Rizwan Niaz Raiyan's Blog

October 16, 2025

High food prices in east and southern Africa: four steps to boost production and make markets work better

Countries in east and southern Africa have continued to experience high and volatile food prices despite good harvests in 2025. This is especially alarming as climate-related weather shocks will be deeper and more frequent.

Yet the region does not lack the potential to expand agriculture. Parts of the region have abundant arable land and water resources.

The G20 Food Security Task Force convened by South Africa as part of its G20 presidency has recognised the wide and persistent extent of hunger and malnutrition in most sub-regions of Africa. The task force highlighted excessive price volatility and food inflation despite sufficient global food production.

It affirmed:

the commitment to facilitate open, fair, predictable, and rules-based agriculture, food and fertiliser trade and reduce market distortions.

Evidence from the African Market Observatory, however, points to action – not words – being required. The prices for food products such as maize meal, rice and vegetable oil are very high across the region. So are those of inputs such as fertilizer.

The African Market Observatory provides market information, including prices, for key food products at the wholesale and producer levels in east and southern Africa. This data is essential in evaluating whether prices are fair and markets are working well for smaller producers and other market participants.

Countries in east and southern Africa have a combined population of over 600 million. As a whole the region is a substantial net importer of staples such as wheat, rice and vegetable oil. This despite the potential for the region to expand production.

But to expand production, countries would need to develop sustainable agro-industrial strategies. Such strategies include initiatives to improve yields, value-adding and the creation of fair regional markets. Improved water management and farming methods are essential along with investing in storage, logistics and processing.

Countries would also need to address the issue of agricultural commodity markets in the region. The variance in commodity prices across the region are evidence that markets are working very badly.

Prices vary across countriesMaize prices vary tremendously across the region, with extremely high prices in Kenya and Malawi. This should not be the case. When production from other parts of the region is taken into account, the region has more than enough maize to meet demand. There have been good rains this year after El Nino affected countries like Malawi and Zambia in 2024.

Prices in Kenya have been above US$450/tonne while prices in Zambia from April to June 2025 after the harvest were around US$200/tonne. Tanzania and Uganda have also had good harvests with prices under US$300/tonne in producing areas. Transport costs can account for around US$80/tonne of the difference, at most (less from Uganda and Tanzania).

Zambia maintained export restrictions until August, which meant farmers received low prices and the traders who bought up the harvest made windfall profits when the restrictions were lifted.

There have been similar differences in soybeans between what farmers receive and prices paid by customers. Soymeal from beans is essential for animal feed to expand poultry and fish farming to improve nutrition of low-income households.

An inquiry in 2024 by the Competition Authority of Kenya into animal feed identified obstacles in cross-border markets. The government opened up to soymeal imports from India to provide an alternative source and prices fell 20% in early 2025. Kenya is surrounded by countries that could and should be ramping up their own soybean production for expanded regional trade.

SolutionsIt bears repeating, east and southern Africa is the best area in the world to expand production of crops such as maize and soybean. The expansion would mean some of the lowest instead of the highest prices internationally and lay the foundation for downstream food processing.

The G20 ministers adopted the African philosophy of ubuntu, “I am because you are”, to envision food systems which recognise interdependence across communities, borders and generations.

It means a complete change from the current situation where countries practise “beggar thy neighbour” policies such as restricting trade when a neighbour is facing drought.

Market monitoring is a crucial part of rebuilding cooperation instead of division. The G20 points to the Agricultural Market Information System, an inter-agency platform to enhance food market transparency and policy response for food security launched in 2011 by G20 Ministers of Agriculture. The platform provides data on global food supply and prices. But the platform has no data on markets in sub-Saharan African countries except South Africa and Nigeria.

Without data, countries can’t address hunger and food insecurity. As shocks become more frequent and severe, this work needs to massively accelerate.

Our analysis of market outcomes and factors influencing prices points to a straightforward set of measures.

First, regional monitoring of food markets is essential to guard against market manipulation. Monitoring needs to cover pricing, trade flows and associated barriers, and changes in market structure for a more robust understanding of markets. It is especially important in light of climate-related shocks.

Second, improved governance of food value chains to address food security and supply needs to be accompanied by enforcement of clear rules against abuse of company power that transcends national borders. Competition authorities need to be effective referees.

Third, investments in infrastructure such as storage facilities and appropriate irrigation are essential to adapt to the effects of climate change, improve resilience and yields, and safeguard against volatile markets.

Fourth, financing should be mobilised for small and medium scale producers who form the backbone of agricultural production across the region.

A critical question, of course, is about the political will to take these measures forward.

Grace Nsomba acknowledges funding from the Shamba Centre for Food and Climate, Open Society Foundation, COMESA Competition Commission and Competition Commission South Africa for research on food and agriculture markets.

Simon Roberts acknowedges funding from the Shamba Centre for Food and Climate, Open Society Foundation, COMESA Competition Commission and Competition Commission South Africa for research on food and agriculture markets.

Grattan on Friday: Master communicator vs master tactician, the race between Chalmers and Burke

It was a classic “old bull” versus “young bull” struggle, and the old bull showed he had life in him yet.

Paul Keating was only one among many critics of the controversial aspects of Treasurer Jim Chalmers’ proposed superannuation tax changes. But as the father of national superannuation, the former treasurer enjoyed a special advantage when it came to lobbying.

Keating wasn’t going to be denied. He was in Prime Minister Anthony Albanese’s ear as well as badgering Chalmers. (Chalmers revealed he’d spoken half a dozen times with Keating just in the second half of last week when recrafting the superannuation package.)

Albanese, naturally cautious when pressure mounts on unpopular measures, drove the retreat announced by Chalmers on Monday. The reworked package (which still faces the Senate hurdle) increases the tax on big superannuation balances but drops the earlier plan to tax unrealised capital gains. And unlike the original one, it also includes indexation for affected balances.

After the victory, Keating issued a statement lavishing praise on Chalmers for the revised version. But it couldn’t alter the reality. After months of limbo, Chalmers had been publicly humiliated.

The revamped arrangements, which involve separate higher tax rates for balances over $3 million and $10 million respectively, plus more help with superannuation for low income earners, do make the super system fairer. And they bring some savings for the budget, albeit less than the original plan, which was to take effect sooner.

Chalmers tried to put the best spin on it, denying he had been rolled by Albanese. But this has been one of the most difficult weeks of his time as treasurer.

In the public’s mind, Chalmers is the obvious next Labor leader. After the huge election victory, Albanese might look like going on forever, but politics doesn’t often work like that. Many in Labor, if pushed, would predict the prime minister will win the next election and then depart sometime during his third term.

Chalmers will want, and need, this second term to be a showcase for his credentials for future leadership.

A few years ago, Labor’s talked-about potential leadership field was quite extensive: Chris Bowen, Tanya Plibersek and Jason Clare were among those on the list. Now it has narrowed, probably to Chalmers, Tony Burke and Richard Marles.

Of these, Chalmers, 47, and Burke, 55, are considered (at this stage) the leading contenders (although Marles certainly hasn’t given up). The two men are a study in contrasts, and the contest between them for long-term ascendancy may be tighter than it appears at first glance.

While Chalmers was licking his wounds this week, Burke was appearing at the National Press Club, announcing new measures to crack down on crypto crime.

Looking to the top job, Burke has the advantage of being from the factionally-strong NSW right. He is close to Albanese, who’s from the NSW left. In that state, right and left can make common cause when they choose; the right helped deliver support to Albanese for the leadership in 2019.

For most of Labor’s first term, Burke was in the workplace relations portfolio, where he delivered in spades to the union movement. His own origins are in the powerful Shop, Distributive and Allied Employees’ Association (SDA).

Later he was moved to his present post of home affairs minister, after the government found itself in a world of trouble over the former immigration detainees, released after a High Court judgement.

Burke’s performance in this role has been politically masterful. One of his advantages for Albanese is his skill with the broom – he’s the man to clean up messes.

He pulled off an extraordinary deal to relocate the ex-detainees to Nauru. He sought a way to minimise angst over the return of Islamic State brides (though he was partly thwarted by the fact Senate estimates hearings were on last week, giving more opportunity for questioning).

Burke has rebuilt the home affairs behemoth, which Labor, having condemned its reach in opposition, had earlier substantially dismantled. ASIO, the Australian Federal Police and other agencies are back under the home affairs minister. Burke told the National Press Club on Thursday, “when we have a convergence of threats we need to have a convergence of protection”.

Burke is also Leader of the House of Representatives, a position that both gives him power to maximise Labor’s parliamentary advantages, and also provides routine contact with caucus members, a chance to win friends for the future.

Burke has less of a presence in the public market place than Chalmers, who is (and seeks to be) constantly in the media.

Like Burke, Chalmers is from the right but coming from Queensland means he has a smaller base. If Chalmers is eventually to reach the leadership, he must rely on building a reputation as a reformer and on his sales skills.

But just how much reform will he be able to produce?

Chalmers made it clear after the economic roundtable that he is looking to tax reform, which was supported in broad terms by many participants. The knock he took on superannuation, however, will reinforce his fear Albanese won’t be up for major tax changes, which would likely cost the government political capital. Labor almost certainly cannot be defeated at the 2028 election, but Albanese will want to keep intact as much of the majority as possible.

The roundtable was a pointer to Chalmers’ ambition generally. Albanese announced it as a roundtable on “productivity”; Chalmers renamed it as one on “economic reform” and put in a tremendous effort to have ministers involved and to achieve results. At the end of the three days he announced a long list of initiatives centring particularly on reducing red tape and clearing bottlenecks. But many were speeding up existing efforts or otherwise incremental. In one area, a new road user charge, progress appears to going slowly, despite Chalmers hoping for fast action.

There’s general agreement in Labor that Chalmers is the government’s best communicator. But insiders watching this race know Burke is the master tactician. Journalist Phillip Coorey recently described him as “probably one of the best practitioners of the dark arts”. Burke may not wear his ambition on his sleeve to the extent Chalmers does, but it burns intensely and he is not to be underestimated.

Michelle Grattan does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

With delay of pension reform, Prime Minister Sébastien Lecornu puts France’s Socialist Party back in the spotlight

In his policy speech to lawmakers in the National Assembly on Tuesday, Prime Minister Sébastien Lecornu – who was reappointed by President Emmanuel Macron on Friday after submitting his resignation just days before – announced the suspension of pension reform, which a previous government forced into law without a vote in 2023. The reform raised the retirement age from 62 to 64, and also raised, depending on one’s year of birth, the number of working years required to 43. It had sparked mass protests even before it became law.

Lecornu’s announcement was key to obtaining an agreement from France’s once-mighty Socialist Party, which has 69 members and affiliated members in the 577-member Assembly, that it would not support a potential vote of no-confidence. How will the Socialists position themselves as the government’s finance bill comes up for debate? Is a parliamentary logic of consensus gaining ground? An interview with political scientist and French constitutional expert Benjamin Morel.

The Socialist Party (PS) has agreed not to back a no-confidence vote. Is Lecornu’s government guaranteed to remain in power?

Benjamin Morel: It takes 289 MPs not to vote in favour of the motion of no-confidence for the government to remain in power. At this stage, a motion of no-confidence is unlikely due to the number of political groups that have given instructions not to vote in favour of it. However, some groups, notably LR (Les Républicains, a right-wing party) and PS, are prone to dissent, and there are unknowns on the side of the non-attached members of LIOT (Libertés, indépendants, Outre-mer et territoires, a centrist group). Will there be more than 20 dissidents, which would allow the government to be censured? It’s not impossible, but it is unlikely.

Is a dissolution of parliament, which would be effected by President Emmanuel Macron, also unlikely?

B.M.: If the Lecornu government does not immediately lose a confidence vote, dissolution is probably out of the question. Indeed, if dissolution were to take place in November or early December, there would no longer be any MPs in the National Assembly to vote on the budget or pass a special law allowing revenue to be collected: this would then be a major institutional problem. If dissolution were to occur later – in the spring – it would take place at the same time as municipal elections, which PS and LR mayors would oppose because they could suffer from a “nationalisation” of local contests. Dissolution after the municipal elections? We would be less than a year away from the presidential election, and dissolution would be a considerable hindrance to Macron’s successor. For all these reasons, it is quite likely that dissolution will be ruled out.

If Lecornu’s government does not immediately lose a confidence vote, the next step will be a vote on the budget. What are the different scenarios for the budget’s adoption? What position will the PS take?

B.M.: Lecornu has announced that he will not invoke Article 49.3 (the constitutional rule that allows the government to pass a law without a vote) for the budget: this means that the budget can only be adopted after a positive vote by a majority of MPs, including the Socialist Party’s. However, we can expect the Senate, which has a right-wing majority, to push for a more austere budget before it goes to a joint committee and back to the Assembly. For the budget to be adopted, the Socialists would therefore have to vote in favour of a text that they do not really agree with, under pressure from the rest of the left, just a few months before the municipal elections. Lecornu’s general policy speech was considered a triumph for Socialist Party leader Olivier Faure and the PS. This is true, but the PS is now in a very complicated political situation.

The second scenario is that of a rejected budget and a government resorting to special laws. The problem is that these laws do not allow for all public investments to be made, which would have real economic consequences. In this case, a budget would have to be voted on at the beginning of 2026 with an identical political configuration (in the Assembly) and municipal elections approaching, which will further exacerbate the situation.

The final scenario is that after 70 days, Article 47 of the Constitution, noting that parliament has not taken a decision, allows the government to execute the budget by decree. There is uncertainty regarding Article 47 and the decrees, as they have never been used. Legal experts think that it is the last budget adopted that is submitted by decree – so, in principle, it would be the Senate’s budget, probably a very tough one – with the possible exclusion of funds earmarked for the suspension of pension reform.

Ultimately, the Socialists could face a real strategic dilemma: adopt a budget they will find difficult to support, bear the cost of special laws, or accept the implementation by decree of a budget drafted by the Senate’s right wing. All of this will likely lead to further crises.

How can we understand the change of direction by the Lecornu government, which is moving from an alliance with LR to an agreement with the PS?

B.M.: The PS became vital because the Rassemblement National (the far-right National Rally, or RN) entered into a logic where it wanted a dissolution in the hope of obtaining an absolute majority in the Assembly. As a result, the PS became the only force that allowed Lecornu to remain in place. The PS was able to take full advantage of this situation. Another factor in the PS’s favour is recent polls showing that, in the event of a dissolution, the Socialists would do well while the centre bloc would be left in tatters. This fundamentally changes the balance of power. To avoid losing a confidence vote and then facing dissolution, the government had to offer a big concession: the suspension of the pension reform.

How should we interpret this agreement between the central bloc and the PS? Is the parliamentary logic of consensus finally gaining ground?

B.M.: This political development is not based on parliamentary logic but on a balance of power. In a parliamentary system, the president does not pull a prime minister out of a hat, saying ‘it’s him and no one else’. He looks within parliament for someone capable of forming a majority. Once this majority has been found, a programme is drawn up and finally a government is appointed. The logic of consensus would have required a comprehensive agreement, a joint government programme between LR and PS. This is not the case at all.

Macron is not really asking Lecornu to find a majority; he is asking him to try not to lose a confidence vote, even though this PM is supported by only a minority of MPs – just under 100, from (central bloc parties) Renaissance and MoDem – which is unheard of in any parliamentary democracy. The result is that the balance of power is extraordinarily fragile and crises are recurrent. However, these obstacles will have to be overcome, and we will have to get used to relative majorities, because the polls do not necessarily suggest that a new majority would emerge in the event of a dissolution of parliament or even a new presidential election.

Interview conducted by David Bornstein.

A weekly e-mail in English featuring expertise from scholars and researchers. It provides an introduction to the diversity of research coming out of the continent and considers some of the key issues facing European countries. Get the newsletter!

Benjamin Morel ne travaille pas, ne conseille pas, ne possède pas de parts, ne reçoit pas de fonds d'une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n'a déclaré aucune autre affiliation que son organisme de recherche.

October 15, 2025

Some US protein powders contain high levels of lead. Can I tell if mine is safe?

whitebalance.space/Getty Images

whitebalance.space/Getty ImagesThis week, the United States non-profit Consumer Reports released its investigation testing 23 protein powders and ready-to-drink shakes from popular brands to see if they contained heavy metals.

More than two-thirds of the products contained more lead in a recommended serving size serving than the Californian guidlines recommend in a day: 0.5 micrograms (mcg or µg).

Protein powders and shakes are most commonly used to build muscle. But some people may use it in a weight-loss program as a meal replacement, or to gain back weight lost after an illness or injury.

Some products Consumer Reports tested were plant-based, some were labelled as organic and some used animal and dairy-based protein. Only one product didn’t contain detectable levels of lead.

So what does this mean for people who use protein powder? And what’s the situation in Australia?

Lead has been found in protein powder beforeConsumer Reports found lead levels increased since its last report in 2010. One product contained twice as much lead per serving than the worst performer in 2010.

A separate investigation in 2018 which analysed 130 protein powders available on Amazon found 70% had heavy metals in them.

Another analysis of 36 protein powders in 2021 found lead levels ranged from 0.8-88.4 mcg per kilogram of product. Consuming a single 20 gram serve a day, would mean a range of intake of 0.016 mcg to 1.77 mcg.

How does lead get into these products?Lead comes from both natural sources (such as volcanic activity and chemical weathering of rocks) and human-made sources (such as leaded petrol, industrial processes and paint). This results in crops absorbing lead and the metal entering the food and water supply.

In US government testing from 2014 to 2016, 27% of all food samples (2,923) had lead detected in them.

In Australia, testing in 2019 found that of the 508 food samples, 15% had detectable levels of lead. Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ) modelling suggests this would result in an average lead intake of 0.018–0.16 mcg per kg a day across different age groups. For a 70kg person, this would range from 1.26 to 11.2 mcg per day from food and drinks.

Lead can also be inhaled as dust from industrial processes such as mining smelters or by inhaling (or licking) fragments of lead-rich paint when handling old lead toys or other lead equipment, or from consuming or coming into contact with contaminated water or soil.

How can lead affect your health?Lead provides no health benefits. It’s harmful to the body and can damage nearly every organ system.

Its greatest impact is on the brain and nervous system. For children, this can lead to impaired cognitive and physical development, learning disabilities and behavioural problems.

With high levels of lead exposure, adults are at increased risk of anaemia, joint pain, kidney damage and nerve damage leading to tingling, numbness and muscle weakness.

During pregnancy, lead can be transmitted to the fetus, leading to complications such as premature birth, low birth weight and developmental issues in the baby. It’s also a concern for breastfeeding mothers, as some lead can be transmitted through the breast milk.

Lead has also been listed as a possible carcinogen, or cause of cancer, by International Agency for Research on Cancer.

As levels increase in the blood, health concerns grow. Very high levels in the blood (above 120 mcg per decilitre) can cause death.

What do other guidelines say is a safe level of lead?Australia’s National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) concludes there is no set safe level of lead in your diet. You should aim to consume as little as possible to avoid health impacts.

The NHRMC recommends blood levels, which take into account all exposures, should be below 5 mcg per decilitre of blood. (But Australia doesn’t have a daily limit.)

In 2022, the US Food and Drug Administration updated its maximum safe dietary lead levels to 2.2 mcg a day for children and 8.8 mcg a day for women of childbearing age. This is much higher than the Californian levels Consumer Reports used.

Using the FDA levels, all the products Consumer Reports tested could be consumed daily for adults – but this doesn’t account for exposure from other foods or the environment.

Should we be concerned in Australia?Most of the products Consumer Reports tested are available for purchase online, and may possibly be available in stores.

There is no data on lead levels in protein powder sourced and manufactured in Australia.

So there is no way of knowing whether your protein supplement has lead in it, unless you get a chemical analysis done through an accredited laboratory as Consumer Reports did.

So should I limit my intake?Probably, but not just because of concerns about lead.

We simply don’t know how much lead is in each scoop of protein powder, so it’s difficult to make recommendations about whether these products are safe to use daily. Levels will vary between products and even between containers. Occasional use is likely to be safe, but using it daily or more often could lead to unsafe intakes of lead.

It’s also important to remember that your blood levels will also be affected by environmental exposures and other foods.

But most of us don’t need extra protein, even if we’re training. Around 99% of Australians already meet their protein requirements.

It’s better to consume protein from whole foods, and you’ll get the benefits of other nutrients as well:

dairy products also contain calcium and vitamin B12fermented dairy such as yoghurt and cheese also contains probioticsfish has omega-3 fatsred meat contains iron and zinclentils, beans and nuts give you antioxidants and fibre.All these nutrients are equally important for our good health and are less likely to be concentrated sources of heavy metals such as lead.

Evangeline Mantzioris is affiliated with Alliance for Research in Nutrition, Exercise and Activity (ARENA) at the University of South Australia. Evangeline Mantzioris has received funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council, and has been appointed to the National Health and Medical Research Council Dietary Guideline Expert Committee.

Billions in private cash is flooding into fusion power. Will it pay off?

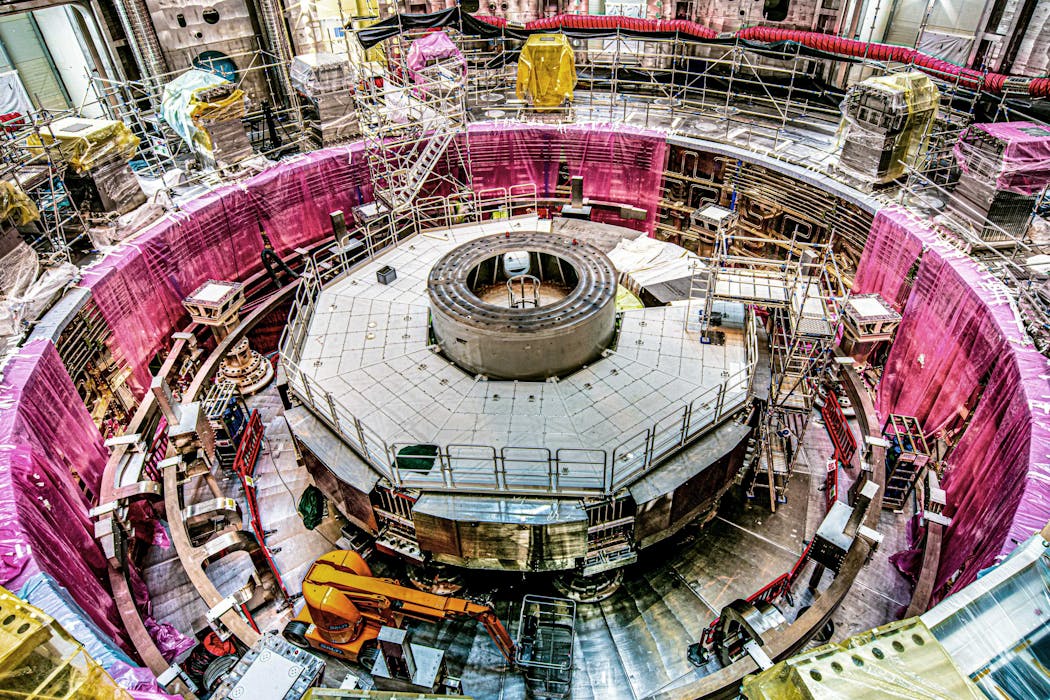

The ITER fusion reactor under construction in 2021. Jean-Marie Hosatte / Getty Images

The ITER fusion reactor under construction in 2021. Jean-Marie Hosatte / Getty ImagesOver the past five years, private-sector funding for fusion energy has exploded. The total invested is approaching US$10 billion (A$15 billion), from a combination of venture capital, deep-tech investors, energy corporations and sovereign governments.

Most of the companies involved (and the cash) are in the United States, though activity is also increasing in China and Europe.

Why has this happened? There are several drivers: increasing urgency for carbon-free power, advances in technology and understanding such as new materials and control methods using artificial intelligence (AI), a growing ecosystem of private-sector companies, and a wave of capital from tech billionaires. This comes on the back of demonstrated progress in theory and experiments in fusion science.

Some companies are now making aggressive claims to start supplying power commercially within a few years.

What is fusion?Nuclear fusion involves combining light atoms (typically hydrogen and its heavy isotopes, deuterium and tritium) to form a heavier atom, releasing energy in the process. It’s the opposite of nuclear fission (the process used in existing nuclear power plants), in which heavy atoms split into lighter ones.

Taming fusion for energy production is hard. Nature achieves fusion reactions in the cores of stars, at extremely high density and temperature.

The density of the plasma at the Sun’s core is 150 times that of water, and the temperature is around 15 million degrees Celsius. Here, ordinary hydrogen atoms fuse to ultimately form helium.

However, each kilogram of hydrogen produces only around 0.3 watts of power because the “cross section of reaction” (how likely the hydrogen atoms are to fuse) is tiny. The Sun, however, is enormous and massive, so the total power output (1026 watts) and the burn duration (10 billion years) are astronomical.

Fusion of heavier forms of hydrogen (deuterium and tritium) has a much higher cross section of reaction, meaning they are more likely to fuse. The cross-section peaks at a temperature ten times hotter than the core of the Sun: around 150 million °C.

The only way to continuously contain the plasma at temperatures this high is with an extremely strong magnetic field.

Increasing the outputSo far, fusion reactors have struggled to consistently put out more energy than is put in to make the fusion reaction happen.

The most common design for fusion reactors uses a toroidal, or donut-like, shape.

The best result using deuterium–tritium fusion in the donut-like “tokamak” design was achieved at the European JET reactor in 1997, where the energy output was 0.67 times the input. (However, the Japanese JT-60 reactor has achieved a result using only deuterium that suggests it would reach a higher number if tritium were involved.)

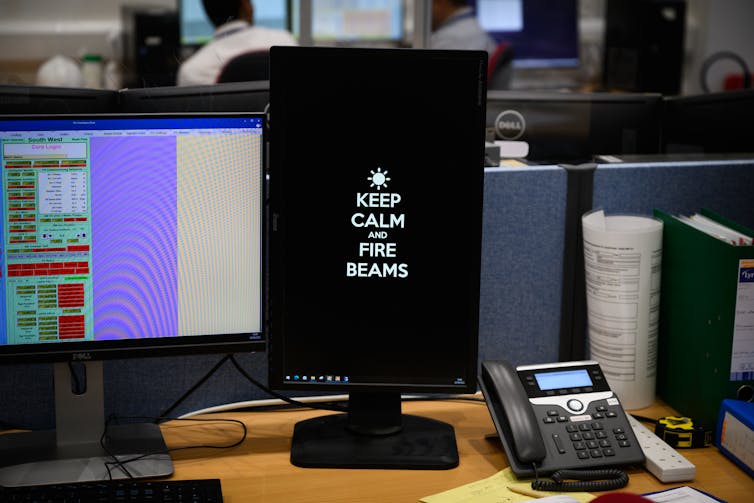

The control room of the JET fusion experiment in Abingdon, England. Leon Neal / Getty Images

The control room of the JET fusion experiment in Abingdon, England. Leon Neal / Getty Images Larger gains have been demonstrated in brief pulses. This was first achieved in 1952 in thermonuclear weapons tests, and in a more controlled manner in 2022 using high-powered lasers.

The ITER projectThe public program most likely to demonstrate fusion is the ITER project. ITER, formerly known as the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor, is a collaborative project of more than 35 nations that aims to demonstrate the scientific and technological feasibility of fusion as an energy source.

ITER was first conceived in 1985, at a summit between US and Soviet leaders Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev. Designing the reactor and selecting a site took around 25 years, with construction commencing at Cadarache in southern France in 2010.

The project has seen some delays, but research operations are now expected to begin in 2034, with deuterium–tritium fusion operation slated for 2039. If all goes according to plan, ITER will produce some 500 megawatts of fusion power, from as little as 50MW of external heating. ITER is a science experiment, and won’t generate electricity. For context, however, 500MW would be enough to power perhaps 400,000 homes in the US.

New technologies, new designsITER uses superconducting magnets that operate at temperatures close to absolute zero (around –269°C). Some newer designs take advantage of technological advances that allow for strong magnetic fields at higher temperatures, reducing the cost of refrigeration.

One such design is the privately owned Commonwealth Fusion System’s SPARC tokamak, which has attracted some US$3 billion in investment. SPARC was designed using sophisticated simulations of how plasma behaves, many of which now use AI to speed up calculations. AI may also be used to control the plasma during operations.

Commonwealth Fusion Systems’ pilot fusion plant under construction. Commonwealth Fusion Systems

Commonwealth Fusion Systems’ pilot fusion plant under construction. Commonwealth Fusion Systems Another company, Type I Energy, is pursuing a design called a stellarator, which uses a complex asymmetric system of coils to produce a twisted magnetic field. In addition to high-temperature superconductors and advanced manufacturing techniques, Type I Energy uses high-performance computing to optimally design machines for maximum performance.

Both companies claim they will roll out commercial fusion power by the mid-2030s.

In the United Kingdom, a government-sponsored industry partnership is pursuing the Spherical Tokamak for Energy Production, a prototype fusion pilot plant proposed for completion by 2040.

Meanwhile, in China, a state-owned fusion company is building the Burning Plasma Experimental Superconducting Tokamak, which aims to demonstrate a power gain of five. “First plasma” is slated for 2027.

When?All projects planning to make power from fusion using donut-shaped magnetic fields are very large, producing on the order of a gigawatt of power. This is for fundamental reasons: larger devices have better confinement, and more plasma means more power.

Can this be done in a decade? It won’t be easy. For comparison, design, siting, regulatory compliance and construction of a 1GW coal-fired power station (a well understood, mature, but undesirable technology) could take up to a decade. A 2018 Korean study indicated the construction alone of a 1GW coal-fired plant could take more than 5 years. Fusion is a much harder build.

Private and public-private partnership fusion energy projects with such ambitious timelines would have high returns – but a high risk of failure. Even if they don’t meet their lofty goals, these projects will still accelerate the development of fusion energy by integrating new technology and diversifying risk.

Many private companies will fail. This shouldn’t dissuade the public from supporting fusion. In the long term, we have good reasons to pursue fusion power – and to believe the technology can work.

Matthew Hole receives funding from the Australian government through the Australian Research Council and the Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation (ANSTO), and the Simons Foundation. He is also affiliated with ANSTO, the ITER Organisation as an ITER Science Fellow, and is Chair of the Australian ITER Forum.

The climate crisis is fuelling extreme fires across the planet

We’ve all seen the alarming images. Smoke belching from the thick forests of the Amazon. Spanish firefighters battling flames across farmland. Blackened celebrity homes in Los Angeles and smoked out regional towns in Australia.

If you felt like wildfires and their impacts were more extreme in the past year – you’re right. Our new report, a collaboration between scientists across continents, shows climate change supercharged the world’s wildfires in unpredictable and devastating ways.

Human-caused climate change increased the area burned by wildfires, called bushfires in Australia, by a magnitude of 30 in some regions in the world. Our snapshot offers important new evidence of how climate change is increasing the frequency and severity of extreme fires. And it serves as a stark reminder of the urgent need to rapidly cut greenhouse gas emissions.

The evidence is clear – climate change is making fires worse.

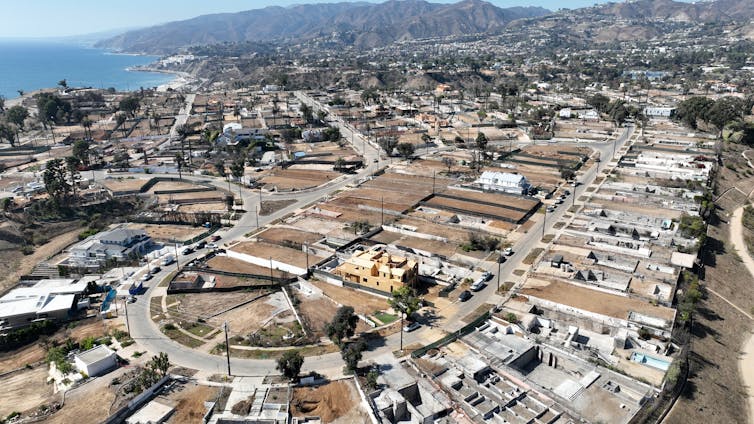

A view of the Palisades fire zone in Los Angeles, where climate change fuelled the fires in January. Allen J. Schaben/Getty Clear pattern

A view of the Palisades fire zone in Los Angeles, where climate change fuelled the fires in January. Allen J. Schaben/Getty Clear patternOur study used satellite observations and advanced modelling to find and investigate the causes of wildfires in the past year. The research team considered the role that climate and land use change played, and found a clear interrelationship between climate and extreme events.

Regional experts provided local input to capture events and impacts that satellites did not pick up. For Oceania, this role was played by Dr Sarah Harris from the Country Fire Authority and myself.

In the past year, a land area larger than India – about 3.7 million square kilometres – was burnt globally. More than 100 million people were affected by these fires, and US$215 billion worth of homes and infrastructure were at risk.

Not only does the heating climate mean more dangerous, fire-prone conditions, but it also affects how vegetation grows and dries out, creating fuel for fires to spread.

In Australia, bushfires did not reach the overall extent or impact of previous seasons, such as the Black Summer bushfires of 2019–20. Nonetheless, more than 1,000 large fires burned around 470,000 hectares in Western Australia, and more than 5 million hectares burned in central Australia. In Victoria, the Grampians National Park saw two-thirds of its area burned.

In the United States, our analysis showed the deadly Los Angeles wildfires in January were twice as likely and burned an area 25 times bigger than they would have in a world without global warming. Unusually wet weather in Los Angeles in the preceding 30 months contributed to strong vegetation growth and laid the foundations for wildfires during an unusually hot and dry January.

In South America, fires in the Pantanal-Chiquitano region, which straddles the border between Brazil, Bolivia and Paraguay, were 35 times larger due to climate change. Record-breaking fires ravaged parts of the Amazon and Congo, releasing billions of tonnes of carbon dioxide.

Protestors march for climate justice and against wild fires affecting the entire country in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Faga Almeida/Getty Not too late

Protestors march for climate justice and against wild fires affecting the entire country in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Faga Almeida/Getty Not too lateIt’s clear that if global greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise, more severe heatwaves and droughts will make landscape fires more frequent and intense worldwide.

But it’s not too late to act. We need stronger and faster climate action to cut fossil fuel emissions, protect nature and reduce land clearing.

And we can get better at responding to the risk of fires, from nuanced forest management to preparing households and short and long-term disaster recovery.

There are regional differences in fires, and so the response also need to be local. We should prioritise local and regional knowledge, and First Nations knowledge, in responding to bushfire.

Action at COP30Fires emitted more than 8 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide in 2024–25, about 10% above the average since 2003. Emissions were more than triple the global average in South American dry forests and wetlands, and double the average in Canadian boreal forests. That’s a deeply concerning amount of greenhouse pollution. The excess emissions alone exceeded the national fossil fuel CO₂ emissions of more than 200 individual countries in 2024.

Next month, world leaders, scientists, non-governmental organisations and civil society will head to Belem in Brazil for the United Nations annual climate summit (COP30) to talk about how to tackle climate change.

The single most powerful contribution developed nations can make to avoid the worst impacts of extreme wildfires is to commit to rapidly cutting greenhouse gas emissions this decade.

Hamish Clarke receives funding from the Westpac Scholars Trust (HC) and the Australian Research Council via an Industry Fellowship IM240100046. He is a member of the International Association of Wildland Fire, the Australian Meteorological and Oceanographic Society and the Australian Science Communicators, and a member of the Oceania Regional Committee of the IUCN Commission on Ecosystem Management.

What a surprise spike in the unemployment rate means for interest rates and the economy

The rate of unemployment in Australia is on the rise again. Official labour force data released on Thursday shows that in the month to September, Australia’s seasonally adjusted unemployment rate jumped from 4.3% to 4.5%.

That’s the highest rate since November 2021. The surprise jump strengthens the case for the Reserve Bank of Australia to cut the official cash rate in November.

Back in November last year, the seasonally adjusted rate of unemployment was 3.9%. It has now been above 4% for ten consecutive months, and has only been going in one direction: up.

What could this mean for interest rates?In its recent decisions, the Reserve Bank’s monetary policy board has jumped at any signs of higher price inflation. But it has retained a favourable outlook on labour market conditions.

In its most recent September decision, the board stated:

labour market conditions have been broadly steady in recent months and remain a little tight.

Such an outlook does not seem an option in light of today’s unemployment numbers.

The Reserve Bank has a full employment mandate to achieve “the maximum level of employment consistent with low and stable inflation”.

The mandate doesn’t put a specific numerical rate on this full employment goal. However, the rate of unemployment is now well above any credible estimate of full employment.

Employment growth is slowingThe reason why the rate of unemployment is rising is not hard to spot. Employment growth is slowing.

In 2024, my calculations based on the official labour force data show an average of 32,600 extra people became employed each month, compared with an extra 33,900 looking for work.

With growth in employment and the labour force relatively balanced, the rate of unemployment remained stable.

So far in 2025, each month only an average of 12,900 extra people have moved into employment.

The number of people looking for work has responded to the weaker labour market conditions, also growing less each month than in 2024, by 22,100 on average.

But unemployment is rising because the increase in the number of people looking for work in 2025 has been much bigger than the increase in employment.

A cooling jobs marketNo matter which statistic you look at, my analysis of the official labour force data reveals the signs of a weakening labour market are clear to see.

Monthly hours worked grew on average by 0.27% each month in 2024, but only 0.04% so far in 2025.

In 2024, the total stock of jobs rose by 351,600. In the first six months of 2025, it grew by just 44,100.

And the proportion of people who have jobs, but want to work more hours, has increased from 9.9% to 10.4% since the end of 2024.

Government spendingThe reason employment growth is slowing is not what might have been expected – but is even more worrying.

Since about mid-2021, employment growth in Australia has been propped up by a fast pace of job creation in what is known as the non-market sector, which consists of:

health care and social assistance education and training public administration and safety.That growth has come about as the federal government has pushed for improvements in the quality of government services, and expanded the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) and childcare services.

It has been expected for some time that eventually, the rate of increase in government spending on services would slow. That would in turn cause growth in non-market employment and total employment to slacken.

What’s really driving the trend?However, that is not what has caused the slower employment growth in 2025.

In fact, today’s data release shows that growth in total hours worked in the non-market sector has continued at pretty much the same pace as in previous years.

Instead, the drop-off in total hours worked has been due to employment in the market sector declining.

Private employers are responding to what they see as weaker economic conditions, by reducing the rate at which they are adding new jobs.

This is a further undeniable sign of a weakening labour market.

Jeff Borland has received funding from the Australian Research Council.

How voluntary assisted dying in the NT would be different to down south

Felix Cesare/Getty

Felix Cesare/GettyVoluntary assisted dying is being debated in the Northern Territory (NT) parliament this week.

The NT is now the last jurisdiction in Australia without voluntary assisted dying laws. But it wasn’t always this way. Once, the NT was a pioneer in legalising assisted dying.

Here’s what’s happened since then, and why this time, the conversation looks very different.

A brief historyIt’s been nearly 30 years since the NT made history as the first jurisdiction in the world to legalise assisted dying.

In 1995, the NT passed the Rights of the Terminally Ill Act, allowing terminally ill adults to choose a medically assisted death. Four people used the law.

But the Commonwealth overturned it in 1997, removing the power of the NT and Australian Capital Territory to legislate on the issue.

It’s almost three years since the Commonwealth restored the NT’s right to make its own voluntary assisted dying laws.

Now, every other jurisdiction in Australia has legalised voluntary assisted dying, most recently the ACT in 2024.

Why the NT is uniqueThe NT’s context is unlike anywhere else in Australia. It is vast and sparsely populated. It is home to more than 250,000 people, spread across an area more than five times the size of the United Kingdom.

About 30% of Territorians identify as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander, and about three-quarters of Aboriginal Territorians live in remote or very remote communities.

Health-care access is limited. Many communities rely on small remote health clinics that face chronic staff shortages and high turnover.

Northern Territory residents, collectively, suffer from disease and die prematurely about 58% more than the national average. The number of years of life lost by Indigenous Territorians as a result of ill health, poor nutrition and other causes is 3.5 times the number for non-Indigenous residents.

Against this backdrop, introducing voluntary assisted dying raises complex questions. How can Territorians exercise equal choice at the end of life – either with each other or in comparison with Australians in other jurisdictions – when access to doctors, nurses, interpreters, and even reliable internet varies so widely?

Telehealth is a major barrierUnder the Commonwealth criminal code, using “a carriage service” such as a phone or the internet to discuss or arrange assisted dying remains illegal, as it falls under prohibitions on suicide-related material.

A federal court confirmed in 2023 this restriction applies to voluntary assisted dying. For people in remote NT communities, where the nearest doctor might be hundreds of kilometres away, this makes equitable access almost impossible.

Until this issue is resolved, voluntary assisted dying in the NT and elsewhere in Australia can only occur through face-to-face consultations. This is an unrealistic expectation for many rural, remote and frail residents, when telehealth is an accepted part of health care in other areas.

Aboriginal perspectivesViews among Aboriginal Territorians on voluntary assisted dying are diverse and deeply nuanced, as we heard during consultations led by the NT Voluntary Assisted Dying Independent Expert Advisory Panel.

Many Aboriginal organisations told the panel they supported equitable access to all end-of-life services. Others raised cultural, spiritual and religious concerns.

As one community-controlled organisation told the panel:

People might engage better with health services knowing that it could be an option to come back [to Country].

Others expressed unease, noting that assisted dying could conflict with cultural or religious beliefs. One Aboriginal organisation told the panel:

For the older generation, [who have] one foot in the Dreamtime and another in religion, this would probably be really difficult.

In research published earlier this year in the Medical Journal of Australia, we expand on such issues and highlight an important difference in world views.

Western medical models emphasise individual autonomy, while Aboriginal decision-making often happens collectively, in kinship networks.

Voluntary assisted dying laws that require a person to act independently and without influence may not easily align with cultural norms around family consultation and shared decision-making.

Cultural safety and co-design“Cultural safety” is care that Aboriginal patients and communities define as safe. This will be essential if voluntary assisted dying becomes law. However, it means more than translating forms or providing interpreters. It involves building trust, recognising power imbalances, and ensuring Aboriginal voices are central to governance and service delivery.

The Legal and Constitutional Affairs Committee report tabled this month recommends voluntary assisted dying. Like our earlier research, the report calls for co-design with Aboriginal organisations to ensure culturally safe implementation, ongoing consultation, and appropriate training for clinicians.

If the NT does proceed, success will depend on Aboriginal leadership in governance, properly resourced services, and flexibility to adapt as communities engage with the law in their own way.

Voluntary assisted dying in the NT cannot simply be imported from elsewhere. It must be built for the Territory, and with the Territory.

If this article raises issues for you, or if you’re concerned about someone you know, call Lifeline on 13 11 14 or Griefline on 1300 845 745.Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people can also contact13YARN on 13 92 76.

Geetanjali (Tanji) Lamba is a public health physician at NT Health. She was a member of the Northern Territory Chief Minister’s Voluntary Assisted Dying Independent Expert Advisory Panel and medical advisor to the Legal and Constitutional Affairs Committee Inquiry into voluntary assisted dying. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of her employers or the NT government.

Kane Vellar works at NT Health as a Staff Specialist in psychiatry, palliative care and psycho-oncology. He undertakes select in-patient private practice after hours with Healthscope at the Darwin Private Hospital. Kane Vellar was a member of the Northern Territory Chief Minister’s Voluntary Assisted Dying Independent Expert Advisory Panel and is a member of the Australian Indigenous Doctors' Association. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of his employers or the NT government.

Paul Komesaroff has received funding from the NHMRC. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of his employer.

As Gaza starts to rebuild, what lessons can be learned from Nagasaki in 1945?

At first, there might not seem to be any immediate similarities between a devastated Nagasaki after the US atomic bombing in 1945 and Gaza today, aside from massive destruction.

But in considering Gaza’s recovery from war – should the current ceasefire hold – much may be gleaned from Nagasaki’s experience and how it managed the painful process of starting over and rebuilding from virtually nothing.

Damage and destructionThe estimates of those killed from the atomic bombings in 1945 range widely from 70,000–140,000 at Hiroshima and 40,000–70,000 at Nagasaki.

In Gaza, the Palestinian health authorities say more than 67,000 Palestinians have died, with many more perhaps buried in the rubble.

In 1945, the US Army dropped an atomic bomb close to the centre of Hiroshima. But in Nagasaki’s case three days later, the plutonium bomb fell a few kilometres to the north of the city in a suburb called Urakami.

The bombing destroyed an area that was socio-economically less well-off, which had an impact on Nagasaki’s recovery, compared with Hiroshima.

Many of those who lived there were minorities, including colonised Korean people, Catholics and outcasts known as buraku.

And just as in Gaza, much of the city infrastructure was decimated. An atomic archive estimates that in Nagasaki, around 61% of city structures were damaged in the bombing, compared with 67% in Hiroshima.

In Gaza, the United Nations Satellite Centre estimates 83% of structures have been damaged from Israeli bombing.

Recovering bodies in a war zoneThe aftermath of the bombing shows just how great the needs of the people were in Nagasaki. I conducted an oral history survey with bombing survivors between 2008 and 2016. Twelve of them – mostly children from Catholic families close to Ground Zero at the time of the bombing – detailed their experiences before and after.

After the bombing, many said the unburied dead was a confronting aspect, both physically and spiritually “dangerous”. One survivor, Mine Tōru, told me:

The dead bodies were piled in carts used for rubbish collection and dumped out in an outer area.

Barrels were placed at intersections for the collection of ashes and bones. Meanwhile, the occupying US Army cleared Urakami with bulldozers.

In Swedish journalist Monica Brau’s book, a man named Uchida Tsukasa remembered those bulldozers driving over the bones of the dead in the same way as sand or soil. When someone tried to take a photo, a soldier pointed his gun and threatened to confiscate the pictures. Brau argued that US censorship grossly impaired the recovery in Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

The clean-up and retrieval of human remains took time. Some six months after the bombing, bones were still being pulled out of the river by a Buddhist Ladies’ Association.

This process is beginning in Gaza today, too. According to news reports, scores of bodies have already been pulled from the rubble since the ceasefire took hold. Estimates suggest there could be as many as 14,000 bodies in the rubble, many of which will never be recovered.

The political challenges of rebuildingIn rehabilitating Gaza, those overseeing the process will also need to ensure the civil liberties of the poor – children and women, in particular – are not infringed upon.

In Nagasaki, some bomb survivors were forced to live in caves that had previously been bomb shelters, including three of those I interviewed.

Fukahori Jōji, who was 16 at the time of the bombing, lost his whole family, including three siblings and his mother. He told me that after the bombing, urban revitalisation and road-widening took over part of his family’s land.

Nagasaki officials were alleged to have used the reconstruction to “clean up” an outcast community.

A writer, Dōmon Minoru, explained how land was acquired compulsorily and cheaply by the council, forcing many residents out: “the Urakami burakumin (outcasts) were neutralised”.

Their landlords sold the land where they had lived and the Nagasaki Council even did away with the name, Urakami town.

As will likely be the case in Gaza, the people of Nagasaki also had to rebuild under an occupation.

US historian Chad Diehl’s powerful book about the rebuilding highlighted the “disconnect” between the American occupiers and Nagasaki residents.

The rebuilding took decades. Diehl explained there are two words for recovery often used in Nagasaki, saiken (reconstruction), which usually refers to the physical rebuilding, and fukkō (revival), which refers to wellbeing – psychological, social and physical.

The wellbeing recovery will surely take even longer than the rebuilding of the physical infrastructure in Gaza.

Hope among the rubbleAnother important aspect in recovery from war: the people need to have agency over the process. They shouldn’t just be thought of as survivors of a tragedy – they are integral to the revival of their communities.

Reiko Miyake, a teacher who was 20 at the time of the Nagasaki bombing, told me she returned to teaching at her elementary school a few months later. Only 100 of the 1,500 students at the school survived, and just 19 showed up on the first day.

As holders of memory, these people took on new roles of service for their communities. They were storytellers and rebuilders seeking hope in the face of unbearable loss and ongoing lament.

May such stories of the past encourage the difficult task of recovery in what is a bereft Gaza today.

Gwyn McClelland is the former recipient of a National Library of Australia Fellowship and a Japan Foundation Fellowship. He is the president of the Japanese Studies Association of Australia.

Optimising is just perfectionism in disguise. Here’s why that’s a problem

Willie B. Thomas/Getty

Willie B. Thomas/GettyIf you regularly scroll health and wellness content online, you’ve no doubt heard of optimising.

Optimisation usually means striving to make something the best it can be – the “optimal” version. A decade ago, it was mainly used to talk about workplace strategy, describing how a positive mindset might increase workers’ productivity.

But more recently it’s exploded in health messaging, not only among influencers and brands who want to sell us something, but also in government public health initiatives and research.

We’re now encouraged to optimise almost anything: our diets, sleep, brain health, gut biome, workout routines and even our lifespan.

This approach is often framed as the path to living a better, longer life, and it might seem empowering. But as a clinical psychologist and researcher, I believe the “optimisation mindset” has many of the hallmarks of perfectionism – a personality trait evidence links to poor mental health.

So, what do the two have in common? And what are some potentially healthier ways to approach things?

What we know about perfectionismWe don’t yet have much research about how adopting an optimisation mindset might affect mental health and wellbeing. But the negative effects of perfectionism are well established.

Perfectionism is a personality trait, meaning it’s stable over time. It involves the constant pursuit of high standards and achieving perfect outcomes. People with this trait are often very preoccupied by the fear of “getting it wrong”.

Perfectionism affects both men and women. It’s more common in people prone to anxiety, as well as high-achieving individuals such as students, athletes and academics.

People who have this trait are also more likely to have depression and low self-esteem.

And it’s one of the key features used to diagnose several mental health conditions, such as obsessive compulsive disorder, generalised anxiety disorder and eating disorders.

Many of the thought patterns and feelings that come with “optimising” resemble those in perfectionism. So while optimisation isn’t a personality trait like perfectionism, this mindset may still lead to worse mental health.

Striving to achieve an optimal diet or workout routine can make people very worried about getting it wrong. szjphoto/Getty What optimisation and perfectionism share

Striving to achieve an optimal diet or workout routine can make people very worried about getting it wrong. szjphoto/Getty What optimisation and perfectionism share1. Constantly pursuing high standards

This means constantly working towards a goal and focusing on improvement. For example, it’s not enough to simply sleep or eat “well” – we need to strive for the “perfect” night’s sleep, or follow a precise and restrictive diet.

2. Being preoccupied with results

Focusing on certain end goals can become a source of worry and rumination, where you constantly go over the same problems in your head. People may be preoccupied about not meeting their goals perfectly and experience an intense fear of failure.

3. Constantly checking performance

Optimising encourages us to continually measure results to see if we’re improving. For example, by tracking sleep data every night, monitoring muscle gain or counting calories. But these behaviours can increase stress and could even be a sign of health anxiety or obsessive compulsive behaviours.

4. Procrastination and avoidance

People who have an intense fear of failure – of not doing something perfectly – often find starting a task overwhelming. This commonly leads to putting things off or avoiding them altogether. The pressure may be even more intense when we feel we have to “optimise” multiple areas of our lives at once.

5. Black and white thinking

This unhelpful habit is also known as “all or nothing” thinking. Everything is categorised into two opposing groups, with no middle ground. For example, your diet is either “healthy” (perfect and optimal) or “unhealthy” (imperfect and suboptimal). This type of thinking can intensify the fear of failure and avoidance that goes with it.

Finding balanceSome people will find an optimisation mindset helpful, and may not experience any negative effects.

But for others, focusing on optimising will likely carry risks of increased stress, anxiety and worse mental health. People with perfectionism, for example, may be more drawn to optimisation, which could then heighten this trait.

If you want to take a step back from optimising, you could try:

setting realistic goals by focusing on what’s measurable and achievable, rather than always striving for the best possible outcome

choosing goals that align with your personal values. For example, enjoying dinner out with friends and family, even if this means you won’t eat the “optimal” meal for health

taking breaks to reflect on what you’ve already achieved, rather than only focusing on the end point.

If you want to improve your health specifically, always consult with a qualified professional who will help tailor goals to your individual needs.

And if you’re really struggling with perfectionism, anxiety or poor mental health, it’s best to seek help. Your GP can help you identify the problem and recommend evidence-based treatments such as cognitive-behavioural therapy, which can help you reframe unhealthy thinking and behaviour.

Catherine Houlihan does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.