Paula Pederson's Blog

January 24, 2019

Ukrainian Immigrant Homesteaders to Canada

A Sod Dwelling

In 1898, a Ukrainian Lord in the municipality of Rohizna, donated passage to Canada for his horse groomer’s family. The Canadian government welcomed struggling Eastern Europeans as homesteaders who would settle Alberta’s fertile but icy windswept plains.

Customs officials unfamiliar with the Cyrillic alphabet assigned my mother’s grandparents the anglicized name of Tokaruk and her newly wed parents the name of Huculak. The family arrived with the earliest pioneers — former serfs who chose forested land that had to be cleared before they could begin to farm their own land.

The Canadian government offered them a quarter (160 acres) of land that had to be settled in order to obtain their title. As the family crossed central Canada on the newly completed Canadian Pacific Railroad, they marveled as they crossed thousands of miles of forests and thought of how wealthy they would be in this land of trees.

On a tour, our guide leads us to a burdei or buda — a sod hut. Dug into the ground and covered in thatch, it sheltered the pioneers until they could clear their heavily forested land. They crowded into the hut (smaller than the one in the above photo), and breathed the damp earth smell. Entire families huddled on benches that edged the dark and claustrophobic burdeis, sometimes for days, while winter raged and temperatures plunged to-40° on the Alberta plains. A desolate silence of boundless cold and dead whiteness brought time to a standstill as wind blew the churning snow into drifts heavy enough to warm the burdeis.

The family crowded into a burdei their first winter, but abandoned it in spring when it became a dripping, covered pond. Their only choice was to move out under the stars where they contended with mosquitos, mud, bears, and howling wolves at night. In general, women cleared the land and planted seeds. To earn enough to survive, many men left home for months at a time to work on the railroads.

My mother’s parents filed for title to their land in 1898, the same year my Danish immigrant father Hans Pederson returned to Seattle after a year as a Yukon prospector on the Klondike Gold Rush. He began a building career that by the time of the Depression brought him success as one of Washington’s greatest contractors.

My Canadian homesteading forebears managed their house and barn relatively quickly, but it took five years of backbreaking labor with only a pickaxe before they cleared the ten acres of heavily forested land and obtained their title. In 1916 my mother, Domka Huchulak, fourth of seven siblings, became the first member of her family to attend school since the Canadian government offered schooling only to English speaking children.

© 2018 Mysterious Builder of Seattle Landmarks, Searching for My Father by Paula Pederson

January 17, 2019

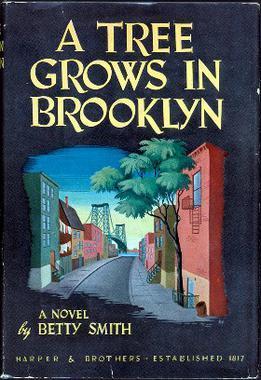

The Immigrant Experience in A Tree Grows in Brooklyn

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

A book that has stayed with me through the years is “A Tree Grows in Brooklyn,” by Betty Smith, an author who would have been my mother’s contemporary. I too grew up in New York, but in Manhattan, not Brooklyn, just a few years after the childhood of Francie Nolan, heroine of Betty Smith’s novel. My childhood and adolescent years paralleled Francie’s coming of age. But my affluent East Side neighborhood and sheltered private schooling kept me riveted on Francie’s life, so diametrically opposed to mine.

We meet the Nolans, Francie’s early-20-thCentury urban family, in their Brooklyn tenement when Francie is eleven: her mother, a scrubwoman, her father, an alcoholic singing waiter. Francie and her brother Neely, have sold their day’s collection of junk: rags, metal, paper and scrap, and given their mother Katie, the few pennies that they have earned. Katie feeds her family the dinner she has concocted based on stale bread.

Katie is a second-generation member of Austrian immigrants who hope to rise above poverty through their four children. Since her parents never learned to speak English, Katie’s eldest sister never went to school and her younger sisters did only for a few years. Katie’s mother tells her to be sure that her own children learn to speak English.

Katie’s ambition is for Francie and her brother Neely to complete college, or at least high school. To enhance their language skills Katie has provided them with the Bible, and the complete works of Shakespeare. The children study these books backwards and forwards.

When their father dies, only Neely can afford high school. With her eighth grade diploma determined Francie works her way through progressively challenging jobs and at 17 is accepted by the University of Michigan when book ends.

Recently reading the book again, I was struck by the parallels with my own parents’ immigration experience. Hans Pederson, my Danish father, attended a laborers’ school twice a week from the ages of 7-14. He emigrated to Seattle at 20 then survived a year in the Yukon as a prospector during the Klondike Gold Rush of 1898. The skills he mastered launched him as one of Seattle’s largest pioneer contractors until the Depression mothballed building and other commerce.

My mother, born just a few years after author Betty Smith, was the granddaughter of a Ukrainian horse groomer who crossed North America on the Canadian Pacific Railroad in 1898. Speaking Ukrainian her family remained close as they homesteaded their Alberta farms. My mother, a brave member of the third generation was the fourth of seven children. A pioneer as well, she was the first in her family who dared to attend school since the Canadian government in 1916 offered schooling only to English-speaking children.

It often takes determined immigrants three generations to find their place in a new society

January 10, 2019

My World War II Childhood

Ready for the New York City Easter Parade

I grew up in New York City during World War II sharing only the minor inconveniences of my fellow Americans. My job was to pull down the blackout shades at night so that the Nazis, Japs, or Italians wouldn’t bomb us. Sure, our family had food and gas rationing and there was no room for a victory garden on our sooty windowsills, but buses, subways, and taxis took us anywhere we needed to go.

We mostly walked. During those pre-mall days, on weekends my friends and I walked 40 blocks down Fifth Avenue, making a stop at Hamburger Heaven for lunch. Next, telling ourselves we were way too old, we’d stop to check out the amazing toys at F.A.O. Schwartz. We’d move on down Fifth to the department stores, Best & Co. Wanamakers, and Lord & Taylor. Somehow I remember that the main attraction at these stores was the Shoe Department where we’d line up to check the bones of our feet under the X-Ray machines, while being studiously avoided by the retail clerks.

Our mothers made sure we were properly dressed. Especially for The Easter Parade We always wore hats and gloves for our promenades down Fifth Avenue.

How fortunate I was to enjoy the education, culture, and infinite variety of the nation’s largest city. We left when I was 15, but I treasure my childhood memories.

When our daughters were 11 and 7 in 1969 and we lived in a small Pennsylvania town, their father took them to New York’s Lincoln Center. I hoped they’d also have time for the Metropolitan Museum of Art, a Broadway play, and maybe a stroll down Fifth Avenue. I made sure they were dressed properly in their hats, gloves, and black patent leather Mary Jane shoes.

“Mom, you are so out of it,” they wailed as they reached home and climbed out of the car. “We were the only people in the entire city who weren’t wearing jeans and sweatshirts.”

I’m well aware that I’m an anachronism to my children— even more to my grandchildren. But if my granddaughters make it to the Big Apple any time soon, I wonder if their parents will insist that proper attire mandates that they be clad in ripped jeans and sweatshirts with holes.

January 3, 2019

Seattle Saves Its Legacy

Seattle’s Roy Vue Apartments and Courtyard

Seattle’s Roy Vue Apartments, a reasonably priced complex, contains 31 apartments in Seattle’s desirable Capitol Hill neighborhood. Recently awarded Landmark status by three Seattle preservation boards, the building was constructed in 1924 by my father, early 20th century builder, Hans Pederson, a Danish immigrant.

Actually, the city’s vigilant Landmarks Preservation Board pointed out that landmark status saved only the exterior of the Roy Vue and its charming courtyard. The building’s current owner had planned to reconfigure the entire property by turning the 31 existing apartments and its grounds into 147 expensive micro-units.

Seattle’s Capitol Hill neighborhood is a microcosm of the dizzying pace of change taking place in growing cities today as density increases and open space is filled. Where to park the cars? Well, Capitol Hill has recently started charging for evening as well as street side daytime parking.

Our world is so filled with problems that choosing a focus for 2019 is not easy. As the new year begins, saving homes and neighborhoods may not be at the top of your list. It reached the top of mine in 1960 when passenger train service ended in my home town of Portland Maine. All of us had taken Union Station for granted. Built in the style of a French chateau in 1888, the building was a city treasure. Well, developers razed the station in 1961 to make way for a gaudy garish strip mall that still festers like an open wound. Portland’s historical restoration movement roared into action like a bullet train after they destroyed Union Station .

Union Station Portland, Maine courtesy Wikimedia Commons

So pay attention folks, if old homes and landmarks are part of your legacy.

Once they’re gone, they’re gone.

December 8, 2018

Hans Pederson’s Seattle Legacy

Roy Vue Apartments 1924. Charles Lyman Haynes, architect. contractor, Hans Pederson

Born in the village of Stenstrup Denmark in 1864, my father. Hans Pederson, attended a laborer’s school twice a week from the ages of seven to fourteen. At twenty he worked his way West to Seattle as an immigrant on the Northern Pacific Railroad.

Although he found no Yukon gold during the Klondike Gold Rush of 1898, the technical skills he acquired as a prospector served him well as a Seattle contractor. Seattle and Puget Sound bustled with the largest population growth in history during the first third of the 20th Century. The area continued to do well until the 1929 depression. Pederson’s projects number in the hundreds over the course of thirty years and range from nearly forty apartment houses, to sidewalk and road paving project, to skyscrapers and private homes.

“No project was too great or small for Pederson.” A March 27, 1931 article in the Christian Science Monitor noted. His credo was to take any job to keep crew employed and paid. His most noted projects are listed below.*

Seattle’s Landmark Preservation Board recently granted Landmark status to the downtown Roy Vue Apartments after nomination by Historic Seattle and the Capitol Hill Historical Society. How fortunate that this neighborhood gem has been spared the wrecking ball in the name of “progress.” You can see why the residents don’t move.

Space Needle and mountain view

gardens

*Among Pederson’s most notable projects are the Arctic Building (1916, City of Seattle Landmark), Seabord Building (1909, City of Seattle Landmark) Washington Hall (1908,City of Seattle Landmark), Milwaukee Hotel (1911, contributing resource – Seattle Chinatown National register Historic District), St. Regis Hotel (1909) the Rex Theatre (1915, demolished) Alhambra Theatre (1909, extensively altered), Blue Mouse Theatre (ca. 1920, demolished), the 15th avenue NW (Ballard) bridge and viaduct (1917), Ford Assembly Plant in Seattle (1913, City of Seattle Landmark), Temple of Justice in Olympia, Terminal Sales Building (1925, City of Seattle Landmark) and the King County Courthouse, 1930, King County Landmark). He also constructed many country roads throughout the state of Washington and worked on reclamation projects as well.

December 6, 2018

Hans Pederson’s seventh Seattle Landmark

Washington Hall, Victor Voorhees architect, Hans Pederson Contractor Courtesy Wikimedia Creative Commons

After decades of believing that Danish immigrant Hans Pederson left us penniless, I uncover the truth about my father’s wealth and prolific contributions to Seattle. I discover my mysterious father’s boom to bust life in the early 1900s as I grapple with family secrets and deception in my recently published memoir, Mysterious Builder of Seattle Landmarks Searching for My Father.

100 years later, Hans Pederson’s legacy continues to grow. The Roy Vue apartments have just been designated the seventh Seattle Landmarks building constructed by Hans Pederson. His last-named landmark was Washington Hall, the 1908 building that continues to be a melting pot a century later. For 100 years the building sheltered immigrants from Denmark, Mexico, Puerto Rico and Brazil. Its stage and dance hall brought such outstanding performers as Marcus Garvey, W.E.B. Du Bois, Duke Ellington, Billie Holiday, and Jimi Hendrix.

Historic Seattle purchased Washington Hall in 2009. After raising $15,000,000 to restore the building, it reopened in 2016 jointly hosted by anchor partners 206 Zulu celebrating Hip Hop, HIDMO relaunching community space, and Voices Rising an LGBT musical group of color.

Today’s headlong rush to obliterate the old ignores the contributions of our past. Historic societies keep our heritage alive by preserving both the wisdom of bygone days and the changing contemporary culture.

November 29, 2018

Writer Maya Angelou

Maya Angelou reciting her poem, “On the Pulse of Morning” at President Bill Clinton’s Inauguration, January 20, 1993, courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Wrier Maya Angelou, 1928-2014, possibly best known for her book, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings,” was an American poet, singer, and memoirist. After a tumultuous childhood she appeared in Porgy and Bess, learned the language of every country she visited, and received over 30 honorary degrees from universities all over the world.

Active in the American Civil Rights movement, she was a friend of James Baldwin, Martin Luther King, Malcolm X , and Oprah Winfrey.

Wikipedia quotes the Guardian writer Gary Younge in 2009: “To know her life story is to simultaneously wonder what on earth you have been doing with your own life and feel glad that you didn’t have to go through half the things she has.”

We often meet more people than usual during the holiday season. These occasions bring to mind one of Maya Angelou’s notable quotes:

“I’ve learned that people will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.”

November 15, 2018

Depression Years, Seattle and Asheville

Montreal Soup Kitchen 1931 Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

For most of my life I searched for information about my Danish immigrant father, a prominent early 20th Century Seattle Contractor. I titled my memoir “The Mysterious Builder of Seattle Landmarks: Searching for My Father.” The mystery was that my mother never told me about him. It took me most of my life to learn why. One reason was their 42-year age difference. My 25-year old mother, a Ukrainian Canadian immigrant, was Hans Pederson’s nurse. His business ruined by the Depression, he suffered through the first month of my life in 1933 until felled by a stroke, he died at 69.

My research taught me about the lives of my parents and what they faced during the Depression, I stopped blaming my mother for what she couldn’t reveal. As her cousin said, “It was a desperate time.” The above photo of a Montreal soup kitchen says it all.

The Biltmore, Asheville, NC courtesy Wikimedia creative Commons Attribution 4.0

Denise Kiernan’s ” The Last Castle, The Epic Story of Love, Loss, and American Royalty in the Nation’s Largest Home,” tells the story of Cornelius Vanderbilt who made his fortune during America’s 19th Century Gilded Age. His son George took his share of the family fortune to Asheville, North Carolina where in 1898 he completed construction of the Biltmore, a home of vast proportions. Set in the Pisgah Forest in the Blue Ridge Mountains, the Pisgah later became America’s first National Forest. Noted landscape architect Frederick Law Olmstead designed the grounds. The Biltmore was America’s answer to European royalty.

The home spawned the development of the city of Asheville. The Vanderbilts built schools for children of the people who worked for the Biltmore Estates Industries developed to serve the Vanderbilts along with the royalty, millionaires, presidents artists, authors and other luminaries who passes through the Biltmore’s doors.

After the 1929 stock market crash, Cornelia, granddaughter of Cornelius Vanderbilt, found the Biltmore too expensive to maintain. She sold the forest, cut funding for the village of Asheville as well as for the Biltmore Industries. Cornelia ultimately opened the home to the public to traipse through and gawk at the grandeur.

Today Asheville is thriving and the Biltmore remains a popular tourist destination. In 2018 you can buy a ticket and a self-guided tour for $79. You can buy books showing Christmas trees and decorations, and others showing the gardens in bloom.

Even though the Biltmore fell on hard times during the Depression like everyone else, the Vanderbilt’s did provide a cushion from ruin for those who had served them.

November 8, 2018

Stranded by the Railroad–2

(http://paula.pederson.files.wordpress.com/2014/07/train.jpg

continued from November 2

We were on the way to San Diego to visit our granddaughter Sarah. After I started down the ramp when the conductor told me I could dump my trash at the railroad station, he turned and boarded the train as it was about to pull away. Irate, I headed for the ticket office to report the clueless conductor. Fortunately the clerk had a record of our purchase and gave me a new ticket. Ranting away, I told my tale to the woman in line behind me.

“I agree.” she said. “We’re from Texas, and those conductors. They do not help you.” She opened her purse and pulled out her wallet. “Here’s $20.”

“Oh no, no, no,” I demurred, raising my palm.

‘Yes, take it. I heard her say you’d be here for three hours.”

“Oh thanks anyway. I’ll survive.” I turned resolutely , walked toward a bench, and sat down.” In deference to the coming Christmas season, a few chewed-up looking silvery garlands had been draped along the walls.

I considered my folly in dashing off to a strange city with no money or ID. On this breezy Sunday afternoon, I’d get cold if I went out for a walk. Besides, by now my husband, in the midst of solving the Sunday crossword puzzle, had surely noticed that I wasn’t sitting beside him, so he’d be calling me on the cell phone any minute.

My stomach rumbled. I hadn’t eaten. I went back to the kind lady from Texas. “You know, I might take that $20. If you’ll give me your name and address, I’ll mail you a check when I get my purse back.”

She waved the bill at me. “Take it. Just pass it on to the next stranded traveler.”

I bought a drink from the vending machine and waited for my husband to call.

But I had forgotten about Mike, the crossword puzzle fanatic. It took him nearly an hour to realize that while my purse sat on the seat beside him, I did not. He searched the train in vain, then asked to borrow a fellow passenger’s cell phone. Remembering our number, he punched it in and barked, “Where are you?”

“In Anaheim.”

Sparks flew later, but how fortunate I was that a kind traveler took pity on an old white-haired woman instead of writing me off as a predator or thief. I’ve since passed that twenty on to both other stranded travelers and also to a newly arrived U.S immigrant.

November 1, 2018

Stranded by the Railroad – 1

(http://paula.pederson.files.wordpress.com/2014/07/train.jpg)

A visit with our daughter in Oxnard, California included a whale watch around the wild and craggy Channel Islands. Afterwards, we decided to follow-up with a trip to see our San Diego granddaughter.

My husband bought the Los Angeles Times specifically to solve the Sunday crossword puzzle on the train ride south. So when the loudspeaker later blared a request urging all passengers to dispose of their trash, I rustled up the news sections, circulars and coupons, and searched unsuccessfully for a receptacle.

“Where can I dump these papers?” I asked the conductor as the train pulled to a stop at Disney World’s Anaheim station.

He pointed to the foot of the ramp. “Right in that barrel.”

“Is there time?” I asked.

“Sure,” he said, helping an elderly passenger to board.

I started down the ramp with the newspapers and looked up just as a hissing sound told me the train was pulling out of the station. I realized I had left my purse on the seat next to my husband. It contained my credit cards, checkbook, and cash. Still, the comforting bulge in my pocket told me that I was not alone. I had brought the cell phone.

What could I do but wait three hours for the next train? I called our granddaughter and sat down to wait. Mike would find a way to call me even though I had the cell phone.

What a nuisance! Still, I soon realized how fortunate I was. My husband had just sped by on one train and our granddaughter would meet me at the next one. It could be a lot worse.

Have you ever been stranded with no money or ID?