E.C. Fuller's Blog

January 3, 2025

2024 Year in Review

Now, at the end of another journey around the sun, it’s time to look at the data and validate my feelings.

This is my 2024 Year in Review! The seventh data-backed story of my year.

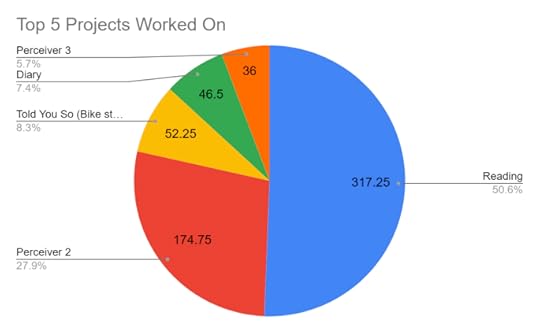

The DataI wrote, read, and revised a total of 831 hours rounded down. This is the least amount of hours I’ve worked per year since I’ve started tracking. It’s also 141 hours less than last year, and almost half my highest total. Yeesh.

As usual, reading took the top spot. I read slightly less than usual, but still about as much as I normally do per year. Perceiver 2 takes second place, and the sequel, Perceiver 3, takes fifth. “Told You So” is a short story that I’ve spent far too long on. Diary is, of course, my diary.

Why is my total number of hours lower than ever? I think it’s because my writing resolutions conflicted with my other resolutions for exercise. I weight lift and cycle, and in 2024, I had strength and speed goals that I was trying to reach. My Apple health app reported that I had increased the time per day that I work out. Factoring in travel to the gym and to my bike club, it matches the chunk of time missing from this year.

Wasn’t 2024 going to be the year I bounced back? Well, I sort of did.

2023 ResolutionsBring my current WIP short stories and novella to submission-ready status. Concrete goal: 1.0 hours/day of revision, submission, workshopping, etc, until all of them are out on submission. Yes! I actually exceeded this goal. Two short stories were accepted for publication, one to be published early in 2025, and the novella and two short stories are out on submission.Continue TikTok series: Concrete goal: at least two TikTok posts per week, goal of 100 posts by the end of the year. Nope. I made around 40 posts. When the news broke that TikTok would be banned, it killed a lot of my momentum to keep working on that platform. I want to bring the sequel to my second book to publication-ready status. Nope. But I made a massive amount of progress. I reckon I’m 70-75% of the way through.Three pages every day. Yes! 13 years strong!2024 ResolutionsFinish the current draft of Perceiver 2 and send it to beta readers. Concrete goal: Work on it every day until it’s sent off.Finish another draft of P3. I didn’t get very far writing the third book in 2024. The second book has changed so much that it feels premature to write in such detail. Concrete goal: once P2 is off to beta-readers, work on P3 every day.Try to write, read, or revise at least 2.75 hours per day. I want to make a yearly goal to work on writing at least 1,000 hours per year, which breaks down to about 2.75 hours per day.An anecdote of significanceSomeone online said it’s scientifically impossible to be sad while riding a bike. I said, Oh really? and got into bikepacking. Backpacking is where you head out into the wilderness carrying everything you need on your person: food, shelter, toiletries, and so on, but on a bike.

My thinking was that I could get fit, save on gas, get some social time, and do some cool camping and touring activities while researching for my stories. I’d started a series of short stories focused on Tulsa in the year 2050, after a climate disaster known as the Summer of Storms ravaged infrastructure, crops, and the grid across the world. I imagined that bikes would be critical to survival—not just for daily life, such as commuting or errands, but for key services like delivery, communication, and even escaping from dangerous areas. One of the stories, “Soft Serve”, had already been published (go here to read the story, here to read my notes for it).

I joined a local bike club’s Monday Funday rides. We meet at the bike shop to ride to a new restaurant each week, about five miles away. No one gets left behind.

Or so I thought.

My very first ride was on a day with a heat advisory. One of those flat, blue-sky days where the sun beats down, the road feels like a griddle, and you’re in the middle of it, mashing the pedals. I was the slowest by far, riding a bike that wasn’t suited for the task. Before we headed out, one of the regulars asked me what kind of bike I was riding. I said, “Extra small.” I later learned it was a fitness bike, also known as a commuter or hybrid bike. Most of the regulars had road bikes and wore the tight lycra bike outfits and the little shoes that clip into the pedals.

I was chatting with one of them as we headed out. I was trying hard to stay next to him to keep talking, but he wasn’t trying hard at all. He had the air of someone out on a Sunday stroll.

I thought I was doing okay, but then we hit a hill. A small hill. A hill I’d walked and run and cycled up a hundred times before. But that day, I had already ridden 5 miles at an rpm far higher than my usual syrupy-slow spin. My breathing was ragged when we started. Halfway up, my vision started dimming around the sides. At the top of the hill, my breath wouldn’t catch. When I called for a break, my heart was hammering. Dumping my water bottle over my head didn’t help, and we were only halfway to the restaurant.

I felt embarrassed that people had to stop for me. I had been weight lifting and running for a year and a half, and I considered myself in good shape. I didn’t understand why I was having such a hard time keeping up with the regulars. Yet the break stretched on, and I failed to catch my breath. At last one of them mentioned when they would start again. I knew then that I would probably pass out if I tried to finish the ride with them.

I considered dropping out and going home. The group had just passed my lushly air conditioned apartment. My confidence had been pantsed. At that point, I didn’t like cycling that much, and I was worried it would become yet another expensive hobby doomed to be abandoned after a year.

But instead, I took a ride in the support vehicle, and I met up with the group for dinner at a greasy spoon. Part of why I stayed was stubbornness. I don’t like being humiliated, but I’ll deal with it if it means finishing something to my satisfaction. I was likely the only one embarrassed by my lack of stamina and speed. I wanted to make sure that embarrassment was temporary, and I knew if I went home I would never return.

And I did return, again and again, every Monday. Several months passed. I’d practiced hard and completed my first bikepacking trip: a 60-mile round trip from Tulsa to Keystone Dam. It was paved road-only, not too many hills. 30 miles per day. Difficult but achievable for a new bikepacker.

But the second trip started with an 85-mile leg that was mostly on gravel. The second day was 50 miles, half on gravel. I doubted I could make it, but I was determined to try.

The first 10 miles were smooth and paved. I screwed up on velcroing my dry bags to my bike rack and had to stop to reattach them securely, and so did someone else. Then, I got a flat, and the main group got lost and turned around on the backroads. We had a few uneventful miles.

It all went to shit on gravel. Gravel is loose. Your bike skids and judders underneath you, like riding a jackhammer. Uphill, already the opposite of the bee’s knees, is worse because your tires spin and slip. Downhill, you’re too worried about skidding off to enjoy the ride.

Starting around noon, the wind picked up and whipped gravel dust into our eyes, nose, and mouth. One sip from my water bottle gave me twice my daily minerals and probably other minerals I shouldn’t have eaten. As the sun traveled on, the wind turned into a 20 mph headwind. The literal air was against us. We rode like this for hours.

I was thinking insane shit trying to keep my legs spinning. I sung the first lyrics to the Marine’s Hymn. “From the halls of Montezuma to the shores of Tripoli, we will fight for right and freedom, and to keep our honor free….” I couldn’t remember further than that so I just sung those lines over and over. When looking for the link to the song lyrics, I discovered barely anything I sung were the correct lyrics. I thought of Sisyphus. Sisyphus was an asshole who deserved his boulder, but what did I do? I thought of a haiku:

If this wind doesn’t

goddamn stop blowing on me

so help me god

It’s one syllable short but it captured my feelings. On trips this long, there’s nothing for your mind to do but spin in its cage of bone and chatter. I cajoled my legs to keep working at all costs. I was already in the back of the pack, and I fell behind even further. I didn’t have the trip map or a GPS, and I wasn’t close enough to the main group to be able to see and follow them, so one of the trip leaders stuck with me so I wouldn’t get lost. I was being babysat, and I didn’t want to hold him back. I didn’t want to stop riding, and yet, I couldn’t keep going. I was wrung out, close to bonking.

After 37 miles, I tapped out and caught a ride in the support truck. The guy who had stuck with me took off like a shot, and I thought, be free, my dude. I tried to reason with myself in the truck. It sucked that you weren’t able to finish, but you got further than you thought you would. Tomorrow was a shorter ride. Why not chill out, rest, refuel, and try again tomorrow?

Upon checking my phone, I found that I got a rejection from a literary magazine, which had also delivered a stinging critique of the submitted story. I had paid extra for editorial feedback, so I expected something. Still. It felt like being kicked when I was down.

The critique of the story also came at a moment when I felt like I was losing steam as a writer. My writing group of five years had broken up right before the trip. It had been on the rocks for a while, and it seemed like I was the only one regularly submitting work for critique for months.

I had hit rough patches for revising Perceiver 2 and 3, and I had no responses from magazines about my other short story submissions.

Writing has always been a very inward-facing activity, usually practiced by the introspective—who, paradoxically, succeed when their writing connects with others. Writing primes you to love bikepacking. Both are endurance activities. Both activities are described as journeys. Both are what you might call “Type 2 fun.”*

*(Type 1 fun is fun in the moment. Type 2 fun is only fun in hindsight. See the Fun Scale.)

What do I see in embarking on these journeys? Why do I pick up a boulder and go up and down hills? My answer is in this relevant Buddhist parable, as related by Pema Chodron:

“There is a story of a woman running away from tigers. She runs and runs and the tigers are getting closer and closer. When she comes to the edge of a cliff, she sees some vines there, so she climbs down and holds on to the vines. Looking down, she sees that there are tigers below her as well. She then notices that a mouse is gnawing away at the vine to which she is clinging. She also sees a beautiful little bunch of strawberries close to her, growing out of a clump of grass. She looks up and she looks down. She looks at the mouse. Then she just takes a strawberry, puts it in her mouth, and enjoys it thoroughly.” ― Pema Chödrön, The Wisdom of No Escape: How to Love Yourself and Your World

During the second trip, I remember looking up after fighting to keep up, sweat stinging my eyes, and seeing autumn leaves against a blue sky. Clouds scattered above a gravel road stretched out before me, everyone grinding up the hill, calling and laughing to each other. I was dead last, not even 10 miles into the trip, but I was alive. That was one strawberry among many on the trip. Baby goats in a yard. The people who sit around the campfire with me. The delicious lemonade and BBQ smoked meat from some random truck parked across a gas station! (Why is the best food always from the sketchiest places?)

My strawberries in writing are a phrase that perfectly captures what I’m trying to say. Or I think of a scene that surprises me but fits perfectly. Or I finally reach that point where the story has a current that catches the protagonists and carries them inexorably to their transformative end.

It feels precious and cringe-worthy to delight in these things. But happiness—real happiness—often feels embarrassing to admit when the world is so heavy with pain. It feels easier to admit failure or rage because these reactions seem more justified, more expected. It is worse, somehow, to admit the strawberries foraged from daily writing are also not enough to sustain me, when American culture is so adamant that practicing your art should be enough to do it for you. To need is mortifying.

I need magazines to get back to me. I need people to stop using Chat GPT to write their stories for them, so magazines would have shorter response times and get back to me sooner. I need TikTok to not get banned, so I can keep using the one platform that I’m good at. I need a giant hand to reach down, sweep away the gravel, change the direction of the wind to be at my back, and pluck me up and set me on top of a hill, so I can ride down.

What I have—is a great group of people to ride with. They arranged the campgrounds and mapped out the rides. They encouraged me and gave me advice. They introduced me to great local eats. They also hung back to make sure I didn’t get lost. I got to camp that day thanks to the drivers of the support vehicle. When I started, I merely liked cycling. But it is their enthusiasm that has moved cycling next to my heart, just behind writing.

The following day, I tried to ride with the group, and stayed close enough to glimpse the second-to-last person appearing and disappearing around the hills. I quit at 30 miles. I was simply not conditioned enough to keep going. Thus, I spent the drive home thinking about how to train for the next trip.

I wish I could give you some parable about perseverance in the face of silence and apathy. For bikepacking and cycling, it’s the people. On the other hand, writing is a habit I don’t know how to quit. The merest encouragement sustains me for months. Ex., shortly after the trip, I received a notice from a magazine that my story had made it to the final round. The accompanying editorial comments were so nice I danced around my apartment like a nut. That story was eventually accepted, and it will be published in early 2025.

What have I learned in 2024? Perhaps that objects of desire lie just beyond the grasp of reason, but are within reach if you keep going? No, it is the same lesson I learn every year: that I like writing, and that I’m going to keep doing it, uphill, downhill, against the wind, or not.

Still: I will be looking for a new writer’s group in 2025.

The post 2024 Year in Review appeared first on EC Fuller's Books.

August 20, 2024

Story Inspiration: Soft Serve

My short story, “Soft Serve”, has been accepted by State of Matter and is in the August 2024 issue! You can read the story here.

InspirationWhen I was in middle school, my history teacher said that empires rise and fall on a 300-year cycle. I could do math at the time, and I realized that I would be around during the presumptive fall of the American empire. I follow the news on climate change and our increasingly short timeline for correcting our ways, plus the wars waged around the world and civil unrest in America, and the neglect of physical and societal infrastructure. I began to wonder if we’re already falling and what life will be like twenty-five years from now.

This wondering took the shape of writing short stories based on Tulsa, OK in 2050. Some of them are more hopeful than others. Some of them are extreme versions of what I have seen played out in Oklahoma. The first of them is one such extreme: “Soft Serve”.

“Soft Serve” is based on a visit to the doctor. I was in the waiting room with about 10 other people, waiting to get my blood drawn. It’s just one of those unpleasant necessities, but we’re all stoic about it.

But at least one person in the waiting room didn’t know what was about to happen. There was a little girl drawing with markers on a coloring book on the floor. She’s singing a little. A woman I presume is her mom is watching her drawing. A name gets called. The mom and girl go through the door. It shuts behind them. Then the little girl starts screaming. Two female voices soothe her, but it’s going on for a really long time. People shift in their chairs, catch each others’ eyes, and do a weird half-smile. And the little girl just keeps screaming. I start to think, you know, maybe something terrible is happening back there. Maybe she’s screaming for good reason. Maybe I should get up and do something.

Eventually the little girl comes out with her mom. There’s a bandage on her arm and tears in her eyes, and her mom leads her quickly out the door.

I couldn’t stop thinking about her screaming and that what-if. All around the world, there are practices that people think are unpleasant necessities, but in reality are brutal non-essentials. What-if there was something more sinister happening behind that door? What-if what I’m seeing in Oklahoma has warped normality? What-if we’ve already decided to not open the door?

You can read “Soft Serve” here.

The post Story Inspiration: Soft Serve appeared first on EC Fuller's Books.

March 6, 2024

2023 Year in Review

You're currently a free subscriber. Upgrade your subscription to get access to the rest of this post and other paid-subscriber only content.

Upgrade subscriptionThe post 2023 Year in Review appeared first on EC Fuller's Books.

January 3, 2023

2022 Year in Review

If you’re sick of yearly round ups from people who’ve written a million words, climbed Mt. Fuji using only their hands, and developed rippling abs, you’ve come to the right place. I set many resolutions last year and kept only one of them.

But many wonderful things happened this year that I never expected. I wanted to share the numbers and explain how they don’t express the larger message: that I’m getting close to writing the kinds of stories I’ve always wanted to write, and the life to support my writing.

This is the fifth data-backed story of my year.

For previous reviews, here is a list of links:

Methodology“I am always chagrined at the tendency of people to expect that I have a simple, easy gimmick that makes my program function. Any successful program functions as an integrated whole of many factors. Trying to select one aspect as the key one will not work. Each element depends on all the others.”

Admiral James Rickover, father of the modern nuclear navy

This quote has guided my ethos in staying productive and on track to achieving my writing goals: to write a story that someone will devour, at the end, sigh, “wow,” and feel both full and cored out; and, when reread, will find something new. I want to write something that means as much to readers as my favorites did to me. To achieve that lofty goal, I created a writing system to generate a virtuous cycle of continuous improvement.

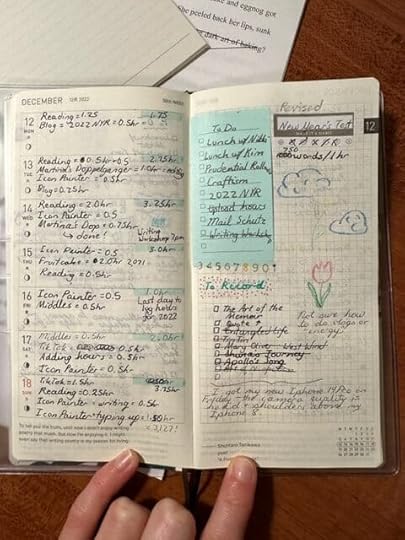

I track time by project* and task. Using pomodoro apps like this one or this one, the timer on my computer, or even glancing at the clock, I note when I start and stop. Time spent is rounded up to the nearest fifteen minutes. I first record longhand using a weekly planner, with notes on where I worked, special events, appointments, and other activities. Then, weekly or monthly, I upload the numbers into an app called atWork. At the end of the year, I download the data, clean it, and analyze it using Google Sheets.

Example of time tracking in Hobonichi Weeks

Example of time tracking in Hobonichi WeeksFor example, a typical day’s time entry might look like this:

Perceiver 2, 1.0 hours, editing

Reading, 1.0 hour

TikTok, 0.75 hour, scripting

This is the perfect amount of detail for me. Tracking by time isn’t as strict as a word count, which isn’t always the best measure of progress on a project. Though, I’ll track word count for new stories just to keep myself at a steady completion rate. If a certain task is taking up too much time, I can look it over to see where I can improve the process. For example, one year I discovered that typing up my notebooks took over 80 hours to complete. So… I switched the three pages to my diary and tried to write solely on the computer.

But. It didn’t work. Because I’m almost always staring at a screen for work, and then TikTok, after a certain point my eyes felt like they’re drying up and rolling out of my skull. Instead of writing more fiction on the computer, I just wrote in my tiny diary and called that writing. Paradoxically, by trying to work more efficiently, I ended up working less.

There’s something about writing that first draft longhand that just works for me. Printing and editing my work by hand helps too. But, I rewrote much of Perceiver 2 bypassing my notebook entirely. Maybe there’s still hope for me? I’ll circle back to this later.

For projects like TikTok (or in general, Social Media Management), I only time track when I’m working deliberately, such as scripting, recording, editing, posting, or responding to questions and comments. If I’m mindlessly scrolling, it doesn’t count as work. Same for research. For example, I watched a documentary about fungi for a short story. I kept pausing the documentary to take down the names of interviewed researchers and to take notes. But soon after, I watched another documentary about deep sea gigantism. The time I spent watching the second documentary wasn’t tracked, because I didn’t do it for anything I was writing.

*2022 is my first full year tracking my time by project rather than task.

By the numbersClearly the trend is going down. But, three of the last five logged years have been a pandemic. The big drop in 2020 is my first full year working a full-time job. My goal isn’t always to work more—it’s to work more efficiently. My heart sinks when I think of what I could have done… but it lifts knowing how much I accomplished during the tumult of the last year.

I worked an average of 2.93 hours per day, median 2.75 hours. I wrote the typical daily entry above as an example before I analyzed the data. Turns out, that’s a pretty good idea of what I do every day. I read a little, write a little, market a little.

By the projectThoughts about the dataReading, as always, takes the number one spot. I’m always hesitant to include it—it feels like padding my hours. But I’ve found it useful to include for a three reasons:

It encourages me to read more. I hate to say it, but the pull of social media is strong. Having another reason to finish a book that is boring but necessary for story research helps push me to finish it.Since 2021, I’ve started taking heavy notes on every book I read. What the book made me feel/think, where it made me feel/think, and why I think it made me feel/think. Story notes, criticism, or thoughts on how the book is relevant helps me put into words how my own stories fail or succeed while they’re in the draft stage.Reading often is critical to writing well. Making space to read furthers my goals of writing something great. Writing reading notes makes me a better writer and feeds into my TikTok reviews, which also make me a better writer and helps me sell books, which helps me keep writing and reading…. I can’t untangle reading from writing. Thus, I include it.Perceiver 2 at #2 with almost 220 hours! Seeing all the hours spent at my desk condensed to a statistic shocked me. Eventually, I’ll have an official name to declare.

Social Media should really be relabeled TikTok. I did not imagine my TikTok channel would grow to this extent. I started it like I started all my other social media channels: to maintain some kind of presence on the internet and thrust my book in the faces of strangers. But it turns out people like my weirdo reviews. Before I could blink, I had about 3,000 people following me, and some sales, opportunities, and cool connections. I’m still fleshing out how I should track time spent reviewing and creating videos, but I intend to track it as seriously as I do everything else. Eventually I’d like to write about how TikTok has changed how I write and tell stories and how people find and read them.

Diary… I felt uncertain about including it as part of my system. Writing in my diary helped me stay sane during lockdown. It was easier to record what was happening than squeeze fiction straight from my overheated brain. I pieced together stories from its pages and used many of the thoughts, feelings, events, and dialogue I recorded verbatim. I’ve also written blog posts, parts of short stories, and TikTok scripts as part of filling out my daily three pages. Despite what I choose to write and the size of the journal I wrote in, the fact is, I wrote three pages a day this year, and I didn’t miss a single day. But next year, I won’t be including it as part of my writing system. I’ve included writing in my diary in this review for posterity.

Writing Group! I have been a part of a talented group of writers to swap manuscripts and share advice. I track the time I spend looking over their work, attending the weekly meetings, and getting my own work critiqued. Getting regular feedback from knowledgeable sources is key to improving.

The other projects not listed include many short stories you’ll see in the coming year.

Here are the resolutions I made for 2022. The ones I reached are in bolded.

2022Hard goals3 pages of fiction every day. This time, I’m not going to count the diary as 3 pages.3 pages in my diary every day.Add hours to my time-tracking app at the end of every week. Publish Perceiver 2 before the end of the year.Soft/Stretch goalsDon’t spend more than 15 hours on a 4,000-word short story. 20 hours for a 6,000-word short story.Take 5 short stories from draft to done, as a stretch goal. I’d like them to be under 4,000 words each.*Thoughts on 2022 goalsWhy do I think I didn’t make these goals? I think I was underestimating the lingering effects of the pandemic, burnout, and overwork from the previous year. I always aim high, because I don’t want to go easy on myself. Yet, I hadn’t let myself truly rest. When I didn’t hit the numbers, I felt discouraged. This video explains my feelings perfectly.

Failing to meet arbitrary goals I set for myself made my self-esteem and self-respect conditional on meeting those goals. I berated myself for not working hours every day, not using every scrap of time to its utmost. Focusing on productivity made me overly selfish and self-involved. I’d resent family and friends for reaching out to me, or me reaching out to them, and then I’d feel self-reproach for feeling that way. How much I enjoyed something was not something I included in my tracking, and there was no room for things like rest, funerals, sickness, and vacation.

But the numbers don’t tell the whole story.

I resold a story to an anthologyI got interviewed on a podcastI got on and gained nearly 3,000 followers in 6 monthsI finished a new draft of my sequelIn my personal life, I got a new remote job doing what I love (with a 30% raise!)I got into weightlifting and dropped a whole pant sizeI’ve learned so much about writing and storytelling that my views on what I want to accomplish with my art has transformedWhile I can’t say that I’m happy that I’ve fallen short of the goals I’ve set for myself, this year is far away from a loss.

So what about next year?

Thoughts on 2023 goalsI usually decide daily resolutions by November, and test them out for the month of December. If I don’t think they’re feasible, then I tweak until I can do them daily.

I first set my usual— 3 pages every day. The 3 pages were hard. I exchanged my tiny diary for the A5 journals I used in college and returned to fiction. It wasn’t the size that was a stretch. It was the reworking of disused muscles, to generate material rather than pull it unfiltered from life. But it felt good to return.

I also wanted to set a daily goal of an additional 1000 words or 1.5 hours of editing/revision/or some other necessary task. Too much. I dropped to 750 words/1 hour after the first week of December. Then got my ass handed to me one hectic week at work and realized I depended on work being slow to add 100 words here, 250 there. But I can’t count on that being the case every day. I finally dropped to 500 words/30 minutes in the last two weeks of December. I can always try to add more later, when I get used to the load.

As for TikTok, I originally started my channel to promote my work. I’m still uncomfortable telling people to buy my books and read my stories. But this year, I want to become more comfortable talking about my writing online and enticing people to support me. So, I’m setting a goal of one writing update vlog-style per week, tying my current writing projects to what I’m learning with these books on writing and storytelling. Plus, one review on a book on writing and storytelling per week.

2023Hard goals3 pages every day. The diary will no longer count.500 words a day OR 0.5 hours of writing/editing/revising that isn’t the 3 pages1 weekly vlog with writing updates1 weekly review on a book about writing and storytellingAdd hours to my time-tracking app at the end of every month (I’m going to try this one again, with some key habit changes to make sure I stick with it)Soft goalsSend Perceiver 2 off for editing5 short stories from draft to done (I’m going to try this again)10,000 followers on TikTokReview another 26 books on writing and storytelling (right now, I’ve reviewed 26, or one a week since I started my TikTok.) Concluding ThoughtsWhen I try to think of an anecdote that sums my year tidily, I can’t. Maybe it’s this one:

The editor of the magazine that published “Singot” and “The Heebie-Jeebie Beam” emailed all the authors who had been published in his pages. Awards season was upon us, and if they wanted him to nominate them for anything, to please let him know. If you’re unfamiliar with the backstage workings of the science fiction and fantasy literary community, you might be taken aback that such blunt promotion is acceptable. But it’s a thing. And it always pits my god complex against my imposter syndrome. Do I say, “I don’t know if my work is good enough to be awarded”? Or, “I’m happy that you’ve considered me”? Do I say what I want the editor to do and want myself to believe? “Nominate me for everything! My work will serve you your own heart, and you’ll eat it and thank me later”?

I don’t just want to be good. I want to be seen being good. Those are nice dueling phrases. I wish I had thought of them myself instead of paraphrasing them from Zadie Smith, who had everything I wanted happen to her at the age I wish it happened to me.

Especially because, at that age, I was hoping to be saved by my career taking off. Awards, residencies, prizes. Especially cash prizes. I was living at my parents home, one sick in an socially unacceptable way, and getting worse. And I was wasting my college degree toiling in a museum gift shop that paid me just enough to buy the gas to get there and back to the cage called home.

One day I heard from a friend that another friend had won a national writing competition with her first published short story. At the time I was sitting in my car in a freezing parking garage, reading a list of magazine rejections. My parent had just been admitted to a psychiatric facility. I’d just been rejected from the upteenth job that could have rescued me. And I read the first few pages of the short story and couldn’t finish the rest. It was great. Great in a way my stories were not. I cried.

When I got home and sat down to write, I wondered what the point of it was. I had always known, in the way I know the sun will rise and set, that expecting to get rich through writing had incredible odds. Yet, it wasn’t until circumstances had lifted me out of daily life to see the world turning that I realized I hadn’t really known it.

Martha Nussbaum, my favorite philosopher, once said, “Knowledge of a thing is not the same as experience of a thing.”

OK, I thought. If I’m never seen, never spoken to—if nobody reads my writing, if I never write something incredible, something that sees and speaks to someone, if all this came to nothing, and if I knew it would come to nothing, would I stop writing?

No.

Why?

IDK. What else would I do? I couldn’t come up with a better answer than another question. The fact is, there is nothing else that captivates me more than writing. There is nothing else that makes me feel like I’m doing the right thing than writing. I don’t have anything particular I want to say except whatever I feel like saying that day, and the causes and crusades I embark on pale in comparison to the fierce urge to tilt at the windmill called writing. I experience this every day when I sit down to write.

That was five years ago. What saved me was time and persistence. I got a new job, one which paid me enough to move out with a roommate. The parent got on a new medication, which worked. And also, the people who gave me references, and who sympathized with me with their own stories and helped me through it all. The sun rose and set dependably, as it always did.

And here we are again, completing another lap around the sun. Several spectacular things happened to me this year. I resold a story to an anthology. I got interviewed on a podcast. I got on TikTok and discovered that there was a form of social media that I wasn’t just good at, but also loved doing, and also had people who were happy to watch me sputter and clown about. Despite 12 years of writing every day, I never expected to be seen, let alone spoken to.

When I hesitantly named the awards that I wished to be nominated for, the editor told me, “I’ve already nominated you for those.”

I am excited to see what the next year brings.

See you next year!

See you next year!The post 2022 Year in Review appeared first on EC Fuller's Books.

September 5, 2022

Story Inspiration: The Heebie-Jeebie Beam

I have an exciting update to share with everyone~

My short story, “The Heebie-Jeebie Beam”, has been accepted by Metaphorosis Speculative Magazine and is in the July 2022 issue! You can read the story here.

This is the second short story I’ve placed with them (the first being “Singot”). Like my previous inspiration posts for “Singot”, “The Hole in the System”, and Perceiver, I wanted to talk about why I wrote “The Heebie-Jeebie Beam”, what I learned about my writing process while writing it, revising it, and working with the editor of Metaphorosis to publish it.

InspirationFirst thing to know about me: I take a really, really long time to write short stories. “Singot” alone took over 80 hours from first draft to published manuscript. That’s longer than it takes for me to revise a draft of a novel.

Why was I so slow? Before writing “The Heebie-Jeebie Beam”, I identified more as a writer than a storyteller. I could write a mean sentence, but I lacked the ability to sense the elements of a good story underneath. Because of that, I often got stuck when writing. I didn’t have a sense for the story, for what needed to be fleshed out, what could be skipped, what details were the most important, or how to create momentum. I revised as if rooting the words from mud, blindly searching for them. What was holding me back was something enormously simple and obvious in hindsight.

I didn’t know how to get better or faster until fall 2021, when I stumbled across two strange musicians on the internet. One had an afro that tripled the diameter of his head. The other had a porn stache and wore silk robes and boxers on stage. Both of them went on stage without knowing what they would play. No set list, no sheet music, head empty.

If you recognized them, bravo. Please be my friend. For the rest of you, these two were Messiers Reggie Watts and Mark Rebillet. It would be easy to call them musicians, because the usual outcome of their work is music. They use loop machines, synthesizers, and mixers to create loops of beats, rhythms, and other sound patterns, which they then sing over. But the product is pure astonishment.

I had a thought watching them improvise together with Flying Lotus, each man in a nest of wires and machines, making the most incredible music based on nothing but energy and response. How is it that people can make something up on the spot AND have it be coherent and engrossing and awesome? As someone who practices what she’ll say to the barista before she orders, going on stage unprepared was the stuff of nightmares.

I knew I had to try it.

I took an online class hosted by Watts, but I don’t remember most of it. I do remember that it was about responding to the material that’s already there, rather than editing endlessly. As performers, Watts and Rebillet can’t take back a sound. Once it’s out, you have to do something with it. So it was important to listen deeply and keep an open mind.

But writing is different. Unless you’re a spoken word poet, most writing is rewritten. Often multiple times. How could I apply what I had learned to writing stories?

Around that time, I had read two important books on writing that influenced my thinking. The first book was A Swim in a Pond in the Rain, by George Saunders. His advice echoed what I had learned from Watts and Rebillet.

Be honest about what you think and feel.Be responsive to what’s there.But Saunders also added a crucial third element:

Always be escalating.The second book was Lisa Chron’s Story Genius. Her definition of a story made everything click: A story is about a character striving to do something difficult and how they changed inside as a result.

Because I like being publicly humiliated, I’ll admit it: I didn’t know what a story was until I read her book. Nobody had spelled it out for me. It’s like trying to understand what the sky is. I mean, you and I can recognize a story from twenty paces. But as every reader knows, when you see it in words, it’s life changing.

So: I wanted to test what I had learned about storytelling from Chron and Saunders, but also Rebillet and Watts. I also had other pressures upon me. For my 2022 New Year’s Resolution, I vowed to let no story take longer than 15 hours from draft to done. On top of that, I had twice asked for an extension from my editor for the sequel to Perceiver. It’s due after Thanksgiving. I’m still working on it, as of this writing.

I didn’t realize it then, but what I was truly testing was a core belief: that writing does—and should—take a long time to write and revise for the finished product to be great. If this experiment worked, it would fundamentally change how I wrote.

All I needed was a starting element. An opening note. A beat.

Good thing I had one.

The Writing ProcessI had been obsessed with the phrase “heebie-jeebie beam”. Something about that short-long, short-long, short phrase with a three-in-a-row internal rhyme, the silly phrase “heebie-jeebie”, and the intriguing “beam” caught my imagination. The theory of aspiration, or the philosophy of trying to become a certain person (especially the book by Agnes Callard), weighed on my mind too. More on this later.

I thought, what about a ray gun that transforms people? What kind of person would make a gun like this? How would it work? Who would need it the most?

And I was off. The story came out like a river. My editor brain turned off. I threw in the first words that came to mind: oodles, frick, cromulent—rather than their plain language counterparts. I used that funny saying I’d been saving—the challenge forced me to use everything I had been holding back, and I was surprised and excited by what came up.

Later, I read a book titled, “If I understood you, would I have this look on my face?” which is about how to be better at communicating science. It’s really a 245 page plea for people to take improv lessons. What I learned during the first draft (and later, when I started taking lessons) was that improv teaches several crucial skills.

It teaches you how to be responsive to another person—listeningIt teaches you how to build on the material that’s there—resourcefulnessIt teaches you how to let go—fearlessnessThe first draft of the Heebie Jeebie Beam took 7 hours total to finish. 8 hours to revise and workshop.

Revising was similar to writing, except that the material changed. Though I’d set out to write something fun, I couldn’t help but think more seriously about the Beam itself. How would the raygun change people? Fear, was what I wrote. What kind of person makes a raygun that frightens people? Why do we feel fear, and how far would we go to stop ourselves from feeling afraid?

The protagonist is not a self-insert character by any means. Yet, to write them, I had to take census of my own fears, even the ones I was ashamed of.

Back to Agnes Callard. She wrote a book called Aspiration, which was about the philosophy of trying to become a certain kind of person. “The aspirant makes pictures of himself in order to resemble the picture.”

The aspirant has a vague idea of the person they’d like to become, like you have a vague idea of what you look like in a foggy mirror—but what that person values, how they act, what they believe is ill-defined. They have to act as if they value, believe, etc, before it becomes authentic, i.e., fake it ‘till they make it.

For me, aspiration was a serious business. I’d identified as a writer from a very early age, fixed my estimation of my intelligence on it, did (and valued and believed) several stupid things for the sake of being a writer. Especially that the more time spent writing and editing something, the better. An aspirant is someone who tries to become someone they’re not.

Trying to become someone you want to be can go two ways: you can become someone who would inspire others and awe yourself. Or, you can warp yourself to fit an image you were never meant to take.

Like I said, in middle and high school, I took pride in being smart and competent and being seen as smart and competent.

What I didn’t realize that everyone thought I was too—forgetting that I was a child.

A close family member had regular bouts of anxiety, depression, and psychosis. Every two years, some malicious timer in their brain would click and a bad brew of chemicals flooded their mind. They did many of the things the mother in the story did. Like the protagonist, I took a disproportionate burden in making sure they were okay.

I tracked visiting hours in the psych ward. I drove them to the hospital more than once at night. I called the police. I just did it. I researched the COPES line, the research on depression, how to keep people calm during a mental health crisis. I got good at that.

I thought I could self-improve myself into fixing someone else. In hindsight, a stupid thing to do.

Sending off the storyAfter I revised the story for clarity and streamlined or expanded some scenes, then sent it off to my writing group to workshop. Overall, they enjoyed it. After addressing their comments, I sent it off to short story magazines that I thought would be a good fit.

I got an automatic rejection from the first magazine I sent “The Heebie-Jeebie-Beam”. It was also the best-paying magazine. Wah. But I caught the mistake and sent the short story off to my second choice. I got a personal rejection with feedback, which made me feel pretty good. The third magazine was Metaphorosis Speculative Magazine, who offered an acceptance contingent on rewrites.

I knew when I agreed to revise that I wasn’t going to make the 15-hours-or-less challenge. The magazine’s editor, Morris, pays lapidary attention to every part of the story. This meant a few rounds of editing and more hours of work.

Yet, I learned so much from the process of revision that I would happily do it again.

The Editing ProcessThe first round of editing started with a short paragraph of comments over email—no comments in the document until I addressed the overall.

Morris pointed out three major problems:

The relationships in the story needed workWhat happened to the mother was unclear—was she ill or had something happened to her?Why had the father left? What did the protagonist, Will, think about him leaving?This was more or less what my writing group and the second magazine had pointed out. I thought I had addressed those comments, but apparently not enough.

When you write a story that is heavily weighted towards the theme or philosophy, it’s almost structured like an argument (at least, that’s how I think of it), with a thesis and points and counterpoints. But the argument is based on the character(‘s) experience. And people build their philosophies of being based on how they are treated—aka, their relationships. So my first thought was that I needed to:

Add flashbacks, details, and other experiences that reveal the parents’ characters andDo in such a way that showed the protagonist’s changing attitude towards themThe thing about working with editors is that they’re really good at asking questions that you ought to ask of your work. Really good editors ask the unconscious questions readers have when they read. Six drafts I sent to him returned highlighted with comments; not a single paragraph was unexamined.

(By the way, if you want to read about how this magazine goes about its editorial process, it tells all in the anthology here.)

I failed the 15 hour challenge spectacularly. But I will try again.

The EndSomething I learned while researching for the story was that emotions show you what you value. Fear tells you what you are afraid to lose.

During the pandemic, it was deeply difficult to write. I kept up my three pages, but they changed to diary pages, in tiny notebooks. When I wrote during that time, it felt like I was writing with my own blood—it scared me, how much something I loved drained me and how little I had to give. I felt there was something lacking in my own work—some fundamental energy—that makes stories breathe, shake out its wings, and soar.

“The Heebie-Jeebie Beam” is the fourth short story I’ve ever published, so I wasn’t expecting a huge response. But all of the responses validated the exact thing I was aiming to achieve with the story—that readers thought about it long after it was over, and they went back to reread it to find more things to think about. It’s funny, that the thing I thought would take me away from writing the stories I want to write brought me closer to them. Reading those books and watching improv changed my understanding of what was needed to create something good. It became easier, more joyous to write, though my process has changed radically.

The last line of the story could not be anything but this: “Fear lets you know you’re alive.”

Again, you can read the story here.

The post Story Inspiration: The Heebie-Jeebie Beam appeared first on EC Fuller's Books.

June 24, 2022

TikTok Announcement

So I’m on TikTok.

@longhandhabitsAnd my library grows… #booktok #writingbooks #booksonwriting #writingtok #writing #storytelling #bookreview #bookthoughts #bookrecommendations

♬ original sound – laufey

I post reviews of books about writing, craft, storytelling, and other related topics. Plus, I also post short videos on tips to help you write tighter, tell stories better, and how to improve. I don’t claim to know everything–these videos aren’t prescriptive–rather, they’re meant for viewers to take what is useful to them. I might not be the best writer in the world, but I’m further along than most. And I’m only getting better.

I’d always heard about how TikTok is great for sales if you’re a book publisher (cough). But when I first encountered it, I didn’t know what I would do. In early January, I had toyed around with unboxing videos from stationery shops. Yet they felt silly, and I worried that I would have to keep buying stuff to make the videos. The basics of social media content are to post things that are entertaining, educational, or inspiring, preferably all three. At the time, I didn’t think I had anything like that. I contented myself with watching chefs scrape their expensive knives on perfectly crusty bread and tattooed girls shave rugs.

But then I remembered my book notes.

In the summer of 2021, I bought a book called, How to Take Smart Notes. The book claimed to teach a note-taking system which went beyond productivity and freed the mind to do what’s important: think, understand, and write. Moreover, the book had evidence-based practices for learning how to learn, how to manage your discipline, how to read, and more.

The book immediately caught my interest because it claimed to solve a problem I’d been struggling with. Namely, that I have systems for productivity, but productivity does not equal insightful, quality writing. I knew How to Take Smart Notes would be helpful for the more research-heavy stories, but I wasn’t sure how to finagle it into something for fiction. I thought that if I forced myself to take notes as I read, then I would theoretically be a better reader, better able to articulate my responses to something when reading.

@longhandhabitsHere’s my review of it.I use this system a little differently, but it works really well for writing fiction. #howtotakesmartnotes #sonkeahrens #notetaking #studytips #writingtips #studysystem #howtoimprove #productivityhabits #bookthoughts #bookreview

♬ Motivational – Azwar

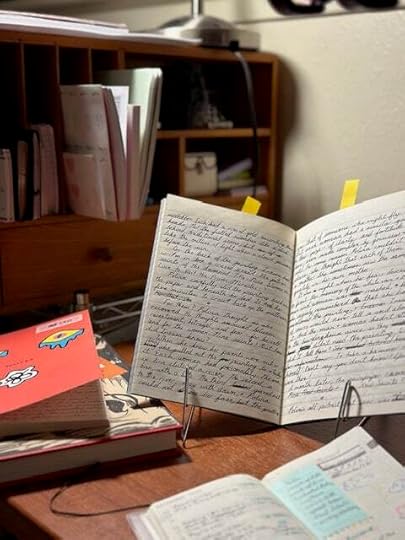

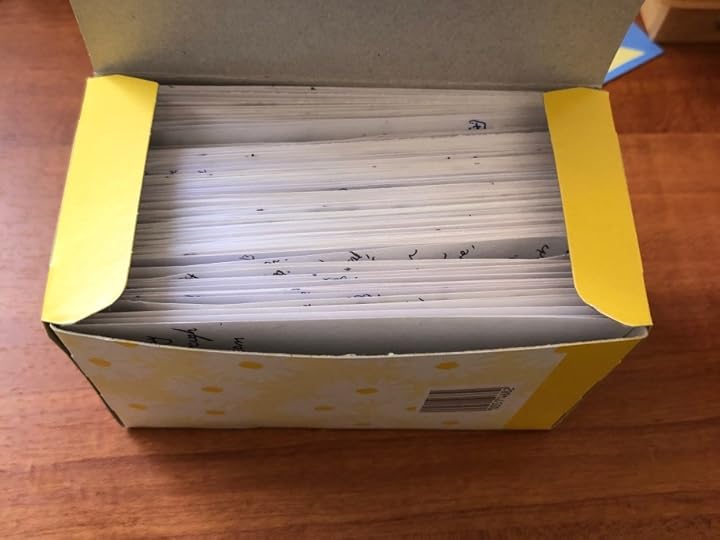

I threw out all the free bookmarks littering my apartment and replaced them with blank 5×3 index cards. I used those index cards as bookmarks and write on them as I read, frilling my books with page flags. When I finished reading, I summarized the book, my thoughts, impressions, etc. I kept the finished cards in an empty tea box from Trader Joe’s, hoping I would hit critical mass and come up with an amazing idea of staggering value and entertainment. In reality, I used them sometimes for blog posts and rarely looked them over.

Book notes in chamomile tea box from Trader Joe’s

Book notes in chamomile tea box from Trader Joe’s 5×3 index cards fit perfectly inside

5×3 index cards fit perfectly insideJune 2022: My roommate went out of town for two weeks. I was bored and alone. That was, of course, the prime environment for shenanigans. I thought, my second book is due to my editor in late July. If I don’t step up my social media and marketing game, I’m not going to sell anything. I challenged myself to post—anything—at least one video a day. I realized that one index card of notes, front and back, was about 60 seconds of voiceover. And then I was like—holy crap, I have a year’s worth of content in that beat-up little Trader Joe’s box.

I knew just doing book reviews wouldn’t help me stand out. There are so many book reviewers, you need to have your own niche within BookTok. But even then I had an edge. I have tons of books on craft, writing, poetry, writing exercises, storytelling, editing, publishing, you name it. I got to work.

So here’s how it usually goes. I have a book on writing or storytelling, and I make a 60 second review. Then, I do 15 second videos on a writing exercise, tip, quote, or something in the actual book—anywhere from 1 to 3 of these. My channel also has shorter videos on writing tips, challenges, and advice.

I created the channel because I was bored. I kept it up because it helped me. I’m keeping it going because I want to share all the writing and storytelling knowledge that I wish I had.

You can follow me here or on TikTok for more! The monthly newsletter for this blog gives exclusive deals, updates on upcoming books, and insight in my writing.

The post TikTok Announcement appeared first on EC Fuller's Books.

January 21, 2022

2021 Year in Review

What did I achieve? What did I miss? What went sideways, and what pleasantly surprised me? This is the data-backed story of 2021.

If you want to check out my previous reviews, see below:

By the NumbersI track how much time I read, write, edit, and work on things related to writing. Each time is rounded up to the nearest fifteen minutes. I first track longhand using a weekly planner, with notes on where I worked, special events, appointments, and other activities. Then, I upload the numbers into an app called atWork. At the end of the year, I upload the data, clean it, and analyze it using Google Sheets.

Comparison Between YearsIn 2021, I worked 1147 hours and 45 minutes.

I worked an average 3 hours and 8 minutes per day and a median of 3 hours per day.

The most I ever worked in a day was 7 hours and 30 minutes! I was only able to do it one day this year. The least I ever worked in a day was 15 minutes, which I did on two days. No zero days!

Hours per WeekMuch easier to read, right? There are clear peaks and valleys throughout the year.

I worked an average of 22 hours and 20 minutes per week and a median of 21 hours and 30 minutes.

The most I ever worked in a week was 30 hours and 30 minutes. The least, 18 hours and 15 minutes.

Hours per MonthI worked an average of 95 hours and 38 minutes per month and a median of 103 and 22 minutes.

The most I ever worked in a month was in May: 108 hours and 45 minutes. The least, in August, was 65 hours and 45 minutes.

Summary of NumbersI tend to be productive when I’m working in the office, have an easy workload, and aren’t dealing with family emergencies. When the U.S. started opening up after lockdown, I worked in cafes, I rode my bike to the library, and felt safer doing it. Hope that things would get better buoyed me above the clouds of anxiety.

Do I need data to know this? Of course not. Do I like having data to back up my suspicions? Of course. I track this way because it keeps me honest about where my time is going. It also helps me understand how to best position myself to make the most of things.

But this year confirmed something repeated in the news, on productivity and business blogs, and in my own life: much of what goes into having a productive day is not controllable. Productivity is really about attention. Where to place my attention, how long to place it, and the quality of that attention matters a great deal in finishing projects. But when life is an alarm clock with a broken mute button, attention shatters. My Dad passing away proved this.

When I took bereavement leave from work, I took bereavement leave from writing too. I couldn’t write as much as I normally could and support my mom simultaneously. Part of being a professional means knowing when to put your work down. I knew I would never permanently put my writing down. Remembering all the things my dad did to support my writing made me even more determined to get back to it.

By the ProjectI used to divide my time into simple categories: writing, editing, research, reading, etc. As part of my 2021 New Year’s Resolution, I changed to a project-based system.

Boy howdy, I’m glad I did.

Those wafer-thin pie slices are tasks or projects I worked on the least: website maintenance, marketing, research, and time-tracking, as well as a few short stories I tinkered with off and on. Slices larger than 1% of the year got a label: submissions, “A Hole in the System”, “Singot”, etc. The top five projects I worked on (or 78% of my year), tell a better story.

ReadingI track my reading hours and count them towards writing. Why? Reading expands the tools and approaches I can bring to my own work and refreshes my imagination. For example, sometimes when I’m stuck on a scene in my own story, I’ll read something that demonstrates the thing that would fix my problem. Reading criticism and writing advice helps me think more deeply about what I write and why, and how one approach or another changes a story’s meaning.

And also—I hate to admit it—tracking how much I read helps me stay off social media.

I don’t track by the number of books I read. This year I started taking notes when I read (replace your bookmarks with index cards, people!). Thus, it takes me longer to finish a book. Fine with me. If I don’t retain anything, what’s the point of reading it? Or, if I’m not paying attention to the words, am I really reading? Or am I mindlessly consuming?

Perceiver 2The second biggest project was the sequel to Perceiver. Unfortunately, due to my dad’s passing, my cousin’s wedding, and just recently, a nasty car accident, I’ve pushed back the date to turn in the manuscript to my editors. On top of that, I took the story in a brand new direction, which means a ton of scrapped chapters and major revisions.

The good news is, the new direction has lit a fire under me. When I plonk down at my desk and put pen to paper, the story feels like it’s guiding my hand. It’s a rare feeling, and it always means that the story is going to be great.

DiaryThe third biggest project is my diary. I didn’t regularly keep a diary until 2020, when I found it difficult to keep up writing fiction during lockdown. Whatever snowmelt that had fed the spring of my imagination vanished. To keep up my three pages, I filled progressively smaller notebooks, swapped from writing novels, to short stories, to sketches of pandemic life.

Now at the end of the second year of the pandemic, I wonder, should I continue to add it to my writing projects? I think I will. The diary acts like a compost heap or a thought trap. When I skim through the pages, I feel like I have a better idea of what I pay attention to and who I try to be. Sometimes I’ll reread a past entry and think, “There’s something to that.” And that entry becomes fertile soil for a short story…..

Plague of Doppelgangers…like “Plague of Doppelgangers”. About 6,000 words long as of today, the story has taken just under the amount of time to completely revise a draft of a novel. It still isn’t published. I’m still working on it. Why the h-e-double-fuck is it taking so long?

“Doppelganger” developed concept-first, and the characters and story came second. I completely scrapped and rewrote several drafts of the story before I found one that I stuck to. By comparison, “The Hole in the System” was also concept-first, but the story came easily. The Hole took just over 20 hours to finish and publish.

I still believe in “Plague of Doppelgangers” and the idea behind it. Editors and my writing group who have seen early drafts see where it sparkles, even as they can point out where it can be polished and where it’s too rough to be published. I think about it often and I’m not ready to let go of it—I’m still having fun.

That said, it’s time to move on. If I can’t improve “Doppelganger” within another 10 hours of work, I’m going to call it a learning experience and move on.

BlogI worked on a lot of blog posts that never saw the light of day, which is inflating my numbers. Or ones like the Year in Review, which required a lot of analysis and thought. I think I’ll probably do something to what Brandon Tyler does on his substack. Thoughts and vibes. Occasional reviews.

Other ProjectsThe next top five projects with the most hours went to Submissions to writing residencies, magazines, contests, and more (59 hours), then Writing Group critiques, board meetings, and workshopping (51.5 hours), “Singot” (26.75 hours), “The Hole in The System” (22.75 hours), and Miscellaneous (15.5 hours).

I’m mostly fine with this. I don’t think I’ll submit to more residencies or contests this year because 1) submitting gets expensive 2) residencies want essays on top of fees, which means they’re an even bigger time suck. I don’t want to do a virtual residency or spend the time revising the applications only to have the residency canceled because of COVID. I also don’t have a large portfolio of published short fiction less than 4,000 words to submit as samples. I’ll just take a week off of work and write at a cafe or library.

I’d also like to spend most of my time (top five projects) working on fiction, short and long. I could have done better with tracking what I did for each project. For example, how much time I spent revising each chapter for Perceiver 2.

Summary of ProjectsHere’s the thing to keep in mind with this insane tracking. Productivity isn’t measured in how much sand is left in the bottom of the hourglass. Effective productivity is a low ratio of what you put in and what you get out.

But much of what feeds a story is unquantifiable. Reading the right book at the right time; something weird happening that kickstarts an idea; someone cracking wise who becomes that character you need. Nobody can engineer destiny so that the thing you need plops into your hand, fully formed and ready to be massaged into your story.

But everyone can practice. And what is practice but making the basics a habit? As I’ve grown as a writer, it’s become easier to self-identify problems with my writing. The stakes aren’t clear. The characters aren’t making sense. The tension has slackened in this scene, and this other scene is good, but it doesn’t work with the rest of the scenes. Through practice, I’ve learned how to identify problems, and I have a larger mental toolbox of solutions.

In other words, I spend less time moaning, “How can I fix this?” and moving words around without improving the story. Instead, I just fix the story.

It takes time to learn how to write fast. I’m still learning.

GoalsHere are the resolutions I made for 2021. The ones I reached are in green; the ones I didn’t, in red.

#Project focused time tracking, rounding up to the nearest 15 minutes.

3 pages a day

Hire a cover artist for my first book

Publish my first book

Find beta readers for second book

Hire editors for second book

50 magazine submissions, stretch, 75

Stretch goal: publish second book.

I kept my goals low. If 2021 was anything like 2020 I wasn’t sure if I could keep them. But the only goal that I didn’t make was the 50 magazine submissions. I submitted 16 times. But I didn’t make this goal for an awesome reason: the short stories I submitted only had one or two rejections. I was expecting 15 a piece!

For 2022…

Hard goals:

3 pages of fiction every day. This time, I’m not going to count the diary as 3 pages. The diary will be its own daily thing. The 3 pages will be focused on fiction, blog posts, or other publishable work.3 pages in my diary every day.Add hours to my time-tracking app at the end of every week. I got lax during 2020 and I’d add my time in huge bursts every month or so.Publish Perceiver 2 before the end of the year. Knock on wood.Soft/Stretch goals:

Don’t spend more than 15 hours on a 4,000 word short story. 20 hours for a 6,000 word short story. I gotta’ curb that bad habit.Take 5 short stories from draft to done, as a stretch goal. I’d like them to be under 4,000 words each. Most residencies, grants, magazines, etc tend to stick to 4,000 words as a limit, and I tend to go over it. If I can finish 5 this year, I’ll be happy.Adding my hours up every week will be key to making sure I don’t go over. Gotta’ keep an eye on the hourglass. Concluding ThoughtsHere’s the easy-to-grok & undeniably good parts of 2021: I made it to 11 years of writing every day without missing a day. I hit most of my goals from last new year’s resolution. I published two short stories and a novel. The sequel to the novel is being briskly written and edited, in no small part because I finally understood something crucial about storytelling, something that I’ve somehow missed in 11 years of writing every day without missing a single day. To use Lisa Chron’s definition, “A story is about how the things that happen affect someone in pursuit of a difficult goal, and how that person changes internally as a result.” This lesson didn’t sink in completely until after August 4th, 2021.

This was the day my Dad passed away unexpectedly. August 4th was shortly after “Singot” was published and shortly before “The Hole in the System” and “Perceiver” were published. Dad never read these stories. I don’t know if he ever read any of my stories. It kills me that I didn’t share them with him. Especially because he had shared his with me first.

One day in 2018, he handed me a pair of flash drives with a trio of short stories he had written about the time he was in the Coast Guard. “Maybe you could do something with them,” he said offhandedly, over his shoulder, as he shuffled back to the recliner to watch a WWII documentary. “I just thought you’d like to have a look. Maybe clean them up and do something with them.”

I couldn’t imagine Dad as a writer. First, Dad was Dad. Then, hobbyist airplane maker and flyer. Professional airplane building, capping over 30 years at American Airlines as an avionics engineer. He wrote articles for airplane magazines, but even that writing was wrapped up in aviation.

When I think of him, I see him working in his workshop, a big building in the backyard filled with sanders, drillers, a 3D printer, an industrial printer, smelling of sawdust, paint, and airplane glue. There’s yellow light thrown onto the dusk-dark lawn, and through the window on the door I can see him passing wood through a bandsaw, pecking at his computer, or arranging the airy internal structure of an airplane wing. The silver hair on his arms is always powdered with sawdust.

I assumed he was born on an airplane. He rarely talked about his life; hell, he rarely talked. While digging through Dad’s desk for legal documents to send to the funeral home, we found his discharge papers. Dad had received a Silver Award, one of the highest honors in the Coast Guard, for rescuing people from a burning boat.

The two flash drives held the greatest quantities of his interior life that I would ever read in one sitting. I was afraid they would be great. That he was an undiscovered talent, the way I hoped I was. I was afraid they’d be terrible. That he wasn’t worth knowing. I was afraid that he would be a different man than I thought he was.

But I wanted to know him. I plugged in the flash drives and started reading.

Sometimes when I read, the author captures a feeling or thought so familiar that it gives me the feeling that someone is watching me. It jolts me. It’s the author seeing me through the fence of their sentences and speaking to me.

Reading Dad’s stories was a reversal of that feeling. It wasn’t exactly his voice. It was the voice of someone who was trying to write like novels he liked to read, nonfiction military biographies and first person war stories, all bravado and military jargon. But it was Dad, undeniably.

The first story I read was titled, “My Most Memorable Rescue.” The first paragraph is as follows:

“My most memorable rescue wasn’t the most spectacular or most dangerous rescue I was involved in. In fact it could have been called a really ho hum rescue. What makes it memorable to me was not only the fact that it was the day or so before I got married, but also the response of the kids I had picked up that day.”

He had been called out with his rescue crew to Crystal Beach, Texas when a couple of kids were blown out to sea in their inner tubes. When the chopper zoomed over the kids, he saw their faces light up. Wow! We get to ride in a helicopter! And when he and his crew returned to shore, the community had gathered on the beach. Sand billowed from the chopper’s downwash; clothes flapped against chests, baseball caps flipped off heads, hair lashed their shoulders. And when the boys were released onto the beach, the boys’ mother swept them all into her arms and sobbed. Applause showered all around.

I’d seen a picture of him and Mom on their wedding day. He looks just about the same, but trimmer, dark haired, and sporting a mustache you could use as a boomerang. I can close my eyes and imagine the boomerang descending from the flame-blue Texan sky and returning, as if it had been thrown by God.

It was too late to ask the most flattering question you can ask a storyteller: “What happened next?” But that isn’t the right question anyway, because what happened next was already known. More kids happened: my brother and I. Then a house happened in Claremore, OK with a workshop in the backyard, and thirty-two years at American Airlines as a lead mechanic.

The real question was, why did this rescue matter to him? The writer side of me noted that these weren’t technically stories. They were anecdotes. An anecdote can be summed up as, “This crazy thing happened to me.” A story can be summed up as, “This crazy thing happened to me, and what happened changed me.”

Dad’s stories were about slipping his coworker exploding cigarettes, calling the officers “pukes”, and the long boring nights aboard a ship stationed in Alaska. They never culminated in an observation about humanity, a punchline, or a change in Dad’s psyche. Dad’s most memorable rescue never delves into why the rescue changed him.

There’s an obvious and comforting explanation to why the rescue meant so much to him. He had just been married; those kids could have been his. Though back then, I didn’t have the experience as a writer or the courage as a daughter to confirm why these stories mattered to him, I didn’t need to confirm. He bought me at least one book whenever we went to the bookstore, and I sit here among shelves ceiling high and shelves two books deep. He paid for the summer writing camps where I had the usual epiphanies of young artistic women, and the contest fees for contests I would win, or at least win honors. He encouraged me to go to schools and colleges hours away, if it meant I would get a better education, be around better people.

My brother and I were 3 and 4 years old when the workshop was built. Our handprints mark the concrete foundation, along with our ages, drawn with our fingers.

I often ask myself, “What is the story of Dad’s life?” Though I was his daughter, I didn’t witness a full half of it. The half from birth to age twenty-seven. The age he was when I was born. The age I was when he died. He never spoke about which events changed him, except these. Otherwise, why write them down? Even if he didn’t have the ability to craft what I believe to be a story—about how an experience changes you as a person—surely he did have stories. Because the alternative is that Dad’s life was an anecdote. A crazy thing that happened. Not even crazy. Ho-hum.

Around the time Dad had given me his short stories, I read Orhan Pamuk’s Nobel lecture, “My Father’s Suitcase.” Pamuk’s father had given him “a small suitcase filled with his writings, manuscripts, and notebooks” sometime after his father abandoned his family to be a writer in Paris. While writing this post, I reread it again, and the first two paragraphs shook me to my cells.

“Two years before his death, my father gave me a small suitcase filled with his writings, manuscripts, and notebooks. Assuming his usual joking, mocking air, he told me he wanted me to read them after he was gone, by which he meant after he died.

“‘Just take a look,’ he said, slightly embarrassed. “See if there’s anything inside that you can use. Maybe after I’m gone you can make a selection and publish it.’”

Pamuk had been afraid to read what his dad had written, because he knew what it meant to be given this a piece of yourself, shaped in solitude, at a cluttered desk, at an odd hour, to the one kid who would understand what it meant to be given a story, better than the writer-father understood.

And I’m remembering him again. It’s after sunset in my memory, as it always is. And he’s in the workshop, lights beaming out. Blueprints on the floor, sawdust hanging in the air, airplane parts scattered. He’s bent over the workshop table, building yet another plane, like he hadn’t been building real airplanes for his nine-to-five.

And I realize there’s only the present and the rest is imagination. I’m writing this now at my desk, as I always write these reviews. The sun descended hours ago, and my lamp looks warmly over my work. My room ripens with the odor of decaf instant coffee and the oils of sleep. There’s crumpled post-its cluttering my desk and carpet, and they say things like, “What questions do you wish you had asked Dad before he died? (why did these rescues matter to you) What are the answers you hope to receive? (because we mattered to you) When do stories resonate? (when they rhyme with your life).”

The story of our lives recounts the most dangerous experience we undergo—for nobody gets out alive. What’s worse is that most of it is barely worth writing down or remembering. But what makes it memorable are the people who descended into our lives and how they left themselves and us altered.

It’s the story of how we become ourselves through others.

See you in 2022.The post 2021 Year in Review appeared first on EC Fuller's Books.

November 14, 2021

Writing Confidently When You’re Insecure

You gotta be tough if you’re gonna be a writer. I submitted a draft of my application essay for an MFA program to my writing workshop. The workshop picked up on my uncertainty. I had previously had my confidence rocked by rejections from artist residencies, and it bled into my prose. But after revision, research, and preparation, I got over it. Now I truly believe the administrators would fight over me in a bare-knuckled boxing match under the nearest underpass for the chance to have me in their program.

I wanted to share the best advice I’ve received on Imposter Syndrome, concrete ways I revised my writing to sound more certain, and how I finally became confident of my work and acceptance chances.

The best advice on confidence hands down is from the Ask a Manager podcast, episode 23, “I Need More Confidence at Work”.

“Alison: When you’re dealing with this kind of confidence thing, it can really help to ground your thinking in paying a lot of attention to what the actual evidence is telling you. Meaning, take a look at what kind of feedback you’re getting from managers and from other people and look at all the evidence about what kind of reputation you’ve built. If you do that and you see that it doesn’t really line up with your own internal critique, sometimes that can set you on the path to building a more realistic self-assessment.”

In my grad school application, I took snippets from past performance reviews, praise, or other nice things people have said about my writing. I then circled questions from the essay prompt and built an accomplishment-cloud around that question.

I also edited out the qualifying language. Qualifying language, or hedging, is language used that makes the writer or writing sound more or less certain. Don’t qualify your accomplishments to be accurate. For example, don’t say, “I won a writing contest (but it was a local library contest (and there were only 100 applicants (and…)))”. If it can fit in parenthesis, or preempted with “but” or “however”, it’s best to leave it out. Qualifying language diminishes your accomplishments. Just say, “I won a writing contest.” That is accurate.

For my final editing pass, I reviewed myself through the viewpoint of a character named Personal Enthusiastic Friend (PEF). PEF is a character who’s been floating around in my head waiting for a story to call their own. I’ve conned them into being a better, braggier self for application essays. I adopt their voice when I’m writing applications and pretend they’re writing it, not me. To get into character, I write about myself in third person to further distance myself. Then, I swap to first person when I’m done editing.

Personal Enthusiastic Friend works in two ways. First, they make writing applications fun, and when it’s fun, it’s easier to write something with personality. Second, they trick me into viewing my own accomplishments more objectively. Weird? Yes. Works? Also yes.

But the thing that really got me over my uncertainty—the thing that made me think, I actually have a good shot—was going to the faculty and graduate student publication pages, checking out their books, and reading them. They write some weird shit! And I write some weird shit! And I thought, these are my people. They would like my stories.

Concrete preparation breaks down uncertainty. Revising your applications for tone, reviewing specific praise, and doing your research may not defeat Imposter Syndrome, but it vaccinates you against it. With a little help from your friends, real and imagined, you’ll rise to where you’re always meant to be.

The post Writing Confidently When You’re Insecure appeared first on EC Fuller's Books.

September 28, 2021

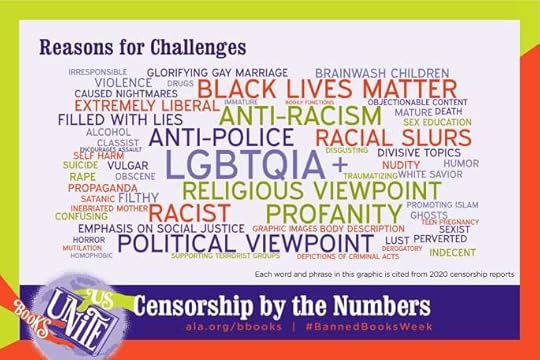

YA Cleanliness Rating System Rated Shit: Thoughts on Ratings and Bans

Recently, some agents and publishers for YA books received an email from a website called YA Book Ratings. The site’s admins asked them to rate their books on a ‘cleanliness’ scale and purchase stickers printed with the ratings to put on their books. The backlash from the writing community was brief but nasty, and the site went down like an inflatable boat with cactus passengers. It has since gone up again, but without the pages of ratings.

The whole thread is interesting.Our agency has received a request from this website to rate our clients' books for 'cleanliness,' a kind of moralistic gatekeeping that marginalizes young readers in a way I find really troubling.https://t.co/aZG5Iuhpgr

— Molly Ker Hawn (@mollykh) September 14, 2021

My initial reaction was, “There’s already Goodreads and StoryOrigin, plus tons of bloggers. Why do we need yet another rating system?” And, “If I was a teenager and a book got on the clean list, I’d know those books are boring.” Gimme your dirty, edgy, profane! Gimme the books you hide under your mattress and read with a flashlight! It wasn’t immediately obvious why people raged about the cleanliness ratings until I began to think more about it.

There’s a difference between what administrators of YA Book Ratings intended, what ratings actually do, and how this impacts children, teenagers, and adults.