R.J. Stowell's Blog: rjsomeone, page 44

August 4, 2019

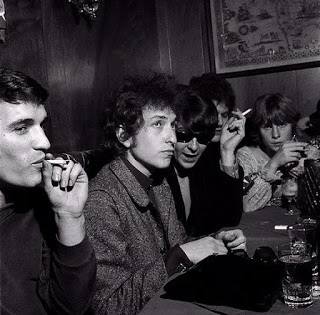

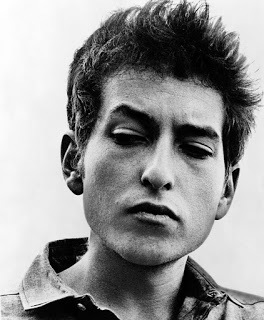

Bob Dylan and The Band - The Seeds of Woodstock

In 1965, Mary Martin, who was working for Bob Dylan's manager Albert Grossman, suggested to Dylan that The Hawks, which included Levon Helm, Robbie Robertson, Harvey Brooks and Al Kooper, might be the perfect accompaniment to the new electric tour. The Hawks were engaged in a four-month stand at Tony Mart's in Somers Point, New Jersey, playing before a nightly crowd of over a thousand with their heady brew of blues and R&B.

In 1965, Mary Martin, who was working for Bob Dylan's manager Albert Grossman, suggested to Dylan that The Hawks, which included Levon Helm, Robbie Robertson, Harvey Brooks and Al Kooper, might be the perfect accompaniment to the new electric tour. The Hawks were engaged in a four-month stand at Tony Mart's in Somers Point, New Jersey, playing before a nightly crowd of over a thousand with their heady brew of blues and R&B.  Dylan checked them out and hired Robertson initially for two gigs in late August at Forest Hills Tennis Stadium in New York and the Hollywood Bowl in Los Angeles. Robertson, unimpressed with Dylan's drummer, suggested Dylan also hire Helm. From there, Robertson, Helm, Harvey Brooks on bass and Al Kooper on keyboards were hired on to endure the cacophony of boos that greeted Dylan's second and third electric gigs. (The first was the Newport Folk Festival, where Dylan was backed by Al Kooper and members of the Butterfield Blues Band. Kooper would go on to form Blood, Sweat and Tears shortly thereafter.)

Dylan checked them out and hired Robertson initially for two gigs in late August at Forest Hills Tennis Stadium in New York and the Hollywood Bowl in Los Angeles. Robertson, unimpressed with Dylan's drummer, suggested Dylan also hire Helm. From there, Robertson, Helm, Harvey Brooks on bass and Al Kooper on keyboards were hired on to endure the cacophony of boos that greeted Dylan's second and third electric gigs. (The first was the Newport Folk Festival, where Dylan was backed by Al Kooper and members of the Butterfield Blues Band. Kooper would go on to form Blood, Sweat and Tears shortly thereafter.)Dylan wanted Robertson and Helm to continue backing him in his attack on middle America's consciousness, but the pair responded that they couldn't see doing it without the rest of The Hawks, which also included Rick Danko and Richard Manuel. After rehearsal in Toronto in September 1965, Bob Dylan and the Band took to the road; the moniker, of course, would stick.

They then moved to Dylan's Catskill home of Woodstock and every week they would fly out on Dylan's private Lodestar airplane, play two or three nights before an audience of "folkie purists" engrossed in ritual booing, regarding an electric Dylan as a sellout to the values of folk music (rather than comprehending music that was years ahead of its time). For many, an electric Dylan was nothing but betrayal; Peter could have done no worse.

They then moved to Dylan's Catskill home of Woodstock and every week they would fly out on Dylan's private Lodestar airplane, play two or three nights before an audience of "folkie purists" engrossed in ritual booing, regarding an electric Dylan as a sellout to the values of folk music (rather than comprehending music that was years ahead of its time). For many, an electric Dylan was nothing but betrayal; Peter could have done no worse.The negativity quickly became too much for Helm, who left and headed back south. "I don't think Levon could handle people just booing every night," said Robertson. "He said, 'I don't want to do this anymore.' He didn't feel that you could do anything with it rhythmically and there was no room and there was no way to make it feel good. To me it was like 'Yeah, but the experience equals this music in the making. We will find the music. It will take some time but we will find it and eventually we'll make it something that we need to get out of it.'"

The experience culminated in late May 1966 at the Royal Albert Hall in London. Columbia Records recorded the event for a possible live LP. The recordings show that, indeed, Dylan and the Band had discovered "this thing". an entity that continually ebbed and flowed as quiet sections alternated with moments of awesome volume and apocalyptic power.

Skip ahead a year. "The next I knew," said Danko, "I found that big pink house that was in the middle of a hundred acres with a pond. It was nice." Danko, Manuel and Hudson all moved into the house, while Robertson ensconced himself nearby. "Everyone remembers the period very fondly. It was the first time since they were kids that they hadn't been on the road. It was the first occasion that they had space, room to breathe, time to think about what they were doing."

The Band at the Big PinkHudson felt similarly: "It was relaxed and low-key, which was something we hadn't enjoyed since we were children. We could wander off into the woods with Hamlet [their gigantic dog]. The woods were right outside our door."

The Band at the Big PinkHudson felt similarly: "It was relaxed and low-key, which was something we hadn't enjoyed since we were children. We could wander off into the woods with Hamlet [their gigantic dog]. The woods were right outside our door."Every day Robertson, Danko, Manuel, Hudson and Dylan would congregate at what had come to be referred to as "The Big Pink," and for two or three hours they would write songs, throw ideas back and forth, play older songs from a multiplicity of genres and occasionally lay some of it down on a two-track recorder in the basement. It was there in Woodstock that the Band, still under Dylan's tutelage, became The Band.

Published on August 04, 2019 06:28

July 31, 2019

Miles From Nowhere

Miles From Nowhere, which is, of course, a novel about Woodstock, is available on Amazon, and for your Kindle! We've kept the price affordable and also arranged for you to read the novel on Kindle Unlimited for free, order the Kindle version for $2.99 or the softbound copy for $10.99. Miles From Nowhere is a rock 'n' roll pilgrimage, the journey of a young man in poor health as he travels from California to Woodstock to see his idol, Jimi Hendrix. Along the way he meets friends and family, an entourage of hippies and bohemians, musicians and socialites; every time you put the novel down you'll have another familiar song in your head.

Miles From Nowhere, which is, of course, a novel about Woodstock, is available on Amazon, and for your Kindle! We've kept the price affordable and also arranged for you to read the novel on Kindle Unlimited for free, order the Kindle version for $2.99 or the softbound copy for $10.99. Miles From Nowhere is a rock 'n' roll pilgrimage, the journey of a young man in poor health as he travels from California to Woodstock to see his idol, Jimi Hendrix. Along the way he meets friends and family, an entourage of hippies and bohemians, musicians and socialites; every time you put the novel down you'll have another familiar song in your head. Order your copy of Miles From Nowhere on Amazon or click the links in the sidebar. (In some markets, availability may be delayed a few days.) Order here on the website and get a personally autographed copy!

Published on July 31, 2019 07:01

July 30, 2019

A Woodstock Interlude

Yesterday, I once again had the opportunity to get to Woodstock for a book signing, and more specifically to Bethel Woods where the festival actually took place (some 50 miles away). I wasn't there in '69, I would have been 8 years old (wouldn't that have been a hoot?), still there was a great sense of emotion that I shared with those at the museum and in town, and those who had been there or more readily experienced the era. Not to mention the ability to share that emotion, or the awe of it, with my son. As a Californian, I would have been much more likely to gravitate to Monterey Pop, but honestly, despite its immensity and my California bias, Monterey was a concert; Woodstock was a life-altering event, even for those us who weren't there. When you read Miles From Nowhere, you'll get that sense of wonder as well.*

Yesterday, I once again had the opportunity to get to Woodstock for a book signing, and more specifically to Bethel Woods where the festival actually took place (some 50 miles away). I wasn't there in '69, I would have been 8 years old (wouldn't that have been a hoot?), still there was a great sense of emotion that I shared with those at the museum and in town, and those who had been there or more readily experienced the era. Not to mention the ability to share that emotion, or the awe of it, with my son. As a Californian, I would have been much more likely to gravitate to Monterey Pop, but honestly, despite its immensity and my California bias, Monterey was a concert; Woodstock was a life-altering event, even for those us who weren't there. When you read Miles From Nowhere, you'll get that sense of wonder as well.*A man with a long white beard sat next to my son on a psychedelic school bus made to emulate the Merry Prankster's Further. During a short film inside the bus, the man said, "That was the music they were playing when I came home from Vietnam." "So you didn't get to Woodstock?" my son asked. He said, "My country had something else in mind." It was the kind of buzz that permeated the building. I would maintain that many of the performances - Jefferson Airplane, Hendrix, Janis - were better in Monterey, but if that kind of vibe was evident in a museum on a chilly fall day, 48 years hence, I can't even imagine what it was like to have been there.

One of the museum's key attractions is a 40-foot film screen surrounded by scaffolding reminiscent of the stage at the Aquarian Exposition. The festival's history is told through interviews of concert goers, locals and promoters. Joe Cocker’s cover of the Beatles' "With a Little Help From My Friends," which turned the lightweight Ringo ditty into a bluesy, cataclysmic rocker, is featured prominently. His soul-baring version of the song was arguably the highlight of the generation-defining festival, rivaled only by Jimi Hendrix' electric version of "The Star-Spangled Banner." Interestingly, Cocker was a virtual unknown before his performance at Woodstock, at least in the U.S., despite a successful debut LP. No one knew of his quirky stage presence, and few were prepared for the emotional aura that Cocker would create that day.

Joe Cocker's voice has always been highly praised or even more severely chided, but one cannot overlook the musicianship of the Grease Band. Alan Spenner (bass), Chris Stainton (keyboards), Henry McCullough (lead guitar), Neil Hubbard (rhythm guitar), and Bruce Rowland (drums), all as obscure as Cocker at the time, sound like an R&B Symphony. Spenner and McCullough's fretwork is raw, Stainton fills the gaps with his B-3 and Wurlitzer piano, and Rowland covers the job of a full percussion section. It is possibly the best performances by a band no one knew, in a time when there were plenty of those (Big Brother and the Holding Company come to mind).

Having been on the road and touring, Joe and the Grease band were well rehearsed, with incredible arrangements of Dylan's, "Just Like A Woman" and "I Shall Be Released" that have intense emotional overtones few young singers could match (Dylan included). His take on the classic "Let's Go Get Stoned," is far superior at Woodstock to even the fine version on the live album, Mad Dogs & Englishmen. "I Don't Need No Doctor," the hit, "Feeling Alright", and tunes like "Dear Landlord” made for a set that was far superior to any of the parts, magnificent as many of them were. The set ends, of course, with Cocker’s majestic take on "With A Little Help From My Friends," a performance that essentially stole the show and put Cocker on the map as a major rock 'n' roll draw. When one thinks of Woodstock, Joe Cocker, in his multi-colored tie-dyed t-shirt, is the most enduring symbol of a historic musical event. I can hear him now in my head.

AM is supported through the sales of Miles from Nowhere and from Jay and the Americans. Read both for free on Kindle Unlimited, or get the Kindle edition (Miles - $2.99; Jay - $5.99) or the trade paperbacks (Miles - $10.99; Jay - $12.99) by clicking the link in the sidebar.

And remember to listen to AM on Daybreak USA and iHeartRadio!

*I must have been six when my mother and her beau, a studio musician, took me to the KPFK Fantasy Faire in Marin County. I proceeded to get lost among the hoards and my mother spent the day frantic, looking for me. I wasn't lost at all, in my book, just on a journey. My mother tells that story all the time, never once mentioning that during her search, The Doors were playing in the background. That she says she doesn't remember.

Published on July 30, 2019 08:18

July 27, 2019

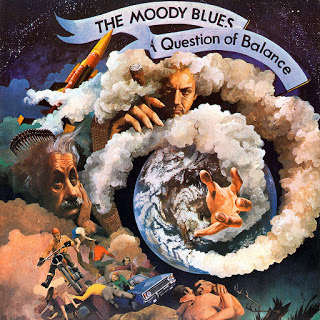

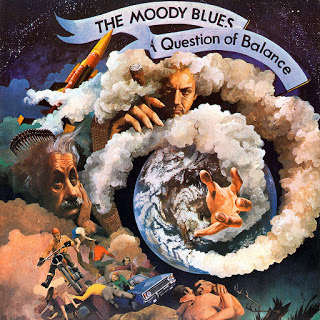

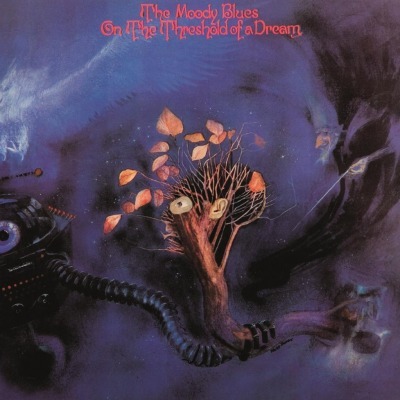

The Moody Blues and Phil Travers

I wasn't cool enough to be a part of the 60s, and not just because I wasn't old enough. I was there, born early in the decade, and, as you'll find when you finally read Jay and the Americans, my informative early years were shaped by 60's TV and rockets to the moon, by Space Food Sticks (you have to remember those) and The Monkees, but had I been in my teens, or in high school as the Summer of Love fell like fall leaves (and not the pretty yellow ones; the brown crumbly ones), I still wouldn't have been cool enough to immerse myself in this mesmerizing culture. I was cool enough in the 80s, for R.E.M. and New Order, but as it lay, I was The Monkees and not The Beatles, let alone The Moody Blues. And yet…

While my brother was cool enough to embrace Days of Future Passed, I didn't understand it. The songs were hidden amidst all that old people music (while my grandmother loved Nancy Sinatra's "These Boots Are Made For Walkin'," the music coming out of the Magnavox console stereo in our home was more likely Montovani and Ferrante and Teicher or 101 Strings' versions of Beethoven; and Days of Future Passed sounded more like that to me than the pop strains of Headquarters. And yet…

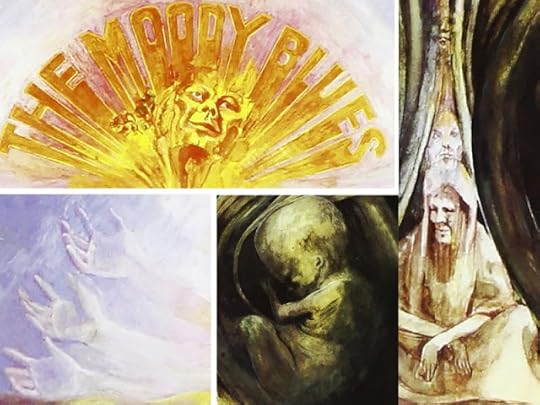

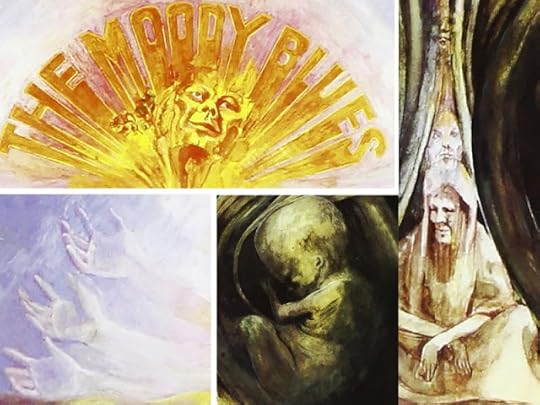

My brother got me In Seach of the Lost Chord for my birthday in 1968. I didn't want it, of course; he did, and he bought it in stereo so that I couldn't play it in my room and only on the Magnavox. (He got me Blood, Sweat and Tears too. Didn't want that either.) But I couldn't take my eyes off the cover, that hypnotizing painting by Phil Travers, who would work with the Moodys on six occasions. Like Hipgnosis' Storm Thorgerson and Pink Floyd, Travers was like another member of the band.

"I met the Moodys," he said, "in a London pub, and we worked out the details of the commission. They invited me down to the studio shortly after that first meeting to listen to the album. So I got an early taste for what they were doing. I liked it. And that's the way it always worked with them. I'd get to listen to the record, then discuss the themes and ideas behind it, before any art concepts were developed.

"The band wanted me to illustrate the concept of meditation. This was not something that I had much personal experience of, and so my early thoughts about the subject were, unfortunately, insubstantial. My first rough designs really reflected a lack of ideas. I began to panic a bit as time was running out, when that image I mentioned in the glass window, of a figure ascending, came back to me and everything then fell into place. I had days rather than weeks to complete the illustration, and submit it for approval. I used Gouache and some water colour to get the effect I was after."

Sometimes it’s the aesthetics of an LP that sparks our interest ( I can still visualize Nancy Sinatra in her go-go boots), and while we can argue over the validity of modern music (the tepid pop charts, the insufferable rap and its lack of musicality), one of the greatest losses that I've found since the advent of the CD and now MP3s and Spotify, is the disassociation of music with the visual. In the 60s, you wanted to peel that Velvet Underground banana or unzip Jagger's Levis, you had the Dark Side post cards on your bulletin board and you displayed Goodbye Yellow Brick Road like it was artwork, only to pick it up, open it and use the gatefold to roll a joint.

Sometimes it’s the aesthetics of an LP that sparks our interest ( I can still visualize Nancy Sinatra in her go-go boots), and while we can argue over the validity of modern music (the tepid pop charts, the insufferable rap and its lack of musicality), one of the greatest losses that I've found since the advent of the CD and now MP3s and Spotify, is the disassociation of music with the visual. In the 60s, you wanted to peel that Velvet Underground banana or unzip Jagger's Levis, you had the Dark Side post cards on your bulletin board and you displayed Goodbye Yellow Brick Road like it was artwork, only to pick it up, open it and use the gatefold to roll a joint.

Anyway, it was a birthday present, but it was its cover that brought my attention to the highly overlooked Moodys. In retrospect, they'd done the symphony thing and pulled it off with flying colors, but this follow-up was 100% Moody Blues. Of the 33(!) different instruments used on the LP, each was played by the band. They earned the nickname of "the world's smallest symphony orchestra."

The LP is a journey, from beginning to end, in search of the chord and ephemeral whatnot. There is a heavy Eastern Philosophical influence, especially on the Mike Pinder contributions ("Best Way to Travel," "Om") and the tracks flow into each other seamlessly, making it one contiguous work of early world music. In every song, the singer yearns for something that cannot be defined. Mike Pinder's searing mellotron and Ray Thomas's soaring flute are the definitive sounds of the album, while the lyrics are a fanciful journey like Coleridge or Shelley.

The LP is a journey, from beginning to end, in search of the chord and ephemeral whatnot. There is a heavy Eastern Philosophical influence, especially on the Mike Pinder contributions ("Best Way to Travel," "Om") and the tracks flow into each other seamlessly, making it one contiguous work of early world music. In every song, the singer yearns for something that cannot be defined. Mike Pinder's searing mellotron and Ray Thomas's soaring flute are the definitive sounds of the album, while the lyrics are a fanciful journey like Coleridge or Shelley.

Of course, this is the album that yielded two of the Moody's most enduring concert pieces, "Ride My See-saw" and the psychedelic "Legend of a Mind." Another standout is "The Actor," a Justin Hayward penned ballad so haunting it matches "Nights in White Satin." Then there's the lovely "Voices in the Sky," and John Lodge's epic, expermental "House of Four Doors," which samples musical styles throughout history. When I was 7, that one was key for me. Lost Chord is loaded with beautiful, experimental music. Why this band is so often overlooked, especially as a part of the Prog Rock era, I'll never know.

An aside: Other LPs bought because of their covers: the velvet wrapped Odessa, by the BeeGees, Brain Salad Surgery, Coltrane's Blue Train, Sinatra's In the Wee Small hours of the morning, Unknown Pleasures, Houses of the Holy, Captain Fantastic. Just a smattering.

While my brother was cool enough to embrace Days of Future Passed, I didn't understand it. The songs were hidden amidst all that old people music (while my grandmother loved Nancy Sinatra's "These Boots Are Made For Walkin'," the music coming out of the Magnavox console stereo in our home was more likely Montovani and Ferrante and Teicher or 101 Strings' versions of Beethoven; and Days of Future Passed sounded more like that to me than the pop strains of Headquarters. And yet…

My brother got me In Seach of the Lost Chord for my birthday in 1968. I didn't want it, of course; he did, and he bought it in stereo so that I couldn't play it in my room and only on the Magnavox. (He got me Blood, Sweat and Tears too. Didn't want that either.) But I couldn't take my eyes off the cover, that hypnotizing painting by Phil Travers, who would work with the Moodys on six occasions. Like Hipgnosis' Storm Thorgerson and Pink Floyd, Travers was like another member of the band.

"I met the Moodys," he said, "in a London pub, and we worked out the details of the commission. They invited me down to the studio shortly after that first meeting to listen to the album. So I got an early taste for what they were doing. I liked it. And that's the way it always worked with them. I'd get to listen to the record, then discuss the themes and ideas behind it, before any art concepts were developed.

"The band wanted me to illustrate the concept of meditation. This was not something that I had much personal experience of, and so my early thoughts about the subject were, unfortunately, insubstantial. My first rough designs really reflected a lack of ideas. I began to panic a bit as time was running out, when that image I mentioned in the glass window, of a figure ascending, came back to me and everything then fell into place. I had days rather than weeks to complete the illustration, and submit it for approval. I used Gouache and some water colour to get the effect I was after."

Sometimes it’s the aesthetics of an LP that sparks our interest ( I can still visualize Nancy Sinatra in her go-go boots), and while we can argue over the validity of modern music (the tepid pop charts, the insufferable rap and its lack of musicality), one of the greatest losses that I've found since the advent of the CD and now MP3s and Spotify, is the disassociation of music with the visual. In the 60s, you wanted to peel that Velvet Underground banana or unzip Jagger's Levis, you had the Dark Side post cards on your bulletin board and you displayed Goodbye Yellow Brick Road like it was artwork, only to pick it up, open it and use the gatefold to roll a joint.

Sometimes it’s the aesthetics of an LP that sparks our interest ( I can still visualize Nancy Sinatra in her go-go boots), and while we can argue over the validity of modern music (the tepid pop charts, the insufferable rap and its lack of musicality), one of the greatest losses that I've found since the advent of the CD and now MP3s and Spotify, is the disassociation of music with the visual. In the 60s, you wanted to peel that Velvet Underground banana or unzip Jagger's Levis, you had the Dark Side post cards on your bulletin board and you displayed Goodbye Yellow Brick Road like it was artwork, only to pick it up, open it and use the gatefold to roll a joint.Anyway, it was a birthday present, but it was its cover that brought my attention to the highly overlooked Moodys. In retrospect, they'd done the symphony thing and pulled it off with flying colors, but this follow-up was 100% Moody Blues. Of the 33(!) different instruments used on the LP, each was played by the band. They earned the nickname of "the world's smallest symphony orchestra."

The LP is a journey, from beginning to end, in search of the chord and ephemeral whatnot. There is a heavy Eastern Philosophical influence, especially on the Mike Pinder contributions ("Best Way to Travel," "Om") and the tracks flow into each other seamlessly, making it one contiguous work of early world music. In every song, the singer yearns for something that cannot be defined. Mike Pinder's searing mellotron and Ray Thomas's soaring flute are the definitive sounds of the album, while the lyrics are a fanciful journey like Coleridge or Shelley.

The LP is a journey, from beginning to end, in search of the chord and ephemeral whatnot. There is a heavy Eastern Philosophical influence, especially on the Mike Pinder contributions ("Best Way to Travel," "Om") and the tracks flow into each other seamlessly, making it one contiguous work of early world music. In every song, the singer yearns for something that cannot be defined. Mike Pinder's searing mellotron and Ray Thomas's soaring flute are the definitive sounds of the album, while the lyrics are a fanciful journey like Coleridge or Shelley.Of course, this is the album that yielded two of the Moody's most enduring concert pieces, "Ride My See-saw" and the psychedelic "Legend of a Mind." Another standout is "The Actor," a Justin Hayward penned ballad so haunting it matches "Nights in White Satin." Then there's the lovely "Voices in the Sky," and John Lodge's epic, expermental "House of Four Doors," which samples musical styles throughout history. When I was 7, that one was key for me. Lost Chord is loaded with beautiful, experimental music. Why this band is so often overlooked, especially as a part of the Prog Rock era, I'll never know.

An aside: Other LPs bought because of their covers: the velvet wrapped Odessa, by the BeeGees, Brain Salad Surgery, Coltrane's Blue Train, Sinatra's In the Wee Small hours of the morning, Unknown Pleasures, Houses of the Holy, Captain Fantastic. Just a smattering.

Published on July 27, 2019 06:55

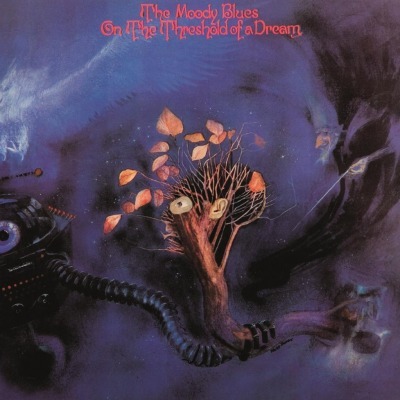

The Magnificent Moodies

It was fifty years ago that the Moody Blues released the third in a series of six phenomenal concept LPs that began with Days of Future Passed, still the iconic symphonic rock LP. Owning any of the six, particularly if you've never heard anything by the Moodies but "Nights in White Satin," is an experience you can thank me for later; well, thank them for.

The LP, On the Threshold of a Dream, was among the first wave of album-oriented rock or AOR that would take hold in the 1970s; indeed, On the Threshold of a Dream had no hit songs despite the LP being the first release to enter into the U.S. Top 20 and a No. 1 smash in the U.K.

The LP, On the Threshold of a Dream, was among the first wave of album-oriented rock or AOR that would take hold in the 1970s; indeed, On the Threshold of a Dream had no hit songs despite the LP being the first release to enter into the U.S. Top 20 and a No. 1 smash in the U.K.

In 1965, the Moody Blues had a hit with a remake of "Go Now" that was promo'd by what may be the very first MTV style video, predating even The Beatles' "Rain" and "Paperback Writer." Despite the single's success, the Moodies were struggling financially. Decca Records, hoping to further its exploration into stereophonic recordings, asked the band to do a rock interpretation of Dvorak's New World Symphony (Symphony No. 9) for the new Deram Records label. Instead the band recorded, without the label's knowledge, Days of Future Passed with Mike Pinder's "Dawn is a Feeling" as the catalyst for the project. Justin Heyward would follow with the LP's big hit, "Nights in White Satin," a play on words in which bed sheets are used as a cunning metaphor. Released in 1966, it is still my favorite Moody Blues LP and it introduced the world to symphonic interpretations of rock music.

The band would follow up with In Search of the Lost Chord, a psychedelic concept piece all about the journey. It contained no real hit but gained a lot of radio play with "Ride My See-Saw" and the biopic fantasy "Legend of a Mind," about Dr. Timothy Leary. The song is a part of an extended concept song called "The House of Four Doors," the Moodies at their finest and an incredible soiree into the psychedelic experience.

With the 3rd LP in the concept series, Threshold of a Dream, the Moodies would fully establish themselves as the first AOL rock band. Each of the LPs was meant to be listened to in its entirety; this wasn't background music. The Moody Blues were when listeners first sat on the couch and immersed themselves in the experience. What's interesting though, is that with the next few LPs, the Moodies would have their biggest hits in "Question," "The Story in Your Eyes," "I'm Just a Singer in a Rock 'n' Roll Band" and oddly, six years after its initial release, "Nights in White Satin" would make it all the way to No. 1.

On the Threshold of a Dream is an LP oozing with splash and psychedelic experimentation. The album was a runaway smash in the U.K. and provided The Moody Blues with their first No. 1 British LP, remaining on the charts for some 70 weeks.

The LP, On the Threshold of a Dream, was among the first wave of album-oriented rock or AOR that would take hold in the 1970s; indeed, On the Threshold of a Dream had no hit songs despite the LP being the first release to enter into the U.S. Top 20 and a No. 1 smash in the U.K.

The LP, On the Threshold of a Dream, was among the first wave of album-oriented rock or AOR that would take hold in the 1970s; indeed, On the Threshold of a Dream had no hit songs despite the LP being the first release to enter into the U.S. Top 20 and a No. 1 smash in the U.K. In 1965, the Moody Blues had a hit with a remake of "Go Now" that was promo'd by what may be the very first MTV style video, predating even The Beatles' "Rain" and "Paperback Writer." Despite the single's success, the Moodies were struggling financially. Decca Records, hoping to further its exploration into stereophonic recordings, asked the band to do a rock interpretation of Dvorak's New World Symphony (Symphony No. 9) for the new Deram Records label. Instead the band recorded, without the label's knowledge, Days of Future Passed with Mike Pinder's "Dawn is a Feeling" as the catalyst for the project. Justin Heyward would follow with the LP's big hit, "Nights in White Satin," a play on words in which bed sheets are used as a cunning metaphor. Released in 1966, it is still my favorite Moody Blues LP and it introduced the world to symphonic interpretations of rock music.

The band would follow up with In Search of the Lost Chord, a psychedelic concept piece all about the journey. It contained no real hit but gained a lot of radio play with "Ride My See-Saw" and the biopic fantasy "Legend of a Mind," about Dr. Timothy Leary. The song is a part of an extended concept song called "The House of Four Doors," the Moodies at their finest and an incredible soiree into the psychedelic experience.

With the 3rd LP in the concept series, Threshold of a Dream, the Moodies would fully establish themselves as the first AOL rock band. Each of the LPs was meant to be listened to in its entirety; this wasn't background music. The Moody Blues were when listeners first sat on the couch and immersed themselves in the experience. What's interesting though, is that with the next few LPs, the Moodies would have their biggest hits in "Question," "The Story in Your Eyes," "I'm Just a Singer in a Rock 'n' Roll Band" and oddly, six years after its initial release, "Nights in White Satin" would make it all the way to No. 1.

On the Threshold of a Dream is an LP oozing with splash and psychedelic experimentation. The album was a runaway smash in the U.K. and provided The Moody Blues with their first No. 1 British LP, remaining on the charts for some 70 weeks.

Published on July 27, 2019 06:53

July 16, 2019

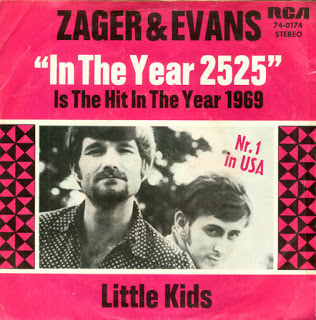

2525

There has been many a nihilistic tune in the rock era and yet, the bleakest song ever to hit No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100 remains Zager and Evans' "In the Year 2525" which questions whether humanity will even survive.

There has been many a nihilistic tune in the rock era and yet, the bleakest song ever to hit No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100 remains Zager and Evans' "In the Year 2525" which questions whether humanity will even survive. Denny Zager and Rick Evans' "In the Year 2525 (Exordium & Terminus)" was written by Evans in 1964, recorded in 1968 and released on Truth Records, then was picked up by RCA to become the top hit in the nation as man walked on the moon for the first time. It remained at No. 1 as Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins returned to earth, as Charles Manson's Family unleashed their evil on the Hollywood Hills, and only dropped out of the top slot as Woodstock was wrapping up.

Evans' chorus-free composition, unlike many starry-eyed, flower-power anthems of the day, didn't redeem mankind in a cautionary epilogue, and instead for the year 5555, they sang, "Your arms hangin' limp at your sides/ Your legs got nothin' to do/ Some machine's doin' that for you." And in another thousand years, test-tube babies would be the norm. Homo sapiens, having come to rely on pills and automation where once there was imagination and self-determination, would become no more substantial than furniture.

"In the Year 2525" was a far cry from a song it kept from the No. 1 spot, Oliver's "Good Morning Starshine" from the musical Hair, a song so saccharine sweet that its chorus included the line, "Gliddy glub gloopy, nibby nabby noopy la, la, la, lo, lo/ Sabba sibby sabba, nooby abba nabba, le, le, lo, lo." I include it in its entirety since so many of us sing it incorrectly - you gotta get your nonsense right, folks.

Published on July 16, 2019 12:01

na

Four and a half years after they first appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show and charmed teenie-boomers with their yeah yeah yeahs, The Beatles released "Hey Jude," a revolutionary and mature track far removed from the mop tops' early work, even if it utters the word "na" 240 times.By 1968 the Fab Four's Edwardian suits were long gone, as was the notion that they were simply the flavor-of-the-month. The Beatles ditched live concerts to experiment in the studio, and while they didn't have a stranglehold on the Billboard charts as they did in 1964 (when at one point they had the top five hits), their music remained wildly popular."Hey Jude," like "She Loves You," is the story of a friend offering advice, but the world, as well as the music, had grown more complex. Paul McCartney has said he wrote it to cheer up Julian Lennon, John's five-year-old son, when Lennon was divorcing his first wife. The narrator realizes that things may not be good now, but with a little work he can find his true love "and make it better." "Hey Jude" was still on the radio rotation in July of 1969, having been the biggest selling single of 1968 and reaching out to top the list again in 1969.

Four and a half years after they first appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show and charmed teenie-boomers with their yeah yeah yeahs, The Beatles released "Hey Jude," a revolutionary and mature track far removed from the mop tops' early work, even if it utters the word "na" 240 times.By 1968 the Fab Four's Edwardian suits were long gone, as was the notion that they were simply the flavor-of-the-month. The Beatles ditched live concerts to experiment in the studio, and while they didn't have a stranglehold on the Billboard charts as they did in 1964 (when at one point they had the top five hits), their music remained wildly popular."Hey Jude," like "She Loves You," is the story of a friend offering advice, but the world, as well as the music, had grown more complex. Paul McCartney has said he wrote it to cheer up Julian Lennon, John's five-year-old son, when Lennon was divorcing his first wife. The narrator realizes that things may not be good now, but with a little work he can find his true love "and make it better." "Hey Jude" was still on the radio rotation in July of 1969, having been the biggest selling single of 1968 and reaching out to top the list again in 1969.

Published on July 16, 2019 09:44

July 11, 2019

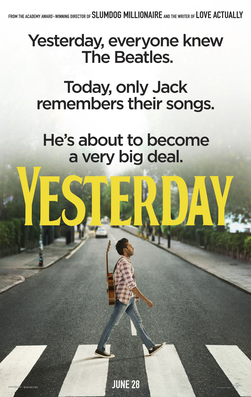

Yesterday

The premise of the film Yesterday is that the Beatles catalog is unknown to everyone except a young musician who takes the songs and re-creates them, of course making them famous once again. I'll leave the analysis of the film to the critics, they've beat it up enough already, but here's my thought: if I had the Beatles' catalog at my disposal, would there be songs that I would just let go, that I would allow to disappear into the ether? I know it's sacred territory to tread on, but just for a moment, think about which five songs you would leave out of the Beatles' canon. In the meantime these are mine.

The premise of the film Yesterday is that the Beatles catalog is unknown to everyone except a young musician who takes the songs and re-creates them, of course making them famous once again. I'll leave the analysis of the film to the critics, they've beat it up enough already, but here's my thought: if I had the Beatles' catalog at my disposal, would there be songs that I would just let go, that I would allow to disappear into the ether? I know it's sacred territory to tread on, but just for a moment, think about which five songs you would leave out of the Beatles' canon. In the meantime these are mine.There's so much discussion about whittling down The White Album to just a single desk. Although there are songs indeed that I would remove, in particular, "Don't Pass Me By," I've long defended songs like "Honey Pie" and "Why Don't We Do It in the Road." Indeed, Paul's "road song" is a poetic endeavor that utilizes repetition in a way that, well, doing it in the road utilizes repetition. It really is a case when linguistics, grammar and poetry all come together as one, like it or not. And "Honey Pie" is the kind of filler that the album needs to string one song to the next to give it continuity, even if it doesn't work well on its own. And yet it does work poetically, and it's one of those songs that if you get it stuck in your head, at least you know all the words

"Don't Pass Me By," on the other hand, is among my least favorite songs in the Beatles canon, and if it were just to disappear I'd feel fine. On Family Guy, Paul takes a song by Ringo and hangs it on the refrigerator, as if it were a drawing by a child. And childish it is, out of place on the LP at best. I skip it every time.

On that note, the most skipped song on any Beatles album is George Harrison's "Within You Without You" from Sgt. Pepper. But dismissing the track as a production masterpiece, as one of the pinnacle songs in the psychedelic era, is naïve at best. It's a beautiful song that brilliantly comingles east and west and if you're one of the skippers, you really need to meditate on this.

Now, as much as I've defended "Honey Pie" as an integral component of The White Album, if indeed filler, I find Phil Spector's butchering of the already diluted song "Dig It" to be filler and nothing more, I wouldn't even consider it a part of the Beatles' canon; it's just there like that parsley sprig on your plate at Denny's.

In my younger days, I would've been quick to dismiss McCartney's children songs like "Life Goes on" or even "Yellow Submarine," and yet as an adult, I sang these songs to my children. That, in turn, led to their finding "Uncle Albert/Admiral Halsey" on their own and ultimately creating Beatle Fans. Still, I have to include "All Together Now" as drivel. I'm not saying it's not catchy, but so is the flu.

I won't include any of the cover songs like "Boys" or "Honey Don't" because the artists who originally created those songs would have still existed in the Yesterday universe, but the penultimate track on my list, and I don't think I'm alone in saying this, Revolution No. 9. It may hold a certain significance in terms of fiddling with tape loops in an avant-garde way - oh never mind it’s terrible. I'd probably find it interesting on a collection of outtakes, but it muddies The White Album at best, only is topped by only one song, and yes, at least this one's a song: "You Know My Name, Look Up the Number." Just more studio play, but here it sounds frustrated and emotionally drained, And despite some interesting production values, nothing can save this sinking ship of a song. I had a DJ friend who at the end of the night at a club in LA, the Seven Seas to be exact, who would play this track just to clear the room at 2am.

I pride myself on only reporting the positives in rock 'n' roll, and so to put a spin on this, I want you to imagine the perfect Beatles catalog, and honestly, taking out those five songs brings us that much closer.

Published on July 11, 2019 14:04

Rock Lyrics as Poetry

A colleague asked another for his favorite poem (we are an eclectic collection of English teachers, mind you). My colleague’s fave is "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock," and immediately upon his admission of the T.S. (that's Tough Shit) Eliot tome, I blurted out, as a fellow English teacher will do: "I have measured out my life in coffee spoons." Though hardly lighthearted, "Prufrock" is one of Eliot's most accessible poems (aside from Cats), a far cry from the preposterously sullen The Waste Land, his most critically acclaimed work. I would agree that "Prufrock" is an astute choice.

A colleague asked another for his favorite poem (we are an eclectic collection of English teachers, mind you). My colleague’s fave is "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock," and immediately upon his admission of the T.S. (that's Tough Shit) Eliot tome, I blurted out, as a fellow English teacher will do: "I have measured out my life in coffee spoons." Though hardly lighthearted, "Prufrock" is one of Eliot's most accessible poems (aside from Cats), a far cry from the preposterously sullen The Waste Land, his most critically acclaimed work. I would agree that "Prufrock" is an astute choice.The other teacher's response to the question was "Sounds of Silence." I forget the word my colleague used to describe the choice; pedantic, maybe, or sophomoric. His response to me was that no rock lyric could rate beside Eliot or Dylan Thomas, et al. Despite his opinionated brilliance, I couldn't disagree with him more. I took the defense of the other teacher to heart, quoting Springsteen, "The screen door slams,/ Mary's dress waves./ Like a vision she dances across the floor as the radio plays/ Roy Orbison singing, 'For the Lonely.'" Eliot, the disenfranchised American from Ohio, may indeed expertly capture the Brit soul, but "Thunder Road" is pure Americana, and like "Prufrock," plays with words and phrasing in an equally stylistic manner. The subtle rhyme, the enjambment within the lines making "as the radio plays" an American expression of incidental background music in general, but then, in the next line peppering the small town feel with Roy Orbison's iconic single, is genius.

My colleague's view is that it's always the music, and not the lyrics that provide the greater emotional impact, and yet the phatic is common to both song lyrics and poetry; music aids the lyric, condemning it to be not quite poetry – forever – while poetry is its own pseudo music, damning it to a netherworld without melody. That in mind, maybe the choice of "Sounds of Silence" is indeed pedantic. The lyrics themselves sophomoric; one might call it kitsch. It’s not Simon's strongest lyric by any means, but that doesn’t discount Simon. From his play with John Donne in "I am a Rock," dismissing Donne’s ideology that no man is an island, to the sublime "America," which, like "Thunder Road" captures American Youth in its most restless, the twenty-five-year-old Simon was equal at least to the worst of Dylan Thomas, himself a drunken rock star, and rivals at times Thomas at his most okay, that “second chair” that Thomas, based on his alcohol distraction, sat in on many occasions.

My colleague's view is that it's always the music, and not the lyrics that provide the greater emotional impact, and yet the phatic is common to both song lyrics and poetry; music aids the lyric, condemning it to be not quite poetry – forever – while poetry is its own pseudo music, damning it to a netherworld without melody. That in mind, maybe the choice of "Sounds of Silence" is indeed pedantic. The lyrics themselves sophomoric; one might call it kitsch. It’s not Simon's strongest lyric by any means, but that doesn’t discount Simon. From his play with John Donne in "I am a Rock," dismissing Donne’s ideology that no man is an island, to the sublime "America," which, like "Thunder Road" captures American Youth in its most restless, the twenty-five-year-old Simon was equal at least to the worst of Dylan Thomas, himself a drunken rock star, and rivals at times Thomas at his most okay, that “second chair” that Thomas, based on his alcohol distraction, sat in on many occasions. The songwriter who captures best the idea of the poet is Bob Dylan (whose name, of course, comes from Dylan Thomas). Dylan is such an idiosyncratic genius that it's perilous to imitate him; his faults, at worst annoying, at best invigorating, ruin lesser talents. But contrary to the mythology (and to the Nobel Prize), the man did not revolutionize modern poetry, American folk, popular music, or the whole of modern thought; and the Village Voice, prattling on about "new plateaus for poetic, content-conscious songwriters" and "the bastard child of Chaplin, Celine and Hart Crane," is nothing, if not ludicrous. However inoffensive (at worst) or haunting (at best) "The ghost of electricity howls in the bones of her face" sounds on vinyl, it's plain silly without the music. Conversely, "My Back Pages" is a bad poem, though it's a great song with an unforgettable refrain. Music softens our demands, the importance of what is being said somehow overbalances the flaws, and Dylan's delivery adds an edge not present in the words. Add to that the premise that if the words don't work, one can always mumble, and you've realized the perfect formula. (That said, when Dylan won the Nobel Prize every poet and novelist in the world, myself included, threw up a little in his mouth. I mean really? Solzhenitsyn, Steinbeck, Kipling, Hemingway, Camus, Faulkner, Eliot, Churchill?)

In the same vein, The Mamas and Papas are full of diversions: contrapuntal arrangements, orchestral improvisations, odd rhyme schemes and John Phillips' trick of drawing out words with repetitions and pauses. In songs like "California Dreamin'," "12:30" and so many others, Phillips is obviously a good lyricist, though his lyrics are rarely easy to understand. I wonder how many are aware that "Strange Young Girls" is about LSD. No secret about it; it's right there out in the open in the first stanza: "Walking the Strip, sweet, soft, and placid/ Off'ring their youth on the altar of acid." But no one notices because there's so much within the song’s stellar arrangement. On a crude level, this vagary permits the kind of one-to-one symbolism of pot songs like "Along Comes Mary."

In the same vein, The Mamas and Papas are full of diversions: contrapuntal arrangements, orchestral improvisations, odd rhyme schemes and John Phillips' trick of drawing out words with repetitions and pauses. In songs like "California Dreamin'," "12:30" and so many others, Phillips is obviously a good lyricist, though his lyrics are rarely easy to understand. I wonder how many are aware that "Strange Young Girls" is about LSD. No secret about it; it's right there out in the open in the first stanza: "Walking the Strip, sweet, soft, and placid/ Off'ring their youth on the altar of acid." But no one notices because there's so much within the song’s stellar arrangement. On a crude level, this vagary permits the kind of one-to-one symbolism of pot songs like "Along Comes Mary." All this in mind, one is indeed hard-pressed to take a stance for rock music as poetry. Morrison’s "The End" is pedantic, to use my colleague's words, and The Police's "Don't Stand So Close to Me," sophomoric. But I can indeed go back to Simon: "What a dream I had… Pressed in organdy/ Clothed in crinoline of smoky burgundy/ Softer than the rain/ I wandered empty streets down past the shop displays/ I heard cathedral bells tripping down the alleyways/ As I walked on…" It’s Simon but it could be Shelley; alter the demeanor or the known cadence, it could be Emily Dickenson.

I don't even have to say a thing about Sincerely, L. Cohen's "Famous Blue Raincoat": "It's four in the morning, the end of December/ I'm writing you now just to see if you're better/ New York is cold, but I like where I'm living/ There's music on Clinton Street all through the evening. - I hear that you're building your little house deep in the desert/ You're living for nothing now, I hope you're keeping some kind of record. - Yes, and Jane came by with a lock of your hair/ She said that you gave it to her/ That night that you planned to go clear./ Did you ever go clear?

I don't even have to say a thing about Sincerely, L. Cohen's "Famous Blue Raincoat": "It's four in the morning, the end of December/ I'm writing you now just to see if you're better/ New York is cold, but I like where I'm living/ There's music on Clinton Street all through the evening. - I hear that you're building your little house deep in the desert/ You're living for nothing now, I hope you're keeping some kind of record. - Yes, and Jane came by with a lock of your hair/ She said that you gave it to her/ That night that you planned to go clear./ Did you ever go clear?Tom Waits wrote "Tom Traubert's Blues" after visiting Skid Row in Los Angeles, drinking a pint of rye and throwing up: "Wasted and wounded, it ain't what the moon did, I've got what I paid for now/ See you tomorrow, hey Frank, can I borrow a couple of bucks from you/ To go waltzing Mathilda, waltzing Mathilda,/ You'll go waltzing Mathilda with me." It’s Bukowski, that (but does it fly without the Aussie nursery rhyme?).

For simplicity through repetition on the basic human desire, maybe McCartney did it best: "Why don't we do it in the road?/ Why don't we do it in the road?/ Why don't we do it in the road?/ Why don't we do it in the road?/ No one will be watching us,/ Why don't we do it in the road?" It's Twain simplicity and honesty, and daring for the 60s, with the next progression of theme and style going to Anthony Kiedis of Red Hot Chili Peppers: "Let me shine your diamond/ The girl got a scratch/ Slap that cat/ Have mercy - I want to party on your pussy, baby/ I want to party on, party on your pussy/ I want to party on your pussy, baby/ I want to party on your pussy, yeah, yeah, yeah."

From Joni Mitchell's Blue to Dark Side of the Moon, the poetry is there, often hidden within the music or the arrangements; what an unfair advantage. Poetry without it is a dying art. Ho-hum. I guess we will be seeing a lot more Dylans joining the 113 recipients of the Nobel (hopefully there are budding Plaths and Cummings out there to prove me wrong). In the meantime: "My head is my only house unless it rains." Yep, sheer poetry.

My favorite rock lyrics? Fleetwood Mac's "Landslide." I have no delusions about Nicks' lyrics vs. any "great" poetry, but the question was my favorite lyrics; not the greatest. My favorite poem, btw? "Shake and shake the ketchup bottle,/ None'll come and then a lot'll."

Published on July 11, 2019 13:41

On Music and Poetry

We settle into a seat on a train, at times forgetting the destination, enjoying the ride of its own accord. The train is its own world, even as it moves with purpose; if the train broke down, we'd be annoyed - the purpose of the train slips our minds only fleetingly - yet it allows us in its mesmerizing clickity-clack to forget the reason for the journey and to simply enjoy the experience. Expression is like this, too. We talk for a reason, and yet we also just enjoy talking. Poetry then is reticent expressiveness; it combines the enjoyable and the purposeful aspects of the train ride; at times rambling on, clickity-clackiting; at times direct and purposeful.

1968 features prominently in the music-as-poetry construct, a time which, artistically, happily, resembles the Romantic era: sensual and intellectual, though not overly so, and, because indulgence was miraculously tempered by a certain unstated restraint, popular. In the last post, we touched on the debate between poetry and lyrics: while music aids the lyric, condemning it to be not quite poetry, poetry is its own music, condemning it to be naked, without music, forever. I don't know which I feel sorrier for. Some will say the two can never be reconciled. Madness and torture! Why do they exist, never to meet! Poetry and music! Divided heart! Divided mind! Poor, divided mankind! (Dramatic, huh?)

Oh, poppycock, of course, they do; they meet and have an illicit affair, and if an especially beautiful melody accompanies the words of a particular lyric, making the words even more lovely, do we assume the words are responsible or has the music inspired the words?

For the research here, I found myself in realism-mode, the Brönte factor, and in its simplicity and constructive realism, adding in a dose of repetition to make Mark Twain proud, I chose McCartney's aforementioned "Why Don't We Do It In the Road."

Love it or hate it, celebrate it or be embarrassed by it, "Why Don't We Do It In The Road?" showed that the Fab Four were more than peace, love and flowers (or is the song the essence of the hippie trinity?). Some might call it bold (particularly from McCartney), yet something like this had to be expected, especially on an album with a plain white cover, as if something subversive was inside. After the furor caused by John's "We're bigger than Jesus" statement, and the banned songs by the BBC due to drug references, not to mention John and Yoko's full frontal on the cover of Two Virgins, why not compose a song about the most absurdly taboo subject imaginable and see how many feathers could be ruffled?

"The idea behind 'Why Don't We Do It In The Road' came from something I'd seen in Rishikesh," Paul explained. "I was up on the flat roof meditating and I'd seen a troupe of monkeys walking along in the jungle and a male just hopped on to the back of this female and gave her one, as they say in the vernacular. Within two or three seconds he hopped off again, and looked around as if to say, 'It wasn't me,' and she looked around as if there had been some mild disturbance but thought, 'Huh, I must have imagined it,' and she wandered off.

"And I thought, 'Bloody hell, that puts it all into a cocked hat.' That's how simple the act of procreation is, this bloody monkey just hopping on and hopping off. There is an urge, they do it, and it's done with. And it's that simple. We have horrendous problems with it, and yet animals don't.” While Paul’s account makes it simply rudimentary, it also takes out the romance. Frankly, doesn't the song express our basic instincts, not just in a physical manner, indeed in this respect we’re like animals, but in an obliquely human way as well: "WDWDIITR" is all about the romance of lust. How Byronic is that?

So, back to the train. Monkeys just do it in the road. We take our time. We get on a train. We sit together and chat, forget about the ride, forget about the destination; it's all, at least for now, about the journey. And yet, in the nuance of the encounter, you contemplate her smile, the fullness of her breasts, his scruffy cool, and in your mind you just want to push him/her up against... Those thoughts wind through your mind, come and go, the question building, insistent, louder and louder. First, it's a question; then it's a plea:

Why don't we do it in the road?No one will be watching us

Why don't we do it in the road?

Published on July 11, 2019 12:17