Doug Sundheim's Blog, page 6

June 11, 2015

What Makes You Come Alive?

“Don’t ask yourself what the world needs. Ask yourself what makes you come alive, and go do that, because what the world needs is people who have come alive.”

— Howard Thurman – author, philosopher, educator

When I shared the above quote with a client, his reaction was: “It’s a nice thought, but a bit Pollyannaish for the real world. Some of us have tough situations and tough work to do.”

Fair enough. I get it. At first glance the quote does have a certain rainbows-and-unicorns feel. And I’ll be the first to admit that much of the “follow your passion” advice out there is banal and naive.

But I think Thurman is suggesting something different here. He isn’t saying that it’s merely nice to feel alive. He’s saying that it’s necessary in order to make the world work. When we feel inspired and engaged we give off a powerful energy. That energy is vital—not only to ourselves—but to our organizations, our communities, our families, and everyone else around us too. So it’s incumbent upon each of us to figure out what makes us come alive—and go do it. Far from self-indulgent, it’s a critical act of service in a challenging world.

Admittedly it isn’t easy to pursue what makes us feel alive. Many of us feel trapped by circumstances. We think our only options are to muddle through and cope. Feeling alive seems too wishful. How do you actually get there?

I wish I had an easy answer. I don’t. And even if I did, it probably wouldn’t be useful. Formulaic answers in this arena are always too simplistic. It takes guts to make the choices needed to feel alive. Everyone has to find his or her own path.

What I do have is a few hard-won insights. Habits of mind I’ve picked up over the past two decades as I’ve kicked and flailed in my exploration of what it takes to feel alive, helping clients do the same:

The signals are always there. You have to listen for them. The signals pointing to what makes you feel alive are all around you. However, they don’t grab you by the lapels, look you in the eye, and shake you. Rather they whisper softly in your ear, easily drowned out by all the other noise in your life demanding attention. If you don’t actively listen for your signals, you won’t hear them. What’s more, the whispers are usually telling you to take a risk. So it’s easier to ignore them. Quick tip: Carve out 15 minutes a week to answer this question – what should I be doing more of? We tend to answer this question with what makes us feel alive. Within a month you’ll see patterns. Those patterns point to where you should be placing your bets.

You have to hear a whisper about fifty times before you take action. The lag between when we first hear a whisper and when we take action can be months or even years. While potentially frustrating, it’s an important gap. It keeps us from doing stupid things. If we followed every whisper, we’d go insane. Take this different path. Go out on this limb. Ignore this person’s advice. Push back here. Taking the right set of consistent actions takes time. Often the only reason we finally take action is because the whisper becomes so loud that it’s more painful to ignore it than it is to pursue it. Quick tip: Go easy on yourself. But don’t let yourself off the hook. You need to keep experimenting as you sense the signals.

The journey to aliveness becomes easier when you let go of “shoulds.” Many of us don’t realize how overwhelmed we are by shoulds. This is what I should be doing. This is how it should look. This is where I should be right now. He should be doing this. She should be doing that. They should be supporting me more. Shoulds weigh us down so much that they hamstring our creativity and energy. Let go of the shoulds. They rob you of precious time exploring what really matters to you. Fashion designer Coco Chanel said, “How many cares one loses when one decides not to be something but to be someone.” It’s a wise observation. Quick tip: Spend time with people outside of your regular spheres—people who energize you. See the world they see. These people are not encumbered by the same shoulds. They show you options you didn’t realize you had. Paradoxically, the more time you spend with people who are different from you, the better you understand yourself.

The struggle to feel alive is worth it. Pursuing what makes us feel alive often gets wrongly labeled as self-centered. It’s anything but. Think about the people who’ve inspired you the most. Are they self-centered? Rarely. Are they doing something that makes them feel alive? Almost always. Have they followed a beaten path to get there? Almost never. Would it be good to have more people in the world like them? You bet. Quick tip: Feeling alive is a noble pursuit. Keep exploring to better understand the circumstances in which you feel most alive. Your journey is one of the most important gifts you can give yourself.

Feeling alive is at the heart of great leadership and great companies. A leader’s energy matters. The leader who feels alive is infectious. Unfortunately, so is the leader who doesn’t. You can’t fake genuine energy. You can’t wrap a bunch of best practices around an uninspired leader and hope to produce inspired results. With no countervailing energy to push it back, mediocrity eventually sets in and spreads. When leaders don’t feel alive, followers don’t either. Teams don’t feel alive. The culture doesn’t feel alive. Products and services are uninspired. Ultimately work doesn’t feel meaningful.

And isn’t that what we all really want—meaningful work? Work doesn’t have to be easy. And it doesn’t have to be interesting all the time. But it does have to feel meaningful in the long run—like we’re doing something that matters, that will make a positive difference, and that brings us and others to life.

If you aren’t doing that, what are you doing?

The post What Makes You Come Alive? appeared first on The Sundheim Group.

Leadership and The Art of Decision Making (Workshop)

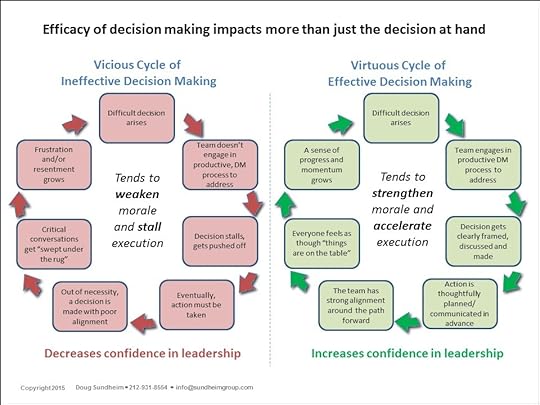

One of the biggest determinants of success for any leader or leadership team is efficacy decision making. When leaders are good at it, it drives momentum and growth. When they’re bad at it, mucks up all sorts of critical success drivers in an organization (see diagram below).

Please join me June 30 at the Norwalk Inn for a free workshop on Leadership and The Art of Decisions Making.

Content I’ll cover:

Common contributors to poor decision making

A framework for effective leadership decisions making

Mindsets that underlie effective decision making

A decisions making checklist to help you dynamically assess how effective your decision making is

Logistics & Details

June 30, 2015 at Norwalk Inn, Norwalk, CT

7:30-9:00am

Cost – $0

Limited to 30 people. Reserve early if you’d like to attend

To reserve a spot, RSVP by email to Mark Anderson at Execunet – Mark.Anderson@execunet.com. Please include your title and company name in your reply.

The post Leadership and The Art of Decision Making (Workshop) appeared first on The Sundheim Group.

June 8, 2015

“Best Practices” Are Often Fool’s Gold

It’s hard to attend a business meeting these days without the term “best practices” being bandied about. Best practices in social media. Best practices in cyber security. Best practices in performance management. If it’s a hot topic, chances are someone has figured out the current “best” way to do it.

On the surface it’s hard to disagree with the idea of best practices. Pre-packaged answers to the struggles you’re facing. Very alluring.

The trouble is the package is never really right for anyone but the people who packaged it. They had a different set of issues that drove their choices. Or they had a different set of professionals who could implement them. Or they had different goals. Or different risks. Or a different level of commitment.

And these differences rarely make it clearly into the description of best practices. Largely because the people who package them are concerned about their organization, not yours. And it’s just really hard to identify the full context in which the practices will and won’t work.

Take best practices for what they are. Helpful guidance, never clear answers. You still have to do the hard work to define the best practices for your organization

The post “Best Practices” Are Often Fool’s Gold appeared first on The Sundheim Group.

June 1, 2015

Successful Innovators Don’t Care About Innovating

Successful innovators care about solving interesting and important problems — innovation is merely a byproduct. If this distinction seems like hair-splitting, it isn’t. The two focuses create vastly different realities.

Focusing on innovating — as a worthy goal unto itself — tends to be born from self-centered motives: We need to protect ourselves from competitive forces. We need to ensure we have a growth engine. We need to keep up with other companies. To do all these things, we need to innovate. This is often a CYA perspective coming from an executive suite looking to protect its turf. It isn’t inherently bad. It’s just that this focus tends to create a culture where customers are on the sidelines, not in the center of the dialogue.

By contrast, focusing on solving interesting and important problems tends to be born from customer-centered motives: What’s going on with this set of customers? Where are they ecstatic? Where are they upset? Where do they feel good? Where do they hurt? How can we better serve them? These types of questions pull customer problems front-and-center and create a culture where that’s expected. And since people naturally want to solve problems, it pulls for innovation.

To illustrate, consider paint maker Sherwin-Williams, a company that has long been obsessed with solving painting contractors’ problems.

Twenty-five years ago while doing customer research, Sherwin-Williams uncovered an important insight: Contractors tend to make paint-buying decisions based more on proximity to job site than brand of paint. To them, time is money. This led to a hypothesis that saturating a market with stores to ensure there’s a store close to any job site will produce outsized market share growth. This was a new and innovative idea in a pre-Starbucks-on-every-corner world. Sherwin-Williams tested the hypothesis in four markets and it worked. But as they tried to roll it out to more markets, competitors quickly caught on. Suddenly it became a race for real estate and competitive advantage was lost.

Fast forward 20 years. During the 2009 recession, Sherwin-Williams’s competitors started shuttering stores in order to cut costs. Despite strong shareholder pushback, Sherwin-Williams did the opposite, opening 60–100 stores per year during the downturn. It was a risky bet, but they didn’t want to miss the opportunity to be close to customers when the market inevitably rebounded. When it did rebound, revenue growth far outstripped that of competitors. Sherwin-Williams’s stock price has quadrupled in the past five years.

So what’s the takeaway? Market saturation was an important distribution innovation, but it wasn’t what drove success for Sherwin-Williams. Success came from an unrelenting focus on solving contractor problems. That focus generated the initial innovation, but more importantly it generated the conviction to stick with the innovation when the going got tough.

When I asked Bob Wells, the Sherwin Williams SVP who shared this story with me, what he felt has driven the company’s success over the years, the word “innovation” never came up. But the word “customer” did — a lot.

“We’ve always looked at business more like dating than war,” Wells noted. “It’s a theme that runs through our 140-year company history. In war, you’re focused on beating the competition. In dating you’re focused on strengthening a relationship. That difference of perspective has a million knock-on effects for how decisions get made.”

Wells’s comment points to a truth so often missed in today’s let’s-get-some-innovation-in-here-quickly climate. Successful innovation is a mindset before it’s a process or outcome. It’s characterized by a dogged determination to see the world through your customers’ eyes. That mindset drives all the little details and decisions that can’t be captured in a process.

So how can you foster this mindset if it’s not already present in your organization? The simple answer is you just start doing it, even if you’re the only one. Disabuse yourself of the notion that innovation is some high-minded creative process reserved for a certain class of people. Remember that most great innovations have been developed by regular people inspired by a problem.

Get out of the building and talk to your customers. Listen to their challenges. Come up with back-of-the-envelope, harebrained ideas about how you can help them. Get comfortable with the idea that you’ll throw 99% of those envelopes in the trash. When you lose your motivation, go back to the problem statement. Never stray from the problem statement. Let it inspire you. Let it lead you. Also, stay mindful that problem statements shift and move. Never stray too far from your customers either.

Before long you’ll embody a customer-centered, problem-focused mindset. You’ll inspire others to start embodying it too. That’s the only way innovation ever really happens. Before all the fancy processes, there’s always a few people with a fire in their belly put there by a problem they can’t help but solve.

By Doug Sundheim

Follow the discussion on this article at HBR

The post Successful Innovators Don’t Care About Innovating appeared first on The Sundheim Group.

May 12, 2014

The Trouble with Leadership Theories

Several years ago a client of mine, Rob, fell in love with Jim Collins’s book Good to Great. Within a month he had given copies to everyone on his team. Soon after, language from the book made its way into Rob’s everyday speech.

One idea he especially loved was Level-5 leadership. “If we want to be great,” Rob would say, “we need more Level-5 leadership.”

I quickly grew tired of hearing him say it. His references to it were too vague and preachy. I could tell that his team was growing tired of it too.

Eventually, I asked Rob what Level-5 leadership meant to him. And more importantly, what it looked like in his organization. Not in a sound bite, but in his own words.

His answer:

We need a vision of this company for the next 10 years. We’ve spent too much time resting on our successes from the past 10. Either we come together as a team to figure it out or we’re going to drift into oblivion.

We have to be focused on building something bigger than our own bank accounts. We’ve lost sight of a broader purpose.

Our success has to start with our people. We have to inspire them to want to build something great alongside us. We have to be crystal clear about what the vision looks like in action. Then we have to walk the talk ourselves.

Rob’s answer wasn’t really what Collins meant by Level-5 leadership. Yet it was powerful in its own right. I could understand where Rob stood and what he believed. The power, of course, didn’t come from just his words; it came from his strong connection to them. That connection was missing when he tried to use Level-5 leadership as shorthand for his own thinking.

To be clear, Good to Great is filled with excellent research and insights. And leadership theory has its place. Theories pull disparate ideas and data into working models, distinguishing concepts and providing a systemic perspective.

But the trouble with leadership theories is they’re easy to hide behind (often inaccurately). They become proxies for actual leadership. When something important is on the line, people don’t follow five-tiered triangles, four-box matrices, or three concentric circles. They follow real people.

I advise clients to capture theories of leadership in their own words. Merge book smarts with street smarts. Avoid using jargon and vague concepts. Make it visceral and real. Keep it brief; write it on a single sheet of paper.

A year ago, a client asked to see my one-sheet theory of leadership. I hadn’t done the exercise in a decade. That night I revisited my theory and rewrote it. In fifteen minutes and six brief lines I captured my current thinking about great leadership, exactly as it came to me. Here’s what came out:

I believe:

There’s too much noise in business today. There are too many things vying for our attention. Senior leaders must be diligent about cutting out the noise to get their organizations focused on what really matters.

Playing it safe is dangerous. You never maintain the status quo by playing it safe. You get worse. You lose your edge. You lose your confidence. You don’t feel alive. You can’t win.

Mediocrity is cancerous. Once you begin to accept mediocrity, it sends signals that it’s acceptable. Before long everyone and everything around you is mediocre.

Unless you’re relentlessly open and honest in your communication—constantly—things fall apart. I believe that close to 100% of all business problems can be traced back to poor communication at some point.

People want to do great things. They want to build great things. They want to be involved with other great people. Great leaders create the conditions for other people’s greatness to come out.

You need to hold people’s feet to the fire. Do it with compassion. Do it with love. Do it with respect. But don’t let people off the hook. This is where mediocrity starts.

I was surprised at how good it felt to write these statements. It felt better than I remember from my previous versions. When I shared the statements with clients, there was strong resonance. Two people actually posted them at their desk. I wondered why; after all, the content wasn’t topically new.

A colleague shared her take. “The statements are powerful because they’re not polished. They’re just what you believe. You’re not trying to encapsulate hundreds of data points into a grand, catchy theory. You’re not trying to be politically correct and perfect.”

I think she’s right. People are tired of the leadership buzzwords and models that feel too tidy, analytical, and removed. A client recently told me his executives are suffering from “framework fatigue.” I understand; I think we all are. The language of leadership has become so cookie-cutter and cliché that we filter it out.

Of course, the act of great leadership is never cliché. It’s an art. It should be informed by smart research, yet it should be shaped by on-the-ground experience. Both are critical. By all means read the theories, attend seminars, and talk to luminaries. They provide a solid foundation. But then ask yourself, what do I believe makes a great leader? Trust your gut and experience. Don’t worry about making it perfect. Worry about making it a reflection of what you truly have found to work. Your theory might not have all the spit and polish of formal leadership theories, but it just might be what takes you and your organization from good to great.

Follow the discussion on this article at HBR

The post The Trouble with Leadership Theories appeared first on The Sundheim Group.

January 13, 2014

What’s Your $1 Billion Idea?

Anyone would be inspired by the story of Nick Woodman, the CEO of GoPro, a $2.5B company that makes wearable HD video cameras. The highlights:

In the late 1990’s/early 2000’s, Woodman blows $4M of VC money on a failed venture called funBugs.com, an ultimately ill-conceived loyalty, sweepstakes, and entertainment website. In 2002, unsure of what to do with his life, he takes off to surf in Indonesia and Australia. He wants to capture live-action shots from his surfboard. The only cost-effective way to do this is by strapping a disposable camera to his wrist with rubber bands. Not surprisingly, it doesn’t work well.

Back in the US, unable to find a suitable camera wrist strap, Woodman sets out to develop one himself. He quickly realizes it would make a better product to include the camera too. Meanwhile, he has no knowledge of cameras. It takes him two years to find and prototype the right camera. He bankrolls his efforts by selling shell necklaces and getting a small loan from his mother. The first camera comes out in 2004. He sells it door-to-door to surf shops. It’s a hit. He then develops a video camera that debuts in 2007. It’s also a hit. In the years that follow, he develops increasingly cool yet affordable cameras with pro-like, wide-angle HD video. By 2013, GoPro, with a mission to “capture life’s most exciting moments,” has the best-selling camera in the world and around $1 billion in yearly sales.

I love Woodman’s story. Beyond its obvious compelling arc, it reminds me of how important it is to live the questions right in front of us—and not waste time looking for big ideas “out there” somewhere else. The questions that annoy, frustrate, or bother us are our greatest opportunities. They poke us and get under our skin. We’re naturally motivated to solve them.

To live a question is to commit to it—to explore it even though we’re not sure where it will take us. We explore it because it’s interesting, meaningful, challenging, and often fun. We also explore it because we know that even if we fail, something good will come from it. We’ll learn something important. Or at least have a great story to tell.

Of course, to get better at living interesting and meaningful questions, we have to get better at identifying them. Inspired by Woodman’s story, I decided to exercise this muscle. Over the course of one day I jotted down all the potentially interesting questions that occurred to me. I didn’t judge or censor them, I just captured them. Here’s my list:

Why are children’s car seats so tough to install?

Why do so many consulting firms underwhelm their clients?

Why has that beautiful building on such a desirable corner been abandoned for so long?

What’s really going on with the massive vacant waterfront in my town?

What’s the connection between poetry and great leadership?

How come every time I write marketing copy, it sounds boring when I look at it the next day?

Why can’t I find a stylish, warm, winter coat without a hood?

How can I find more time to read?

It’s not an earth-shattering list, just simple seeds of ideas. That said, the exercise turned out to be far more insightful than I had anticipated.

First, I didn’t realize how many questions cross my mind each day. I was micro-brainstorming all day—and probably have been my whole life. I’d just never noticed before. Second, the process changed how I saw the questions. The mere act of writing them down reframed them from random thoughts into potential opportunities. It pulled me out of a problem orientation and put me into a solution orientation, which is a more powerful way to live.

For example, I didn’t have to just complain about car seats; I could explore mechanisms for making them easier to install. There might be good reasons why the process is such a pain in the neck. But then again, there might not be. After all, before Woodman developed a wearable camera, there wasn’t a good reason why that didn’t exist yet.

We tend to think that the problems we see are so obvious that people smarter than us must already be working them—so why waste our time thinking about them? But often that isn’t the case. There are countless reasons why seemingly obvious problems go unsolved. One of the biggest reasons is that people best positioned to solve them often have vested interests in not solving them.

Perhaps above all these questions is a larger one—how do we choose which questions to pursue? If I wrote eight questions a day, that would be close to 3,000 a year. You can’t do anything with 3,000 questions. But here’s my hunch: patterns in our questions show up over time. We keep wondering about the same or similar things over and over. And those patterns are gold because they point to our motivation—and quite possibly, our next great exploration.

So here’s my plan. Over the next year I’m going to take 10 minutes per week to write down the interesting questions that cross my mind. At the end of the year, I’ll review the 52 lists for patterns and themes. And by January 2015, I’ll see where I end up. Maybe I’ll have something worth working on.

Follow the discussion on this article at HBR

The post What’s Your $1 Billion Idea? appeared first on The Sundheim Group.

October 22, 2013

The Hidden Dangers of Playing It Safe

Last year Dina, a CEO I’d been working with, felt that leaders on her team were playing it too safe. They weren’t finding and pursuing new growth opportunities and it was crippling the organization. She kicked off her October management team meeting, which I was attending, by reading the following passage from my book:

The dangers of taking too much risk are very clear. We’re reminded of them in the news every day. Businesses, families, and individuals are ruined in shocking fashion—“150-year-old bank and pillar of Wall Street is gone in the blink of an eye”; “Major oil company loses $90 billion in market value in three months”; “Kite surfer tries his luck in a hurricane and slams into a building.” Astounding lapses in judgment are everywhere. The warnings of overambitious risks are clear—watch yourself and don’t do anything stupid.

Unfortunately, we rarely hear any warnings about playing it safe.

We don’t see news headlines that say, “Low-risk approach forces local business to file for bankruptcy,” or, “Stunningly conservative move pushes global pharmaceutical company to the brink of failure,” or “Man retires after a mediocre career and feels painful remorse for never having laid anything on the line.”

The dangers of playing it safe aren’t sudden, obvious, and dramatic. They don’t make headlines. They develop slowly over time and are almost impossible to pinpoint. This fact often makes them more dangerous than the high-profile missteps we see and hear about in the news because, like a slow leak in a tire, you don’t see or feel these dangers on a daily basis. You become aware of them only when you realize that you’re stuck and you’re not really sure how it happened.

The dangers of playing it safe are hidden, silent killers.

When she was done reading the passage, she looked up and asked the group:

“If a journalist observed our organization for a few months, what headline would she write?”

It was a great question. I was familiar with the challenges the organization was facing and was eager to hear the answers. After a few tepid responses, Walter, the CFO, threw out a grenade headline: Company tries desperately to hang on to aging cash cows and antiquated ways of doing business in the flawed hope that they can maintain the status quo forever.

I loved it. At first the team didn’t know what to do with it. There was a collective “did-he-just-say-that!?” look on everyone’s face. It was quickly followed by several attempts to caveat and soften his headline. Rashid, the COO, commented, “Sure we’re struggling, but that’s just the market, we’ll bounce back.” Walter stood his ground against the status-quo onslaught. People got uncomfortable. A heated conversation ensued about just how antiquated and “in jeopardy” the cash cows really were. Then the discussion died down with no clear resolution.

I was frustrated. I didn’t think the meeting was very productive. I felt that Walter had just given the management team a well-deserved kick in the pants—and they summarily dismissed it without letting it sink in.

Three months later I realized my assessment had been wrong.

By the January meeting, Rashid had a different attitude. Armed with negative customer feedback he had collected because of Walter’s comments in October, he too had concerns about the organization’s growth prospects. He felt they were falling into a false sense of security. Walter’s headline had stuck with Rashid, irritating him and motivating him to understand the issues better—just what the headline was supposed to do. Rashid was beginning to see what Walter was seeing.

The October and January meetings became a tipping point in jarring people out of their comfort zones, forcing them to realize they had to make some tough strategic decisions. In the ten months since those two meetings there’s been a marked improvement in the focus and energy of the management team and broader organization.

Watching this unfold, one of the lessons I re-learned (for about the 68th time in my career) is that change works in mysterious ways. If you had asked me a year ago if Walter would be the one to throw out the initial grenade, I would have bet against it. And if you’d asked me if Rashid would be the tipping point to change, I would have also bet against that. But there they both were, leading the charge.

However, I think the bigger lesson here is one of context. What context motivated Walter and Rashid to do what they did?—to push, to question, to challenge the status quo, to see the dangers of playing it safe for what they are, and to move towards deeper understanding and action. Neither of them had a history of this behavior. What changed?

It was the culture that Dina had created over the past year: Question everything.

What does this business look like in five years? What are our customers worrying about today? What will they be worrying about tomorrow? What are our employees seeing but not saying? Where are we communicating effectively? Where are we failing to communicate? What strengths aren’t we capitalizing on? What opportunities are we letting slip through our fingers? How would we try to beat ourselves if we were our competitors? What weaknesses would we exploit? And where are we settling for “good” when we should really be going for “great?”

Over the past year Dina had been asking these questions incessantly and demanding others do the same. She’d been pushing people to make themselves uncomfortable in searching for answers. In some instances she’d move the organization towards action. In others she’d just leave the questions hanging, letting people sit with the Socratic discomfort for a while. In all situations she made it clear—if you’re not critically reflecting on what you’re doing, you don’t know what you’re doing. The world is moving too fast.

Ultimately, Dina realized a fundamental truth about playing it safe that we should all keep in mind—while it’s dangerous in the long term, it just feels better in the short term. And so people naturally gravitate towards playing it safe. Moreover, playing it safe has a below-the-radar, how-bad-could-it-really-be quality which creates an insidious dynamic that’s tough to penetrate.

Dina’s solution to breaking through the tendency to play it safe was simple; attack it every day in the organization. Bombard it with tough and thoughtful questions. Hold other people accountable for doing the same. Then hold them accountable for strategizing and executing. In essence, make it more uncomfortable to play it safe than to think critically and take risks.

Follow the discussion on this article at HBR.org >>

The post The Hidden Dangers of Playing It Safe appeared first on The Sundheim Group.

October 16, 2013

I’m Angry and Embarrassed by the US Government’s Behavior

August 22, 2013

Closing the Chasm Between Strategy and Execution

Setting strategy is elegant. It’s a clean and sophisticated process of collecting and analyzing data, generating insights, and identifying smart paths forward. Done at arm’s length in an academic fashion, tight logic is the only glue needed to hold ideas together. The output is a smooth narrative in a professional-looking document made up of Venn diagrams, 2×2 matrices, and high-level plans of attack. Jettison this business. Focus efforts here. Build up this organizational capability.Executives buy into the plan. The strategists, confident in their intellectual prowess, quietly recede into the background.

Then the trouble starts. Execution is a minefield. The clean and elegant logic of strategy gets dirty in the real world. Agendas compete. Priorities clash. Decisions stall. Communication breaks down. Timelines get blown. It’s never a question of if these problems will happen; it’s a question of when and to what degree. Managing these challenges takes street smarts and muscle. Overwhelming success means you take a few punches, but still make the plan happen. The process is always a little ugly. The executors’ dirt-in-the-fingernails view on the ground is much different from the strategists’ high-minded view from the air.

The implication is obvious — strategists and executors must work together better to bridge these two worlds. It’s common sense. Unfortunately, it’s far from common practice. What typically happens is an awkward hand-off between the two. In the worst cases the strategists adopt an elitist, disconnected mindset: We’re the idea people, someone else will make it happen. They don’t bother to truly understand what it takes to implement the ideas. They don’t engage the executors early and ask, “How will this actually work?” The executors contribute to the trouble as well. Often they don’t truly understand the thinking behind the strategy. They take it at face value and don’t ask enough tough questions.

When things fall apart, each points a finger at the other side.

The easy solutions for this divide are the process solutions: better project management, clearer rules of engagement, and tighter operating policies. The tougher (and more powerful) solutions are the cultural solutions: getting each side to actually care about what the other side is doing. Not just from a lip-service perspective, but from a fundamental-belief-that-my-success-is-inextricably-tied-to-your-success-so-I-better-engage-with-you perspective.

Strategy and execution is a false dichotomy, unnaturally sheared apart in order to divide labor in increasingly complex organizations. It’s an efficient approach. Alone, the shearing isn’t a problem. The problem is that both sides don’t see it as their responsibility to intelligently pull the two sides back together again. They leave a chasm, hoping that it will miraculously close on its own. It never does. Things just fall through it.

The best strategists and executors don’t see a hand-off between strategy and execution. They see an integrated whole. They continuously hand ideas back and forth throughout all phases of a project, strengthening them together. They fight to bring each other closer. Over the years, I’ve noticed that the best strategists and executors believe certain things that drive their success — things that the mediocre strategists and executors don’t believe.

The best strategists believe:

If I can’t see and articulate how we’re actually going to make this strategy work, it probably won’t work. Smart strategists know that there are a lot of gaps, holes, and challenges in their strategies. They tirelessly keep a critical eye on the viability of their plans and stay curious — continuously asking themselves and others, how will this really work? When they find issues, they team up with the executors and get out in front of them.

While it’s painful to integrate execution planning into my strategizing, it’s even more painful to watch my strategies fail. Most strategists dislike execution planning. It’s a tedious process for someone who likes to think about big ideas. But good strategists understand that they have unique insights into the strategy that executors will miss, usually to disastrous ends. So they stay engaged.

Sounding smart is overrated. Doing smart is where the real value lies. Effective strategists aren’t full of themselves. They realize their ideas are just that — ideas. They know that if they’re not executed well, their strategies are nothing more than daydreams.

I’m just as responsible for strong execution as the executor is. Is this actually true? Likely not. But it’s a powerful mindset to hold. The best strategists see themselves as leaders, not merely thinkers. They feel their job is to deliver results, not just ideas.

The best executors believe:

I need to be involved in the strategy process early — even if that means I have to artfully push my way into it. It’d be easy if executors naturally had a seat at the strategy table. Unfortunately, they often don’t. Many still receive strategies as a hand-off. Smart executors don’t take this sitting down. They figure out how to get into the strategy process early.

I need to be perceived as relevant and valuable to the strategy process. Smart executors know that they must earn a seat at the strategy table by actually adding value. They must move things forward by providing relevant and thoughtful considerations that strengthen the strategy. They can’t show up and “just listen” in strategy meetings or else they won’t be invited back.

I need to know the “whys” behind the strategy. Smart executors want to know the intent behind the strategy. They want to know the thinking that drove certain choices. They know that this knowledge is crucial to making tough judgment calls when circumstances change down the implementation road (as they inevitably do).

I’m just as responsible for strong strategy as the strategist is. Again, is this actually true? Probably not. But that’s irrelevant. The best executors see themselves as leaders, not merely implementers. They feel their job is to deliver strategic advantage for the organization, not just a project.

You can see a clear thread of responsibility running throughout all the beliefs above. Not responsibility for a given task, but rather responsibility for the not-given tasks — the messy spots in the middle where it’s not clear who should own something. The best strategists, executors, and leaders stand up and say, “I’m responsible for it” even if it isn’t in their job description. It’s doubly powerful when both strategists and executors do this, meeting in the middle. That’s true collaborative leadership. When these spots go unwatched, un-owned, and unaddressed, they bring down projects and eventually whole companies.

Follow the discussion on this article at HBR.org >>

The post Closing the Chasm Between Strategy and Execution appeared first on The Sundheim Group.

August 15, 2013

Good Leaders Get Emotional

Much of what comes out of people’s mouths in business these days is sugar-coated, couched, and polished. The messages are manufactured, trying to strike just the right tone. Genuine emotion stands in stark contrast. It’s a real person sharing a real feeling. When we hear it, we’re riveted — for one because it’s rare, but also because it’s real. Sometimes it’s uncomfortable and a little messy. But that’s what makes it powerful. No one is trying to hide anything.

We hide emotions in an attempt to stay in control, look strong, and keep things at arm’s length. But in reality, doing so diminishes our control and weakens our capacity to lead — because it hamstrings us. We end up not saying what we mean or meaning what we say. We beat around the bush. And that never connects, compels, or communicates powerfully.

Yes, being too emotional in business can create problems. It clouds objective analysis, screws up negotiations, and leads to rash decisions. But in nearly two decades of working with leaders, I’ve found that showing too much emotion is far less of a problem than the opposite — showing too little.

Emotions are critical to everything a leader must do: build trust, strengthen relationships, set a vision, focus energy, get people moving, make tradeoffs, make tough decisions, and learn from failure. Without genuine emotion these things always fall flat and stall. You need emotion on the front end to inform prioritization. You need it on the back end to motivate and inspire.

Over the last 17 years working with senior teams I’ve collected a lot of examples of leaders getting emotional — to good end. Here are a few:

“I’m angry that I had to spend 3 hours dealing with a problem that you created — a problem that you should have handled. Don’t put me in that position again.” Joan, a partner in a consulting firm hated conflict and rarely said things like this. She normally just rolled up her sleeves and took care of problems herself, even if she hadn’t created them. Then she got promoted to the head of the Southeast Region. There were too many problems to take care of by herself. Her outburst above and the ensuing conversation was a survival tactic, but it sent a clear message to the partner in charge of the Atlanta office. Don’t let this employee staffing issue happen again, and if it does, fix it yourself — before it lands on my plate. It was uncharacteristically aggressive for Joan, but exactly what the situation needed. That was two years ago and the problem hasn’t happened since.

“I think most of the ideas on this list are sh**ty…but that one’s great. Let’s do it.” Jamie, the CEO at a biotech company had a reputation for walking the fine line between galvanizing a team and offending them. He shot straight and went with his gut. While he had to clean up messes from time to time, it was never anything egregious. And his approach had a profoundly positive impact on the organization. Everyone knew where they stood with him. And everyone knew that he meant what he said. When he got excited about something, no matter what, he was going to make it happen. His energy and emotion accelerated innovation and execution across the company.

“I’m upset. I’m responsible. I apologize.” It was the type of mea culpa no one expected from Jeremy. The COO of a software firm, he had had a horrible relationship for years with Ron, a key product development VP. Finally, frustrated and tired, Ron quit. Within months it became clear that Jeremy had underestimated Ron’s impact on his team. It started to fall apart. With Ron gone, Jeremy was able to step back and see that he’d let a small issue create a huge problem. And that his stubbornness was at the root of it. He apologized to the executive team with a tear in his eye. I was there. It was shocking. That’s not the kind of guy Jeremy was. In an instant I understood how much he cared about the company and how ashamed he felt. Everyone saw it. Amazingly, he ended up apologizing to Ron and hiring him back.

Often, one of the reasons we don’t show emotion is because we’re not even aware we’re feeling it. We’re angry, frustrated, or upset and we suppress it. We’re excited, motivated, or inspired and we temper it. We do it without even realizing it. Emotional data seems less relevant in the business world where logical data reigns supreme. But it’s not only relevant, It’s usually the lynchpin to change and growth.

One further point. It’s important to note there’s a gender bias around showing emotion at work. I’ve seen that in the same places where men get labeled tough, passionate, or open, women get labeled bitchy, hysterical, or weak. I find this double standard particularly destructive and insidious because it leads to women’s emotions getting dismissed more readily than men’s, often at exactly the times where that emotion is most needed — times when no one else in the room is raising the most important points. We all need to stay aware of this double standard and not enable it.

My advice to all leaders is to pay attention to your emotions. At least a couple times a week, stop for 10 minutes and ask yourself, “What am I feeling right now?” Write it down if you can. Keeping a regular journal is a helpful way to understand how you’re feeling.

Then pick your spots to let loose a little. Let your emotions out. Let people in. Both are critical to effective leadership.

Follow the discussion on this article at HBR.org >>

The post Good Leaders Get Emotional appeared first on The Sundheim Group.