David Hicks's Blog, page 6

October 12, 2015

Short Story “Us and Mom at a Fancy-Schmancy Restaurant, If You Can Believe That” to Appear in Fall 2015 Crack the Spine

David’s story “Us and Mom at a Fancy-Schmancy Restaurant, If You Can Believe That” has been published in the online magazine Crack the Spine and will be featured in their “Best Of” print anthology in 2016/2017 . Read an excerpt below:

Read more at: ISSUU

The post Short Story “Us and Mom at a Fancy-Schmancy Restaurant, If You Can Believe That” to Appear in Fall 2015 Crack the Spine appeared first on David Hicks - Author.

Short Story “Jessi” to Appear in Fall 2015 Buck Off Magazine

David’s story “Jessi” has been published in the online magazine Buck Off . Read an excerpt below:

January 1996

It’s late at night when I leave. She is in her room, sound asleep. She

didn’t wake up when her mother hurled the coffee table at me and told me to get out, now.

She is not even two years old.

September 1996

She is in the back, buckled into her car seat. We smile at each other in

the rearview mirror. I have just picked her up from preschooL. I start the car, but when I try to back out, her mother’s red SUV pulls up behind me. Before I can think to lock the doors, her mother is leaning into my car, unbuckling her and tugging her out, aLL the while cursing me-for what, I’m not sure. For leaving the marriage, still? For telling her I no longer loved her? For hiring a lawyer to draw up a separation agreement?

She is crying now, reaching out for me.

June 1997

She is sitting on the floor, watching a Thomas the Tank Engine video and

snacking on Cheerios. We are in my new place, a tiny upstairs apartment in a cottage on the grounds of a much larger home. It’s where the horse groomer, or perhaps the gardener, used to live: one smaLL bedroom with a twin bed, walls covered with paneling.

A car pulls up, wheels over gravel. We hear a door slam, then someone

stomping up the stairs. It’s her mother, banging on the door, shouting out that I am an adulterer. We’ve been separated for a year and a half, and I just started dating someone, but the woman lives in Colorado so we only see each other once a month.

She looks up at me, her eyes wide. The banging and screaming continue. She opens her mouth and the wet Cheerios tumble out.

Read the full story here: Buck Off Magazine

The post Short Story “Jessi” to Appear in Fall 2015 Buck Off Magazine appeared first on David Hicks - Author.

July 5, 2015

In Omaggio a Mamma

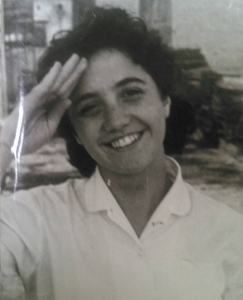

Yesterday I was driving with Cynthia, trying to figure out whether the temperature gauge on the car was called a thermometer or a thermostat, and I had this thought: if the English language is still tricky for me, and I have a PhD in it, how difficult would it have been for a 17-year-old Italian right off the boat?

Yesterday I was driving with Cynthia, trying to figure out whether the temperature gauge on the car was called a thermometer or a thermostat, and I had this thought: if the English language is still tricky for me, and I have a PhD in it, how difficult would it have been for a 17-year-old Italian right off the boat?

(Literally. Right off the boat.)

That 17-year-old was my mother. A year before that, as a 16-year-old cutie, Albinella Magliulo had met a handsome 22-year-old American named Richard Hicks in Naples, where he was stationed in the Navy, and they fell in love—apparently through mime, since they didn’t speak each other’s language—and were married at the little cathedral where she attended mass every Sunday. Eventually, his tour over, he came back to New York to find a job, and once he had done so, she voyaged over by herself on a ship, waited alone on the dock for her new husband to come get her (traffic jam on the West Side Highway, apparently), and then immediately assumed the role of American housewife.

At seventeen.

She had learned a little English before her voyage (from one of my father’s Navy buddies), learned more after arriving here (by attending night class, watching soap operas, and practicing with her new friends, sister-in-law, and neighbors) and gradually she would learn to communicate freely and fluently, eventually earning her American citizenship. But at first, it was certainly a struggle. She tells funny stories about herself (one day she found a bee in the bathroom, called my father at work and said something like “There’s an animal in here,” and my father called my grandfather, who burst into their home wielding a gun), and she says she was fine back then, it was no problem at all, but there must have been many long and lonely days, all alone by herself. Still, she fought through her linguistic hurdles as well as her emotional hardships (such as the loss of her daughter, my sister Sandra), to become the emotional core of our house, our domestic engineer.

I didn’t fully appreciate any of this when I was growing up. I mean, I knew I had the prettiest mother in the neighborhood, and I enjoyed being the recipient of her affection and care; but she was also the rule-maker, the one I had to rebel against as I grew older. But now, I think back to what it must have been like for her and am filled with appreciation. I mean, really. Could I have done what she did when I was that age? Highly unlikely. But there she was, having left her big, happy, well-to-do Italian family, barely scraping by with her working-class husband while being seen by some as a WOP who was using her marriage as a means to a better life—even though in reality she had taken a huge socio-economic step down. For love.

Fifty-plus years of it.

Fifty-plus years of it.

In my limited travels abroad, I have, on rare occasions, been to places where nobody spoke English. We are extremely fortunate people, we who speak this language, because we can count on there being somebody else–hotel clerks, taxi drivers, waiters–speaking it almost anywhere we go. Not so for any of the other six billion people occupying this planet. And certainly not so for a seventeen-year-old Italian immigrant in 1955.

I still don’t know how she did it. Classically educated in Italy, she was a very intelligent young woman, but she felt suddenly stupid, unable to carry on conversations, and as a result she muted her bright personality, often lapsing into silence in social situations. But she persevered. In fact once she had children, she refused to raise us as bilingual, and learned how to cook American food (hot dogs and baked beans, casseroles, turkey with brown gravy, boiled veggies with margarine, etc.)–all out of a determination to assimilate, to be a good citizen of her new country, to be a good wife to her American husband (who didn’t like fish, spicy foods, or even homemade ravioli!), to be a good mother to her American children.

When I was a boy, visiting Italy with my mother, our roles would suddenly reverse—she speaking happily and brightly in her native tongue, I faltering, struggling to put together coherent sentences, desperately translating in my head, trying to make sense of conversations around me. It was then that I would get a taste—just a taste—of what it must have been like for her in the first months of her new life in America. Years later, as a traveling adult—at a campsite in Patagonia, in a small village in rural France, in a shop in Prague, in a Gaelic-speaking church in Ireland—I would again experience such moments of alienation, listening to natives speaking in what was for me a linguistic cacophony, “full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.” But at the same time I was aware that this was, for me, just a moment; for my mother, that’s what it was like every minute of every day of her life.

After Cynthia and I chatted about this in the car, I called my mother to tell her how much I admired her, and to acknowledge how hard it must have been for her back then. She characteristically laughed it off, complaining that she still had an accent she should have lost by now and relaying some of her embarrassing English-language moments from those early days.

She has a tough time taking a compliment, my mother.

So after I told her I have always loved her accent, and that everyone who has ever spoken another language has had an accent, and that despite all her funny English mishaps she deserved a lot of credit for learning a new language completely on her own and adapting to a totally different culture, only to have her continue to deflect my compliments, I thought I might write it all down. If I did, I thought, she wouldn’t be able to deflect it; she wouldn’t be able to talk over me, joke about it, or change the topic.

So here it is, Mom: You’re amazing. Sei una donna straordinaria. You were just a girl, and look what you did. You learned a new language; you raised three children and endured the unendurable loss of a fourth; you supported your husband through his stressful jobs, his unjust firing, his risky purchase of a convenience mart (for years cooking huge pots of soup for him to sell there), his low wages as a security guard; you took on minimum-wage jobs when we needed extra money and have worked every year since, are in fact still working at age 77, never taking it easy, not for a single year of your life; and through all this you have loved us, loved your extended American family, loved our spouses, loved your grandchildren and step-grandchildren, loved us all more and more in fact as we have all aged, despite all the crap we have pulled.

If I were your friend or therapist, I would tell you to take it easy now, to fully retire, to spend more time in Italy, to let your children support you for a change. But I’m not, I’m just your son, and I know very well how stubborn you are, so all I will say is this:

Thank you.

Grazie mille.

Thank you for all your love, and thank you for being the kind of person I not only love back but also admire. Thank you for showing us all what grit and determination and optimism look like. And thank you for being so brave back then, back when you were a kid. For without you, without that bravery, where would we be?

Come siamo fortunati di avere una madre così coraggiosa e simpatica! Siamo molto grati, e ti vogliamo moltissimo

bene.

The post In Omaggio a Mamma appeared first on David Hicks - Author.

June 8, 2015

David Hicks: Co-Founder, Co-Director of the Mile-High MFA

David is now C0-Founder and Co-Director of the new Mile-High MFA in Creative Writing, Denver’s only MFA program.

He was interviewed by Eric Wyatt of “Words Matter” on the subject–you can listen to the podcast by clicking this link.

The post David Hicks: Co-Founder, Co-Director of the Mile-High MFA appeared first on David Hicks - Author.

An Interview by Margaret Cate

David was recently interviewed by the talented writer Margaret Cate.

As an English professor, you’ve been teaching literature for many years. What was the catalyst that prompted you to begin writing your own stories?

Well, I’d been teaching at the college level since I was twenty-two years old, and my PhD is in American literature, so for a long time I gave papers at academic conferences and published academic writing; but I always wanted to be a writer. The catalyst for my big switch was the same catalyst for all the big changes in my life: I got a divorce, quit my job, and moved to Colorado. Every single aspect of my life changed then, including what I pursued as intellectual labor. Also, for my first two years in the West, I lived with a writer, so I had a firsthand look at what the writing life was like, and I admired it. I began writing then–short stories. A few years later, in 2001, I was fortunate to find work at Regis University in Denver, a school that actually values creative work in addition to academic scholarship. (At most universities, creative work doesn’t count toward tenure or promotion.) So now I have the good fortune of working at a school that doesn’t just tolerate, but actually values, my creative work. That helps a lot. In other words, I don’t have to “sneak in” my creative writing; instead, it’s what I do, and my colleagues respect it.

How does teaching literature help to inform or improve your own writing process?

Oddly enough, I’ve never been asked that question. I think it both informs and improves my writing, both on a conscious and unconscious level. The act of reading–especially, I’d say, reading literary fiction–has no doubt embedded many stylistic, structural, and linguistic “templates” in my brain, and that has probably helped me to be a good writer. And teaching literature means I’m constantly reading and re-reading great works, so all those templates are constantly being reinforced and improved. And when I read, I quite consciously “read as a writer,” noting not just the what but the how of the work I’m reading. So I’m not only thinking thematically, as a professor does–or structurally, linguistically, generically, symbolically–but my writer self is thinking, Damn, my eyes just welled up–how did she do that? and I’ll go back through the passage and try to learn from it. So what this means is that I can re-read a canonical work like Moby-Dick (which I just did, a few weeks ago) and mark passages I want to be sure to go over in class, because they speak to a particular theme or represent a particular stylistic move I want the students to learn, and at the same time know that it’s good for me as a writer because I’m (unconsciously) hard-wiring some of that gorgeous style in my brain and I might (consciously) mimic something of that style, or that theme, in my own work-in-progress.

You can read the entire interview here.

The post An Interview by Margaret Cate appeared first on David Hicks - Author.

You Say Goodbye When I Say Hello– a new essay from David Hicks

David has published a new essay in the eclectic on-line magazine, Queen Mob’s Tea House. It’s about the importance of saying hello to one another. Really. It’s important.

Yesterday I was on the lovely campus of the university where I work, walking down the brick path alongside the big lawn. It was a sunny morning, and the many trees (our campus is an arboretum) are in bloom. There was only one other person on the path—a student, walking towards me—so I caught his eye and said, “Good morning.”

What happened next was fairly typical, in that what happened next was . . . absolutely nothing. He looked away, and we continued walking in opposite directions.

Granted, I was in a great mood (I love where I work, the sun was out . . . did I mention the trees are in bloom?), and the student, given that the semester is winding down, may have been stressed or preoccupied. But he certainly didn’t seem stressed. He was sauntering toward one of the classroom buildings, probably to grab a coffee or a bite to eat before the next class period started. He wasn’t wearing earbuds, and I hadn’t mumbled. He had certainly heard me. But for whatever reason, he didn’t see fit to return a “good morning” to a professor at the small liberal-arts school he attended.

Considered in the abstract, his reaction is perfectly acceptable. He had every right not to return my greeting. Just because I say hi to someone doesn’t mean they have to say hi back. And I was clearly in violation of the Personal Space Rule: Don’t say hi to someone you don’t know. But, since to me this is trumped by the Shared Space Rule (We’re all fellow occupants of the same place and engaged in a shared enterprise), and since I’ve seen him before and he’s seen me, and since this kind of (non)interaction has happened, oh, about four hundred times this semester, it’s left me wondering: what’s a guy got to do to get a hello around here?

You can read the entire essay here!

The post You Say Goodbye When I Say Hello– a new essay from David Hicks appeared first on David Hicks - Author.

May 19, 2015

Sports Fanaticism: or, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind

Yesterday, the Colorado Rockies lost their eleventh game in a row and are cemented in last place.

It’s May. We’ve got 130 games to go.

Last spring, I was stunned when Vegas oddsmakers listed the 2014 Rockies’ over/under (for total number of wins) as 76 games. 76 games! What a joke, thought I. They will easily win 76 games; they have the best offensive lineup in baseball, with promising young pitchers and a solid bullpen. I predicted their win total to be about 88 games and felt they had a good chance of making the Wild Card. I have never bet on a sporting event (except for the NCAA basketball pool, which hardly seems to count), but here was my chance. If I put a thousand dollars down on the Colorado Rockies winning over 76 games, I would win $1900.

I never placed the bet.

Total wins for the Colorado Rockies, 2014: 66.

This year’s over-under was 71 ½ games. And again, I had the same thought: What? They’re absolutely going to win 72 games. Those people in Vegas clearly don’t know what they’re doing.

Which brings us to today’s topic: How my sports fanaticism turns me into an idiotic optimist.

What I tell my friends: “Yeah, they’re going to suck again. Too bad the owners are so cheap they didn’t get us an ace.”

What I secretly think: We are going to win it all. This city is going to go nuts.

What I tell my friends: “We’ve got the number 5 starter for the Phillies last year as our Opening Day pitcher!? The season is already doomed.”

What I secretly think: Kendrick’s going to flourish. Gray and Butler are going to compete for Rookie of the Year. De La Rosa’s going to win the Cy Young. That Matzek kid looks good. Ottavino is freakin’ unhittable.

Whence this lunacy?

Here’s how it works: We have four position players (Tulowitski, Gonzalez, Arenado, and Morneau) I would take over almost anyone else at those positions. We have great late-inning relievers. So our starting pitching just needs to be competent. If everyone stays healthy, we have a shot at the playoffs.

You may say, Uh, except for one thing, Dave: that’s never happened. No team has ever won with mediocre starting pitching. To which I would respond, “How wrong you are, my friend.”

It’s the Curse of 2007.

In 2007, the Rockies finished the season winning fourteen of their last fifteen games, won a thrilling fourteen-inning play-in game against San Diego (I recently watched a video of the winning run: Matt Holliday still hasn’t touched home plate, and the catcher still hasn’t tagged him), and then swept the Phillies and Diamondbacks to make the World Series—in other words, they won 20 of their last 21 games. They then had to endure a ridiculous eight-day delay (the longest wait in baseball history) before the World Series began, during which it snowed in Denver, they were unable to practice, and they completely cooled off. By the time the players got their swings back, the Red Sox had blown them out in what must be considered the Most Boring Series Ever—except for all those long-suffering Sox fans, of course.

A thrilling season, in other words, but for the WS loss. So why, you ask, was that a curse?

Because miracles don’t happen twice.

Because 2007 has imbedded itself in the minds of Rockies’ management. They learned a terrible lesson: that they can actually win with homegrown talent, great hitting, and mediocre pitching.

They have since followed that formula every year since, with the same results. Right now they’re 11-19 and solidly in last place—in what has become a very strong division. And they don’t have an ace.

In other words, we’re screwed again–and at a time when this sports-crazed town desperately needs the Rockies to be competitive. The Broncos blew it again, the Nuggets have been awful, the Avs are mediocre. We turn to the Rockies for salvation. We need them to be good this year. And yet they are already not.

I grew up as a Mets fan, so (except for that brief and magical interlude in 1986) I have spent most of my life ardently devoted to losers. I’m beginning to think that I’m a fan of these teams BECAUSE they lose. In other words, there must be something about me that wants and needs to cling to hope when there is none.

Believe me, I’m laughing at myself. What is wrong with me? But really, the Rockies would have been so good last year were it not for all their injuries! I mean, whoever heard of five players breaking their hands, and every starting pitcher on the Disabled List? What rotten luck!

I’m so pathetic.

But still: the Rockies really have had rotten luck. It’s as if they used it all up in 2007. And for a team to succeed, it has to have talent, yes, but also extraordinary luck: it must somehow keep everyone healthy, and it has to have timely hitting that means they win more one-run games than they lose—and often that’s just a matter of a line drive hit slightly to the left of the center fielder instead of right at him, or a hard ground ball going through the hole instead of within range of the second baseman, or a looping hit down the line that kicks up chalk instead of landing just foul. It also means the 3-2 slider nipping the corner, the right fielder not slightly misjudging that gapper in the ninth . . .

In other words, the cliché is true: baseball is a game of inches.

Actually, all sports are games of inches.

Think about it: If Rahim Moore had properly defended Joe Flacco’s pass at the end of the 2013 Ravens-Broncos playoff game, the Broncos would probably have gone on to win the Super Bowl and nobody would be talking about Peyton Manning’s inability to win the big one. If Chris Wondolowski would have kicked the ball a little more gently at the end of the U.S.-Belgium game, the U.S. may have advanced to the World Cup quarterfinals. If Tony Parker had slapped the ball out of Ray Allen’s hand before Allen made his game-tying three-pointer at the end of Game 6 in the 2013 NBA finals (watch the replay—Parker’s hand is an inch away, and I still have no idea why he didn’t try to slap it away) we’d be talking about a Spurs dynasty and NBA teams would be focused on building great teams, not luring superstars. If Russell Wilson had thrown the ball slightly to his receiver’s left (or Macolm Butler had hesitated a millisecond before dashing toward the ball), there would have been no interception, and we’d be talking about a potential Seahawks dynasty.

So why bother? I mean, if so many key incidents in sports are ruled by chance, and 99% of the time one’s devotion to a sports team results in heartbreaking frustration, then why bother?

This is the unspoken question my wife asks when my mood turns sour after another Rockies loss. What on earth is the big deal? It’s so beyond her (or any intelligent person’s) understanding that she typically doesn’t believe me; something else besides a stupid baseball game must be the cause of my foul mood. Was it something she did? Something work-related? “No,” I said to her yesterday, “really, it’s because the Rockies lost again, and they could have won, if only . . .”

I didn’t bother trying to explain the many reasons why the Rockies lost: the manager bringing in the righthander when the lefty was pitching great; the baserunning mistake that would have provided the tying run, the rightfielder overthrowing the cut-off man, which allowed the runner behind the play to advance and later score on the infield hit. Instead, I apologized. “I’m afraid this is who you’re married to,” I said. “A guy whose mood can completely change based on the outcome of a sporting event.”

If you’re a sports fan, and you’re reading this, you’re nodding your head. But here’s the question: Why? Why do otherwise somewhat-intelligent people completely fall in love with a group of athletes chasing a ball around in a completely meaningless enterprise? Or to paraphrase Jerry Seinfeld, since we remain loyal to a team even after they trade away our favorite players, why are we so devoted to the color of a uniform? How is it that we’ve become fans of laundry?

It must be that it satisfies, or feeds, some elemental need in us to perpetually hope for something. Because for the majority of fans (Cubs Nation, take note), that payoff—that long-awaited thrill of victory—either never happens, or it happens once and that’s it. (After the Mets won the World Series in 1986, I was convinced that with their pitching staff they would be even better in 1987—I actually told my brother, “I don’t see how they can lose one game!”—but that dynasty never materialized.) And I suspect that, as with the lottery or religion, hope grows in proportion to our own level of misery. Suffering—whether due to a bad economy or trouble in our personal lives, whether in sports or religion—increases fanaticism. I know that the happier I’ve become in my own life, the less clingy I am to my sports teams. But it’s still there. And my loyalties are strong—though not inflexible. When I moved from New York to Colorado, I was convinced I would remain a Mets fan (it was in my blood, I felt), but it so happens that the year I moved was the year when the Mets completely revamped their roster, so that not a single position player remained from the team I had just rooted for; and in the meantime, the Rockies, in the throes of the Blake Street Bombers era and still new enough that they were selling out every game, were just a hell of a lot of fun. So I fell in love with one team and out of love with the other, in the same way a fourteen-year-old might fall out of love with one person when meeting a new, more attractive person. So while I do hope the Mets do well, every year, in the same way I hope my ex-girlfriend finds happiness with another man, I no longer feel any conflict when they come to town. (Though I do feel a certain tug on my heartstrings when I see the blue-and-orange uniforms). And the same goes for the other teams I’ve abandoned (the Rams and Knicks) for the sake of my new hometown teams (Broncos and Nuggets).

Which brings up another reason why we do this: rooting for a sports team strengthens one’s attachment to one’s home. And an attachment to home, a sense of belonging, is one of our most basic needs.

Those who smugly denigrate such ethnocentric or hormone-driven devotion to sports (and this includes most of my colleagues in academia) fail to recognize their own irrational addictions—to a musical group, an author, a film director, a philosopher—somebody or something whose new production or venture fills them with anticipation, whose failures clutch at their hearts, and about whom they have no semblance of objectivity. Sports is simply more public, more visceral, more physical, more boorish than the other addictions.

And ancestral as well. Or at least familial, even nationalistic. Many of us inherit our fanaticism from our parents the way we inherit our religions: my nephew is a Yankees fan because his father is a Yankees fan, in almost precisely the same way that he’s Catholic because his mother is Catholic. Both affinities are illogical—ideally, people should choose their own system of faith as well as their sports teams, right—and as well as unjustified. (Why think their team is the Greatest Team of All, or that their God is the One True God, if it’s merely an accident that they were born into that belief system?) And yet there you have it. It’s true, and it’s fun (or at least the sports affiliation is–I can’t speak for the religious), and when their teams lose, they drop to their knees and weep, and when the host country of a World Cup tournament loses 7-1 the entire nation is humiliated. And when their teams win it all, they celebrate in a bigger, more exultant way than when they marry, or win an election, or give birth, or are promoted. They celebrate as if their very lives have been saved, as if their existence on this planet has been granted meaning. It means that they have, for once, fastened their heart to something triumphant, that by living in this place and suffering through all those losses they have earned this victory, they deserve it, and it’s all been worth it, and they can die in peace.

And if they don’t experience such triumph (again, I’m talking to you, Cubs fans), they brag about how much they have suffered, how loyal they are. Oh sure, they say, it’s easy to be a Yankees fan. To be a Cubs fan? That takes integrity. True loyalty. What has not killed us has made us stronger. (And more obnoxious.)

At bottom, it’s all just a diversion—sports, that is—just as, perhaps, watching the strongest fighter battling a mastodon thousands of years ago was. But such battles, such sports, were more meaningful back then: if the human won, that meant everyone got to eat; when warriors kicked a severed head of the enemy around the battlefield in celebration of the kill (the origin of soccer), it meant breaking the opponents’ spirit and helping to bring about victory in war. So maybe we’re carrying around that ancestral meaning now, in our genes, even though the diversion has become meaningless in the grand scheme of things.

Sports, like religion, is the opiate of the masses, a raison d’etre for the poor and disenfranchised (except for the fact that the poor and disenfranchised can no longer afford tickets), just as a rock band or hip-hop artist could be to a sad and lonely teenager. One’s devotion to it may provide a modicum of meaning to a life that has little meaning. Or for me, and for millions of other adults who love sports, it could be a way of remembering the beautiful connectivity we felt when we played, the “team-ness” (which I wrote about here) we still crave. We remember, in the cells of our body, what it felt to be outdoors, or in a gym, working in unison with our peers to achieve a goal—an enterprise in which (as Philip Larkin said of churches) ordinary events are “robed as destinies.” We know they are meaningless, and yet at the same time we assign great meaning to them, for we crave, enjoy, and need this connectivity and purpose, especially when our devotion also links us with a community of likeminded worshippers–which is, beneath it all, something that religion provides as well.

Forgive me, then, as I predict great success for the Rockies this year, in spite of their slow start, for I am doing so with the full comprehension of its silliness even while I earnestly assign great importance to it. (As F. Scott Fitzgerald said, “the test of a first rate intelligence is the ability to hold opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function.”) You should look kindly upon me, pathetic as I am, for it means that I retain and am expressing hope and faith in what is fast becoming an utterly hopeless and faithless world.

The post Sports Fanaticism: or, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind appeared first on David Hicks - Author.