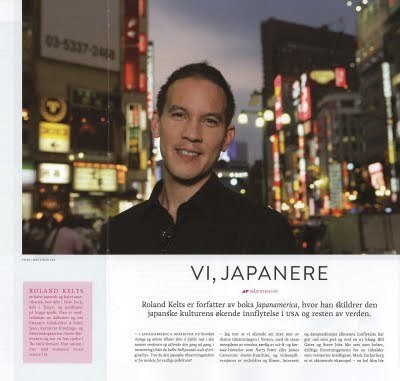

Roland Kelts's Blog, page 67

August 29, 2011

Latest Yomiuri column-on manga, sex and censorship

Imagine this: You're flying into Canada, bastion of peace and tolerance, and you're traveling light—a carry-on bag, a few magazines, a gift for your Canadian hosts; and your iPad, iPhone and laptop. Upon arrival, Canadian border officials suddenly seize and search the last of these. What they discover is not an explosive device or a cache of Al Qaeda contacts, but rather an item they deem incendiary nonetheless: a stash of digital manga images, some featuring doujinshi (fan-made) illustrations, others that might be labeled lolicon (lolita complex) manga, showing eroticized renderings of what might be underage characters. Whatever the designation, they are all digital images saved on your personal laptop, and they are all imaginary.

An American computer programmer in his mid-20s went through this humiliation last year while visiting a friend in Canada. He has since been charged with possession and importation of child pornography, and he faces a minimum of one year in prison if convicted—not to mention a ruined reputation for a lifetime. I have written before in this column about the growing intolerance of manga and anime on both sides of the Pacific. Last year, 39 year-old American Christopher Handley was convicted of possessing child pornography in Iowa after US postal officials opened parcels of lolicon manga he had ordered from Japan. Shortly thereafter, Tokyo Gov. Shintaro Ishihara rammed through the now notorious bill 156, legislating the morality of socially disruptive manga imagery while ignoring the propagation of live-action child pornography.

But the Canadian case takes intolerance into the digital age. Manga is a distinctly Japanese art form, with its own set of conventions cultivated over decades, if not centuries—especially if one traces its origins to Edo-era ukiyo-e woodblock prints, whose most famous practitioner, Katsuhika Hokusai, actually coined the term. Artists often thrive on the borders, the distinctions between what's allowable and what risks censure, in order to reveal or convey truths. Hokusai's graphically sensual "The Dream of the Fisherman's Wife," depicting a young woman being pleasured by octopi, is often cited as an example of the libertarian aesthetic eroticism spanning the centuries between woodblock prints and erotic manga.

What happens when authorities with no experience with Japanese art forms, contemporary or ancient, encounter digital graphics devoid of even a publisher's most basic print disclaimers and formalities?

"There's insufficient training of government officials in the US and Canada as to the artistic merit of manga," says Charles Brownstein, the executive director of the New York-based Comic Book Legal Defense Fund (CBLDF), the oldest and most well-established organization devoted to defending the rights of comics enthusiasts and basic freedoms of expression.

"We've seen a recent spike in manga cases, but this [Canada] case is the most egregious—someone who was not only stopped, searched and harassed, but instead of simply having material seized, he was actually prosecuted for importation of what is alleged to be child pornography for manga images that were stored on his computer."

The Canada case embodies a perfect storm of misreadings: Western officials who don't understand Japanese aesthetics are arresting a Western fan of Japanese art via a medium, digital storage, that is even further divorced from culture and context.

"There is no understanding that one can have an appreciation of a different set of artistic traditions with a different set of taboos, without being a threat to the community," adds Brownstein. "A lot of people are at risk who don't know they're at risk right now. The courts simply haven't caught up with culture. One can appreciate the art without participating in the crime depicted."

The CBLDF is currently raising funds to defend the American manga fan in Canadian courts next month. When I spoke with Brownstein in New York, he was $30,000 from his goal of defending our imaginations from imaginary crimes.

My latest Daily Yomiuri column-on manga and sex

Imagine this: You're flying into Canada, bastion of peace and tolerance, and you're traveling light—a carry-on bag, a few magazines, a gift for your Canadian hosts; and your iPad, iPhone and laptop. Upon arrival, Canadian border officials suddenly seize and search the last of these. What they discover is not an explosive device or a cache of Al Qaeda contacts, but rather an item they deem incendiary nonetheless: a stash of digital manga images, some featuring doujinshi (fan-made) illustrations, others that might be labeled lolicon (lolita complex) manga, showing eroticized renderings of what might be underage characters. Whatever the designation, they are all digital images saved on your personal laptop, and they are all imaginary.

An American computer programmer in his mid-20s went through this humiliation last year while visiting a friend in Canada. He has since been charged with possession and importation of child pornography, and he faces a minimum of one year in prison if convicted—not to mention a ruined reputation for a lifetime.

I have written before in this column about the growing intolerance of manga and anime on both sides of the Pacific. Last year, 39 year-old American Christopher Handley was convicted of possessing child pornography in Iowa after US postal officials opened parcels of lolicon manga he had ordered from Japan. Shortly thereafter, Tokyo Gov. Shintaro Ishihara rammed through the now notorious bill 156, legislating the morality of socially disruptive manga imagery while ignoring the propagation of live-action child pornography.

But the Canadian case takes intolerance into the digital age. Manga is a distinctly Japanese art form, with its own set of conventions cultivated over decades, if not centuries—especially if one traces its origins to Edo-era ukiyo-e woodblock prints, whose most famous practitioner, Katsuhika Hokusai, actually coined the term. Artists often thrive on the borders, the distinctions between what's allowable and what risks censure, in order to reveal or convey truths. Hokusai's graphically sensual "The Dream of the Fisherman's Wife," depicting a young woman being pleasured by octopi, is often cited as an example of the libertarian aesthetic eroticism spanning the centuries between woodblock prints and erotic manga.

What happens when authorities with no experience with Japanese art forms, contemporary or ancient, encounter digital graphics devoid of even a publisher's most basic print disclaimers and formalities?

"There's insufficient training of government officials in the US and Canada as to the artistic merit of manga," says Charles Brownstein, the executive director of the New York-based Comic Book Legal Defense Fund (CBLDF), the oldest and most well-established organization devoted to defending the rights of comics enthusiasts and basic freedoms of expression.

"We've seen a recent spike in manga cases, but this [Canada] case is the most egregious—someone who was not only stopped, searched and harassed, but instead of simply having material seized, he was actually prosecuted for importation of what is alleged to be child pornography for manga images that were stored on his computer."

The Canada case embodies a perfect storm of misreadings: Western officials who don't understand Japanese aesthetics are arresting a Western fan of Japanese art via a medium, digital storage, that is even further divorced from culture and context.

"There is no understanding that one can have an appreciation of a different set of artistic traditions with a different set of taboos, without being a threat to the community," adds Brownstein. "A lot of people are at risk who don't know they're at risk right now. The courts simply haven't caught up with culture. One can appreciate the art without participating in the crime depicted."

The CBLDF is currently raising funds to defend the American manga fan in Canadian courts next month. When I spoke with Brownstein in New York, he was $30,000 from his goal of defending our imaginations from imaginary crimes.

Manga sex sensation!

Manga's cultural conflict

Imagine this: You're flying into Canada, bastion of tolerance and peacability, and you're traveling light—a carry-on bag, a magazine or three, a gift for your Canadian hosts, and your iPad, iPhone and laptop. Upon arrival, Canadian border officials suddenly seize and search the last of these. What they discover is not an explosive device or a cache of Al Qaeda contacts, but an item they nonetheless deem incendiary: a stash of digital manga images, some featuring doujinshi (or 'fan-made') illustrations, others that might be labeled lolicon ('Lolita complex') manga, showing what may be eroticized renderings of what might be underage characters. Whatever the designation, they are all digital images saved on your personal laptop, and they are all imaginary.

An American computer programmer in his mid-20s went through this humiliation last year while visiting a friend in Canada. He has since been charged with the possession and importation of child pornography, and he faces a minimum of one year in prison if convicted—not to mention a lifetime's reputation ruined.

I have written about the growing intolerance of manga and anime on both sides of the Pacific in this column. Last year, 39 year-old American Christopher Handley was convicted of possessing child pornography in Iowa after US postal officials opened parcels of lolicon manga he had ordered from Japan. Shortly thereafter, Tokyo Gov. Shintaro Ishihara rammed through the now notorious bill 156, legislating the morality of socially disruptive manga imagery while ignoring the propagation of live-action child pornography.

But the Canadian case takes intolerance into the digital age. Manga is a distinctly Japanese art form, with its own set of conventions cultivated over decades, if not centuries—especially if one traces its origins to Edo-era woodblock prints (ukiyo-e), whose most famous practitioner, Katsuhiko Hokusai, actually coined the term. Artists often thrive on the borders, the distinctions between what's allowable and what risks censure, in order to reveal or convey truths. Hokusai's graphically sensual "The Dream of the Fisherman's Wife," depicting a young woman being pleasured by octopi, is often cited as an example of the libertarian aesthetic eroticism spanning the centuries between woodblock prints and erotic manga.

What happens when authorities with no experience with Japanese art forms, contemporary or ancient, encounter digital graphics devoid of even a publisher's most basic print disclaimers and formalities?

"There's insufficient training of government officials in the US and Canada as to the artistic merit of manga," says Charles Brownstein, the executive director of the New York-based Comic Book Legal Defense Fund (CBLDF), the oldest and most well-established organization devoted to defending the rights of comics enthusiasts and basic freedoms of expression.

"We've seen a recent spike in manga cases, but this [Canada] case is the most egregious—someone who was not only stopped, searched and harassed, but instead of simply having material seized, he was actually prosecuted for importation of what is alleged to be child pornography for manga images that were stored on his computer."

In other words: the Canada case embodies a perfect storm: Western officials who don't understand Japanese aesthetics are arresting a Western fan of Japanese art via a medium, digital storage, that is even further divorced from culture and context.

"There is no understanding that one can have an appreciation of a different set of artistic traditions with a different set of taboos, without being a threat to the community," adds Brownstein. "A lot of people are at risk who don't know they're at risk right now. The courts simply haven't caught up with culture. One can appreciate the art without participating in the crime depicted."

The CBLDF is currently raising funds to defend the American manga fan in Canadian courts next month. At the time I spoke to Brownstein in New York, he was $30,000 from his goal of defending our imaginations from imaginary crimes. We have to pay cash to preserve our freedoms. Imagine that.

Post-Irene, Soho, my hood

August 23, 2011

quakes in two cities

All's well, but it certainly didn't feel well. I've felt far worse in Tokyo, but something about being in NYC, where no one knew what was going on (everyone scattering into the street below, shouting into their cell phones--by far the worst thing you can do during a quake), and there are no established alert or emergency systems, and so many of the buildings, down here, especially, are already old and crumbling and made of stiff brick that will collapse instead of 'sway'...no, it didn't feel well at all.

When I first realized it wasn't another 18-wheeler grinding cobblestones in Soho, that the movement was both harder and more sustained, my little mind ticker registered 'earthquake,' and I was actually annoyed. I think I spoke to myself, muttering like a geezer, saying something like, "What? Oh, come on! Here?"

By the time I had risen from my desk, glanced at the table vase to confirm that, yes, the liquid was indeed sloshing from side to side, and begun my crouch beneath the mahogany, it had stopped. I looked around, stood and went to a window. Seemed like everyone was out on the corner--the deli staffers, the neighbors, tourists, local shopkeepers--aglow in bright sunlight and looking anxiously up and around at the buildings.

August 21, 2011

Japanamerica lands in Latin America

August 18, 2011

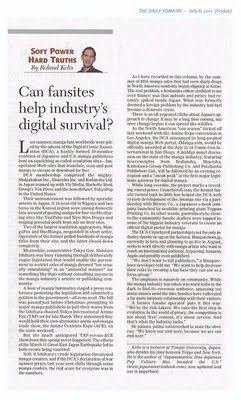

JManga.com launches on schedule

The first 100% legitimate publisher- and industry-backed English-language portal for digital manga is now up and open (JManga.com), developed in collaboration with the folks at Crunchyroll.com--the former fansite that went legal in 2008. I wrote about such industry-fandom tie-ups in one of my recent columns for the Yomiuri.

The first 100% legitimate publisher- and industry-backed English-language portal for digital manga is now up and open (JManga.com), developed in collaboration with the folks at Crunchyroll.com--the former fansite that went legal in 2008. I wrote about such industry-fandom tie-ups in one of my recent columns for the Yomiuri.

August 16, 2011

Japanamerica a top-5 book on Japan

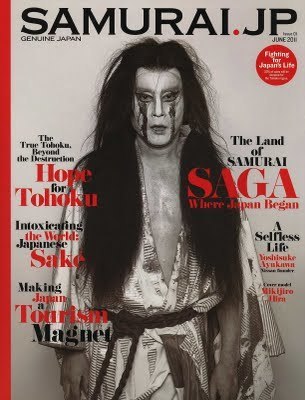

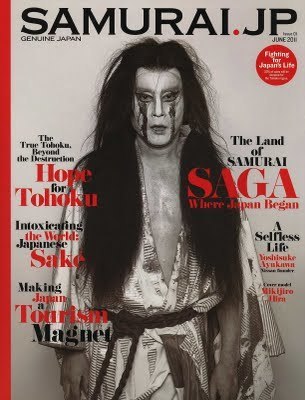

Japanamerica in Samurai.JP, new mag

August 15, 2011

Japanamerica lands in Norway