Chuck Wendig's Blog, page 100

January 18, 2017

PSA: Fake Donald Trump Is Maybe Not Your Best Marketing Plan

Yesterday, an author — a bestselling author — went around and did a series of tweets with fake Donald Trump tweets, and these fake tweets were Donald Trump mocking this author’s book. One of those tweets has since gone around the ol’ retweet carousel around 12,000 times. In part because it was retweeted by a number of celebrities, most of whom seemed to believe that it was real. If you look at the tweet and its responses, this is a common theme — a lot of people thought it was real. Which isn’t surprising, because that’s the angle, isn’t it? Trump on any day of the week might be using his global platform as president-elect to (sigh) rant and rail at everything from automakers to world leaders to Saturday Night Live. Listen, let’s be real: if Trump one morning decided to tweet rant about like, penguins, it would not shock any of us. (“Penguins. Totally biased!! Tiny flipers and cant fly. SAD”). It wouldn’t shock us because his Twitter feed is a lunatic’s parade of rage and hurt butts, a constant pouty stream of fragile ego shrieking and wailing from between the bars of its wrought iron cage.

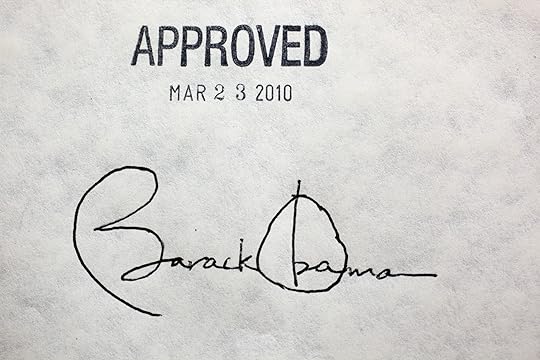

So, to see Obama one day talk about how important books are to him, and what writing has meant for him (seriously, he promoted The Three-Body Problem, holy shit awesome), and then the next day to see Trump railing on some random author’s book — it’s legit believable.

It’s just not true. That’s the first part of the PSA. I’m seeing it go around, so please know:

That Trump tweet is fake.

The author likely didn’t mean any harm here (though since being called on it, it would’ve been nice to see the tweets deleted or at least a public addendum suggesting that they were, indeed, fake). I assume he meant it as something halfway between a joke and a marketing ploy. And I’m sympathetic, because hey, getting word out about your book — even as a bestselling author — is a grim, strange magic. Having something go viral around your book has value, at least in getting attention — ideally, it also gets sales. Hell, I’m helping him with the job just by talking about it. I didn’t know about his book before yesterday, and now I do.

Since that time, though, not only has the tweet gone around the world a couple times, I’ve now seen other writers trying the same thing — mostly on Facebook, actually — again in the vague hopes of I guess doing a bit and also serving the Marketing Gods. And, just as with the original tweet, I’m seeing some people take the bait and think it’s real.

Here’s why this is probably not an ideal marketing strategy.

First, we live in an age of fake news, and sure, I get that maybe you’re trying to lean into that and use that as leverage for so-called “satire” (by the way, satire and marketing ploys don’t go together, and once something is a marketing ploy, it ceases to be satire). But this isn’t The Onion. This isn’t sharp, incisive comedy that is clearly fake. This looks like fake news, and people believed it as such, and even in a world where Comrade Dumpkov is who he is, it’s dangerous to put more kooky words into his mouth and to distract from the reality of the many actually awful things he says. Don’t headfuck us further. We have enough shit to worry about.

Second, there’s the creepy shine of exploitative opportunism here, because just days before, Trump attacked Civil Rights icon, John Lewis, and as a result, that icon’s sales jumped per book by a figure in the hundreds of thousands of percent. Trump is a guy who says, fuck bees, and tomorrow, everybody’s a beekeeper. Trump tells you to eat Trump Steaks and it’s like, okay, those are poison, don’t touch those, you’d be better off eating one of those Mr. Clean Magic Erasers. But the timing here is bad. You don’t really want to come across as an author who thinks, Hey, I can be just like John Lewis, and I’ll fake Trump trash-talking me, right? Even if that’s not what the author thought, it vibes that way. John Lewis is an American icon, and what he had to go through to get here, where he gets yelled at by a bloated ego-buffoon is not currency for you, for me, for any of us. Look at it a different way: would you somehow tweak and twist Black Lives Matter into a way to sell your book? Would you say BOOK LIVES MATTER to sell your book? Do you see where that starts to feel sorta gross, how it feels itchy and uncomfortable using real life and real suffering as rungs on a ladder?

Third, Trump is bad people. He’s advocated sexual assault, he’s advocated banning people based on their religion, he yells at Civil Rights icons and makes racist assumptions about their districts — I’m sure in his quieter hours, he kills and eats bald eagles while wiping his ass with the Constitution. So, looking at him, I have a hard time seeing opportunity. I have a hard time seeing him as a good marketing platform, especially because that platform would springboard from his horribleness. His awfulness isn’t a tool. If you could imagine yourself going back in time and using Actual Hitler as a way to sell your book or your widget or your whatever, then don’t do it with Actual Trump, either. We’re having a hard enough time with this guy, with fake news, with toxicity across social media to try to trade-off on that as some kind of marketing tactic. Again, that’s probably not what that author was doing here. Maybe it was, in all honesty, just a joke. Certainly I’ve made jokes about Comrade Dumpkov, and will continue to, because if we can’t laugh then we’ll chew through the rebar we have to bite on to repress the existential scream that continues to try to escape our faces. But this tweet has gotten bigger than just a joke, and maybe there are better ways. If you’re an author considering aping this tactic, nnnnyeah don’t? And if you’re the author who used the tactic in the first place, maybe now’s a good time to deal with those tweets?

For the rest of us, it is once again a good time to remember that there’s a lot of fakey-fakey stuff out there, and some of it doesn’t mean to be harmful, some of it definitely does, and it’s on us to stay vigilant and keep an eye on verifying what we read and what we spread around.

January 16, 2017

Macro Monday Is Light As A Feather

I have little reason to post that feather, I suppose, except to remind you still that Blackbirds remains $1.99 for your electronic reading doojiggers:

At B&N, Amazon, Apple, Kobo and Google Play.

And as a shiny special bonus, there’s a very nice review at Publishers Weekly for Thunderbird: “This gritty, full-throttle series is what urban fantasy is all about, with bitter humor rounding out lyrical writing. It’s easy to root for this mouthy, rude, insensitive, but innately good young woman, and her story hits the reader like a double shot of rotgut.” It also gets a shout-out at B&N’s 25 SFF books to read in 2017, so yay.

And that’s it for now.

Go forth and good luck.

Pre-order Thunderbird now: Indiebound | Amazon | B&N

Sarah Gailey: Get Rich Or Die Trying — On Repealing The ACA

Fellow awesome writer person Sarah Gailey had some stuff to say about the class eugenics that lurk unspoken in the repeal of the Affordable Care Act, and if you know Sarah, you know that what she writes is worth reading. Just check out her work at Tor.com, or her upcoming novella (omg hippos), River of Teeth.

Healthcare is essential to human life.

Without it, people die. Babies die. Mothers die. Kids with allergies die. Grandfathers with pancreatic cancer die. People with disabilities die. A steelworker who gets his hand crushed, a farmer who gets bitten by a snake, a teacher who has a heart attack. Without doctors and medicine and treatment, people who get sick or injured die.

This is the endgame of the ACA repeal: death for those who can’t afford insurance and who can’t privately pay for healthcare. Death for the poor, death for the unemployed, death for the newly self-employed entrepreneur, death for the laborer with three part-time jobs and no benefits. Death for the widow who relied on her late husband’s insurance; death for the orphan who was a dependent. Death for the infant whose mother couldn’t afford birth control or prenatal care. Wealth or death: those are the choices.

While this may sound harsh, it shouldn’t be surprising. The social Darwinism that drives so much of America’s rhetoric — the pull-yourself-up-by-the-bootstraps narrative that undergirds the American Dream — makes a snug fit with the consequences of the ACA repeal. This is the comfort of the wealthy: those who can’t afford healthcare can’t afford it because they’re lazy. They didn’t try hard enough, so when they die, they have only themselves to blame.

“If you can’t afford treatment, you don’t get treatment.” This is the basic concept that drives opposition to universal healthcare — and yet, even that blunt statement flinches away from the true conclusion of its execution. The true conclusion is this: “if you can’t afford treatment, you deserve to die.” Those who can’t afford antibiotics will die of fevers. Those who can’t afford dental care will die of rotten teeth. Those who can’t afford chemotherapy will die of cancer.

In this scenario, the poverty that American morality has always scorned becomes a capital offense; the pursuit of wealth, a necessary route to survival. Never mind that wealth is overwhelmingly concentrated in populations of privileged white people with family legacies that are rooted in the exploitation of those who benefit from the programs like the ACA — never mind that. [8 people hold as much wealth as 3.6 billion — cdw] The bottom line is this: those who are not wealthy enough to afford the cost of healthcare will be eliminated.

How could this be allowed to happen? How, in our nation, which we call the wealthiest, the greatest, the strongest nation on earth? How could we propose to allow millions of citizens to go without the medical care they need? How?

Well. Let’s talk about eugenics.

For those who are unfamiliar with the concept, eugenics is a horrific application of selective breeding. To understand selective breeding, imagine a gardener who wants all of his pea plants to have purple flowers on them. He would have to weed out the pea plants with white flowers on them, and plant only seeds from the plants with purple flowers.

In 1937, a guy named Frederick Osborn proposed that the principles of selective breeding should be applied to the social order: encourage people with desirable traits to reproduce, and sterilize “undesirables” to remove their genes from the pool. Osborn’s ideas were heavily tied into the rhetoric of social Darwinism, which suggests that the law of natural selection applies to modern society: only the strong deserve to survive.

Many will rightly associate this concept with fascism and particularly with Nazi Germany — but it cannot be forgotten that eugenics was popular throughout the Western world, and particularly in the United States, during the early 20th century. Our country participated in the “removal” of traits which the government deemed undesirable — traits which included mental illness, physical disability, nonwhite heritage, and any sexual identity other than heterosexual. In 1927, the United States Supreme Court passed Buck v. Bell, which effectively legalized compulsory sterilization. Individuals were sterilized against their will, incapacitated, or killed under the euphemism of ‘euthanasia’.

Today, this practice is widely considered to be unethical, dehumanizing, and morally repugnant. The repeal of the ACA brings it to the forefront of American society, hidden behind a thin veil of capitalist ideology.

Does this embody the national character Americans claim to have? We call ourselves “the greatest nation in the world,” and “the land of opportunity.” We pride ourselves on our immense national wealth. We claim to have a social, political, and economic system upon which all others should be modeled — and yet we are debating a proposition that would leave millions of Americans at risk of death due to a lack of coverage. And so it is that we must ask ourselves: does an American morality that leaves the uninsured to die embody the universal right to life that is promised in the second sentence of our Declaration of Independence?

No. Instead, it embodies the darkest facet of the American perspective on capitalism: that citizens are justified only by their earnings, and that without justification through labor and wealth, the life of a citizen is not the concern of the American government. This is the America that we so consistently look away from: the America whose constitution was written solely for the benefit of landed white men. The America that pioneered early eugenics; the America that, years before Hitler’s rise to power, began attempting to rid itself of “undesirables.”

Today, those citizens who are not wealthy are being declared undesirable by the ACA repeal.

And we know what happens to undesirables.

January 13, 2017

Flash Fiction Challenge: Something That Scares You

This week, I want you to write about something that scares you.

This can be something overt and obvious (CHAINSAW CLOWNS) to something deeper (“I am afraid of losing my mind to Alzheimer’s”) — but I want you to take aim at it and lay it bare on the page and construct a story around it as best as you can.

You have 1000 words.

Story due by 1/20, noon EST.

Post at your online space, give us a link below.

Write your fear.

January 12, 2017

Why We Need The Affordable Care Act (ACA)

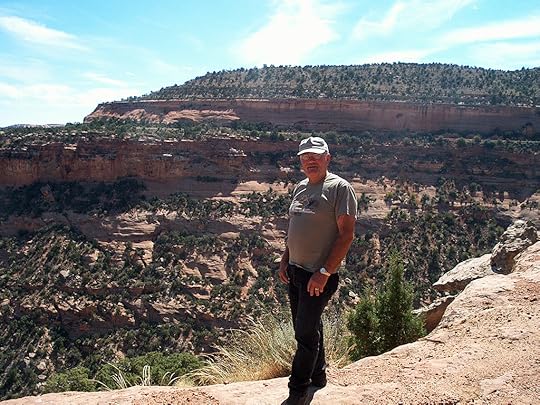

I posted this story about my father (seen below) on Twitter a little over a week ago.

It’s gone around quite a lot since then, and I’m happy it has. I don’t suspect the right cosystemyes have seen it, nor do I guess that if they did see it, they’d care, but the truth of the story remains the same: my father would be alive today if the ACA were in place then. And without the protections of the ACA that let me get healthcare for me and my family without the roadblock of pre-existing conditions, I could end up in my father’s shoes, too. I’m 40, now. Certainly not an old man, but not a young one. My father was only 63 when he passed. Last year I had pneumonia twice — and pneumonia is a killer. What if I were without health care? Would I have gone to the doc? Maybe. Maybe not as fast. Maybe I would’ve gone and had a stack of bills to pay for years to come, or maybe I would’ve waited too long and suffered more — or worse, got dead.

The ACA isn’t just about insurance. It’s a panoply of protections: line items that seem small on the surface but are huge to those that need them, provisions to protect women’s health, provisions to help us get free tests to prevent big diseases, coverage for autism therapy, calorie/nutrition information at restaurants. The ACA is designed to protect individuals, and not a system. It’s just the first volley, an imperfect one, but one that makes health insurance — and by proxy, health care — affordable and within reach for millions of Americans, including us poor sods in the creative class who really would rather not do without it. The ACA helps the middle-class, the lower-class, it helps women, it helps the disabled, and all of those will be disproportionately affected by its repeal.

Its repeal is very much about protecting a system over protecting the individual.

It’s about protecting profits.

It’s about protecting the upper class only.

That’s what you need to understand about all of this — it’s about money.

It’s about taking it from you and giving it to someone else. It’s about tax cuts for the rich, it’s about lobbyists, it’s about bolstering a system and removing the protections for the individual. It’s the same way that the venomous and vigorous defense of the gun industry isn’t about your rights, it’s about protecting profits. It’s about protecting a system of gains that exploits you and your fear. (And in all of this you will find perhaps no greater irony than the fact it is a Constitutional Right to protect your guns, but you have no such right to health care.) For the record, I’m not even against guns or gun ownership. I am decidedly pro. But don’t mistake the fight as one that cares about you. It’s one that cares about lining the pockets of people who assuredly are not you. And the same goes with the fight for health care. It cares nothing for you. It pretends to. The GOP talk a very good game when it comes to you, the middle-class. (Or, even better, you, the white male middle class.) But they don’t give a shit about you, either. They stoke racism and sexism and other-ism to make you fear phantom enemies. They say, “It’s THEM. It’s THOSE PEOPLE who are hurting you. They’re welfare-grabbers, they’re terrorists, they’re needy women, they’re the weak disabled, they’re sexual deviants who deserve what they get,” and they wave their hands and gesticulate and point, and you look in that direction. And while you do, mad as hell, they give you a little hip-check and slip a hand into your pocket — and then they steal your wallet. And what they don’t tell you, what they never ever want you to figure out, is that you’re just as marginal to them as those other groups. They pretend you have solidarity with them, oh, ho ho ho, we’re all white, we’re all just working class people, we all love America.

Then they rob you blind and blame it on someone else.

If they cared about you, they’d protect you.

And they don’t care.

They care about their money. They care about the richie-riches.

Not having the ACA shackles you to a job — and it makes keeping that job more important, so it’s harder to leave, which gives that employer more leverage over you. Which again, favors the employer. It doesn’t favor you, the worker. It helps your boss, and your boss’ boss, and it helps the investors. Once again: it helps the wealthy. It helps ensure that the creative class can’t survive either, because we’re out here on the margins, on the frontier of wild space. It means we need jobs to survive, too. It means we suffer under an ecosystem that exploits us, rather than one that is meant to help us. We outnumber them by a massive, unconquerable margin, and yet we are conquered. Because we buy the lie. We take the story sold to us that we too can be rich someday, that the wealthy got there because of hard work, that they will extend their hand to us and help us up — despite the reality, the constantly proven reality, that they will slap your hand away from the golden ladder the moment you dare to fucking reach for it, you prole, you peon, you paltry serf. And we nod and we smile and we continue to vote to make them richer and us poorer, we vote to give them the best health care and to kiss our own health goodbye. We vote for ignorance over awareness, for a single path that someone else designed for us, for limitation over freedom. We always vote for them instead of us.

But the ACA is about us. Planned Parenthood is, too.

The ACA and PP is about giving us access to not just affordable health care, but knowledge about our own health. Without it, we’re gonna break. People are going to be hurt. The marginalized will suffer first, but the middle-class will suffer next — the working class is long in the tooth with horror stories of when family members fall ill. Just like the story of my father, a man who would still be around if he had access to health care when he got cancer.

Help keep the ACA. It isn’t perfect, but as I say below, just because your car needs new belts isn’t a reason to drive it off a fucking bridge. Call your representatives (need a script?). Go to a rally. Coverage matters. They don’t have a replacement. They’ve tried 60 times to repeal the ACA and over the course of several years they have continued to come up dry with any, any kind of replacement. They’re pushing us all out of a plane and promising to figure out how to build a parachute as we plummet. (And the truth is, they’re really only concerned for the golden parachutes they give themselves and CEOs.)

Don’t help them.

Help us. All of us. You, me, your neighbor.

We need the ACA. Demand they fix it, not destroy it.

Demand they help us, not destroy us.

And gods help us, in 2018: vote.

* * *

[View the story “The Reality Of The ACA Going Away” on Storify]

January 10, 2017

Here’s How To Finish Your Revision, You Filthy Animal

this is not a soup you monster

CONGRATULATIONS, YOU HAVE SHAT OUT A BOOK.

You clenched up your middle and wrinkled your brow — then, from one of your creative holes poured this narrative slurry of words and ideas, this malformed gremlin egg of unhatched potential. On every page, characters flop and flail, they say stuff, they do stuff, and it all hangs together with rubbery tendon and braids of discolored flesh. You wrote a book. Nice job. Yes, high-five and fist-bump and go get a cupcake.

*swats cupcake out of your hand*

I DIDN’T SAY EAT THE CUPCAKE

I SAID GO GET THE CUPCAKE

YOU DON’T DESERVE A CUPCAKE YOU MONSTER

GOD YOU NEVER LISTEN

What? Did you think you were done? You’re not done. The book isn’t done. You can’t just dump a bunch of shit in a pot and call it soup. It’s gotta cook. You gotta taste it. You have to add some spices, you need to skim the fat, you must adjust the flavor as you go. You’re not done. What you clumsily slapped together is just a first draft. Or worse, it’s just a pile of mush, a zero-point-two-five draft.

You’ve got to edit that thing.

You’ve got to get that fucker in shape.

You wanna edit your book?

Here’s how you edit that book. (Translation: here’s how I edit that book, you do what you like, everybody’s different, you’re a beautiful glittery snowflake and I’m a beautiful glittery snowflake. Also, I know I’ve done editing posts before, but I thought one that approached it with fresh eyes — how I edit now, versus my thoughts on it years ago — would give me some clarity, and maybe you, as well. But really me. Who cares about you?)

(Also, please enjoy this Kubler-Ross Model Of Grief Associated With Editing And Rewriting)

1. Yeah, No, It’s Gonna Be Hard. Editing is harder than writing. Writing is just this freewheeling thing you do — you just go PLONKY PLICKY PLONK with your fingers on the keyboards and words squirt out. You write in a straight direction without care. It’s like riding a horse in a video game, you just get on and start moving and there’s no consequences and it’s all just pixels right now. Sweet, sweet consequence-free pixels. Yippee-ki-yay, ki-yah! But editing is like riding a horse in real goddamn life. Now, it fucking matters. You do it right or you break your pelvis on a rock or get stuck to a cactus, ass-first. It’s ride or die time. I learned that from Vin Diesel and he’s never wrong.

2. Look At It, Then Stop Looking At It. The first thing I do is I look at it. I don’t even look that long. I read my notes, I look over any other notes that have come in from my agent or from an editor or from that magical beans-eating hobo I entrusted with my manuscript. And then I experience existential despair. Because I fucked up. I failed. But that’s okay, and I have to remember that it’s okay. Because the first draft is always the fail draft. And I know this, and I’m comfortable with this in theory, but not always in practice. I need time to hyperventilate a little. I need time to realize that the beautiful machine I thought I created is basically just a cardboard box of dongles and wires from 1997 like you’d find in the back of an old-ass Radio Shack. The first draft is a ‘fuck you’ draft. And who is the first draft saying fuck you to? Me. Me when I’m about to revise that salty, surly sonofabooger. Shit goddamnit shit.

3. Now, Touch It, Just A Little. Poke that wriggling goblin. Go on. It’s time. It’s time to poke it, to open up the manuscript, just prod the squishy mess to see –

4. You Know What? Stop Touching It. OH GOD GROSS, NO, NOPE, NYET, NUH-UH. You know what? It’s too soon. It’s just too damn soon. I thought it was time. It was not time. Nope. Going to keep this Band-Aid on a little longer. The wounds are still fresh! The injury, still festering. I am not ready for the chirurgeon’s saw. *breathes into a bag*

5. It’s About Fermentation. Here is a truth about editing that I did not realize for a long time. Too long, really. Writing takes a lot of time up front where you’re not actually writing. Writing requires a long, mental brine-bath. Ideas have to steep and marinate and percolate. Your book isn’t a hamburger. It’s kim-chi, motherfucker. It’s weeks in jars, maybe months, maybe years buried underground where it can ferment. And yet, despite this, I failed to realize that editing is the same way. (And sadly, publisher schedules don’t really line up in a way to allow this reality.) Editing needs time. You need time to think — and re-think — your book. Assess and reassess. You need time to break it down in your head, pulverizing it to its constituent parts. You need time to not only find out what’s wrong, but what’s right. At the beginning, at the fore of your edit, clarity isn’t there. (It’s why great editors are essential, as they can reduce the “cooking time,” so to speak. Shitty editors will either offer no help or worse, will only add turbidity to the water, delaying clarity further.) The second draft needs time just like the first does. You have to walk away. You have to think and think and think. Think while walking, think while showering, think while sitting in a tub of your own writer tears. Think. Obsess! All before you touch a damn thing.

6. Look At That Other Asshole. Another reason you need time? You need to emotionally decouple from the manuscript. You need time to disentangle your feelings about the first draft. I’ve said it before, and I will say it again: you need to get to the stage where it looks like some other asshole wrote the book. Once it feels like it’s not yours is the best time to edit it.

7. Notes Will Save You. Before I touch the draft, I open up Word, and I spew my jabber into the document. This is fairly stream-of-consciousness at first, though as I go, the notes tend to tighten up and become less me yelling at myself about this dumb book and more directives to fix it, which is key. It’s really just me talking through the book. If my agent or editor are involved at this point, I’ll clean up the notes, take some questions or thoughts, and bounce these ideas off them. It’s a good way to take whatever’s going on in the old skull-cave and get it out into the open, where I can see it, deal with it, fuck with it.

8. You’re Not Alone. Writing a first draft is a sojourn. It’s you against the elements. You’re Liam Neeson fighting wolves in the snow with his Liam Neesonness. But the second draft — hey, you don’t have to go at it alone. It’s one of my favorite parts of editing and revising — you get to bring other voices into it. You get to be challenged. Creative agitation is a necessary component of polishing your work and compressing that coal into — well, if not a diamond, then at least a fuel source to burn hot and burn bright. Light brings clarity.

9. Other People Are Not Automatically Wrong, And They’re Not Automatically Right. Here’s the one complicating factor over inviting other voices to participate in your work: your book is your precious and like Gollum you want to bludgeon anyone who dares try to steal your ring, or frankly, even that fish you’ve been gumming on for the last hour, you freak. Recognize that anyone offering notes or thoughts is not automatically wrong. And yet, they’re also not automatically right. You have to take their notes and do the same thing as with the rest of the draft: you have to sit on them like a bird on an egg. You have to think about them. Assess and reassess. Let your heart, head or gut have its say. Maybe the egg hatches. Maybe you eat it.

10. Identify The Big Breaks. Don’t worry about a copy-edit yet. That comes later — often, last. Don’t sit there and dwell on the persnickety shit. I mean, you can, if it makes you feel better — but right now, your revision needs to be focused on the developmental stuff. The content. It doesn’t matter if a painting on the wall is askew if that wall needs to come down. Find out where the story fails in the biggest, most dramatic ways. Those are your priority. And one of the ways to hack into that is to ask yourself some questions –

11. Does Everything Make Sense? Does it? Does it, really? The most visible, if not the most important, failure of a story is when it just doesn’t make sense. Some plot component sticks out like a dildo duct-taped to a pig’s head. We’ve all seen movies or read books where things just don’t… line up. “Wait, how did he get from Cleveland to the Moonbase in the same time it took Esmerelda to eat a sandwich?” Things feel forced or clumsy or unclear. Those are big (and often, easy to fix) problems. Find them. Fix them. Don’t excuse them.

12. Do The Characters All Have Agency? In the past, I have defined character agency as this: It is a demonstration of the character’s ability to make decisions and affect the story. This character has motivations all her own. She is active more than she is reactive. She pushes on the plot more than the plot pushes on her. Even better, the plot exists as a direct result of the character’s actions. With that definition in mind, re-read your story with an eye toward — is the plot external? Do the characters have agency? Do they have problems and goals and quests? Are these problems and goals and quests defining the plot, or is the plot defining them? (Note: it should be the first one.) Find the places too where you force the characters to act on behalf of the plot rather than themselves. Meaning, they’re dancing to a beat that’s not their own — you as the writer are so in love with some plot point you’re jamming them into it sideways in the hopes they’ll fit. They won’t. Give them the power. You want a storytelling mantra? I got your mantra right here: Characters are not architecture — they are architects.

13. Does It All Flow Toward The Theme? Your book has a theme. (Note: if you haven’t figured that out yet, well, now’s a good time.) It’s making an argument. It has ideas. It has a point-of-view — not just the characters, but the whole damn book. All should flow toward that theme and the questions it answers.

14. Repeat After Me: Nothing Is Fundamentally Broken. During editing, just as during writing, you will occasionally feel hopeless. You will flail. You will gesticulate in the void. Gibbering and wailing. It’s normal. We all get there. You will feel at times like, THIS IS BAD THIS BOOK IS DUMB IT IS IRREVOCABLY BROKEN AND I SHOULD JUST GO AND LEARN A TRADE SKILL LIKE FORGING BLADES OR CURRYING HORSES WHICH HEY BY THE WAY IS ABOUT GROOMING THE HORSE NOT COOKING IT IN A CURRY SAUCE, OOPS, GUESS I MESSED THAT UP, TOO, SORRY, HORSE. But during editing it is vital to realize: a lot may be broken, but everything can be fixed. It may take a lot of rejiggering and jangling and wangling. It may take some writing and rewriting. But you can do it. It’ll just take time.

15. A Schedule May Not Work. I have in the past advocated having a schedule when editing, just as you have a schedule when writing. It works, ennnh, sometimes? You can schedule writing fairly easily — “I will write 2,000 words a day like a good little writer,” and then you do it, and eventually you’re done, ta-da, have a cupcake. (*slaps cupcake out of your hand*) But editing does not so keenly fit into a regimen. It’s not enough to say, “I will edit five pages a day,” because though writing is formed of words and pages, editing is formed of problems. And the problems are of varying sizes. The best schedule I can tell you is this: set aside X number of hours a day to tackle the work until it’s done. That’s it. It’s not about words or pages, it’s just about fixing problems one by one, big and small. Find your process. Maybe it’s about re-outlining the work. Maybe it’s about just picking away at it. Maybe it’s a whole damn rewrite. You gotta do you. Find your tools and your method of repair and get to work.

16. Post-It Notes Are Your Pal. I like to take a couple Post-It notes and write on them some things I need to keep in mind — overarching problems that the book has. DAVE IS TOO MUCH OF A JERK. THE SEQUENCE WITH THE OCTOPUS NEEDS TO MAKE SENSE IN THE CONTEXT OF THE REST OF THE BOOK. THE THEME IS THAT BAD THINGS HAPPEN TO GOOD BEARS. Whatever. I write them down, I keep them hanging around — often dangling from the bottom of my monitor like a beard made of information — and as I edit, I return focus to them again and again just to see if everything is lining up to fix those problems.

16. Gain Power Over It, Like An Exorcist. The first change is the hardest. I don’t know why that is. I come to edit a book and I feel unsteady, unconfident — often the same way that I feel when starting a book fresh. I feel just born. Raw, abraded, burned by light. And the solution with your first draft is to write your first sentence, paragraph, then page. Once that happens, it’s like uncorking the bottle and letting the demons out. Editing works the same. You need to regain your power. You need your groove back. Make one change. Doesn’t need to be a big one, but make the damn change. Maybe it’s a little copy-edit, or you change one scene of dialogue, or whatever it is you do. Just get your fingerprints on it. It’s like one of those stupid puzzles where the pieces are all jumbled and it’s confusing and fuck that puzzle. But then you move one tile, and it’s like, well, this still sucks, but sure, sure, I’ll move a second tile, and next thing you know, you’re doing it. Of course, this is a terrible metaphor because I’m pretty sure I never finished a single one of those dumb puzzles and that they all ended up in the bin.

17. Min-Max That Monster. I sometimes treat editing like a game of chess against an invisible opponent. (Ironically, my opponent is the dumbass who wrote the first draft, so I’m just playing against an earlier version of myself.) And I always try to figure out how to solve a problem with the fewest moves possible. How can I fix an error with minimal changes? It’s not always possible to keep it small, but it’s amazing how once in a while you get a big problem that you can fix with just a few clever Bonsai cuts — or the addition of some dialogue or a scene. You can play this game too with other stories — you watch a movie, see what’s wrong, then ask yourself how would you fix those problems with the fewest moves available?

18. Seek Pieces That Don’t Echo. I’ve come to realize that a story isn’t a string of connected bits all lined up in a row. It’s not a sequence of events. It’s a series of echoes. Characters do things and say things and it creates consequences. Elements and objects appear, and they have weight and meaning inside the story. There are causes and there are effects. Each piece is a rock thrown into the water and the story is about the ripples — and how ripples reach the shore. What I mean is, when I write now I look for parts of the story that don’t echo. They have no ripples. This helps me more than the idea of kill your darlings, because honestly that was always a complicated chestnut. Here, it’s cleaner to say, what parts of your story don’t make ripples? What bits fail to reverberate? These pieces exist on their own. They don’t add to the music. It’s like the idea of Chekhov’s Gun — the gun that appears in the first act should go off by the third. This isn’t about a gun, not really. It’s about inserting an element that echoes throughout. Every pig needs a snout and a tail. Every element needs to sing for its supper.

19. Cut A Section Just To See — Or Add One, Instead. SOMETIMES YOU NEED TO BE BATMAN ASKING SUPERMAN IF HE BLEEDS. … wait, don’t do that, that’s dumb. What I mean is, if you’re reading your book, and you’re struggling with a section like you’re wrestling with a python, the answer might just be: cut it. Seriously, kill it. Save it! Put it aside, don’t send it into oblivion. But remove it and then read it again. Sit on that change, and see if the story is fundamentally changed by its loss. It may be improved. The opposite holds true, though, too: sometimes you haven’t added enough. Sometimes you’re wrestling with a section and you realize that you need a bridging component, or an additional scene to add context. That’s okay, too. It’s why I’m troubled by advice that says you should automatically cut like, 25% of your draft — no, no, no. Every story is different. And every writer has different deficiencies. Fix your story, not some mythical ideal of one.

20. Kill The Boring Parts. My advice for writing is the same for editing: skip the boring parts. This is easier to do in editing, actually, because when you’ve made it seem like some other asshole wrote this thing, you will be more keenly attuned to what drags on like a dead hippo pulled through the mud by an old tractor. Find the parts where your eyes glaze over. Are those parts necessary? No. Kill them. If that part is necessary, rewrite so it’s not dull as a stump.

21. Reality: Sometimes Your Second Draft Is Worse Than The First. Sometimes you’ll “fix” the draft only to have broken it further. This is a reality. It’s okay. We all take wrong turns. But you’ll need to do a third draft to unfuck the fucking you did. Sorry?

22. Reality: Sometimes Your Fixes Are Quick And Brutal. I am wont to say that writing is great because really you get as many do-overs and take-backs as you want. Life is often a one-draft proposition — but writing is as many as you need. Nnnyeah, except for the pro writer, who has fucking deadlines. You can wiggle around them a little, but deadlines are deadlines and eventually you have to stop writing and turn in a thing, and then again you have to stop revising and turn in the thing again. You have a stop date. Which means sometimes your fixes are inelegant bludgeoning attacks. And sometimes, those work better than you think. Go with it. Get it done. Sometimes you’re Mozart, sometimes you’re the Ramones. Sometimes it’s scalpel-cuts, sometimes you drop a washing machine on its head. Sorry?

23. Reality: You Might Have To Do It Again And Again. It took me five years to write my first published novel, Blackbirds. And it took a lot of drafts. I don’t even know how many. The early drafts look almost nothing like the final. Seriously, in one draft she ends up in Maine and gets a job and Ashley Gaynes is a guy working at a factory with her and — I mean, it goes off the fucking rails again and again, and I didn’t know how to fix it until one day I learned how to outline a novel and write a screenplay. Our journeys are weird, what can I say? Every book needs as many drafts as it needs. Some are aces out of the gate and just need a tickle and a polish. Others take five years of bashing your head against a wall until epiphany. Sorry?

24. Reality: It Won’t Edit Itself. It really won’t. Stare at it. Scowl at it. Yell at it all you like, it’s still not getting editing its owndamnself. You gotta get into those guts, get your hands bloody. The work is the work, hard as it is to do. Sorry?

25. Reality: This Is The Most Important Part. The art is in the arrangement. Editing is about that arrangement. There exist writers who don’t believe in second drafts, who don’t believe in editing, and these precious poodles are not people I understand. You are a stage magician and every stage magician practices the trick. They revise it. Just as a comedian practices and revises the routine — it might be good on the outset, but you want to sharpen, you want to tweak the timing, the emphasis, the word choice. That’s your book. It’s a big trick. A giant riddle or joke. It needs your hand. Editing and revising is more important than writing. Your subsequent drafts are more important than your first. That first draft is for you. The other drafts are for everyone else. So make them count. Do the work. This is the job.

P.S. you can do this

P.P.S. don’t panic

P.P.S.S. okay you can panic a little I won’t tell

P.P.S.S.S. *puts cupcake into your hand just to swat it to the ground*

* * *

INVASIVE:

“Think Thomas Harris’ Will Graham and Clarice Starling rolled into one and pitched on the knife’s edge of a scenario that makes Jurassic Park look like a carnival ride. Another rip-roaring, deeply paranoid thriller about the reasons to fear the future.” — Kirkus Reviews (starred review)

Out now where books are sold.

January 9, 2017

Macro Monday Gets A Little Frosty

That’s not a recent macro, but I figured given the white stuff that dumped upon a lot of you in the past few days (though we only got a couple inches at most), this macro was appropriate.

Not much else going on, really, of note.

Blackbirds, the first Miriam Black book, remains $1.99 for your e-machine: at B&N, Amazon, Apple, Kobo and Google Play. So, if you were looking for a cheap and easy way to dive into Miriam Black’s blood-soaked, nicotine-charred world of asphalt and motels and murder, well, there’s no price like the present one.

It is official, too, that the Chinese publisher Beijing White Horse Time procured the rights to publish the next three Miriam books — Thunderbird, The Raptor & The Wren, and Vultures in China. Woo!

Go forth and pin your week to the ground and slay the beast, folks.

January 6, 2017

Flash Fiction Challenge: Apocalypse Now!

AND WE’RE BACK.

It’s time to revivify these challenges, I think, and this time around, let’s lean hard into our current geopolitical poopshow and ponder THE APOCALYPSE.

Except, here’s the deal.

I don’t want you to write THE USUAL APOCALYPSE.

I want you to make one up you have not seen before.

A rare, strange, unparalleled apocalypse. Unexpected. Unwritten.

You have, ohhh, let’s say 1500 words to give us a glimpse of your brand new uniquely-you Apocalypse. Due on (dun dun dun) Friday the 13th, by noon EST. Post at your online space, drop a link in the comments below so we can all read it. Go forth and end the world, my friends, and write a compelling tale to go along with a fitting end.

January 4, 2017

I Gotcher Blackbirds! Blackbirds Here! Just A Buck-Ninety-Nine

DEAREST AUDIENCE,

I write to inform you of a recent change regarding my debut original novel, Blackbirds, which features the first adventure of the heroine, Miriam Black, a scalding cup of rat poison in human form. Miriam is a psychic and is able to see how and when you die simply by touching your skin to her skin. This has, quite clearly, left poor Miriam feeling less and less pleasant as regards humanity and the rest of its sweaty ilk.

That novel is presently on sale for a mere one dollar and ninety-nine pennies, and it is for sale at this price at B&N for your Nook, though you will also find it price-matched at Amazon and at Apple and yes, also at Kobo and even at something called Google Play. I do hope that if you have not yet enjoyed the Frisbee-to-the-face that is Miriam Black that you will choose to begin her venomous adventures here with the first book, with the consideration that oh my oh my, there are two more books published (Mockingbird and The Cormorant, respectively) and three more on the way (Thunderbird coming out next month, The Raptor & The Wren out by end of year, and the final book, Vultures, out at some point before your inevitable demise).

If you remain uncertain, please enjoy this book trailer.

I promise, it’s actually a very good trailer.

If you don’t enjoy the trailer, I will in fact compensate you for your lost time, as I am a chronomancer with power over the temporal threads that bind the universe. But please don’t spread that around as it causes me trouble.

Enjoy Blackbirds, should you endeavor to pluck it from the digital ether. If you were inclined to pre-order the newest, Thunderbird, I would be positively ebullient. Further, if you are caught up on the first three but have not yet read the novella called Interlude: Swallow that ties together Cormorant and Thunderbird, then behold the collection in which it sits: Three Slices.

See you on the other side, goodly folk! Ta!

With deepest disregard,

CHARLES Q. WENDIGO, THE THIRD

p.s. the art is by the mighty Galen Dara

January 3, 2017

Awkward Author Photo Contest: The Awkward Author Winners!

AND SO IT IS DONE.

The votes are tallied.

The awkwardness is codified and canonical.

Here then are the top four winners –

#14 (by a long shot), #22, then in a tight race, #27, and #15. #2 also came in close enough where I’m gonna just go ahead and count it as five winners as much as four, because those last three were one vote off apiece, and god only knows if I fucked up the vote count.

Congrats to you winners.

I mean, “congrats,” because c’mon. *side-eye*

YOU WINNER HUMANS, you need to email me at terribleminds at gmail dot com and gimme your deets. By which I mean, your mailing address so I can mail you a book.

Here, then, are the top five:

#14

#22

#27

#15

#2