Bernie MacKinnon's Blog - Posts Tagged "knights-of-the-golden-circle"

The Copperheads

In the opening chapter of my novel Lucifer's Drum (which I hope to post here presently), the hack newspaper publisher Gideon Van Gilder meets an especially unpleasant end. Van Gilder is a Copperhead, or "Peace Democrat"—one of that loud Northern political faction opposed to Lincoln, the Draft and Emancipation. Most Copperheads favored preservation of the Union but proclaimed the right of the Southern and border states to maintain slavery. And they opposed black advancement on principle, whether free or slave, portraying the white majority as besieged by evil forces. They identified as Democrats and strongly influenced the direction of that party, whose 1864 presidential platform was wholly Copperhead. Still, it has to be stated that many thousands of non-Copperhead Democrats ("War Democrats") fought in the federal ranks.

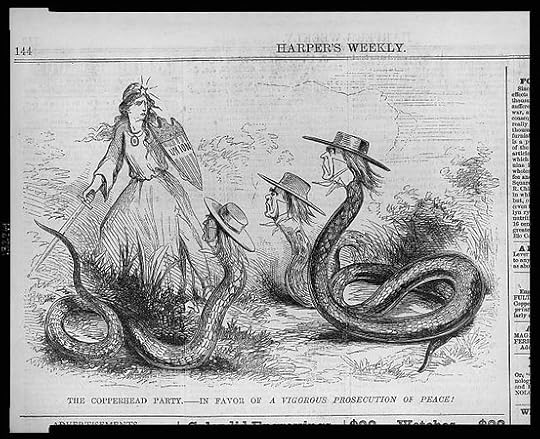

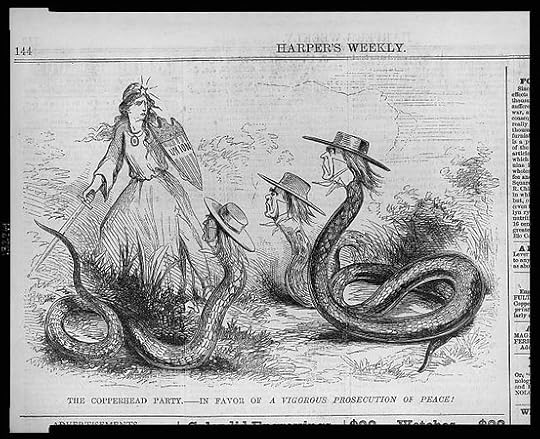

The name came about as an epithet, when Republicans and Union loyalists in general compared these dissenters to venomous snakes. As with many such movements, supporters reacted by taking the name as a badge of honor—quite literally, in this case, cutting the Liberty symbol from copper pennies and proudly wearing them. They were strongest in areas just north of the Ohio River and in urban ethnic neighborhoods. Anyone who thinks that today's level of political vituperation is unmatched should check out the editorial commentary (and the cartoons) from Copperhead newspapers, especially during the '64 election season. The editor of Wisconsin's LaCrosse Democrat, Marcus "Brick" Pomeroy, branded Lincoln "fungus from the corrupt womb of bigotry and fanaticism . . . a worse tyrant and more inhuman butcher than has existed since the days of Nero." Pomeroy declared that anyone who voted for the President was "a traitor and murderer," and that "if he is elected to misgovern for another four years, we trust some bold hand will pierce his heart with dagger point for the public good." (As is often the case in times of civil tumult, men like Pomeroy defined treason and fanaticism as anything short of their own views—practically a textbook definition of true fanaticism.)

Anti-Copperhead cartoon, February 1863. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

In New York, the official Catholic paper The Metropolitan Record championed draft resistance and helped ignite the July 1863 riots, still the bloodiest such event in U.S. history. Largely Irish immigrant mobs lynched a number of black men in the street and burned black-owned businesses. They also burned and looted the Colored Orphan's Asylum, whose terrified residents (233 children plus staff) had to be shepherded to safety by police. Many of the troops called in to quell the riots had fought at Gettysburg just two weeks earlier, arriving exhausted and no doubt disoriented by the scorched urban setting. (Gideon Van Gilder is depicted as having played a similar role in inciting this mass violence.) The editor of The Record, John Mullaly, was arrested a year later for his anti-draft activities. For the most part, however, Union authorities had to put up with high-profile Copperheads like New York's mayor and later congressman Fernando Wood, who once proposed that the city secede and thereby maintain its lucrative cotton trade with the South. (Generally speaking, it has always seemed to me that where money goes, heartfelt conviction follows.)

The core of the Copperhead movement grew from The Knights Of The Golden Circle, a pro-slavery and pro-expansionist secret society formed in the 1850's. During the war it changed its name to The Order Of American Knights and then The Order Of The Sons of Liberty, headed by the Copperheads' most prominent spokesman Clement L. Vallandigham. Given the thrill of secrecy and the sense of their own historic role, the Knights and their successors tended toward the grandiose, calling their branches "castles" and sometimes using secret handshakes. (The Ku Klux Klan would later take this sort of stuff to unexplored heights.)

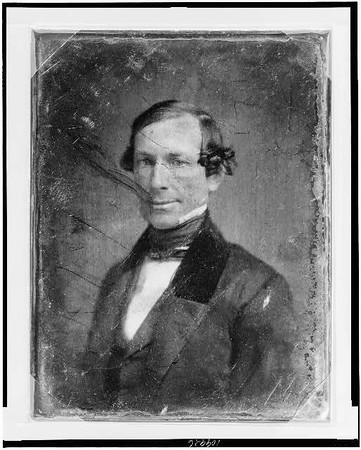

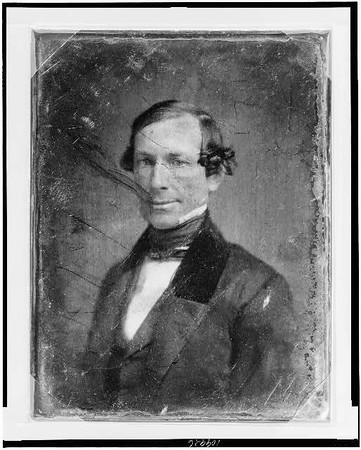

Fernando Wood, Mayor of New York City (1855-58,

1860-62), pro-Confederate and post-war U.S. Congressman.

(Courtesy: Library of Congress)

The Copperheads' fortunes ebbed and flowed along with that of the Union military cause, but reached their high-water mark in '64. What effectiveness they had evaporated on Sept. 2, when the fall of Atlanta made eventual Union victory look certain. Shortly before this, the Democrats had nominated George B. McClellan for president; however much McClellan despised Lincoln, who had sacked him as commanding general in the East, he did not embrace the Copperheads—contradicting the platform on which he supposedly ran and leaving his candidacy hamstrung. Among the Copperheads, only a minority were radical and nervy enough to actually participate in anti-Union schemes, such as encouraging soldiers to desert. And it is probably true that the Republicans exaggerated the Copperhead threat for political gain. Yet movement leaders like Harrison H. Dodd did in fact advocate the violent overthrow of certain state governments. Dodd and others were implicated in a plot to help Confederate prisoners escape from a POW camp in Indiana—and when federal authorities foiled it and made arrests, the evidence was compelling. Several Copperheads were sentenced to hang, but the Supreme Court eventually freed them after deciding that they should have had a civil and not a military trial.

I can't end this without a quick focus on Clement Vallandigham. He was a two-term Ohio congressman who blamed the war on the Abolition movement and railed against Lincoln's suspension of habeas corpus. By the time he was voted out of office, he was the acknowledged leader of the Copperheads. Back in Ohio, he confronted General Ambrose E. Burnside's ham-fisted General Order No. 38, which mandated arrest for anyone expressing Confederate sympathies. (Burnside had acted on this when he shut down the pro-Copperhead Chicago Times, only to have Lincoln reverse the ban as soon as he heard of it.) Vallandigham was arrested under this order in May 1863 and sentenced to prison for the duration of the war. Facing loud protests from Democrats, however, Lincoln altered the sentence to banishment behind Confederate lines.

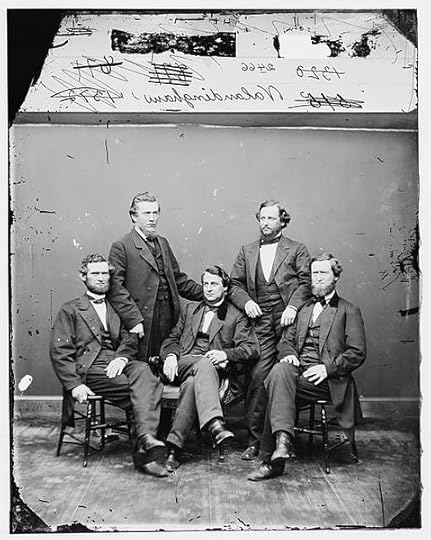

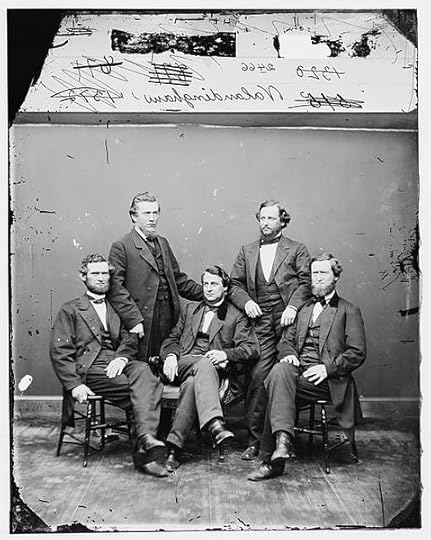

Clement Vallandigham (seated center) with other prominent

Copperheads, circa 1865. Several years later, he would accidentally

shoot himself. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

In time, Vallandigham left the South by blockade runner and ended up in Windsor, Ontario, from which he ran in absentia for the Ohio governorship. His campaign was strong but unsuccessful. Meanwhile, in the same trial that convicted Harrison Dodd and other Copperheads, testimony implicated Vallandigham in a plan for armed revolt—the so-called Northwest Conspiracy. He had allegedly sought funds from a Confederate agent for this purpose, but the charge was never pressed. By now he had slipped back into the United States and was being monitored by Union authorities; Lincoln with his usual shrewdness declined to have Vallandigham arrested again and made a martyr. Vallandigham even attended the Democatic convention as a delegate in Chicago. Despite strong disagreements with McClellan, he would have been named Secretary of War had Little Mac not been crushed at the polls that autumn.

After the war, Vallandigham ran losing campaigns for senator and congressman before resuming his law practice. He opposed black suffrage and anything hinting at racial equality but then endorsed the Democrats' "New Departure" policy, which basically discouraged all public mention of the war. In Lebanon, Ohio in June, 1871, he took up the case of Thomas McGehan, who was charged with shooting another man in a barroom brawl. At the Golden Lamb Inn, Vallandigham sought to demonstrate for fellow defense lawyers how the victim might have accidentally shot himself during the melee. Picking up a pistol he thought to be unloaded—but was not—Vallandigham pocketed the weapon but snagged it on his clothes, shooting himself in the stomach. He died the next day, aged 50, expressing faith in the Presbyterian concept of predestination. Needless to say, Thomas McGehan got off—only to be shot dead in another brawl four years later. Say what you want about Vallandigham's political beliefs—has any attorney ever gone quite so above and beyond for his client? And at least his death wasn't as bad as Van Gilder's.

The name came about as an epithet, when Republicans and Union loyalists in general compared these dissenters to venomous snakes. As with many such movements, supporters reacted by taking the name as a badge of honor—quite literally, in this case, cutting the Liberty symbol from copper pennies and proudly wearing them. They were strongest in areas just north of the Ohio River and in urban ethnic neighborhoods. Anyone who thinks that today's level of political vituperation is unmatched should check out the editorial commentary (and the cartoons) from Copperhead newspapers, especially during the '64 election season. The editor of Wisconsin's LaCrosse Democrat, Marcus "Brick" Pomeroy, branded Lincoln "fungus from the corrupt womb of bigotry and fanaticism . . . a worse tyrant and more inhuman butcher than has existed since the days of Nero." Pomeroy declared that anyone who voted for the President was "a traitor and murderer," and that "if he is elected to misgovern for another four years, we trust some bold hand will pierce his heart with dagger point for the public good." (As is often the case in times of civil tumult, men like Pomeroy defined treason and fanaticism as anything short of their own views—practically a textbook definition of true fanaticism.)

Anti-Copperhead cartoon, February 1863. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

In New York, the official Catholic paper The Metropolitan Record championed draft resistance and helped ignite the July 1863 riots, still the bloodiest such event in U.S. history. Largely Irish immigrant mobs lynched a number of black men in the street and burned black-owned businesses. They also burned and looted the Colored Orphan's Asylum, whose terrified residents (233 children plus staff) had to be shepherded to safety by police. Many of the troops called in to quell the riots had fought at Gettysburg just two weeks earlier, arriving exhausted and no doubt disoriented by the scorched urban setting. (Gideon Van Gilder is depicted as having played a similar role in inciting this mass violence.) The editor of The Record, John Mullaly, was arrested a year later for his anti-draft activities. For the most part, however, Union authorities had to put up with high-profile Copperheads like New York's mayor and later congressman Fernando Wood, who once proposed that the city secede and thereby maintain its lucrative cotton trade with the South. (Generally speaking, it has always seemed to me that where money goes, heartfelt conviction follows.)

The core of the Copperhead movement grew from The Knights Of The Golden Circle, a pro-slavery and pro-expansionist secret society formed in the 1850's. During the war it changed its name to The Order Of American Knights and then The Order Of The Sons of Liberty, headed by the Copperheads' most prominent spokesman Clement L. Vallandigham. Given the thrill of secrecy and the sense of their own historic role, the Knights and their successors tended toward the grandiose, calling their branches "castles" and sometimes using secret handshakes. (The Ku Klux Klan would later take this sort of stuff to unexplored heights.)

Fernando Wood, Mayor of New York City (1855-58,

1860-62), pro-Confederate and post-war U.S. Congressman.

(Courtesy: Library of Congress)

The Copperheads' fortunes ebbed and flowed along with that of the Union military cause, but reached their high-water mark in '64. What effectiveness they had evaporated on Sept. 2, when the fall of Atlanta made eventual Union victory look certain. Shortly before this, the Democrats had nominated George B. McClellan for president; however much McClellan despised Lincoln, who had sacked him as commanding general in the East, he did not embrace the Copperheads—contradicting the platform on which he supposedly ran and leaving his candidacy hamstrung. Among the Copperheads, only a minority were radical and nervy enough to actually participate in anti-Union schemes, such as encouraging soldiers to desert. And it is probably true that the Republicans exaggerated the Copperhead threat for political gain. Yet movement leaders like Harrison H. Dodd did in fact advocate the violent overthrow of certain state governments. Dodd and others were implicated in a plot to help Confederate prisoners escape from a POW camp in Indiana—and when federal authorities foiled it and made arrests, the evidence was compelling. Several Copperheads were sentenced to hang, but the Supreme Court eventually freed them after deciding that they should have had a civil and not a military trial.

I can't end this without a quick focus on Clement Vallandigham. He was a two-term Ohio congressman who blamed the war on the Abolition movement and railed against Lincoln's suspension of habeas corpus. By the time he was voted out of office, he was the acknowledged leader of the Copperheads. Back in Ohio, he confronted General Ambrose E. Burnside's ham-fisted General Order No. 38, which mandated arrest for anyone expressing Confederate sympathies. (Burnside had acted on this when he shut down the pro-Copperhead Chicago Times, only to have Lincoln reverse the ban as soon as he heard of it.) Vallandigham was arrested under this order in May 1863 and sentenced to prison for the duration of the war. Facing loud protests from Democrats, however, Lincoln altered the sentence to banishment behind Confederate lines.

Clement Vallandigham (seated center) with other prominent

Copperheads, circa 1865. Several years later, he would accidentally

shoot himself. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

In time, Vallandigham left the South by blockade runner and ended up in Windsor, Ontario, from which he ran in absentia for the Ohio governorship. His campaign was strong but unsuccessful. Meanwhile, in the same trial that convicted Harrison Dodd and other Copperheads, testimony implicated Vallandigham in a plan for armed revolt—the so-called Northwest Conspiracy. He had allegedly sought funds from a Confederate agent for this purpose, but the charge was never pressed. By now he had slipped back into the United States and was being monitored by Union authorities; Lincoln with his usual shrewdness declined to have Vallandigham arrested again and made a martyr. Vallandigham even attended the Democatic convention as a delegate in Chicago. Despite strong disagreements with McClellan, he would have been named Secretary of War had Little Mac not been crushed at the polls that autumn.

After the war, Vallandigham ran losing campaigns for senator and congressman before resuming his law practice. He opposed black suffrage and anything hinting at racial equality but then endorsed the Democrats' "New Departure" policy, which basically discouraged all public mention of the war. In Lebanon, Ohio in June, 1871, he took up the case of Thomas McGehan, who was charged with shooting another man in a barroom brawl. At the Golden Lamb Inn, Vallandigham sought to demonstrate for fellow defense lawyers how the victim might have accidentally shot himself during the melee. Picking up a pistol he thought to be unloaded—but was not—Vallandigham pocketed the weapon but snagged it on his clothes, shooting himself in the stomach. He died the next day, aged 50, expressing faith in the Presbyterian concept of predestination. Needless to say, Thomas McGehan got off—only to be shot dead in another brawl four years later. Say what you want about Vallandigham's political beliefs—has any attorney ever gone quite so above and beyond for his client? And at least his death wasn't as bad as Van Gilder's.

Published on February 07, 2015 13:06

•

Tags:

civil-war, copperheads, knights-of-the-golden-circle, lucifer-s-drum, peace-democrats, vallandigham