Muthukrishnan's Blog

December 8, 2017

Private Capitalism – Notions from the Book

“The reduction in inequality after the Second World was an exception to the general rule of capitalism” – Thomas Piketty

The Book aims to supplement “Conventional” perspectives by giving an economic history of capitalism and digital technology while recognizing the diversity of economic forms and the competitive tensions inherent in the contemporary economy. The simple wager of the book is that we can learn a lot about major tech companies by taking them to be economic actors within a capitalist mode of production.

[image error]

These neo-digital giants reach out further and further into our digital infrastructure and as society becomes increasingly reliant upon them, it is crucial that we understand how they function and what can be done. Building a better future demands it. We continue to live in a capitalist society where competition and profit-seeking provide the general parameters of our world. On the other side of the class relation, some argue that the economy today is dominated by a new class, which does not own the means of production but rather has ownership over information.

Google has around 60,000 direct employees, Facebook has 12,000, while WhatsApp had 55 employees when it was sold to Facebook for $ 19 billion and Instagram had 13 when it was purchased for $ 1 billion. By comparison, in 1962 the most significant companies employed far larger numbers of workers: AT& T had 564,000 employees, Exxon had 150,000 workers, and GM had 605,000 employees.

What are platforms?

At the most general level, platforms are digital infrastructures that enable two or more groups to interact.

What Platforms do?

This is the key to its advantage over traditional business models when it comes to data, since a platform positions itself (1) between users, and (2) as the ground upon which their activities occur, which thus gives it privileged access to record them. In their position as an intermediary, platforms gain not only access to more data but also control and governance over the rules of the game.

If you want to join a platform for socializing, you join the platform where most of your friends and family already are (Like Facebook or Twitter). Likewise, the more numerous the users who search on Google, the better their search algorithms become, and the more useful Google becomes to users. But this generates a cycle whereby more users beget more users, which leads to platforms having a natural tendency towards monopolization.

How do Platforms work?

Platform ownership, in turn, is essentially ownership of software (the 2 billion lines of code for Google, or the 20 million lines of code for Facebook) 18 and hardware (servers, data centres, smartphones, etc.), built upon open-source material (e.g. Hadoop’s data management system is used by Facebook).

In spite of its numerous obituaries of Compact Discs and other physical forms of music in the early 2000s, the music industry has been revived in recent years by platforms (Spotify, Pandora) that syphon off fees from music listeners, record labels, and advertisers alike. Between 2010 and 2014 subscription services have seen user numbers rise up from 8 million to 41 million, and subscription revenues are set to overtake download revenues as the highest source of digital music. After years of decline, the music industry is poised to see its revenue growth once again in 2016. While subscription models have been around for centuries, for example in newspapers, what is novel today is their expansion to new realms: housing, cars, toothbrushes, razors, even private jets.

The challenge with maintenance is that it is quite easy for outside competitors to come into the market and take the profits away. This prompted Rolls Royce to introduce the ‘goods as a service’model, whereby airlines do not purchase the jet engine but pay a fee for every hour one is used. In turn, Rolls Royce provides maintenance and replacement parts. The raw material of data remains as central to this platform as to any other. Sensors are placed on all the engines and massive amounts of data are extracted from every flight, combined with weather data and information on air traffic control, and sent to a command centre in the United Kingdom

‘lean’ platforms like Uber, ‘the world’s largest taxi company, owns no vehicles’ and Airbnb, ‘the largest accommodation provider, owns no property’. It would seem that these are asset-less companies; we might call them virtual platforms. Yet the key is that they do own the most important asset: the platform of software and data analytics.

The most notorious part of these firms is their outsourcing of workers. In America, these platforms legally understand their workers as ‘independent contractors’rather than ‘employees’. This enables the companies to save around 30 percent on labour costs by cutting out benefits, overtime, sick days, and other costs. It also means outsourcing training costs, since training is only permitted for employees; and this process has led to alternatives forms of control via reputation systems, which often transmit the gendered and racist biases of society. Outsourcing once primarily took place in manufacturing, administration, and hospitality, today it is extending to a range of new jobs: cabs, haircuts, stylists, cleaning, plumbing, painting, moving, content moderation, and so on. It is even pushing into white-collar jobs – copy-editing, programming and management, for instance. The calculations of one class action lawsuit estimate that Uber would owe its drivers $ 852 million if they were employees (Uber claims it would only be $ 429 million). To fight off one competitor, for instance, Uber took to calling up and cancelling rides with its rival, in an effort to clog up that rival’s supply of drivers.

Will competition survive in the digital era, or are we headed for a new monopoly capitalism?

We give Google access to our email, our calendars, our video histories, our search histories, our locations – and, with each aspect provided to Google, we get better predictive services as a result. Likewise, platforms aim to facilitate complementary products: useful software built for Android leads more users to use Android, which leads more developers to develop for Android, and so on, in a virtuous circle. We can get a sense of how significant these monopolies already are by looking at how they consolidate ad revenue: in 2016 Facebook, Google, and Alibaba alone will take half of the world’s digital advertising.

Yet it is also true that capitalism develops not only greater means for the monopoly but also greater means for competition.

Despite their differences, companies like Facebook, Google, Microsoft, Amazon, Alibaba, Uber, and General Electric (GE) are also direct competitors. IBM, for instance, has moved into the platform business, purchasing Softlayer for cloud computing, and BlueMix for software development. The convergence thesis helps explain why Google is lobbying with Uber on self-driving cars and why Amazon and Microsoft have been discussing partnerships with German automakers on the cloud platform required by self-driving Ultimately, we see convergence – and therefore competition – across the field: smartphones, e-book readers, consumer IoT, cloud platforms, video-chat services, payment services, driverless cars, drones, virtual reality, social networking, interfaces, network provision, search, and probably much more in the future.

The expansion of smartphones has led to more and more users interacting with the internet through apps rather than by visiting websites, and this is a way in which companies can both expand and close off data collection. As more users head into an app, those data are extracted there, while other platforms lose out. Dropbox is spending large amounts of money to separate itself from Amazon Web Services, and Uber is seeking to untie itself from dependency on Google Maps. Even deeper down the stack, platforms are at work building their own network infrastructure. Google, for instance, has been building its own privatized internet –browsers, OSs, fibre networks, and data centres –where information may never have to journey across the public infrastructure. Likewise, Amazon’s cloud network is nothing if not a private internet, and Microsoft and Facebook are collaborating to build their own transatlantic fibre cable.

While most of the other platform types appear to be in a strong enough position to weather any economic crisis and any blow to their business model, advertising platforms remain precariously dependent on ad revenues (e.g. Google at 89.0 percent and Facebook at 96.6 percent). It is, though, unclear whether advertising can thrive in a world of ad blockers, bots causing fake ad views, and routine spam. Even Google’s chief economist, Hal Varian, expects that advertising will decline in importance and that Google will eventually move towards a pay-per-view model, and could be compelled to more into direct payment businesses. Meanwhile, lean platforms dependent on outsourcing costs and on venture capital largesse either go bankrupt or shift into product platforms (as Uber is attempting to do with driverless cars).

“Yet even limiting our attention to user-created data, it is right to call this activity labour?”

Rather than just regulating corporate platforms, efforts could be made to create public platforms – platforms owned and controlled by the people. (And, importantly, independent of the surveillance state apparatus) is all one could think of the better futuristic world. And all I could feel reading this work is, that at least I can reduce my time spending on these platforms. It’s better not to be too much reliant upon these uncertain Platform Capitalists.

[image error]

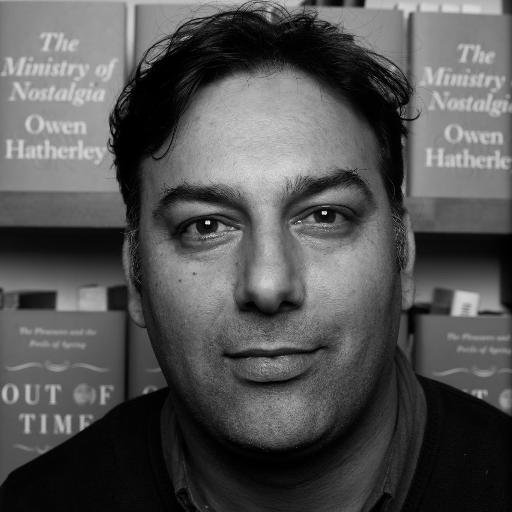

Nick Srnicek He’s an American writer and academic, currently a lecturer in Digital Economy at King’s College London. One of the very few intellectuals who think “Luxury Communism” will win.

He’s an American writer and academic, currently a lecturer in Digital Economy at King’s College London. One of the very few intellectuals who think “Luxury Communism” will win.

December 1, 2017

Waking Up: A Guide to Spirituality without Religion – Book Review

Try devouring this Buddhist Parable:

“A man is struck in the chest with a poison arrow. A surgeon rushes to his side to begin the work of saving his life, but the man resists these ministrations. He first wants to know the name of the fletcher who fashioned the arrow’s shaft, the genus of the wood from which it was cut, the disposition of the man who shot it, the name of the horse upon which he rode, and a thousand other things that have no bearing upon his present suffering or his ultimate survival. The man needs to get his priorities straight. His commitment to thinking about the world results from a basic misunderstanding of his predicament. And though we may be only dimly aware of it, we, too, have a problem that will not be solved by acquiring more conceptual knowledge.”

The term Spirituality has more colluded with Religious doctrines obliviously. And in time, many presume that both are the two sides of the same coin. Astronomers and Astrophysicists, Physicists like Sagan, Neil Tyson, Brian Cox get some of us ‘spiritually’ enlightened, getting awe with the depth of understanding which previously believed impossible when they started talking about their specialized fields. Some Writers like Shakespeare, Kurt Vonnegut(personal option) made many people realize that they could lead a happier life, prouder to be alive than previously believed possible. Musical artists like Beethoven, Mozart made the same using the tools and medium they knew. Now, take a religious person listening to a ‘Spiritual’ Guru, he would feel connected and profound relevance of one’s existence with respect to that Guruji’s words and view of the world. Sam Harris connects the word with understanding the brain and its contents both physical and emergent, of course the rational content free of dogmas and bullshit stuffs, which is equally important to know the worldly facts and phenomena.

The Book deals with signifying the importance of being “spiritual” which the author implies removing the illusion of self. By “illusion of self” he meant that the illusion of inner-self, some kind of agenticity within our body having control over it which adds up concepts of soulful mind duality, and freewill stuffs. And breaking this illusion of the self, he says that our minds can have different and better conscious experiences irrespective of our emotional states. It’s not a matter of thinking more clearly about the experience; it is the act of experiencing more clearly, including the arising of thoughts themselves and the problem is not thoughts themselves but the state of thinking without being fully aware that we are thinking. Even though he explained things in simpler terms, I felt like I was listening to the most complicated man alive. He explored the split-brain phenomena, Nature of Consciousness, Contemporary meditation techniques as per the western as well as the Eastern cultural and psychological understanding, the yogis, gurus who were considered as enlightened (still many consider themselves enlightened) in context to the core objective of enabling the readers to understand about our mind a little better and more profound. He also had his exquisite intellectual ponderings on the effects and usage of drugs. The term drugs collectively define a wide variety of neurotransmitters and chemical enhancers of neural activities in which substances in both categories have both neurotoxic, epileptic as well as excrescence enhancing tool for consciousness. Collectively labeling them as ‘drugs’ disables us to have an intellectual discussion on the ethical, psychological, biological, legal effects and usage of such substances like Psilocybin, DMT, Ketamine, LSD, MDMA (commonly known as Ecstasy), etc.,. It is also worth noting that some substances stereotypically labeled as ‘drug’ have lesser effects than widely legalized Alcoholics and tobacco.

“The power of psychedelics, however, is that they often reveal, in the span of a few hours, depths of awe and understanding that can otherwise elude us for a lifetime.”

He repeated the phenomena many times with various illustrations to make sure the listeners/readers could really understand and ponder out the stuffs. As Carl Sagan once said, Brain is a small place with a very enormous space and capabilities.

He used fluids to define the nature and physical foundation of consciousness, as emergent phenomena.

“Consciousness is the prior condition of every experience; the self or ego is an illusory appearance within it; look closely for what you are calling, and the feeling of being a separate self will disappear; what remains, as a matter of experience, is a field of consciousness—free, undivided, and intrinsically uncontaminated by its ever-changing contents.”

Even though I’ve already read a book of Sam Harris on Free Will, I got to know more about him than being a skeptical neuroscience spokesperson while exploring this work. His early life encounters with drugs, in search of his spiritual encounters inside the USA. While he was in his 2nd year at Stanford, he took off 11 years to spend time in India and Nepal, trying to understand the case of which he described briefly in this book.

“I have long argued that confusion about the unity of religions is an artifact of language. Religion is a term like sports: Some sports are peaceful but spectacularly dangerous (“free solo” rock climbing); some are safer but synonymous with violence (mixed martial arts); and some entail little more risk of injury than standing in the shower (bowling). To speak of sports as a generic activity makes it impossible to discuss what athletes actually do or the physical attributes required to do it. What do all sports have in common apart from breathing? Not much. The term religion is hardly more useful.

The same could be said of spirituality. The esoteric doctrines found within every religious tradition are not all derived from the same insights. Nor are they equally empirical, logical, parsimonious, or wise. They don’t always point to the same underlying reality—and when they do, they don’t do it equally well.”

Well for the general audience, there’s nothing novel about this work; It is just about trying to become happy. The Conventional sources of happiness aren’t always reliable depending upon various transient conditions. It is difficult to raise a family happily, to keep yourself and the people you love healthy, to acquire wealth and find creative and fulfilling ways to enjoy it, to form deep relationships, to contribute to society in ways that are emotionally rewarding, to perfect a wide variety of skills—and to keep the machinery of happiness running day after day.

See if you can stop thinking for the next sixty seconds. You can notice your breath, or listen to the birds, but do not let your attention be carried away by thought, any thought, even for an instant. Keep away from mobile or computer, and give it a try.

“If your golf instructor were to insist that you shave your head, sleep no more than four hours each night, renounce sex, and subsist on a diet of raw vegetables, you would find a new golf instructor.”

There is no question that novel and intense experiences—whether had in the company of a guru, on the threshold of death, or by recourse to certain drugs—can send one spinning into delusion. But they can also broaden one’s view.

Before trying this book, I’ve checked the reviews of this work and found too many negative receptions about it. Many of them indicated themselves as ardent followers of Sam Harris by his support and critical views on religion and his science popularizing façade but disappointed with Sam Harris for supporting the Meditation via Buddhist techniques and this illusionary concept of ‘self’ and many didn’t feel like it’s science at all because of confusing usage of consciousness. Sam did answer those things in the book itself,

“Search your mind, or pay attention to the conversations you have with other people, and you will discover that there are no real boundaries between science and any other discipline that attempts to make valid claims about the world on the basis of evidence and logic. When such claims and their methods of verification admit of experiment and/or mathematical description, we tend to say that our concerns are scientific; when they relate to matters more abstract, or to the consistency of our thinking itself, we often say that we are being philosophical; when we merely want to know how people behaved in the past, we dub our interests historical or journalistic; and when a person’s commitment to evidence and logic grows dangerously thin or simply snaps under the burden of fear, wishful thinking, tribalism, or ecstasy, we recognize that he is being religious.”

Overall, I feel the book is well worth reading, pondering out our brain stuffs. Though the brief summary of the book is very simple but one has to go through every word vigilantly, to avoid confusion, to avoid misconceptions. So I wouldn’t recommend it for all.

Sam Harris is the author of five New York Times bestsellers. His books include The End of Faith, Letter to a Christian Nation, The Moral Landscape, Free Will, Lying, Waking Up, and Islam and the Future of Tolerance (with Maajid Nawaz). The End of Faith won the 2005 PEN Award for Nonfiction. His writing and public lectures cover a wide range of topics—neuroscience, moral philosophy, religion, meditation practice, human violence, rationality—but generally focus on how a growing understanding of ourselves and the world is changing our sense of how we should live.

Harris’s work has been published in more than 20 languages and has been discussed in The New York Times, Time, Scientific American, Nature, Newsweek, Rolling Stone, and many other journals. He has written for The New York Times, The Los Angeles Times, The Economist, The Times (London), The Boston Globe, The Atlantic, The Annals of Neurology, and elsewhere. Harris also regularly hosts a popular podcast.

Advertisements

February 14, 2017

The Value of Science ft. Richard Feynman

Of all its many values, the greatest must be the freedom to doubt.

“The Value of Science” was given as a public address at the 1955 autumn meeting of the National Academy of Sciences. held on the Caliech campus November 2, 3 and 4.

FROM TIME TO TIME, people suggest to me that scientists ought to give more consideration to social problems – especially that they should be more responsible in considering the impact of science upon society. This same suggestion must he made to many other scientists, and it seems a be generally believed that if the scientists would only look at these very difficult social problems and not spend so much time fooling with the less vital scientific ones, great success would come of it.

It seems to me that we do think about these problems from time to time, but we don’t put full‑time effort on them – the reason being that we know we don’t have any magic formula for solving problems, that social problems are very much harder than scientific ones, and that we usually don’t get anywhere when we do think about them.

I believe that a scientist looking at non‑scientific problems is just as dumb as the next guy – and when he talks about a non‑scientific matter, he will sound as naive as anyone untrained in the matter. Since the question of the value of science is not a scientific subject, this talk is dedicated to proving my point – by example.

The first way in which science is of value is familiar to everyone. It is that scientific knowledge enables us to do all kinds of things and to make all kinds of things. Of course if we make good things, it is not only to the credit of science; it is also to the credit of the moral choice which led us to good work. Scientific knowledge is an enabling power to do either good or had‑hut it does not carry instructions on how to use it. Such power has evident value – even though the power may be negated by what one does.

I learned a way of expressing this common human problem on a trip to Honolulu. In a Buddhist temple there, the man in charge explained a little bit about the Buddhist religion for tourists, and then ended his talk by telling them he had something to say to them that they would never forget – and I have never forgotten it. It was a proverb of the Buddhist religion:

“To every man is given the key to the gates of heaven ; the same key opens the gates of hell.”

What then, is the value of the key to heaven? It is true that if we lack clear instructions that determine which is the gate to heaven and which the gate to hell, the key may be a dangerous object to use, but it obviously has value. How can we enter heaven without it?

The instructions, also, would be of no value without the key. So it is evident that, in spite of the fact that science could produce enormous horror in the world it is of value because it can produce something.

Another value of science is the fun called intellectual enjoyment which some people get from reading and learning and thinking about it, and which others get from working in it. This is a very real and important point and one which is not considered enough by those who tell us it is our social responsibility to reflect on the impact of science on society.

Is this mere personal enjoyment of value to society as a whole? No! But it is also a responsibility to consider the value of society itself. Is it, in the last analysis, to arrange things so that people can enjoy things? If so, the enjoyment of science is as important as anything else.

But I would like not to underestimate the value of the world view which is the result of scientific effort. We have been led to imagine all sorts of things infinitely more marvelous than the imaginings Of poets and dreamers of the past. It shows that the imagination of nature is far, far greater than the imagination of man. For instance, how much more remarkable it is for us all to be stuck – half of us upside down – by a mysterious attraction, to a spinning ball that has been swinging in space for billions of years, than to be carried on the back of an elephant supported on a tortoise swimming in a bottomless sea.

I have thought about these things so many times alone that I hope you will excuse me if I remind you of some thoughts that I am sure you have all had – or this type of thought – which no one could ever have had in the past, because people then didn’t have the information we have about the world today.

For instance, I stand at the seashore, alone, and start to think. There are the rushing waves . . . mountains of molecules, each stupidly minding its own business . . trillions apart . . . yet forming white surf in unison.

Ages on ages . . . before any eyes could see . . year after year . . . thunderously pounding the shore as now. For whom, for what? . . . on a dead planet, with no life to entertain.

Never at rest . . . tortured by energy . . . wasted prodigiously by the sun . . . poured into space. A mite makes the sea roar.

Deep in the sea, all molecules repeat the patterns of one another till complex new ones are formed. They make others like themselves . . . and a new dance starts.

Growing in size and complexity . . . living things, masses of atoms, DNA, protein dancing a pattern ever more intricate.

Out of the cradle onto the dry land here it is standing . . . atoms with consciousness . . . matter with curiosity.

Stands at the sea . . . wonders at wondering . . . I . . . a universe of atoms . . . an atom in the universe.

THE GRAND ADVENTURE

The same thrill, the same awe and mystery, come again and again when we look at any problem deeply enough. With more knowledge comes deeper, more wonderful mystery, luring one on to penetrate deeper still. Never concerned that the answer may prove disappointing, but with pleasure and confidence we turn over each new stone to find unimagined strangeness leading to more wonderful questions and mysteries – certainly a grand adventure!

It is true that few unscientific people have this type of religious experience. Our poets do not write about it; our artists do not try to portray this remarkable thing. I don’t know why. Is nobody inspired by our present picture of the universe? The value of science remains still unsung by singers, so you are reduced to hearing – not a song or poem, but an evening lecture about it. This is not yet a scientific age.

Perhaps one of the reasons is that you have to know how to read the music. For instance, the scientific article says, perhaps, something like this: “The radioactive phosphorous content of the cerebrum of the rat decreases to one‑half in a period of two weeks.” Now what does that mean?

It means that phosphorus that is in the brain of a rat (and also in mine, and yours is not the same phosphorus as it was two weeks ago, but that all of the atoms that are in the brain are being replaced, and the ones that were there before have gone away.

So what is this mind, what are these atoms with consciousness? Last week’s potatoes! That is what now can remember what was going on in my mind a year ago – a mind which has long ago been replaced.

That is what it means when one discovers how long it takes for the atoms of the brain to be replaced by other atoms, to note that the thing which I call my individuality is only a pattern or dance. The atoms come into my brain, dance a dance, then go out always new atoms but always doing the same dance, remembering what the dance was yesterday.

THE REMARKABLE IDEA

When we read about this in the newspaper, it says, “The scientist says that this discovery may have importance in the cure of cancer.” The paper is only interested in the use of the idea, not the idea itself. Hardly anyone can understand the importance of an idea, it is so remarkable. Except that, possibly, some children catch on. And when a child catches on to an idea like that, we have a scientist. These ideas do filter down (in spite of all the conversation about TV replacing thinking), and lots of kids get the spirit – and when they have the spirit you have a scientist. It’s too late for them to get the spirit when they are in our universities, so we must attempt to explain these ideas to children.

I would now like to turn to a third value that science has. It is a little more indirect, but not much. The scientist has a lot of experience with ignorance and doubt and uncertainty, and this experience is of very great importance, I think. When a scientist doesn’t know the answer to a problem, he is ignorant. When he has a hunch as to what the result is, he is uncertain. And when he is pretty darn sure of what the result is going to be, he is in some doubt. We have found it of paramount importance that in order to progress we must recognize the ignorance and leave room for doubt. Scientific knowledge is a body of statements of varying degrees of certainty – some most unsure, some nearly sure, noneabsolutely certain.

Now. we scientists are used to this, and we take it for granted that it is perfectly consistent to he unsure – that it is possible to live and not know. But I don’t know whether everyone realizes that this is true. Our freedom to doubt was born of a struggle against authority in the early days of science. It was a very deep and strong struggle. Permit us to question – to doubt, that’s all – not to be sure. And I think it is important that we do not forget the importance of this struggle and thus perhaps lose what we have gained. Here lies a responsibility to society.

We are all sad when we think of the wondrous potentialities human beings seem to have, as contrasted with their small accomplishments. Again and again people have thought that we could do much better. They of the past saw in the nightmare of their times a dream for the future. We, of their future, see that their dreams, in certain ways surpassed, have in many ways remained dreams. The hopes for the future today are, in good share, those of yesterday.

EDUCATION, FOR GOOD AND EVIL

Once some thought that the possibilities people had were not developed because most of these people were ignorant. With education universal, could all men be Voltaires? Bad can be taught at least as efficiently as good. Education is a strong force, but for either good or evil.

Communications between nations must promote understanding: so went another dream. But the machines of communication can be channeled or choked. What is communicated can be truth or lie. Communication is a strong force also, but for either good or bad.

The applied sciences should free men of material problems at least. Medicine controls diseases. And the record here seems all to the good. Yet there are men patiently working to create great plagues and poisons. They are to be used in warfare tomorrow.

Nearly everybody dislikes war. Our dream today is peace. In peace, man can develop best the enormous possibilities he seems to have. But maybe future men will find that peace, too, can be good and bad. Perhaps peaceful men will drink out of boredom. Then perhaps drink will become the great problem which seems to keep man from getting all he thinks he should out of his abilities.

Clearly, peace is a great force, as is sobriety, as are material power, communication, education, honesty and the ideals of many dreamers.

We have more of these forces to control than did the ancients. And maybe we are doing a little better than most of them could do. But what we ought to be able to do seems gigantic compared with our confused accomplishments,

Why is this? Why can’t we conquer ourselves?

Because we find that even great forces and abilities do not seem to carry with them clear instructions on how to use them. As an example, the great accumulation of understanding as to how the physical world behaves only convinces one that this behavior seems to have a kind of meaninglessness. The sciences do not directly teach good and bad.

Through all ages men have tried to fathom the meaning of life. They have realized that if some direction or meaning could be given to our actions, great human forces would be unleashed. So, very many answers have been given to the question of the meaning of it all, But they have all been of different sorts, and the proponents of one answer have looked with horror at the actions of the believers in another. Horror, because from a disagreeing point of view all the great potentialities of this race were being channeled into a false and confining blind alley. In fact, it is from the history of the enormous monstrosities created by false belief that philosophers have realized the apparently infinite and wondrous capacities of human beings. The dream is to find the open channel.

What, then, is the meaning of it all? What can we say to dispel the mystery of existence?

If we take everything into account, not only what the ancients knew, but all of what we know today that they didn’t know, then I think that we must frankly admit that we do not know.

This is not a new idea; this is the idea of the age of reason. This is the philosophy that guided the men who made the democracy that we live under. The idea that no one really knew how to run a government led to the idea that we should arrange a system by which new ideas could be developed, tried out, tossed out, more new ideas brought in; a trial and error system. This method was a result of the fact that science was already showing itself to be a successful venture at the end of the 18th century. Even then it was clear to socially‑minded people that the openness of the possibilities was an opportunity, and it that doubt and discussion were essential to progress into the unknown. If we want to solve a problem that we have never solved before, we must leave the door to the unknown ajar.

OUR RESPONSIBILITY, AS SCIENTISTS

We are at the very beginning of time for the human race. It is not unreasonable that we grapple with problems. There are tens of thousands of years in the future. Our responsibility is to do what we can, learn what we can, improve the solutions and pass them on. It is our responsibility to leave the men of the future a free hand. In the impetuous youth of humanity, we can make grave errors that can stunt our grow for a long time. This we will do if we say we have the answers now, so young and ignorant; if we suppress all discussion, all criticism, saying, “This is it, boys, man is saved!” and thus doom man for a long time to the chains of authority, confined to the limits of our present imagination. It has been done so man lines before.

It is our responsibility as scientists, knowing the great progress and great value of a satisfactory philosophy of ignorance, the great progress that is the fruit of freedom of thought, to proclaim the value of this freedom, to teach how doubt is not to be feared but welcomed and discussed, and to demand this freedom as our duty to all coming generations.

The Value of Science ft. Richard Feynman

Of all its many values, the greatest must be the freedom to doubt.

“The Value of Science” was given as a public address at the 1955 autumn meeting of the National Academy of Sciences. held on the Caliech campus November 2, 3 and 4.

FROM TIME TO TIME, people suggest to me that scientists ought to give more consideration to social problems – especially that they should be more responsible in considering the impact of science upon society. This same suggestion must he made to many other scientists, and it seems a be generally believed that if the scientists would only look at these very difficult social problems and not spend so much time fooling with the less vital scientific ones, great success would come of it.

It seems to me that we do think about these problems from time to time, but we don’t put full‑time effort on them – the reason being that we know we don’t have any magic formula for solving problems, that social problems are very much harder than scientific ones, and that we usually don’t get anywhere when we do think about them.

I believe that a scientist looking at non‑scientific problems is just as dumb as the next guy – and when he talks about a non‑scientific matter, he will sound as naive as anyone untrained in the matter. Since the question of the value of science is not a scientific subject, this talk is dedicated to proving my point – by example.

The first way in which science is of value is familiar to everyone. It is that scientific knowledge enables us to do all kinds of things and to make all kinds of things. Of course if we make good things, it is not only to the credit of science; it is also to the credit of the moral choice which led us to good work. Scientific knowledge is an enabling power to do either good or had‑hut it does not carry instructions on how to use it. Such power has evident value – even though the power may be negated by what one does.

I learned a way of expressing this common human problem on a trip to Honolulu. In a Buddhist temple there, the man in charge explained a little bit about the Buddhist religion for tourists, and then ended his talk by telling them he had something to say to them that they would never forget – and I have never forgotten it. It was a proverb of the Buddhist religion:

“To every man is given the key to the gates of heaven ; the same key opens the gates of hell.”

What then, is the value of the key to heaven? It is true that if we lack clear instructions that determine which is the gate to heaven and which the gate to hell, the key may be a dangerous object to use, but it obviously has value. How can we enter heaven without it?

The instructions, also, would be of no value without the key. So it is evident that, in spite of the fact that science could produce enormous horror in the world it is of value because it can produce something.

Another value of science is the fun called intellectual enjoyment which some people get from reading and learning and thinking about it, and which others get from working in it. This is a very real and important point and one which is not considered enough by those who tell us it is our social responsibility to reflect on the impact of science on society.

Is this mere personal enjoyment of value to society as a whole? No! But it is also a responsibility to consider the value of society itself. Is it, in the last analysis, to arrange things so that people can enjoy things? If so, the enjoyment of science is as important as anything else.

But I would like not to underestimate the value of the world view which is the result of scientific effort. We have been led to imagine all sorts of things infinitely more marvelous than the imaginings Of poets and dreamers of the past. It shows that the imagination of nature is far, far greater than the imagination of man. For instance, how much more remarkable it is for us all to be stuck – half of us upside down – by a mysterious attraction, to a spinning ball that has been swinging in space for billions of years, than to be carried on the back of an elephant supported on a tortoise swimming in a bottomless sea.

I have thought about these things so many times alone that I hope you will excuse me if I remind you of some thoughts that I am sure you have all had – or this type of thought – which no one could ever have had in the past, because people then didn’t have the information we have about the world today.

For instance, I stand at the seashore, alone, and start to think. There are the rushing waves . . . mountains of molecules, each stupidly minding its own business . . trillions apart . . . yet forming white surf in unison.

Ages on ages . . . before any eyes could see . . year after year . . . thunderously pounding the shore as now. For whom, for what? . . . on a dead planet, with no life to entertain.

Never at rest . . . tortured by energy . . . wasted prodigiously by the sun . . . poured into space. A mite makes the sea roar.

Deep in the sea, all molecules repeat the patterns of one another till complex new ones are formed. They make others like themselves . . . and a new dance starts.

Growing in size and complexity . . . living things, masses of atoms, DNA, protein dancing a pattern ever more intricate.

Out of the cradle onto the dry land here it is standing . . . atoms with consciousness . . . matter with curiosity.

Stands at the sea . . . wonders at wondering . . . I . . . a universe of atoms . . . an atom in the universe.

THE GRAND ADVENTURE

The same thrill, the same awe and mystery, come again and again when we look at any problem deeply enough. With more knowledge comes deeper, more wonderful mystery, luring one on to penetrate deeper still. Never concerned that the answer may prove disappointing, but with pleasure and confidence we turn over each new stone to find unimagined strangeness leading to more wonderful questions and mysteries – certainly a grand adventure!

It is true that few unscientific people have this type of religious experience. Our poets do not write about it; our artists do not try to portray this remarkable thing. I don’t know why. Is nobody inspired by our present picture of the universe? The value of science remains still unsung by singers, so you are reduced to hearing – not a song or poem, but an evening lecture about it. This is not yet a scientific age.

Perhaps one of the reasons is that you have to know how to read the music. For instance, the scientific article says, perhaps, something like this: “The radioactive phosphorous content of the cerebrum of the rat decreases to one‑half in a period of two weeks.” Now what does that mean?

It means that phosphorus that is in the brain of a rat (and also in mine, and yours is not the same phosphorus as it was two weeks ago, but that all of the atoms that are in the brain are being replaced, and the ones that were there before have gone away.

So what is this mind, what are these atoms with consciousness? Last week’s potatoes! That is what now can remember what was going on in my mind a year ago – a mind which has long ago been replaced.

That is what it means when one discovers how long it takes for the atoms of the brain to be replaced by other atoms, to note that the thing which I call my individuality is only a pattern or dance. The atoms come into my brain, dance a dance, then go out always new atoms but always doing the same dance, remembering what the dance was yesterday.

THE REMARKABLE IDEA

When we read about this in the newspaper, it says, “The scientist says that this discovery may have importance in the cure of cancer.” The paper is only interested in the use of the idea, not the idea itself. Hardly anyone can understand the importance of an idea, it is so remarkable. Except that, possibly, some children catch on. And when a child catches on to an idea like that, we have a scientist. These ideas do filter down (in spite of all the conversation about TV replacing thinking), and lots of kids get the spirit – and when they have the spirit you have a scientist. It’s too late for them to get the spirit when they are in our universities, so we must attempt to explain these ideas to children.

I would now like to turn to a third value that science has. It is a little more indirect, but not much. The scientist has a lot of experience with ignorance and doubt and uncertainty, and this experience is of very great importance, I think. When a scientist doesn’t know the answer to a problem, he is ignorant. When he has a hunch as to what the result is, he is uncertain. And when he is pretty darn sure of what the result is going to be, he is in some doubt. We have found it of paramount importance that in order to progress we must recognize the ignorance and leave room for doubt. Scientific knowledge is a body of statements of varying degrees of certainty – some most unsure, some nearly sure, noneabsolutely certain.

Now. we scientists are used to this, and we take it for granted that it is perfectly consistent to he unsure – that it is possible to live and not know. But I don’t know whether everyone realizes that this is true. Our freedom to doubt was born of a struggle against authority in the early days of science. It was a very deep and strong struggle. Permit us to question – to doubt, that’s all – not to be sure. And I think it is important that we do not forget the importance of this struggle and thus perhaps lose what we have gained. Here lies a responsibility to society.

We are all sad when we think of the wondrous potentialities human beings seem to have, as contrasted with their small accomplishments. Again and again people have thought that we could do much better. They of the past saw in the nightmare of their times a dream for the future. We, of their future, see that their dreams, in certain ways surpassed, have in many ways remained dreams. The hopes for the future today are, in good share, those of yesterday.

EDUCATION, FOR GOOD AND EVIL

Once some thought that the possibilities people had were not developed because most of these people were ignorant. With education universal, could all men be Voltaires? Bad can be taught at least as efficiently as good. Education is a strong force, but for either good or evil.

Communications between nations must promote understanding: so went another dream. But the machines of communication can be channeled or choked. What is communicated can be truth or lie. Communication is a strong force also, but for either good or bad.

The applied sciences should free men of material problems at least. Medicine controls diseases. And the record here seems all to the good. Yet there are men patiently working to create great plagues and poisons. They are to be used in warfare tomorrow.

Nearly everybody dislikes war. Our dream today is peace. In peace, man can develop best the enormous possibilities he seems to have. But maybe future men will find that peace, too, can be good and bad. Perhaps peaceful men will drink out of boredom. Then perhaps drink will become the great problem which seems to keep man from getting all he thinks he should out of his abilities.

Clearly, peace is a great force, as is sobriety, as are material power, communication, education, honesty and the ideals of many dreamers.

We have more of these forces to control than did the ancients. And maybe we are doing a little better than most of them could do. But what we ought to be able to do seems gigantic compared with our confused accomplishments,

Why is this? Why can’t we conquer ourselves?

Because we find that even great forces and abilities do not seem to carry with them clear instructions on how to use them. As an example, the great accumulation of understanding as to how the physical world behaves only convinces one that this behavior seems to have a kind of meaninglessness. The sciences do not directly teach good and bad.

Through all ages men have tried to fathom the meaning of life. They have realized that if some direction or meaning could be given to our actions, great human forces would be unleashed. So, very many answers have been given to the question of the meaning of it all, But they have all been of different sorts, and the proponents of one answer have looked with horror at the actions of the believers in another. Horror, because from a disagreeing point of view all the great potentialities of this race were being channeled into a false and confining blind alley. In fact, it is from the history of the enormous monstrosities created by false belief that philosophers have realized the apparently infinite and wondrous capacities of human beings. The dream is to find the open channel.

What, then, is the meaning of it all? What can we say to dispel the mystery of existence?

If we take everything into account, not only what the ancients knew, but all of what we know today that they didn’t know, then I think that we must frankly admit that we do not know.

This is not a new idea; this is the idea of the age of reason. This is the philosophy that guided the men who made the democracy that we live under. The idea that no one really knew how to run a government led to the idea that we should arrange a system by which new ideas could be developed, tried out, tossed out, more new ideas brought in; a trial and error system. This method was a result of the fact that science was already showing itself to be a successful venture at the end of the 18th century. Even then it was clear to socially‑minded people that the openness of the possibilities was an opportunity, and it that doubt and discussion were essential to progress into the unknown. If we want to solve a problem that we have never solved before, we must leave the door to the unknown ajar.

OUR RESPONSIBILITY, AS SCIENTISTS

We are at the very beginning of time for the human race. It is not unreasonable that we grapple with problems. There are tens of thousands of years in the future. Our responsibility is to do what we can, learn what we can, improve the solutions and pass them on. It is our responsibility to leave the men of the future a free hand. In the impetuous youth of humanity, we can make grave errors that can stunt our grow for a long time. This we will do if we say we have the answers now, so young and ignorant; if we suppress all discussion, all criticism, saying, “This is it, boys, man is saved!” and thus doom man for a long time to the chains of authority, confined to the limits of our present imagination. It has been done so man lines before.

It is our responsibility as scientists, knowing the great progress and great value of a satisfactory philosophy of ignorance, the great progress that is the fruit of freedom of thought, to proclaim the value of this freedom, to teach how doubt is not to be feared but welcomed and discussed, and to demand this freedom as our duty to all coming generations.

The Value of Science ft. Richard Feynman

Of all its many values, the greatest must be the freedom to doubt.

“The Value of Science” was given as a public address at the 1955 autumn meeting of the National Academy of Sciences. held on the Caliech campus November 2, 3 and 4.

FROM TIME TO TIME, people suggest to me that scientists ought to give more consideration to social problems – especially that they should be more responsible in considering the impact of science upon society. This same suggestion must he made to many other scientists, and it seems a be generally believed that if the scientists would only look at these very difficult social problems and not spend so much time fooling with the less vital scientific ones, great success would come of it.

It seems to me that we do think about these problems from time to time, but we don’t put full‑time effort on them – the reason being that we know we don’t have any magic formula for solving problems, that social problems are very much harder than scientific ones, and that we usually don’t get anywhere when we do think about them.

I believe that a scientist looking at non‑scientific problems is just as dumb as the next guy – and when he talks about a non‑scientific matter, he will sound as naive as anyone untrained in the matter. Since the question of the value of science is not a scientific subject, this talk is dedicated to proving my point – by example.

The first way in which science is of value is familiar to everyone. It is that scientific knowledge enables us to do all kinds of things and to make all kinds of things. Of course if we make good things, it is not only to the credit of science; it is also to the credit of the moral choice which led us to good work. Scientific knowledge is an enabling power to do either good or had‑hut it does not carry instructions on how to use it. Such power has evident value – even though the power may be negated by what one does.

I learned a way of expressing this common human problem on a trip to Honolulu. In a Buddhist temple there, the man in charge explained a little bit about the Buddhist religion for tourists, and then ended his talk by telling them he had something to say to them that they would never forget – and I have never forgotten it. It was a proverb of the Buddhist religion:

“To every man is given the key to the gates of heaven ; the same key opens the gates of hell.”

What then, is the value of the key to heaven? It is true that if we lack clear instructions that determine which is the gate to heaven and which the gate to hell, the key may be a dangerous object to use, but it obviously has value. How can we enter heaven without it?

The instructions, also, would be of no value without the key. So it is evident that, in spite of the fact that science could produce enormous horror in the world it is of value because it can produce something.

Another value of science is the fun called intellectual enjoyment which some people get from reading and learning and thinking about it, and which others get from working in it. This is a very real and important point and one which is not considered enough by those who tell us it is our social responsibility to reflect on the impact of science on society.

Is this mere personal enjoyment of value to society as a whole? No! But it is also a responsibility to consider the value of society itself. Is it, in the last analysis, to arrange things so that people can enjoy things? If so, the enjoyment of science is as important as anything else.

But I would like not to underestimate the value of the world view which is the result of scientific effort. We have been led to imagine all sorts of things infinitely more marvelous than the imaginings Of poets and dreamers of the past. It shows that the imagination of nature is far, far greater than the imagination of man. For instance, how much more remarkable it is for us all to be stuck – half of us upside down – by a mysterious attraction, to a spinning ball that has been swinging in space for billions of years, than to be carried on the back of an elephant supported on a tortoise swimming in a bottomless sea.

I have thought about these things so many times alone that I hope you will excuse me if I remind you of some thoughts that I am sure you have all had – or this type of thought – which no one could ever have had in the past, because people then didn’t have the information we have about the world today.

For instance, I stand at the seashore, alone, and start to think. There are the rushing waves . . . mountains of molecules, each stupidly minding its own business . . trillions apart . . . yet forming white surf in unison.

Ages on ages . . . before any eyes could see . . year after year . . . thunderously pounding the shore as now. For whom, for what? . . . on a dead planet, with no life to entertain.

Never at rest . . . tortured by energy . . . wasted prodigiously by the sun . . . poured into space. A mite makes the sea roar.

Deep in the sea, all molecules repeat the patterns of one another till complex new ones are formed. They make others like themselves . . . and a new dance starts.

Growing in size and complexity . . . living things, masses of atoms, DNA, protein dancing a pattern ever more intricate.

Out of the cradle onto the dry land here it is standing . . . atoms with consciousness . . . matter with curiosity.

Stands at the sea . . . wonders at wondering . . . I . . . a universe of atoms . . . an atom in the universe.

THE GRAND ADVENTURE

The same thrill, the same awe and mystery, come again and again when we look at any problem deeply enough. With more knowledge comes deeper, more wonderful mystery, luring one on to penetrate deeper still. Never concerned that the answer may prove disappointing, but with pleasure and confidence we turn over each new stone to find unimagined strangeness leading to more wonderful questions and mysteries – certainly a grand adventure!

It is true that few unscientific people have this type of religious experience. Our poets do not write about it; our artists do not try to portray this remarkable thing. I don’t know why. Is nobody inspired by our present picture of the universe? The value of science remains still unsung by singers, so you are reduced to hearing – not a song or poem, but an evening lecture about it. This is not yet a scientific age.

Perhaps one of the reasons is that you have to know how to read the music. For instance, the scientific article says, perhaps, something like this: “The radioactive phosphorous content of the cerebrum of the rat decreases to one‑half in a period of two weeks.” Now what does that mean?

It means that phosphorus that is in the brain of a rat (and also in mine, and yours is not the same phosphorus as it was two weeks ago, but that all of the atoms that are in the brain are being replaced, and the ones that were there before have gone away.

So what is this mind, what are these atoms with consciousness? Last week’s potatoes! That is what now can remember what was going on in my mind a year ago – a mind which has long ago been replaced.

That is what it means when one discovers how long it takes for the atoms of the brain to be replaced by other atoms, to note that the thing which I call my individuality is only a pattern or dance. The atoms come into my brain, dance a dance, then go out always new atoms but always doing the same dance, remembering what the dance was yesterday.

THE REMARKABLE IDEA

When we read about this in the newspaper, it says, “The scientist says that this discovery may have importance in the cure of cancer.” The paper is only interested in the use of the idea, not the idea itself. Hardly anyone can understand the importance of an idea, it is so remarkable. Except that, possibly, some children catch on. And when a child catches on to an idea like that, we have a scientist. These ideas do filter down (in spite of all the conversation about TV replacing thinking), and lots of kids get the spirit – and when they have the spirit you have a scientist. It’s too late for them to get the spirit when they are in our universities, so we must attempt to explain these ideas to children.

I would now like to turn to a third value that science has. It is a little more indirect, but not much. The scientist has a lot of experience with ignorance and doubt and uncertainty, and this experience is of very great importance, I think. When a scientist doesn’t know the answer to a problem, he is ignorant. When he has a hunch as to what the result is, he is uncertain. And when he is pretty darn sure of what the result is going to be, he is in some doubt. We have found it of paramount importance that in order to progress we must recognize the ignorance and leave room for doubt. Scientific knowledge is a body of statements of varying degrees of certainty – some most unsure, some nearly sure, noneabsolutely certain.

Now. we scientists are used to this, and we take it for granted that it is perfectly consistent to he unsure – that it is possible to live and not know. But I don’t know whether everyone realizes that this is true. Our freedom to doubt was born of a struggle against authority in the early days of science. It was a very deep and strong struggle. Permit us to question – to doubt, that’s all – not to be sure. And I think it is important that we do not forget the importance of this struggle and thus perhaps lose what we have gained. Here lies a responsibility to society.

We are all sad when we think of the wondrous potentialities human beings seem to have, as contrasted with their small accomplishments. Again and again people have thought that we could do much better. They of the past saw in the nightmare of their times a dream for the future. We, of their future, see that their dreams, in certain ways surpassed, have in many ways remained dreams. The hopes for the future today are, in good share, those of yesterday.

EDUCATION, FOR GOOD AND EVIL

Once some thought that the possibilities people had were not developed because most of these people were ignorant. With education universal, could all men be Voltaires? Bad can be taught at least as efficiently as good. Education is a strong force, but for either good or evil.

Communications between nations must promote understanding: so went another dream. But the machines of communication can be channeled or choked. What is communicated can be truth or lie. Communication is a strong force also, but for either good or bad.

The applied sciences should free men of material problems at least. Medicine controls diseases. And the record here seems all to the good. Yet there are men patiently working to create great plagues and poisons. They are to be used in warfare tomorrow.

Nearly everybody dislikes war. Our dream today is peace. In peace, man can develop best the enormous possibilities he seems to have. But maybe future men will find that peace, too, can be good and bad. Perhaps peaceful men will drink out of boredom. Then perhaps drink will become the great problem which seems to keep man from getting all he thinks he should out of his abilities.

Clearly, peace is a great force, as is sobriety, as are material power, communication, education, honesty and the ideals of many dreamers.

We have more of these forces to control than did the ancients. And maybe we are doing a little better than most of them could do. But what we ought to be able to do seems gigantic compared with our confused accomplishments,

Why is this? Why can’t we conquer ourselves?

Because we find that even great forces and abilities do not seem to carry with them clear instructions on how to use them. As an example, the great accumulation of understanding as to how the physical world behaves only convinces one that this behavior seems to have a kind of meaninglessness. The sciences do not directly teach good and bad.

Through all ages men have tried to fathom the meaning of life. They have realized that if some direction or meaning could be given to our actions, great human forces would be unleashed. So, very many answers have been given to the question of the meaning of it all, But they have all been of different sorts, and the proponents of one answer have looked with horror at the actions of the believers in another. Horror, because from a disagreeing point of view all the great potentialities of this race were being channeled into a false and confining blind alley. In fact, it is from the history of the enormous monstrosities created by false belief that philosophers have realized the apparently infinite and wondrous capacities of human beings. The dream is to find the open channel.

What, then, is the meaning of it all? What can we say to dispel the mystery of existence?

If we take everything into account, not only what the ancients knew, but all of what we know today that they didn’t know, then I think that we must frankly admit that we do not know.

This is not a new idea; this is the idea of the age of reason. This is the philosophy that guided the men who made the democracy that we live under. The idea that no one really knew how to run a government led to the idea that we should arrange a system by which new ideas could be developed, tried out, tossed out, more new ideas brought in; a trial and error system. This method was a result of the fact that science was already showing itself to be a successful venture at the end of the 18th century. Even then it was clear to socially‑minded people that the openness of the possibilities was an opportunity, and it that doubt and discussion were essential to progress into the unknown. If we want to solve a problem that we have never solved before, we must leave the door to the unknown ajar.

OUR RESPONSIBILITY, AS SCIENTISTS

We are at the very beginning of time for the human race. It is not unreasonable that we grapple with problems. There are tens of thousands of years in the future. Our responsibility is to do what we can, learn what we can, improve the solutions and pass them on. It is our responsibility to leave the men of the future a free hand. In the impetuous youth of humanity, we can make grave errors that can stunt our grow for a long time. This we will do if we say we have the answers now, so young and ignorant; if we suppress all discussion, all criticism, saying, “This is it, boys, man is saved!” and thus doom man for a long time to the chains of authority, confined to the limits of our present imagination. It has been done so man lines before.

It is our responsibility as scientists, knowing the great progress and great value of a satisfactory philosophy of ignorance, the great progress that is the fruit of freedom of thought, to proclaim the value of this freedom, to teach how doubt is not to be feared but welcomed and discussed, and to demand this freedom as our duty to all coming generations.

January 21, 2017

A Wake up call from the illusion of Democracy? – Book Review

“If you want to feel ten feet tall and as though you could run a hundred miles without stopping, hate beats pure cocaine any day. Hitler resurrected a beaten, bankrupt, half-starved nation with hatred and nothing more. Imagine that.”

– Kurt Vonnegut, “If This isn’t Nice, What is?”

In this work, the author offers a very unbiased account on the emergent new-age leaders of two largest democracies. The kind of new-age politicians (using the word ‘politicians’ can be preferred over ‘leaders’) who have been dominating the world lately. POTUS Trump. GBR Prime Minister Theresa May. Emerging Right wing party leaders of GER, FRA, NED who recently gathered for Trump victory and discussed about affecting the EU’s economy. The kind of leaders who spent $570 million on anti-immigration across the European nations since the fall of Berlin Wall.

Narendra Damodardas Modi and Recep Tayyip Erdogan @G20 Summit 2015

Getting back to the content, the structure involved the bottom up approach starting from the circumstances which these strongmen utilized for the beginning their political career to the point of reaching the level of narcissistic leader which mammoth supporters denouncing pluralism and biased cultural oppression. Political Lobbying, Religious Chauvinism, Jingoism, Semi Educated political and economic views, Victimized Scholars and freethinkers, Pride, Prejudices and Subjudices are some of the common feature of the problems discussed through the work.

Turkey part holds the major portion of the work starting from the leader founding the nation with western philosophized constitution to it’s recent failed coup against the present leader, is worth told by the author as the roots are felt essential in the later events. Though the Political history might seem complex, the author did the good part explaining precisely and briefly. Regarding Erdogan, the author did his best in showing the two-face nature of the Prime Minister cum President who has been controlling the nation since 2003. I felt the meticulous work more on this part where various aspects are discussed in relation to the Kurdish, ISIS, Greece and European Union.

Unlike Turkey, India’s part start right from a specific Party which is currently under administration, The Modi’s BJP Party. Author used unbiased words avoiding sensitive elements directly most of the time so that even if an ardent follower of these politicians could get less offended. Regarding Modi, the work covers much on the social-cultural oppression of the minorities and their interviews from accounts that happened from 90s to present; the havoc propagandized by the Political side of the person’s Party. What this part lacked is the account didn’t explain much on the economic path which also has been deflating compared with the previous administration even before the recent demonetization which is too soon to be recorded, analyzed and included by the author. The age of majoritarian politics was here to stay, and all Modi had to do was stay silent.

Overall, A Question of Order speculates over the possibilities of the persistence of a long-held belief system called Democracy. Almost 75% of the world democracies are being flawed. Burke’s discomfort with and opposition to the French Revolution is not surprising. The Revolution was an abrupt breach with the past in every conceivable manner; this angered and anguished the father of conservatism. He wrote in the Reflections on the Revolution in France,

“I should therefore suspend my congratulations on the new liberty of France, until I was informed how it had been combined with government; with public force; with the discipline and obedience of armies; with the collection of an effective and well-distributed revenue; with morality and religion; with the solidity of property; with peace and order; with civil and social manners. All these (in their way) are good things too; and, without them, liberty is not a benefit whilst it lasts, and is not likely to continue long.”

His words proved to be prophetic, as Revolution in France soon started devouring its own children; there was a reign of terror, mass slaughter (including that of a large number of innocent people), wars, destruction and devastation in entire Europe. And now, looking at our current geo-political scenario may again possibly (not probably) lead us go back to those good old days.

Events after the finalization of the book content:

1. Pro-Jallikattu Protests which has been going on for the past 10 days, officially came to a halt today revolved over the conspiracy that Modi is trying the oppress the cultural minority to possess the political administration due recent demise of the political giant in Tamilnadu, Southern State in India.

2. The move of Demonetization in the past November by Prime Minister Modi, was heavily criticized as poorly planned and unfair, and was met with resentment, protests and economic downfall.

3. The Struggle indicated in the book by Erdogan in switching the prime powers from Prime Minister to President since he switched the role in 2014, is successfully done the previous day of writing this review. It works more like USA from now on.

A Wake up call from the illusion of Democracy?

Book: A Question of Order: India, Turkey and the Return of Strongmen

.

The author Basharat Peer was born in the vulnerable militarized zone of Kashmir which is familiar for it’s conflict between India and Pakistan, later went on study Journalism at Columbia University.

Review posted – January 23, 2017

Publication date – March 24, 2017

I thank Netgalley, author and Columbia Global Reports, Columbia University for this great opportunity. I really hope to read other books from the series.

January 18, 2017

Confessions of a Patriot

“Sare Jahan Se Acha Hindusthan Hamara” – Better than the entire world is our Undivided India.

The cliché about India is that “it is the world’s largest democracy”. Living these days under the illusion of democracy, i look upon these words skeptically. For the past few years, I’ve been watching the happenings of USA too closely that i forgot to look those dirt on my own place. Various issues like Cultural oppression. Political Lobbying, Islamophobia, Xenophobia, Victimizing the freethinkers and Scholars, Officers with implicit biases treating people are some of the few.

Here’s a quick prologue to Outsiders

In 1989, Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP – Indian People’s Party) took over the concept of Hindutva [Seeking to establish the Hindu way of life] as its ideology. It has made several milestones long since its inception using its crippled ideology. Demolishing a medieval mosque in a place where God Rama was presumably born and built a temple for him over it. Since the majority of the nation got swayed by them using organized planning of lobbying and influencing the use of the hatred on other ethnic groups in the critical states, Narendra Damodardas Modi took hold the most powerful position in the country (2014) and started helping build up the economic growth (till 2015) very rigorously unlike many previous prime ministers (Regarding the demonetization which happened last November, I’m so much baffled by the biased media and scholars of left-right wing spokespersons yet it’s troubles a lot of muggles than wealthy) but he undermined the importance of civil liberties and protections from the tyranny of the majority. And an increasing number of illiberal democracy is unabashedly being led by this strongman.

Taking the cases of Rohith Vemula and Jallikattu Issue as example the government is either influencing the segregation and the feeling of anti-national notions directly or indirectly through the ruling party’s base organization Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) – National Volunteer Organization and its student wing Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad (ABVP) – All Indian Student Council.

Recently Supreme Court did its part in preserving the feeling of nationalism in people making it mandatory playing of the national anthem before movies in theaters. But instead of enforced nationalism we need to create an environment in which the feeling of nationalism comes from within through visionary leaders, good governance and an inclusive harmonious environment in the country. We need to evolve into a country that elicits nationalism and feeling of love from everyone residing in it. Why only Indian citizens need to be nationalistic their motherland, other non-citizens should also have such feeling for India if they reside here. That is the kind of nationalistic feeling or belonging that needs to be promoted¹.

In the village of Bishara after the 2015 dadri mob lynching (refers to lynching in which a mob of chauvinistic Hindu people attacked a Muslim family presuming that they had cow meat ignoring the ban for dinner, on the night of 28 september 2015 in bishara village of Uttar Pradesh but turned out they hadn’t and known too late to bring back the senior of the family), most of the Muslims remained in the village as the chances of surviving and affording to buy a house anywhere is almost difficult. One older man said “He, we have our homes. And the village is quiet now. Things are better.“ A young man, who had wrapped himself in a blanket and sat on the floor, raising his head. “There’s one difference in living here now”, he added “in the old days, if I had an argument I would retort. Now I bow my head and keep walking” indicating the Modi administration². Who cares about economy if one couldn’t able to live happily in a place where he’s been living his entire life.

On accounting the countries in which citizens live peacefully and does the most good to the rest of the world, Kenya lies in top 30 position while countries like China and Russia and India(ranked 124 of 163 as per 2016 for equality and prosperity), which is down in the same part of the Good Country index. And that tell us one very, very insightful thing. This ain’t about Money. This is about attitude and culture. This is about a government caring of its people and people caring about the rest of the world and possessing imagination and courage to think outwards instead of only thinking selfishly. Who are to think about the rest of the world when we can’t even think selfishly as one people belonging to this country. Well, I don’t want to live in the fast growing or competitive country. I want to live in a good country and I hope that you do too.

Thanking for reading and may god bless you all (In case you believe.)

January 14, 2017

“Neil deGrasse Tyson The Inexplicable Universe Unsolved Mysteries” on YouTube!

Things got well for me knowing and understanding things better at an elementary level. Wonderful storyteller defending Science, glad we have a Neil deGrasse Tyson these days. Everything that only a few know of and ought to be known by the most of us, from the quantum perspective to the mammoth cosmic perspective of galaxies “in simple words” (No wonder toddlers could be smarter than adults) and let those understanding and perspective impact your life in a profound way!

January 9, 2017

To Be Scientist Than Atheist – Richard Dawkins

I happen to see a blog on “Podcasts and why you should listen to them” recently which reflected my life partially made me take time to look back. I suggest you guys to try reading that as well.

Things went better after my headphones are used not only to listen Eminem Rap and Linkin Park songs but also to Podcasts featuring many Scientific People influencing every culture more than ever which is worth notable. Things started well with TED Talks, getting familiar with some interesting people and their ideas and some of their books and Podcasts. A few hours ago, I went out with the headphones for night stroll along the streets near me apartment. It was pretty dark and cold. Could see many constellations and planets clearly because of winter. After the best known Astrophysicist and Educator Neil’s StarTalk Radio being my favorite, the next is a Physicist’s one on BBC4 named Life Scientific. It was recorded years ago, 2011 or 2012 I guess, with an evolutionary biologist but rather known widely for his atheistic notions personally. I have never read his books before but I know he’s one of the critical thinkers alive and watched his debate videos (a lot) against indoctrination and creationist education. I love his answer for a girl’s question “What of you’re wrong reg God?”

[image error]

I knew a lot about Physics and Astronomy when compared to Biology and Evolution. The Interview was mainly on his two notable works. One on his research ideas of evolutionary Biology, The Selfish Gene and the other being a refuter on the concept of a supernatural agent named The God Delusion.

He insisted on people often confusing Embryonic Science with Evolution with context to Genes. I do felt the need to feel things from biological perspective as well. I’m too much used up by The Cosmic Perspective (Check out the essay when you get time. Yeah it’s pretty lengthy!)