Susan Bernofsky's Blog, page 38

November 17, 2015

Submit Now for the Cliff Becker Book Prize in Translation

Cliff Becker

This is the fourth year of the annual Cliff Becker Book Prize in Translation, created to honor Cliff Becker, who was the much-beloved director of literary programs at the National Endowment for the Arts until his untimely death in 2005. To compete for the prize, translators are invited to submit bilingual manuscripts of translated poetry postmarked by Nov. 30, 2015. The prize comes with a $1000 purse, and the winning manuscript will be published by White Pine Press. I see the name of the final judge hasn’t been announced yet, which is a bit odd, but surely it will be forthcoming soon. Submission details and more information here.

The post Submit Now for the Cliff Becker Book Prize in Translation appeared first on TRANSLATIONiSTA.

What I Learned at ALTA 2015, Pt. 1

Matvei Yankelevich discusses the art of the mistake

This year’s ALTA (American Literary Translators Association) conference in Tucson, AZ was one of the best-attended in recent history, with initial estimates of around 370 attendees. Unfortunately I didn’t arrive until Thursday evening, so missed the ALTA Fellows‘ reading (and indeed all the Thursday programming that preceded it), but did manage to catch the announcement of the 2015 ALTA awards. In the two days following, I attended a few really interesting panels (which I report on below), and missed others I’d have loved to see because of schedule conflicts. There were other sorts of conflict as well – I witnessed several exchanges that made me aware of the generational divide among translators in interesting ways.

The first panel I attended was The History of Translating Contemporary Arabic Literature put together by Asmahan Sassah. The panel began with an excellent generation-bridging presentation by freshly crowned NTA winner William Hutchins in which he provocatively announced that 9/11 didn’t really change anything in the reception of Arabic literature in the United States. Instead, he described what he sees as a series of five significant developments/paradigm shifts:

The transition from Orientalist studies to Centers for Middle Eastern Studies beginning in the 1950s, shifting sensibilities from universities outward;

The Nobel Prize to Naguib Mahfouz, massively increasing international awareness of and interest in writing in Arabic.

The advent of the Internet, suddenly making it easy for authors and translators to communicate directly. Hutchins told some entertaining pre-Internet stories about sending friends to hand-deliver messages when he needed to reach an Egyptian author he was translating.

The disintegration of the Middle East – meaning that many authors now live in exile or are endangered within their own countries. He said he works with three Yemeni authors whom he avoids contacting directly for fear of worsening their situations.

As a sort of corollary to #4: With some of Hutchins’s translations getting on shortlists, longlists and winning prizes in the English-speaking world, it sometimes happens that the works he translates get much more attention and readership in English than they did in the Arabic originals, an odd imbalance.

Another panelist, Matthew Chovanec, studied the contenders for and winners of the International Prize for Arabic Fiction (often referred to – erroneously – as the Arabic Booker Prize). He expected to find books that had been politically and/or culturally vetted for acceptability, and found few signs of this, though he noted that the winning books tend to have a high “readability” quotient. He did, however, find that in general most reviewers of these books seemed oddly hesitant to criticize anything about them at all (even in the case of the 2014 winner, Frankenstein in Baghdad, a work apparently not without its flaws).

In the second half of the panel, Reemah al-Urfali issued an impassioned plea for translations to stop pandering to Western feminism by presenting Arab women as victimized and oppressed, in a manner emphasizing erotics and violence. She concentrated on the 2005 Feminist Press edition of Alia Mamdouh’s novel Naphtalene, set in 1940s/1950s Baghdad, which appeared with a foreword by Hélène Cixous and was presented as precisely the sort of storytelling al-Urfali is objecting to. She said she much preferred the original title (Mothballs) under which the book appeared as part of the Arab Women Writers series put out by Garnet in the U.K. (Naphtalene, the chemical name, makes for a too-easy association with the chemical warfare readers might have with present-day Iraq.) Al-Urfali didn’t mention the translator of either edition, and I was surprised when I looked the books up and saw that both were in fact by same translator, Peter Theroux; her argument was more about the book’s packaging and selection than how it was translated. Overall, I found that she made good and strong points, though it’s an odd lapse not to discuss a book’s actual translation at a translators’ conference.

Her contribution had an interesting aftermath as well, when an older translator – without acknowledging anything al-Urfali had said – spoke about his own translations in unapologetically orientalist terms, saying for example that he was drawn to translate the work of both contemporary Palestinian writers and Chinese poets during and just after the Cultural Revolution because “Good literature happens when people are under stress.” Now, just because someone says things like this doesn’t mean that his engagement with/knowledge of these literatures is not extensive. It’s just that it would be really unlikely for someone who’s paid attention to the impassioned debates in recent decades about colonialism and all its accompanying ills to draw a direct connection like this between aesthetic pleasure and accounts of suffering in the context of armed conflict. My takeaway: It’s really important to pay attention to the issues that intelligent people 20 or even 40 years one’s junior are exercised about.

Leading me to the next terrific panel I attended: Wrong Turns: On Making Mistakes in Translation. The topic was apparently of enormous interest – there were 90-100 people already crammed into the room when I arrived. And the panel was indeed highly entertaining and productive. As moderator Karen Emmerich put it, the concept of the “mistake” is so interesting because it gets used to “police the borders” between different approaches to and attitudes toward translation. After all, a mistake can be “either funny and generative, or devastating,” depending whether we’re looking at “correctness” from the point of view of responsibility or play. Heather Cleary reported on why the Buenos Aires Review, of which she is a founding editor, decided to present the texts it publishes bilingually in such a way that you have to toggle between the English and Spanish versions, to discourage the sort of back-and-forth reading that tempts one to constantly “check” the translator’s work rather than engage fully in the text as a reader. Because let’s face it, we do have a tendency to become translation fact-checkers when we read, and it definitely affects our engagement with the text. She also mentioned in passing an interesting website with a quite different aim: www.doppeltext.com, which provides (for a fee) stories in French, German, Russian, or Spanish with English translations programmed to appear one phrase at a time when you click on a line; Kafka’s Metamorphosis (in the Ian Johnston translation) is offered as a free sample. On the same panel, Matvei Yankelevich spoke about the different ways correctness gets parsed in different context with a really interesting discussion of why he decided to translate the text formerly known as The Cloud in Trousers by Mayakovsky as The Cloud in Pants. We’re drawn to the alliteration of cloud/trousers, he explains, because it’s lyrical, and so we identify it as “literary.” But in fact Mayakovsky wasn’t at all interested in sounding literary (there’s no alliteration in Oblako v shtanakh, for one thing), in fact he was all about dismantling lyricism, so “correcting” his work to make it sound more poetic is wrong. Right. The rightness of “mistakes” was most powerfully illustrated on this panel in the presentation by David Shook, who provided various examples of intentional and inadvertent mistranslations that wound up revealing previously hidden truths about a literary work (as when “eau de cologne” in his translation of “Cook Boat” by Joaquín Pasos became “colonial waters”). In another project, “Writing Lessons for the Dead and Blind,” he translated a work by Mario Bellatin (with whom he had previously collaborated) that didn’t yet exist in the original. That’s a great way to avoid translation errors. (And let me not fail to remind Marian Schwartz of her suggestion in the Q&A that someone organize an ALTA panel next year on which languages and cultures are most hospitable to, and which most resistant to errors. She noted that some poets like their translators’ mistakes and insist on keeping them.)

Translators hypnotized by punctuation

Next it was on to The Perils of Punctuation, at which I was a presenter, filling in for the originally-scheduled Jeffrey Buntrock. Lisa Bradford started the panel off with a lovely presentation on her just-out translation of Juan Gelman’s Oxen Rage that ends on an interrupted question mark (a question mark having ¿two parts? in Spanish). Aviya Kushner spoke about the history of punctuation in translations of the Bible (noting that the Hebrew Bible uses none). It turns out that quite a few declarative sentences e.g. in the Psalms get turned into questions in translation – that’s rhetorically really interesting. Aron Aji talked about the transformations of the Turkish language and is punctuation, noting that modern Turkish is only around 90 years old, before which it used the Arabic system and no punctuation at all, such that Turkish punctuation remains unstable to this day, with e.g. different newspapers using slightly different systems. Marian Schwartz taught us all the different things a colon can do in Russian that it cannot in English (there are lots of them, e.g. it can substitute for a period in English, or for a pair of m-dashes, or to introduce a subordinate clause, or to introduce a direct quote in response to a reported question, or for “because”). My own presentation also talked about the slippage between words and punctuation (with regard to the German word “denn,” a weak-causality form of “because” that’s often best translated into English as a punctuation mark). I talked about German usages (the run-on sentence and heavy use of exclamation points in particular) that require retooling in English. Like Marian, I emphasized the helpfulness of the dash as a sentence-saving translator’s tool in English. And I very much admire the point Marian made that we should always remember, when translating, that we are translating whatever it is that is special in the prose of each author and not the stylistic peculiarities that are universal to the language in which the author writes. Yes, important point.

There’s lots more I learned at ALTA this year – much more than will fit in a single blog post, so I’ll truncate here and resume my report in a second post to follow soon.

The post What I Learned at ALTA 2015, Pt. 1 appeared first on TRANSLATIONiSTA.

November 16, 2015

Translation on Tap in NYC, Nov. 16 – 30, 2015

Early November was crowded with events, and now we’re settling in for a calmer end of month, but you won’t want to miss this:

A Public Space presents translator Aviya Kushner talking about her new book The Grammar of God, an investigation of the Hebrew Bible and how language shapes belief, looking at (among other things) lots of different Bible translations. I heard her talking about some of this at ALTA the other week, and it was truly fascinating. More information here. A Public Space, 323 Dean St., Brooklyn, 7:00 p.m.

Saturday, Nov. 21:

Translation Matters: A star-studded team of translators and translation scholars/theorists gather to discuss “translation as a psychic, aesthetic, and cultural phenomenon.” With David Bellos, Bella Brodzki, Suzanne Jill Levine, Mark Polizzotti, and Michelle Woods. More information here. The Helix Center, 247 E. 82nd St., 2:30 – 4:30 p.m.

The post Translation on Tap in NYC, Nov. 16 – 30, 2015 appeared first on TRANSLATIONiSTA.

October 29, 2015

2015 ALTA Prizes Announced

Greetings from Tucson, of which I have seen, so far, only the airport, the highway, and the American Literary Translators Association conference hotel, but I wanted to lose no time in letting you know the winners of the four ALTA prizes that were announced this evening at the conference – which, by the way, has record attendance this year: there were at least 350 people there in the hotel ballroom when the awards were given out, creating an excellent standing-room-only effect. It went well with the seasonal treat of pumpkin-stuffed tacos (quite tasty, in fact).

Greetings from Tucson, of which I have seen, so far, only the airport, the highway, and the American Literary Translators Association conference hotel, but I wanted to lose no time in letting you know the winners of the four ALTA prizes that were announced this evening at the conference – which, by the way, has record attendance this year: there were at least 350 people there in the hotel ballroom when the awards were given out, creating an excellent standing-room-only effect. It went well with the seasonal treat of pumpkin-stuffed tacos (quite tasty, in fact).

All right, enough shilly-shallying. Here’s who won prizes this year:

The Lucien Stryk Prize for translation from an Asian language went to Eleanor Goodman for her translation of Something Crosses My Mind by Wang Xiaoni (Chinese), published by Zephyr Press.

The Italian Prose in Translation Award went to Anne Milano Appel for her translation of Blindly by Claudio Magris, published first by Penguin Canada and then by Yale University Press.

A total of 120 titles were submitted for the two National Translation Awards this year. The winners who beat the odds were:

In Prose: William M. Hutchins for his translation of The New Waw: Saharan Oasis by Ibrahim al-Koni (Arabic), published by the Center for Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Texas at Austin.

In Poetry: Pierre Joris for his translation of Breathturn into Timestead: The Collected Later Poetry by Paul Celan (German), published by Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

Congratulations to all this year’s winning translators!

The post 2015 ALTA Prizes Announced appeared first on TRANSLATIONiSTA.

October 28, 2015

2015 Italian Prose in Translation Award Shortlist

The American Literary Translators Association (ALTA) has just announced the finalists for the inaugural year of the Italian Prose in Translation Award. The winner of the prize will be announced during this year’s ALTA conference, which is being held starting this evening in Tucson, AZ. If I have understood correctly, this means we’ll know who won the prize tomorrow evening. So enjoy this shortlist while it’s still fresh out of the oven, and stay tuned for the big announcement soon! The full schedule for the conference is here – see you there?

The American Literary Translators Association (ALTA) has just announced the finalists for the inaugural year of the Italian Prose in Translation Award. The winner of the prize will be announced during this year’s ALTA conference, which is being held starting this evening in Tucson, AZ. If I have understood correctly, this means we’ll know who won the prize tomorrow evening. So enjoy this shortlist while it’s still fresh out of the oven, and stay tuned for the big announcement soon! The full schedule for the conference is here – see you there?

Here’s the list:

The Day Before Happiness by Erri de Luca, translated by Michael Moore (Other Press)

A Pimp’s Notes by Giorgio Faletti, translated by Antony Shugaar (Farrar Straus and Giroux)

My Brilliant Friend by Elena Ferrante, translated by Ann Goldstein (Europa Editions)

Blindly by Claudio Magris, translated by Anne Milano Appel (Yale University Press)

Walaschek’s Dream by Giovanni Orelli, translated by Jamie Richards (Dalkey Archive Press)

The post 2015 Italian Prose in Translation Award Shortlist appeared first on TRANSLATIONiSTA.

October 24, 2015

Translation on Tap in NYC, Nov. 1 – 15, 2015

It’s November again, which means it’s time for the New Literature from Europe Festival, which this year features two excellent-sounding translation events, listed below (or see the complete festival schedule here).

It’s November again, which means it’s time for the New Literature from Europe Festival, which this year features two excellent-sounding translation events, listed below (or see the complete festival schedule here).

Saturday, Nov. 7:

New Literature from Europe Translation Slam, featuring translators Mary Ann Newman and Mara Faye Lethem (Catalan), Sophie Duvernoy and Ross Benjamin (German), and Katrine Ø. Jensen and Kerri Pierce (Danish) facing off with their translations of Jordi Puntí, Bernhard Aichner, and Naja Marie Aidt. Moderated by Michael Reynolds. Ticketed event, more information here. Nuyorican Poets Café, 236 E. 3rd St., 7:00 p.m.

Sunday, Nov. 8:

Women in Translation (New Literature From Europe Festival): PEN Translation Committee Co-Chair Margaret S. Carson will be joined by NLE authors Naja Marie Aidt, Josefine Klougart, and Bettina Suleiman along with Three Percent’s Chad Post for a discussion of the gender gap in both international publishing and literature in translation. Free event, more information here. Bowery Poetry, 308 Bowery, 3:30 p.m.

Also Sunday, Nov. 8:

Trafika Europe presents an evening of Slovenian Literature featuring translator Tess Lewis reading her translations of Slovenian-Austrian author Maja Haderlap, joined by Slovenian poets Aleš Šteger and Tone Škrjanec and hosted by Andrew Singer. More information here. Bowery Poetry Club, 308 Bowery, 8:30 p.m.

Thursday, Nov. 12:

Stories from the Translation Lab: the translator/author pairs who’ve been working together at Writers Omi at Ledig House as part of the 2015 Translation Lab program will take the stage to discuss their collaborations. Featuring Christina MacSweeney, Daniel Saldana Paris, Alice Guthrie, Rasha Abbas, Izidora Angel, Hristo Karatoyanov, Amaia Gabantxo, and Miren Agur Meabe. More information here. Center for the Humanities, CUNY Graduate Center, 365 5th Avenue, Room C204, 6:30 p.m.

The post Translation on Tap in NYC, Nov. 1 – 15, 2015 appeared first on TRANSLATIONiSTA.

October 19, 2015

Who’s Getting Translated? Mostly Men

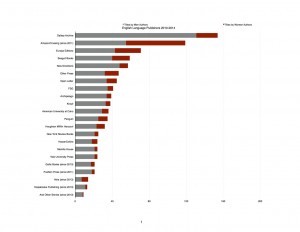

This past May, at a PEN World Voices panel entitled “Who We Talk About When We Talk About Translation: Women’s Voices,” PEN Translation Committee co-chair Margaret Carson, translator Alta Price and poet Jen Fitzgerald of VIDA presented a series of graphs showing the percentage of books by female authors published in 2014 by the top 25 publishers of translations into English. The results were disheartening. On closer examination, lots of wonderful publishing houses turn out to publish woefully few women. But these were the figures for only one year. Now the Women in Translation team has crunched and graphed the numbers (sourced from the Three Percent Database) for the years 2010-2014, and yes, the results are as we feared.

This past May, at a PEN World Voices panel entitled “Who We Talk About When We Talk About Translation: Women’s Voices,” PEN Translation Committee co-chair Margaret Carson, translator Alta Price and poet Jen Fitzgerald of VIDA presented a series of graphs showing the percentage of books by female authors published in 2014 by the top 25 publishers of translations into English. The results were disheartening. On closer examination, lots of wonderful publishing houses turn out to publish woefully few women. But these were the figures for only one year. Now the Women in Translation team has crunched and graphed the numbers (sourced from the Three Percent Database) for the years 2010-2014, and yes, the results are as we feared.

The single largest publisher of books translated into English is currently AmazonCrossing (119 titles published between 2011 – the year of its founding – and 2014), and it is also the single largest publisher of translated books written by women. These two facts are flip sides of the same coin: most of Amazon’s publishing is in genre fiction, including genres in which female authors predominate, giving Amazon a total translated list that is 54% female. Atria (an imprint of Simon & Schuster with a pretty commercial list) is next, with 50% women, and coming in at a distant third is Europa Editions (best known these days as the publisher of Elena Ferrante) with 39% women. And from this point on, the percentage of women on these lists drastically dwindles, such that some of my favorite publishing houses clock in with alarmingly low figures (New Directions, 16%; Archipelago, 13%). The longer the publisher’s list, the more indignant I am at the disparity. New Directions and Archipelago published 59 and 39 translated titles respectively during this five-year period, mostly by men; while Dalkey Archive (16%) was publishing three times as many translated titles: 154, of which only 23 were by women. The way I see it: the longer your list, the more times a year you’re making choices about whom to publish.

As has surely been said before, the more a publishing house focuses on work by older authors (e.g. New Directions’s emphasis on modernist writing, and NYRB’s [16% women] emphasis on classic works), the more likely their lists are to skew male, since the publishing world used to be even more inhospitable to women in centuries past than it is now. And publishing houses that focus on literature published in countries where the literary/publishing scene is still overwhelmingly male are most likely going to reflect that in their lists. But it’s definitely time now for publishers to be thinking actively about the ways in which their publishing programs contribute to an international literature that eclipses women’s voices. Surely we can be doing better than the 25% female authors published by these 25 presses (or 21% if you leave the commercially-oriented houses Amazon and Atria out of account). Why shouldn’t editors be especially on the lookout for interesting female authors to publish when the opportunity arises – even if the voices of these women are not the ones heard most loudly in their home countries and languages.

Meanwhile, big thanks to Margaret Carson and Alta Price for continuing to pursue this important project. You can follow their work on the Women in Translation Tumblr page, and if you’re going to the ALTA conference in Tucson later this month, check out the panel they’re running: “Where Are the Women in Translation?”

The post Who’s Getting Translated? Mostly Men appeared first on TRANSLATIONiSTA.

October 13, 2015

Amazon to Spend $10,000,000 on Translation

Image credit: Paul Sawers / VentureBeat

One of the things everyone seems to agree on where literary translation is concerned is that it’s not where the big bucks are, even though every few years we see a book in translation that becomes such a run-away bestseller that even a 0.5% royalty might really add up to something. (One recent such example was Hans Fallada’s Every Man Dies Alone – translated by Michael Hofmann – whose copies-sold figures ascended well into the six digits.) But the sales for many translated books never get as high as even five figures, so there generally isn’t much in the way of profit to spread around. But now the bookselling and (as of recently) publishing behemoth Amazon has decided that there’s profit to be made in Translationland, and they’re putting their money where their proverbial mouth is: $10 million of it, to be spent on translations to be published over the next five years. Sounds like good news. Whether it will prove to be an all-around boon for literary translators and the literature they love remains to be seen.

Which isn’t to say the news isn’t by and large good. Over the last few years, AmazonCrossing has become the number-one American publisher in terms of the number of translated titles published each year (and the representation of female authors). The majority of these titles are in various categories of genre fiction, which Amazon is singularly well-positioned to market and sell to readers who depend (in whole or in part) on its website for suggestions as to what to read next. Amazon does also publish works of “high” literary international fiction, in translations by well-respected translators such as Marian Schwartz, who translates Gelasimov for Amazon and Tolstoy for Yale. But the vast majority of its translation business is in the genre-fiction markets, and I assume that this is where the new venture will be centered.

Part of today’s announcement was the launch of a submissions portal that translators, foreign publishers, foreign authors, you name it can use to propose books to be included in this program. Most of the categories listed on the site are for genres (fantasy, thriller, mystery, etc.). And I assume that the majority of those who will be using this portal to suggest projects “over the transom” are people who have been unable to place their dream projects through conventional publishing outlets. And I suspect and fear that the translators who are hired in this way will be paid bottom-dollar for their work. After all, this is not a charitable venture; Amazon is running a business, and the point of a business like this is to be profitable, as I would assume AmazonCrossing has been thus far, given the volume of sales Amazon is is in a position to achieve. Several years ago, Amazon set up a portal that allowed translators to bid on translation projects to be published by AmazonCrossing, and while my contacts at Amazon assure me that these gigs do not automatically go to the lowest bidder (there’s someone checking credentials and weighing skill against cost), I don’t know what other purpose a bidding website can have other than to drive prices down, obviously at the translators’ expense. Drive them down to how low? It’s impossible to say, since last I heard Amazon was still requiring the translators who accepted contracts to work for it to sign a non-disclosure agreement. (If they’ve since dropped that requirement, I’d love to hear about it and will publish a statement to that effect right here.)

In the end, this new translation-project-suggestion-portal might wind up being just a way of creating a glorified form of self-publishing for translators and translation, the way an unpublished novelist can use print-on-demand to get her book at least nominally into print. Is this bad for the translation market? I’m going to go out on a limb and say that the proliferation of genre fiction in translation via AmazonCrossing hasn’t had any negative impact at all on the high-literature-translation world, and that the driving down of prices for the translation of genre fiction – while clearly not good for translators in general – has had few or no repercussions for translation rates elsewhere. As when negotiating with other publishers, professional translators will surely (or at least I hope so) refuse to sign contracts offering unacceptable terms. As for those not in a position to negotiate, they’re in no worse a position than the self-publishing authors, especially if (and this would be my strong recommendation to them) they make sure their contracts include a royalty clause so that if the crime novel or romance they translate happens to sell a hundred thousand copies, they’ll have a share in the windfall.

Meanwhile, good for Amazon for declaring Translationland a place where money can indeed be made. I’d like to see more major players in the mainstream publishing world taking note of that fact.

The post Amazon to Spend $10,000,000 on Translation appeared first on TRANSLATIONiSTA.

October 11, 2015

Apply Now for a 2016 PEN/Heim Translation Fund Grant

Allison Charette won a 2015 grant, photo ©Devon Rowland

Heads-up, translators, this year’s deadline for the receipt of PEN/Heim Translation Fund Grant applications is just over a month away: Nov. 16, 2015. So it’s definitely time to get cracking on those sample translations. I wrote so much about these grants and how to apply for them last year that I’m not going to repeat myself this time around. All you need to know is that these grants are one of the best ways out there for a up-and-coming translator and/or an up-and-coming project to get some attention from potential publishers (along with a little funding). So please read my write-up (including application tips), and the official instructions on the PEN website, and then get your applications in by Nov. 16!

The post Apply Now for a 2016 PEN/Heim Translation Fund Grant appeared first on TRANSLATIONiSTA.

October 10, 2015

Translation on Tap in NYC, Oct. 15 – 31, 2015

Quick, there’s still time to squeeze in some translation event-going before Halloween. Here’s what’s coming up:

Tuesday, Oct. 20:

Ferrante Fever: A Conversation about Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels, featuring her translator, Ann Goldstein, joined by Joan Acocella and Dayna Tortorici. More information here. McNally Jackson Books, 52 Prince St., 7:00 p.m.

Thursday, Oct. 22:

Launch event for Michel Houellebecq’s Submission featuring the book’s translator, Lorin Stein, joined by Eric Banks, Tom Bishop, and Adam Shatz. More information here. NYU’s Maison Française, 16 Washington Mews, 7:00 p.m.

Friday, Oct. 23:

Launch event for Emmanuel Bove’s A Raskolnikoff, with the book’s translator, Mitchell Abidor, joined by Donald Breckenridge. More information here. Unnamable Books: 600 Vanderbilt Ave, Brooklyn, 7:00 p.m.

Shelley Frisch and Catherine Porter

Thursday, Oct. 29:

The Bridge Series presents an evening on translating nonfiction (in this case: biographies and critical theory), with Shelley Frisch and Catherine Porter, moderated by Sal Robinson. More information here. McNally Jackson, 52 Prince St., 7:00 p.m.

The post Translation on Tap in NYC, Oct. 15 – 31, 2015 appeared first on TRANSLATIONiSTA.

Susan Bernofsky's Blog

- Susan Bernofsky's profile

- 62 followers