LoraKim Joyner's Blog, page 2

September 5, 2019

Burning Love: A Parrot Shows How to Put Out Fires of Human Desire

This has been a year of fires in Latin America. Jarring our sense of well being and future hope for the planet, one headline after another warns of the dire consequences of very high level of forest burning in the Amazon this year. A neighboring country, where One Earth has parrot conservation projects, is also burning. As of the end of August, 91,429 acres had been burned in two locations in Paraguay. Other acreage charred has not been tabulated yet, such as the fires in San Luis National Park, whose flames and smoke we drove through last week.  Burning entrance to National Park San Luis seen through haze that makes the setting sun colors vibrant against the grey landscapeThesefires are related to the intense agricultural pressure on threatened habits, including cattle and soy, of which much of the soy goes to Asia to feed animals there for eventual slaughter. Human love for meat is "killing the planet."Love can also save the planet. When in Paraguay over the last 3 weeks, it was the parrot breeding season. I was outside for 12 days, all day, and nearly every day I was privileged to witness courtship and copulation behavior of parrots. The trees were full of avian eroticism! Their activities were not only beautiful, but powerful. These birds reminded me of the potential of human love, in all its various forms, that can cause us to move mountains, and put out the fires of our desires.

Burning entrance to National Park San Luis seen through haze that makes the setting sun colors vibrant against the grey landscapeThesefires are related to the intense agricultural pressure on threatened habits, including cattle and soy, of which much of the soy goes to Asia to feed animals there for eventual slaughter. Human love for meat is "killing the planet."Love can also save the planet. When in Paraguay over the last 3 weeks, it was the parrot breeding season. I was outside for 12 days, all day, and nearly every day I was privileged to witness courtship and copulation behavior of parrots. The trees were full of avian eroticism! Their activities were not only beautiful, but powerful. These birds reminded me of the potential of human love, in all its various forms, that can cause us to move mountains, and put out the fires of our desires. Two nanday parakeets matingAt times (okay most of the time) it seems as if the odds are long and hard against any kind of success. How indeed do we extinguish human desire soon enough, or at all? An ancient Buddhist tale offers us wisdom of how to go forward when the world is burning around us. It ends this way.......the little parrot says she has spotted a way [to put out the wildfire] so she must try.She wets her feathers in the river, fills a leaf cup with water, and flies back over the burning forest. Back and forth she flies carrying drops of water. Her feathers become charred, her claws crack, her eyes burn red as coals.A god looking down sees her. Other gods laugh at her foolishness, but this god changes into a great eagle, flies down, and tells her, as it’s hopeless, to turn back. She won’t listen but continues bringing drops of water. Seeing her selfless bravery, the god is overwhelmed and begins to weep. His tears put out the fire and heal all the animals, plants, and trees. Falling on the little parrot, the tears cause her charred feathers to grow back red as fire, blue as a river, green as a forest, yellow as sunlight.She is now a beautiful bird. The parrot flies happily over the healed forest she has saved.

Two nanday parakeets matingAt times (okay most of the time) it seems as if the odds are long and hard against any kind of success. How indeed do we extinguish human desire soon enough, or at all? An ancient Buddhist tale offers us wisdom of how to go forward when the world is burning around us. It ends this way.......the little parrot says she has spotted a way [to put out the wildfire] so she must try.She wets her feathers in the river, fills a leaf cup with water, and flies back over the burning forest. Back and forth she flies carrying drops of water. Her feathers become charred, her claws crack, her eyes burn red as coals.A god looking down sees her. Other gods laugh at her foolishness, but this god changes into a great eagle, flies down, and tells her, as it’s hopeless, to turn back. She won’t listen but continues bringing drops of water. Seeing her selfless bravery, the god is overwhelmed and begins to weep. His tears put out the fire and heal all the animals, plants, and trees. Falling on the little parrot, the tears cause her charred feathers to grow back red as fire, blue as a river, green as a forest, yellow as sunlight.She is now a beautiful bird. The parrot flies happily over the healed forest she has saved. Love causes us to grieve what we have lost, and to come together to work with great commitment to save what we can, even when it is hopeless. And it might just be that the spirit of broken hearts will heal us, and the earth.(To learn how to grieve and mourn, and turn this into committed actions, refer to our book, Nurturing Discussions and Practices.)

Love causes us to grieve what we have lost, and to come together to work with great commitment to save what we can, even when it is hopeless. And it might just be that the spirit of broken hearts will heal us, and the earth.(To learn how to grieve and mourn, and turn this into committed actions, refer to our book, Nurturing Discussions and Practices.)

Burning entrance to National Park San Luis seen through haze that makes the setting sun colors vibrant against the grey landscapeThesefires are related to the intense agricultural pressure on threatened habits, including cattle and soy, of which much of the soy goes to Asia to feed animals there for eventual slaughter. Human love for meat is "killing the planet."Love can also save the planet. When in Paraguay over the last 3 weeks, it was the parrot breeding season. I was outside for 12 days, all day, and nearly every day I was privileged to witness courtship and copulation behavior of parrots. The trees were full of avian eroticism! Their activities were not only beautiful, but powerful. These birds reminded me of the potential of human love, in all its various forms, that can cause us to move mountains, and put out the fires of our desires.

Burning entrance to National Park San Luis seen through haze that makes the setting sun colors vibrant against the grey landscapeThesefires are related to the intense agricultural pressure on threatened habits, including cattle and soy, of which much of the soy goes to Asia to feed animals there for eventual slaughter. Human love for meat is "killing the planet."Love can also save the planet. When in Paraguay over the last 3 weeks, it was the parrot breeding season. I was outside for 12 days, all day, and nearly every day I was privileged to witness courtship and copulation behavior of parrots. The trees were full of avian eroticism! Their activities were not only beautiful, but powerful. These birds reminded me of the potential of human love, in all its various forms, that can cause us to move mountains, and put out the fires of our desires. Two nanday parakeets matingAt times (okay most of the time) it seems as if the odds are long and hard against any kind of success. How indeed do we extinguish human desire soon enough, or at all? An ancient Buddhist tale offers us wisdom of how to go forward when the world is burning around us. It ends this way.......the little parrot says she has spotted a way [to put out the wildfire] so she must try.She wets her feathers in the river, fills a leaf cup with water, and flies back over the burning forest. Back and forth she flies carrying drops of water. Her feathers become charred, her claws crack, her eyes burn red as coals.A god looking down sees her. Other gods laugh at her foolishness, but this god changes into a great eagle, flies down, and tells her, as it’s hopeless, to turn back. She won’t listen but continues bringing drops of water. Seeing her selfless bravery, the god is overwhelmed and begins to weep. His tears put out the fire and heal all the animals, plants, and trees. Falling on the little parrot, the tears cause her charred feathers to grow back red as fire, blue as a river, green as a forest, yellow as sunlight.She is now a beautiful bird. The parrot flies happily over the healed forest she has saved.

Two nanday parakeets matingAt times (okay most of the time) it seems as if the odds are long and hard against any kind of success. How indeed do we extinguish human desire soon enough, or at all? An ancient Buddhist tale offers us wisdom of how to go forward when the world is burning around us. It ends this way.......the little parrot says she has spotted a way [to put out the wildfire] so she must try.She wets her feathers in the river, fills a leaf cup with water, and flies back over the burning forest. Back and forth she flies carrying drops of water. Her feathers become charred, her claws crack, her eyes burn red as coals.A god looking down sees her. Other gods laugh at her foolishness, but this god changes into a great eagle, flies down, and tells her, as it’s hopeless, to turn back. She won’t listen but continues bringing drops of water. Seeing her selfless bravery, the god is overwhelmed and begins to weep. His tears put out the fire and heal all the animals, plants, and trees. Falling on the little parrot, the tears cause her charred feathers to grow back red as fire, blue as a river, green as a forest, yellow as sunlight.She is now a beautiful bird. The parrot flies happily over the healed forest she has saved. Love causes us to grieve what we have lost, and to come together to work with great commitment to save what we can, even when it is hopeless. And it might just be that the spirit of broken hearts will heal us, and the earth.(To learn how to grieve and mourn, and turn this into committed actions, refer to our book, Nurturing Discussions and Practices.)

Love causes us to grieve what we have lost, and to come together to work with great commitment to save what we can, even when it is hopeless. And it might just be that the spirit of broken hearts will heal us, and the earth.(To learn how to grieve and mourn, and turn this into committed actions, refer to our book, Nurturing Discussions and Practices.)

Published on September 05, 2019 09:24

August 13, 2019

Making the Impossible Possible - Food Choices Save Parrots and Planets

The Earth has been telling us, for decades (and longer), "I told you so! You can't keep on the way you are without dire consequences." Last week a report came out from the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, confirming this refrain that echoes through earth's devastated habitats and human communities.Specifically, as reported by The Guardian..."The report, approved by the world’s governments, makes clear that humanity faces a stark choice between a vicious or virtuous circle. Continued destruction of forests and huge emissions from cattle and other intensive farming practices will intensify the climate crisis, making the impacts on land still worse. However, action now to allow soils and forests to regenerate and store carbon, and to cut meat consumption by people and food waste, could play a big role in tackling the climate crisis, the report says."A perverse part of me feels vindicated with this report, internalizing my own "I told you so" energy. For years I had been sounding the alarm about what agricultural practices and overconsumption are doing to the planet and her beings. But I don't feel better, even in "being right." I would rather have been wrong. Guatemalan cattle ranch where we had parrot conservation project in the 1990s When I lived in Guatemala leading parrot conservation efforts I worked a lot on cattle ranches, the forest long gone due to agricultural practices. Seeing what cattle did to the people and the habitat, which was largely an export business that took resources from the ecosystems and communities and shipped them out to other countries, I vowed to quit eating beef in 1995. The UN report warns humans to cut back on eating all animal products because of the methane ruminant animals (cows, goats, sheep) produce, the cutting of trees to provide pasture, the pollution of the manure, and the high use of water to produce the equivalent amount of protein rather through plant sources. All these contribute to climate change and habitat degradation. Part of my reasoning was also the cruelty in intense agricultural practices that produce the animal products in the USA.

Guatemalan cattle ranch where we had parrot conservation project in the 1990s When I lived in Guatemala leading parrot conservation efforts I worked a lot on cattle ranches, the forest long gone due to agricultural practices. Seeing what cattle did to the people and the habitat, which was largely an export business that took resources from the ecosystems and communities and shipped them out to other countries, I vowed to quit eating beef in 1995. The UN report warns humans to cut back on eating all animal products because of the methane ruminant animals (cows, goats, sheep) produce, the cutting of trees to provide pasture, the pollution of the manure, and the high use of water to produce the equivalent amount of protein rather through plant sources. All these contribute to climate change and habitat degradation. Part of my reasoning was also the cruelty in intense agricultural practices that produce the animal products in the USA. What's left of the Atlantic forest in Paraguay I am going to Paraguay this coming week to work on parrot conservation, and there is only 7% of the Atlantic forest habitat left, due to cattle, as well as soy monoculture agribusiness that ships the majority of the soy to China to feed pigs for human consumption. There are few parrots left in the area, including the endangered vinaceous amazon parrot, and the larger macaws. The human villages that once lived here are long gone. Cattle is also quickly taking out the Chaco ecosystems in Paraguaywith nearly 500,000 acres disappearing a year.

What's left of the Atlantic forest in Paraguay I am going to Paraguay this coming week to work on parrot conservation, and there is only 7% of the Atlantic forest habitat left, due to cattle, as well as soy monoculture agribusiness that ships the majority of the soy to China to feed pigs for human consumption. There are few parrots left in the area, including the endangered vinaceous amazon parrot, and the larger macaws. The human villages that once lived here are long gone. Cattle is also quickly taking out the Chaco ecosystems in Paraguaywith nearly 500,000 acres disappearing a year. Less than 100 vinaceous amazon parrots are left in Paraguay. They hold out in forest patches isolated by agricultural fieldsI also work on the Atlantic coast of Guatemala and Honduras with the very endangered yellow-headed parrot. Illegal poaching to supply pets for the international wildlife market is the big culprit. However, the draining of swamps, largely illegal, to put in African palm tracts wipes out more and more of the few remaining nests every year. The cattle in this region removed most of the forest long ago.

Less than 100 vinaceous amazon parrots are left in Paraguay. They hold out in forest patches isolated by agricultural fieldsI also work on the Atlantic coast of Guatemala and Honduras with the very endangered yellow-headed parrot. Illegal poaching to supply pets for the international wildlife market is the big culprit. However, the draining of swamps, largely illegal, to put in African palm tracts wipes out more and more of the few remaining nests every year. The cattle in this region removed most of the forest long ago.  Yellow-headed parrot perched atop one of the few trees in the middle of a cattle field in Honduras on the Atlantic CoastAfrican palm and cattle are also carving up the Moskitia forest in Honduras where we work with the endangered scarlet and great green macaw, as well as the yellow-naped parrot. Over 30% of the forest has been lost in the last 15 years.

Yellow-headed parrot perched atop one of the few trees in the middle of a cattle field in Honduras on the Atlantic CoastAfrican palm and cattle are also carving up the Moskitia forest in Honduras where we work with the endangered scarlet and great green macaw, as well as the yellow-naped parrot. Over 30% of the forest has been lost in the last 15 years.  Newly planted African palms on the Atlantic Coast of Honduras (photo by Lon & Queta) Producing animal protein at the levels we are now for over consuming human societies, is killing the planet, and the wildlife and human communities that depend on the earth.What can be done? You might think, as many do, that it is impossible to reduce human's appetite that leads to biodiversity loss and climate change.But there is one thing that most of us on this planet can do. The report states that those in the over consuming societies where protein can be obtained through plant sources should cut back on animal protein consumption. This is getting easier and easier to do in the USA.For instance, the "Impossible Whopper" was released by Burger King last week. I admit to having 3 of them since then. They do make for a tasty burger. I am not entirely happy with this item, because it does contain eggs, and egg production is also harmful for the environment and for the chickens (and for chicken farm workers). It is also high in fat and salt. So it might not be the best option for saving your health and the planet, but it, like other diet choices, can have a significant impact.

Newly planted African palms on the Atlantic Coast of Honduras (photo by Lon & Queta) Producing animal protein at the levels we are now for over consuming human societies, is killing the planet, and the wildlife and human communities that depend on the earth.What can be done? You might think, as many do, that it is impossible to reduce human's appetite that leads to biodiversity loss and climate change.But there is one thing that most of us on this planet can do. The report states that those in the over consuming societies where protein can be obtained through plant sources should cut back on animal protein consumption. This is getting easier and easier to do in the USA.For instance, the "Impossible Whopper" was released by Burger King last week. I admit to having 3 of them since then. They do make for a tasty burger. I am not entirely happy with this item, because it does contain eggs, and egg production is also harmful for the environment and for the chickens (and for chicken farm workers). It is also high in fat and salt. So it might not be the best option for saving your health and the planet, but it, like other diet choices, can have a significant impact. An Impossible Burger (photo by Dilu)If you choose this burger for instance, over others, Impossible Foodsclaims that 87% less water and 96% less land is used, and 89% less greenhouse gases are produced than eating an equivalent burger made of beef.The impossible is becoming possible. You, no matter where you live, can make daily choices that can save a parrot, and eventually, contribute to saving the planet.We can do this people! For we love the earth, this I know.

An Impossible Burger (photo by Dilu)If you choose this burger for instance, over others, Impossible Foodsclaims that 87% less water and 96% less land is used, and 89% less greenhouse gases are produced than eating an equivalent burger made of beef.The impossible is becoming possible. You, no matter where you live, can make daily choices that can save a parrot, and eventually, contribute to saving the planet.We can do this people! For we love the earth, this I know.

Guatemalan cattle ranch where we had parrot conservation project in the 1990s When I lived in Guatemala leading parrot conservation efforts I worked a lot on cattle ranches, the forest long gone due to agricultural practices. Seeing what cattle did to the people and the habitat, which was largely an export business that took resources from the ecosystems and communities and shipped them out to other countries, I vowed to quit eating beef in 1995. The UN report warns humans to cut back on eating all animal products because of the methane ruminant animals (cows, goats, sheep) produce, the cutting of trees to provide pasture, the pollution of the manure, and the high use of water to produce the equivalent amount of protein rather through plant sources. All these contribute to climate change and habitat degradation. Part of my reasoning was also the cruelty in intense agricultural practices that produce the animal products in the USA.

Guatemalan cattle ranch where we had parrot conservation project in the 1990s When I lived in Guatemala leading parrot conservation efforts I worked a lot on cattle ranches, the forest long gone due to agricultural practices. Seeing what cattle did to the people and the habitat, which was largely an export business that took resources from the ecosystems and communities and shipped them out to other countries, I vowed to quit eating beef in 1995. The UN report warns humans to cut back on eating all animal products because of the methane ruminant animals (cows, goats, sheep) produce, the cutting of trees to provide pasture, the pollution of the manure, and the high use of water to produce the equivalent amount of protein rather through plant sources. All these contribute to climate change and habitat degradation. Part of my reasoning was also the cruelty in intense agricultural practices that produce the animal products in the USA. What's left of the Atlantic forest in Paraguay I am going to Paraguay this coming week to work on parrot conservation, and there is only 7% of the Atlantic forest habitat left, due to cattle, as well as soy monoculture agribusiness that ships the majority of the soy to China to feed pigs for human consumption. There are few parrots left in the area, including the endangered vinaceous amazon parrot, and the larger macaws. The human villages that once lived here are long gone. Cattle is also quickly taking out the Chaco ecosystems in Paraguaywith nearly 500,000 acres disappearing a year.

What's left of the Atlantic forest in Paraguay I am going to Paraguay this coming week to work on parrot conservation, and there is only 7% of the Atlantic forest habitat left, due to cattle, as well as soy monoculture agribusiness that ships the majority of the soy to China to feed pigs for human consumption. There are few parrots left in the area, including the endangered vinaceous amazon parrot, and the larger macaws. The human villages that once lived here are long gone. Cattle is also quickly taking out the Chaco ecosystems in Paraguaywith nearly 500,000 acres disappearing a year. Less than 100 vinaceous amazon parrots are left in Paraguay. They hold out in forest patches isolated by agricultural fieldsI also work on the Atlantic coast of Guatemala and Honduras with the very endangered yellow-headed parrot. Illegal poaching to supply pets for the international wildlife market is the big culprit. However, the draining of swamps, largely illegal, to put in African palm tracts wipes out more and more of the few remaining nests every year. The cattle in this region removed most of the forest long ago.

Less than 100 vinaceous amazon parrots are left in Paraguay. They hold out in forest patches isolated by agricultural fieldsI also work on the Atlantic coast of Guatemala and Honduras with the very endangered yellow-headed parrot. Illegal poaching to supply pets for the international wildlife market is the big culprit. However, the draining of swamps, largely illegal, to put in African palm tracts wipes out more and more of the few remaining nests every year. The cattle in this region removed most of the forest long ago.  Yellow-headed parrot perched atop one of the few trees in the middle of a cattle field in Honduras on the Atlantic CoastAfrican palm and cattle are also carving up the Moskitia forest in Honduras where we work with the endangered scarlet and great green macaw, as well as the yellow-naped parrot. Over 30% of the forest has been lost in the last 15 years.

Yellow-headed parrot perched atop one of the few trees in the middle of a cattle field in Honduras on the Atlantic CoastAfrican palm and cattle are also carving up the Moskitia forest in Honduras where we work with the endangered scarlet and great green macaw, as well as the yellow-naped parrot. Over 30% of the forest has been lost in the last 15 years.  Newly planted African palms on the Atlantic Coast of Honduras (photo by Lon & Queta) Producing animal protein at the levels we are now for over consuming human societies, is killing the planet, and the wildlife and human communities that depend on the earth.What can be done? You might think, as many do, that it is impossible to reduce human's appetite that leads to biodiversity loss and climate change.But there is one thing that most of us on this planet can do. The report states that those in the over consuming societies where protein can be obtained through plant sources should cut back on animal protein consumption. This is getting easier and easier to do in the USA.For instance, the "Impossible Whopper" was released by Burger King last week. I admit to having 3 of them since then. They do make for a tasty burger. I am not entirely happy with this item, because it does contain eggs, and egg production is also harmful for the environment and for the chickens (and for chicken farm workers). It is also high in fat and salt. So it might not be the best option for saving your health and the planet, but it, like other diet choices, can have a significant impact.

Newly planted African palms on the Atlantic Coast of Honduras (photo by Lon & Queta) Producing animal protein at the levels we are now for over consuming human societies, is killing the planet, and the wildlife and human communities that depend on the earth.What can be done? You might think, as many do, that it is impossible to reduce human's appetite that leads to biodiversity loss and climate change.But there is one thing that most of us on this planet can do. The report states that those in the over consuming societies where protein can be obtained through plant sources should cut back on animal protein consumption. This is getting easier and easier to do in the USA.For instance, the "Impossible Whopper" was released by Burger King last week. I admit to having 3 of them since then. They do make for a tasty burger. I am not entirely happy with this item, because it does contain eggs, and egg production is also harmful for the environment and for the chickens (and for chicken farm workers). It is also high in fat and salt. So it might not be the best option for saving your health and the planet, but it, like other diet choices, can have a significant impact. An Impossible Burger (photo by Dilu)If you choose this burger for instance, over others, Impossible Foodsclaims that 87% less water and 96% less land is used, and 89% less greenhouse gases are produced than eating an equivalent burger made of beef.The impossible is becoming possible. You, no matter where you live, can make daily choices that can save a parrot, and eventually, contribute to saving the planet.We can do this people! For we love the earth, this I know.

An Impossible Burger (photo by Dilu)If you choose this burger for instance, over others, Impossible Foodsclaims that 87% less water and 96% less land is used, and 89% less greenhouse gases are produced than eating an equivalent burger made of beef.The impossible is becoming possible. You, no matter where you live, can make daily choices that can save a parrot, and eventually, contribute to saving the planet.We can do this people! For we love the earth, this I know.

Published on August 13, 2019 07:59

August 6, 2019

Wild Until Death: Praying to Birds

When I was a child, my parents required that I kneel before my bed and say my nightly prayers. Raised in a Christian tradition, the formula was to ask God for forgiveness so that I and my family could go to heaven. I changed the script a bit and instead prayed:Dear God, please take me into heaven. I am afraid of dying. But I don't want to go to heaven without the birds. Could you please send them to heaven too? If not, then I don't want to go either.

When I was a child, my parents required that I kneel before my bed and say my nightly prayers. Raised in a Christian tradition, the formula was to ask God for forgiveness so that I and my family could go to heaven. I changed the script a bit and instead prayed:Dear God, please take me into heaven. I am afraid of dying. But I don't want to go to heaven without the birds. Could you please send them to heaven too? If not, then I don't want to go either. Bird with Buddhist prayer flags (photo by Niklassletteland)Now that I am older, my orientation has shifted, perhaps more to a buddhist sensibility and reflects my years as a Unitarian Universalist minister. I realize that birds are heaven, as is this moment, now, with all the beautiful life around me. The problem is that I stumble with my lack of awareness and acceptance of this very moment's harsh beauty, which also contains countless deaths and suffering. But underneath this understanding, the recipe of my childhood's sense of salvation hasn't changed all that much. One can't get to heaven without death, but in this case it is the acceptance of death that is the gateway. By embracing death we erase any false lines of separation between us and birds, and the rest of nature, and are in turn embraced by the Whole of Life, and Death.I have seen so many birds die, their fragile bodies warped, and then woven into the life that arises from their bodies mixed with the soil and their beauty splashed across human consciousness. The way of bird life is death, and I want to go where the birds go. Recently we were surveying parrot populations on Ometepe Island, Nicaragua, and the entryway to one counting location up on the Maderas volcano was through a cemetery. It reminded me that to be with birds we have to journey through death.

Bird with Buddhist prayer flags (photo by Niklassletteland)Now that I am older, my orientation has shifted, perhaps more to a buddhist sensibility and reflects my years as a Unitarian Universalist minister. I realize that birds are heaven, as is this moment, now, with all the beautiful life around me. The problem is that I stumble with my lack of awareness and acceptance of this very moment's harsh beauty, which also contains countless deaths and suffering. But underneath this understanding, the recipe of my childhood's sense of salvation hasn't changed all that much. One can't get to heaven without death, but in this case it is the acceptance of death that is the gateway. By embracing death we erase any false lines of separation between us and birds, and the rest of nature, and are in turn embraced by the Whole of Life, and Death.I have seen so many birds die, their fragile bodies warped, and then woven into the life that arises from their bodies mixed with the soil and their beauty splashed across human consciousness. The way of bird life is death, and I want to go where the birds go. Recently we were surveying parrot populations on Ometepe Island, Nicaragua, and the entryway to one counting location up on the Maderas volcano was through a cemetery. It reminded me that to be with birds we have to journey through death. Entry point to counting up on Maderas volcanoAs my eyes followed the counters stepping through the graveyard to climb the slopes, I felt a relief from any sense of aloneness on this planet, or despair that so many beings die tragically, uselessly. I recalled a poem by Terry Tempest Williams:“I pray to the birds. I pray to the birds because I believe they will carry the messages of my heart upward. I pray to them because I believe in their existence, the way their songs begin and end each day—the invocations and benedictions of Earth. I pray to the birds because they remind me of what I love rather than what I fear. And at the end of my prayers, they teach me how to listen.”Each time I am at my own counting point, I raise my eyes to the heavens and to the birds. In counting them and in all my conservation work, which is like a prayer, I offer to them and to life:Please dear birds, take me with you. Don't leave me alone in a world of my own human construction and desires. May the soft animal of my body love all that it can, and like you, may I be wild until death.

Entry point to counting up on Maderas volcanoAs my eyes followed the counters stepping through the graveyard to climb the slopes, I felt a relief from any sense of aloneness on this planet, or despair that so many beings die tragically, uselessly. I recalled a poem by Terry Tempest Williams:“I pray to the birds. I pray to the birds because I believe they will carry the messages of my heart upward. I pray to them because I believe in their existence, the way their songs begin and end each day—the invocations and benedictions of Earth. I pray to the birds because they remind me of what I love rather than what I fear. And at the end of my prayers, they teach me how to listen.”Each time I am at my own counting point, I raise my eyes to the heavens and to the birds. In counting them and in all my conservation work, which is like a prayer, I offer to them and to life:Please dear birds, take me with you. Don't leave me alone in a world of my own human construction and desires. May the soft animal of my body love all that it can, and like you, may I be wild until death.

Published on August 06, 2019 08:18

July 30, 2019

Parrots are People Too

Kea parrot of New Zealand: One of the smartest parrots, and often considered very human-likeIn my many years of being a wildlife veterinarian and conservationist, I have often gotten asked, "Why spend so much time on humans when nonhumans need so much help?" Similarly, as a Unitarian Universalist minister I get asked, "Why spend so much time on nonhumans when humans need so much?"My answer comes from a lifetime of experience, my understanding of intersectional justice, and also my personal worldview. Life is an interconnected whole, and if we help relieve oppression or injustice in one location by getting at the root causes of domination, then we are helping all beings. I also know that humans need a functional and flourishing planet, which requires the health of individual beings and their ecosystems, and that nonhumans need humans to flourish, because if they don't, humans will continue to have to make hard choices that threaten the viability and health of individuals and ecosystems.I have also seen how a gestalt of promoting interconnected well being comes together in organizations and individuals who have as their foundation the well being of all animals, human or otherwise. A recent chapter in Human Rights Quarterly, "Animals Are People Too: Explaining Variation in Respect for Animal Rights," studied and expounded on this connection. They found a strong link between human and animal rights at the individual level, as well as at the US state policy level. In other words, if people or states were focusing more on human rights, they were also focusing more on animal rights.One Earth Conservation is one of many organizations that see the work of wildlife conservation as being fundamentally about linking human rights with animal rights. Freedom for one, results in freedom for the other. This is not the freedom to over consume or meet every desire, but being liberated from cultural limitations that weave us all into an unnecessary web of harm. We cannot help others to save their parrots without working with the people to save themselves, trying to reduce harm wherever we can. Conservationists more and more are striving for nonhuman well being, while also working for human well being. We need more people moving into this emerging paradigm of holding of value the well being and needs of every individual within the beautiful whole, because unfortunately, the older understanding persists as: It is a competition; If you take care of nonhumans you are basically devaluing humans, and vice versa.It turns out that this slowly diminishing framework of approaching planetary and community health is not only not true, but also potentially damaging to humans, nonhumans, and ecosystems. A forest without parrots, who are seed dispersers, is less diverse. A less diverse and more unhealthy forest, has less wildlife and less resilience against climate change and human interference. We need healthy forests for our water, for our air, for wildlife we depend on, for our climate which supports our agriculture and body health, and for our spiritual health. If we only concern ourselves with humans, we lose the forest and our parrots and other wildlife. And if we lose them, we lose everything.My concern is that the old way won't fade quick enough to save the planet so we can set into action individual behavior and policies based on seeing the interconnection of all beings' worth and needs. We are on the brink, so let's think, hard, love deeply, and act concretely and quickly.If you'd like to know more about the intersections of human and animal well being, visit the website, The Freedom Project, where we assert that none are free until all are free.

Kea parrot of New Zealand: One of the smartest parrots, and often considered very human-likeIn my many years of being a wildlife veterinarian and conservationist, I have often gotten asked, "Why spend so much time on humans when nonhumans need so much help?" Similarly, as a Unitarian Universalist minister I get asked, "Why spend so much time on nonhumans when humans need so much?"My answer comes from a lifetime of experience, my understanding of intersectional justice, and also my personal worldview. Life is an interconnected whole, and if we help relieve oppression or injustice in one location by getting at the root causes of domination, then we are helping all beings. I also know that humans need a functional and flourishing planet, which requires the health of individual beings and their ecosystems, and that nonhumans need humans to flourish, because if they don't, humans will continue to have to make hard choices that threaten the viability and health of individuals and ecosystems.I have also seen how a gestalt of promoting interconnected well being comes together in organizations and individuals who have as their foundation the well being of all animals, human or otherwise. A recent chapter in Human Rights Quarterly, "Animals Are People Too: Explaining Variation in Respect for Animal Rights," studied and expounded on this connection. They found a strong link between human and animal rights at the individual level, as well as at the US state policy level. In other words, if people or states were focusing more on human rights, they were also focusing more on animal rights.One Earth Conservation is one of many organizations that see the work of wildlife conservation as being fundamentally about linking human rights with animal rights. Freedom for one, results in freedom for the other. This is not the freedom to over consume or meet every desire, but being liberated from cultural limitations that weave us all into an unnecessary web of harm. We cannot help others to save their parrots without working with the people to save themselves, trying to reduce harm wherever we can. Conservationists more and more are striving for nonhuman well being, while also working for human well being. We need more people moving into this emerging paradigm of holding of value the well being and needs of every individual within the beautiful whole, because unfortunately, the older understanding persists as: It is a competition; If you take care of nonhumans you are basically devaluing humans, and vice versa.It turns out that this slowly diminishing framework of approaching planetary and community health is not only not true, but also potentially damaging to humans, nonhumans, and ecosystems. A forest without parrots, who are seed dispersers, is less diverse. A less diverse and more unhealthy forest, has less wildlife and less resilience against climate change and human interference. We need healthy forests for our water, for our air, for wildlife we depend on, for our climate which supports our agriculture and body health, and for our spiritual health. If we only concern ourselves with humans, we lose the forest and our parrots and other wildlife. And if we lose them, we lose everything.My concern is that the old way won't fade quick enough to save the planet so we can set into action individual behavior and policies based on seeing the interconnection of all beings' worth and needs. We are on the brink, so let's think, hard, love deeply, and act concretely and quickly.If you'd like to know more about the intersections of human and animal well being, visit the website, The Freedom Project, where we assert that none are free until all are free.

Published on July 30, 2019 10:35

July 25, 2019

We Count Them Because We Count on Them

The endangered yellow-naped parrot we were countingI have written before about how we count parrots in parrot conservation because they count on us. If we know where the wild parrots are (and mostly are not) we can figure out how and where to employ conservation efforts, which many parrots, the most endangered group of birds, need. Counting them also helps humans, as I witnessed this past week in Nicaragua.

The endangered yellow-naped parrot we were countingI have written before about how we count parrots in parrot conservation because they count on us. If we know where the wild parrots are (and mostly are not) we can figure out how and where to employ conservation efforts, which many parrots, the most endangered group of birds, need. Counting them also helps humans, as I witnessed this past week in Nicaragua. to get to Ometepe one takes a ferry which is coming into stormy Ometepe. The tropical wave of storms was threatening our counting week, because birds move differently when it is raining and blowing.

to get to Ometepe one takes a ferry which is coming into stormy Ometepe. The tropical wave of storms was threatening our counting week, because birds move differently when it is raining and blowing. The counting team before we head out on the first dayI was on Ometepe Island working with a group of 19 young conservationists to do the annual census of parrots. We were trying something not ever done before, at least by me. Where normally we counted only one region consisting of 4-6 individual counting points, we were now spread over 4 regions with 16 total points. Logistics were quite complex. How do you move this many people so that every single person is in place to count all parrots from 4:30 – 6:30 p.m.? How can you train all of them well enough so that they all use the same methodology and decision parameters to place birds into categories of species and flock size? Finally, how is there enough time the next day to help each person and each group analyze the flight patterns of birds to rule out duplicate sightings within the region, and between regions?e met for 5 days – starting at 1 p.m. We trained (photos below), reviewed methodology, and summarized the previous evening’s counts.

The counting team before we head out on the first dayI was on Ometepe Island working with a group of 19 young conservationists to do the annual census of parrots. We were trying something not ever done before, at least by me. Where normally we counted only one region consisting of 4-6 individual counting points, we were now spread over 4 regions with 16 total points. Logistics were quite complex. How do you move this many people so that every single person is in place to count all parrots from 4:30 – 6:30 p.m.? How can you train all of them well enough so that they all use the same methodology and decision parameters to place birds into categories of species and flock size? Finally, how is there enough time the next day to help each person and each group analyze the flight patterns of birds to rule out duplicate sightings within the region, and between regions?e met for 5 days – starting at 1 p.m. We trained (photos below), reviewed methodology, and summarized the previous evening’s counts.

Then at 3:30 p.m. we all dispersed to our assigned count locations I ended up in La Palma behind the community bar. Another ended up on a dock in Merida. One was near a pool at a resort, and another atop a building with a Jacuzzi. Others had to walk and far up the volcanoes to get to the open view necessary in parrot counting.

Then at 3:30 p.m. we all dispersed to our assigned count locations I ended up in La Palma behind the community bar. Another ended up on a dock in Merida. One was near a pool at a resort, and another atop a building with a Jacuzzi. Others had to walk and far up the volcanoes to get to the open view necessary in parrot counting. Motorcycles parked and ready to take the team out, as is Harry, our trusted drive (below)

Motorcycles parked and ready to take the team out, as is Harry, our trusted drive (below)

My spot for two nights was a bar in La Palma with a gorgeous view of Lake Cocibolca (above), and various other species keeping me company when the parrots flying over were scare

My spot for two nights was a bar in La Palma with a gorgeous view of Lake Cocibolca (above), and various other species keeping me company when the parrots flying over were scare The first evening everyone in each of the 4 regions counted together for training purposes. The next, each region had only two groups, again for training and for consistency. Then, the afternoon came when there were 4 points per region, and except for 3 points, everyone was by themselves, tracking hundreds of parrots and marking their species, time of flight, direction f flight, size of flock, altitude, distance, and vocalizations. Some points had up to 5 pages of observations, and a detailed map as well. I wondered if we were attempting the impossible. And then the improbable happened. Commitment to the process and the parrots broke through and bound us all together.

The first evening everyone in each of the 4 regions counted together for training purposes. The next, each region had only two groups, again for training and for consistency. Then, the afternoon came when there were 4 points per region, and except for 3 points, everyone was by themselves, tracking hundreds of parrots and marking their species, time of flight, direction f flight, size of flock, altitude, distance, and vocalizations. Some points had up to 5 pages of observations, and a detailed map as well. I wondered if we were attempting the impossible. And then the improbable happened. Commitment to the process and the parrots broke through and bound us all together.

I saw it in the first evening of individual counts as we picked up people in the dark in my region, La Palma (photos above at point #4 and entire La Palma team training together). In the back of the truck, counters used their phones flashlights to highlight their observations, not willing to wait until the next day to share what they had seen. “Did you see parents feeding their recently fledged chicks?” “Did you see that large rowdy group of juveniles?” “Did you know that I almost stepped on a coral snake?” “Wow, was the wind and rain bad at your location as well?”

I saw it in the first evening of individual counts as we picked up people in the dark in my region, La Palma (photos above at point #4 and entire La Palma team training together). In the back of the truck, counters used their phones flashlights to highlight their observations, not willing to wait until the next day to share what they had seen. “Did you see parents feeding their recently fledged chicks?” “Did you see that large rowdy group of juveniles?” “Did you know that I almost stepped on a coral snake?” “Wow, was the wind and rain bad at your location as well?”

Typical data sheets and the challenge to count every bird, only onceThese were just general observations. The detailed work comes the next day when each group went minute by minute, species by species, individual parrot by individual parrot to mark them as “counted” and to remove any birds observed by another transect point. It became a game to see if we could “rob” other counters of their birds, raising our numbers and decreasing theirs. “Those are mine, I saw them first!”

Typical data sheets and the challenge to count every bird, only onceThese were just general observations. The detailed work comes the next day when each group went minute by minute, species by species, individual parrot by individual parrot to mark them as “counted” and to remove any birds observed by another transect point. It became a game to see if we could “rob” other counters of their birds, raising our numbers and decreasing theirs. “Those are mine, I saw them first!” A pair of Pacific parakeets on watch outside their nest this past weekThis methodology, “Fixed Transects for Determining the Minimum Number of Distinct Individuals” is not easy. In our most parrot populous area there were nearly 1200 Pacific parakeets, and over 700 hundred yellow-naped and red-lored parrots. For each parrot we had to ask, “Whose are they? Who left us? Who came to us? Did we honor what we saw? Did we check our assumptions, observations, and math with others?” Our questions were like a congregated spiritual discovery, where we produced a holy result where every individual person and parrot mattered, and was worthy of our focus and attention. The maps we drew showed not just our location, but every flight represented by an arrow. These flight paths intersected in and out like a spider’s web or threads on a loom. In making these maps, we wove together the rends in the web of life caused by human exceptionalism and our false sense of separation. Instead we wove our species in among the worthy others.

A pair of Pacific parakeets on watch outside their nest this past weekThis methodology, “Fixed Transects for Determining the Minimum Number of Distinct Individuals” is not easy. In our most parrot populous area there were nearly 1200 Pacific parakeets, and over 700 hundred yellow-naped and red-lored parrots. For each parrot we had to ask, “Whose are they? Who left us? Who came to us? Did we honor what we saw? Did we check our assumptions, observations, and math with others?” Our questions were like a congregated spiritual discovery, where we produced a holy result where every individual person and parrot mattered, and was worthy of our focus and attention. The maps we drew showed not just our location, but every flight represented by an arrow. These flight paths intersected in and out like a spider’s web or threads on a loom. In making these maps, we wove together the rends in the web of life caused by human exceptionalism and our false sense of separation. Instead we wove our species in among the worthy others. It took hours on the final day to summarize all the days, first by individual sheets, and then each region, and then all the 4 regions together. One region met until nearly midnight to tabulate their results, and another was still going on Sunday morning (Teams La Peña, Totoca, La Palma, and Merida below summarizing)

It took hours on the final day to summarize all the days, first by individual sheets, and then each region, and then all the 4 regions together. One region met until nearly midnight to tabulate their results, and another was still going on Sunday morning (Teams La Peña, Totoca, La Palma, and Merida below summarizing)

After finishing our last summary, I remarked that I didn’t want to see another number again for at least a week, and was met with wearied smiles as I looked around at the counters. But not even 12 hours later, I was contacted by one counter who said he was going out that very evening to try to figure out in more detail the flight, foraging, and roosting patterns of his community birds. He was going beyond, and he told me it was because of love. He wasn’t alone. Everyone had gone beyond expectations to focus and to honor every single parrot in their location. Such careful observation to claim the birds counted in our locations, led us to being claimed by the birds.

After finishing our last summary, I remarked that I didn’t want to see another number again for at least a week, and was met with wearied smiles as I looked around at the counters. But not even 12 hours later, I was contacted by one counter who said he was going out that very evening to try to figure out in more detail the flight, foraging, and roosting patterns of his community birds. He was going beyond, and he told me it was because of love. He wasn’t alone. Everyone had gone beyond expectations to focus and to honor every single parrot in their location. Such careful observation to claim the birds counted in our locations, led us to being claimed by the birds. The parrots help our hearts soar.I witnessed commitment, purpose, and expertise in this group of conservationists who will make a better future possible for the people and parrots of this island. Life has not been easy for the parrots due to poaching fueled by the international parrot trade, or for the people slammed from the economic fallout from the civil unrest in the last year. One counter said he almost left Nicaragua last year to attempt the perilous journey north to the USA, so desperate was he for paid work. But at least for this one week, families benefited from the stipends and meals offered during the long days, and now with greater capacity, are ready to be ecotourist and scientific guides for those who wish to observe and study these birds. Maybe they can elect to stay and not migrate if there are opportunities for them here, and also an increased connection to the life they study, count, and treasure. As they grow their capacity as conservationists, I hope that they will gain greater confidence to find a way forward of greater well-being, for all.

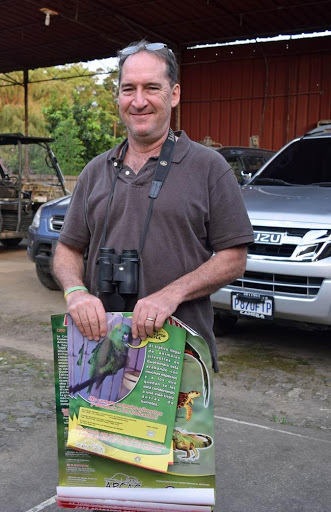

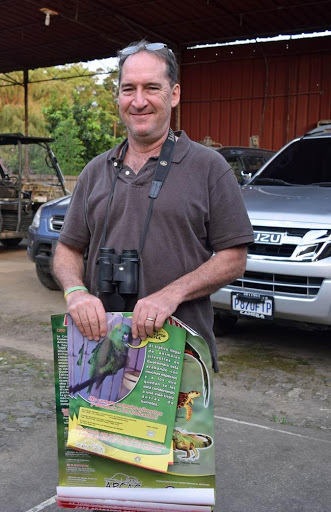

The parrots help our hearts soar.I witnessed commitment, purpose, and expertise in this group of conservationists who will make a better future possible for the people and parrots of this island. Life has not been easy for the parrots due to poaching fueled by the international parrot trade, or for the people slammed from the economic fallout from the civil unrest in the last year. One counter said he almost left Nicaragua last year to attempt the perilous journey north to the USA, so desperate was he for paid work. But at least for this one week, families benefited from the stipends and meals offered during the long days, and now with greater capacity, are ready to be ecotourist and scientific guides for those who wish to observe and study these birds. Maybe they can elect to stay and not migrate if there are opportunities for them here, and also an increased connection to the life they study, count, and treasure. As they grow their capacity as conservationists, I hope that they will gain greater confidence to find a way forward of greater well-being, for all. Our leader, Norlan Zambrana Morales marking a point of a roost siteThe lead parrot conservationist told me on the last day, “This parrot project has benefited so many people on this island.” I teared up, knowing that perhaps it was me who had benefited the most, for I was forged into a group of 20 who had done sacred work for a sacred cause – the flourishing of people and parrots of the Americas.I left the island a little less lonely and a little better at math.

Our leader, Norlan Zambrana Morales marking a point of a roost siteThe lead parrot conservationist told me on the last day, “This parrot project has benefited so many people on this island.” I teared up, knowing that perhaps it was me who had benefited the most, for I was forged into a group of 20 who had done sacred work for a sacred cause – the flourishing of people and parrots of the Americas.I left the island a little less lonely and a little better at math.

Published on July 25, 2019 10:59

July 16, 2019

Biodiversity Loss and the Climate Crisis

LoraKim is now in Nicaragua for a week, working with our partners on Ometepe Island to assist the endangered yellow-naped amazon and other parrot species that live there. So, it’s my turn again to write this week’s blog.In addition to my work as Co-Director of One Earth Conservation, I am also a long-time environmental and climate activist. For as long as I can remember, I’ve been spending whatever time I can spare working, first, to assist endangered species and then, later, to alert as many people as possible to the dire effects of climate change that could be, and now to some extent are, upon us. In 2013 I trained with the Climate Reality Project to learn about and educate others about the climate crisis, why it is happening, why it matters and what each of us might do to avert the worst possible scenario. Despite many unfortunate setbacks, there have also been some recent gains, such as passage of New York State’s Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act.In parallel to my climate-related concerns, I have become increasingly alarmed about the major loss of biodiversity that is now occurring. In my blog on May 8, 2019, I discussed the Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services issued by the UN group, the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES). The first sentence of the press release regarding this report says it all:“Nature is declining globally at rates unprecedented in human history — and the rate of species extinctions is accelerating, with grave impacts on people around the world now likely, warns a landmark new report …”

LoraKim is now in Nicaragua for a week, working with our partners on Ometepe Island to assist the endangered yellow-naped amazon and other parrot species that live there. So, it’s my turn again to write this week’s blog.In addition to my work as Co-Director of One Earth Conservation, I am also a long-time environmental and climate activist. For as long as I can remember, I’ve been spending whatever time I can spare working, first, to assist endangered species and then, later, to alert as many people as possible to the dire effects of climate change that could be, and now to some extent are, upon us. In 2013 I trained with the Climate Reality Project to learn about and educate others about the climate crisis, why it is happening, why it matters and what each of us might do to avert the worst possible scenario. Despite many unfortunate setbacks, there have also been some recent gains, such as passage of New York State’s Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act.In parallel to my climate-related concerns, I have become increasingly alarmed about the major loss of biodiversity that is now occurring. In my blog on May 8, 2019, I discussed the Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services issued by the UN group, the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES). The first sentence of the press release regarding this report says it all:“Nature is declining globally at rates unprecedented in human history — and the rate of species extinctions is accelerating, with grave impacts on people around the world now likely, warns a landmark new report …” (Photo from IPBES website) I find myself increasingly focused on the intersection of my work with One Earth Conservation on biodiversity loss, specifically among Latin American parrots, and my work as a climate activist. I see the intersection of these two huge issues everywhere – for example, poachers in Central America cut down trees to reach parrot chicks, which causes both parrot populations and the number of trees to decline. Those activities in turn accelerate both biodiversity loss and the climate crisis.The IPBES report’s press release also includes this statement from IPBES Chair, Sir Robert Watson, ““The member States of IPBES Plenary have now acknowledged that, by its very nature, transformative change can expect opposition from those with interests vested in the status quo, but also that such opposition can be overcome for the broader public good,” So, we all must keep our eyes on the two balls of biodiversity loss and climate change. If we admit what is happening, each do our part and don’t ever give up, together we can reach a tipping point that will make a difference.If you are in the New York metropolitan area and would like to learn more about this issue, please click here to learn more about a free panel discussion hosted by the Climate Reality Project NYC Metro Chapter on Tuesday evening, July 23, 2019 about biodiversity loss and climate change on which I will be participating.

(Photo from IPBES website) I find myself increasingly focused on the intersection of my work with One Earth Conservation on biodiversity loss, specifically among Latin American parrots, and my work as a climate activist. I see the intersection of these two huge issues everywhere – for example, poachers in Central America cut down trees to reach parrot chicks, which causes both parrot populations and the number of trees to decline. Those activities in turn accelerate both biodiversity loss and the climate crisis.The IPBES report’s press release also includes this statement from IPBES Chair, Sir Robert Watson, ““The member States of IPBES Plenary have now acknowledged that, by its very nature, transformative change can expect opposition from those with interests vested in the status quo, but also that such opposition can be overcome for the broader public good,” So, we all must keep our eyes on the two balls of biodiversity loss and climate change. If we admit what is happening, each do our part and don’t ever give up, together we can reach a tipping point that will make a difference.If you are in the New York metropolitan area and would like to learn more about this issue, please click here to learn more about a free panel discussion hosted by the Climate Reality Project NYC Metro Chapter on Tuesday evening, July 23, 2019 about biodiversity loss and climate change on which I will be participating.

Published on July 16, 2019 08:31

July 9, 2019

Trashed Oceans and Plasticity

Usually when I talk about being plastic in conservation I mean that we grow our emotional and social intelligence so that we can learn and adapt to others and a changing world. We grow because we want happier and more meaningful lives, and also because we are better conservationists and community members when we train our minds to “go with the flow” in complex social situations. We are adaptable and resilient, while not letting go of expressing, honestly and empathetically the harm done by others to ourselves and life. I recently learned a whole meaning of going with the flow and being plastic. I worked on the Atlantic Coast of Guatemala in June 2019 surveying the endangered yellow-headed parrot with our partners (CONAP,FUNDAECO, and the village of Quineles). We had to camp on the beach, which was covered in plastic refuse. Everywhere I walked I heard the crunch, crunch of plastic beneath my feet, and when I was in the waves walking around mangrove trees, the bits of plastic swirled and caught on my legs. I was repulsed by the syringes, toothbrushes, flip-flops, bottles, etc everywhere I looked.

I recently learned a whole meaning of going with the flow and being plastic. I worked on the Atlantic Coast of Guatemala in June 2019 surveying the endangered yellow-headed parrot with our partners (CONAP,FUNDAECO, and the village of Quineles). We had to camp on the beach, which was covered in plastic refuse. Everywhere I walked I heard the crunch, crunch of plastic beneath my feet, and when I was in the waves walking around mangrove trees, the bits of plastic swirled and caught on my legs. I was repulsed by the syringes, toothbrushes, flip-flops, bottles, etc everywhere I looked. And this amount of plastic was just what I could see. Microplastics are throughout the oceans, resulting in 100% of sea turtles and 60% of seabirds having plastic in their bodies. Humans too ingest these potentially harmful substances, becoming plastic altogether in a very different way.The plastic on this particular stretch of beach comes from the Motagua River, which is trashing beaches and islands in the entire region. The Motagua River flows from Guatemala’s interior where town after town throws its garbage into the river. There is so much thrown off plastic-ware, that each of us in a minute or two could find a pair of crocs or flip flops to match our shoe size. The colors or styles didn’t always match, so we had a few laughs as we worked around the flow of plastic that came from afar and would stay a long time on this beach. We had to find humor because we were living in a trashed environment, with shockingly fewer parrots than the last time we counted here and fewer mangrove trees, many that were stunted or leaning in dying groves.

And this amount of plastic was just what I could see. Microplastics are throughout the oceans, resulting in 100% of sea turtles and 60% of seabirds having plastic in their bodies. Humans too ingest these potentially harmful substances, becoming plastic altogether in a very different way.The plastic on this particular stretch of beach comes from the Motagua River, which is trashing beaches and islands in the entire region. The Motagua River flows from Guatemala’s interior where town after town throws its garbage into the river. There is so much thrown off plastic-ware, that each of us in a minute or two could find a pair of crocs or flip flops to match our shoe size. The colors or styles didn’t always match, so we had a few laughs as we worked around the flow of plastic that came from afar and would stay a long time on this beach. We had to find humor because we were living in a trashed environment, with shockingly fewer parrots than the last time we counted here and fewer mangrove trees, many that were stunted or leaning in dying groves. My camping hammock with shoes waiting to slip into, and these were shoes I didn't pack with meI vowed on that beach to no go with the flow. I have to change my consumer choices that involve plastic. It’s not acceptable that we use so much plastic and dispose of it inadequately. It’s not acceptable that beauty is thwarted and life harmed. We must find a way to use less plastic and help others to dispose of it properly. Simply blaming communities is not the answer, though there is plenty of that bouncing back and forth between Guatemala and Honduras. People need solutions, and their communities need the world to know of the challenges in their social structures and economies that make it difficult to handle garbage any differently than they do.

My camping hammock with shoes waiting to slip into, and these were shoes I didn't pack with meI vowed on that beach to no go with the flow. I have to change my consumer choices that involve plastic. It’s not acceptable that we use so much plastic and dispose of it inadequately. It’s not acceptable that beauty is thwarted and life harmed. We must find a way to use less plastic and help others to dispose of it properly. Simply blaming communities is not the answer, though there is plenty of that bouncing back and forth between Guatemala and Honduras. People need solutions, and their communities need the world to know of the challenges in their social structures and economies that make it difficult to handle garbage any differently than they do. So many people have been “sold a bill of goods,” in this case plastic-wrapped or plastic-bagged this or that, while their interests and needs have been “thrown away,” treated as garbage. The beach screamed injustice, and I inwardly screamed back. Though my reaction was strongly that of disgust on this beach, I also felt a connection to humanity, because it was profoundly intimate to walk a mile in other people’s shoes, and see what was discarded from their homes.

So many people have been “sold a bill of goods,” in this case plastic-wrapped or plastic-bagged this or that, while their interests and needs have been “thrown away,” treated as garbage. The beach screamed injustice, and I inwardly screamed back. Though my reaction was strongly that of disgust on this beach, I also felt a connection to humanity, because it was profoundly intimate to walk a mile in other people’s shoes, and see what was discarded from their homes. Hard to know where our camp ends and the trash heap beginsMay we wake up to each other’s trash and humanity, and change our course.Each can engage in a beach cleanup, though clean ups are just removing a tiny bit of the 8 million metric tons of plastic dumped in the oceans each year, and their impact is debatable. We also need to hold plastic companies accountable and insist they develop alternative products that decompose naturally. And each of us who can, need to not just reduce the plastic we consume, but all that we consume…For each other, for the beaches, for beauty, for the trees, for the parrots, and for all that is life.

Hard to know where our camp ends and the trash heap beginsMay we wake up to each other’s trash and humanity, and change our course.Each can engage in a beach cleanup, though clean ups are just removing a tiny bit of the 8 million metric tons of plastic dumped in the oceans each year, and their impact is debatable. We also need to hold plastic companies accountable and insist they develop alternative products that decompose naturally. And each of us who can, need to not just reduce the plastic we consume, but all that we consume…For each other, for the beaches, for beauty, for the trees, for the parrots, and for all that is life.

I recently learned a whole meaning of going with the flow and being plastic. I worked on the Atlantic Coast of Guatemala in June 2019 surveying the endangered yellow-headed parrot with our partners (CONAP,FUNDAECO, and the village of Quineles). We had to camp on the beach, which was covered in plastic refuse. Everywhere I walked I heard the crunch, crunch of plastic beneath my feet, and when I was in the waves walking around mangrove trees, the bits of plastic swirled and caught on my legs. I was repulsed by the syringes, toothbrushes, flip-flops, bottles, etc everywhere I looked.

I recently learned a whole meaning of going with the flow and being plastic. I worked on the Atlantic Coast of Guatemala in June 2019 surveying the endangered yellow-headed parrot with our partners (CONAP,FUNDAECO, and the village of Quineles). We had to camp on the beach, which was covered in plastic refuse. Everywhere I walked I heard the crunch, crunch of plastic beneath my feet, and when I was in the waves walking around mangrove trees, the bits of plastic swirled and caught on my legs. I was repulsed by the syringes, toothbrushes, flip-flops, bottles, etc everywhere I looked. And this amount of plastic was just what I could see. Microplastics are throughout the oceans, resulting in 100% of sea turtles and 60% of seabirds having plastic in their bodies. Humans too ingest these potentially harmful substances, becoming plastic altogether in a very different way.The plastic on this particular stretch of beach comes from the Motagua River, which is trashing beaches and islands in the entire region. The Motagua River flows from Guatemala’s interior where town after town throws its garbage into the river. There is so much thrown off plastic-ware, that each of us in a minute or two could find a pair of crocs or flip flops to match our shoe size. The colors or styles didn’t always match, so we had a few laughs as we worked around the flow of plastic that came from afar and would stay a long time on this beach. We had to find humor because we were living in a trashed environment, with shockingly fewer parrots than the last time we counted here and fewer mangrove trees, many that were stunted or leaning in dying groves.

And this amount of plastic was just what I could see. Microplastics are throughout the oceans, resulting in 100% of sea turtles and 60% of seabirds having plastic in their bodies. Humans too ingest these potentially harmful substances, becoming plastic altogether in a very different way.The plastic on this particular stretch of beach comes from the Motagua River, which is trashing beaches and islands in the entire region. The Motagua River flows from Guatemala’s interior where town after town throws its garbage into the river. There is so much thrown off plastic-ware, that each of us in a minute or two could find a pair of crocs or flip flops to match our shoe size. The colors or styles didn’t always match, so we had a few laughs as we worked around the flow of plastic that came from afar and would stay a long time on this beach. We had to find humor because we were living in a trashed environment, with shockingly fewer parrots than the last time we counted here and fewer mangrove trees, many that were stunted or leaning in dying groves. My camping hammock with shoes waiting to slip into, and these were shoes I didn't pack with meI vowed on that beach to no go with the flow. I have to change my consumer choices that involve plastic. It’s not acceptable that we use so much plastic and dispose of it inadequately. It’s not acceptable that beauty is thwarted and life harmed. We must find a way to use less plastic and help others to dispose of it properly. Simply blaming communities is not the answer, though there is plenty of that bouncing back and forth between Guatemala and Honduras. People need solutions, and their communities need the world to know of the challenges in their social structures and economies that make it difficult to handle garbage any differently than they do.

My camping hammock with shoes waiting to slip into, and these were shoes I didn't pack with meI vowed on that beach to no go with the flow. I have to change my consumer choices that involve plastic. It’s not acceptable that we use so much plastic and dispose of it inadequately. It’s not acceptable that beauty is thwarted and life harmed. We must find a way to use less plastic and help others to dispose of it properly. Simply blaming communities is not the answer, though there is plenty of that bouncing back and forth between Guatemala and Honduras. People need solutions, and their communities need the world to know of the challenges in their social structures and economies that make it difficult to handle garbage any differently than they do. So many people have been “sold a bill of goods,” in this case plastic-wrapped or plastic-bagged this or that, while their interests and needs have been “thrown away,” treated as garbage. The beach screamed injustice, and I inwardly screamed back. Though my reaction was strongly that of disgust on this beach, I also felt a connection to humanity, because it was profoundly intimate to walk a mile in other people’s shoes, and see what was discarded from their homes.

So many people have been “sold a bill of goods,” in this case plastic-wrapped or plastic-bagged this or that, while their interests and needs have been “thrown away,” treated as garbage. The beach screamed injustice, and I inwardly screamed back. Though my reaction was strongly that of disgust on this beach, I also felt a connection to humanity, because it was profoundly intimate to walk a mile in other people’s shoes, and see what was discarded from their homes. Hard to know where our camp ends and the trash heap beginsMay we wake up to each other’s trash and humanity, and change our course.Each can engage in a beach cleanup, though clean ups are just removing a tiny bit of the 8 million metric tons of plastic dumped in the oceans each year, and their impact is debatable. We also need to hold plastic companies accountable and insist they develop alternative products that decompose naturally. And each of us who can, need to not just reduce the plastic we consume, but all that we consume…For each other, for the beaches, for beauty, for the trees, for the parrots, and for all that is life.

Hard to know where our camp ends and the trash heap beginsMay we wake up to each other’s trash and humanity, and change our course.Each can engage in a beach cleanup, though clean ups are just removing a tiny bit of the 8 million metric tons of plastic dumped in the oceans each year, and their impact is debatable. We also need to hold plastic companies accountable and insist they develop alternative products that decompose naturally. And each of us who can, need to not just reduce the plastic we consume, but all that we consume…For each other, for the beaches, for beauty, for the trees, for the parrots, and for all that is life.

Published on July 09, 2019 11:49

July 2, 2019

Going Forth in Conservation

Our conservation group in Punta Manabique along the Atlantic Coast of Guatemala - flying free as our spirits soar together for the sake of the yellow-headed parrots (Noe, Jesus, LoraKim, Julian, Yaqui, Roxana, Miguel, Miguel, Erick)Recently while working with the endangered yellow-headed parrot in Guatemala, where there are less than 100 individuals, I had a conversation with one of CONAP’s staff members.

Our conservation group in Punta Manabique along the Atlantic Coast of Guatemala - flying free as our spirits soar together for the sake of the yellow-headed parrots (Noe, Jesus, LoraKim, Julian, Yaqui, Roxana, Miguel, Miguel, Erick)Recently while working with the endangered yellow-headed parrot in Guatemala, where there are less than 100 individuals, I had a conversation with one of CONAP’s staff members. CONAP colleagues Miguel, Salvador, Julian, and Noe at our beach campHe asked me about my work as a Unitarian Universalist minister and I said that I didn’t serve congregations so much anymore, but that my ministry was concrete conservation work with communities in the Americas. He replied, “Well that makes sense, for after all Jesus told us to go forth into the world.” I don’t know if I am following the guidance of any one religion with my conservation work, but I do have a sense of urgency that the earth needs our deep commitment and rapid action, now.