David Hicks's Blog, page 2

May 10, 2024

“A Beautiful Collaboration”: Writing and Illustrating a Children’s Book Together

In most cases, a children’s book is written by the author, the author is fortunate enough to find a publisher, and then the publisher assigns an illustrator to the project. But in the case of THE MAGIC TICKET , the author, David Hicks, first wrote a deeply personal, autobiographical story, then approached his talented friend Kateri Kramer to see if she was interested in illustrating it. The two then collaborated on the book, shaping and revising it together based on their shared ideas, and then approached the publisher together with the finished product. And it worked! Fulcrum Books is publishing it in July of this year.

Here the author and illustrator talk about their unusually collaborative process:

(Kateri:) You’ve primarily written adult fiction and taught adult creative writing classes. What was the catalyst for The Magic Ticket and how was the process for writing a picture book different?

(Kateri:) You’ve primarily written adult fiction and taught adult creative writing classes. What was the catalyst for The Magic Ticket and how was the process for writing a picture book different?

(David:) Same kind of catalyst, very different process. :-) My stories and novels, while fiction, are all based on something that happened to me, an event or encounter that changed me in some way, small or big. That’s no different for this children’s book, which is based on the biggest thing that happened to me, which is that when I was a boy, my sister died suddenly, in the middle of the night, and my family, along with my view of myself, my very being, was forever changed. But the difference in this event, and thus in the process of writing it, is that it was too big for me to get a handle on it. That’s why I’d been avoiding it. In order to write it, therefore, I had to make it really simple. So I reverted to a formula, a lesson I teach my students about story structure: Once upon a time . . . . Then, one day . . . .

(David:) Same kind of catalyst, very different process. :-) My stories and novels, while fiction, are all based on something that happened to me, an event or encounter that changed me in some way, small or big. That’s no different for this children’s book, which is based on the biggest thing that happened to me, which is that when I was a boy, my sister died suddenly, in the middle of the night, and my family, along with my view of myself, my very being, was forever changed. But the difference in this event, and thus in the process of writing it, is that it was too big for me to get a handle on it. That’s why I’d been avoiding it. In order to write it, therefore, I had to make it really simple. So I reverted to a formula, a lesson I teach my students about story structure: Once upon a time . . . . Then, one day . . . .

So I decided to use this structure to write about the most formative event of my childhood, as a starting point: Once upon a time there was a boy who lived in a very happy household with a loving mom, a kindhearted dad, a big brother he admired, and a little sister he adored. Then, one dark night, his sister died. And there it was, my story, in its simplest form. I then set about filling it out–it could be a memoir or novel–I figured. Then again, I thought, I could keep it simple, and it might have more power that way. So I tried it as a children’s story, even though I didn’t know the first thing about writing a children’s story.

“Then again, I thought, I could keep it simple, and it might have more power that way.”

How about you? You’re a writer and a creator, but how did you become an illustrator? How is illustrating a children’s book different from the kind of drawing/illustrating you’ve done in the past?

I’ve been doing visual art since I was very little because my dad was a painter. He used to give me and a few friends drawing lessons on Saturdays so I think being an illustrator felt really natural. It wasn’t until 2020 when I took a class with The Goodship Illustration when I realized that being an illustrator was something I could do as a job (or a side-job). In the past I’ve done a lot of brand identity illustration (everything from logos, to brand iconography and assets for websites), but a children’s book is a very different ballgame. While both types of illustration have to have a cohesive feel and belong together, the consistency required in a picture book is at a different level. This was the first time I had to make sure that the proportions of the characters, the decorations in the rooms, and the coloring of different objects like the wagon or the cat were the same on page one as they are on page 30. There’s a lot of organization and checking then rechecking, then rechecking again that goes into picture book illustration.

I’ve been doing visual art since I was very little because my dad was a painter. He used to give me and a few friends drawing lessons on Saturdays so I think being an illustrator felt really natural. It wasn’t until 2020 when I took a class with The Goodship Illustration when I realized that being an illustrator was something I could do as a job (or a side-job). In the past I’ve done a lot of brand identity illustration (everything from logos, to brand iconography and assets for websites), but a children’s book is a very different ballgame. While both types of illustration have to have a cohesive feel and belong together, the consistency required in a picture book is at a different level. This was the first time I had to make sure that the proportions of the characters, the decorations in the rooms, and the coloring of different objects like the wagon or the cat were the same on page one as they are on page 30. There’s a lot of organization and checking then rechecking, then rechecking again that goes into picture book illustration.

“I’ve done a lot of brand identity illustration . . . but a children’s book is a very different ballgame.”

Speaking of process, how did you go about writing The Magic Ticket and what was your revision system like? Was it harder than a full-length adult book because there were such strict boundaries around word count?

My first draft was, I think, around 900 words, but it wasn’t too difficult to pare it down to the 700-word expectation for picture books–in fact, I rather enjoyed the process, whereas in novel-writing deleting words and scenes is arduous and painful. The big difference was in my focus on diction and sound, as opposed to scene or character development–it felt more like poetry than narrative. When I revised my current novel (from a whopping 170,000 words to a closer-to-normal 98,000), I hacked away at scenes and secondary characters, based on what was and what was not essential to the story. But with The Magic Ticket, the story was already at its essential level, already bare-bones, so I acted more like a poet, focusing on sound and rhythm on a word-by-word basis. Even now, as you and I are making final revisions to the galleys, I’m deleting words based on sound and rhythm–and on something I’ve never had to consider before: the look of the page. Once I saw the galleys with your beautiful illustrations, I could also see that some pages were too crowded with my text, and that some of your illustrations rendered some of my text unnecessary. For example, do we need the words, “His mother was very, very sad” if your illustration (of the boy’s mother lying on the couch, despondent) conveys that sadness? These are the kinds of revisions I really enjoy, not only because they are brand-new to me, but also because of the collaborative aspect . Writing is typically a very lonely occupation, so it’s been great fun to co-author this book with someone who is so creative in a way that I’m decidedly not. (I mean, even my stick figures are embarrassing.)

My first draft was, I think, around 900 words, but it wasn’t too difficult to pare it down to the 700-word expectation for picture books–in fact, I rather enjoyed the process, whereas in novel-writing deleting words and scenes is arduous and painful. The big difference was in my focus on diction and sound, as opposed to scene or character development–it felt more like poetry than narrative. When I revised my current novel (from a whopping 170,000 words to a closer-to-normal 98,000), I hacked away at scenes and secondary characters, based on what was and what was not essential to the story. But with The Magic Ticket, the story was already at its essential level, already bare-bones, so I acted more like a poet, focusing on sound and rhythm on a word-by-word basis. Even now, as you and I are making final revisions to the galleys, I’m deleting words based on sound and rhythm–and on something I’ve never had to consider before: the look of the page. Once I saw the galleys with your beautiful illustrations, I could also see that some pages were too crowded with my text, and that some of your illustrations rendered some of my text unnecessary. For example, do we need the words, “His mother was very, very sad” if your illustration (of the boy’s mother lying on the couch, despondent) conveys that sadness? These are the kinds of revisions I really enjoy, not only because they are brand-new to me, but also because of the collaborative aspect . Writing is typically a very lonely occupation, so it’s been great fun to co-author this book with someone who is so creative in a way that I’m decidedly not. (I mean, even my stick figures are embarrassing.)

“[Revising a children’s book] felt more like poetry than narrative.”

How about you? What’s it like to bring to life someone else’s words, someone else’s story, while also “making it your own” and adding your own ideas/images? And what’s it like to put your heart into an illustration only to have the author request a modification of that illustration?

It was a lot more challenging than I thought it would be (probably part of the reason I procrastinated…overthinking it!). I will say that my experience might have been a-typical because I didn’t have traditional art direction (could have made it easier or more challenging) and you and I have known each other for a while. If I didn’t know the author I might not have been so worried that they wouldn’t like it. However, I think the fact that we do know each other, and have worked together, made me really think and rethink and rethink again, which was good. In the future, I know that I will need to take more time for sketches and exploration, which anxiety/full-time-job/artist-block/first-time-illustrator jitters didn’t afford me this time around.

It was a lot more challenging than I thought it would be (probably part of the reason I procrastinated…overthinking it!). I will say that my experience might have been a-typical because I didn’t have traditional art direction (could have made it easier or more challenging) and you and I have known each other for a while. If I didn’t know the author I might not have been so worried that they wouldn’t like it. However, I think the fact that we do know each other, and have worked together, made me really think and rethink and rethink again, which was good. In the future, I know that I will need to take more time for sketches and exploration, which anxiety/full-time-job/artist-block/first-time-illustrator jitters didn’t afford me this time around.

Because I didn’t have that traditional art direction, I relied on you very heavily for input about how illustrations looked, consistency, variation in perspective, and color. I’m immensely grateful that you were so thoughtful and attentive to it. Not to mention this is YOUR story and I very much wanted to represent it in a way that felt accurate.

We kept revising both the text and the illustrations through to the end of the process. Are you happy with the way the text turned out? How does marketing a children’s book differ from an adult book?

Yes, I’m delighted with how it turned out! I’m always happy when an editor forces me to cut a certain number of words; it compels me to adopt an economy of language that’s always good for writing (in any genre). In this case, because of how the layout changed the book’s pagination, we realized we needed to trim a couple of pages from the end of the book, which forced us to trim both words and images from the final four pages, and I think it made the book better. I certainly loved how your new illustrations for those final pages turned out. So of course that (the limited number of pages and words required of a picture book) is nothing I would even have to think about with a literary novel; but I enjoyed the challenge it presented us with.

Yes, I’m delighted with how it turned out! I’m always happy when an editor forces me to cut a certain number of words; it compels me to adopt an economy of language that’s always good for writing (in any genre). In this case, because of how the layout changed the book’s pagination, we realized we needed to trim a couple of pages from the end of the book, which forced us to trim both words and images from the final four pages, and I think it made the book better. I certainly loved how your new illustrations for those final pages turned out. So of course that (the limited number of pages and words required of a picture book) is nothing I would even have to think about with a literary novel; but I enjoyed the challenge it presented us with.

As for marketing, you would know better than I, but for me it’s been markedly different. I’m not only presenting myself in a different way (that is, as a children’s author, a warmer/friendlier version of my serious-novelist persona); but I’m working with a different audience. With my novels, I pitched readings at bookstores. Simple. With The Magic Ticket, I’m talking with schools, libraries, grief-counseling centers (because of the Magic Ticket’s subject matter), and yes, bookstores too–but for obvious reasons giving a storytime reading to children is very different from a literary reading to adults. I’m marketing myself more than the book, in a way, and when I pitch the book, I’m pretty much giving the whole story away (it’s only 700 words, after all), opposed to just a glimpse of it (for a 100,000-word novel). At the same time, just as with my last book tour for my novel, it’s all about connections. It’s all about believing in the book.

“[I]t’s all about connections. It’s all about believing in the book.”

For you, what’s it been like to wear two different hats, one business-y (marketing) and one creative (illustrator). And what are your hopes for this book?

It’s both a challenge and a super cool opportunity. I think it gives me the opportunity to think about marketing needs differently because if we want something special for the book like a promo sticker, I can just illustrate it. On the other hand, it’s challenging because I’m not just living in the realm of the illustrator, I’m also balancing all the marketing needs. My biggest hope for this book is that it opens up conversations about loss and grief for both children and parents/counselors/librarians/guardians. Children today are facing so much more grief, whether it’s loss of a family member, or dealing with the consequences of Covid, or dealing with the fear/grief/uncertainty of our world (whether from hearing it themselves, or feeling the uncertainty from guardians). I think that talking about all of that at an early age means that children will feel more able to continue those conversations, and feel their feelings as adults. Or at least that’s my hope.

It’s both a challenge and a super cool opportunity. I think it gives me the opportunity to think about marketing needs differently because if we want something special for the book like a promo sticker, I can just illustrate it. On the other hand, it’s challenging because I’m not just living in the realm of the illustrator, I’m also balancing all the marketing needs. My biggest hope for this book is that it opens up conversations about loss and grief for both children and parents/counselors/librarians/guardians. Children today are facing so much more grief, whether it’s loss of a family member, or dealing with the consequences of Covid, or dealing with the fear/grief/uncertainty of our world (whether from hearing it themselves, or feeling the uncertainty from guardians). I think that talking about all of that at an early age means that children will feel more able to continue those conversations, and feel their feelings as adults. Or at least that’s my hope.

“My biggest hope for this book is that it opens up conversations about loss and grief for both children and parents . . .”

“A Beautiful Collaboration”: Writing and Illustrating a Children’s Book

In most cases, a children’s book is written by the author, the author is fortunate enough to find a publisher, and then the publisher assigns an illustrator to the project. But in the case of THE MAGIC TICKET , the author, David Hicks, first wrote a deeply personal, autobiographical story, then approached his talented friend Kateri Kramer to see if she was interested in illustrating it. The two then collaborated on the book, shaping and revising it together based on their shared ideas, and then approached the publisher together with the finished product. And it worked! Fulcrum Books is publishing it in July of this year.

Here the author and illustrator talk about their unusually collaborative process:

(Kateri:) You’ve primarily written adult fiction and taught adult creative writing classes. What was the catalyst for The Magic Ticket and how was the process for writing a picture book different?

(Kateri:) You’ve primarily written adult fiction and taught adult creative writing classes. What was the catalyst for The Magic Ticket and how was the process for writing a picture book different?

(David:) Same kind of catalyst, very different process. :-) My stories and novels, while fiction, are all based on something that happened to me, an event or encounter that changed me in some way, small or big. That’s no different for this children’s book, which is based on the biggest thing that happened to me, which is that when I was a boy, my sister died suddenly, in the middle of the night, and my family, along with my view of myself, my very being, was forever changed. But the difference in this event, and thus in the process of writing it, is that it was too big for me to get a handle on it. That’s why I’d been avoiding it. In order to write it, therefore, I had to make it really simple. So I reverted to a formula, a lesson I teach my students about story structure: Once upon a time . . . . Then, one day . . . .

(David:) Same kind of catalyst, very different process. :-) My stories and novels, while fiction, are all based on something that happened to me, an event or encounter that changed me in some way, small or big. That’s no different for this children’s book, which is based on the biggest thing that happened to me, which is that when I was a boy, my sister died suddenly, in the middle of the night, and my family, along with my view of myself, my very being, was forever changed. But the difference in this event, and thus in the process of writing it, is that it was too big for me to get a handle on it. That’s why I’d been avoiding it. In order to write it, therefore, I had to make it really simple. So I reverted to a formula, a lesson I teach my students about story structure: Once upon a time . . . . Then, one day . . . .

So I decided to use this structure to write about the most formative event of my childhood, as a starting point: Once upon a time there was a boy who lived in a very happy household with a loving mom, a kindhearted dad, a big brother he admired, and a little sister he adored. Then, one dark night, his sister died. And there it was, my story, in its simplest form. I then set about filling it out–it could be a memoir or novel–I figured. Then again, I thought, I could keep it simple, and it might have more power that way. So I tried it as a children’s story, even though I didn’t know the first thing about writing a children’s story.

“Then again, I thought, I could keep it simple, and it might have more power that way.”

How about you? You’re a writer and a creator, but how did you become an illustrator? How is illustrating a children’s book different from the kind of drawing/illustrating you’ve done in the past?

I’ve been doing visual art since I was very little because my dad was a painter. He used to give me and a few friends drawing lessons on Saturdays so I think being an illustrator felt really natural. It wasn’t until 2020 when I took a class with The Goodship Illustration when I realized that being an illustrator was something I could do as a job (or a side-job). In the past I’ve done a lot of brand identity illustration (everything from logos, to brand iconography and assets for websites), but a children’s book is a very different ballgame. While both types of illustration have to have a cohesive feel and belong together, the consistency required in a picture book is at a different level. This was the first time I had to make sure that the proportions of the characters, the decorations in the rooms, and the coloring of different objects like the wagon or the cat were the same on page one as they are on page 30. There’s a lot of organization and checking then rechecking, then rechecking again that goes into picture book illustration.

I’ve been doing visual art since I was very little because my dad was a painter. He used to give me and a few friends drawing lessons on Saturdays so I think being an illustrator felt really natural. It wasn’t until 2020 when I took a class with The Goodship Illustration when I realized that being an illustrator was something I could do as a job (or a side-job). In the past I’ve done a lot of brand identity illustration (everything from logos, to brand iconography and assets for websites), but a children’s book is a very different ballgame. While both types of illustration have to have a cohesive feel and belong together, the consistency required in a picture book is at a different level. This was the first time I had to make sure that the proportions of the characters, the decorations in the rooms, and the coloring of different objects like the wagon or the cat were the same on page one as they are on page 30. There’s a lot of organization and checking then rechecking, then rechecking again that goes into picture book illustration.

“I’ve done a lot of brand identity illustration . . . but a children’s book is a very different ballgame.”

Speaking of process, how did you go about writing The Magic Ticket and what was your revision system like? Was it harder than a full-length adult book because there were such strict boundaries around word count?

My first draft was, I think, around 900 words, but it wasn’t too difficult to pare it down to the 700-word expectation for picture books–in fact, I rather enjoyed the process, whereas in novel-writing deleting words and scenes is arduous and painful. The big difference was in my focus on diction and sound, as opposed to scene or character development–it felt more like poetry than narrative. When I revised my current novel (from a whopping 170,000 words to a closer-to-normal 98,000), I hacked away at scenes and secondary characters, based on what was and what was not essential to the story. But with The Magic Ticket, the story was already at its essential level, already bare-bones, so I acted more like a poet, focusing on sound and rhythm on a word-by-word basis. Even now, as you and I are making final revisions to the galleys, I’m deleting words based on sound and rhythm–and on something I’ve never had to consider before: the look of the page. Once I saw the galleys with your beautiful illustrations, I could also see that some pages were too crowded with my text, and that some of your illustrations rendered some of my text unnecessary. For example, do we need the words, “His mother was very, very sad” if your illustration (of the boy’s mother lying on the couch, despondent) conveys that sadness? These are the kinds of revisions I really enjoy, not only because they are brand-new to me, but also because of the collaborative aspect . Writing is typically a very lonely occupation, so it’s been great fun to co-author this book with someone who is so creative in a way that I’m decidedly not. (I mean, even my stick figures are embarrassing.)

My first draft was, I think, around 900 words, but it wasn’t too difficult to pare it down to the 700-word expectation for picture books–in fact, I rather enjoyed the process, whereas in novel-writing deleting words and scenes is arduous and painful. The big difference was in my focus on diction and sound, as opposed to scene or character development–it felt more like poetry than narrative. When I revised my current novel (from a whopping 170,000 words to a closer-to-normal 98,000), I hacked away at scenes and secondary characters, based on what was and what was not essential to the story. But with The Magic Ticket, the story was already at its essential level, already bare-bones, so I acted more like a poet, focusing on sound and rhythm on a word-by-word basis. Even now, as you and I are making final revisions to the galleys, I’m deleting words based on sound and rhythm–and on something I’ve never had to consider before: the look of the page. Once I saw the galleys with your beautiful illustrations, I could also see that some pages were too crowded with my text, and that some of your illustrations rendered some of my text unnecessary. For example, do we need the words, “His mother was very, very sad” if your illustration (of the boy’s mother lying on the couch, despondent) conveys that sadness? These are the kinds of revisions I really enjoy, not only because they are brand-new to me, but also because of the collaborative aspect . Writing is typically a very lonely occupation, so it’s been great fun to co-author this book with someone who is so creative in a way that I’m decidedly not. (I mean, even my stick figures are embarrassing.)

“[Revising a children’s book] felt more like poetry than narrative.”

How about you? What’s it like to bring to life someone else’s words, someone else’s story, while also “making it your own” and adding your own ideas/images? And what’s it like to put your heart into an illustration only to have the author request a modification of that illustration?

It was a lot more challenging than I thought it would be (probably part of the reason I procrastinated…overthinking it!). I will say that my experience might have been a-typical because I didn’t have traditional art direction (could have made it easier or more challenging) and you and I have known each other for a while. If I didn’t know the author I might not have been so worried that they wouldn’t like it. However, I think the fact that we do know each other, and have worked together, made me really think and rethink and rethink again, which was good. In the future, I know that I will need to take more time for sketches and exploration, which anxiety/full-time-job/artist-block/first-time-illustrator jitters didn’t afford me this time around.

It was a lot more challenging than I thought it would be (probably part of the reason I procrastinated…overthinking it!). I will say that my experience might have been a-typical because I didn’t have traditional art direction (could have made it easier or more challenging) and you and I have known each other for a while. If I didn’t know the author I might not have been so worried that they wouldn’t like it. However, I think the fact that we do know each other, and have worked together, made me really think and rethink and rethink again, which was good. In the future, I know that I will need to take more time for sketches and exploration, which anxiety/full-time-job/artist-block/first-time-illustrator jitters didn’t afford me this time around.

Because I didn’t have that traditional art direction, I relied on you very heavily for input about how illustrations looked, consistency, variation in perspective, and color. I’m immensely grateful that you were so thoughtful and attentive to it. Not to mention this is YOUR story and I very much wanted to represent it in a way that felt accurate.

We kept revising both the text and the illustrations through to the end of the process. Are you happy with the way the text turned out? How does marketing a children’s book differ from an adult book?

Yes, I’m delighted with how it turned out! I’m always happy when an editor forces me to cut a certain number of words; it compels me to adopt an economy of language that’s always good for writing (in any genre). In this case, because of how the layout changed the book’s pagination, we realized we needed to trim a couple of pages from the end of the book, which forced us to trim both words and images from the final four pages, and I think it made the book better. I certainly loved how your new illustrations for those final pages turned out. So of course that (the limited number of pages and words required of a picture book) is nothing I would even have to think about with a literary novel; but I enjoyed the challenge it presented us with.

Yes, I’m delighted with how it turned out! I’m always happy when an editor forces me to cut a certain number of words; it compels me to adopt an economy of language that’s always good for writing (in any genre). In this case, because of how the layout changed the book’s pagination, we realized we needed to trim a couple of pages from the end of the book, which forced us to trim both words and images from the final four pages, and I think it made the book better. I certainly loved how your new illustrations for those final pages turned out. So of course that (the limited number of pages and words required of a picture book) is nothing I would even have to think about with a literary novel; but I enjoyed the challenge it presented us with.

As for marketing, you would know better than I, but for me it’s been markedly different. I’m not only presenting myself in a different way (that is, as a children’s author, a warmer/friendlier version of my serious-novelist persona); but I’m working with a different audience. With my novels, I pitched readings at bookstores. Simple. With The Magic Ticket, I’m talking with schools, libraries, grief-counseling centers (because of the Magic Ticket’s subject matter), and yes, bookstores too–but for obvious reasons giving a storytime reading to children is very different from a literary reading to adults. I’m marketing myself more than the book, in a way, and when I pitch the book, I’m pretty much giving the whole story away (it’s only 700 words, after all), opposed to just a glimpse of it (for a 100,000-word novel). At the same time, just as with my last book tour for my novel, it’s all about connections. It’s all about believing in the book.

“[I]t’s all about connections. It’s all about believing in the book.”

For you, what’s it been like to wear two different hats, one business-y (marketing) and one creative (illustrator). And what are your hopes for this book?

It’s both a challenge and a super cool opportunity. I think it gives me the opportunity to think about marketing needs differently because if we want something special for the book like a promo sticker, I can just illustrate it. On the other hand, it’s challenging because I’m not just living in the realm of the illustrator, I’m also balancing all the marketing needs. My biggest hope for this book is that it opens up conversations about loss and grief for both children and parents/counselors/librarians/guardians. Children today are facing so much more grief, whether it’s loss of a family member, or dealing with the consequences of Covid, or dealing with the fear/grief/uncertainty of our world (whether from hearing it themselves, or feeling the uncertainty from guardians). I think that talking about all of that at an early age means that children will feel more able to continue those conversations, and feel their feelings as adults. Or at least that’s my hope.

It’s both a challenge and a super cool opportunity. I think it gives me the opportunity to think about marketing needs differently because if we want something special for the book like a promo sticker, I can just illustrate it. On the other hand, it’s challenging because I’m not just living in the realm of the illustrator, I’m also balancing all the marketing needs. My biggest hope for this book is that it opens up conversations about loss and grief for both children and parents/counselors/librarians/guardians. Children today are facing so much more grief, whether it’s loss of a family member, or dealing with the consequences of Covid, or dealing with the fear/grief/uncertainty of our world (whether from hearing it themselves, or feeling the uncertainty from guardians). I think that talking about all of that at an early age means that children will feel more able to continue those conversations, and feel their feelings as adults. Or at least that’s my hope.

“My biggest hope for this book is that it opens up conversations about loss and grief for both children and parents . . .”

May 4, 2024

THE MAGIC TICKET Kickstarter Campaign is Launched!

We have thirty days to fund David’s book tour! Your donation to his Kickstarter campaign will help David to provide FREE workshops at children’s grief centers to help kids to process their losses through story, just as he did when he wrote THE MAGIC TICKET. Most grief centers and grief camps provide their services for free, so in order to fund the book tour (so David doesn’t have to charge these wonderful organizations for travel and lodging), we’re asking for your help.

If you’d like to contribute, and receive a signed copy of the book in return, please go to this Kickstarter page and pick a donation level you feel comfortable with!

February 13, 2024

I Have Good News! Part 2

Hey, I’ve got more good news!

(Wait, are you reading this first? This is Part 2. Go back immediately and read Part 1 first!)

So here it is: the “big novel” I’ve been working on for years, the EPIC STORY about The Demise of the American Empire as Told Through the Eyes of a Waiter in Yonkers, a.k.a. my greatest accomplishment to date (or perhaps my greatest failure!), a.k.a. nothing less than The Great American Novel I tell ya, a.k.a. the book that used to be 170,000 words long but is now 99,999 words long since my agent told me it needs to be under 100,000 words or no publisher would take it, a.k.a. my literary mainstream novel about a hardworking waiter whose life is shattered by a series of infidelities and tragedies both personal and national, that novel, THE GOSPEL ACCORDING TO DANNY that is, is being published next year (May 2025) by Vine Leaves Press.

I’m revising the final version now (that book cover you’re looking at is not the real cover but just a mock-up placeholder created by my web-savvy friend Paul), but I’m already gearing up for the book tour next year. I’d love to visit your book club, be interviewed on your podcast, visit your classroom, or give a reading at a bookstore, café, or pub near you. Email me to set something up!

[To see when David will be appearing at a location near you, subscribe to the newsletter on this page or bookmark this page.]

I Have Good News! Part 1

Hey, I’ve got good news!

After years of working hard without seeing any results, I finally have some results to share–two results, actually.

First, I wrote a children’s book. Yes, me, David Hicks, the serious novelist of serious literary fiction—I wrote a children’s book, called The Magic Ticket, illustrated beautifully by Kateri Kramer, to be published by Fulcrum Press in July. (You can pre-order here.)

But here’s the catch. I know when you hear “children’s book” you think cutesy or feel-goody. But this one is not.

It’s sad. Somewhat uplifting at the end, but still, it’s sad.

In the words of my agent, “David, this is the saddest f*#@ing book I ever read. I can’t sell it.”

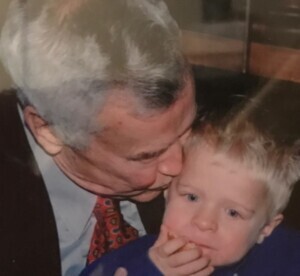

Or in the words of my dearly departed father, “Why does everything you write have to be so sad?”

Because life is sad! my younger self would have responded. But now, my older self would say . . .

Well, I guess I would say the same thing: Because life is sad!

And it’s okay. I’m comfortable with that. Life is also happy, too, of course, but in spurts, and hopefully in the long view, too. But much of life sure is sad. Even when it’s happy, that happiness is usually borne of sadness or loss. It’s earned, in other words. It is relative to any sadness or suffering that preceded it. It doesn’t just happen.

So yeah, I write sad stuff. Sorry, Pops.

And I don’t know how we got to this point, but we really need to stop protecting our children from sad stories. When my wife Cynthia was young, she demanded that her mother read The Little Lame Squirrel’s First Thanksgiving to her, over and over, even though it made Cynthia cry, every time. Because it made her cry. And my son’s favorite film when he was young was about a snowman and a little boy who frolic together all night long (with the saddest damn musical score ever written), only to end with the snowman melted in the morning sun. And my daughter seemed to wallow in sad stories, all of them—as a Pisces, she lived for the opportunity to cry. And still does, only now she prefers horror movies.

And they are the three most beautiful, joyful people I know.

The Magic Ticket is about a boy who loses his sister and is of course devastated, initially. Eventually he finds sanctuary in reading, at first quietly in his room, then at school, then at the public library. Confused about what happened to his sister, forced to be quiet at home with his grieving parents, the boy retreats into a world of stories, a world of books, and in the end, he decides that when he grows up, he wants to write his own book, about his sister.

And yes, if you haven’t guessed by now, that little boy is me.

As a writer, professor, and MFA director, I give a workshop to writers of all ages about the basic structure of stories: “Once upon a time . . . . Then, one day . . .” (In other words, Once upon a time there was a person who lived in a place. Then, one day, something happened. Yep, it’s that simple.) And during one of those workshops, in Salida, Colorado , to preoccupy myself when the workshop participants were writing, I scribbled down my own version of it—the first thing that came to my head:

Once upon a time, there was a happy boy who lived in a happy house with his beautiful mom, his kindhearted dad, his big brother, and little sister.

Then, one day, his sister died.

It seemed a little too obvious. Too simple and too big at the same time. What, no ambiguity? Was this really the main story of my life? If so, why hadn’t I ever written it?

Then, on my last book tour, while at the Moravian Academy in Bethlehem teaching that same workshop to high-school students, I went back to that story, my story, about my sister’s death. Then again at a workshop with adult writers at The Writer’s Center in Bethesda; then with children at the Richmond Young Writers Center; then with adults again at Writespace in Houston; at Charlotte Lit; at Chicago’s Story Studio; and so on.

I realized that for decades, I had been avoiding the most obvious Story of My Life. Sandra’s death had changed everything, at least temporarily—we had gone from a happy family to a deeply sad family all at once; and, believing I had been responsible for her death (I had been sick, and then my sister fell ill, so I assumed she had caught my illness and died from it), I retreated into solitude and silence, crying at the drop of a hat “for no reason” and reading like crazy (books of Peanuts cartoons, at first, but then any book I could find, no matter what the genre, at the Harrison Public Library). I became absorbed in other people’s stories, then continued that absorption as a professor of literature, until finally, decades later, I acquired enough confidence to believe I could write my own story.

But even then, I wrote around my story. Away from my story. The Big Story, that is. The event, you could say, that had made me a writer.

Until finally, while distractedly writing while my students were writing—that is, without really thinking too much about it—I had intuitively set down the skeleton of that Big Story.

As Picasso said, all art comes from the unconscious.

Then, of course, came the revision process—really the learning process, because I had never written a children’s story—and I simply couldn’t have done it without children’s/middle-grade/YA author extraordinaire, Denise Vega; the superb editor at Fulcrum, Alison Auch; my illustrator/co-author Kateri Kramer; my friends Deann Rasch, Ted Downum, and Jim Seitz; and my wife Cynthia, the best editor I know. I was, and still am, way out of my league. But, as always, I’m learning as I go.

So here I am, in a place I never thought I would be. I’m a children’s author! And the story—my story—is sad. But beautiful.

Just like that little boy, so many years ago.

[To pre-order The Magic Ticket, click here: And to follow David’s Magic Ticket Tour, with appearances at schools, children’s hospitals, and libraries, scroll down to sign up for his newsletter, or bookmark this page:]

July 28, 2022

David Hicks Interviewed on WVIA’s “Art Scene” with Erika Funke

She could very well be the Best Interviewer Ever.

She is certainly “The Voice” of the Northeastern PA art scene.

She is Erika Funke, and she very kindly spent some time with David to discuss his writing life, his career, and his work as Director of Creative Writing at Wilkes University.

Give it a listen here.

May 12, 2022

Bohemian Rain

[This post first appeared in DaddyElk.com.]

My father died in January 2007, and at first he seemed to hang around, mostly at the foot of my bed, threatening to twist my toe to wake me up; or across from me at my desk, telling me I might be working too hard; or in my dreams, as angelic as anyone could manage to be in baggy jeans and a sweatshirt. He appeared as the father I had always known, scrutinizing, wondering, observing, offering the occasional wry commentary. But it felt as if he had something to tell me, something parental, something he hadn’t written down in the notes he had left to his loved ones in a sealed envelope in the attic.

My father died in January 2007, and at first he seemed to hang around, mostly at the foot of my bed, threatening to twist my toe to wake me up; or across from me at my desk, telling me I might be working too hard; or in my dreams, as angelic as anyone could manage to be in baggy jeans and a sweatshirt. He appeared as the father I had always known, scrutinizing, wondering, observing, offering the occasional wry commentary. But it felt as if he had something to tell me, something parental, something he hadn’t written down in the notes he had left to his loved ones in a sealed envelope in the attic.

After a while, he disappeared from my immediate surroundings and moved into my dreams, not as the stressed, overworked, loving-but-hard-to-hug man of my youth, but the still-overworked-but-more easygoing father of my adulthood, the man whose happy voice (“Dav!”) would greet me on the phone or whose hand on the back of my head, wordlessly signaling my need for a haircut, conveyed his affection. In my dreams he seemed to enjoy playing a cameo role, silent and supportive, along for the ride, whether the dream was anxious or sports-related or whimsical. Not my actual father, but a more benign and supportive version of him, hovering at the periphery, there if I needed him, with his gentle green eyes and thin smile. Closer to the father I knew when he was in his early seventies, before he died. Closer to the grandfather my children adored. Closer to what we might call an angel.

Then–wouldn’t you know it?–he started popping up in public, in the faces of strangers. At Coors Field in Denver they employ retirees as greeters, and once when I entered the stadium one of them looked me in the eye and said, “Enjoy the game, son.” And when I left, the same man shyly put his hand up for a high-five and said, “How about that Charlie Blackmon, huh?” in the same tone that my father would have used on the phone after watching a Denver sporting event on television: “Did you see Carmelo tonight? How about that shot at the end!”

This kept happening—not with any regularity, but every few months or so: I saw him in the slumped, helpful posture of a security guard; in the thoughtful gaze of the plumber trying to fix the boiler; in the ticket-taker’s welcome at a museum. What all these men had in common was that, like my father, they were (a) tired, (b) pouchy-faced; (c) soft-spoken, (d) happy to be of service, and (e ) kind.

I’m in Prague, on a Fulbright scholarship, and the other day I was on a bus with other scholars and commissioners, traveling from a village called Liblice, where we were enjoying a three-day conference, to a 16th Century brewery in Lobeč. As I entered the bus, I noticed something familiar about the driver, but I sat a few rows back and didn’t think much about it afterwards. It had been a gray day and now the rain was falling, and it continued to fall for the rest of the drive, as well as during the brewery tour, and rain, especially a soft rain, has a way of inviting ghosts and memories. And so as we drank some delicious beer, ate a sumptuous dinner, and toured the facilities , my father kept swimming in and out of my consciousness. In fact, I remember using that word, swimming, in my mind—Hey Pop, what are you doing, swimming around in my brain? Do you have something to tell me?—an appropriate metaphor, I guess, since my father was an excellent swimmer, a lifeguard in his youth, and many of my happiest memories with him took place at the town swimming pool or at a Long Island beach. And all of that led me into a half-reverie, half-memory, while standing in the rain outside the brewery walls, about a day at the beach when I was a boy: my brother and I were tossing a yellow ball back and forth in the surf, and I was swimming out deep to retrieve a throw I had missed, but the ball kept bobbing and drifting out of my reach into the deeper water, no matter how hard I swam, and then it dawned on me that the ball was being pulled by a riptide, and so was I, and the lifeguard’s whistle was blowing and a motorboat was coming for me but then there was my dad—how he had arrived first I’ll never know—grabbing me from behind, treading water with me, telling me to forget the damned ball, and pulling me back to safety.

And then my mind was swimming, and I was looking up at the sky outside the brewery and I couldn’t hear anything the tour guide was saying and all I knew was that I was in the dark twilight of Bohemia and it was raining a little harder now and my dear father, the best swimmer I have ever known, has been dead for fifteen years.

By the time we all climbed back into the bus for our return trip, the sky had darkened, and the rain had diminished to a drizzle. I sat in the front row this time, to the right of the driver, watching him as he nodded kindly to everyone as they entered, as if to tell us he was aware we had all been drinking beer and to reassure us that he had been in the bus the entire time, had exited only to smoke a cigarette in fact, and he would now be delivering us safely back to Liblice. He started the engine, sat patiently until everyone was safely seated, waited a little longer until the road was clear, then steered the large bus down the wet, narrow, country road.

When I got a little choked up, I focused on the wet windshield, on the wide wipers rhythmically swiping from edge to center, from edge to center. Finally I gathered the courage to look back at him.

It’s not so much that he resembled my father—he did, but only a little—but that he felt like him. As in, If Dad were a Czech bus driver, this is the Czech bus driver he would be. My father had spent much of his later life in service of others—as a deli owner he enjoyed making extra-meaty sandwiches for his regulars, and as a security guard, stationed in one of those little shacks at the entrance to a gated community, he happily did favors for the residents, giving them a friendly wave or engaging in a brief chat as they entered and exited. He was the kind of person who enjoyed helping others to get where they wanted to go.

Hey Pop, so now you’re a bus driver?

This, I suppose, is how the dead stay with us. First in our rooms, then in our dreams—always in our dreams—but also through others. You haven’t even thought of me lately, have you. Well surprise, here I am, all the way over here in Bohemia.

What was it, I wondered as I sat on the bus, staring at the driver now, that my father wanted to tell me in the weeks after his death, hovering in the room with me like that? Quit worrying so much. Give Cynthia a kiss. Go easy on the kids. Write another book.

Or maybe it was what he had such a hard time saying his whole life: Son. I love you with all my heart.

As I make my way toward the age my father was when he died, I can only hope that I will, in a manner of speaking, become him, or become a dream of him while still alive, a living, swimming reverie of the man I love.

Until then, I am adrift in some unconscious riptide of mythic destiny, helplessly but willingly surrendering to the inevitable. I am in the ocean, the whole world sparkling in sunshine, and I am clutching his strong shoulders as he bobs in and out of the saltwater, and then my hands are empty, and I’m adrift, and a soft rain is falling and I’m drowning, but then he’s there again, he’s there underneath me, behind me, alongside me, and I swim, alone but not alone, and I gulp the air, but I’m okay.

That yellow ball is long gone, perhaps deteriorated, perhaps still bobbing out there somewhere in the endless sea.

My father is long gone, and I am lost at sea.

But he is never gone, and I will never be lost.

He lives on in me. This is both a recent discovery and a long-held truth. I’ve always been aware that he lives on through my mother, whom he “watched over” after he died; and in my soft-spoken, kindhearted brother; and in my sister, a teacher, helping others her whole life; and in his beloved grandchildren, in whose personalities I see his many influences. But what I am just now realizing is that he lives on in me. Because of me. Through me.

He lives on in me. This is both a recent discovery and a long-held truth. I’ve always been aware that he lives on through my mother, whom he “watched over” after he died; and in my soft-spoken, kindhearted brother; and in my sister, a teacher, helping others her whole life; and in his beloved grandchildren, in whose personalities I see his many influences. But what I am just now realizing is that he lives on in me. Because of me. Through me.

And through others as well. Even in strangers. Even in the Czech Republic, of all places—in the eyes and postures of all the men in their seventies, here and for that matter everywhere, men who quietly go about their business, self-effacing and kind, driving people safely home through the rain.

April 15, 2022

Hicks is a Featured Guest on the “Life And . . . ” Podcast

In a recent “Life And . . . ” podcast, David talked about how difficult celebrating can be when you were raised to think of others over yourself. As an author, David had to learn to celebrate his successes instead of downplaying them. Take a listen here.

In a recent “Life And . . . ” podcast, David talked about how difficult celebrating can be when you were raised to think of others over yourself. As an author, David had to learn to celebrate his successes instead of downplaying them. Take a listen here.

For the hearing-impaired, or for those who prefer reading to listening, his essay appears as a blog post here.

#lifeandpodcast

On the Difficulty of Celebrating

[This essay was first presented on the “Life And . . . ” Podcast in April 2022.]

I’ve always had a hard time with celebrations.

I grew up in a working-class household near the Bronx. My parents were born during the Great Depression, and we lost my sister when I was five; so . . .birthdays, job promotions, weddings, getting A’s on tests, all the kinds of events that typically call for celebration– were modest affairs, somewhat muted, you could say, and tinged with sadness over the empty chair in the room. One Christmas, the ultimate celebration, my brother and I woke up and came downstairs, excited to see all the red-and-gold-wrapped presents under the tree, but my parents were sitting in the corner, sobbing, hit by a sudden wave of grief.

So I grew up quiet. I read books in my room, or at the local library, or on the back stoop. My kind, goodhearted parents instilled in me the values of modesty and humility, to think of others more than myself. Any accomplishment was appreciated, certainly. But not . . . celebrated. Celebrations were the equivalent of boasting, “making a show of yourself.”

My brother and I were the first in our family to go to college, and in my freshman year, I remember being assigned Walt Whitman’s “Song of Myself,” which begins,

I celebrate myself, and sing myself,

And what I assume you shall assume,

For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you.

Well that’s pretty cocky, I thought. Here was this dude, just loafing on the grass, celebrating . . . not the accomplishments of others, or a public event, but . . . .Himself! His mind, his words, his spirit, but also his body–especially his body. “The scent of my armpits,” he says at one point, is an “aroma finer than prayer.”

Get outta here, Walt Whitman I thought, and I shut the book.

Without realizing how much I sounded like my father.

Years later, in graduate school, I returned to Whitman, and had a completely different reaction. Wow, I thought. If only. If only I could write with such confidence! If only I could celebrate my self like this, even just a little bit. I recalled, as a toddler, bringing my stinky feet to my nose, or sniffing my armpits at the onset of puberty, and I understood that what Whitman was advocating was a return to our nature. He wasn’t simply appreciating the natural beauty and sexuality that our parents, teachers, religious leaders and . . . well everyone teaches us to be ashamed of; he was boasting of it, celebrating it, publicly. I learned that he had self-published his book—another form of celebration–, and had anonymously reviewed it, in a celebratory manner—“An American bard at last!” he wrote of himself—and then he had the impudence to sell copies of it on the streets of New York!

And just like that, Whitman was cool. I mean, this was the mid-19th century. Talk about uptight! But in spite of the criticism he received for being so . . . egocentric and brazen and . . . “bestial,” he knew he had worked hard to compose his beautiful and daring poetry, and he was determined to celebrate it, and himself.

I remember walking to church one day with my family, all dressed up—it was probably Easter Sunday, and I was six or seven years old. “My handsome boy,” my mother had called me when she had combed my hair for me. But when we walked past a store window and I paused to check myself out in its reflection, she tugged on my arm. “Don’t be vain,” she said.

This is probably why I ended up working so many blue-collar jobs—sanitation worker, landscaper, dishwasher, busboy, waiter—and working my way through school to become a , teacher, always in service of others, while never once considering doing what I really wanted to do, which was to be a writer. But after a decade or so teaching, I started to feel that old calling, more and more. Instead of talking about writers in class, I wanted to be a writer. Instead of talking about books, I wanted to write my own book. So I started going to readings at the 92nd Street Y, took some creative writing workshops, and finally, in my early forties, after writing a short story and revising it at least fifty times, I sent it to my favorite magazine, Glimmer Train.

Two weeks later, to my amazement, I received a call from one of the editors, congratulating me; they loved my story and had decided to publish it.

Woo-hoo! Time to celebrate, right?

I couldn’t.

I should call someone, I thought. But that would be bragging.

Finally, I called my friend Lauree, a life coach who had been encouraging me to shift my identity from a professor who occasionally wrote to a writer who occasionally professed. “Oh my god!” she said, “How cool! You need to celebrate this.”

When I fell silent, certain that I would not be celebrating this—I had no idea how to celebrate this—she challenged me. “David. Tell me right now how you’re going to celebrate this.”

I muttered something about having a beer with friends, but she didn’t buy it. So I said I needed to think about it, I’d get back to her. But by the time I hung up, she and I both knew it wasn’t going to happen.

Nearly two years later, when the issue finally came out, I opened it with pride. On the cover was an illustration based on my story! And my story, called “Spring Creek Pass,” was the first of the issue, and on the page before it, in the Glimmer Train tradition, was a childhood picture I had sent them, of three-year-old me, sitting with my brother and sister. I thought, she would be so proud of me.

Then I shut the magazine and put it on the shelf.

The year after that story was published, I married the love of my life, and as a Christmas gift, she had that Glimmer Train magazine cover and the first page of my story professionally matted and framed, side by side. When I opened the gift and saw the cover on the left side—depicting a hawk flying over a river gorge, with the snow-covered Rockies in the background—and the first page of my story on the right, with the title and my signature at the top– I was speechless. It was something I would never have thought of doing, and yet, if I had any degree of confidence, that’s exactly how I would have celebrated that accomplishment: by framing it and hanging it on the wall for me to see, every day.

My wife was celebrating me.

Fast-forward ten years: I’d published more autobiographical stories, and arranged them sequentially as chapters of a novel, called White Plains. I’d found an agent, and I had a book contract with a small press called Conundrum, which, like most small presses, had no budget for the promotion, also known as the celebration, of my book. I was now fifty-six years old. Late to the game. I hadn’t celebrated the agent contract or the book contract. Surely I should celebrate its publication, right?

For years, as a professor, writing workshop instructor, and then as director of an MFA program, I had been telling new writers they need to learn how to promote themselves. That publishers aren’t paying for book tours anymore. Why, I would ask the students, did you work so hard to write and revise this book, if not so that people could read it? And how can anyone read your book if they don’t even know it exists? You have to promote it yourself. You have to celebrate yourself.

Now here I was with my own book release coming up. And who knew? It could be the only book I ever published, right?

So, I decided to do it. To go all-out. To beat down that inner voice reminding me to be modest, telling me not to brag. To celebrate my book, in other words. To celebrate myself. To sing myself, even, as Whitman put it.

I planned a 50 stop book tour, with readings all across the country. And in the spirit of Whitman–“every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you,” –at almost every stop, I planned on reading with another writer or two from that city—a communal event. And I would invite everyone I knew in that city—friends, former students, high-school or college buddies—and even some I didn’t know, and afterwards we’d all go out for a beer.

At the launch, at the Bookbar in Denver, I was terrified that nobody would show up. But at least sixty people were there, cramming into the little store, smiling and lining up to buy books.

But before I even got there, before I entered the store and embraced my friends, gave a brief reading, ate two slices of cake with a sugary imprint of my book cover on it, before I drank champagne and signed a lot of books, I had already felt sufficiently celebrated. Because on our way there, my wife and children and I had stopped for dinner, and as I sat with them, the four of us laughing and enjoying each other’s company, out of nowhere, I felt it. This is it, right here. We’re celebrating. Together. Because we did this together. My wife had edited the book, several times, brilliantly. My kids had contributed two moving chapters from their childhood points of view. This was our book. And we were about to launch it together.

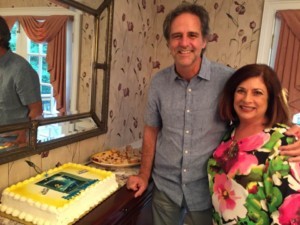

On that epic and oh-so-much-fun book tour, there were several kinds of celebrations, but most were celebrations of friendship—reading with a former housemate in Austin; visiting a book club of twenty-five women hosted by my former babysitter, who had an enormous birthday cake waiting for me; rea

On that epic and oh-so-much-fun book tour, there were several kinds of celebrations, but most were celebrations of friendship—reading with a former housemate in Austin; visiting a book club of twenty-five women hosted by my former babysitter, who had an enormous birthday cake waiting for me; rea ding at a pub in Rochester with college friends I hadn’t seen in thirty-five years; and a stop at a Binghamton diner, for a big breakfast with some old friends, that unexpectedly turned into a celebration when they brought their families and friends with them, took over an entire section of the diner, and made me go out to my car to bring in a box of books for them to buy—a joyous celebration if there ever was one.

ding at a pub in Rochester with college friends I hadn’t seen in thirty-five years; and a stop at a Binghamton diner, for a big breakfast with some old friends, that unexpectedly turned into a celebration when they brought their families and friends with them, took over an entire section of the diner, and made me go out to my car to bring in a box of books for them to buy—a joyous celebration if there ever was one.

And then there was the New York event, at my hometown library, the very library I used to walk to by myself during the lonely years after my sister died. My childhood sanctuary.

When I walked in and saw my family, my old neighbors and high-school friends, even my high-school English teacher, all smiling and ready to buy a stack of books, I had to fight off tears. They had come to celebrate me, but they didn’t realize that so many of them had played a role in making me who I was, and thus had helped to create my story along with me. I told myself to embrace it. Not to be modest and say, “Oh, it’s nothing, it’s just a little book.” I allowed myself to enjoy this celebration of my—our— accomplishment.

Now, looking back, I see that I had to learn not only how to celebrate myself in the most common or superficial way—to toast, to cheer, to publicly revel in an accomplishment, to literally or metaphorically frame it and hang it on the wall—but also in a deeper, more Whitmanesque way: by honoring my craft, my art, my spirit, my SELF, and by adding to this personal celebration a species of generosity and gratitude—which, by the way, pervades Whitman’s seemingly egocentric poem as well.

And now, I understand that I need to share the story of my story with others, to encourage other writers, including those students in my program at Wilkes, to find their own ways to celebrate their work, as I did, and not to succumb to all those negative messages they receive from the rest of the world to mind their manners, keep it to themselves, what makes you think anyone would care? And instead to be proud of their hard work and their talent, and to celebrate it. With pride. With gratitude. With generosity.

So yeah, it took me a few decades, but now?

I celebrate myself, and sing myself,

And what I assume you shall assume,

For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you.

March 9, 2021

How to Pitch Your Book (Guest blog by Jen McLaughlin)

Since I dread being asked, “So what’s your book about?” and am god-awful at answering that question, I invited an expert–best-selling author Jen McLaughlin–to share her secrets with us. Thanks, Jen! — DH

Jen McLaughlin, “Pitching Your Book 101”

Pitching your book to someone else in hopes of publication can be scarier than taking on a genetically mutated, long armed T-Rex while blindfolded with your hands tied behind your back in a Hunger Games arena. When you’re up against something with jagged, deadly teeth, it’s a little hard to feel a little bit like a prey animal…but it doesn’t have to be like that. Believe it or not, whoever you are pitching your book to wants to love your story. They’re as excited about the possibilities as you are, so when you walk up to that table or office and get ready to pour your heart into their extended, cupped hands…here’s some tips to help ease the nerves.

genetically mutated, long armed T-Rex while blindfolded with your hands tied behind your back in a Hunger Games arena. When you’re up against something with jagged, deadly teeth, it’s a little hard to feel a little bit like a prey animal…but it doesn’t have to be like that. Believe it or not, whoever you are pitching your book to wants to love your story. They’re as excited about the possibilities as you are, so when you walk up to that table or office and get ready to pour your heart into their extended, cupped hands…here’s some tips to help ease the nerves.

Be engaging

Enthusiasm is as catching as yawns in a Monday morning eight AM class. If you walk in the room looking as if you’re about to pitch the worst idea ever, you are muddying the waters before you even speak. When you speak about your project, a book that you’ve spent countless  hours writing, examining every single word and comma, and still somehow managing to pull it off without throwing the whole computer out of the window…show that excitement in your words and your pitch!

hours writing, examining every single word and comma, and still somehow managing to pull it off without throwing the whole computer out of the window…show that excitement in your words and your pitch!

Speaking of muddying waters…

Don’t do it! If you start out with “I’m new but I think this is kind of sort of okay” or “I’ve never written before, so it’s probably awful, but let me tell you about it anyway” you’re being your own worst enemy. If you’re not confident in your ability to write yet, well, fake it. If you’re unpublished, no need to state it out loud. The non-mentioning of being a published New York Times bestselling author is more than enough—and that’s okay. Being experienced and published with credentials and degrees is no guarantee that you’re going to get another deal. Being new isn’t a bad thing—own it, embrace it, and show you’re in this for the long haul!

Be casual (but professional)

Don’t be afraid to smile and laugh. You’re selling your book, but you’re also showing your personality and your willingness and ability to work with others. People want to work with peers who are energetic, enthusiastic, and positive. Don’t be so stiff that you could be a stock character. Smile, laugh, learn about the person across the table from you, and most of all—engage. That being said, keep it professional while being engaging. Think of it as a job interview: you want to show you’re easy to work with, knowledgeable, and kind…but you’re not exactly going to swagger in, fling yourself into a seat, slouch, and say, “Sup, man?”

personality and your willingness and ability to work with others. People want to work with peers who are energetic, enthusiastic, and positive. Don’t be so stiff that you could be a stock character. Smile, laugh, learn about the person across the table from you, and most of all—engage. That being said, keep it professional while being engaging. Think of it as a job interview: you want to show you’re easy to work with, knowledgeable, and kind…but you’re not exactly going to swagger in, fling yourself into a seat, slouch, and say, “Sup, man?”

Have an elevator pitch

Every author has four words that they dread: “What’s your book about?” It’s human nature to freeze up when someone asks us this. How can we possibly fit our amazing story into one line such as “A princess has to save an enemy merman prince’s life, and in the process finds out that her whole world was a lie pitched to her by her parents who needed her to hate him” and do it justice? Well, that’s how you do it. Have a strong overall line, and then dive into details such as, “This is a middle-grade fantasy book that plays with themes of hatred, prejudice, independence, and a grand adventure with mermen, kidnapping, sword fights, and a twelve-year-old headstrong princess at the heart of it all…” Does it cover EVERYTHING? Nope. But it shows you know what your book is about, who the audience is, and what the themes are. Once you lay out the bare bones, let the person you’re pitching to ask questions.

What’s an elevator pitch?

An elevator pitch is the idea that an author can, in theory, deliver in the space of an elevator ride. The concept centers around you finding yourself in the elevator with an agent who against all odds asks those four words we spoke about earlier: “What’s your book about?” Obviously, the chances of this happening and you having an agent or editor trapped in an elevator with you for thirty seconds are pretty slim, but the theory still stands today. To pitch, one must have that twenty second description bursting at the seams and ready to be released.

An elevator pitch is the idea that an author can, in theory, deliver in the space of an elevator ride. The concept centers around you finding yourself in the elevator with an agent who against all odds asks those four words we spoke about earlier: “What’s your book about?” Obviously, the chances of this happening and you having an agent or editor trapped in an elevator with you for thirty seconds are pretty slim, but the theory still stands today. To pitch, one must have that twenty second description bursting at the seams and ready to be released.

Fine. How do I write one?

Try to make it be 20-30 words (or less!).Be enthusiastic and confident. This is your story—own it!Make it memorable – “The ghost of a teenage girl must discover who killed her before she runs out of time to accept her offer into one-time offer into heaven” or “A teenager is forced to enter a fight to the death to save her sister, and becomes a symbol of freedom in a war she didn’t ask for.”Your pitch should leave the listener asking for more. It should be unique, engaging, compelling, and intriguing. The best response you can possibly get is: “Tell me more!”If you have publication or education creds, mention them briefly

The key word being briefly! If you spend your whole pitch talking about yourself, you missed the opportunity to hook them into your story. Instead, focus on your 20-30 word pitch, and at the end you can add a line such as “I have over fifty books published, some of which have hit the New York Times, and an MFA in Creative Writing.” That’s literally the absolute most you should mention, as you’re not selling yourself so much as you’re selling your amazing idea that you took from blank screen with a blinking cursor and turned into a real life, living, breathing (yes, books breathe!) story that has the potential of being their next investment. You are just the footnote to the tale, and again? That’s okay.

Above all, don’t lose hope

Stephen King threw Carrie in the trash after receiving too many rejections, and now he’s one of the most recognizable names out there. Writing comes part and parcel with rejection, but it’s not the end of your writing career if a book doesn’t sell. Dust off that burden on your back, roll your shoulders, open up that computer, and glare at the blinking cursor. After a moment of reflection, rest your fingers on those keys that you can feel against your fingertips even as I type this, nod your head, and get back to it. Writers don’t have the luxury of giving up. We just keep on going, telling the world our stories, and hope for the best…

Kind of like our characters.

About Jen:

Jen McLaughlin is the New York Times, USA Today, and Wall Street Journal bestselling author who was mentioned in Forbes alongside E. L. James as one of the breakout independent authors to dominate the bestselling lists. Under her pen name Diane Alberts, she is a multi-published, bestselling author of Contemporary Romance. She is also published as Jen McLaughlin by Penguin/Berkley and Random House and has written 3 books for James Patterson/Hachette. A firm believer in chasing your dreams, Jen went back to school for her MFA when her daughter started college and is now a college professor. She also works as an assistant in the Honors Program while also teaching Creative Writing at the University level and is currently pursuing her Doctorate of Education. Jen lives in Pennsylvania with her husband, four kids, one dog, and five cats. You can visit her site at https://jenmclaughlin-dianealberts.com.