Sharon Bala's Blog, page 2

September 20, 2023

Aliens

Earlier this year, I read a historical fiction about a young brown girl in a British boarding school. The perspective was close third person. The inner life of the protagonist was central to the story. In the opening chapter, the character wakes up, looks at herself in the mirror, and dwells on disparaging thoughts about how “swarthy” and “dusky” and “dingy” her skin is, how different she is from the other girls at school. And then she continues to have these othering thoughts about herself, obsessing over whether or not she is a “true Briton.” I have been a brown person in all-white spaces (hi, rural Newfoundland!) and I’m a sucker for stories set in Victorian England. I should be the ideal reader for this book. Instead, I felt alienated. Whose gaze is that in the mirror? It’s not the gaze of a brown character. It’s the gaze of the white author. A white author who perhaps - let’s be generous - tried their level best to get into the skin of brown character and failed.

I’ve been trying to forget this infuriating book exists but I was reminded of it again when I read Yellowface. In a scene mid-way through the book, the main character June is asked - by a Chinese-American reader - why she thinks she (a white woman) is the right person to write and profit from a novel about indentured Chinese labourers.

Sometimes this issue of identity and imagination is framed as: who has the right to tell a story? It’s the wrong question. Instead, the more crucial questions are why and how? Why am I drawn to this particular point-of-view? And how am I going to ensure the characters and their tales are authentic?

In tandem with Yellowface, I was reading Brown Girls by Daphne Palasi Andreades, a first person plural novella that follows a group of girls from the time they are about 10 well into adulthood. It’s Julie Otsuka’s Buddha in the Attic meets Queen’s, New York. The book’s titular girls are Black, Muslim, East and South Asian. They are straight and queer and some of them, it turns out, are not girls. Unlike many of the characters, the author is Filipino. Yet her characters rang true and their experiences and quandaries and thoughts all felt comfortingly, disconcertingly familiar. Palasi Andreades has spoken of setting the novel in her hometown where she was surrounded by girls like the ones in her story. Her expertise shines through in her characters.

White authors can and do write authentic brown characters, characters whose interiority is easy to sink into and whose stories I deeply enjoy. Jacinta Greenwood in Michael Christie’s Greenwood is an excellent example and so is Adam Foole in Steven Price’s By Gaslight.

I’ve gotten quite used to not finding myself in a lot of fiction. So when I see a character who looks a little like me - or my cousin/ father/ grandmother - I sometimes feel apprehensive. Like the only brown girl in an all-white school. How’s this going to go?

The best fiction envelops the reader, makes them feel at one with the characters. But when the author does a shoddy job the result is a poor ventriloquist act, a puppet with a brown face parroting a white writer’s (let’s be generous, again) unconscious bias. And the reader who should identify with the protagonist is, instead, expelled.

September 8, 2023

Yellow

No more novels about writers writing books, I swore. And then I read Yellowface by R.F. Kuang. Yellowface is the story of two authors. Athena is Asian and hugely successful. (I kept thinking of Zadie Smith, getting that mega publishing deal while she was still at OxBridge. ) June is white and midling. When Athena dies, June takes her unpublished manuscript - about the Chinese Labour Corps in WWI - and passes it off as her own. Spoilers ahead.

This book should be on the curriculum in every publishing house and MFA program because even though it’s a novel, and supposedly fiction, most of what’s on the page are facts.

Exhibits A&B:

“Publishing picks a winner - someone attractive enough, someone cool and young and, oh, we’re all thinking it, let’s just say it, “diverse” enough - and lavishes all its money and resources on them” (p. 5/6.)

“… the books that become big do so because at some point everyone decided, for no good reason at all, that this would be the title of the moment.” (p. 79)

Some of the most damning parts of the book are the passages where June and her editors hack away at Athena’s draft, making the whole thing more palatable to white readers, squeezing it into the corset of the western narrative tradition, which prizes a straight forward tale of a hero’s journey.

Athena’s manuscript is described as “an echo from the battlefield” (p. 27) layering “disparate narratives and perspectives together to form a moving mosaic… a multiplicity of voices unburying the past” (p. 28). She’s the kind of writer who makes the reader do a little work. One assumes there are no glossaries or italics around the Chinese words. I thought of Madeline Thien’s brilliant Do Not Say We Have Nothing. I thought of so many books by Asian and Indigenous authors that are capacious, allowing a plethora of characters and narrators inviting all their stories into the frame. Someone, I’m sure, has written a dissertation about this… how our stories are communal because our societies are too. Ironic then that exactly what drew June to the book are the very things she excises.

And none of this is fiction. It happens every single day. Editors and agents and well-meaning creative writing instructors, pushing writers-of-colour to whitewash their stories. Include a glossary. Westernize the names. Add explanatory commas. And, when that proves to be a pain, lavishing book deals and bigger advances on white writers whose books cover the same terrain and aren’t so “difficult.” At one point, June’s editor is amazed by how quickly she agrees to make changes, writing “You are so wonderfully easy to work with. Most authors are pickier about killing their darlings” (p. 45). But of course. Why should June be precious about axing what isn’t hers?

Still, though, it’s impossible not to feel bad for June. Because Yellowface is brutally honest about fragile writerly egos too. Even after June hits the NYT best seller list and quickly earns out her massive advance, she is unsatisfied, obsesses over online reviews and commentary, and drives herself up the wall with self-doubt. Her vulnerability is painfully relatable. The reader - who is also a writer - roots against her and identifies with her. Neat trick.

This novel is American Dirt meets Cat Person meets Bad Art Friend meets Lionel Shriver in a sombrero meets the Appropriation Prize. Yellowface is more than just a fun read. Yellowface is catharsis. Here finally is everything we have all experienced and been bitching about (mostly quietly, privately, amongst ourselves) for years. And not just in any novel but in a massively successful, Reese’s Book Club pick, book, one of those chosen few that the publisher (rightly) decided was going to be a hit. Can’t wait until they make it into a movie staring Constance Wu (who blurbed the book!) and ScarJo.

September 1, 2023

Cozy murder mystery

Shehan Karunatilaka’s 2022 Booker-winning novel The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida is an absurd life-after-death romp about a young man who, against the better judgement of wiser ghosts, goes in search of his killers. It’s a whodunit set in Sri Lanka in the late 80s, during the civil war. It’s irreverent, unsentimental, and uproarious.

At one point I was reading on my deck, laughing uncontrollably. My neighbours were like WHAT is so funny? But here’s the thing… it’s impossible to explain. Part of my glee has to do with language. Karunatilaka sprinkles in Sinhala words here and there - without italics or explanation, hallelujah - and for once I, a famously unilingual person, actually understand. Here’s what I was laughing at: Boru Facts.

Boru means lies and just seeing this word, that I’ve never seen before in print, caused an immediate dopamine hit. It conjured up memories of my mother’s voice. Boru. As children we were forever telling, or being accused of telling, lies. Layered over my mother’s voice are uncles and aunts, shouting and laughing, cutting someone off mid-sentence to exclaim: Boru! Because when the adults got together to reminisce or gossip, the accusations of exaggeration and fabrication flew. Boru means lies but it also means bull shit, I guess. I don’t know. It’s difficult to translate, especially when my Sinhala is at the level of a slow witted six year old. Six is when we moved to Canada and stopped speaking Sinhala in the house. Sin, no men?*

It’s not only that I understand the novel’s second language, it’s that the Sinhala is imbued with auditory memory, making the book feel familiar and homey. Did I just call a novel about a young man who spends his short life travelling around a war zone, taking photos of men, women, and infants being butchered, only to be killed himself, then chopped into pieces and thrown into a putrid lake, cozy? I did. Yes.

When a book is written for you, it feels like home. And even though the novel helps the reader along - for example, with humorous lists that break down the acronyms and political divisions - a lot is left untranslated and unexplained. It’s one of the great strengths of the book, the author’s confidence, that he trusts the reader to do some of the work.

In an interview, after winning what is arguably the most important literary prize in the western world, Karunatilaka said he had trouble finding an international publisher. “A lot of them passed on it, saying that Sri Lankan politics was quite esoteric and confusing. Some said that the mythology and worldbuilding was impenetrable, and difficult for Western readers.” Boru facts!

*Why do Sri Lankans add the word men to the end of random sentences? Who knows, men.

July 10, 2023

Repeat. Repeat. Repeat

Grain Magazine is celebrating its 50th birthday and I was the prose guest editor for the upcoming anniversary issue. I sifted through a couple hundred fiction and non-fiction submissions and selected just over a dozen for publication. (Pro tip: sometimes these special issues are larger than usual and more pages = more acceptances.) One weakness I noticed, even in the strongest pieces, was repetition. Over and over and over again. (See what I did there?). If you’re fine tuning your own writing, here are four things to watch for:

Commonly, it’s individual words. For example, the word surprise or look or choose showing up three or four times in a paragraph.

It could be a specific description: the grandfather clock keeping the beat like a metronome. Finding the simile once is delightful but twice reads as a mistake.

Beware the synonym list. Do you really need four words when one will do?

Have you said the same thing five different ways? This form of repetition is the most difficult one to spot, often because it’s camouflaged by beautiful prose.

Repetition is a tool that can be used to great effect. Try to be intentional. And delete the rest.

July 3, 2023

The best

Speaking of highschool…

This winter, I juried the Youth Short Story Category, which is part of the Amazon First Novel Award. And then last month, The Walrus threw a celebratory bash at the top of the Globe & Mail building in Toronto. It’s gorgeous up there - wide open space, huge windows, a massive terrace with a view of downtown, long bar, the works. The six teen finalists were present but you know what? I was almost more thrilled for their gobsmacked, camera-happy parents.

Toward the end of the evening, one of the young writers asked me an impossible question: what made the winning story stand out from the rest? She’d read the entries by previous years’ finalists and couldn’t figure out what set the winners apart. (Teenagers are terrifying and wonderful, aren’t they?) I don’t know what I stammered out but I’m sure it was all wrong.

Every story on that shortlist was exceptional. One piece about a relationship between two young women was wise beyond the author’s years. Another had such perfect prose, I googled lines to make sure it wasn’t a theft. One had a confident, funny voice. One bared its complicated emotions without shame. Another put its anger right on the surface. And the winning story was inventive, like nothing else I had read in the hundreds and hundreds of submissions. And on that particular day, on that particular Zoom meeting, we decided to reward originality. On a different day a different jury would have made a different choice.

What are the criteria for “best”? These decisions are always made by taste and stupid luck. The thing I want to say to young writers is that creative writing is not calculus or a spelling test. There is no equation. There is no right answer. There is only your imagination and your authenticity. Tell the story only you can tell with all the honesty you can possibly muster. Don’t try to win. Try to write.

(Photo of the jury and finalists for the Amazon First Novel Award and the Youth Short Story Category, courtesy of the Amazon First Novel Award and The Walrus)

June 26, 2023

Highschool

In highschool I had a couple of friends on the improv team. For a couple of years they were on a hot streak - going so far as to compete and win at Nationals - and I was a groupie. Their main competition was the team from Cardinal Carter, a rival Catholic school in York Region. It was the heyday of The Simpsons and I’m sure we made the requisite Shelbyville jokes. Maybe they did too.

I hadn’t thought about improv or highschool in ages. But then a teacher from Cardinal Carter sent me photos. Students in their uniform kilts and sweatshirts (go Cougars!) sitting on the floor by a locker bank, desks forming a circle in a classroom, engaged in conversation, copies of The Boat People nearby.

First of all, I’m impressed. These are grade 11s - how old are they? 15? 16? - reading a 400 page, thinly veiled refugee law text book. At their age I was reading Salinger and snickering at Holden Caulfield’s potty mouth. The Shakespeare on the cirriculum that year was Romeo and Juliet. Which. Real talk. R&J is the most accessible of Will’s plays. We went to see Baz Luhrmann and called it a day.

At Cardinal Carter, the grade 11s are engaged in something called a Socratic Seminar. I don’t know what that is but I love the sound of it. The Socratic Method is how I like to engage with work-in-progress. I imagine them interrogating the book, each other, and their own morality, fumbling toward answers or possibly deeper questions. I hope they are thinking beyond the fictional characters and considering the real world and present day concerns, and how they will cast their first votes.

March 28, 2023

In defence of cliches

Hear me out. You’re drafting and deep in the zone, trying to get as much down as possible before the trap door opens to eject you, and in the rush to get to the end of the idea/ scene/ story/ passage/ novel, you write a can of worms, a sea full of fish, or a wicked stepmother. Cliches, yes. But neither trite nor lazy. Not yet. At the moment they are merely shortcuts.

I describe it like this to clients: You’re not just crossing unknown terrain, you’re creating the land as you go. And the first time across, the goal is to get to the end. Along the way you might drop flags in the ground, markers of places where you need to return and fine tune. Maybe add an oasis in this desert; get specific about the flora and fauna in this forest.

In an early draft, most cliches are markers. The trick is to return to them later and replace with more inventive prose.

And sometimes the cliches are hardworking and earn their place in the story. For example, when upended - the hooker with the heart of gold turns out to be an opportunist and also he’s not a hooker. Think of office jargon and how it can be used in a scene to convey the deadening nature of interminable meetings. Or dialogue! The plentitude of fish in the sea becomes a tragic-comic joke when used in a conversation between a meddling uncle and a newly single woman.

Cliches, like other maligned aspects of craft - telling, adjectives in dialogue tags, and so on - are a tool. Be judicious and intentional about how and when you use them.

March 20, 2023

Math lesson

I was telling Tom about a story that began with too many characters. “This needs to get pared back,” I said. “Yeah, yeah, there can be twenty people milling around the Loblaws when the axe-wielding clowns storm in, but only two or three get names. All the others have to fade into the background or it’s overload.”

“Yeah,” he agreed. “It’s like this paper I read the other day. It began with 18 cohomology classes, introduced one after the other. It was like….” Then he rolled his eyes and made a frustrated pffft noise, because who can keep eighteen cohomology classes straight?

Theoretical math is fiction writing with better funding. Sometimes Tom reads a proof and declares it “elegant” in the same way I might read a short story by Alexander Macloed or a passage from Richard Wagamese and call it sublime. And other times he shoves a page of hieroglyphics at me and says “Look at this!” Then he makes a barfing noise and complains “Okay, maybe this guy understands what all this blah-blah means but that’s no way to write for a reader.”

What makes for strong writing in math? I asked. Everything serves a purpose. It ties together. There’s not a lot of extraneous stuff. Importantly: there is clarity.

February 16, 2023

Eulogy

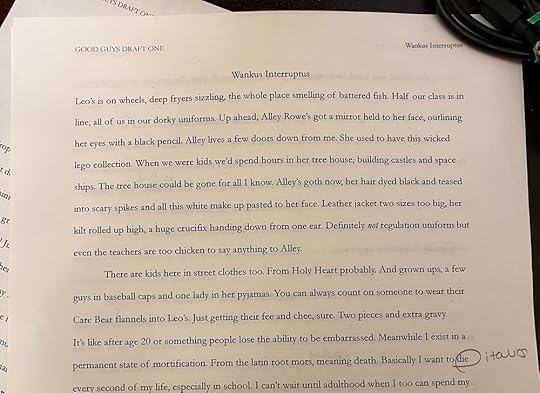

The story was titled Wankus Interruptus, and when I first read those words, centred at the top of the page, I paused. (Do you know this feeling? A fleeting fuzz of nostalgia. A whiff of emotion. In this case, the top note was humour.) The phrase was familiar. Why? And in the next second I recalled.

The page with the enigmatic title, sat on top of a sheaf that was being used for tinder. It came from deep in a box of cast offs - flyers, print outs, egg cartons, effigies of our enemies - that we keep for this purpose. We’ve had issues with our chimney and even bigger issues getting someone to come and repair the damn thing, and for a couple of years now, the wood stove has sat unused. But this week, in an attempt to conserve heating oil (itself a tedious chapter in the long and boring story called Homeownership) we’ve had fires blazing every day.

Wankus Interruptus isn’t a story. It’s the title of a chapter. Was the title of a chapter. Is the title of a chapter? What tense should one use about a manuscript that lies cold in the necropolis of murdered darlings?

Anyway, this chapter was from the first person point of view of a fourteen- year-old boy. It was set in the 90s in St. John’s and I spent ages researching what the city looked and felt and sounded like in those years. And then I had to do a bunch of work to conjure up a teenage boy and find his voice. First person is exacting!

I wrote and revised a whole draft of this novel. A couple of drafts. I scored a Canada Council grant, an ArtsNL grant, and a municipal grant for this novel. Somehow my agent sold this novel. Yaddha. Yaddha. RIP to that novel (2018-2020). After a long spell in the recycling bin, it’s finally being cremated. Later, the ashes will be scattered under the deck where my silly dog will no doubt roll in them.

February 6, 2023

Take the wheel

In my 20s, I took up pottery. The classes were held in a shed, at the bottom of a blousy garden, where three of us students hunched over our wheels while our instructor walked around in an old pair of dungarees and chatted about the raccoons who were terrorizing her household.

Pottery is a physical act; you have to put your whole body into the effort if you’re going to keep the clay centered. More often than not, we novices found the clay controlled us, spinning itself in unexpected ways. A bowl stubbornly flattening into a plate. A vase becoming a mug. A mug shrinking to a pinch bowl.

Our instructor, a professional potter who’d been at this two or three decades, praised our creations, claimed there was a looseness to inexperience that experts could never replicate. I thought she was just being kind. Now, I know better.

Most of my clients have had little, if any, formal instruction in creative writing. They write instinctively, with the particular freedom that comes from not knowing the so-called rules. Unfettered by the shoulds and musts and can’ts, their stories are ambitious and experimental and interesting, uninhibited in the way mine used to be, with an unaffected playfulness I can’t recapture.

One thing about new writers: they are often surprised when I point out what they’ve written. In the same way my attempts at vases ended as miniature plant pots, there’s often a gap between the story the writer intended to tell - or thought they were telling - and the one they actually wrote. Without fail, the unintended story is the juicier one. Sometimes it winks out from the subtext. Sometimes it’s right there in black and white but the writer hasn’t noticed.*

The conscious brain is censorious. The subconscious though? Oh, she knows how to spin a yarn. This is true for experienced writers too. (A couple of months ago, after reading a draft of my new novel, my writing group pointed out that one of its central anxieties is money. Huh, I said. You’re right.) The only difference is experienced authors know the unconscious is also at work and, if we’re smart, we’ll lean into whatever gifts it might offer.

When I first start working with a writer I always give some version of this speech: You are in the driver’s seat. I’m only riding shot gun. I have a map. It might not be the correct one. I’m going to make suggestions but you make the calls. Lately, though I’ve been thinking I should amend this pep talk. Let the story take the wheel for a while. Find out where it takes you.

*You don’t need to spend a cent to find out what you’ve written. Ask someone you trust and who has never heard you talk about your work (that part is crucial. It must be a reader who is coming to it fresh and has no preconceived notions about the plot or characters or theme or what you are trying to do) to read what you’ve written and then tell you point for point what happens in the story and what it’s about.

But if you do want professional guidance, I’m here.

Sharon Bala's Blog

- Sharon Bala's profile

- 140 followers