Bernie MacKinnon's Blog, page 2

March 3, 2015

Nerding Out With Chester A.

Tomorrow marks the 150th anniversary of Lincoln's transcendent Second Inaugural Address. I've just read an absorbing series of articles in Smithsonian magazine about the Lincoln assassination and things related. But the leader I'm writing about here is not Lincoln and not what you'd call a household name.

This past Presidents Day (Feb. 16) brought to mind an NPR-sponsored contest I entered in the fall of 2012, "3-Minute Fiction: Pick A President." Contestants were told to submit a 600-word entry—about 3 minutes' reading time—focusing on any U.S. President, even a fictitious one. Over the weeks they read some of the entries on-air or posted them on the NPR site and I enjoyed all of them. The winner in the end was very good and quite original, featuring a man whose dementia-plagued father believed that Spiro Agnew had succeeded Nixon as President.

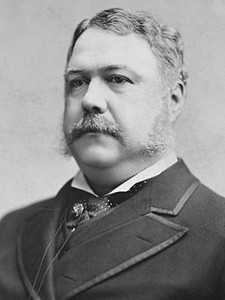

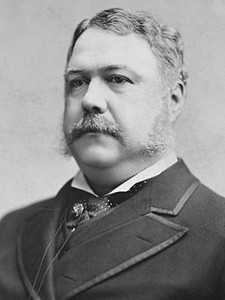

My submission was probably doomed to obscurity when I decided that it should be about our 21st President, Chester Alan Arthur. Why did I do this? Why did I pick my man from the gray middle of the pack—a virtual guarantee that it would be like throwing a jellybean into the Grand Canyon and waiting for an echo? The answer is straight from History Nerd Central: I am a champion of Chester A. I think he was a decent guy who made the best of a daunting situation. And I think he belongs farther up the rankings than historians often place him.

Chester A. Arthur, 21st President

of the United States.

(Courtesy: Library of Congress)

In the giant shadow of Abraham Lincoln, in a landscape gibbering with the ghosts of over 700,000 dead—and with the failure of Reconstruction, the maw of Jim Crow opening wide—post-Civil War politics seemed overpopulated with men who were bitter, vengeful, venal, corrupt and small. As far as Presidents go, many of us tend to think of the 36 years between Lincoln and the bright comet of Teddy Roosevelt as a kind of trough. Given this, it is surprising to actually look at who got into the Executive Mansion. Apart from Andrew Johnson and Benjamin Harrison—consistently rated as bottom-feeders—the United States was lucky to have these men available for the office. A few like Arthur were natural administrators; others like Ulysses S. Grant were not, but at least showed themselves to be fundamentally good and honest. It could definitely have been worse, as Johnson and Harrison abundantly proved.

Arthur was born in Fairfield, Vermont in 1829. His Irish-born father was a teacher-turned-minister and bedrock Abolitionist. Arthur (whose family always called him "Alan") started out as a teacher but ultimately switched to the law and New York City. Upon his admission to the bar, he joined the firm of the Abolitionist lawyer and family friend Erastus T. Culver, who then made him a partner. He lost no time distinguishing himself, helping to win the Lemmon v. New York decision, which established that any slave transported to New York State was automatically free.

Soon afterward, in 1854, Arthur served as lead attorney for Elizabeth Jennings Graham, a black schoolteacher and church organist. Late for service one Sunday, Graham had boarded a New York City streetcar which turned out to be whites-only. The conductor ordered her off but she insisted on her right to ride. Only after putting up an impressive physical fight with the conductor and a policeman before a hostile crowd was she forced off the car. It should perhaps have been clear right then that they had messed with the wrong church lady—but it definitely became so when Arthur took up her case. (Something else that might have made them think twice: Graham was the daughter of wealthy clothing store owner Thomas L. Jennings, founder of the Abyssinian Baptist Church and also the Legal Rights Association, which targeted racist statutes.) The next year—a full century before Rosa Parks—Arthur won Graham's suit against the conductor, the driver and the Third Avenue Railroad Company, which then had to desegregate its streetcars. Thanks in large part to the decision, all of NYC's public transit services were desegregated by the end of the Civil War. Elizabeth Graham went on to found the city's first kindergarten for black children.

Elizabeth Jennings Graham (1827-1901), civil

rights heroine and successful Arthur client.

(Courtesy: Kansas Historical Foundation)

By the time of the Civil War, Arthur had his own law practice, was deeply involved in Republican politics and married to the Virginia belle Ellen "Nell" Herndon, daughter of naval officer and explorer William Lewis Herndon (who was lost in the sinking of the SS Central America in 1857.) In 1861 the governor of New York assigned Arthur to the state's quartermaster department with the rank of brigadier general. He was so effective at housing and equipping the new troops that deluged NYC that he was soon promoted to inspector general and then quartermaster. He would have gone to the front as a regimental colonel if not for the governor's personal plea for him to maintain his home-front role. Yet that role was a political appointment and when the Democrats took over state government in 1863, Arthur lost his post.

Soon after this, he and Nell suffered the death of their three-year-old son William from illness. Nell gave birth to another son, Chester Alan Jr., the following year. In their ongoing grief over William, they heaped indulgence on young Chester, who grew up to be a rich, idle, attention-loving playboy. In 1871 they had a daughter, Ellen, who would lead a much lower-profile life. That same year saw Arthur named Collector of the Port of New York—a federal appointment and a highly lucrative one, typifying the spoils system and its routine rewards for political loyalty. It was a corrupt system, though then fully legal and Arthur personally quite honest. By the mid-1870's, however, the fever for civil service reform threatened to split the Republicans between the reform-minded "Half-Breeds" and the more traditional and complacent "Stalwarts," with the political machine of Senator Roscoe Conkling (Arthur's friend and patron) embodying the latter. The conflict resulted in President Rutherford B. Hayes sacking Arthur in 1878, an experience that left Arthur feeling branded as corrupt.

Arthur's ever-increasing work for the Conkling machine led to late nights and long absences, which strained his marriage. He was away in Albany in January 1880 when Nell died of pneumonia at age 42, causing him a sense of guilt that never quite abated. Within a year of this, he was catapulted to the Vice Presidency of the United States. The tumultuous 1880 Republican convention ended up nominating the "dark horse" (compromise, unforeseen) candidate James A. Garfield of Ohio for President. A champion of the Half-Breed faction, Garfield sought to mend the party split by choosing the Stalwart Arthur as his running mate. Arthur readily accepted the offer despite Conkling's urging that he not. His role in the election proved crucial, as the Republicans won by a wafer-thin 9,070 in the popular vote.

Ellen "Nell" Herndon Arthur (1837-1880), wife of Chester

A. Arthur. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

Arthur and Garfield immediately became estranged, however, over the latter's resistance to appointing Stalwarts to important posts. Arthur was in Albany on July 2, 1881, when he heard that Garfield had been shot and grievously wounded on a Washington railroad platform. Most unfortunately for Arthur, the assassin Charles J. Guiteau had declared on the spot, "I am a Stalwart, and Arthur will be President!" Never mind that Guiteau (often described as "a disappointed office-seeker") would make Booth and Oswald look like poster boys for mental health—the statement stoked public mistrust of Arthur, due to his background in urban machine politics.

Over the terrible eleven weeks that it took President Garfield to die, Constitutional constraints and Arthur's reluctance to seem presumptuous re: presidential authority (he stayed the whole time in NYC) created a power vacuum, ending only with Garfield's death on Sept. 19. And here I must say—the full tragedy of James Garfield's murder is lost on us today. He was smart, honest, gutsy, highly competent and a talented orator. Though President for only six and half months, the final two and a half spent bedridden and in pain, he had shown himself to be a quality leader, one who belonged in high office. As a for-instance, his feeling for the plight of African Americans was genuine, his intentions for them heartfelt without being especially naive; he in fact appointed a number of them to prominent posts, at a time when it was increasingly risky to do so. The tragedy would have been compounded had an Andrew Johnson been waiting in the wings to assume power. Luckily for all of us, though, it was Chester A. Arthur.

Widespread skepticism greeted Arthur's swearing-in. He came to the office with one of the slightest resumes in Presidential history. Malicious rumors were circulated that he had been born outside of the U.S. (sound familiar?) and was therefore ineligible for the Presidency. One by one, cabinet members—looking askance at this accidental President, and mindful of their careers—resigned and had to be replaced. Only the Secretary of War, Robert Lincoln (son of Abraham), stayed on for all of Arthur's term. A great many people expected Arthur to act like a creature of the spoils system, a typically corrupt big-city politician—but that is not how he acted. He embraced the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act, which stipulated that government jobs be offered on the basis of competence and not political patronage, that competence be rated by competitive exams, and that a United States Civil Service Commission be created to oversee the process. Arthur signed it into law in January, 1883, and it proved the central attainment of his Presidency. It raised the ire of his old friend Conkling, who had of course wanted machine politics to continue as ever (Conkling called it the "Snivel Service Act"). And old New York cronies came away disappointed when they approached Arthur for favors.

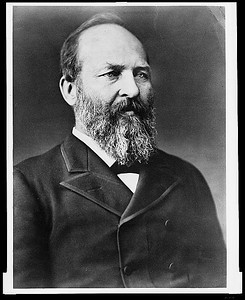

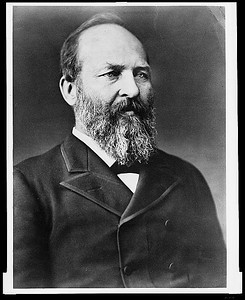

James A. Garfield, 20th President of the

United States and its second to die by

an assassin. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

Arthur also did much to revive the moribund U.S. Navy by pushing to fund the construction of steel-plated vessels. On other fronts, results for his administration were more mixed and frustrating. Arthur had the courage to veto the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which included a 20-year ban on immigration from China and denied citizenship to Chinese immigrants. But when the ban was cut to ten years, he grudgingly signed the bill, knowing that another veto would be overridden and weaken his Presidency. In the area of Civil Rights, he sought to combat the reemergence of the Southern Democrats and their disenfranchisement of black voters. To this end, he forged alliances with the new (and notably liberal) Readjuster and Greenback Parties. These efforts failed except for the brief tenure of the Readjusters in Virginia, where white supremacy's tide ultimately drowned that party's bi-racial coalition. Arthur also pushed with some success to fund education for American Indians. He pressed as well for the "allotment system," whereby individual tribe members and not tribes could own land. This system was not adopted until the first Grover Cleveland administration and then proved harmful to those it was supposed to help, with much Native land resold cheap to speculators.

A charming sophisticate, Arthur dressed stylishly, enjoyed the social whirl and had the Executive Mansion refurbished. "Elegant Arthur" was one of his nicknames, according to author Anthony Bergen (whose Arthur post on his terrific Dead Presidents website informs some finer points of this one—and here is his link: href=http://deadpresidents.tumblr.com). His reintroduction of liquor to Presidential get-togethers brought a harrumph from former President Hayes, who had banned it. For Henry Adams, the historian and member of the Adams political family, Arthur's stylishness and social aptitude denoted something rotten; with a puritanical sniff, he dismissed the administration as "the centre for every element of corruption." But by the end of Arthur's time in office, this was a minority opinion. Mark Twain said, "It would be hard indeed to better President Arthur's administration," while journalist Alexander McClure declared, "No man ever entered the Presidency more profoundly and widely distrusted than Chester Alan Arthur, and no one ever retired . . . more generally respected, alike by political friend and foe." In his Oxford History Of The American People, historian Samuel Eliot Morison wrote, "Arthur's administration stands up as the best Republican one between Lincoln and Theodore Roosevelt."

Late in 1882, however, Arthur's life darkened when he was diagnosed with Bright's disease (now called nephritis), a chronic kidney ailment that ensured he would not live to old age. Questions about his health were successfully deflected. Still, the illness certainly figured into his decision not to seek the Republican nomination in 1884. After leaving office, he lived only another year and nine months and in increasing misery, dying on November 18, 1886. On his deathbed he asked Chester Jr. to destroy all of his private and public documents and his son complied, burning the papers in trash cans. As a result, studies of the Arthur administration can only go so wide and deep. Why did he have his papers burned? A good guess is that his former image as a corrupt machine politician still pained him—and that in this last act, he hoped to shield himself against the harshly interpretive eye of history. I don't think he need have worried.

Anyway—even though it has little to do with the Civil War and even less with my novel Lucifer's Drum, here is my submission to that NPR 3-Minute Fiction contest:

ARTHUR’S PHANTOMS: OCTOBER, 1882

The Surgeon General’s diagnosis had drawn a stark border in time, dividing the last few hours from all the years before. And it seemed to have cleaved the President himself in two. At the desk, his ample body sat through a series of appointments while his soul observed from a ghost realm. His corporeal callers—the Secretary of State, just now, intoning about the Mexican trade agreement—remained oblivious as he watched the ghosts circulate.

One of them was Garfield, fierce-browed yet natty with his trimmed beard and black broadcloth suit, his watch fob glinting. Had he looked like this just before the madman shot him on the railroad platform? And had he lived, would he and his erstwhile running mate have grown to like each other? The President had admired Garfield as honest and intelligent—but Garfield had seemed to only half-reciprocate. No one had ever thought Chester Alan Arthur unintelligent, though many thought him untrustworthy—a foul creature of the Conkling machine, an overfed New York dandy spattered with political sewage. Without Arthur to knit up the Stalwart faction, Garfield would not have been elected—and yet as Vice-President, Arthur had been made to feel leprous.

As Garfield exited, Little William in his white baby clothes came stumbling, passing so close that the President nearly reached for him. The Secretary of State paused in his exposition, one eyebrow arching. “Please go on,” Arthur prodded. William smiled through pink gums and was gone, leaving an oddly precise ache in the President’s fingertips.

With the inevitability of autumn rain, Nell came next. Nell with whorled raven hair, face molded like a chalice. Nell in ivory taffeta, as young as her portrait in the East Room, where daily flowers kept vigil. As her lustrous eyes turned his way, he recalled them dimming with resentment for his late nights, his long absences in the party’s service. A Virginia lass, highborn. During the war, some had suspected Nell’s loyalty to the North. Whatever the truth, they had never known her. And they did not know him.

“I am a Stalwart,” Garfield’s assassin had declared, “—and Arthur will be President!” Some had speculated about a wider plot. And when the man’s lunacy had become too evident, they resorted to questioning Arthur’s citizenship. Born in Ireland, they said—and when that story didn’t work, born in Canada. More had simply shaken their heads, incredulous that a mere vassal of the spoils system, onetime Collector of the Port of New York, was now President of the United States.

The grotesqueries of “public discourse”—calls to exterminate the Indians, to shut out the Chinese, to keep the Negroes whipped and impoverished—were a giant trope for all the private, individual crimes committed round-the-clock. The easy judgment, the cold dismissal, the proud pontification. Self-styled reformers could be as vain as the most corrupt potentate, as vicious as any masked nightrider. But Arthur would give them reform. Oh, they would choke on reform. The Civil Service Bill was just the beginning—and when he was finished, their hunger for judgment would have to go sniffing elsewhere.

When the Secretary departed, Nell glided out after him. The spectral visitations, Arthur realized, had ceased for now. Standing at the French doors, he watched the wind-blown shrubbery outside, the low pewter clouds moving fast. His hand moved to the burning spot below his ribcage. Bright’s Disease—it was both daunting and reassuring to have it named. Specialists would have to be quietly summoned, a story concocted for the people. Not yet could he join the realm of phantoms.

This past Presidents Day (Feb. 16) brought to mind an NPR-sponsored contest I entered in the fall of 2012, "3-Minute Fiction: Pick A President." Contestants were told to submit a 600-word entry—about 3 minutes' reading time—focusing on any U.S. President, even a fictitious one. Over the weeks they read some of the entries on-air or posted them on the NPR site and I enjoyed all of them. The winner in the end was very good and quite original, featuring a man whose dementia-plagued father believed that Spiro Agnew had succeeded Nixon as President.

My submission was probably doomed to obscurity when I decided that it should be about our 21st President, Chester Alan Arthur. Why did I do this? Why did I pick my man from the gray middle of the pack—a virtual guarantee that it would be like throwing a jellybean into the Grand Canyon and waiting for an echo? The answer is straight from History Nerd Central: I am a champion of Chester A. I think he was a decent guy who made the best of a daunting situation. And I think he belongs farther up the rankings than historians often place him.

Chester A. Arthur, 21st President

of the United States.

(Courtesy: Library of Congress)

In the giant shadow of Abraham Lincoln, in a landscape gibbering with the ghosts of over 700,000 dead—and with the failure of Reconstruction, the maw of Jim Crow opening wide—post-Civil War politics seemed overpopulated with men who were bitter, vengeful, venal, corrupt and small. As far as Presidents go, many of us tend to think of the 36 years between Lincoln and the bright comet of Teddy Roosevelt as a kind of trough. Given this, it is surprising to actually look at who got into the Executive Mansion. Apart from Andrew Johnson and Benjamin Harrison—consistently rated as bottom-feeders—the United States was lucky to have these men available for the office. A few like Arthur were natural administrators; others like Ulysses S. Grant were not, but at least showed themselves to be fundamentally good and honest. It could definitely have been worse, as Johnson and Harrison abundantly proved.

Arthur was born in Fairfield, Vermont in 1829. His Irish-born father was a teacher-turned-minister and bedrock Abolitionist. Arthur (whose family always called him "Alan") started out as a teacher but ultimately switched to the law and New York City. Upon his admission to the bar, he joined the firm of the Abolitionist lawyer and family friend Erastus T. Culver, who then made him a partner. He lost no time distinguishing himself, helping to win the Lemmon v. New York decision, which established that any slave transported to New York State was automatically free.

Soon afterward, in 1854, Arthur served as lead attorney for Elizabeth Jennings Graham, a black schoolteacher and church organist. Late for service one Sunday, Graham had boarded a New York City streetcar which turned out to be whites-only. The conductor ordered her off but she insisted on her right to ride. Only after putting up an impressive physical fight with the conductor and a policeman before a hostile crowd was she forced off the car. It should perhaps have been clear right then that they had messed with the wrong church lady—but it definitely became so when Arthur took up her case. (Something else that might have made them think twice: Graham was the daughter of wealthy clothing store owner Thomas L. Jennings, founder of the Abyssinian Baptist Church and also the Legal Rights Association, which targeted racist statutes.) The next year—a full century before Rosa Parks—Arthur won Graham's suit against the conductor, the driver and the Third Avenue Railroad Company, which then had to desegregate its streetcars. Thanks in large part to the decision, all of NYC's public transit services were desegregated by the end of the Civil War. Elizabeth Graham went on to found the city's first kindergarten for black children.

Elizabeth Jennings Graham (1827-1901), civil

rights heroine and successful Arthur client.

(Courtesy: Kansas Historical Foundation)

By the time of the Civil War, Arthur had his own law practice, was deeply involved in Republican politics and married to the Virginia belle Ellen "Nell" Herndon, daughter of naval officer and explorer William Lewis Herndon (who was lost in the sinking of the SS Central America in 1857.) In 1861 the governor of New York assigned Arthur to the state's quartermaster department with the rank of brigadier general. He was so effective at housing and equipping the new troops that deluged NYC that he was soon promoted to inspector general and then quartermaster. He would have gone to the front as a regimental colonel if not for the governor's personal plea for him to maintain his home-front role. Yet that role was a political appointment and when the Democrats took over state government in 1863, Arthur lost his post.

Soon after this, he and Nell suffered the death of their three-year-old son William from illness. Nell gave birth to another son, Chester Alan Jr., the following year. In their ongoing grief over William, they heaped indulgence on young Chester, who grew up to be a rich, idle, attention-loving playboy. In 1871 they had a daughter, Ellen, who would lead a much lower-profile life. That same year saw Arthur named Collector of the Port of New York—a federal appointment and a highly lucrative one, typifying the spoils system and its routine rewards for political loyalty. It was a corrupt system, though then fully legal and Arthur personally quite honest. By the mid-1870's, however, the fever for civil service reform threatened to split the Republicans between the reform-minded "Half-Breeds" and the more traditional and complacent "Stalwarts," with the political machine of Senator Roscoe Conkling (Arthur's friend and patron) embodying the latter. The conflict resulted in President Rutherford B. Hayes sacking Arthur in 1878, an experience that left Arthur feeling branded as corrupt.

Arthur's ever-increasing work for the Conkling machine led to late nights and long absences, which strained his marriage. He was away in Albany in January 1880 when Nell died of pneumonia at age 42, causing him a sense of guilt that never quite abated. Within a year of this, he was catapulted to the Vice Presidency of the United States. The tumultuous 1880 Republican convention ended up nominating the "dark horse" (compromise, unforeseen) candidate James A. Garfield of Ohio for President. A champion of the Half-Breed faction, Garfield sought to mend the party split by choosing the Stalwart Arthur as his running mate. Arthur readily accepted the offer despite Conkling's urging that he not. His role in the election proved crucial, as the Republicans won by a wafer-thin 9,070 in the popular vote.

Ellen "Nell" Herndon Arthur (1837-1880), wife of Chester

A. Arthur. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

Arthur and Garfield immediately became estranged, however, over the latter's resistance to appointing Stalwarts to important posts. Arthur was in Albany on July 2, 1881, when he heard that Garfield had been shot and grievously wounded on a Washington railroad platform. Most unfortunately for Arthur, the assassin Charles J. Guiteau had declared on the spot, "I am a Stalwart, and Arthur will be President!" Never mind that Guiteau (often described as "a disappointed office-seeker") would make Booth and Oswald look like poster boys for mental health—the statement stoked public mistrust of Arthur, due to his background in urban machine politics.

Over the terrible eleven weeks that it took President Garfield to die, Constitutional constraints and Arthur's reluctance to seem presumptuous re: presidential authority (he stayed the whole time in NYC) created a power vacuum, ending only with Garfield's death on Sept. 19. And here I must say—the full tragedy of James Garfield's murder is lost on us today. He was smart, honest, gutsy, highly competent and a talented orator. Though President for only six and half months, the final two and a half spent bedridden and in pain, he had shown himself to be a quality leader, one who belonged in high office. As a for-instance, his feeling for the plight of African Americans was genuine, his intentions for them heartfelt without being especially naive; he in fact appointed a number of them to prominent posts, at a time when it was increasingly risky to do so. The tragedy would have been compounded had an Andrew Johnson been waiting in the wings to assume power. Luckily for all of us, though, it was Chester A. Arthur.

Widespread skepticism greeted Arthur's swearing-in. He came to the office with one of the slightest resumes in Presidential history. Malicious rumors were circulated that he had been born outside of the U.S. (sound familiar?) and was therefore ineligible for the Presidency. One by one, cabinet members—looking askance at this accidental President, and mindful of their careers—resigned and had to be replaced. Only the Secretary of War, Robert Lincoln (son of Abraham), stayed on for all of Arthur's term. A great many people expected Arthur to act like a creature of the spoils system, a typically corrupt big-city politician—but that is not how he acted. He embraced the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act, which stipulated that government jobs be offered on the basis of competence and not political patronage, that competence be rated by competitive exams, and that a United States Civil Service Commission be created to oversee the process. Arthur signed it into law in January, 1883, and it proved the central attainment of his Presidency. It raised the ire of his old friend Conkling, who had of course wanted machine politics to continue as ever (Conkling called it the "Snivel Service Act"). And old New York cronies came away disappointed when they approached Arthur for favors.

James A. Garfield, 20th President of the

United States and its second to die by

an assassin. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

Arthur also did much to revive the moribund U.S. Navy by pushing to fund the construction of steel-plated vessels. On other fronts, results for his administration were more mixed and frustrating. Arthur had the courage to veto the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which included a 20-year ban on immigration from China and denied citizenship to Chinese immigrants. But when the ban was cut to ten years, he grudgingly signed the bill, knowing that another veto would be overridden and weaken his Presidency. In the area of Civil Rights, he sought to combat the reemergence of the Southern Democrats and their disenfranchisement of black voters. To this end, he forged alliances with the new (and notably liberal) Readjuster and Greenback Parties. These efforts failed except for the brief tenure of the Readjusters in Virginia, where white supremacy's tide ultimately drowned that party's bi-racial coalition. Arthur also pushed with some success to fund education for American Indians. He pressed as well for the "allotment system," whereby individual tribe members and not tribes could own land. This system was not adopted until the first Grover Cleveland administration and then proved harmful to those it was supposed to help, with much Native land resold cheap to speculators.

A charming sophisticate, Arthur dressed stylishly, enjoyed the social whirl and had the Executive Mansion refurbished. "Elegant Arthur" was one of his nicknames, according to author Anthony Bergen (whose Arthur post on his terrific Dead Presidents website informs some finer points of this one—and here is his link: href=http://deadpresidents.tumblr.com). His reintroduction of liquor to Presidential get-togethers brought a harrumph from former President Hayes, who had banned it. For Henry Adams, the historian and member of the Adams political family, Arthur's stylishness and social aptitude denoted something rotten; with a puritanical sniff, he dismissed the administration as "the centre for every element of corruption." But by the end of Arthur's time in office, this was a minority opinion. Mark Twain said, "It would be hard indeed to better President Arthur's administration," while journalist Alexander McClure declared, "No man ever entered the Presidency more profoundly and widely distrusted than Chester Alan Arthur, and no one ever retired . . . more generally respected, alike by political friend and foe." In his Oxford History Of The American People, historian Samuel Eliot Morison wrote, "Arthur's administration stands up as the best Republican one between Lincoln and Theodore Roosevelt."

Late in 1882, however, Arthur's life darkened when he was diagnosed with Bright's disease (now called nephritis), a chronic kidney ailment that ensured he would not live to old age. Questions about his health were successfully deflected. Still, the illness certainly figured into his decision not to seek the Republican nomination in 1884. After leaving office, he lived only another year and nine months and in increasing misery, dying on November 18, 1886. On his deathbed he asked Chester Jr. to destroy all of his private and public documents and his son complied, burning the papers in trash cans. As a result, studies of the Arthur administration can only go so wide and deep. Why did he have his papers burned? A good guess is that his former image as a corrupt machine politician still pained him—and that in this last act, he hoped to shield himself against the harshly interpretive eye of history. I don't think he need have worried.

Anyway—even though it has little to do with the Civil War and even less with my novel Lucifer's Drum, here is my submission to that NPR 3-Minute Fiction contest:

ARTHUR’S PHANTOMS: OCTOBER, 1882

The Surgeon General’s diagnosis had drawn a stark border in time, dividing the last few hours from all the years before. And it seemed to have cleaved the President himself in two. At the desk, his ample body sat through a series of appointments while his soul observed from a ghost realm. His corporeal callers—the Secretary of State, just now, intoning about the Mexican trade agreement—remained oblivious as he watched the ghosts circulate.

One of them was Garfield, fierce-browed yet natty with his trimmed beard and black broadcloth suit, his watch fob glinting. Had he looked like this just before the madman shot him on the railroad platform? And had he lived, would he and his erstwhile running mate have grown to like each other? The President had admired Garfield as honest and intelligent—but Garfield had seemed to only half-reciprocate. No one had ever thought Chester Alan Arthur unintelligent, though many thought him untrustworthy—a foul creature of the Conkling machine, an overfed New York dandy spattered with political sewage. Without Arthur to knit up the Stalwart faction, Garfield would not have been elected—and yet as Vice-President, Arthur had been made to feel leprous.

As Garfield exited, Little William in his white baby clothes came stumbling, passing so close that the President nearly reached for him. The Secretary of State paused in his exposition, one eyebrow arching. “Please go on,” Arthur prodded. William smiled through pink gums and was gone, leaving an oddly precise ache in the President’s fingertips.

With the inevitability of autumn rain, Nell came next. Nell with whorled raven hair, face molded like a chalice. Nell in ivory taffeta, as young as her portrait in the East Room, where daily flowers kept vigil. As her lustrous eyes turned his way, he recalled them dimming with resentment for his late nights, his long absences in the party’s service. A Virginia lass, highborn. During the war, some had suspected Nell’s loyalty to the North. Whatever the truth, they had never known her. And they did not know him.

“I am a Stalwart,” Garfield’s assassin had declared, “—and Arthur will be President!” Some had speculated about a wider plot. And when the man’s lunacy had become too evident, they resorted to questioning Arthur’s citizenship. Born in Ireland, they said—and when that story didn’t work, born in Canada. More had simply shaken their heads, incredulous that a mere vassal of the spoils system, onetime Collector of the Port of New York, was now President of the United States.

The grotesqueries of “public discourse”—calls to exterminate the Indians, to shut out the Chinese, to keep the Negroes whipped and impoverished—were a giant trope for all the private, individual crimes committed round-the-clock. The easy judgment, the cold dismissal, the proud pontification. Self-styled reformers could be as vain as the most corrupt potentate, as vicious as any masked nightrider. But Arthur would give them reform. Oh, they would choke on reform. The Civil Service Bill was just the beginning—and when he was finished, their hunger for judgment would have to go sniffing elsewhere.

When the Secretary departed, Nell glided out after him. The spectral visitations, Arthur realized, had ceased for now. Standing at the French doors, he watched the wind-blown shrubbery outside, the low pewter clouds moving fast. His hand moved to the burning spot below his ribcage. Bright’s Disease—it was both daunting and reassuring to have it named. Specialists would have to be quietly summoned, a story concocted for the people. Not yet could he join the realm of phantoms.

Published on March 03, 2015 18:58

•

Tags:

chester-a-arthur, lucifer-s-drum, npr-pick-a-president

February 7, 2015

The Copperheads

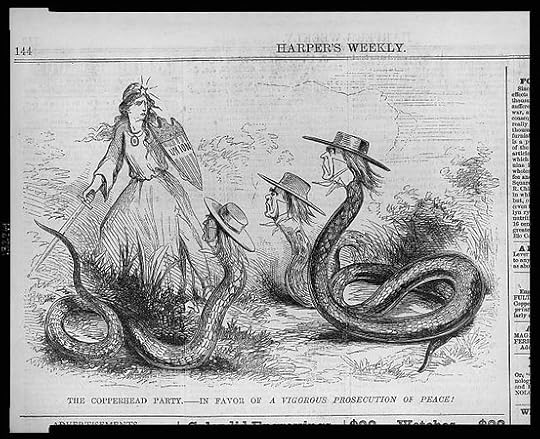

In the opening chapter of my novel Lucifer's Drum (which I hope to post here presently), the hack newspaper publisher Gideon Van Gilder meets an especially unpleasant end. Van Gilder is a Copperhead, or "Peace Democrat"—one of that loud Northern political faction opposed to Lincoln, the Draft and Emancipation. Most Copperheads favored preservation of the Union but proclaimed the right of the Southern and border states to maintain slavery. And they opposed black advancement on principle, whether free or slave, portraying the white majority as besieged by evil forces. They identified as Democrats and strongly influenced the direction of that party, whose 1864 presidential platform was wholly Copperhead. Still, it has to be stated that many thousands of non-Copperhead Democrats ("War Democrats") fought in the federal ranks.

The name came about as an epithet, when Republicans and Union loyalists in general compared these dissenters to venomous snakes. As with many such movements, supporters reacted by taking the name as a badge of honor—quite literally, in this case, cutting the Liberty symbol from copper pennies and proudly wearing them. They were strongest in areas just north of the Ohio River and in urban ethnic neighborhoods. Anyone who thinks that today's level of political vituperation is unmatched should check out the editorial commentary (and the cartoons) from Copperhead newspapers, especially during the '64 election season. The editor of Wisconsin's LaCrosse Democrat, Marcus "Brick" Pomeroy, branded Lincoln "fungus from the corrupt womb of bigotry and fanaticism . . . a worse tyrant and more inhuman butcher than has existed since the days of Nero." Pomeroy declared that anyone who voted for the President was "a traitor and murderer," and that "if he is elected to misgovern for another four years, we trust some bold hand will pierce his heart with dagger point for the public good." (As is often the case in times of civil tumult, men like Pomeroy defined treason and fanaticism as anything short of their own views—practically a textbook definition of true fanaticism.)

Anti-Copperhead cartoon, February 1863. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

In New York, the official Catholic paper The Metropolitan Record championed draft resistance and helped ignite the July 1863 riots, still the bloodiest such event in U.S. history. Largely Irish immigrant mobs lynched a number of black men in the street and burned black-owned businesses. They also burned and looted the Colored Orphan's Asylum, whose terrified residents (233 children plus staff) had to be shepherded to safety by police. Many of the troops called in to quell the riots had fought at Gettysburg just two weeks earlier, arriving exhausted and no doubt disoriented by the scorched urban setting. (Gideon Van Gilder is depicted as having played a similar role in inciting this mass violence.) The editor of The Record, John Mullaly, was arrested a year later for his anti-draft activities. For the most part, however, Union authorities had to put up with high-profile Copperheads like New York's mayor and later congressman Fernando Wood, who once proposed that the city secede and thereby maintain its lucrative cotton trade with the South. (Generally speaking, it has always seemed to me that where money goes, heartfelt conviction follows.)

The core of the Copperhead movement grew from The Knights Of The Golden Circle, a pro-slavery and pro-expansionist secret society formed in the 1850's. During the war it changed its name to The Order Of American Knights and then The Order Of The Sons of Liberty, headed by the Copperheads' most prominent spokesman Clement L. Vallandigham. Given the thrill of secrecy and the sense of their own historic role, the Knights and their successors tended toward the grandiose, calling their branches "castles" and sometimes using secret handshakes. (The Ku Klux Klan would later take this sort of stuff to unexplored heights.)

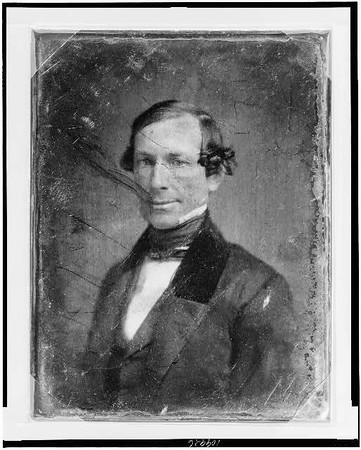

Fernando Wood, Mayor of New York City (1855-58,

1860-62), pro-Confederate and post-war U.S. Congressman.

(Courtesy: Library of Congress)

The Copperheads' fortunes ebbed and flowed along with that of the Union military cause, but reached their high-water mark in '64. What effectiveness they had evaporated on Sept. 2, when the fall of Atlanta made eventual Union victory look certain. Shortly before this, the Democrats had nominated George B. McClellan for president; however much McClellan despised Lincoln, who had sacked him as commanding general in the East, he did not embrace the Copperheads—contradicting the platform on which he supposedly ran and leaving his candidacy hamstrung. Among the Copperheads, only a minority were radical and nervy enough to actually participate in anti-Union schemes, such as encouraging soldiers to desert. And it is probably true that the Republicans exaggerated the Copperhead threat for political gain. Yet movement leaders like Harrison H. Dodd did in fact advocate the violent overthrow of certain state governments. Dodd and others were implicated in a plot to help Confederate prisoners escape from a POW camp in Indiana—and when federal authorities foiled it and made arrests, the evidence was compelling. Several Copperheads were sentenced to hang, but the Supreme Court eventually freed them after deciding that they should have had a civil and not a military trial.

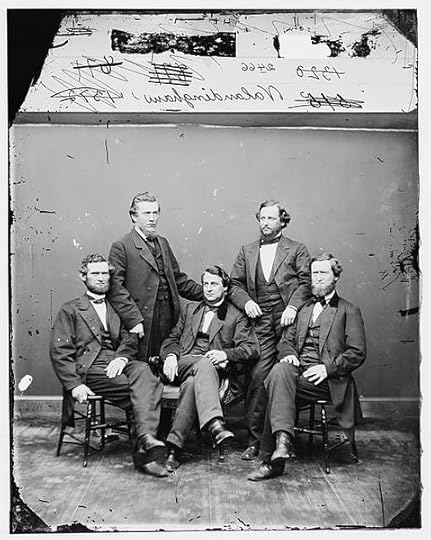

I can't end this without a quick focus on Clement Vallandigham. He was a two-term Ohio congressman who blamed the war on the Abolition movement and railed against Lincoln's suspension of habeas corpus. By the time he was voted out of office, he was the acknowledged leader of the Copperheads. Back in Ohio, he confronted General Ambrose E. Burnside's ham-fisted General Order No. 38, which mandated arrest for anyone expressing Confederate sympathies. (Burnside had acted on this when he shut down the pro-Copperhead Chicago Times, only to have Lincoln reverse the ban as soon as he heard of it.) Vallandigham was arrested under this order in May 1863 and sentenced to prison for the duration of the war. Facing loud protests from Democrats, however, Lincoln altered the sentence to banishment behind Confederate lines.

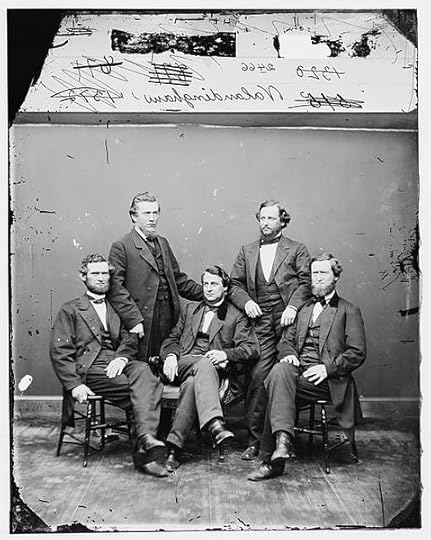

Clement Vallandigham (seated center) with other prominent

Copperheads, circa 1865. Several years later, he would accidentally

shoot himself. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

In time, Vallandigham left the South by blockade runner and ended up in Windsor, Ontario, from which he ran in absentia for the Ohio governorship. His campaign was strong but unsuccessful. Meanwhile, in the same trial that convicted Harrison Dodd and other Copperheads, testimony implicated Vallandigham in a plan for armed revolt—the so-called Northwest Conspiracy. He had allegedly sought funds from a Confederate agent for this purpose, but the charge was never pressed. By now he had slipped back into the United States and was being monitored by Union authorities; Lincoln with his usual shrewdness declined to have Vallandigham arrested again and made a martyr. Vallandigham even attended the Democatic convention as a delegate in Chicago. Despite strong disagreements with McClellan, he would have been named Secretary of War had Little Mac not been crushed at the polls that autumn.

After the war, Vallandigham ran losing campaigns for senator and congressman before resuming his law practice. He opposed black suffrage and anything hinting at racial equality but then endorsed the Democrats' "New Departure" policy, which basically discouraged all public mention of the war. In Lebanon, Ohio in June, 1871, he took up the case of Thomas McGehan, who was charged with shooting another man in a barroom brawl. At the Golden Lamb Inn, Vallandigham sought to demonstrate for fellow defense lawyers how the victim might have accidentally shot himself during the melee. Picking up a pistol he thought to be unloaded—but was not—Vallandigham pocketed the weapon but snagged it on his clothes, shooting himself in the stomach. He died the next day, aged 50, expressing faith in the Presbyterian concept of predestination. Needless to say, Thomas McGehan got off—only to be shot dead in another brawl four years later. Say what you want about Vallandigham's political beliefs—has any attorney ever gone quite so above and beyond for his client? And at least his death wasn't as bad as Van Gilder's.

The name came about as an epithet, when Republicans and Union loyalists in general compared these dissenters to venomous snakes. As with many such movements, supporters reacted by taking the name as a badge of honor—quite literally, in this case, cutting the Liberty symbol from copper pennies and proudly wearing them. They were strongest in areas just north of the Ohio River and in urban ethnic neighborhoods. Anyone who thinks that today's level of political vituperation is unmatched should check out the editorial commentary (and the cartoons) from Copperhead newspapers, especially during the '64 election season. The editor of Wisconsin's LaCrosse Democrat, Marcus "Brick" Pomeroy, branded Lincoln "fungus from the corrupt womb of bigotry and fanaticism . . . a worse tyrant and more inhuman butcher than has existed since the days of Nero." Pomeroy declared that anyone who voted for the President was "a traitor and murderer," and that "if he is elected to misgovern for another four years, we trust some bold hand will pierce his heart with dagger point for the public good." (As is often the case in times of civil tumult, men like Pomeroy defined treason and fanaticism as anything short of their own views—practically a textbook definition of true fanaticism.)

Anti-Copperhead cartoon, February 1863. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

In New York, the official Catholic paper The Metropolitan Record championed draft resistance and helped ignite the July 1863 riots, still the bloodiest such event in U.S. history. Largely Irish immigrant mobs lynched a number of black men in the street and burned black-owned businesses. They also burned and looted the Colored Orphan's Asylum, whose terrified residents (233 children plus staff) had to be shepherded to safety by police. Many of the troops called in to quell the riots had fought at Gettysburg just two weeks earlier, arriving exhausted and no doubt disoriented by the scorched urban setting. (Gideon Van Gilder is depicted as having played a similar role in inciting this mass violence.) The editor of The Record, John Mullaly, was arrested a year later for his anti-draft activities. For the most part, however, Union authorities had to put up with high-profile Copperheads like New York's mayor and later congressman Fernando Wood, who once proposed that the city secede and thereby maintain its lucrative cotton trade with the South. (Generally speaking, it has always seemed to me that where money goes, heartfelt conviction follows.)

The core of the Copperhead movement grew from The Knights Of The Golden Circle, a pro-slavery and pro-expansionist secret society formed in the 1850's. During the war it changed its name to The Order Of American Knights and then The Order Of The Sons of Liberty, headed by the Copperheads' most prominent spokesman Clement L. Vallandigham. Given the thrill of secrecy and the sense of their own historic role, the Knights and their successors tended toward the grandiose, calling their branches "castles" and sometimes using secret handshakes. (The Ku Klux Klan would later take this sort of stuff to unexplored heights.)

Fernando Wood, Mayor of New York City (1855-58,

1860-62), pro-Confederate and post-war U.S. Congressman.

(Courtesy: Library of Congress)

The Copperheads' fortunes ebbed and flowed along with that of the Union military cause, but reached their high-water mark in '64. What effectiveness they had evaporated on Sept. 2, when the fall of Atlanta made eventual Union victory look certain. Shortly before this, the Democrats had nominated George B. McClellan for president; however much McClellan despised Lincoln, who had sacked him as commanding general in the East, he did not embrace the Copperheads—contradicting the platform on which he supposedly ran and leaving his candidacy hamstrung. Among the Copperheads, only a minority were radical and nervy enough to actually participate in anti-Union schemes, such as encouraging soldiers to desert. And it is probably true that the Republicans exaggerated the Copperhead threat for political gain. Yet movement leaders like Harrison H. Dodd did in fact advocate the violent overthrow of certain state governments. Dodd and others were implicated in a plot to help Confederate prisoners escape from a POW camp in Indiana—and when federal authorities foiled it and made arrests, the evidence was compelling. Several Copperheads were sentenced to hang, but the Supreme Court eventually freed them after deciding that they should have had a civil and not a military trial.

I can't end this without a quick focus on Clement Vallandigham. He was a two-term Ohio congressman who blamed the war on the Abolition movement and railed against Lincoln's suspension of habeas corpus. By the time he was voted out of office, he was the acknowledged leader of the Copperheads. Back in Ohio, he confronted General Ambrose E. Burnside's ham-fisted General Order No. 38, which mandated arrest for anyone expressing Confederate sympathies. (Burnside had acted on this when he shut down the pro-Copperhead Chicago Times, only to have Lincoln reverse the ban as soon as he heard of it.) Vallandigham was arrested under this order in May 1863 and sentenced to prison for the duration of the war. Facing loud protests from Democrats, however, Lincoln altered the sentence to banishment behind Confederate lines.

Clement Vallandigham (seated center) with other prominent

Copperheads, circa 1865. Several years later, he would accidentally

shoot himself. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

In time, Vallandigham left the South by blockade runner and ended up in Windsor, Ontario, from which he ran in absentia for the Ohio governorship. His campaign was strong but unsuccessful. Meanwhile, in the same trial that convicted Harrison Dodd and other Copperheads, testimony implicated Vallandigham in a plan for armed revolt—the so-called Northwest Conspiracy. He had allegedly sought funds from a Confederate agent for this purpose, but the charge was never pressed. By now he had slipped back into the United States and was being monitored by Union authorities; Lincoln with his usual shrewdness declined to have Vallandigham arrested again and made a martyr. Vallandigham even attended the Democatic convention as a delegate in Chicago. Despite strong disagreements with McClellan, he would have been named Secretary of War had Little Mac not been crushed at the polls that autumn.

After the war, Vallandigham ran losing campaigns for senator and congressman before resuming his law practice. He opposed black suffrage and anything hinting at racial equality but then endorsed the Democrats' "New Departure" policy, which basically discouraged all public mention of the war. In Lebanon, Ohio in June, 1871, he took up the case of Thomas McGehan, who was charged with shooting another man in a barroom brawl. At the Golden Lamb Inn, Vallandigham sought to demonstrate for fellow defense lawyers how the victim might have accidentally shot himself during the melee. Picking up a pistol he thought to be unloaded—but was not—Vallandigham pocketed the weapon but snagged it on his clothes, shooting himself in the stomach. He died the next day, aged 50, expressing faith in the Presbyterian concept of predestination. Needless to say, Thomas McGehan got off—only to be shot dead in another brawl four years later. Say what you want about Vallandigham's political beliefs—has any attorney ever gone quite so above and beyond for his client? And at least his death wasn't as bad as Van Gilder's.

Published on February 07, 2015 13:06

•

Tags:

civil-war, copperheads, knights-of-the-golden-circle, lucifer-s-drum, peace-democrats, vallandigham

December 6, 2014

Pat Cleburne

In my last post I was talking about the Battle of Franklin and its depiction in Howard Bahr's dark gem of a novel, The Black Flower. I can't think about that battle without recalling its most distinguished casualty, Confederate General Patrick Ronayne Cleburne. Among the 6200 Southern casualties were six dead generals plus seven wounded and one captured. None, however, represented as big a loss to the South as Cleburne, who was called "The Stonewall Of The West." Tough, smart, resourceful and loved by his men, Cleburne had been born in County Cork, Ireland and emigrated to the United States at the age of 21, settling in Helena, Arkansas. There he worked as a pharmacist and later as a newspaper publisher. When the war threatened, his personal qualities and military experience (three years in the British army) made him a natural choice as captain of a militia company, which he led in January 1861 to capture the Union arsenal at Little Rock.

Three tumultuous years later, Cleburne figured in a quiet but very telling episode of the war. Recognizing the South's great manpower disadvantage and the urgent need to address it, Cleburne proposed to General Joseph Johnston and the rest of the Army of Tennessee's leadership that the South begin freeing slaves in return for their enlistment in the Confederate forces. A crucial passage of his address reveals both his knowledge of history and his blindness to what he was up against:

Born and raised in another country and not arriving in the South till early manhood, Cleburne had never grasped how fundamental slavery actually was to the war and to his adopted region, even though it was the threat to slavery's spread that had triggered secession in the first place. (In the research for my novel Lucifer's Drum, one thing was clear: slavery imbued the pre-war years like no other issue. Nothing else came close.) The other generals listened quietly and respectfully, but Johnston was reportedly shocked. And—no surprise—Cleburne's proposal was not discussed, let alone acted upon. The basic idea persisted, however, as Confederate desperation intensified. And in early 1865—truly the 11th hour, long past the point where it could have had any effect—the Confederate Congress authorized the first feeble steps for slave recruitment. Within a few weeks, the Union had triumphed.

At Franklin on November 30, 1864, Cleburne correctly judged General John B. Hood's assault plan as foolhardy but followed orders, exposing himself to maximum danger as the charge proceeded. His troops momentarily breached the Union line but were thrown back. Cleburne died while charging on foot after his horse was shot out from under him. His body was found plundered, without boots, watch or sword. He deserved far better. Then again, there were so many others of whom you could say that—on any side, in any war.

Portrait of General Cleburne. (Courtesy:

Library of Congress)

Three tumultuous years later, Cleburne figured in a quiet but very telling episode of the war. Recognizing the South's great manpower disadvantage and the urgent need to address it, Cleburne proposed to General Joseph Johnston and the rest of the Army of Tennessee's leadership that the South begin freeing slaves in return for their enlistment in the Confederate forces. A crucial passage of his address reveals both his knowledge of history and his blindness to what he was up against:

Satisfy the negro that if he faithfully adheres to our standard during the war he shall receive his freedom and that of his race ... and we change the race from a dreaded weakness to a position of strength.

Will the slaves fight? The helots of Sparta stood their masters good stead in battle. In the great sea fight of Lepanto where the Christians checked forever the spread of Mohammedanism over Europe, the galley slaves of portions of the fleet were promised freedom, and called on to fight at a critical moment of the battle. They fought well, and civilization owes much to those brave galley slaves ... the experience of this war has been so far that half-trained negroes have fought as bravely as many other half-trained Yankees.

It is said that slavery is all we are fighting for, and if we give it up we give up all. Even if this were true, which we deny, slavery is not all our enemies are fighting for. It is merely the pretense to establish sectional superiority and a more centralized form of government, and to deprive us of our rights and liberties.

Born and raised in another country and not arriving in the South till early manhood, Cleburne had never grasped how fundamental slavery actually was to the war and to his adopted region, even though it was the threat to slavery's spread that had triggered secession in the first place. (In the research for my novel Lucifer's Drum, one thing was clear: slavery imbued the pre-war years like no other issue. Nothing else came close.) The other generals listened quietly and respectfully, but Johnston was reportedly shocked. And—no surprise—Cleburne's proposal was not discussed, let alone acted upon. The basic idea persisted, however, as Confederate desperation intensified. And in early 1865—truly the 11th hour, long past the point where it could have had any effect—the Confederate Congress authorized the first feeble steps for slave recruitment. Within a few weeks, the Union had triumphed.

At Franklin on November 30, 1864, Cleburne correctly judged General John B. Hood's assault plan as foolhardy but followed orders, exposing himself to maximum danger as the charge proceeded. His troops momentarily breached the Union line but were thrown back. Cleburne died while charging on foot after his horse was shot out from under him. His body was found plundered, without boots, watch or sword. He deserved far better. Then again, there were so many others of whom you could say that—on any side, in any war.

Portrait of General Cleburne. (Courtesy:

Library of Congress)

Published on December 06, 2014 16:29

•

Tags:

battle-of-franklin, civil-war, lucifer-s-drum, patrick-cleburne

November 29, 2014

Grim Anniversaries

Hi Everybody—

One thing that spurred me to publish Lucifer's Drum this past summer was that fact that the event it's based on—Jubal Early's nearly successful attack on Washington DC—was marking its 150th anniversary. But over the past three and a half years, practically any given day has commemorated the 150th anniversary of something bloody. Case in point: today marks 150 years since the Sand Creek Massacre in Colorado, when Col. John Chivington and his soldiers attacked a peaceful encampment of Cheyenne and Arapaho. They killed approximately 130 of them, including many women and children. The Cheyenne chief Black Kettle survived somehow, only to die in a similar sneak attack four years later, at the Washita River in present-day Oklahoma. This time the attacker was George Armstrong Custer, who that day earned a new nickname among the Cheyenne: Creeping Panther. It was during the Civil War that western expansion and consequent conflict with the western tribes entered its final and worst phase, a phase that would end in the freezing cold of Wounded Knee Creek in 1890.

And tomorrow will mark the sesquicentennial of the Battle of Franklin, south of Nashville. Which gives me the opportunity to speak of Howard Bahr's darkly beautiful gem The Black Flower. Franklin is the centerpiece for that novel. Unlike another work of Civil War fiction which had a big impact on me—Michael Shaara's The Killer Angels, with its classic depiction of Gettysburg—The Black Flower unfolds through the eyes of rank-and-file soldiers and of civilians, not colonels and generals. Its chief character is a Confederate rifleman, Bushrod Carter, who is mulling the possibility of becoming a deserter (a common thought, then, I'm sure, given what these men had been through and the growing sense of hopelessness) while events tumble toward grand-scale tragedy.

I don't think I can adequately convey the effect of Mr. Bahr's quiet restraint. Out of it rises something like an epic fugue, an anthem of sorrow. I am not saying it is all tone—the story is plenty gripping. The sense of what it was like—the texture of time and place, the sights and smells—is so potent that it makes you feel you have been teleported to Nov. 30, 1864. And the depiction of the battle—again, no general's eye-view but a foot soldier's—thrusts you into clamor, terror and chaos in a way I have never seen done. The moment before the doomed Confederate assault—a moment stretched to dreamlike infinity in the soldiers' minds—leaves you feeling, "Yes, it must have been like that." At the end you feel the satisfaction that comes with experiencing a fully realized work of art—but you also mourn, for people long dead.

For anyone who's interested, here is the Amazon link for The Black Flower:

http://www.amazon.com/Black-Flower-No...

Well, folks, gotta move. Talk at you again soon.

—Bernie

One thing that spurred me to publish Lucifer's Drum this past summer was that fact that the event it's based on—Jubal Early's nearly successful attack on Washington DC—was marking its 150th anniversary. But over the past three and a half years, practically any given day has commemorated the 150th anniversary of something bloody. Case in point: today marks 150 years since the Sand Creek Massacre in Colorado, when Col. John Chivington and his soldiers attacked a peaceful encampment of Cheyenne and Arapaho. They killed approximately 130 of them, including many women and children. The Cheyenne chief Black Kettle survived somehow, only to die in a similar sneak attack four years later, at the Washita River in present-day Oklahoma. This time the attacker was George Armstrong Custer, who that day earned a new nickname among the Cheyenne: Creeping Panther. It was during the Civil War that western expansion and consequent conflict with the western tribes entered its final and worst phase, a phase that would end in the freezing cold of Wounded Knee Creek in 1890.

And tomorrow will mark the sesquicentennial of the Battle of Franklin, south of Nashville. Which gives me the opportunity to speak of Howard Bahr's darkly beautiful gem The Black Flower. Franklin is the centerpiece for that novel. Unlike another work of Civil War fiction which had a big impact on me—Michael Shaara's The Killer Angels, with its classic depiction of Gettysburg—The Black Flower unfolds through the eyes of rank-and-file soldiers and of civilians, not colonels and generals. Its chief character is a Confederate rifleman, Bushrod Carter, who is mulling the possibility of becoming a deserter (a common thought, then, I'm sure, given what these men had been through and the growing sense of hopelessness) while events tumble toward grand-scale tragedy.

I don't think I can adequately convey the effect of Mr. Bahr's quiet restraint. Out of it rises something like an epic fugue, an anthem of sorrow. I am not saying it is all tone—the story is plenty gripping. The sense of what it was like—the texture of time and place, the sights and smells—is so potent that it makes you feel you have been teleported to Nov. 30, 1864. And the depiction of the battle—again, no general's eye-view but a foot soldier's—thrusts you into clamor, terror and chaos in a way I have never seen done. The moment before the doomed Confederate assault—a moment stretched to dreamlike infinity in the soldiers' minds—leaves you feeling, "Yes, it must have been like that." At the end you feel the satisfaction that comes with experiencing a fully realized work of art—but you also mourn, for people long dead.

For anyone who's interested, here is the Amazon link for The Black Flower:

http://www.amazon.com/Black-Flower-No...

Well, folks, gotta move. Talk at you again soon.

—Bernie

Published on November 29, 2014 13:48

•

Tags:

battle-of-franklin, bernie-mackinnon, civil-war-anniversaries, howard-bahr, lucifer-s-drum, sand-creek