R.J. Stowell's Blog: rjsomeone, page 5

July 20, 2021

Pokerface

…by 9:00, a haze of smoke wafting about the piano, Taylor leaned a six-string by the piano. The blonde said, “Sit down, I’ll get the cards.” Dolenz was passed out on the couch. “Mr. Available Light,” said, “I’m outta here.” “Stay. A little bit longer. Come on, Jackson.” The blonde sat in her spot next to Taylor and shuffled the cards. “James, grab a couple beers.” He popped the caps off three Brew 102s, one for the blonde, one for Cass, and one for himself. Stephen and Frey had bourbon neat as the blonde dealt the cards. “Ante up, girls.” Cass was out, Stephen couldn’t keep up, James lit up, held his breath, exhaled, and waved away the smoke. He shook his head and tossed all the wrong cards on the table. “You in, Freybrains?” He took a swig of beer and tossed a chip on the table. He raised his eyebrows. “Come on, Pokerface.” The tension mounted, the blonde took a card, a three for a pair of jacks. She rolled her eyes, threw her cards on the table, and said, “Fleece me with the gamblers’ flocks, I can keep my cool at poker.” She took a swig of beer and said, “But not tonight.” Frey swept the winnings before him. “That’s a pack a smokes.” The blonde did one of her impressions. She said, “You’re good kid, but as long as I’m around you’re second best, and you might as well learn to live with it.” Although Joni Mitchell’s love of painting is an obvious interest, her secret love for the game of poker remains under wraps. Up on Mountainside Drive, poker was a pastime that kept the Laurel Canyon music scene hopping, a tradition that Glenn Frey instigated a few doors down. “I moved to a place at the corner of Ridpath and Kirkwood in Laurel Canyon, and we had poker games every Monday night during football season. [Joni] started coming every Monday night and playing cards with us. They called our house the Kirkwood casino.”Mitchell has never spoken about poker and her secret talent for the card game but has dropped the occasional hint about her expertise in her lyrics. In “Song For Sharon,” Joni sings: “Fleece me with the gamblers’ flocks, I can keep my cool at poker, But I’m a fool when love’s at stake, Because I can’t conceal emotion, What I’m feeling’s always written on my face.”On Taming The Tiger, Mitchell emotionally states: “The moon shed light, On my hopeless plight, As the radio blared so bland, Every disc, a poker chip, Every song just a one night stand.” Under her breath, the blonde sang: “Tiger, tiger burning bright/ Nice, kitty kitty/ Tiger, tiger burning bright/ In the forest of the night” and put her beer bottle in the sink.

Published on July 20, 2021 07:21

July 8, 2021

Cactus Tree - Joni Mitchell

For several years I worked in a mental health facility. My job as a caseworker and therapist exposed me in a clinical way to the female psyche. Out of that, I was able to write one of my first (as yet unpublished) novels, Unblinking. Written from a troubled woman's point of view, many an agent has asked why I was the most qualified writer for the job.

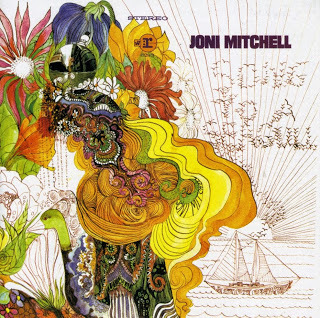

For several years I worked in a mental health facility. My job as a caseworker and therapist exposed me in a clinical way to the female psyche. Out of that, I was able to write one of my first (as yet unpublished) novels, Unblinking. Written from a troubled woman's point of view, many an agent has asked why I was the most qualified writer for the job. Aside from my experience in the mental health field, much of the little I understand of the female psyche I learned from Joni Mitchell. Though Joni's words aren't emblematic of womanhood, her focus is profoundly female. Her debut LP from 1968, Song to a Seagull, illustrates that voice from a youthful perspective, and while Joni would go on to far finer moments, particularly beginning with Ladies of the Canyon, Songs shows a woman of heart and mind with time on her hands, contemplating the world around her. The LP's, last track, "Cactus Tree," exemplifies that perspective in a way that breaks downs my testosterone-laden perspective.

"Cactus Tree" is a catalog of the singer's ex-lovers. She's new to the city, untethered and liberated, exploiting to the fullest the sexual freedom newly available to the fairer sex circa 1968. The imagery is hippie throughout, the schooners and beads and flowers and harbors. Her endless list of lovers brags of hippie promiscuity. For the first three verses, Joni presents her relationship through the eyes of men who hope to possess her, while she values freedom over commitment.

In verse four, Joni openly "loves them all;" each night, a new good time. Is is love? For the moment. Here Joni's prowess as a writer blossoms as she sings, "She has brought them to her senses" – not their senses – and "They have laughed inside her laughter" revealing that it's all good fun; don’t take it too seriously. "She will love them when she sees them," until she moves on. That kind of honest contradiction has always intrigued me. A line from Prefab Sprout comes to mind: "He swore he'd never leave her; he meant it till he did." Yet this was March 1968—the very dawn of the sexual revolution. Women did not have sex outside marriage, certainly not with innumerable partners, and they certainly didn’t talk about it.

In verse four, Joni openly "loves them all;" each night, a new good time. Is is love? For the moment. Here Joni's prowess as a writer blossoms as she sings, "She has brought them to her senses" – not their senses – and "They have laughed inside her laughter" revealing that it's all good fun; don’t take it too seriously. "She will love them when she sees them," until she moves on. That kind of honest contradiction has always intrigued me. A line from Prefab Sprout comes to mind: "He swore he'd never leave her; he meant it till he did." Yet this was March 1968—the very dawn of the sexual revolution. Women did not have sex outside marriage, certainly not with innumerable partners, and they certainly didn’t talk about it. Joni sings it all with a catch in her voice – second thoughts? Regrets? Despite my experience and insight, I don't know; I'm in too deep. I cannot truly fathom a woman's mind. While I created the psyche of my character in Unblinking, can I really understand her at all?Ultimately, "She only means to please them." Am I reading it wrong; reading too much into it: a man's ultimate goal is to achieve pleasure; a woman’s to give it? It's hardwired into our brains and our psyches and our genitalia, and yet "Her heart is full and hollow like a cactus tree." Who knows if a cactus tree really is full and hollow? Go ask a botanist, but who cares? Joni knows, and all I can do is pretend to.

Published on July 08, 2021 14:17

Graham Nash on Joni Mitchell

The following is an excerpt from Graham Nash's article in London's Daily Mail. There is nothing quite like hearing the story, as much as you may already know it, from the source.

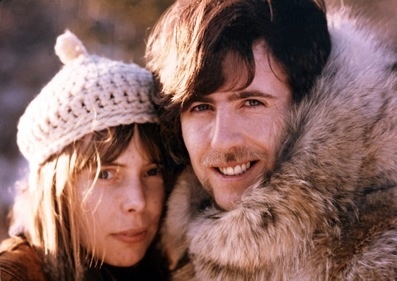

The following is an excerpt from Graham Nash's article in London's Daily Mail. There is nothing quite like hearing the story, as much as you may already know it, from the source.Graham Nash: On an August evening in 1968, the sun was sinking in the western sky as the cab crawled up Laurel Canyon, bathing the Hollywood Hills in a golden flush of summer. We stopped in front of a small wooden house on Lookout Mountain Avenue. Inside, lights glowed and I could hear the jingle-jangle of voices. I leaned on my guitar case – the only baggage I'd carried off the plane at LAX – and considered again where I was and what I was doing here: leaving my country, my marriage and my band, all at once.

...the Hollies and I had come to an impasse. We had grown up together and enjoyed incredible success, but we were growing apart. The same with my marriage: Rosie was off in Spain chasing another man, and I was in Los Angeles, the city that already felt like my new home, to visit Joni Mitchell, who had captured my heart. For just a moment, I hesitated. Sure, I was an English rock star – I had it made. I had co-written a fantastic string of hits with The Hollies. I was friends with the Stones and The Beatles. You could hear me whistle at the end of "All You Need Is Love." But deep down, I was still just a kid from the north of England, and I felt I was out of my element.

Suddenly, Joni was at the door and nothing else mattered. She was the whole package: a lovely, sylphlike woman with a natural blush, like windburn, and an elusive quality that seemed lit from within. Behind her, at the dining room table, were my new American friends, David Crosby and Stephen Stills – refugees, like me, from successful, broken bands. I grinned the moment I laid eyes on them. I had never met anybody like Crosby. He was an irreverent, funny, brilliant hedonist who had been thrown out of The Byrds the previous year. He always had the best drugs, the most beautiful women, and they were always naked.

Suddenly, Joni was at the door and nothing else mattered. She was the whole package: a lovely, sylphlike woman with a natural blush, like windburn, and an elusive quality that seemed lit from within. Behind her, at the dining room table, were my new American friends, David Crosby and Stephen Stills – refugees, like me, from successful, broken bands. I grinned the moment I laid eyes on them. I had never met anybody like Crosby. He was an irreverent, funny, brilliant hedonist who had been thrown out of The Byrds the previous year. He always had the best drugs, the most beautiful women, and they were always naked.Stephen was a guy in a similar mold. He was brash, egotistical, opinionated, provocative, volatile, temperamental, and so talented. A very complex cat, and a little crazy, he had just left Buffalo Springfield, one of the primo L.A. bands.

That night, while Joni listened, the three of us sang together for the first time. I heard the future in the power of those voices. And I knew my life would never be the same.

Joni and I had first met after a Hollies show in Ottawa, Canada in March. I'd seen this beautiful blonde in the corner by herself, and I'd shuffled over and introduced myself. "I know who you are," she said, slyly. "That's why I'm here."

She had invited me back to her room at a beautiful old French Gothic hotel, where flames licked at logs in the fireplace, incense burned in ashtrays and beautiful scarves were draped over the lamps. It was a seduction scene extraordinaire. She picked up a guitar and played me 15 of the best songs I’d ever heard, and then we spent the night together. It was magical on so many different levels.

That evening with Crosby and Stills at Joni's, five months later, was the first time I'd seen her since. After that, I moved out to Los Angeles for good, as soon as I had messily extricated myself from The Hollies. The plan was to crash at Crosby’s house, where a party was always in full swing: beautiful young women all over the place, some clothed, some not so clothed. Music pulsing through the place. Hippy heaven.

On my first night, in the midst of the party, Joni appeared. Taking me by the arm, she said: "Come to my house and I'll take care of you."

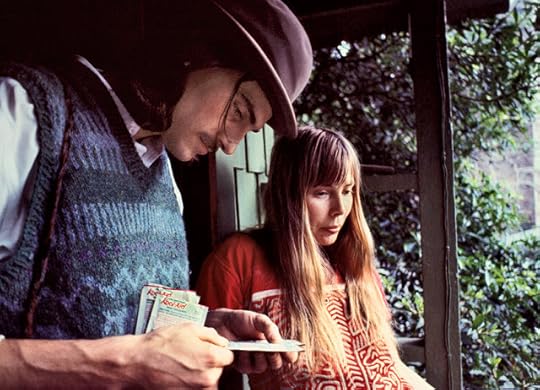

Joni had a great little place, built in the 1930s by a black jazz musician: knotty pine, creaky wooden floors, a couple of cabinets full of beautifully coloured glass objects and Joan's artwork leaning discreetly here and there. From the moment I first heard her play, I thought she was a genius. I’m good at what I do, but genius? Not by a long shot. She was finishing her Clouds album and writing songs for what would become Ladies Of The Canyon.

We both wrote whenever the spirit moved us, but in Joni’s house, when it came to the piano, I always gave way. If she was working there or playing guitar in the living room, I'd head into the bedroom with my guitar or simply take a walk. Occasionally, I lingered in the kitchen, just listening to her play.

Published on July 08, 2021 14:00

More On Ladies of the Canyon

In April 1970 Joni Mitchell released her third LP, Ladies Of The Canyon, an ode to the her neighbors and the Boho neighb of Laurel Canyon, a hillside paradise nestled in the purgatory of Los Angeles. Deep in a relationship with Graham Nash, the songs reflect her homely life. "Willy" and "Blue Boy" are profound, gentle love songs to Nash, while "Morning Morgantown" and "Ladies of the Canyon" offer sweet, romantic smalltown portraits. Some of the lyrics are a bit twee, and others are overly sweet or pretty, but why not; this is paradice; on the surface, anyway. Still there is an underrated power to this record. "For Free" is one of her strongest early songs, exploring the dichotomy between being a wealthy recorded artist and a modest street busker; it also features a dazzling clarinet solo at its climax, hinting at the jazz to come, though not as well as "The Arrangement." Here is one of Joni's first songs to explore jazz structures, if not jazz textures or arrangements. It is her most experimental and challenging song up to this point, and also perhaps the most difficult song to get into. "Rainy Night House" and "The Priest" are two highlights, gems tucked away, as if they were hidden in a rustic cul-de-sac.

In April 1970 Joni Mitchell released her third LP, Ladies Of The Canyon, an ode to the her neighbors and the Boho neighb of Laurel Canyon, a hillside paradise nestled in the purgatory of Los Angeles. Deep in a relationship with Graham Nash, the songs reflect her homely life. "Willy" and "Blue Boy" are profound, gentle love songs to Nash, while "Morning Morgantown" and "Ladies of the Canyon" offer sweet, romantic smalltown portraits. Some of the lyrics are a bit twee, and others are overly sweet or pretty, but why not; this is paradice; on the surface, anyway. Still there is an underrated power to this record. "For Free" is one of her strongest early songs, exploring the dichotomy between being a wealthy recorded artist and a modest street busker; it also features a dazzling clarinet solo at its climax, hinting at the jazz to come, though not as well as "The Arrangement." Here is one of Joni's first songs to explore jazz structures, if not jazz textures or arrangements. It is her most experimental and challenging song up to this point, and also perhaps the most difficult song to get into. "Rainy Night House" and "The Priest" are two highlights, gems tucked away, as if they were hidden in a rustic cul-de-sac. Mitchell's voice is very sweet and girlish here, which is odd considering that she showed a brassier tone on the earlier Clouds. It gives the album a pretty, romantic quality, and the hit "Big Yellow Taxi" is characteristic of the album's guitar-driven songs, which are few. Ladies of the Canyon instead features piano more prominently, a move Mitchell credited to to Laura Nyro, who was, at this time, a more sophisticated and developed artist. Overall, Ladies of the Canyon was an important step forward for Joni Mitchell, adding texture and substance to her previously modest, understated acoustic pieces.

Laurel Canyon is a geographical oddity, a jumble of undeveloped Hollywood hills that butts up to West Hollywood. By 1968, the neighborhood had become the center of the local music scene. Nearly every Los Angeles musician lived there, jammed there, or crashed on somebody's couch there: The Byrds, The Mamas & the Papas, Crosby Stills Nash and sometimes Young, The Beach Boys, The Doors, Love, a few of the Monkees, Frank Zappa, The International Submarine Band, Jackson Browne, and scores more. "It was Brigadoon meets the Brill Building," wrote Michael Walker in his 2006 best-seller Laurel Canyon: The Inside Story Of Rock-and-Roll’s Legendary Neighborhood.

Laurel Canyon is a geographical oddity, a jumble of undeveloped Hollywood hills that butts up to West Hollywood. By 1968, the neighborhood had become the center of the local music scene. Nearly every Los Angeles musician lived there, jammed there, or crashed on somebody's couch there: The Byrds, The Mamas & the Papas, Crosby Stills Nash and sometimes Young, The Beach Boys, The Doors, Love, a few of the Monkees, Frank Zappa, The International Submarine Band, Jackson Browne, and scores more. "It was Brigadoon meets the Brill Building," wrote Michael Walker in his 2006 best-seller Laurel Canyon: The Inside Story Of Rock-and-Roll’s Legendary Neighborhood.The title track paints the area as a loose commune defined by the creative zeal and gregarious spirit of its inhabitants. It's tempting to read real-life counterparts into the three women Mitchell sings about. Is Trina really a stand-in for Szou Paulekas, who recycled vintage clothing into hippie-freak fashion and defined the look of a generation? Might Annie actually be Mama Cass Elliott, widely regarded as the Gertrude Stein of Laurel Canyon? Could Estrella be Joan Baez or Laura Nyro, or even Mitchell herself?

With its steep hills, winding dirt roads, and a handful of man made caves strung with lights, the canyon provided a woodsy refuge from L.A. Along with beautiful views of the city, it offered an escape from the social turmoil that defined the 1960s: the Watts riots in 1965, The Manson Family, the draft, the general sense of societal entropy – what Joan Didion in her essay "The White Album" called "the shifting phantasmagoria which is our actual experience." Ladies of the Canyon is a beautiful album, filled with yearning for the ideal world that was promised by so much of the music and culture of the '60s but by 1970 had been largely given up on (That was just a dream some of us had).

Published on July 08, 2021 13:59

Ladies of the Canyon - The Joni 70s

1970's Ladies of the Canyon was written and recorded at the height of Joni Mitchell's early phase while living in Laurel Canyon, and is a grand debut for the Joni of the 70s. It was here, on Ladies, that Joni started her venture into jazz. The album was produced by Joni, who also played piano, guitar and keyboards with a handful of jazz musicians, including Paul Horn on clarinet and sax. It’s not the lavishly orchestrated jazz of Court and Spark, but the spark is there.

1970's Ladies of the Canyon was written and recorded at the height of Joni Mitchell's early phase while living in Laurel Canyon, and is a grand debut for the Joni of the 70s. It was here, on Ladies, that Joni started her venture into jazz. The album was produced by Joni, who also played piano, guitar and keyboards with a handful of jazz musicians, including Paul Horn on clarinet and sax. It’s not the lavishly orchestrated jazz of Court and Spark, but the spark is there. Deep in a relationship with Graham Nash, the songs reflect her homely life. "Willy" and "Blue Boy" are profound, gentle love songs to Nash, while "Morning Morgantown" and "Ladies of the Canyon" offer sweet, romantic small-town portraits. Some of the lyrics have twee elements, and others are overly sweet or pretty, but there is an often underrated power to Joni’s hippie album. "For Free" is one of her strongest early songs, exploring the dichotomy between being a successful and wealthy recording artist and a modest street busker; it also features a dazzling clarinet solo at its climax.

"The Arrangement" is one of her first songs to explore jazz structures, if not jazz textures or arrangements. It is her most experimental and challenging song to this point, and also perhaps the least accessible. "Rainy Night House" and "The Priest" are two definite highlights, gems tucked away on this album. It takes a while for them to leap out, but they have immense staying power with their gorgeous melodies and heartfelt performances. Mitchell's voice is sweet and girlish here, somewhat odd compared with the deep tone on Clouds. It gives the album a pretty, romantic quality, and the hit "Big Yellow Taxi" is characteristic of the album's guitar-driven songs. "The Circle Game," a Joni Mitchell 'standard,' fits into this category.

Ladies of the Canyon also features piano prominently, a move Mitchell credited to listening to Laura Nyro, who was at this time perhaps a more sophisticated and developed artist. The album is notable for exploring woodwind for the first time, and it's the fullest-sounding of her early acoustic works. It also features her soaring electric piano rendition of "Woodstock."

Overall, Ladies of the Canyon was an important step forward for Joni Mitchell, adding texture and substance to her previously modest, understated acoustic pieces. She would explore these sounds further into the 1970s, but this is the most important albums in her artistic evolution.

Published on July 08, 2021 13:58

Song to a Seagull and Clouds

Recorded in the midst of the Vietnam War and surrounded by sweeping social changes, Joni Mitchell's 1968 underrated debut, Song to a Seagull (AM7), is an elegant and timeless microcosm. The songs are captivating and complex, drawing the listener into a misty and melancholic realm that fills the cracks between genres: a unique artistry that blends the heartfelt simplicity of folk, the rhythmic, youthful allure of rock and the expansive, detail-mindedness of classical. (Later she would incorporate the improvisational, bonds-loosened feel of jazz as well, not yet.) The sound of the recording is atmospheric and for the most part the music broods, yet Joni is the ultimate storyteller and the characters are portrayed with a strong sense of reality: songs about common relationships, people we may have met, emotions we too may feel or thoughts we may have once pondered. We know straight away that this is no average songwriter. Joni draws attention to certain lines in circumspect unfamiliar ways. In "Sisotowbell Lane" she takes the melody from the second to the last line of the verse and repeats it on the second to the last line of the chorus: simple complexity. The lyrics are similar, she holds a note on the verse and cuts off one from the chorus. This clipped note sets up for the last line of the chorus. The projected imagery expands from colorful to so vibrantly tactile you can touch it.

Recorded in the midst of the Vietnam War and surrounded by sweeping social changes, Joni Mitchell's 1968 underrated debut, Song to a Seagull (AM7), is an elegant and timeless microcosm. The songs are captivating and complex, drawing the listener into a misty and melancholic realm that fills the cracks between genres: a unique artistry that blends the heartfelt simplicity of folk, the rhythmic, youthful allure of rock and the expansive, detail-mindedness of classical. (Later she would incorporate the improvisational, bonds-loosened feel of jazz as well, not yet.) The sound of the recording is atmospheric and for the most part the music broods, yet Joni is the ultimate storyteller and the characters are portrayed with a strong sense of reality: songs about common relationships, people we may have met, emotions we too may feel or thoughts we may have once pondered. We know straight away that this is no average songwriter. Joni draws attention to certain lines in circumspect unfamiliar ways. In "Sisotowbell Lane" she takes the melody from the second to the last line of the verse and repeats it on the second to the last line of the chorus: simple complexity. The lyrics are similar, she holds a note on the verse and cuts off one from the chorus. This clipped note sets up for the last line of the chorus. The projected imagery expands from colorful to so vibrantly tactile you can touch it. The album reveals a master at work; not the work of a novice, these aren't the lyrics of a beginner, a flower child or a sophomoric "student" of art, but the uncommon work of a true artist. It's cerebral, beautiful, thought-provoking and mature - free of any pretense. Blue, Court and Spark, the jazz albums are Joni’s shining moments, but Song to a Seagull is quietly brooding magic, Joni's marriage of the earthy and the celestial (captured beautifully in David Crosby understated production). Most important is the imagery apparent within the groves; one can see her there in Laurel Canyon at the piano, David Crosby sitting on the couch behind her, Graham Nash at the dining table scribbling the lyrics to "Our House," the smell of eucalyptus in the air.

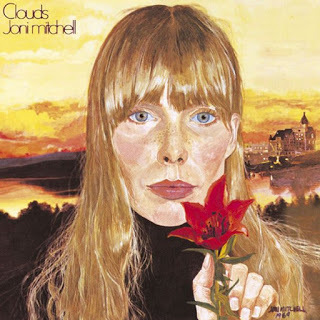

The album reveals a master at work; not the work of a novice, these aren't the lyrics of a beginner, a flower child or a sophomoric "student" of art, but the uncommon work of a true artist. It's cerebral, beautiful, thought-provoking and mature - free of any pretense. Blue, Court and Spark, the jazz albums are Joni’s shining moments, but Song to a Seagull is quietly brooding magic, Joni's marriage of the earthy and the celestial (captured beautifully in David Crosby understated production). Most important is the imagery apparent within the groves; one can see her there in Laurel Canyon at the piano, David Crosby sitting on the couch behind her, Graham Nash at the dining table scribbling the lyrics to "Our House," the smell of eucalyptus in the air. Song to a Seagull was released March 1, 1968, with production beginning sometime after August 1967, when Joni met David Crosby. Joni's second LP, Clouds (AM7) would not be released until May 1969, a long span for the era, offering her the luxury of time that many new artists weren't granted (standard contracts called for two LPs per year). Among Clouds' ten tracks, were her own versions of songs already covered by other artists, including "Chelsea Morning," "Tin Angel," and "Both Sides Now."

Song to a Seagull was released March 1, 1968, with production beginning sometime after August 1967, when Joni met David Crosby. Joni's second LP, Clouds (AM7) would not be released until May 1969, a long span for the era, offering her the luxury of time that many new artists weren't granted (standard contracts called for two LPs per year). Among Clouds' ten tracks, were her own versions of songs already covered by other artists, including "Chelsea Morning," "Tin Angel," and "Both Sides Now.""Both Sides Now," written more than a year before it ran up the charts for Judy Collins in 1968, was inspired by Saul Bellow's Henderson the Rain King on a jetliner; in particular, a passage where the main character is traveling by plane looking out over the clouds. The novel includes the line, "we are the first generation to see the clouds from both sides."

Joni's metaphor alluded to how children see clouds from the ground below, concocting fanciful and innocent images, then, as adults find nothing in them but inclement weather – indeed, both sides, the innocence, the trials and tribulations, the judgments of, let’s call it "the moon and the stars." Joni just didn't understand life or love at all. She was 21. Probably still doesn’t.

Other songs on the Clouds LP, mostly written in late 1967 and early '68, deal with love, lovers, unrequited love, the uncertainty of love, you get the point, in tracks like "I Don’t Know Where I Stand," "Tin Angel," "That Song About the Midway," and "The Gallery." But Clouds also includes "The Fiddle and The Drum," a song that compares America during the Vietnam War to a bitter friend, and "I Think I Understand, which is about mental illness.

In 1969, Joni Mitchell’s Clouds rose to No. 22 on the Canadian chart and No. 31 on the Billboard 200. Mitchell produced all the songs on the album (except for one), played acoustic guitar and keyboards, and was joined by Stephen Stills on bass guitar for just one track. Clouds brought Joni Mitchell a Grammy Award for Best Folk Performance. On Clouds, as well as Song To A Seagull we encounter a woman in a tug of war between innocence and experience. Joni's painterly influence on her compositions is in full evidence on both early LPs, from the Rembrandt browns of "Tin Angel" to the bright golds and yellows of "Chelsea Morning." The experience of innocence: as difficult a concept as the child being father to the man.

Side note: Bill and Hillary Clinton would go on to name their daughter, Chelsea, after the Mitchell track.

We are the first generation to see the clouds from both sides. - Saul Bellow

Published on July 08, 2021 13:57

June 26, 2021

Fahrenheit 451 and "A Remark You Made"

In Ray Bradbury's Fahrenheit 451, a novel in which books are banned and burned, Fireman Montag's vacuous wife tries to commit suicide with pills provided to maintain the public's passivity. The ambulance service that detoxifies her acts as if she were carpet to be cleaned. The "family" to which she returns is not Montag, but strangers on a television screen. His wife's opposite is an oddly optimistic and forthright young girl name Clarisse who asks Montag if he's happy. Later, Montage witnesses an old woman who chooses to be burned alive than to give up her library of books. His metamorphoses as a reader has begun. By novel's end (spoiler), Montag joins a renegade community in which the participants memorize books so that they will always be with us, despite the government edict and the firemen.

In Ray Bradbury's Fahrenheit 451, a novel in which books are banned and burned, Fireman Montag's vacuous wife tries to commit suicide with pills provided to maintain the public's passivity. The ambulance service that detoxifies her acts as if she were carpet to be cleaned. The "family" to which she returns is not Montag, but strangers on a television screen. His wife's opposite is an oddly optimistic and forthright young girl name Clarisse who asks Montag if he's happy. Later, Montage witnesses an old woman who chooses to be burned alive than to give up her library of books. His metamorphoses as a reader has begun. By novel's end (spoiler), Montag joins a renegade community in which the participants memorize books so that they will always be with us, despite the government edict and the firemen. I have always contemplated what my book would be: Gatsby or The Sun Also Rises; Steinbeck or Stranger in a Strange Land. But in music I have one constant, a song I go back to again and again, oddly a jazz instrumental by Weather Report titled "A Remark You Made." Despite its lack of lyrical content, it is the song in which I have over the years memorized every note and nuance, every muted nouveau harmonic trill from Jaco Pastorius, every ostinato of Joe Zawinul's electric piano. I can play each musician's part in my head.

I have always contemplated what my book would be: Gatsby or The Sun Also Rises; Steinbeck or Stranger in a Strange Land. But in music I have one constant, a song I go back to again and again, oddly a jazz instrumental by Weather Report titled "A Remark You Made." Despite its lack of lyrical content, it is the song in which I have over the years memorized every note and nuance, every muted nouveau harmonic trill from Jaco Pastorius, every ostinato of Joe Zawinul's electric piano. I can play each musician's part in my head.Though it's Zawinul's tune, he has stated that it wasn't until Jaco arrived at the studio the next day that the song came alive, that all he'd done was to fill in the blanks left by Shorter and Pastorius.

Joni Mitchell's "California" is my life's theme song; The Cure's "Plainsong" that one song that invariably gives me chills. "Landslide" is what I hope will be the last song I ever hear (a long time from now), but it is "A Remark You Made" that is intrinsic as the incidental soundtrack that loops incessantly through my head.

Published on June 26, 2021 05:32

June 24, 2021

Repost - Jay and the Americans - Joni Mitchell's Blue

Click on the CoverWhen I was six years old, I did a television commercial for St. Joseph's Baby Aspirin that was particularly popular in prime time. A rumor began to circulate that I had died in some kind of tragic accident. My mother got hundreds of letters and phone calls from total strangers: "So terribly sorry about your loss." But it wasn't me. It was another young boy in a different aspirin commercial, and as it turned out, he wasn't dead either. Everything is coincidence. Everything. Let me illustrate.

Click on the CoverWhen I was six years old, I did a television commercial for St. Joseph's Baby Aspirin that was particularly popular in prime time. A rumor began to circulate that I had died in some kind of tragic accident. My mother got hundreds of letters and phone calls from total strangers: "So terribly sorry about your loss." But it wasn't me. It was another young boy in a different aspirin commercial, and as it turned out, he wasn't dead either. Everything is coincidence. Everything. Let me illustrate.High above the grid, my father sat with a cup of coffee, his feet dangling from the side of a billboard, gazing out over a basin still filled with fog and night. You can't paint when it's damp. He looked up into the cosmos, into the luck and the endless happenstance, savoring that cup of Joe. It was 1971. I was ten. He perused his schematic, this one all blues: a quart of Endless Blue, Blue Yonder, Blue Stencil, Sistine Blue, and Pompeii; two gallons of dark blue 123505, same as the night; one gallon of bright white.

Two of his best billboards already graced the boulevard that year: L.A. Woman, that iconic hot point silhouette of Jim Morrison crucified on a phone pole, all in earthy browns; the Stones' Sticky Fingers and now Joni Mitchell's Blue. He'd made no name for himself, that wasn't even the goal, but nowadays thousands of commuters gazed up at him or his work or him at his work. More than once someone was rear-ended because somebody else was looking up at my father and not at the road. He got a kick out of that. He was a master forger, like someone out of the Renaissance, like one of Titian's toadies, and that was good enough for my old man.

Two of his best billboards already graced the boulevard that year: L.A. Woman, that iconic hot point silhouette of Jim Morrison crucified on a phone pole, all in earthy browns; the Stones' Sticky Fingers and now Joni Mitchell's Blue. He'd made no name for himself, that wasn't even the goal, but nowadays thousands of commuters gazed up at him or his work or him at his work. More than once someone was rear-ended because somebody else was looking up at my father and not at the road. He got a kick out of that. He was a master forger, like someone out of the Renaissance, like one of Titian's toadies, and that was good enough for my old man.But not for my mother. That was the thing, that's the point of this apostrophe. Nothing was ever good enough for my mother. Not her career, not my father, not the house. They were happy and dissatisfied, satisfied and regretful, all and nothing at all, boundless and limited, opposites attracted by bad timing and dumb luck. It's how they met; it's how they parted; it's how they said their last words to one another.

By midday he was working on the face, Joni's high cheekbones in silver and Endless Blue. By three he was finishing up, a detail here and there, smoothing a line, adding a dab of white or a little splotch of cerulean that wasn't on the schematic.

"That’s the record I did," my mother said. We were turning left onto Laurel Canyon from Sunset. Joni Mitchell's Blue was all but complete, a masterwork; a man on scaffolding was finishing up a white Reprise logo in the corner, instead of signing his name. My mother sang backup on three songs that hadn't made the final cut, but Joni said she had a future. She didn't; all she had was resentment."That’s dad." My mother turned left. "You're not going to stop?"

"That’s the record I did," my mother said. We were turning left onto Laurel Canyon from Sunset. Joni Mitchell's Blue was all but complete, a masterwork; a man on scaffolding was finishing up a white Reprise logo in the corner, instead of signing his name. My mother sang backup on three songs that hadn't made the final cut, but Joni said she had a future. She didn't; all she had was resentment."That’s dad." My mother turned left. "You're not going to stop?""You want me to stop?"

"I want you to stop."

Big argument about stopping, about turning around. At a light, I got out of the car and started walking down the canyon sidewalk. "You get in the car. You get in this car." Her voice trailed off. It was probably the first defiant moment of my life.

"Can I come up?" I asked him.

"You can't come up."

"I need to talk to you."

"I’m coming down. I’m done." He was every shade of blue. He had blue in his hair. His lips were blue; he'd stick a paintbrush in his mouth to flatten out the bristles. One of his fingers was silver with powder blue dots. My father was hesitant. "How'd you get here?"

"Got out of the car." I told him the story. He kind of chuckled. My mother pulled into the parking lot behind us. You would have thought my father yanked me from out of the back seat while it was moving. She couldn't have been more livid, more enraged. My father kept looking at me in a quandary. We didn't know what she was saying, as if she were speaking in tongues, until she said, "Fine. Is that what you want? You want him, fine. I’m done, I’m done. I’m absolutely done." She got into the car and drove away. "You want him?" she said like she was giving away the dog.

Jay and the Americans is available all over the world!

Kindle too!

CreateSpace - Amazon - Amazon UK - Amazon France - Amazon Russia

Published on June 24, 2021 06:11

June 21, 2021

The Only Band That Matters

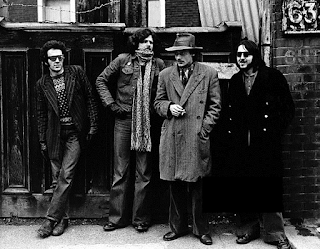

The 101ersFormed as the first shots of the punk revolution were fired, The Clash stormed onto the British scene with their debut performance on July 4, 1976, at The Black Swan in Sheffield, England, as the opening act for The Sex Pistols. While America celebrated the Bicentennial anniversary of its independence from Britain, the U.K. was in the midst of another revolution, this one staged on its very own shores. One eyewitness was Joe Strummer, then the frontman of a popular pub-rock band called the 101ers. Before a gig at a London club called the Nashville Room in April 1976, he watched as that night's opening act took the stage: "Five seconds into their first song, I just knew we were like yesterday's papers. I mean, we were over." The group was The Sex Pistols, and their effect on Strummer was life-altering. Within weeks, he'd accepted an invitation from guitarist Mick Jones and bassist Paul Simonon to leave the 101ers and join their as-yet-unnamed and drummer-less new band. Together, the three of them would form the core of a group their fans would call, with all sincerity, The Only Band That Matters. If you're doing the math, it took just three months for that catalytic first gig to be actualized.

The 101ersFormed as the first shots of the punk revolution were fired, The Clash stormed onto the British scene with their debut performance on July 4, 1976, at The Black Swan in Sheffield, England, as the opening act for The Sex Pistols. While America celebrated the Bicentennial anniversary of its independence from Britain, the U.K. was in the midst of another revolution, this one staged on its very own shores. One eyewitness was Joe Strummer, then the frontman of a popular pub-rock band called the 101ers. Before a gig at a London club called the Nashville Room in April 1976, he watched as that night's opening act took the stage: "Five seconds into their first song, I just knew we were like yesterday's papers. I mean, we were over." The group was The Sex Pistols, and their effect on Strummer was life-altering. Within weeks, he'd accepted an invitation from guitarist Mick Jones and bassist Paul Simonon to leave the 101ers and join their as-yet-unnamed and drummer-less new band. Together, the three of them would form the core of a group their fans would call, with all sincerity, The Only Band That Matters. If you're doing the math, it took just three months for that catalytic first gig to be actualized. That first live gig had its predictable rough patches, but their enthusiasm and commitment were there from the start, as were their unique musical and visual aesthetics. The Clash were instantly distinguishable from the Pistols by virtue of their sincere political bent, one that wasn't just a part of the problem, but a part of the solution. While The Sex Pistols sneered and preached anarchy, there was always a barely disguised element of lazy hucksterism in their social agenda. The Clash, on the other hand, quickly established themselves as the zealous and decidedly un-soft advocates of leftist causes. As U2 guitarist, The Edge later wrote, "This wasn’t just entertainment. It was a life-and-death thing. They made it possible for us to take our band seriously. It was the call to wake up, get wise, get angry, get political and get noisy about it."

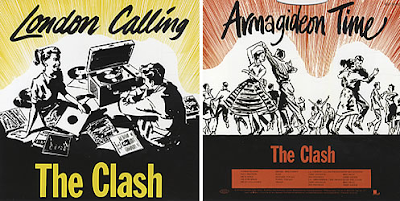

That first live gig had its predictable rough patches, but their enthusiasm and commitment were there from the start, as were their unique musical and visual aesthetics. The Clash were instantly distinguishable from the Pistols by virtue of their sincere political bent, one that wasn't just a part of the problem, but a part of the solution. While The Sex Pistols sneered and preached anarchy, there was always a barely disguised element of lazy hucksterism in their social agenda. The Clash, on the other hand, quickly established themselves as the zealous and decidedly un-soft advocates of leftist causes. As U2 guitarist, The Edge later wrote, "This wasn’t just entertainment. It was a life-and-death thing. They made it possible for us to take our band seriously. It was the call to wake up, get wise, get angry, get political and get noisy about it."It took some months following their debut gig for the Clash to work out the kinks and find Topper Headon (drums), who would complete their definitive lineup. Even 25 years later, Joe Strummer could still quote nearly verbatim one of their early reviews: "The Clash are one of those garage bands who should be swiftly returned to the garage, with the doors locked and with the motor left running." Undiscouraged, the Clash released an acclaimed, self-titled debut album in the spring of 1977, and over the next two-and-a-half years, they released a second album, Give 'Em Enough Rope (1978), that was Rolling Stone's pick for album of the year, and a third, London Calling (1979), that the same magazine chose as the ultimate LP of the 1980s.

The band’s first single “White Riot” was as punk as punk gets, demanding "a riot of our own," but even by the time their debut LP came around, they were embracing reggae and generally proving more musically visionary than their contemporaries, embracing the idea of punk as a liberating force, not a studded creative straitjacket. They were the existentialists to the Pistols' nihilism, a band who wanted to rebuild the world rather than cavort gleefully in its ruins. And so, while punk devolved into fundamentalism, a home for a gazillion bands with mohawks who mistook the "Here's three chords, now form a band" idea for a veneration of ineptitude and ignorance, The Clash expanded their horizons.

London Calling and Sandinista!, in particular, took the idea of deconstructing music and ran with it, finding the band romping adeptly through the history of rock 'n' roll. And, just as unfashionably, the band had something to say. Earnestness has long been seen as a death sentence in pop music, the polar opposite of a rock stance that's too cool to care about anything at all. But for a while, The Clash managed to transcend this, singing about the Spanish Civil War and capitalist alienation and a wealth of other topics, and did it with a degree of eloquence and intelligence that would be lost on the majority of their contemporaries.

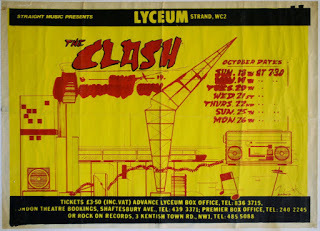

For me, The Clash remain a band of the era, difficult to embrace in our post-millennial world. The issues remain, but even London Calling loses something in the time translation. Doesn't matter; The Clash weren't about vinyl, but about being there, and for me, though it was just once, it was one of those moments "come unstuck in time." The Roxy, April 27, 1980. Oh my God, "Stay Free," "Somebody Got Murdered," "Safe European Home," Kenya crying that they didn't do "Lost in a Supermarket," everyone tripping. This was the venue where, not more than a month later, Rickie Lee Jones and Tom Waits accused me of stealing Rickie's beret, where The Go-Go's played on Sundays, where Darby Crash used my head instead of the banister while Laura gave me head on the stairs - I loved the Roxy). The Clash are a fixture of my nostalgia and all I have to hear is "Tommy Gun" and I'm right back there taking Laura by the hand, "Come on. Let's go back stage."

For me, The Clash remain a band of the era, difficult to embrace in our post-millennial world. The issues remain, but even London Calling loses something in the time translation. Doesn't matter; The Clash weren't about vinyl, but about being there, and for me, though it was just once, it was one of those moments "come unstuck in time." The Roxy, April 27, 1980. Oh my God, "Stay Free," "Somebody Got Murdered," "Safe European Home," Kenya crying that they didn't do "Lost in a Supermarket," everyone tripping. This was the venue where, not more than a month later, Rickie Lee Jones and Tom Waits accused me of stealing Rickie's beret, where The Go-Go's played on Sundays, where Darby Crash used my head instead of the banister while Laura gave me head on the stairs - I loved the Roxy). The Clash are a fixture of my nostalgia and all I have to hear is "Tommy Gun" and I'm right back there taking Laura by the hand, "Come on. Let's go back stage."Go easy, step lightly, Stay Free...

When I left L.A., I was listening to Gentle Giant and Jetro Tull, "Bohemian Rhapsody" was on the radio - so it was 40 years ago. My parents, meaning my mother and my step, were done with L.A., and my father'd already moved on, opened his studio in an old 5 & Dime in Jerome, Arizona (a ghost town resurrected by the art community), and he didn't have the time for me. I didn't want to go. Nicki Onstad was my first girl and she'd taught me things, lot of firsts revolve around my meeting Nicki, and I can still hear her today. "I just love marijuana." It was a part of the last conversation we had, the night before all our shit was crammed into a Dodge Dart and we drove off leaving L.A. behind. I was 16.

I wrote to her, sent her postcards, and I called from Yuma, Arizona and Fort Stockton, Texas; from the middle of nowhere. I was the one who left, but she'd already moved on. There was, nonetheless, this sense of sabotage in the back of my mind that the whole scheme to leave L.A. would implode, and we'd be back and Nicki and I would get high and stay that way happily ever after. In the meantime it was the back seat of the Dodge all to myself, like a traveling wigwam, me and my music and the Indian blanket my Father bought me in Monument Valley. I had four 8-Track tapes I'd made: Tull, Yes, ELP. The end of an era.

In 1980, I went home. Three years passed. I saved the money to buy a pale yellow 1973 Austin America. I took I10 all the way to Hollywood and checked into a cheap motel on La Cienega; then I drove straight to Sunset Blvd. It was a crisp, cool March evening and the billboards were lit up, yet everything had changed; it wasn't mine anymore. The sounds and visions in my head were somewhere in between 1968 and 1976. This was L.A. Where were the singer/songwriters driving old Porsches down from Laurel Canyon? Where were the GTOs? Hell, where was David Crosby? The billboards were lit up, but L.A. was dark. Punk made its mark and my Stoned-Pony hippie town gave way to X, The Plugs, Circle Jerks, and an assortment of post-punk jittery, hopped-up slam bands. Metallica was playing The Starwood. There was an erotic bakery next to the Whiskey. Piercings and black leather were everywhere (there wasn't a jeans jacket to be found). Clearly I'd have to adjust.

I called a girl I'd known since Van Nuys High, the singer in a band called Ella and the Blacks. I crashed at her apartment for a month, until she got sick of it. I contemplated leaving again, my city had turned its back. Then, on a Saturday in April at Danny's Oki-Dog, I met Kenya and Cathy and Laura. They were on the list at the Roxy; did I want to go? They liked my car. They needed a ride. The band was The Clash. The sun was going down on a hazy L.A. Fuck yeah, city in the smog, city in the smog; don't you wish that you could be here, too?

Published on June 21, 2021 08:13

June 16, 2021

Pop Lit 101 – The Sensual World on Bloomsday

For the title track of The Sensual World, Kate Bush planned to take Molly Bloom’s soliloquy from James Joyce’s Ulysses, a sublime un-punctuated mess of text, and put it to music. Unable to secure the rights from the Joyce estate, Bush wrote her own version of Molly’s soliloquy, incorporating elements of the original text while creating something uniquely her own. In 2011, the Joyce estate finally granted Bush’s request, and she recorded an alternate version for the Director’s Cut LP that quotes Ulysses verbatim. The track is rhythmically punctuated by Bush singing, “Mmm, yes,” evoking Molly Bloom’s repetition of the word near the end of the book. Adorning these words, Davy Spillane plays the uilleann pipes, a traditional Irish instrument, the melody adapted from a Macedonian dance. By recontextualizing language in song, Bush gives form to formless text, the music creating the track’s punctuation and grammar and in this way, Molly is able to step “out of the page into the sensual world.” Those who have actually read Ulysses (there may be hundreds of them) are able to create a music in their heads that does exactly what Bush has done. In reality, Joyce’s lack of punctuation, relying instead on flow, is rather easily remedied by simply reading as one speaks.

For those who need more background, today is Bloomsday, the day when the 24 hours of Ulysses takes place. Based on the number of words that people speak on average, Ulysses is told over one day in 1904 (the day of Joyce and Nora Barnacle’s first date), now celebrated as Bloomsday. It was Joyce’s intention for the novel to have Homeric parallels and Molly, the wife of Leopold Bloom, represents Penelope. Unlike her mythical counterpart, Molly is having an adulterous affair with Hugh ‘Blazes’ Boylan after ten years of celibacy. Her celebrated internal monologue, which concludes the novel, takes the form of eight enormous “sentences,” with only two marks of punctuation in the episode. Molly accepts Leopold into her bed, frets about his health, and then reminisces about their first meeting and her first feelings of love for him. The episode both begins and ends with “yes”, a word that Joyce described as “the female word.” Earlier, Leopold had been having a cheese sandwich and glass of Burgundy in Davey Byrne’s pub and thinking of the moment in the spring or summer of 1888 when Molly agreed to marry him, among the ferns and rhododendrons on Howth Head with just a comical nanny-goat to witness it. This deeply romantic reminiscence, parts of which recur several times in Ulysses, includes the description of Molly passing the warm and chewed seed cake from her mouth to his. Their love, at least sixteen years before, was passionate, erotic and vital.The song opens with the sound of church bells, perhaps echoing Leopold’s proposal to Molly on Howth Head. Of it, Kate said, “I’ve got a thing about the sound of bells. It’s one of those fantastic sounds: a sound of celebration. They’re used to mark points in life; births, weddings, deaths, but they give this tremendous feeling of celebration. In the original speech Molly’s talking of the time when Leopold proposed to her, and I just had the image of bells, this image of them sitting on the hillside with the sound of bells in the distance. In hindsight I also think it’s a lovely way to start an album. A feeling of celebration that puts me on a hillside somewhere on a sunny afternoon.”“The Molly Bloom of Joyce's soliloquy escapes the confines of his text, ‘stepping out of the page into the sensual world,’ to enjoy the ‘down of a peach,’ the ‘kiss of seedcake,’ to ‘wear a sunset,’ where bodies roll ‘off of Howth Head and into the flesh.’ Kate described the album as her first to really explore "positive female energy" – "I think it's to do with me coming to terms with myself on different levels," she told NME. "In some ways, like on Hounds Of Love, it was important for me to get across the sense of power in the songs that I'd associated with male energy and music. But I didn't feel that this time and I was very much wanting to express myself as a woman in my music rather than as a woman wanting to sound as powerful as a man. And definitely 'The Sensual World', the track, was very much a female track for me. I felt it was a really new expression, feeling good about being a woman musically".

Kate Bush was thirty-one when the single came out, and it has been thirty-one years since the track’s release.

Here's my video for Bloomsday: https://youtu.be/-PMetaIAaeA

Published on June 16, 2021 06:12