R.J. Stowell's Blog: rjsomeone, page 21

August 3, 2020

Why Vinyl Sounds Better

When the battle ensues, professed audiophiles understand, or should, why old vinyl sounds so much better than CDs or mp3s. It doesn't have to, by the way, but it does. And that's not opinion, it's a sonic fact. Enter loudness and what is referred to as the "Loudness War."

With the advent of the CD, the loudness war began, essentially maxing out and pushing beyond the medium’s ability through what is called "compression" (codec). I'll skip the mumbo jumbo and simplify it: Let's say you have an oboe soloist in your living room. The sonic experience would fill the room. Now, instead, your oboist is accompanied by an amplified guitar. The guitar would simply drown out the oboe. Compression through digital media pushes the sound of the oboe so that it equals that of the guitar. Now you can hear both equally but lose all nuance.

The LP that comes to mind first is the AM10 In the Court of the Crimson King by King Crimson. The track "I Talk to the Wind" begins so imperceptibly that one almost strains to hear it. The production is done to contrast what's next. The LP is meant to be an experience, one of contrasts and extremes. If you grew up with the CD, you wouldn't know that.

For his remixes of classic progressive LPs, Steven Wilson undid the CD's sordid contribution to the Loudness War and reestablished that tonal distinction. Should one listen to the remix vs. the original vinyl, the difference is slight. There's a tad more brilliance and separation of harmonies, but each of the remixes remains true to the original. It's when the remixes are compared to the over-compressed CD versions of the 90s (or worse, the mp3s) that the real difference is clear. For more detailed looks into the Loudness Wars, check out the web or YouTube. I'd recommend instead that you just dive into the analog experience. If you've never heard classics LPs on anything but a CD or on an mp3, you're in for a fabulous experience.

For his remixes of classic progressive LPs, Steven Wilson undid the CD's sordid contribution to the Loudness War and reestablished that tonal distinction. Should one listen to the remix vs. the original vinyl, the difference is slight. There's a tad more brilliance and separation of harmonies, but each of the remixes remains true to the original. It's when the remixes are compared to the over-compressed CD versions of the 90s (or worse, the mp3s) that the real difference is clear. For more detailed looks into the Loudness Wars, check out the web or YouTube. I'd recommend instead that you just dive into the analog experience. If you've never heard classics LPs on anything but a CD or on an mp3, you're in for a fabulous experience.The hero in all of this, particularly for those who enjoy classic progressive rock like Tull and Yes and Gentle Giant, is Steven Wilson. Known most specifically as the frontman of Porcupine Tree, his solo work is not to be missed. Here, though, his latest release, is something completely different. Call it Steven Wilson EDM – it certainly didn't make the critics happy when it was released in March – but I can't stop listening.

"Where 2017’s To the Bone confronted the emerging global issues of post-truth and fake news, The Future Bites places the listener in a world of 21st-century addictions. It’s a place where ongoing, very public experiments constantly take place into the affects of nascent technology on our lives. From out of control retail therapy, manipulative social media and the loss of individuality, The Future Bites is less a bleak vision of an approaching dystopia, more a curious reading of the here and now."

In total to date, Wilson has remixed 53 classic prog LPs including the most important albums from Yes, Jethro Tull and even Chicago II.

Published on August 03, 2020 04:54

July 28, 2020

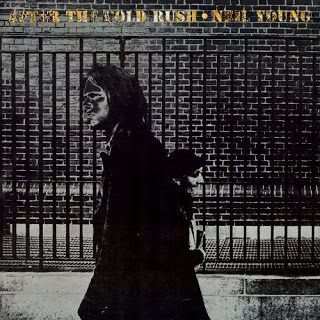

After the Gold Rush - 50 Years Ago

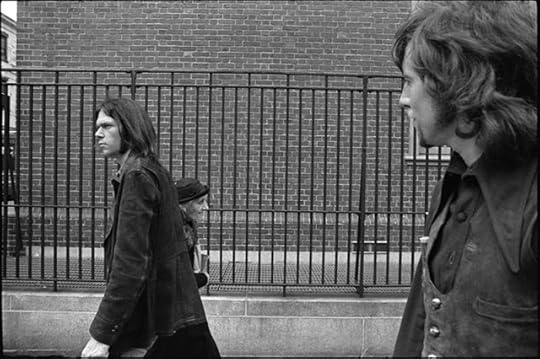

I was in my teens and caught a ride to the record shop to buy Harvest, the new release by Neil Young. In the parking lot, Pamela D. and I sat waiting as "Heart of Gold" played on the radio. The record shop was out of it, and I bought After the Gold Rush (AM9). Harvest, of course is classic, main stream America's introduction to Neil Young, but good fortune and brisk sales had me plop down $3.77 for Gold Rush. It was the best $3.77 I ever spent. By the release of the LP in '71, Young had already shined in the rosters of two legendary bands (Buffalo Springfield and Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young), embarked on a premature 1969 self-entitled solo debut and collaborated with the garage rock band, Crazy Horse on Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere. Ripe for a flourishing solo career, the finely-crafted After the Gold Rush defined the musical persona that would make Young a legend. Young's primary role was always that of a sweet, sentimental folky, and on After the Gold Rush, Young dishes out downbeat reflection ("Tell Me Why," "Don't Let It Bring You Down"), rainy, country rock ("Oh, Lonesome Me," "Cripple Creek Ferry") and gorgeous odes of encouragement ("I Believe In You," "Birds"), all encased in golden acoustic guitar and painted in Young's masterful use of imagery ("Old man lying by the side of the road/ With the lorries rolling by/ Blue moon sinking from the weight of the load/ And the buildings scrape the sky/ Cold wind ripping down the allay at dawn/ And the morning paper flies/ Dead man lying by the side of the road/ With the daylight in his eyes"). But After the Gold Rush revealed another quintessential truth about Young's psyche: this gentle singer/songwriter had a streak of embittered social conscious (the title track, the dead-on "Southern Man") and a flair for lumbering guitar rock ("When You Dance You Can Really Love," "Southern Man"). After the Gold Rush is the sound of inspiration arriving, doors cracking open and an artist being baptized.

I was in my teens and caught a ride to the record shop to buy Harvest, the new release by Neil Young. In the parking lot, Pamela D. and I sat waiting as "Heart of Gold" played on the radio. The record shop was out of it, and I bought After the Gold Rush (AM9). Harvest, of course is classic, main stream America's introduction to Neil Young, but good fortune and brisk sales had me plop down $3.77 for Gold Rush. It was the best $3.77 I ever spent. By the release of the LP in '71, Young had already shined in the rosters of two legendary bands (Buffalo Springfield and Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young), embarked on a premature 1969 self-entitled solo debut and collaborated with the garage rock band, Crazy Horse on Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere. Ripe for a flourishing solo career, the finely-crafted After the Gold Rush defined the musical persona that would make Young a legend. Young's primary role was always that of a sweet, sentimental folky, and on After the Gold Rush, Young dishes out downbeat reflection ("Tell Me Why," "Don't Let It Bring You Down"), rainy, country rock ("Oh, Lonesome Me," "Cripple Creek Ferry") and gorgeous odes of encouragement ("I Believe In You," "Birds"), all encased in golden acoustic guitar and painted in Young's masterful use of imagery ("Old man lying by the side of the road/ With the lorries rolling by/ Blue moon sinking from the weight of the load/ And the buildings scrape the sky/ Cold wind ripping down the allay at dawn/ And the morning paper flies/ Dead man lying by the side of the road/ With the daylight in his eyes"). But After the Gold Rush revealed another quintessential truth about Young's psyche: this gentle singer/songwriter had a streak of embittered social conscious (the title track, the dead-on "Southern Man") and a flair for lumbering guitar rock ("When You Dance You Can Really Love," "Southern Man"). After the Gold Rush is the sound of inspiration arriving, doors cracking open and an artist being baptized.And it was all dumb luck. In January 1969, 23-year-old Neil Young released his self-titled solo debut album, its layers of guitars reminiscent of his work with the Buffalo Springfield. But when Young failed to crack the album charts, he immediately went back to work, recording Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere at Wally Heider's in less than two weeks with new backing band Crazy Horse.

His association with Crosby, Stills and Nash left Young poised for stardom as he made plans to cut a third solo album in early 1970. Anyone else would've played it safe, but Young followed his instincts. "At that point, I didn’t like seeing other musicians in the hallways," Young told writer Jimmy McDonough. "I didn't like hearing other music. I just wanted to be by myself."

Young set up shop in the basement of his Topanga Canyon home. He paneled the walls with pine milled from the trees in his backyard. Neil's modest gear collection included a Scully 8-track, a small mixer, and a handful of mics. Because there was no room for echo plates or other processors, the sound would be unusually arid with all the vocals cut live and dry. "There was a shitload of room on those recordings," recalled Young, " because there wasn’t anything else goin' on. Just rhythm guitar, bass and drums - that's all there was. The song was it, and everything else was supporting it."

Young set up shop in the basement of his Topanga Canyon home. He paneled the walls with pine milled from the trees in his backyard. Neil's modest gear collection included a Scully 8-track, a small mixer, and a handful of mics. Because there was no room for echo plates or other processors, the sound would be unusually arid with all the vocals cut live and dry. "There was a shitload of room on those recordings," recalled Young, " because there wasn’t anything else goin' on. Just rhythm guitar, bass and drums - that's all there was. The song was it, and everything else was supporting it."As CSNY's Déjà Vu landed in stores that March, Young went to work in his makeshift studio, backed by a skeleton crew that included Crazy Horse drummer Ralph Molina and CSNY bassist Greg Reeves. Also on hand was guitarist Nils Lofgren, a Washington, D.C. native who'd barged into Young's dressing room months earlier and brazenly performed a few originals on Young's Martin D-45. Impressed, Young rang up the teenager and asked if he’d join him in the studio for the making of the new album. "I get there, and right away, Neil hands me an old Martin D-18 and has me play the second guitar part on 'Tell Me Why,'" recalls Lofgren. "Which was actually the first time I'd ever done any real acoustic-guitar work. At the end of the session, he gives me the guitar as a gift for helping him make the record. I was 18, I went running off a mile into the deep woods of Topanga Canyon, got lost and just sat there with this gorgeous guitar, thrilled out of my mind that Neil Young had just given me his Martin to keep. Totally in the clouds." Lofgren's inexperience was key to the LP's minimalism.

Young got even more minimalism out of Jack Nitzsche, who'd worked with Young during his days with the Buffalo Springfield. Nitzsche and Crazy Horse convened in the basement and cut "When You Dance I Can Really Love" totally live, with Young flailing away on his Gretsch White Falcon.

It's this raw emotion and the straightforward approach that sets apart After the Gold Rush, which was released in late summer to unanimous acclaim; by Christmas, it had become Young’s first Top 10 album, and remained on the charts for over a year on its way to selling two million copies. Though a stunning success, Young's decision to bring it all back home would take its toll on his personal life. "I was writing ‘Southern Man’ in the studio," and [wife] Susan was angry at me for some reason, throwing things; they were crashing against the door." The same month the album was released, Young's already fractured first marriage officially came to a close; you can hear it in the vocals and in each riff. Like Joni on Ladies, or like Leonard Cohen, Neil Young had become the consummate singer songwriter.

Published on July 28, 2020 04:45

July 26, 2020

am@random – Something You Haven’t Heard Of – And May Not Want To

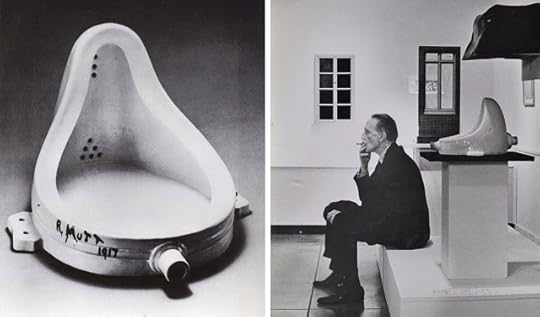

The Dada-ist, or anti-art, Movement began with Marcel Duchamp in the 1920s. The Philadelphia Museum of Art is fortunate to have one of the world’s greatest collection of the “anti-artist." His most famous work was meant to be viewed in a much different manner than it has been these past 100 years. The glasswork piece, “The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even,” 1915-23, was set for installation in the museum’s north wing façade when the fragile work was smashed into little pieces. In a Kintsugi manner, Duchamp spent four years piecing the work back together. More controversial, though, is Duchamp’s "found object, “Fountain,” one his “readymade” pieces, was simply a urinal purchased from the J. L. Mott Iron Works, 118 Fifth Avenue, N.Y. The artist brought the urinal to his studio at 33 West 67th Street and signed the porcelain, "R. Mutt 1917.” Despite its prominence at PMA, there are many who question whether the piece is art or not. I won’t argue that here.Instead, I bring to your attention the non-music, Plunderphonics. Essentially created by British artist John Osborne, and explained in an essay titled, “Plunderphonics, or Audio Piracy as a Compositional Prerogative.” The short of it: Plunderphonics is the musical equivalent of Duchamp’s "found" object art (hence "plunder"). Plunderphonics is “any music made by taking one or more existing audio recordings and altering them in some way to make a new composition;” essentially, sampling to the nth degree. Kirby’s work is exhausting, utilizing in his recordings thousands of sampled – i.e. plagiarized – sounds from known works. The samples are left as snippets, sped up or slowed down.

The Dada-ist, or anti-art, Movement began with Marcel Duchamp in the 1920s. The Philadelphia Museum of Art is fortunate to have one of the world’s greatest collection of the “anti-artist." His most famous work was meant to be viewed in a much different manner than it has been these past 100 years. The glasswork piece, “The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even,” 1915-23, was set for installation in the museum’s north wing façade when the fragile work was smashed into little pieces. In a Kintsugi manner, Duchamp spent four years piecing the work back together. More controversial, though, is Duchamp’s "found object, “Fountain,” one his “readymade” pieces, was simply a urinal purchased from the J. L. Mott Iron Works, 118 Fifth Avenue, N.Y. The artist brought the urinal to his studio at 33 West 67th Street and signed the porcelain, "R. Mutt 1917.” Despite its prominence at PMA, there are many who question whether the piece is art or not. I won’t argue that here.Instead, I bring to your attention the non-music, Plunderphonics. Essentially created by British artist John Osborne, and explained in an essay titled, “Plunderphonics, or Audio Piracy as a Compositional Prerogative.” The short of it: Plunderphonics is the musical equivalent of Duchamp’s "found" object art (hence "plunder"). Plunderphonics is “any music made by taking one or more existing audio recordings and altering them in some way to make a new composition;” essentially, sampling to the nth degree. Kirby’s work is exhausting, utilizing in his recordings thousands of sampled – i.e. plagiarized – sounds from known works. The samples are left as snippets, sped up or slowed down.

Here, I have to take ownership for the idea long before Osborne. Those of you from the era may have discovered the genre simultaneously. It was common practice to create our own mixtapes by borrowing records or recording songs from the radio. When you tired of them, you tape over what you had, each iteration leaving snippets of sounds from previous recordings. The tapes included samples, half-songs, soundbites and audio ephemera that I’d call accidental rather than found music.But is it music or just nonsense that will go away? As mentioned, Osborne’s work is exhausting, and yet there is an artistic factor in the time invested in creating the found work. Not so much with James Kirby’s work. Of his early work, Kirby called it a “horrific family fortieth birthday party where all of a sudden fights erupt…” His most recent work, a piece some six hours long, “Everywhere at the End of Time,” is something altogether more perplexing, and lazy. Don’t get me wrong, I kind of enjoy its ambient, elevator, ballroom at the Overlook Hotel dreaminess (The Shining), but is it music? What Kirby has done is to merely take American standards lifted from 78rpm records and added a haunted mansion-esque distortion to it. The piece is supposedly a soundtrack to dementia, and while I can see that, is this just piracy of those long gone unable to fight for their intellectual property? I love it and hate it, and like the work of Duchamp, if it weren’t “art,” I’d probably pee on/in it.

Here, I have to take ownership for the idea long before Osborne. Those of you from the era may have discovered the genre simultaneously. It was common practice to create our own mixtapes by borrowing records or recording songs from the radio. When you tired of them, you tape over what you had, each iteration leaving snippets of sounds from previous recordings. The tapes included samples, half-songs, soundbites and audio ephemera that I’d call accidental rather than found music.But is it music or just nonsense that will go away? As mentioned, Osborne’s work is exhausting, and yet there is an artistic factor in the time invested in creating the found work. Not so much with James Kirby’s work. Of his early work, Kirby called it a “horrific family fortieth birthday party where all of a sudden fights erupt…” His most recent work, a piece some six hours long, “Everywhere at the End of Time,” is something altogether more perplexing, and lazy. Don’t get me wrong, I kind of enjoy its ambient, elevator, ballroom at the Overlook Hotel dreaminess (The Shining), but is it music? What Kirby has done is to merely take American standards lifted from 78rpm records and added a haunted mansion-esque distortion to it. The piece is supposedly a soundtrack to dementia, and while I can see that, is this just piracy of those long gone unable to fight for their intellectual property? I love it and hate it, and like the work of Duchamp, if it weren’t “art,” I’d probably pee on/in it.

Published on July 26, 2020 14:00

July 24, 2020

Calif. - Buy This Book!

Get your copy of Calif. by R.J. Stowell at Amazon or read it on your Kindle. And remember, Kindle Unlimited is free the first month. Thousands of titles from Harry Potter to Lord of the Rings - and Calif., of course! Here's the link.

Watch with sound, share and enjoy!

Signed copy? Contact me at rjsomeone@gmail.com - $12.00 - includes shipping.

Published on July 24, 2020 08:59

July 23, 2020

This is Difficult - Postal Service and Dntel

It's difficult at times to decipher the differences between AM10s and personal faves, even for me and I wrote the rubric. I started this article by looking back at Dntel's Life is Full of Possibilites, having given it pretty high honors when it came out. Here was the perfect mix of computer geeks and hipsters - all my favorites creating the ultimate sonic landscape - but is it a record or an Epcot soundtrack with the occasional vocal? Indeed, this isn't an album for many, and despite its musicianship and production and influence, it's not a ten or a nine - probably a six. It is indeed Jimmy Tamborello's finest moment (it is undeniably his moment), and I've listened to it a hundred times, but it's nowhere near a 10, rescue vehicle cover art notwithstanding.

It's difficult at times to decipher the differences between AM10s and personal faves, even for me and I wrote the rubric. I started this article by looking back at Dntel's Life is Full of Possibilites, having given it pretty high honors when it came out. Here was the perfect mix of computer geeks and hipsters - all my favorites creating the ultimate sonic landscape - but is it a record or an Epcot soundtrack with the occasional vocal? Indeed, this isn't an album for many, and despite its musicianship and production and influence, it's not a ten or a nine - probably a six. It is indeed Jimmy Tamborello's finest moment (it is undeniably his moment), and I've listened to it a hundred times, but it's nowhere near a 10, rescue vehicle cover art notwithstanding. So, I crossed out Dntel and replaced it with the Postal Service. Give Up on the other hand is a real album with real hits and Gibbard and Tamborello and Jenny Lewis of Rilo Kiley . There's no fluff. Every track is spot on. Gibbard has released seven LPs with his day-job, Death Cab, but many of his best tunes are here on Give Up. It is indeed the electronic album that I'd hoped for since John Cage in the psychedelic 60s. It speaks in ways that Depeche Mode and Erasure failed to do in the 80s, but is that just me? Is it a ten?

So, I crossed out Dntel and replaced it with the Postal Service. Give Up on the other hand is a real album with real hits and Gibbard and Tamborello and Jenny Lewis of Rilo Kiley . There's no fluff. Every track is spot on. Gibbard has released seven LPs with his day-job, Death Cab, but many of his best tunes are here on Give Up. It is indeed the electronic album that I'd hoped for since John Cage in the psychedelic 60s. It speaks in ways that Depeche Mode and Erasure failed to do in the 80s, but is that just me? Is it a ten? How about mostly? Does that count?

No, see, that's where it all comes tumbling down. I started this thing to be objective. I have my faves and they're my 10s, but they're not AM10s. Life is Full of Possibilities is a solid AM7. Eleven years on and Give Up has a shot at longevity and an AM8. These are two of my favorite albums and by a lot of my favorite people, but it's not about me. This is Absolute Magnitude.

Published on July 23, 2020 10:07

July 22, 2020

am@random - Death Cab For Cutie

One of my favorite bands, Death Cab For Cutie reached "such great heights" with 2008's Narrow Stairs, particularly with the song most associated with the band, "I Will Possess Your Heart." While I was a Death Cab fan back as far as the 90s, it wasn't until Ben Gibbard's side project, Postal Service, came along that I rediscovered the band. "Such Great Heights" and "The District Sleeps Alone Tonight," were among those great tracks that took me out of my 90s doldrums. On top of that, Death Cab released Transatlantacism. Times were good.

Three years later, Narrow Stairs would be one of the 00s best LPs, featuring "Bixby Canyon Bridge," the video here, and "Cath." BTW: In 1967, the Bonzo Dog Band wrote "Death Cab For Cutie" for their album Gorilla and performed an Elvis-like tribute in The Beatles' Magical Mystery Tour film. So, no, it was not pulling random words from a fishbowl; Ben Gibbard simply liked the obscurity of the name and the Beatles reference.

Ben Gibbard said of the album's opening track, "Bixby Canyon Bridge," "There’s a real dramatic landscape change two minutes into the song… [it] becomes this big, riffy, guitar rock song… I think it sets a tone for the album that this record is going to be a very different experience." Opening with a warm, faraway tenor and Jack Kerouac inspired lyrics, the pounding rhythm is reinforced with bass and distorted guitar, an effect not dissimilar to the break of Radiohead’s "Creep" (which may come as a bit of a shock for those expecting the same ol' Death Cab). "I Will Possess Your Heart" is equally reminiscent of Radiohead's experimentalism with its hypnotic bass line, see-sawing major and minor tonalities, its echoing piano and looping guitar.

Much has been made of Death Cab For Cutie's sixth studio album as a darker, tougher and more experimental record and after the dizzying popularity of their exposure through TV (The O.C.), on radio ("I Will Follow You Into The Dark") and on the internet, what was previously a beloved indie concern was now getting the widespread fanbase, and recognition, they deserved. The problem with the mainstream is it tends to dilute what was great about an act pre-fame. Narrow Stairs is a reaction against this, an attempt to avoid any of the distillation and "selling-out" criticisms. While Gibbard's lyrics are less elliptical and more direct than previous albums, the music is captivated by the spirit of experimentalism of their pre-Plans releases when they didn’t need to worry about struggling for validation or meeting expectations.

Published on July 22, 2020 05:50

July 21, 2020

It's more or less the other way...

By 1999 we had Napster and dial-up (“We’re gonna party like it’s…”). Any song we wanted took just five to eleven minutes to download – what a world! Then they started calling it piracy. Back in the 70s we’d save our allowance, buy an LP and a six-pack of cassettes - I bought Relayer, Beck got Houses of the Holy, and Buick got Ziggy Stardust; it was

By 1999 we had Napster and dial-up (“We’re gonna party like it’s…”). Any song we wanted took just five to eleven minutes to download – what a world! Then they started calling it piracy. Back in the 70s we’d save our allowance, buy an LP and a six-pack of cassettes - I bought Relayer, Beck got Houses of the Holy, and Buick got Ziggy Stardust; it was For me, I miss the tactile sense of things. I want to hold it before I hear it, to open it and find the secret message on the inner band; and with the resurgence of vinyl, it seems I’m not alone. Still there are those who covet the digital ideology, who want everything, and for free. There’s a pervasive sense of entitlement or validation: “I bought Sgt. Pepper on vinyl, then in stereo; I had the cassette and got the CD through a record club – I’m not paying for it on iTunes!”

Yet funny things happen on Miro and Pirate Bay. On July 9, 2014, what was purportedly Pink Floyd’s The Endless River was leaked through many a torrent. While the specifics of the album were under wraps, it was general knowledge that the Floyd offering would contain re-workings of songs that Gilmour and Mason completed with Rick Wright during The Division Bell sessions. Instead what was leaked was inconsequential noise, a few minutes of flatulence and what was obviously not Pink Floyd.

Yet funny things happen on Miro and Pirate Bay. On July 9, 2014, what was purportedly Pink Floyd’s The Endless River was leaked through many a torrent. While the specifics of the album were under wraps, it was general knowledge that the Floyd offering would contain re-workings of songs that Gilmour and Mason completed with Rick Wright during The Division Bell sessions. Instead what was leaked was inconsequential noise, a few minutes of flatulence and what was obviously not Pink Floyd.Less obviously, and utilizing the German band Velveteen as its ruse (with “I Will Possess Your Heart” the only legitimate DCfC track), Narrow Stairs was leaked on April Fool’s Day 2008. Everyone bought into it; Velveteen so seamlessly fitting into the Death Cab mold. Quickly, though, the reality became apparent as several terrorist cells or notorious torrent managers claimed responsibility. Still the ruse persevered. Even upon the official release of Narrow Stairs on May 8th, many were still listening to their cherished pirated copies, having pulled something over once again on the RIAA. Beware all ye who enter here: the last song on the pirated album remains the incorrect track on many of today's torrents. What should be “The Ice is Getting Thinner” is actually Velveteen’s equally eloquent “The Big Layoff,” though the song title on the torrent remains the former. That’s right, you may very well be listening to the wrong, albeit climactic, final song.

"The Big Layoff" is plenty Death Cabby, and of itself a tribute to a band that Velveteen admit as a major influence. One of the indicators is vocalist Carsten Scheauff, whose hushed voice is a dead ringer for Ben Gibbard’s, circa The Photo Album. His lyrics employ the occasional picaresque reality as well. In the lo-fi opening track to Velveteen's Home Waters ("Prologue: Plastic Cups"), Scheauff softly re-counts: "I held your hair while you threw up/ and dragged you down the stairs./ And outside we cracked plastic cups/ and I drank from your can." It’s simplistic and familiar, something we can all picture in our minds, something straight out of the Death Cab playbook; nonetheless, it’s “The Big Layoff” that still masquerades on Narrow Stairs. So go, right now, listen again. If the lyrics to your version of "The Ice is Getting Thinner" are those you find below, you’ve been duped, my pirate friend. Aargh.

"The Big Layoff" is plenty Death Cabby, and of itself a tribute to a band that Velveteen admit as a major influence. One of the indicators is vocalist Carsten Scheauff, whose hushed voice is a dead ringer for Ben Gibbard’s, circa The Photo Album. His lyrics employ the occasional picaresque reality as well. In the lo-fi opening track to Velveteen's Home Waters ("Prologue: Plastic Cups"), Scheauff softly re-counts: "I held your hair while you threw up/ and dragged you down the stairs./ And outside we cracked plastic cups/ and I drank from your can." It’s simplistic and familiar, something we can all picture in our minds, something straight out of the Death Cab playbook; nonetheless, it’s “The Big Layoff” that still masquerades on Narrow Stairs. So go, right now, listen again. If the lyrics to your version of "The Ice is Getting Thinner" are those you find below, you’ve been duped, my pirate friend. Aargh.All the summer's passed Memberships apply So here comes your time Happiness required

It's more or less the other way

It's more or less the other way

Published on July 21, 2020 09:05

July 19, 2020

Hanging On The Telephone

Let’s go all the way back to 1958. The Big Bopper’s “Chantilly Lace” opens with this intro: “Hello, Baby. Yeah, this is the Big Bopper speakin'. Oh, you sweet thing. Do I what? Will I what? Oh baby, you know what I like.” 60 years ago, and yet it’s not the first song about a telephone. Head back another 20 years for Glenn Miller’s “Pennsylvania 6-5000.” Whatever the history, telephones and unrequited love go hand in hand. The music video is Blondie from Parallel Lines, a cover of the 1976 release by The Nerves, but Debbie Harry and Co. weren’t done with the phone; in 1980, an odd mix of punk and disco hit its peak with the Giorgio Moroder produced theme to the film American Gigolo, "Call Me."

My favorite of the telephone songs is my wife’s least favorite in the world: Jim Croce’s “Operator.” (“Seriously, he can’t make his own phonecall? Is he really hitting on her?”) From the 70s as well, there’s Yes’s “Long Distance Runaround” and ELO’s “Telephone Line.” “Okay, so no one’s answering.” Yep, unrequited love and technology. There’s “Cats in the Cradle,” from Harry Chapin and Todd Rundgren’s “Hello It’s Me.” Telephones spell trouble. Another of my favorites comes from 10CC, “Don’t Hang Up,” an epic mini-opera about how the phone plays its role in crushing our designs on love.Funny, we don’t memorize phone numbers anymore, but there isn’t anyone who doesn’t know Jenny’s, 867-5309. On the flip side of that, Michael Stipe uses that little trick from the 90s to get ahold of his special someone: "Star 69." (If it wasn’t for Star 69, btw, I may never have dated and married my wife – I forgot to leave my number on her answering machine.)Here’s one I don’t understand. It’s 2012 and Adam Levine of Maroon 5 is calling from a “Payphone.” Did they even have payphones in 2012?

Published on July 19, 2020 05:13

July 16, 2020

Storytelling and Ideas - Progressive Rock and Poetry

"I bought eggs," is not a story.

"I bought eggs," is not a story.Even if a few characters are tossed into the mix and the reader learns that you and James went to a farm stand to get fresh eggs on the way to Chloe's house and you bought them from the millennial chick with purple hair and a sleeve tattoo who left her job at a nonprofit in DC to come back home and restart the family farm — it still isn’t a story, it's a report. It isn't a story because there is nothing at stake for either the teller or the listener, the buyer or the seller.

Such is not the case with poetry. From ee cummings to Childish Gambino, poetry, while it often indeed tells a story, is about ideas. Thick as a Brick, the anti-concept LP, when all is considered – theme, poetry, ideas, Gerald Bostock, the ruse, the newspaper – is complex storytelling along the lines of a mystery novel in which all the pieces must be put together. But separate the poetry from its incidental parts and the poem itself, despite its epic length (long enough to be in italics rather than quotes), is more a collection of ideas.

Really don’t mind if you sit this one out.

Really don’t mind if you sit this one out.My word’s but a whisper — your deafness a SHOUT.

The poem opens with a slight aimed at the concert audience who can't sit through a performance of quiet songs, at least according to Ian Anderson, but more, the insult is meant for a wider audience – for society's leaders and elders, who won't listen anyway.

I may make you feel but I can't make you think.

Your sperm’s in the gutter — your love’s in the sink.

Society is driven by lust. The only way "I" can make an impression is to appeal to base senses. Morals are in the gutter and common sense has gone down the drain. (My how this feel's like Trump's America).

So you ride yourselves over the fields

and you make all your animal deals

Society moves through life without stopping to think, like animals.

And your wise men don't know how it feels

to be thick as a brick.

The "wise men" know nothing, consider the source; the implication that we should all think for ourselves.

And the sand-castle virtues are all swept away

in the tidal destruction

the moral melee.

The elastic retreat rings the close of the play

as the last wave uncovers

the newfangled way.

Beautiful metaphor. Anderson describes society's fickle virtues and morals by likening them to sand-castles that crumble with a new set of waves.

But your new shoes are worn at the heels

and your suntan does rapidly peel

Whatever is shiny and new (i.e. a new moral/religious fad) quickly becomes dull and worn, just like a suntan which looks good on you, but only for a while.

And your wise men don’t know how it feels

to be thick as a brick.

The idea: think for yourself. The poem on its own is clever but not genius. The genius is realized when the parts are assembled and brought to life through the musicianship. That's what music is all about.

The idea: think for yourself. The poem on its own is clever but not genius. The genius is realized when the parts are assembled and brought to life through the musicianship. That's what music is all about.Often, though, ideas are more random. When Cummings writes "Nobody, not even the rain, has such small hands," ideas are reduced to images. And that's what we find in progressive rock more often than not. From "Close to the Edge" to Gentle Giant's take on R.D. Laing's "Knots," progressive rock lyrics are all about imagery. Indeed, so is progressive rock's symphonic tone. Like Beethoven's 6th invokes a sense of the pastoral, Camel's The Snow Goose tells a story that, while know to Scandinavians, is left to an American audience to decipher. Any sophisticated listener (and if you read about music, that's who you are) will find the story in this lengthy instrumental piece.

Seriously, "Sharp. Distance./ How can the wind with its arms all around me?" means nothing (how can the wind what?), but one is a buffoon if the imagery coupled with the music doesn't conjure up Roger Dean-like imagery.

Published on July 16, 2020 07:50

July 15, 2020

The Origins of Prog

"But I don't like country." "You like the Eagles?" "Yeah." "Then you like country." It's simple to alienate people by categorizing their music in a bent with which they can't associate. Not recognizing the country and folk-rock (albeit psychedelic) aspects of bands like The Byrds, The Flying Burrito Brothers and CSN is absurd. That same kind of animosity abounds between those who do and don't appreciate progressive rock.

The mention of the term will result in blank stares that generally lead to the question, "What is progressive music?" We can generalize: Longer songs (or epics); time changes and odd time signatures; complex, sophisticated instrumentation and composition; conceptual ideas and heightened, lyrical content; classical and jazz influences. These general guidelines hold true now, as they did during prog's heyday in the mid-70s. Tracing prog's history is a bit more speculative. What may be confusing is mistaking what is avant-garde for progressive. While prog can be extremely experimental (think "We Have Heaven" from Yes or Gentle Giant's "Knots"), the utterly experimental and avant-garde Trout Mask Replica cannot be mistaken as progressive.

The mention of the term will result in blank stares that generally lead to the question, "What is progressive music?" We can generalize: Longer songs (or epics); time changes and odd time signatures; complex, sophisticated instrumentation and composition; conceptual ideas and heightened, lyrical content; classical and jazz influences. These general guidelines hold true now, as they did during prog's heyday in the mid-70s. Tracing prog's history is a bit more speculative. What may be confusing is mistaking what is avant-garde for progressive. While prog can be extremely experimental (think "We Have Heaven" from Yes or Gentle Giant's "Knots"), the utterly experimental and avant-garde Trout Mask Replica cannot be mistaken as progressive.

Picking a starting point is a bit like putting a pin in a globe to choose one's vacation. This writer sticks a pin in The Mothers of Invention's Freak Out from 1966, in particular, "Help, I'm a Rock." Zappa's sophomore release, Absolutely Free, may more specifically be progressive, but I'll stick with Freak Out as where it all began.

What appears today as run of the mill (hardly) was ground-breaking in 1967. The idea of fusing psychedelic rock with orchestral arrangements was an improbable marriage. The Moody Blues somehow made it work on the prog classic Days of Future Passed. A true concept album, Days of Future Passed is thematic in that it follows a day's activity. As "The Day Begins" Graeme Edge commands the sun to rise. The optimism of the early morning is reflected in Michael Pinder's "Dawn is a Feeling" and in Ray Thomas' "Another Morning". By the afternoon, the recording takes on a surreal quality typical of later psychedelic recordings; indeed, John Lodge's compositions ("Peak Hour", "Forever Afternoon") are truly inspired. Despite the "typical day," the symphonic arrangements with the London Festival Orchestra are far from ordinary. In essence, Days was a fluke, a mistake, but for scores of flower children, the LP was their first exposure to classical orchestration and soaring melodies. In actuality, the album is more proto-prog than prog: for all of its orchestral ambitions, the songs stick largely to pop song formats. And yet, the way the group tried to seriously meld themselves with the orchestra, rather than simply use it as a sweetening device as in earlier pop music, was important--it's the *intent* here that counts. Not to mention, the group's unabashedly "cosmic" aspirations which would be a more defining characteristic of prog than Zappa's more biting, punkish social satire.

What appears today as run of the mill (hardly) was ground-breaking in 1967. The idea of fusing psychedelic rock with orchestral arrangements was an improbable marriage. The Moody Blues somehow made it work on the prog classic Days of Future Passed. A true concept album, Days of Future Passed is thematic in that it follows a day's activity. As "The Day Begins" Graeme Edge commands the sun to rise. The optimism of the early morning is reflected in Michael Pinder's "Dawn is a Feeling" and in Ray Thomas' "Another Morning". By the afternoon, the recording takes on a surreal quality typical of later psychedelic recordings; indeed, John Lodge's compositions ("Peak Hour", "Forever Afternoon") are truly inspired. Despite the "typical day," the symphonic arrangements with the London Festival Orchestra are far from ordinary. In essence, Days was a fluke, a mistake, but for scores of flower children, the LP was their first exposure to classical orchestration and soaring melodies. In actuality, the album is more proto-prog than prog: for all of its orchestral ambitions, the songs stick largely to pop song formats. And yet, the way the group tried to seriously meld themselves with the orchestra, rather than simply use it as a sweetening device as in earlier pop music, was important--it's the *intent* here that counts. Not to mention, the group's unabashedly "cosmic" aspirations which would be a more defining characteristic of prog than Zappa's more biting, punkish social satire.

While The Moodies were busy attempting to meld rock and orchestral sounds, Keith Emerson, and The Move were busy incorporating classical and jazz elements within a tighter four-piece (later three-piece) rock band arrangement, using only his considerable virtuosity at the keyboard and a partnership with Robert Moog. The results would do more to influence prog-rock, and keyboards in general, than any other album for years to come. While "Emerlist Davjack" is more of a transitional album between psychedelia and prog, the LP is as progressive as much of ELP's later work.

Also in 1967, the Moodies were back with In Search of the Lost Chord. Here we may find the very first intrinsically progressive LP. A mini-suite opens with "House Of Four Doors," a solemn and somewhat mystical number that features the sound of different doors opening into different musical worlds: medieval guitar and flute, a baroque harpsichord, and a 19th-century orchestra, leading to the fourth and final door which opens cleverly into the next song, "Legend Of A Mind." This psychedelic classic is a tribute to acid guru Tim Leary, which features a trippy mellotron hook played with a pitch bend. This upbeat track features a catchy melody and a series of exciting time changes, constantly building in strength until the piece quiets down for a mystical flute solo and more of the pitch-bended mellotron for maximum psych thrills. The break continues this mellotron/flute duet for a while, stretching the song way past pop boundaries and into solid prog territory, the track's orchestral grandeur becoming apparent as the band rejoins and gradually plays in a faster and faster tempo, soaring high until the chorus triumphantly returns. "House Of Four Doors" returns for a brief reprise, sounding moody and contemplative, a tambourine being stricken ritually as the group sings of different paths on the quest to enlightenment. And that's just side one.

Also in 1967, the Moodies were back with In Search of the Lost Chord. Here we may find the very first intrinsically progressive LP. A mini-suite opens with "House Of Four Doors," a solemn and somewhat mystical number that features the sound of different doors opening into different musical worlds: medieval guitar and flute, a baroque harpsichord, and a 19th-century orchestra, leading to the fourth and final door which opens cleverly into the next song, "Legend Of A Mind." This psychedelic classic is a tribute to acid guru Tim Leary, which features a trippy mellotron hook played with a pitch bend. This upbeat track features a catchy melody and a series of exciting time changes, constantly building in strength until the piece quiets down for a mystical flute solo and more of the pitch-bended mellotron for maximum psych thrills. The break continues this mellotron/flute duet for a while, stretching the song way past pop boundaries and into solid prog territory, the track's orchestral grandeur becoming apparent as the band rejoins and gradually plays in a faster and faster tempo, soaring high until the chorus triumphantly returns. "House Of Four Doors" returns for a brief reprise, sounding moody and contemplative, a tambourine being stricken ritually as the group sings of different paths on the quest to enlightenment. And that's just side one.

By 1968 the genre would fully emerge with bands like Tomorrow, Mabel Greer's Toyshop, Yes and King Crimson, not to mention the Canerbury Scene which was progressive all the way back to 1964. Progressive Rock would explode into the mainstream in the mid-70s with Tull, ELP and Genesis, finally self-engrandizing itself so fully that it fell by the wayside amidst the clash of punk and disco, then reemerge in the 90s with bands like Porcupine Tree. Interesting that Steven Wilson would look back so fondly on LPs like Gentle Giant's The Power and the Glory, remaster and mix them and offer them up to a new generation.

The mention of the term will result in blank stares that generally lead to the question, "What is progressive music?" We can generalize: Longer songs (or epics); time changes and odd time signatures; complex, sophisticated instrumentation and composition; conceptual ideas and heightened, lyrical content; classical and jazz influences. These general guidelines hold true now, as they did during prog's heyday in the mid-70s. Tracing prog's history is a bit more speculative. What may be confusing is mistaking what is avant-garde for progressive. While prog can be extremely experimental (think "We Have Heaven" from Yes or Gentle Giant's "Knots"), the utterly experimental and avant-garde Trout Mask Replica cannot be mistaken as progressive.

The mention of the term will result in blank stares that generally lead to the question, "What is progressive music?" We can generalize: Longer songs (or epics); time changes and odd time signatures; complex, sophisticated instrumentation and composition; conceptual ideas and heightened, lyrical content; classical and jazz influences. These general guidelines hold true now, as they did during prog's heyday in the mid-70s. Tracing prog's history is a bit more speculative. What may be confusing is mistaking what is avant-garde for progressive. While prog can be extremely experimental (think "We Have Heaven" from Yes or Gentle Giant's "Knots"), the utterly experimental and avant-garde Trout Mask Replica cannot be mistaken as progressive.Picking a starting point is a bit like putting a pin in a globe to choose one's vacation. This writer sticks a pin in The Mothers of Invention's Freak Out from 1966, in particular, "Help, I'm a Rock." Zappa's sophomore release, Absolutely Free, may more specifically be progressive, but I'll stick with Freak Out as where it all began.

What appears today as run of the mill (hardly) was ground-breaking in 1967. The idea of fusing psychedelic rock with orchestral arrangements was an improbable marriage. The Moody Blues somehow made it work on the prog classic Days of Future Passed. A true concept album, Days of Future Passed is thematic in that it follows a day's activity. As "The Day Begins" Graeme Edge commands the sun to rise. The optimism of the early morning is reflected in Michael Pinder's "Dawn is a Feeling" and in Ray Thomas' "Another Morning". By the afternoon, the recording takes on a surreal quality typical of later psychedelic recordings; indeed, John Lodge's compositions ("Peak Hour", "Forever Afternoon") are truly inspired. Despite the "typical day," the symphonic arrangements with the London Festival Orchestra are far from ordinary. In essence, Days was a fluke, a mistake, but for scores of flower children, the LP was their first exposure to classical orchestration and soaring melodies. In actuality, the album is more proto-prog than prog: for all of its orchestral ambitions, the songs stick largely to pop song formats. And yet, the way the group tried to seriously meld themselves with the orchestra, rather than simply use it as a sweetening device as in earlier pop music, was important--it's the *intent* here that counts. Not to mention, the group's unabashedly "cosmic" aspirations which would be a more defining characteristic of prog than Zappa's more biting, punkish social satire.

What appears today as run of the mill (hardly) was ground-breaking in 1967. The idea of fusing psychedelic rock with orchestral arrangements was an improbable marriage. The Moody Blues somehow made it work on the prog classic Days of Future Passed. A true concept album, Days of Future Passed is thematic in that it follows a day's activity. As "The Day Begins" Graeme Edge commands the sun to rise. The optimism of the early morning is reflected in Michael Pinder's "Dawn is a Feeling" and in Ray Thomas' "Another Morning". By the afternoon, the recording takes on a surreal quality typical of later psychedelic recordings; indeed, John Lodge's compositions ("Peak Hour", "Forever Afternoon") are truly inspired. Despite the "typical day," the symphonic arrangements with the London Festival Orchestra are far from ordinary. In essence, Days was a fluke, a mistake, but for scores of flower children, the LP was their first exposure to classical orchestration and soaring melodies. In actuality, the album is more proto-prog than prog: for all of its orchestral ambitions, the songs stick largely to pop song formats. And yet, the way the group tried to seriously meld themselves with the orchestra, rather than simply use it as a sweetening device as in earlier pop music, was important--it's the *intent* here that counts. Not to mention, the group's unabashedly "cosmic" aspirations which would be a more defining characteristic of prog than Zappa's more biting, punkish social satire. While The Moodies were busy attempting to meld rock and orchestral sounds, Keith Emerson, and The Move were busy incorporating classical and jazz elements within a tighter four-piece (later three-piece) rock band arrangement, using only his considerable virtuosity at the keyboard and a partnership with Robert Moog. The results would do more to influence prog-rock, and keyboards in general, than any other album for years to come. While "Emerlist Davjack" is more of a transitional album between psychedelia and prog, the LP is as progressive as much of ELP's later work.

Also in 1967, the Moodies were back with In Search of the Lost Chord. Here we may find the very first intrinsically progressive LP. A mini-suite opens with "House Of Four Doors," a solemn and somewhat mystical number that features the sound of different doors opening into different musical worlds: medieval guitar and flute, a baroque harpsichord, and a 19th-century orchestra, leading to the fourth and final door which opens cleverly into the next song, "Legend Of A Mind." This psychedelic classic is a tribute to acid guru Tim Leary, which features a trippy mellotron hook played with a pitch bend. This upbeat track features a catchy melody and a series of exciting time changes, constantly building in strength until the piece quiets down for a mystical flute solo and more of the pitch-bended mellotron for maximum psych thrills. The break continues this mellotron/flute duet for a while, stretching the song way past pop boundaries and into solid prog territory, the track's orchestral grandeur becoming apparent as the band rejoins and gradually plays in a faster and faster tempo, soaring high until the chorus triumphantly returns. "House Of Four Doors" returns for a brief reprise, sounding moody and contemplative, a tambourine being stricken ritually as the group sings of different paths on the quest to enlightenment. And that's just side one.

Also in 1967, the Moodies were back with In Search of the Lost Chord. Here we may find the very first intrinsically progressive LP. A mini-suite opens with "House Of Four Doors," a solemn and somewhat mystical number that features the sound of different doors opening into different musical worlds: medieval guitar and flute, a baroque harpsichord, and a 19th-century orchestra, leading to the fourth and final door which opens cleverly into the next song, "Legend Of A Mind." This psychedelic classic is a tribute to acid guru Tim Leary, which features a trippy mellotron hook played with a pitch bend. This upbeat track features a catchy melody and a series of exciting time changes, constantly building in strength until the piece quiets down for a mystical flute solo and more of the pitch-bended mellotron for maximum psych thrills. The break continues this mellotron/flute duet for a while, stretching the song way past pop boundaries and into solid prog territory, the track's orchestral grandeur becoming apparent as the band rejoins and gradually plays in a faster and faster tempo, soaring high until the chorus triumphantly returns. "House Of Four Doors" returns for a brief reprise, sounding moody and contemplative, a tambourine being stricken ritually as the group sings of different paths on the quest to enlightenment. And that's just side one.By 1968 the genre would fully emerge with bands like Tomorrow, Mabel Greer's Toyshop, Yes and King Crimson, not to mention the Canerbury Scene which was progressive all the way back to 1964. Progressive Rock would explode into the mainstream in the mid-70s with Tull, ELP and Genesis, finally self-engrandizing itself so fully that it fell by the wayside amidst the clash of punk and disco, then reemerge in the 90s with bands like Porcupine Tree. Interesting that Steven Wilson would look back so fondly on LPs like Gentle Giant's The Power and the Glory, remaster and mix them and offer them up to a new generation.

Published on July 15, 2020 07:52