Doug Sundheim's Blog, page 4

June 20, 2016

Should you really build leadership at every level of your org?

[Spoiler alert: Yes!! If you don’t you’re dead in this economy.]

I debated this question with the COO of medium-sized technology firm recently.

His take was that while leadership at every level sounded nice, in reality it was impractical and unwise. His argument surrounded five reasons:

Some people don’t have the skills to lead

Some people don’t want to lead

If everyone thinks they’re a leader too many people are directing things and not enough people are doing things

Having too many leaders creates confusion

Developing leaders is a resource-intensive task and, given reasons 1-4, not a good investment except for high potentials

I understand his logic, but it has a flaw; it defines leadership too narrowly.

Too often we cleave to an antiquated notion of leadership as visionary direction-setting and fearlessly leading the troops into future with a few big strategic decisions. Yes, that is one type of leadership, but it’s grounded in a set of assumptions about how the world works (military-industrial and command-and-control) that are rapidly changing. When the world moved more slowly a few big decisions at the top could legitimately set a trajectory for years to come. In this day and age, that’s a recipe for obsolescence.

Here’s a broader and more useful definition of leadership nowadays: critical and collaborative thinking and action given what you see in front you.

You want your C-Suite doing this, but you also want the lowest-level person in your organization doing it too. The scope and impact of their decisions will obviously differ, but the general mindset remains the same—we need everyone motivated to solve problems. Building critical and collaborative thinkers and doers at one level strengthens their ability to do the same at the next level and the next level.

Here’s a practical idea. Define what leadership looks like, as a mindset and set of behaviors, at every level of your organization. Create a curriculum that builds on itself as employees grow. First it’s about leading the self, then leading others, then leading the org. At each level touch upon the other levels so people see the bigger picture of leadership in the org. Have people understand what’s going to be required of them before they get there. The smart ones will start picking it up themselves.

Don’t wait to teach leadership until people are “ready” and somehow “worthy of investment.” If you do, you’ll never end up with who you need when you need them. Invest smartly in leadership building and a leadership culture all along the way. It’s the foundation of competitive advantage these days.

The post Should you really build leadership at every level of your org? appeared first on The Sundheim Group.

March 29, 2016

The Risk of Not Risking

Risk taking is about creating new things, understanding what you’re made of, and feeling confident and alive. You lose these when you play it safe for too long, in essence losing the “life” in life. So you need to take risks. But even when you know that you need to take risks, fear can still stop you from doing it. It’s only by being aware of what’s at stake when you do not take risks—loss of growth, progress, and learning—that you find the motivation to risk.

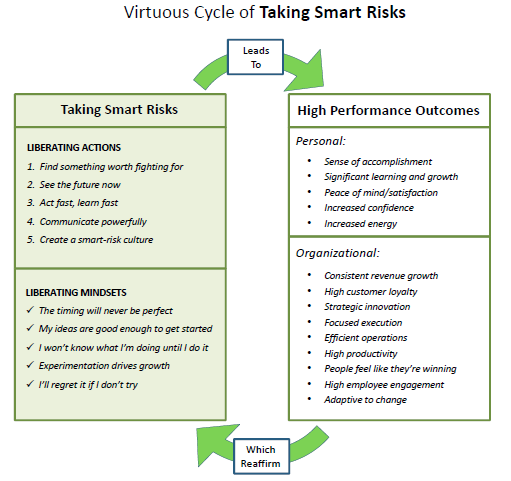

Smart risk taking starts by having a balanced focus on both the costs and benefits of risk taking. Too much focus on the costs leads to paralysis. Too much focus on the benefits leads to peril. Keeping both in mind puts you in the smart-risk zone. There, liberating mindsets increase your confidence to take risks. In turn, these mindsets lead to liberating actions. Over time, the mindsets and actions strengthen each other, producing high performance outcomes at both individual and organizational levels. I call this the virtuous cycle of taking smart risks (see Figure 1). With every smart risk comes more learning, more confidence, and better results.

Figure 1

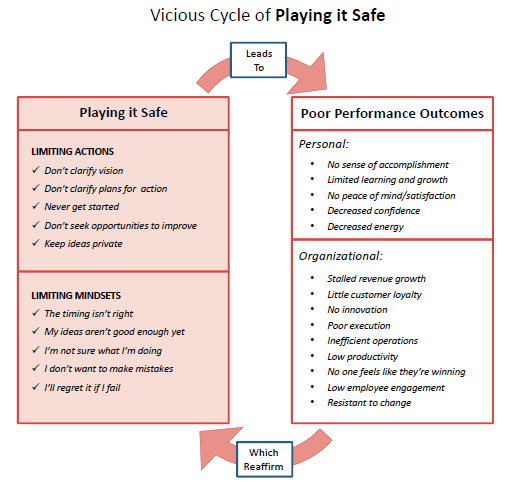

But you can only produce positive outcomes if you continue to take risks. If you idle in “neutral” too long, you end up in a different cycle, the vicious cycle of playing it safe (see Figure 2). Here you produce increasingly poor performance outcomes until you get stuck in a rut.

Figure 2

I share these two risk cycles to point out that there’s no third option. There is no place where you can just stop risking and have everything remain in the status quo. Once you stop risking, you quickly stop growing. You stop producing results. You stop feeling alive.

Risk taking is a set of skills that can be learned, practiced, and sharpened

While there’s always a degree of art to taking risks—and some people are more naturally skilled at it than others—everyone can improve, finding smart ways to push outside his/her comfort zone. In my book Taking Smart Risks, I cover the process of smart risk taking with relevant stories and tools. As I researched the book, the same five themes kept popping up in everyone’s stories—from improve comedians to senior executives. Here they are with brief suggestions for action.

1. Find Something Worth Fighting For (SWFF)

Carve time out of your schedule to stop and think about what you’re willing to fight for. You must plan for it proactively because it is nearly impossible to do this type of thinking in the course of your normal daily routine. If it’s helpful, do it with other people.

Find a SWFF that’s challenging, something that you can and want to be good at, and something that makes a positive contribution. This ensures that the SWFF will have staying power and be truly motivating.

If you’re clarifying a SWFF for your organization, ensure that it stirs emotion and inspires action. It should not feel like wordsmithed corporate-speak. It should feel like something that everyone cares deeply about. It’s helpful to engage a broad cross section of people for input to the SWFF.

2. See the Future Now

Trust your instincts. The things you see and feel all around you are the most important data you can collect on the future. Never discount your own perspective. There’s a good chance that you’re the only one seeing things from your particular vantage point.

Conversely, don’t trust only your perspective. Get out of the office and spend time with other people, especially customers. Pieces of the future are strewn everywhere, and the more you explore, the more you will find.

Make decisions. Give yourself time, but don’t draw things out too long. Review data, talk things over with others, predict your fail points, and then decide on a course of action. Deciding builds energy on a team. Not deciding saps it.

3. Act Fast, Learn Fast

Start before you know where to start. In the beginning of any endeavor, things are never very clear. Remember that the first hurdle is often the hardest, and that the actions needed to get out of the gate are often smaller than you realize.

Fail fast, cheap, and small. Continually test hypotheses about what it will take to succeed. Learn from what you find, and then do more tests. Remember that the absence of failure isn’t a positive sign. It’s a sign that you’re not taking enough chances.

Learn from everything. Remember that you’re at your weakest when you think you know all the answers. Make team learning opportunities (such as debriefings) simple and structured so that you can harvest helpful lessons quickly.

4. Communicate Powerfully

Assume that your communication is bad. Even if it’s good, assume that it will be bad soon. This is because no matter how effective we are at communicating, we all fall victim to the communication blind spot at times—thinking that something is clear to everyone else just because it’s clear to us.

Put regular communication structures in place to stay aligned during risk taking. Don’t rely solely on ad hoc meetings or random conversations, which tend not to happen often enough to manage risks effectively.

Have tough conversations when they come up. Make it an expectation that those around you will do the same. Doing so decreases risk in already risky situations and increases trust.

5. Create a Smart-Risk Culture

Define the behaviors and expectations that demonstrate a smart risk in your organization so that people are clear about whether or not they’re taking such risks—and if they’re not taking them, what they need to change.

Measure smart risks by a broader set of results than just project success. Measure learning generated and disseminated in the organization. Measure impact on future opportunities. Acknowledge smart failures that might have missed project goals but delivered value in other ways. Doing so sends a strong message about your commitment to risk taking.

Ask yourself, “What do I have to lose?”

As you consider the areas of your business or your life where you want to take more risks, ask yourself the proverbial question, “What do I have to lose?” More often than not, if you size up the risk honestly, you’ll find that you have more to lose by not taking it than by taking it.

In all the years I’ve been helping people push themselves and their organizations further, I’ve never once heard anyone say that he regretted taking a smart risk. When done intelligently, risk taking never leaves you empty-handed. Even in failure, the experience provides critical learning for the future.

The key is to start moving. Your path forward becomes clear once you’re walking on it, not before. The risk-taking journey always brings challenges, but it also brings the strength and skill to deal with them. It always feels difficult, but it also feels meaningful and rewarding. And in the end, the journey always brings the same two realizations. You didn’t have to be a hero to succeed; you just had to keep moving. And the greatest risk in life is never risking at all.

Excerpted and adapted from Taking Smart Risks

The post The Risk of Not Risking appeared first on The Sundheim Group.

March 16, 2016

Spend More Time With Your Customers

Sometimes the most powerful business advice is the simplest.

Businesspeople give a lot of excuses for not spending enough time with customers. Being too busy is the most common one I hear. Whenever an executive tells me that she’d love to spend more time with her customers, but she’s too busy, I ask to see her calendar for the coming month. Invariably, 50 to 70 percent of what’s scheduled could easily be considered lower priority than spending time with important customers. These people just aren’t carving out the time.

No one knows this better than customer experience expert and bestselling author Tom Connellan. One of the most powerful tools he uses with clients is the customer panel. He puts his client executives in a room with their largest customers so that the customers can give the executives feedback. He asks the customers to share the good, the bad, and the ugly—and not to pull any punches.

Having done hundreds of these panels, Connellan has noticed two overwhelming trends. One, the senior executives are always shocked and surprised by what they hear. Two, the shocking stuff is never good.

One of his best stories, that he recently recounted to me, is of a defense contractor who brought in a U.S. Navy admiral as one of its customers. Before the admiral even sat down, everyone could tell that he was in a foul mood. When it was his turn to speak, he launched right in, wasting no time with pleasantries.

“How many of you have ever been on one of my boats?” the admiral asked loudly and sternly.

None of the executives’ hands went up. The admiral surveyed the room for a few seconds and then remarked in a scolding tone, “I didn’t think so.”

Connellan could see the executives straightening up in their chairs.

“How many of you have ever been with any of my sailors?” the admiral followed up.

Again, none of the executives’ hands went up.

The admiral surveyed the room another time for effect, seemingly meeting the eyes of every single executive before saying, “I didn’t think so.”

“The U.S. Navy is one of your largest customers,” the admiral continued, “and yet none of you has ever been on one of my boats and none of you has ever spent any time with my sailors.”

For the next 10 minutes, the admiral went through a list of issues he had with the company. The headline was, the company was totally out of touch with the Navy’s needs. He made the point that one product in particular seemed to have been developed with absolutely zero knowledge of what a sailor does on a daily basis.

He finished by saying, “You’re so busy trying to sell me ‘stuff’ that you’ve forgotten that I have customers, and those are the men and women out in the fleet that are defending our country right now. If they’re happy, I’m happy. If they’re not happy, I’m not happy. You have to stop spending time schmoozing me and start spending time figuring out what they need.”

Connellan has so many stories like this that it’s scary. It’s an endemic problem throughout many organizations. Leaders at all levels don’t get out of the office and don’t have their eyes and ears on the street. Instead, they see the world through the hazy fog of their conference rooms and boardrooms. Layers of other people, who aren’t getting out of the office either, are advising them. It’s an organization-wide replication of the classic game of telephone. When it comes time to place bets on the future, these leaders are flying blind, totally out of touch with the nuances of what customers really want.

Taking the time to fill in those blind spots leads to decidedly smarter decisions.

Excerpted and adapted from Taking Smart Risks

The post Spend More Time With Your Customers appeared first on The Sundheim Group.

March 1, 2016

3 Reasons Your Strategy Meetings Irritate Your Team

Originally published on Harvard Business Review

Used well, strategy meetings provide clarity and momentum. They align a team around key decisions and create positive energy.

Used poorly, strategy meetings irritate people. They waste time and energy, or worse, strengthen entrenched points of view creating frustration and resignation.

In my work with companies from large Fortune 500 firms to small startups, I’ve attended hundreds of strategy meetings. I’ve seen leaders make three common mistakes over and over again:

(1) Drafting an overly ambitious agenda. Executive teams are often too optimistic about what they can accomplish in a short period of time. For example, one client allotted one hour at a 10-person meeting to gaining “a deeper understanding of the challenges we’re facing in Europe and laying out a high-level plan of attack on how to address them.” I looked at him and said, “You realize there’s no way that’s going to happen, right?” He ruefully agreed.

I know why he was doing it. He had four big topics on his mind and he wanted to get resolution on all of them in a six-hour meeting. When he reflected on it rationally, he knew that was impossible. He was just frustrated.

My suggestion is to prioritize your issues and pick one or two to address. Leave the others for a later date. If you do a great job moving through a limited set of issues, people will be less reluctant to have another six-hour meeting in the near future. In fact, they’ll likely welcome it — because they’ll expect to get something accomplished then too.

However, if you do a mediocre job running through too many issues, you’ll have screwed yourself on two levels: 1) you won’t have good resolution or buy-in on what you’ve discussed that day, and 2) people won’t be motivated and focused for the next meeting.

(2) Not doing enough meeting preparation. Most of the hard work of a good strategy meeting happens before the meeting. Doing research, gathering perspectives, teeing up scenarios, identifying important questions. Sometimes you have the time and resources to do a proper strategic work-up. Sometimes you have to rely more heavily on intuition. Either way, you should arrive at a clear point of view and document itbeforethe meeting. The meeting can be used to critique, debate, or expand a strategic point of view. But a strategic meeting should never be used to create a strategic point of view. It’s simply too hard to do this in real time with a lot of people.

Still, I see it happen all the time. Unprepared, teams casually wander into tough topics filled with land mines. They think they’ll “get everyone into a room and get on the same page.” Then they’re surprised when the meeting blows up or derails.

Keep in mind that there’s a good reason why you’re having a meeting rather than just making a decision on a given topic — it’s complex. If it wasn’t complex, you wouldn’t need a meeting. Complex topics need smart and focused prep work.

(3) Underestimating the need for skillful facilitation. Great facilitators are like jungle guides. They know their intended destination, the general contours of the landscape they’re traversing, the strengths and weakness of the people they’re guiding, and how to keep things moving when conflict erupts or conversation peters out. It’s part science, part art. But skilled facilitators are pretty rare. Instead, I see four common facilitator errors:

They never set clear objectives for a conversation. What does success look like for a given conversation? Do we want to provide input? Debate? Make a decision? Too often objectives are never clarified in advance. People just jump in and start firing off opinions with no apparent purpose other than to give a point of view. You arrive at the end of your allotted time no clearer than when you started. My advice: Be crystal clear about what you hope to get out of a conversation before you start it and get everyone aligned on the goals.

They pick the wrong discussion strategy. You might have the right topic and set of objectives you’re trying to reach, but the wrong discussion strategy. The most common faux pas is trying to get too many people talking about a complex issue at once. I’ve found 7–10 people is the max you want discussing a complex topic. More than that and people start to disengage, killing the energy of the conversation. If you have a bigger group, break them up and cull generated insights later.

They miss the signals in the noise. The most important signals in a strategy meeting don’t always jump out at you. They can get lost in a sea of noise. One common reason is that the loudest voice many not be the most astute. Good facilitators must quickly and dynamically separate signals from noise to ensure they’re focusing on what matters most. Before the meeting starts, have a clear opinion regarding the most important signals you think should come up. That way you have a better chance of spotting them.

They let the conversation meander too little or too much. We’ve all been a part of both of these scenarios. On the too-little side, just when a conversation gets creative the facilitator tries to pull the group back to the “task at hand” killing the creative energy in the room. On the too-much side, long after a conversation should have been cut off, people are still debating relatively unimportant or mind-numbing points. Good facilitators have to constantly try to find the balance. One trick — when you get stuck, pause the conversation and ask the room if they feel you should continue or cut the conversation. Most people are good self-assessors.

The post 3 Reasons Your Strategy Meetings Irritate Your Team appeared first on The Sundheim Group.

February 22, 2016

Bring Back the Joy In Life

There’s magic in youth. Unaware of the tensions, trade-offs, and struggles of adulthood, we’re lighter. We laugh more easily. We play more freely. We dream bigger.

Then “real life” steps in. The first disappointment. The first failure. The first break up. We start to realize that life is pretty tough. These letdowns happen again and again. We start to lower our expectations about what’s possible. Each setback is a rock we carry. No one rock is particularly big so we don’t think much of it. But all the rocks combined are a heavy load. Our shoulders slump. Our gait slows. We shuffle through the day. A degree of resignation seeps in.

We want out. But how?

The self-help-industrial complex is willing to take our money and show us “how”. I’ve read much of it. Quite frankly it bores me at this point. Some of it is cliché trash. But even the stuff that isn’t trash isn’t that helpful. It’s often academically correct, but practically clumsy—over-engineered frameworks that are too unwieldy to ever implement.

I’ve found that the most practical way to combat seeping resignation is with seeping joy. Nothing big. No silver bullets. No fancy theories. Just a day at a time. You used to love to paint—start painting. You used to love to ski—start skiing. You always wanted to play piano—take piano lessons. Do something, anything, that puts a smile on your face. It’s not about transforming your life in an instant, it’s about shifting your energy over time.

A small shift in energy here leads to another small shift there. That shift leads to another one somewhere else. Joy comes back slowly. Resignation recedes. You find you’re willing to tackle bigger and bigger challenges with each passing month and year—in every aspect of your life.

Problems are still there, but they don’t bother you as much. You feel more present. Life feels fun again.

_____________________________

[Credit for photo above: John Hudson]

The post Bring Back the Joy In Life appeared first on The Sundheim Group.

Bring Back the Joy in Life

There’s magic in youth. Unaware of the tensions, trade-offs, and struggles of adulthood, we’re lighter. We laugh more easily. We play more freely. We dream bigger.

Then “real life” steps in. The first disappointment. The first failure. The first break up. We start to realize that life is pretty tough. These letdowns happen again and again. We start to lower our expectations about what’s possible. Each setback is a rock we carry. No one rock is particularly big so we don’t think much of it. But all the rocks combined are a heavy load. Our shoulders slump. Our gait slows. We shuffle through the day. A degree of resignation seeps in.

We want out. But how?

The self-help-industrial complex is willing to take our money and show us “how”. I’ve read much of it. Quite frankly it bores me at this point. Some of it is cliché trash. But even the stuff that isn’t trash isn’t that helpful. It’s often academically correct, but practically clumsy—over-engineered frameworks that are too unwieldy to ever implement.

I’ve found that the most practical way combat seeping resignation is with seeping joy. Nothing big. No silver bullets. No fancy theories. Just a day at a time. You used to love to paint—start painting. You used to love to ski—start skiing. You always wanted to play piano—take piano lessons. Do something, anything, that puts a smile on your face. It’s not about transforming your life in an instant, it’s about shifting your energy over time.

A small shift in energy here leads to another small shift there. That shift leads to another one somewhere else. Joy comes back slowly. Resignation recedes. You find you’re willing to tackle bigger and bigger challenges with each passing month and year—in every aspect of your life.

Problems are still there, but they don’t bother you as much. You feel more present. Life feels fun again.

_____________________________

[Credit for photo above: John Hudson]

The post Bring Back the Joy in Life appeared first on The Sundheim Group.

February 16, 2016

Stand Up And Start Walking

If we listen to the chatter in our heads long enough we hear signals. Steady beacons in a sea of whimsical, transient ideas. I should do this. I should build this. I should try this. They keep pulsing, simultaneously inspiring us and pissing us off because we’re not pursuing them.

We get good at excusing ourselves from the pursuit:

I’m too young. I’m too old. I don’t have enough experience. I don’t have enough money. I don’t know the right people. I don’t have the skills. I’m not smart enough. My idea isn’t good enough. It will take too much energy. The timing isn’t right. Others (more skilled than me) have tried and failed. No one’s ever done it. No one understands it. No one will back me. If it was actually a good idea, it would have been done already.

But at some point we get tired of the excuses. We’re realize they’re lies. No one ever feels ready. No time ever feels right.

And so one day we just stand up and start walking. With wobbly legs at first. But our legs strengthen quickly. We take our licks and we realize they won’t kill us. Momentum and confidence build.

We can’t believe it took us this long. We wish we’d trusted ourselves earlier.

Start now.

The post Stand Up And Start Walking appeared first on The Sundheim Group.

February 5, 2016

Reframing Failure

When I was 24 years old, I fell into a position as the business development director at a small New York advertising agency. I had met the agency owner, Bill Markel, two weeks earlier at an advertising award show. I happened to be attending the event with a friend for the free food and drinks. As we left, Bill was standing next to me in the coat check line, holding an award he’d just won. I congratulated him, we struck up a conversation, and he mentioned that he was looking to hire someone in business development. It sounded like a great opportunity, so I threw my hat in the ring. Two weeks later, I had the job. At the time, I knew nothing about the ad industry. I was just an ambitious guy who felt that I could tackle anything with enough elbow grease. Apparently, Bill thought so too

I had no idea how tough the job would be.

Selling ad agency services is complex. You’re selling ideas, relationships, and the promise of something that people can’t touch—all for a large price tag. It’s hard enough when you have experience and know what you’re doing. It’s next to impossible when you have a baby face and an empty Rolodex.

For the first few months, I could barely find a potential client to talk to, let alone anyone to sell something to. I was quickly realizing that I’d bitten off more than I could chew. I was also questioning Bill’s judgment in having hired me in the first place. At least I could plead ignorance. But this guy had been in the business for years and should’ve known better than to put someone my age in this position. How in the world did he think that a young guy with no experience was going to waltz into the C-suites of major corporations and be taken seriously?

Every Thursday, Bill and I would review my deal pipeline. On one occasion, three months into my tenure, I was feeling particularly dejected. We were having one of those dreadful meetings that all salespeople hate—you have nothing going on and nothing to say, but you have to say something, so you just start talking.

I babbled about different deals, trying to justify my lack of progress. All the while, I was getting sick of my own voice. If I had been sitting across from myself, I’d have told me to stop talking. I was desperately hoping Bill would do just that. No such relief. Bill just let me keep going.

Finally, exasperated and out of justifications, I stopped and said, “Bill, I don’t know what I’m doing here. I think this job was a mistake for me. I don’t have enough experience to do it well, and I feel like I’m failing.”

A smirk came across Bill’s face. I remember thinking that I wasn’t in the mood for whatever “words of wisdom” he was about to share. I never appreciated a pep talk of platitudes when I was frustrated about something. But his comment was short, sweet, and exactly what I needed to hear.

“I think you’ve got it backwards,” he said.

“What do you mean?” I asked.

“You need to fail more.”

He went on to make the point that my problem wasn’t that I was failing. It was that I wasn’t failing enough. I’d take a few good swings at something, but then stop if I hadn’t gotten a hit. I wasn’t striking out enough.

For the next month, he asked me to stop bringing my sales pipeline to our weekly meetings. Instead, he wanted me to bring my strikeouts. He wanted to hear about every attempt that didn’t work out. The more the better. All of a sudden, our meetings had more levity. I felt freer to try new things.

A month later, Bill pushed me further. In my attempt to make more mistakes, I’d been pursuing a big fish—Mattel. I found out that the company would be presenting at an ad industry conference in New Orleans, and I suggested to Bill that if we could get a meeting set up in advance, we should go down and meet with them.

“I agree,” Bill replied. “But you can handle this one alone. And I think you should go even if you can’t get the meeting set up in advance. Just make the meeting happen once you get there.”

Two weeks later, against my better judgment, I was on a plane alone to New Orleans. I didn’t have a meeting set up with Mattel, and I had no game plan beyond just trying to find someone from the company to talk to. Bill’s parting words were still ringing in my ears, “Just go down there and swing the bat.”

When I got there, I felt like a teenager at his parents’ cocktail party. I had no idea whom to talk to or what to talk to them about. I had one awkward conversation after another. It started to become a little game, just trying to see how many conversations I could scare up. At the end of the second day, I finally found an opportunity to talk to a VP from Mattel as she was leaving the conference. It wasn’t the best timing, but better late than never.

I introduced myself, told her that I appreciated her presentation, and that we’d learned a few things working with M&M’S (one of our current clients) that I’d love to share with her. She gave me her business card and told me to give her a call. The whole thing lasted less than a minute. At the time, I was pretty sure she was just brushing me off. But I’d done what I was there to do, swing the bat.

When I got back to New York, I gave her a call and left a message. To my surprise, she returned the call a few hours later, and we had a good conversation. Several more conversations followed, and I got us into a pitch for a new Mattel/Intel joint venture. Six months later, after beating out two other agencies, we were awarded a half-million-dollar piece of business. It was my first significant sale, and it felt great.

What Bill knew in those early months, but I didn’t appreciate until years later, was that all those initial failures were strengthening me. Telling me to “fail more” was his way of telling me to keep training—and to stop worrying about winning the race. By the time he sent me to New Orleans, he knew I was ready. He knew I’d had enough disastrous meetings and phone calls to know what worked and what didn’t. The trip was his attempt to get me to see it. I may have chatted with the Mattel VP for only 45 seconds that day, but there were four months of failure behind that conversation—and that’s what made it a success.

I’m thankful to Bill for that lesson all those years ago. Looking back, I realize that he was doing more than giving me a paternal shot in the arm and saying, “Hey, don’t worry about it. Everyone fails. You’ll get them next time.” He was helping me reframe failure. He wanted me to see failure as a sign of progress, not of weakness or incompetence.

Excerpted and adapted from Taking Smart Risks

The post Reframing Failure appeared first on The Sundheim Group.

January 27, 2016

Why You’re On The Planet

I watch Jerry Seinfeld’s web series Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee weekly. I love the behind-the-scenes banter of comedians talking about their personal histories. It’s a rare glimpse of show-person as real person.

This week’s guest was Garry Shandling, a long-time and close friend of Seinfeld’s. Shot in LA, they visited The Comedy Story where they first met in the mid 1970’s and the studio lot where they used to hang out together (Seinfeld and The Larry Sanders Show were shot next to each other on the same lot for years which I never realized).

At one point in the episode (9:35) they get to talking about the passing of David Brenner, a father of observational comedy and a big influence on both Shandling and Seinfeld. Seinfeld asks Shandling if he ever thinks about all the material that died with Brenner (a somewhat crass question only made slightly less crass when you understand Seinfeld’s workmanlike approach to joke construction). Shandling incredulously responds, “I’m sorry, I’m at a stage in my life when I actually care about the person [not just his material].” They go back and forth a bit more on the topic and end here:

Shandling – “[His] material and your material is purely a vehicle for you to express your spirit and your soul, and your being. And that’s why you’re fantastic.”

Seinfeld – “So, [material] doesn’t have any value beyond that?”

Shandling – “It doesn’t have any value beyond you expressing yourself spiritually…that’s why you’re on the planet. When you saw Robin Williams for the first time — you don’t remember everything he said. You remember his presence.”

Well said.

For me, Shandling artfully captures the hidden value of driving towards excellence in anything. The work becomes a vehicle to express your spirit and soul.

It could be the comedian working her butt off to hone a joke over many months until it kills on stage. Or the writer throwing away page after page until the chapter reads just right. Or the leader walking the halls and listening to people day-in and day-out so that he can truly understand what’s on the everyone’s minds. We never remember every painstaking effort of these excellence-makers. But we do remember how they make us feel. Wowed. We feel their energy, love, and dedication and it inspires us.

It’s easy to forget that we all have the ability to deliver this sort of excellence. Caught up in our day-to-day routines we stop looking for the vehicles that let us dig down and express what’s in our souls. Sure, the price is an inordinate amount of hard work. But the payoff is worth it. When we do so, we touch people. We move the world.

The post Why You’re On The Planet appeared first on The Sundheim Group.

January 19, 2016

Don’t Stand for B.S. Strategic Plans

At least once a week I read a strategic plan that feels like it was written by a random-corporate-buzzword generator. The lingo sounds fancy, but there’s no substance behind it. Give it a little push and it falls apart.

Here are few recent offenders:

We’re going to utilize a best-practice project management methodology to accelerate cost cutting.

We’re going to use a brand marketing framework to increase awareness.

We need to build a culture of innovation.

We will accelerate product launches by strengthening the R&D team.

We value every voice in the organization.

To be fair, these statements aren’t inherently bad. They do mean something and can be successful strategies. But only if a clear and thoughtful plan follows. In the case of each of the five statements above there wasn’t. Rather, there were equally vague sets of implementation steps that sounded like they came from the same random corporate buzzword generator.

The problem is rampant. Why? Because we let each other get away with it. We become numb to the jargon. We sit in meetings and listen to these ideas with blank stares. We might push a little, but often we get more jargon back as the answer, so we just let it go. The BS just piles higher.

Take back your own planning documents, your meetings, your daily interactions. Call people on the BS. Demand they’re clear on what they actually mean. The steps, the timelines, the risks, the open questions.

If you aren’t clear on what someone is saying, there’s a good chance no one else is either.

The post Don’t Stand for B.S. Strategic Plans appeared first on The Sundheim Group.