to completion. But MESA believes that the era of briefs is over, for several reasons

First, because the assumption underlying briefs has become outdated: that a problem can be fully communicated in a written document. In fact, there is no way for the problem owner to ever convey everything they know. They don’t even know everything they know. So how can you?

Second, because briefs are a formal, bureaucratic process designed to satisfy the needs of administrators, not doers. No one ever writes “I don’t know” in a brief. They fill in some kind of answer, or more commonly, omit that section altogether. It is much easier, on the other hand, to say “I don’t know” in a group setting. This “not knowing” is the opening a maker needs to start exploring. Filling out forms only postpones the learning.

And third, because briefs do not get people excited to work on a project. Especially when working across silos or companies, it is critical to get everyone excited and eager to jump in. Handing them a long, dry document is just about the worst way to do so. MESA doesn’t allow clients to give participants a brief at any point. It would defeat the very energy they are trying to create.

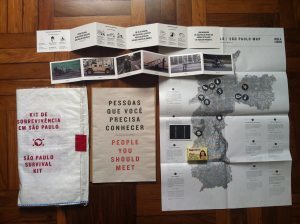

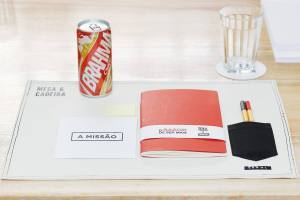

What will replace the venerable brief? A mission. But it’s not enough to just change what you call it. A mission brings with it a certain context. Missions are completed by small, dedicated teams focusing completely on an objective. Missions strive for important and strategic outcomes under uncertain circumstances. There is an element of risk in completing a mission.

The future of work that MESA envisions is one in which boring briefs are replaced by challenging, but meaningful missions targeting the world’s most pressing issues.

We believe in doing

One of MESA’s favorite slogans is “We believe in doing.” The subtext continues, “…rather than debating.” This imperative runs deep in their culture – that it is doing that produces progress, not talking.

Their standard of success is not any of the typical ones used by most agencies or consultants: meeting the deadline, on-time and on-budget performance, customer satisfaction, or complying with the letter of the brief. A successful MESA is one in which the prototype becomes real.

It is a punishing standard, since so much of what makes a prototype into a real product is outside MESA’s control. No agency would touch such a metric with a ten-foot pole. But it is essential to MESA’s outlook on what they are working for: something real in the hands of real people, not a prototype on a shelf. Large companies now have the talent to do the hard thinking. What they hire MESA for is to help them take the next step into action.

Founder and CEO Bárbara explains that, without holding themselves to such a standard, it would be too easy to fall back into the “workshop world.” She recounts that out of 140 MESAs, there are only 7 that didn’t produce a successful prototype. She counts these as failures, even though the client got value from the experience.

The future of work that MESA envisions is one in which consultants, contractors, agencies, and even employees take responsibility for the ultimate results of their work, instead of just fulfilling their own narrow duties.

Social responsibility will be part of every product

Looking at MESA Co’s client list sometimes inspires a raised eyebrow – they work frequently with companies like Coca-Cola, Dow Agro, Nestle, and McDonald’s that have been criticized in an era of corporate responsibility.

MESA Co’s mindset is one of positive engagement. By working closely with these companies, they have found that they are able to shift how the company thinks about their impact on the world. When first formulating the mission and inviting external participants, it quickly becomes clear that the product has to have a connection to a worthy cause or important problem. Otherwise, experts and makers just won’t be interested in helping. The MESA process reveals that making socially responsible products is not just a marketing strategy anymore. It is essential for attracting the best talent.

This is a different approach to corporate responsibility. Instead of shaming or isolating companies and their products, they are invited to excel and to innovate beyond the constraints that currently lead them into questionable behavior. This makes them the source and the owner of their corporate responsibility, instead of just minimally complying.

The future of work that MESA envisions is one in which companies do good while doing well, not because it looks good, but because it delivers the best possible results.

The conviction of the maker

We are living in the midst of the “Maker Movement.” Around the globe, garage hobbyists and weekend warriors are making software, hardware, and content for side income, for fun and learning, or to solve a problem in their community

But in the future, everyone will need to have the attitude of a maker. They’ll need to know how to make things of high quality, even if that’s just a webpage, a text document, or a well-crafted email. They will need to have ownership over what they make, advocating for it in their organizations. They will need a spirit of curiosity and constant learning, to stay abreast of the changes rocking every profession and industry.

As Bárbara Soalheiro says, “Part of what we do is trying to understand how things are made. And that breaks this idea that there is a certain path that you have to follow. Participants get a better understanding that it can be easier than they thought, more in their hands than they thought. They get a better understanding that everything there is has been created. And if everything there is, is created, then I can create something that is completely new. Or that someone hasn’t told me to do before.”

Makers know how things work, or they know how to figure it out. They know that anything can be hacked. They understand that anything can be modified, enhanced, or adapted if you open the cover and tweak things. This “hacker” mindset is often totally foreign to people working in large companies, who are used to relying on a process for everything they need. Working with the MESA Co. staff and external experts and makers, they quickly learn that there is no prescribed path you have to follow to make most things. If you leave out what isn’t essential, you can often create a prototype in a matter of hours that gives you most of the learnings of the full-fledged version.

Working on concrete, functional prototypes has a final benefit: it is very clear what everyone needs to do after the MESA ends. There is a jerry-rigged but coherent thing sitting on someone’s desk, not just a pile of “takeaways” to decipher. In some cases, this prototype can be taken directly into production, instead of spending months in deliberations.

The future of work that MESA envisions is one in which people work out of personal conviction, not obligation. This conviction comes from personal involvement in the nitty gritty details, and seeing how every detail determines the final impact on someone with a need.

The power of feminine leadership

It’s hard to ignore that MESA is a company founded and led almost exclusively by women. Although this was not an explicit intention, it also wasn’t an accident.

Bárbara explains the connection to MESA’s founding metaphor: “A MESA is always better when it closely resembles one of those long lunches, where you enjoy yourself, but also have a conversation and argue. There’s something powerful in receiving someone well, in taking care of whoever shows up. And that seems very feminine to me.

One of the key roles in every MESA is “Experience Leader.” This person takes care of every little detail, from the place settings to the interior decoration to the food. The job of the Experience Leader is to make sure that everyone feels comfortable and at home. And this role has always been filled by a woman.

Contrasting feminine leadership with the masculine version that is so often the default, Bárbara says, “I think men really feel a pressure to be at the center of attention…Women tend to be more comfortable with the number 2 position. And there’s something very cool about that, in being okay with doing good work alongside someone you consider incredible…It would be a problem if everyone had to always be #1.”

For MESA Co., feminine leadership is about realizing that the more people shine, the better the MESA will be. It is about realizing that it doesn’t take away your power to give power to others. Power is multiplicative – the more you give away, the more you have. The MESA experience naturally tends to loosen the grip that people have on protecting their egos.

As Bárbara puts it, “It is about involving them in the situation that we all need to do this, we only have a couple of days, so you don’t really have time to bullshit, to be very ego-centric. It was very interesting when we started working with companies, bringing decisionmakers like presidents, owners of companies to the table, how the format didn’t allow them the space for their egos…That causes people to finally understand what collaboration is about. It is not about being nice, it is not about doing good to the world, it is about finding the perfect match between your self-motivation and a collective, shared motivation.”

The future of work that MESA envisions is one in which the viewpoints and the opinions of a talented group of professionals can become subsumed into a collective mission. Not against their will, and not forever, but occasionally, in service of a mission that is greater than any single person.

Transformation

The MESA Co. team doesn’t often talk about it, but there is a transformation that happens in the week, sometimes and for some people.

Creative, talented people, sequestered in a room and pushed to the edge of their capabilities, find themselves amazed at how much can be accomplished in how little time. For the first time, they see something through from beginning to end, and show it to the world as their own creation.

Bárbara describes this epiphany: “It is the same feeling you get from when you bake a cake for the first time. The cake wasn’t there. You just have flour, eggs, and sugar. And then you take it out of the oven and then it’s a cake. If you have ever baked a cake, you know that feeling. It is really powerful.”

The transformation is conceiving of oneself as a creator. As the source of everything that could be. The future of work that MESA envisions is a future of our own creation.

Subscribe to Praxis, our members-only blog exploring the future of productivity, for just $10/month. Or follow us for free content via Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, or YouTube.

The post MESA Part 5: The Future of Work That MESA Envisions appeared first on Praxis.

November 27, 2018

The Ecommerce Influence Podcast: Why You Should Stop Organizing And Build A Second Brain

I recently recorded an interview with Austin Brawner and Andrew Foxwell of Ecommerce Influencers, in which we talked about how capturing and saving knowledge can enhance everything from employee onboarding to marketing to gaining perspective on life.

Listen below or click here for show notes and a full transcript:

Subscribe to Praxis, our members-only blog exploring the future of productivity, for just $10/month. Or follow us for free content via Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, or YouTube.

The post The Ecommerce Influence Podcast: Why You Should Stop Organizing And Build A Second Brain appeared first on Praxis.

MESA Part 4: The Origins of MESA

The MESA Method is full of firmly held beliefs and sharp distinctions. To understand why they’re so important, you have to understand where they came from. I recently sat down with Bárbara Soalheiro, the founder and CEO of MESA Co., and Lígia Giatti, her number 2, to try and understand the origins of this new way of working.

The journalistic instinct

Bárbara traces the beginnings of MESA all the way back to her first job. After graduating from college, she entered the New Talents program at Editora Abril, the biggest publishing house in Latin America. She worked on a magazine called Superinteressante (meaning “Superinteresting”), which involved diving deep into topics such as mental health or prostitution or alternative medicine for 3 to 4 months at a time, before turning it into a feature piece.

This was the beginning of her fascination with immersive deep dives into interesting topics.

By the time she was 26, Bárbara became the youngest ever editor-in-chief at Editora Abril. She was charged with a major restructuring of the teen brand Capricho, which included a magazine, a website, a range of licensed products, and events. Her approach was a radical change from the magazine’s past: to treat young girls and their concerns as legitimate and worthy of attention, instead of as trivial and silly.

In 2006 they launched a new edition, and the only story related to beauty was a serious inquiry into why frizzy hair was automatically assumed to be bad. Bárbara recalls thinking hard about why the magazine had been such an important part of her teenage years. She realized that it was the one place that took her concerns seriously. She remarks, “Hair is actually the most important problem in the life of a 13-year old girl!”

Working at these magazines formed the foundation of Bárbara’s career and professional outlook. Her experience as a journalist taught her how to seek out the best person to help her answer a question or solve a problem. It gave her experience in creating products targeted to a very specific audience. And critically, to deliver those tangible products on a regular basis.

Learning by doing

In 2008, Bárbara was invited to work at Fabrica, the communications research center for the Italian clothing brand Benetton in Treviso. There Bárbarta became editor-in-chief of Colors, a magazine founded in 1991 by photographer Oliviero Toscani and art director Tibor Kalman to “show the world to the world.” The magazine looks at social issues around the world through the lens of first-person interviews and attention-grabbing photography.

Colors gave Bárbara’s her first in-depth experience with technology. She worked on the digital transformation of the magazine, turning their website into an early collaborative platform and launching one of the first ever augmented reality issues in the world.

Working on these projects, Bárbara fell in love with an open-ended, improvisational style of working that favored learning by doing. She says: “At Fabrica, this really unique place which I’m really in love with, I had the happiest two years of my life. It was working in an environment that was super chaotic, dramatic and intense. There were no rules. There isn’t a really clear idea why you are there. Some people hate it. It made some people leave because they couldn’t function in an environment like that. But it gave me the opportunity to just do whatever I wanted. And by doing whatever I wanted, to learn how to do it.”

Entering the world of advertising

Returning to Brazil in 2010, Bárbara took on the role of Creative Director at Cubocc, a digital ad agency in São Paulo. She found the transition from journalism to advertising jarring: “Advertising in an agency is a completely different thing and it didn’t make much sense to me, a journalist. One thing I really didn’t get was why I had to solve a problem for Google without people from Google. I used to think: no one knows more about this than my client, why can’t I sit with him and work? It seemed not very smart to me.”

It was during her brief tenure at Cubocc that the idea of MESA was born. She used as her starting point the atmosphere she wanted to create – home-cooked dinners with family and friends seated around a table. She recalls: “It is really important to me, this idea of sharing the same table. So MESA is born from that: sharing the same table, and picking carefully the people who are sitting around this table. And we will make sure that in every group there are all these skills we need to deliver that specific project. And, we make sure that the people come from as different backgrounds as possible. That automatically makes the experience really interesting for everyone.”

In a 74-page Google Doc called “The school,” Bárbara poured out her core beliefs about the best way to work in creative fields, which had emerged from her experience as a journalist, researcher, editor-in-chief, and creative director:

It’s no use waiting for certainty

People want one more study or one more survey to confirm that they are going the right direction. But nothing is 100% certain today. Everything is changing rapidly, and we need to learn to take action anyway.

Making decisions is essential

Decisive decisions carry a team forward. But it takes courage to make a decision when you’re not certain it’s the right one. But if you can’t operate from this place of vulnerability, you’re going to feel ever more vulnerable in this world.

Listen before talking

Thinking you already know the answer is one of the greatest impediments to learning. The best results come from those who are the most open to new ideas.

The problem is always about the whole business

Large organizations tend to treat problems as isolated to one specific division or area. But the greatest problems touch every part of a business. Sometimes the solution can be found in marketing, but sometimes you have to change the product, or make a change in the logistics. Every problem should be treated holistically.

You MUST work with the problem owner

It doesn’t work to “outsource” problems to someone else. The person who is closest to the problem and owns it must be deeply involved in the creation of the solution. If the problem owner can’t participate, there is no MESA.

To work is to create

To work is to create things, which is one of the most fundamental human needs. As such, work should be treated with a certain respect. But often it becomes so procedural and so rote, that people lose touch with the final product or impact it will have.

Independent MESAs

Using these beliefs as a foundation, the first MESAs were “independent,” in that they weren’t delivered for a corporate client. Bárbara viewed the experience initially as a form of professional education, teaching real-world skills through doing, rather than theory.

She started by inviting well-known professionals to “take the head of the table,” including people like Perry Chen, the founder of Kickstarter; advertising expert and serial entrepreneur Cindy Gallop; and “human cyborg” Neil Harbisson. Together they chose a mission that connected to or advanced the work of these headliner names, which is what drew them. Participants paid for the chance to work up close with these thought leaders.

Bárbara explains her thinking: “The first idea was that when you hear someone speak – in a TED conference, for example – you get very inspired. But it’s only when you work with that person – see how he/she makes decisions, how they solved unexpected problems, where they invest energy and where they don’t – that you really learn from them. And when you are a professional with 5 or 10 years experience what you need isn’t inspiration, but this kind of learning.”

MESA started out as a “school for professionals,” where a team of participants would pay to work with someone known for their creativity, experience, or unique perspective. Unlike any other form of professional learning, the team had to deliver something tangible at the end of 5 or 6 days. Bárbara tested this educational format with 7 MESAs over 16 months, slowly working up the courage and the credibility to pitch it to a paying client.

In 2013, MESA Co. began running MESAs for paying corporate clients. Bárbara hired her first co-leader, Lígia Giatti, who is now her right-hand woman and head of U.S. operations. Together they’ve delivered 140 MESAs for more than 30 clients in 8 countries, for companies like Google, Fiat, Samsung, Nestle, and Coca-Cola.

Never use the word “collaboration”

Over this period of testing and refining the MESA method, new beliefs and principles slowly came to the surface.

During the preparation for one early MESA, Bárbara overheard a member of their small team inviting an external participant to “take part in a collaborative process.” A lightning bolt shot through her – she knew it was wrong, but couldn’t immediately explain why.

The reason soon became clear, and has become one of MESA’s core beliefs: to never use the word “collaboration,” because it invites people to work without responsibility. In the experience of MESA Co., using that word creates an environment where no one is responsible for anything in particular. People will “collaborate” to produce a mediocre, middle-of-the-road solution, which usually isn’t one they are truly proud of.

Bárbara cites as an example working with Fernando Meirelles, the respected Brazilian director of such films as City of God. She needed him to show up at the table as nothing less than “someone who knows how to tell stories with moving pictures that reach millions of people.” He needed to own and to advance that responsibility with all his enthusiasm and energy. Bárbara explains, “If you give someone a territory, they will hold that territory and you will have excellent results.”

It is this belief that inspires many aspects of the “MESA experience.” Invitations are made not to “participate,” but to take direct ownership of a specific ”pillar of knowledge.” Each pillar is essential to the fulfillment of the mission, and unique to that person’s expertise. Even the venue and the place settings are designed to impart a sense of gravity and importance. Every participant must feel that they are there for a reason.

Bárbara explains, “We want the best each person has to offer – when the leader uses the word collaboration, it blocks them from understanding why they need each person…This will make it more likely that you’ll have people you don’t need.”

Results over process

Other core beliefs developed in response to what MESA calls the “Workshop World.” These are default attitudes that have taken root among facilitators over the years, and have become ingrained and unquestioned.

In one early MESA that did not fulfill its mission, Bárbara noticed that the Leader had told participants repeatedly to “trust the process.” She realized that this had caused them to lose focus on the final result, to proceed blindly in the face of evidence that no progress was being made.

She tells people today to NOT trust the process. She explains that “When you emphasize the process, you get something in the middle ground, and the middle ground is never excellent.” The focus should instead be on the final result, and whatever it takes to produce it.

Bárbara cites the example of a MESA in which the participants were 11 year-olds. The initial idea was to have them create a collaborative art project, which would become the homepage of the client company. But then they realized that most kids aren’t good at drawing. They had to make a decision: trust the process and put up with whatever it produces, or change the process in order to produce the best possible results?

They chose the results, and adapted the MESA process to produce it. A professional illustrator was hired to turn the best of the drawings into a homepage that met a high standard of excellence. Although there was some disappointment on the part of the kids, in the end everyone could be proud of the solution they contributed to, even if indirectly.

Lígia explains it this way: “Trusting the process has people think more about the process they’ll be participating in, and less about the result.” And a MESA Leader is focused above all else on the result.

The bigger the challenge, the better the MESA

In more recent years, a few lingering questions about when and where the MESA Method applies have been resolved through experience.

For example, “How big of a challenge can a MESA be used for?” After numerous experiments with a wide range of clients, MESA Co. have concluded that it isn’t the size of the challenge that determines the feasibility. Because the most talented people are driven by the greatest challenges, in Bárbara’s words, “The more difficult the challenge we get, the better the MESA is.”

What does need to be calibrated is the mission and the prototype. The Leader and her team needs to determine what the team can make in a 5-7 day timeframe that will help unlock the problem. This is a question of experience and judgment, to thread the needle between feasibility and ambition.

Bárbara cites a MESA with the Italian automaker Fiat as an example. The problem was, “How can you create a connected car when everyone has a better system in their pocket?” She knew that everyone who had anything to do with cars was thinking hard about this problem. It is an enormous challenge, and MESA Co. had to think of a prototype that would meaningfully advance a solution in just a week.

Following her instincts as a journalist, Bárbara reached for the most talented person she could find: a well-known and respected car designer working in Tokyo on one of the world’s biggest brands. He had never heard of MESA and didn’t know what to expect, but the pitch was irresistible: to fly to Brazil for a week to work directly with the decision makers at Fiat, along with 15 people with all the relevant skills and knowledge he would need.

They knew they couldn’t prototype a car in 5 days, but they could prototype an online store selling connected car accessories. Such a storefront could be created in hours, and would allow for enough learning to forge a path forward for the company.

Anyone can take part in a MESA

Another lingering question was, “Who can participate in and benefit from a MESA?” Internally, the team used the example of a dentist as someone who probably wouldn’t work very well in such a free-form environment.

That is, until they actually had a dentist take part in one. The “cyborg artist and transpecies activist” Neil Harbisson led an independent MESA, and chose as his mission creating a “telepathic tooth” that would allow him to communicate with others subvocally.

They decided that they needed a dentist to advise on the feasibility and health implications of the implant. He turned out to be an enthusiastic and critical contributor, helping develop a hardware prototype that could be tested within one week. Bárbara reports that he had a transformational experience, and has become one of their most ardent supporters.

A new view of diversity

One question I had for Bárbara about the multidisciplinary team that makes up a MESA was, “How do you mitigate the friction between different disciplines?” Working across so many different fields sounds great in theory, but I wanted to know how such a diverse team could work together effectively.

It turns out that it is this very friction that is essential to MESA’s success. Finding themselves in a room of non-specialists, each participant is forced to put aside the jargon, shortcuts, and conventions that are commonly used in their profession, but that can often hide what needs to be revealed. They have to set aside the built-in assumptions of their discipline, introducing what they know in a new way.

One of MESA Co’s most loyal clients is Coca-Cola, and they have done numerous MESAs together. Each and every time, their employees are asked to introduce themselves and their product anew. “But everyone knows what Coke is…” they say, but it is in these re-explanations that new insights are found. Instead of assuming that “everyone knows,” they have to explain it as if no one does.

“Having diversity forces you to go back to the essentials,” Bárbara explains. Each participant begins to see the people around the table as resources, instead of hidebound specialists. This view of diversity is not about keeping up appearances or meeting an artificial quota. It is about producing the best possible results, The MESA team has found again and again that the greater the diversity of the team, the more relevant the solution is to the world. The diversity of the team needs to match the complexity of the challenge.

Five people with the same knowledge and same experience arguing around a table simply do not produce breakthroughs. It is the sixth person, with their new angle and new lens, that can see what no one else can see. This leads Lígia to identify diversity as key to the speed and effectiveness of a MESA: “I don’t believe you can reach the result in 5 days without a diverse group.”

The MESA Method of today is the product of a long journey, including both breakthroughs and breakdowns. It borrows from journalism, advertising, research, branding, and technology to accomplish the seemingly impossible: to “conceive, develop, and prototype something in less than 7 days.”

This requires recruiting the most talented people in the world. As Bárbara describes it, “We look for people who are running some of the most innovative and forward thinking businesses of our time. Real doers who can share their mistakes and learnings and, therefore, accelerate decision-making. We are not talking about a specific pool of professionals that we fish from. We are talking about finding the best person – whoever they are, wherever they are – for that specific challenge. In that sense, MESAs resemble good journalism: go and find who can countbest help you.”

Subscribe to Praxis, our members-only blog exploring the future of productivity, for just $10/month. Or follow us for free content via Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, or YouTube.

The post MESA Part 4: The Origins of MESA appeared first on Praxis.

November 18, 2018

The 60 Inventions that Shaped Information Technology

This is a summary of my tweetstorm on the history of information technology, drawn from the excellent book Glut: Mastering Information Through The Ages by Alex Wright. I mean “information technology” in the broadest possible sense – the methods and tools we use to manage information in all its forms.

1/ This is a tweetstorm of the major milestones & inventions in the history of information technology. From the best book I’ve found on the subject, Glut: Mastering Information Through the Ages by Alex Wright. Affiliate link: amzn.to/2qy1THY

2/ There’s two major dualities that Wright identifies weaving through this history: between hierarchies & networks, each one disrupting and then giving rise to the other; and oral vs written culture, each one setting the stage for innovations in the other

3/ Invention #1: Symbolic thought. Seems to have arisen in humans about 45k years ago, during period of rapid climate change. One theory says that scarce resources required humans to form tighter groups for cooperation & competition. Symbolic thought arose to manage social dynamics

4/ #2: Social networks. Social imitation & exchange allowed humans to manage higher orders of information, by pooling sensory data and allowing individuals to draw on collective experience for survival and problem-solving

5/ #3 Ethnobiographical hierarchies: the basic structure of a family was the earliest template for classifying anything. Anthropologist Cecil Brown studied preliterate cultures and found “universal tendency to divide knowledge of plants/animals into five or six nested categories”

6/ Preliterate cultures also all tend to treat mid-level of hierarchy as the “true name” of something. I.e. a “rose” is more a rose than a “plant.” This psychologically primary category is echoed today as we know plants/animals by their genus, which is in the middle of the hierarchy

7/ #4 Beads and pendants: first symbolic objects adopted by Ice Age peoples. Made of stone, shells, ivory, this “ornamental tech” allowed them to imbue objects with emotion, status, significance, allowing them to forge wider social networks of trust

[image of history of beads]

8/ #5 Bullae (tokens): first written notations, invented in Uruk in ancient Sumer around 5000 BC. Shaped as disks, cones, spheres, tetrahedrons, ovoids, cylinders, triangles, or animal heads, each token represented some form of commercial transaction

[image error]

A bulla (or clay envelope) and its contents on display at the Louvre. Uruk period (4000 BC–3100 BC).

9/ This was first instance of long-running pattern: new forms of information technology first arise for commercial purposes. Writing first emerged as “craft literacy,” later extending to other more creative forms

10/ #6 Writing media (clay tablets, papyrus, engraved bronze/copper): growing volume of transactions required more scalable medium, for government archives, laws, decrees, property records, contracts, treaties, chronicles of battles, etc.

11/ Very beginnings of literature started here, as battles often contained as much fiction as fact. Commercial writing gave rise to astronomy, prophesies, & scientific observations, with first formal writing programs to teach scribes

12/ #7 Document index: oldest index, a tablet with a list of other tablets, found in Ebla, Syria dating to 2300 BC. They don’t seem to be in any discernible order though

[image error]

One of the Ebla tablets

13/ #8 Document abstract: like a proto-catalog, with keywords for previewing the content of tablets, and call numbers to help find them, found in Hittite settlement of Hattusas near modern Ankara

[image error]

Treaty of Kadesh tablet, one of the oldest known international peace treaties between the Hittites and the Egyptians under Ramesses II, in 1259 or 1258 BC. Part of royal cuneiform archives known as the Bogazkoy archives

14/ #9 Bilingual standard: Babylon was first culture to have two languages – one for daily vernacular and another (Sumerian) for exalted written text. Like Medieval Europe (with Latin and vernacular), this allowed early formation of wide scholarly networks beyond local languages

15/ #10 Library: Assyrian King Ashurbanipal formed first library in 7th century BC in Mesopotamia. Confiscated every tablet in every temple and home in the entire kingdom to do it, stamping every one with name of scribe and king

[image error]

Tablet containing part of the Epic of Gilgamesh (Tablet 11 depicting the Deluge), now part of the holdings of the British Museum

16/ This first library established traditions of associating library with worship of deity, following stated acquisition guidelines, & dedicated multi-lingual staff. Earliest libraries were vessels of political power, cementing royal authority & intellectual capital

17/ Other early libraries formed in China in 1400 BC, in Egypt at Thebes in 1225 BC, and India in 1000 BC. They each followed pattern of writing allowing agricultural settlements to become nation states, and then empires, with great flowering of literature

18/ Emperor Shi Huangdi of China burned every book in kingdom in 213 BC, priceless trove of early Confucian and Taoist texts known as the Heavenly Archives (whose most famous curator was Lao Tzu). Planted seed for great ancient Chinese classification system the Seven Epitomes

[image error]

Killing the Scholars and Burning the Books (18th century Chinese painting)

19/ #11 Phonetic writing: reemerging Greek civilization borrowed phonetic script from Phoenicians, with letters signifying sounds instead of ideas. Drastically simplified reading and writing, by using only 24 symbols

[image error]

The Phoenician phonetic alphabet

20/ #12 Theoretic thought: ancient Greeks were first to make the leap from mythic to “theoretic” thought, i.e. ability to reflect on thought process itself. Objectivity allowed them to compare, assess, excavate new layers of text through analysis

21/ #13 Formal biological taxonomy: Aristotle developed fascination with categorization in 4th century BC Athens, proposing comprehensive taxonomy of natural world that distinguished mammals, vertebrates, & introduced binomial naming (genus + species)

22/ Aristotle also introduced metaphysics into classification, distinguishing between matter & form (individual instances vs ideal forms) to claim that all phenomena could be described in terms of substance, quantity, quality, relation, place, time, position, state, action, & passion

23/ Aristotle envisioned what we would call a web of semantic relationships: causality, equivalence, identity, similarity, family, inside of, bigger than, and earlier than. His Great Chain of Being cosmic hierarchy would remain standard for 2k years until modern Linnaean system

[image error]

1579 drawing of the Great Chain of Being from Didacus Valades, Rhetorica Christiana

24/ #14 Universal public library: Great Library at Alexandria, established 300 BC, was first with ambition to classify all world’s knowledge. With 700k items at peak, it was largest library for 1k years afterward

25/ Scholarly environment with wide colonnades, open spaces for strolling and talking. Ptolemy offered big incentives for scholars to study there, including room & board, generous tax-free salary, lifetime employment

[image error]

Artist’s depiction of the Library of Alexandria

26/ #15 Library acquisition backlog: Alexandria library’s acquisition policy was “acquire everything,” and any ship docking at harbor had written works confiscated & added to library. Vast warehouse stored incoming items

27/ #16 Systematic abstraction of meta-data: by Alexandria librarian Zenodotus, rudimentary scheme that assigned books to different rooms by subject. Small tags attached to each scroll described the work’s title, author, and subject

28/ #17 Bibliography: poet and librarian Callimachus was the first to create a separate catalog of the collection, a comprehensive bibliography by author known as the Pinakes. It filled 120 scrolls despite him only finishing 20%

29/ #18 Bicameral collection: Julius Caesar decreed that great library be built just before his death in 44 BC. Statesman Pollio ran with it and built first great Roman public library with support of Catullus, Horace, Virgil

30/ Rome established tradition of dividing library collections into two parts: in this case, Latin and Greek (later, would become Christian and pagan works). Libraries were open to public, had reading rooms, and some allowed private borrowing

[image error]

Artist’s depiction of a Roman library

31/ #19 Salons: Rome established early intellectual salons, where literary, social, political groups could gather to discuss things. Librarians (procurators) had dedicated staff and enjoyed high prestige in society

32/ #20 Books (finally!): 12-foot long papyrus scrolls were unwieldy and had to be read linearly. Codex book, named for attempts to “codify” Roman law, started replacing scrolls. Leafed pages in thick hard covers enabled random access, portability, and durability

[image error]

The Codex Siniaticus is the oldest known complete text of the Bible, from ca. 350 AD. This copy was discovered in 1844 at St. Catherine’s Monastery in the Sinai

33/ #21 Mass production: Roman nobleman Cassiodorus fled siege of Rome and established literary oasis at family estate in Calabria. He established a monastery called a “Vivarium” that would actively produce books, not just archive them

34/ Vivarium became most prolific center of book production in Europe, introducing new faster binding techniques & mechanical lighting to be able to work into the night. These books were duplicated precisely & became canonical texts throughout Christendom

35/ In his work “Foundations of Divine and Secular Literature,” Cassiodorus proposed unified organizational scheme for scriptural AND secular texts, eventually adopted by the Vatican. Actually became precedent for treating secular works on equal footing with religious ones

36/ Cassiodorus also pioneered annotation of texts (marginalia) and specialized, lower-level organizational schemes for specific genres

[image error]

Vivarium from the Bamberg manuscript of the Institutiones

37/ #22 Manuscript templates: Charlemagne secularized scribal trade by forbidding priests from conducting business transactions. He invited renowned scholar from York named Alcuin to establish great imperial library

38/ Alcuin established a central repository for distributing template manuscripts, making them easier to copy and distribute across the growing empire. He also introduced streamlined script, Carolingian minuscule, which our typefaces are a direct descendant of

[image error]

Charlemagne receives Alcuin, 780. Artist: Schnetz, Jean-Victor (1787-1870)

39/ #23 Manuscript preservation: during European dark ages, libraries shifted away from brute accumulation to preservation of knowledge. Reproducing codex books required several skilled workers: skinner, parchment maker, beekeeper (for wax tablets), painter, book binder, & scribe

40/ #24 Private collections: monasteries maintained their own small, idiosyncratic collections, with the armarius in charge of them second only to the abbott in rank. Books were very valuable and kept under lock and key

41/ #25 Scholarly networks: monastic librarians began consulting popular biographical works as guides to growing their collections, which laid foundation for scholarly networks as they coordinated their collections, used similar structures, and borrowed hard-to-find works

42/ #26 Modern catalog: in 1170 first known “scrutinium” emerged, a catalog of monastery’s collection of books. 1495 catalog of the Carthusian cloister Salvatorberg in Erfurt stands as the largest known catalog of the late Middle Ages

43/ #27 Cross-cultural translation & preservation: Muslim world was unlikely haven of written knowledge, since Arabs were oral, tribal culture and Muhammad couldn’t read. But Baghdad had at least 36 libraries, with more than 100 book dealers before falling to Mongols in 1258

44/ In 1004 AD, caliph al-Hakim opened House of Wisdom in Cairo, said to contain 1.6 million books. It was open to the public and books were free to copy, in contrast to jealously guarded European collections

45/ Muslim world preserved a lot of European/Greek thought during Dark Ages: when emperor Justinian closed great school at Athens, 7 prominent teachers went into exile in Persia, which became a repository of Greek philosophy, poetry, science

46/ Arabs conquered Persia and translated these texts. This fueled 500 years of regional dominance and technological progress that made Europe seem like a cultural backwoods

47/ Arabian intellectual heritage seeped back into Europe through southern Italy and Spain, before Mongol invasions left most great Muslim libraries in ashes. This seeded European Renaissance

48/ #28 Illuminated manuscript: transplantation of written culture to warring, feudal, shamanistic tribes of Ireland kicked off by St. Patrick was extraordinarily successful. Irish were first people to be introduced to writing via the book, giving them non-linear way of reading

49/ Ireland became literary R&D center, populated by innovative scribes protected from chaos of dark ages. Within 100 yrs they were producing beautiful manuscripts with provocative illustrations that became gold standard for Europe

50/ Anti-hierarchical, individualistic Celtic ethos infiltrated back to Continental Europe, bringing them lavish illustrations, marginalia, & layered type styles. Irish scribes were proto-multimedia bloggers, fusing words & images in non-linear, colorful, individualistic works

51/ #29 Punch-transfer technique: Medieval Europe saw invention of first semi-mass production of books. Punch-transfer technique “pricked” an overlaying page that served as a kind of stencil. Powder dusted through the holes of the stencil were used by illustrator as a guide

52/ This allowed rise of such secular best-sellers as physiologus (or bestiary), with simple verse descriptions of animals + colorful illustrations. First editions were Biblical but over time became like a proto-encyclopedia, documenting many species and spreading all over Europe

53/ #30 Universities: books began to find audience among emerging bourgeoisie, who were educated at secular universities. Secular book industry began to take shape, with scholars, students, booksellers, professional copyists, and “stationers” fueling book trade

54/ Universities turned out graduates, who sought new types of popular texts written in vernacular: travel journals, poems, romances, lives of saints, and Book of Hours. Christopher Columbus’ travels in the Americas was a best-seller

55/ #31 Paper!: fueled preliminary information explosion, replacing parchment and vellum with pulp-based product. Cost of materials plunged and editions of books became cheaper, driving adoption

56/ #32 Wood block printing: precursor to printing press, allowed reproduction of books at a faster, cheaper pace. Set the stage for Gutenberg

57/ #33 Curators: in Rome, Pope Sixtus IV initiated great expansion of Vatican Library, establishing role of scriptores (curators of the collection). Vatican Library catalog of 1475 provides unique glimpse into evolving organization of knowledge

58/ #34: Printing press: initially enthusiastically embraced by monks, who saw it as more efficient way of spreading the gospel. Wealthy man acted like venture capitalists, funding establishment of new presses as far away as Paris, Lyons, and Seville