Roland Kelts's Blog, page 64

November 8, 2011

JAPANAMERICA (the book) is 'Deal of the Day' @Crunchyroll

The fine folks at Crunchyroll.com are offering freshly pubbed copies of , the book, as their "Daily Deal" for November 8, 2011. Drop by and pick it up for pennies, yen or euro, while supplies and hours last. Violence-free looting op .

Published on November 08, 2011 06:04

November 7, 2011

Gigging in Tokyo, 2011

Published on November 07, 2011 04:20

November 3, 2011

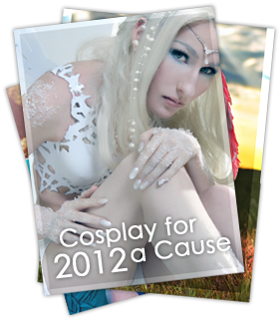

Cosplay in the USA--Yomiuri column

SOFT POWER HARD TRUTHS / American anime fans show that cosplay is the sincerest form of flattery

Roland Kelts / Special to The Daily Yomiuri

An estimated 105,000 fans attended last month's combined New York Anime Festival and Comic Con--and you couldn't walk a meter on the

convention floor without seeing or literally bumping into someone in

costume.

The larger North American anime conventions feature artists and

voice actors from Japan and the United States as celebrity guests,

screenings, panels and live performances alongside booths offering

merchandise and promotional paraphernalia.

But cosplay, an import from Japan that involves wearing, and often

posing provocatively in, a homemade costume of your favorite character,

may be the biggest draw.

"It's like total escape," a teenager from Philadelphia said as he

adjusted the collar of his costume, based on a character from Hetalia:

Axis Powers, a notably popular title this year. "You can't do this every

day. And it's really addictive."

The appeal of cosplay outside Japan is a perfect example of the

transcultural boomerangs that characterize much of contemporary popular

culture. As Japanese otaku of an older generation will tell you,

cosplay, and the devotional fandom behind it, came from the United

States: Photos of costumed fans at North American sci-fi conventions,

such as those revolving around Star Trek, appeared in magazines imported

to Japan in the 1960s and '70s.

Japanese readers adopted the practice, using characters from their

homegrown anime and manga series. As the popularity of manga and anime

spiked outside Japan, fast-evolving Internet access provided overseas

fans first with a peephole and then a massive window onto what looked

like an enticing made-in-Japan phenomenon. The word itself, cosplay, is a

giddy transcultural mashup of the English "costume" and "play."

"Cosplay [is now] a more accepted hobby in North America than in

Japan," noted Riddle Lee, an Atlanta-based costume designer and model

who has been cosplaying for 12 years. Lee cited the variety of genres

beyond anime and manga--comics, movies and the sci-fi subgenre

steampunk--that have become a part of the cosplay scene in the United

States.

"It allows more ethnicities and age ranges to be involved. But those

who are cosplaying from anime and Japan-based videogames really do have

a sincere interest in Japan."

Photographer Ejen Chuang agrees. In 2009, Chuang crisscrossed the

United States, attending six anime conventions to shoot over 1,650

cosplayers, 250 of whom appear in his colorful and hefty coffee-table

tome,

"Many cosplayers I've talked to and photographed have since moved to

Japan, either for studies or jobs," he said. "They wouldn't put so much

effort into their outfits if they did not respect the original source."

For some, cosplay has become serious stuff. "The skills

involved--sculpting, styling, sewing, makeup--could help get you a

career in fashion or film," Lee said.

She has turned her own skill set toward charity. In the wake of the

March 11 tsunami and earthquake, Lee launched "Cosplay for a Cause," a

nonprofit organization whose mission is to raise money for disaster

relief. She contacted artists and fellow cosplayers worldwide to create a

glossy 2012 calendar, with all proceeds going directly to the Japanese

Red Cross Society.

"Japan has been such an influence on my life," she explains, "from

video games to anime characters to food and even its rich history, which

fascinates me."

A New Jersey-based cosplayer known by the moniker Yuffiebunny told

me that her passion has led to her own business, Head Kandi, creating

hand- and custom-made costume headpieces, wigs and other hair

enhancements. She also judges cosplay contests, models for Web sites and

magazines, sometimes gets hired as a cosplayer for events--and, of

course, attends anime conventions regularly.

While cosplaying is not a career for her, she says, "It's definitely not a sideline or part-time gig. I work very hard at it."

Yaya Han, also from Atlanta, and Chicago-based Barbara Staples both

tell me that cosplaying and its related activities (designing costumes

and accessories on commission, modeling, public speaking and attending

conventions) have taken over their lives full-time.

Han said American cosplayers are not only diverse in age, gender and

ethnicity, but also in levels of devotion. She divides participants

into three groups: The super amateurs, who "know nothing about proper

sewing techniques, props, wigs, et cetera"; the Halloween types, out for

"occasional fun"; and the true devotees, members of the "cosplay

community [who] make cosplay a lifestyle."

Staples, 29, attended her first anime convention 14 years ago, and

like many women of her generation, was lured by the watershed shojo

anime series Sailor Moon. She now runs her own costume design business,

Lemonbrat, employing six staffers and two interns.

"I feel like I'm working two full-time jobs," she said, "because it takes up so much time."

Americans who cosplay have skewed both younger and older in recent

years, with teens now sporting anime and manga costumes alongside

cosplayers going gray or even fluffy white. They are drawn to the spirit

of interactivity, role-playing participation and community, plus a dose

of sincere passion--all emanating from a pop culture universe thousands

of miles away.

Staples didn't cosplay at her first convention. "I didn't realize

people dressed up," she told me. "Then I noticed and thought, 'I can

make better costumes than that.' Cosplay was right on the cusp of

becoming really popular."

===

Kelts is a visiting scholar at the University of Tokyo who divides

his time between Tokyo and New York. He is the author of

[ @Yomiuri here ]

Roland Kelts / Special to The Daily Yomiuri

An estimated 105,000 fans attended last month's combined New York Anime Festival and Comic Con--and you couldn't walk a meter on the

convention floor without seeing or literally bumping into someone in

costume.

The larger North American anime conventions feature artists and

voice actors from Japan and the United States as celebrity guests,

screenings, panels and live performances alongside booths offering

merchandise and promotional paraphernalia.

But cosplay, an import from Japan that involves wearing, and often

posing provocatively in, a homemade costume of your favorite character,

may be the biggest draw.

"It's like total escape," a teenager from Philadelphia said as he

adjusted the collar of his costume, based on a character from Hetalia:

Axis Powers, a notably popular title this year. "You can't do this every

day. And it's really addictive."

The appeal of cosplay outside Japan is a perfect example of the

transcultural boomerangs that characterize much of contemporary popular

culture. As Japanese otaku of an older generation will tell you,

cosplay, and the devotional fandom behind it, came from the United

States: Photos of costumed fans at North American sci-fi conventions,

such as those revolving around Star Trek, appeared in magazines imported

to Japan in the 1960s and '70s.

Japanese readers adopted the practice, using characters from their

homegrown anime and manga series. As the popularity of manga and anime

spiked outside Japan, fast-evolving Internet access provided overseas

fans first with a peephole and then a massive window onto what looked

like an enticing made-in-Japan phenomenon. The word itself, cosplay, is a

giddy transcultural mashup of the English "costume" and "play."

"Cosplay [is now] a more accepted hobby in North America than in

Japan," noted Riddle Lee, an Atlanta-based costume designer and model

who has been cosplaying for 12 years. Lee cited the variety of genres

beyond anime and manga--comics, movies and the sci-fi subgenre

steampunk--that have become a part of the cosplay scene in the United

States.

"It allows more ethnicities and age ranges to be involved. But those

who are cosplaying from anime and Japan-based videogames really do have

a sincere interest in Japan."

Photographer Ejen Chuang agrees. In 2009, Chuang crisscrossed the

United States, attending six anime conventions to shoot over 1,650

cosplayers, 250 of whom appear in his colorful and hefty coffee-table

tome,

"Many cosplayers I've talked to and photographed have since moved to

Japan, either for studies or jobs," he said. "They wouldn't put so much

effort into their outfits if they did not respect the original source."

For some, cosplay has become serious stuff. "The skills

involved--sculpting, styling, sewing, makeup--could help get you a

career in fashion or film," Lee said.

She has turned her own skill set toward charity. In the wake of the

March 11 tsunami and earthquake, Lee launched "Cosplay for a Cause," a

nonprofit organization whose mission is to raise money for disaster

relief. She contacted artists and fellow cosplayers worldwide to create a

glossy 2012 calendar, with all proceeds going directly to the Japanese

Red Cross Society.

"Japan has been such an influence on my life," she explains, "from

video games to anime characters to food and even its rich history, which

fascinates me."

A New Jersey-based cosplayer known by the moniker Yuffiebunny told

me that her passion has led to her own business, Head Kandi, creating

hand- and custom-made costume headpieces, wigs and other hair

enhancements. She also judges cosplay contests, models for Web sites and

magazines, sometimes gets hired as a cosplayer for events--and, of

course, attends anime conventions regularly.

While cosplaying is not a career for her, she says, "It's definitely not a sideline or part-time gig. I work very hard at it."

Yaya Han, also from Atlanta, and Chicago-based Barbara Staples both

tell me that cosplaying and its related activities (designing costumes

and accessories on commission, modeling, public speaking and attending

conventions) have taken over their lives full-time.

Han said American cosplayers are not only diverse in age, gender and

ethnicity, but also in levels of devotion. She divides participants

into three groups: The super amateurs, who "know nothing about proper

sewing techniques, props, wigs, et cetera"; the Halloween types, out for

"occasional fun"; and the true devotees, members of the "cosplay

community [who] make cosplay a lifestyle."

Staples, 29, attended her first anime convention 14 years ago, and

like many women of her generation, was lured by the watershed shojo

anime series Sailor Moon. She now runs her own costume design business,

Lemonbrat, employing six staffers and two interns.

"I feel like I'm working two full-time jobs," she said, "because it takes up so much time."

Americans who cosplay have skewed both younger and older in recent

years, with teens now sporting anime and manga costumes alongside

cosplayers going gray or even fluffy white. They are drawn to the spirit

of interactivity, role-playing participation and community, plus a dose

of sincere passion--all emanating from a pop culture universe thousands

of miles away.

Staples didn't cosplay at her first convention. "I didn't realize

people dressed up," she told me. "Then I noticed and thought, 'I can

make better costumes than that.' Cosplay was right on the cusp of

becoming really popular."

===

Kelts is a visiting scholar at the University of Tokyo who divides

his time between Tokyo and New York. He is the author of

[ @Yomiuri here ]

Published on November 03, 2011 20:51

November 1, 2011

Christmas in Japan starts now

Published on November 01, 2011 08:10

October 26, 2011

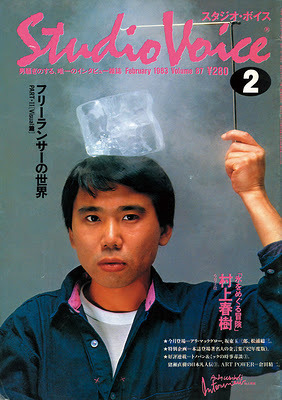

More on Murakami & 1Q84 for NPR

More expansive talk about Haruki's reputation in Japan and 1Q84 with dear friend Madeleine Brand for The Madeleine Brand Show on KPCC, the NPR affiliate in Los Angeles. Audio

here

.

Extra: Cover of the now-defunct Studio Voice magazine featuring Haruki in the auspicious preceding year of 1Q83 (courtesy of Giant Robot ):

Extra: Cover of the now-defunct Studio Voice magazine featuring Haruki in the auspicious preceding year of 1Q83 (courtesy of Giant Robot ):

Published on October 26, 2011 05:47

October 20, 2011

**updated: Talk in Tokyo, Oct. 2011

[Sudo, McDonald, Kelts]

Manga and Anime, Japan's Most Important, but Hidden Industries

Time: 2011 Oct 27 12:00 - 14:00

Summary:

Professional Luncheon

Tadashi Sudo, CEO of AnimeAnime.jp

Roland Kelts, Japanese pop-culture Expert & Author of "Japanamerica."

Christopher Macdonald, CEO& Publisher, Anime News Network

Description:

Japanese pop culture is on a tear worldwide. Manga and anime, long

popular at home and abroad, are becoming an important export business,

with even METI and MOFA throwing their support behind the genres.

Universities are setting up study courses and archiving collections,

while even the sober British Museum staged a manga exhibition recently.

But, once again, an industry that Japan created and developed is

increasingly under threat, in particular from the content industries of

South Korea and China. In addition, Internet distribution provides a

huge audience - but one that is disinclined to pay for content, stunting

the Japanese firms that produce it. What is the current situation

surrounding one of modern Japan's most important -- but hidden --

industries? And what is its future?

The panelists include Tadashi Sudo, the CEO of AnimeAnime.jp; Roland

Kelts, an expert on Japanese pop-culture and the author of the book

"Japanamerica"; and Christopher Macdonald, the CEO & Publisher of

Anime News Network.

Published on October 20, 2011 22:29

**updated: Talk in Tokyo Thursday, 10/27

[more info here: @FCCJ ]

Manga and Anime, Japan's Most Important, but Hidden Industries

Time: 2011 Oct 27 12:00 - 14:00

Summary:

Professional Luncheon

Tadashi Sudo, CEO of AnimeAnime.jp

Roland Kelts, Japanese pop-culture Expert & Author of "Japanamerica."

Christopher Macdonald, CEO& Publisher, Anime News Network

Language:

The speech and Q & A will be in English.

Description:

Japanese manga and anime take on the world!

Japanese pop culture is on a tear worldwide. Manga and anime, long

popular at home and abroad, are becoming an important export business,

with even METI and MOFA throwing their support behind the genres.

Universities are setting up study courses and archiving collections,

while even the sober British Museum staged a manga exhibition recently.

But, once again, an industry that Japan created and developed is

increasingly under threat, in particular from the content industries of

South Korea and China. In addition, Internet distribution provides a

huge audience - but one that is disinclined to pay for content, stunting

the Japanese firms that produce it. What is the current situation

surrounding one of modern Japan's most important -- but hidden --

industries? And what is its future?

The panelists include Tadashi Sudo, the CEO of AnimeAnime.jp; Roland

Kelts, an expert on Japanese pop-culture and the author of the book

"Japanamerica"; and Christopher Macdonald, the CEO & Publisher of

Anime News Network.

Please join us for a fascinating look inside the business of manga

and anime -- and a lens into one of Japan's most creative areas of art

and expression.

Menu: Herb Marinated Sauteed Swordfish with Tomato & Olive Sauce, Carrots and Green Vegetables

Please reserve in advance, still & TV cameras inclusive. The charge for members/non-members is 1,700/2,600 yen, non-members eligible to attend may pay in cash. Reservations canceled less than one hour in advance for working press members, and 24 hours for all others, will be charged in full. Reservations and cancellations are not complete without confirmation.

Professional Activities Committee

Published on October 20, 2011 22:29

Talk in Tokyo next Thursday, 10/27

[more info here: @FCCJ ]

Manga and Anime, Japan's Most Important, but Hidden Industries

Time: 2011 Oct 27 12:00 - 14:00

Summary:

Professional Luncheon

Tadashi Sudo, CEO of AnimeAnime.jp

Roland Kelts, Japanese pop-culture Expert & Author of "Japanamerica."

Christopher Macdonald, CEO& Publisher, Anime News Network

Language:

The speech and Q & A will be in English.

Description:

The full text of this notice and menu will be posted shortly.

Please reserve in advance, still & TV cameras inclusive. The charge for members/non-members is 1,700/2,600 yen, non-members eligible to attend may pay in cash. Reservations canceled less than one hour in advance for working press members, and 24 hours for all others, will be charged in full. Reservations and cancellations are not complete without confirmation.

Professional Activities Committee

Published on October 20, 2011 22:29

BBC interview on Haruki Murakami & 1Q84

My chat this week with the very sporting Anna McNamee about Haruki Murakami, historical amnesia and Alice in Wonderland on the eve of the release of 1Q84, Books 1 & 2, in the UK. Book 3 in the UK and the single-volume US edition are due out Monday, October 25.

Audio is here.

Audio is here.

Published on October 20, 2011 16:40

New England

Traveling to New England

I have lived in cities as disparate and different as Tokyo,

New York, Osaka, London, San Francisco and Anchorage, Alaska. From each city I traveled regionally,

exploring Asia from Japan, Europe from England, the native villages of St.

Lawrence Island from Anchorage, and so on. I have repeated some of those journeys later

in life, but most of them I have taken only once. While I'd love to return to Savoonga, Alaska,

for example, a Yupik village of 600 or so in the Bering Sea, I'm not sure if or

when I'll have time to do so before I die.

My most frequent destination, however, has been the

six-state northeastern region of the United States known as New England. Aside from my birth and a few early years

spent in New York, and one term attending kindergarten in Morioka, my Japanese

grandparents' home, the bulk of my childhood happened in New England.

Like much of the US, New England is largely rural, 'inaka,' hemmed in by minor mountains to

the West, and to the East, the North Atlantic.

I grew up in towns near large grass fields rife with insects and muddy trails,

silent chilly brown sands and dull family restaurants. My parents were never rich, but they spent

and saved wisely, and they gave me a childhood largely bereft of conflict. I spent a lot of time outdoors in safe

natural environs.

Two towns became my destinations after I left home for

college and for good at age 18: Exeter, New Hampshire and Andover, Massachusetts—small,

locally historical communities that boast two of America's most famous private

schools: Phillips Exeter Academy and Phillips Andover Academy, respectively. While I attended Exeter for brief periods as a

student, and taught there for stretches as a young adult, neither institution

had a claim on my family's residency. My

parents just happened to choose the towns as safe and secure havens for

convenient commutes and stable child-rearing.

When I attended college in Ohio, an exotically flat and

earnest place for me at the time, my awareness of New England became equally

exotic. I began for the first time to

see my childhood home as a distinctive place.

The classmates I got to know at Oberlin were from other parts of the US

and the world. They commented upon my

accent (an 'r-less' New England dialect), my worldviews (provincial), and my

tastes in clothing and food. At Oberlin,

many students were card-carrying hippies or hipsters, wearing tattered blue

jeans and accelerating their used Volvos with bare feet. I wore dinner jackets, a beret, and a heavy

dark Pea Coat in the winter. For me,

England and Europe were the models of fashion—not the laid-back US West Coast—a

stance I'd inherited from New England, though I didn't know it then.

For college, my father drove me from New Hampshire to

Ohio. One of my Korean-American

classmates packed him a lunch and several cans of Pepsi for his solo trip

home. When I saw him off, I felt the

first sting of a loss and separation that would gradually pierce and infect my

life. But I didn't know that then. I just knew that I'd be traveling back to New

England for the winter holidays. I'd see him soon.

Since then, the track back to New England has taken

different forms. I remember catching

Amtrak trains from Cleveland to Boston amid snowstorms and multiple delays,

alighting in Boston to see my father on the platform, graying and

wide-eyed. Sometimes I flew (how I had the

money, I have no idea). On one takeoff, the shuddering plane returned to the

runway in Cleveland with an oil leak. A

renowned African-American Oberlin professor sat next to me and grabbed my hand

as we chugged through the air, jerkily, then landed smoothly, fire trucks

swarming. I was scared but eerily calm.

Potential tragedy, when you're in your teens, is a kind of entertaining

normalcy. What I learned then was that

the same concept for an older man smells of death.

I moved to California right after graduation. Things went downhill—I ran out of money in

Berkeley, felt alienated in San Francisco, and got held-up at gunpoint by

drug-runners in Oakland. I returned to

New England by air near Christmas, landing amid a snowstorm.

I returned to my parents' home in New Hampshire, told them

nothing of my travails, and went for a walk with the family dog, a Welsh terrier,

in a nearby parking lot. I held him close

to me as we watched the flakes fall. It

was balm.

Thereafter I moved to New York and graduate school at

Columbia. Traveling to New England

became easier, but no less complicated. I

took Amtrak trains from New York's Penn Station to Boston's South Station,

eyeing my reflection in the window as we passed maples and pines and choppy

harbors in Connecticut, the longest state en route. I felt a mixture of regret and glamour—a

newly minted New Yorker still entrapped by his roots in the leafy suburbs up north,

no wiser, no richer, but with a Manhattan zip code on his mail. Surely that was

worth something?

When I opted for a year in Japan in 1998, I was making a

break from my life's continuum. Again, I

had no idea at the time. I moved to

Osaka to write a story on commission, meaning I'd get paid. I considered myself a proverbial New Yorker,

and was worried that Japanese cities would be too conservative and too

inconvenient for my habits.

Osaka, and later, Tokyo, would prove me embarrassingly

wrong, of course. To this day, nowhere

I've been or lived is more urban or convenient than a Japanese city. Forget New York's claim to be the city that

never sleeps: Japanese cities are simply always awake.

Still, whether I'm flying to Bangkok, Kuala Lumpur, Brisbane

or Paris, the trek to New England remains my traveler's cornerstone. Now it involves a 4-hour road-trip or 5-hour

train ride from New York (as domestic flights have become more expensive and

less convenient), a 14-hour flight from Tokyo, or a hop-skip-jump itinerary

from Sydney to Los Angeles, New York and Boston—and now an additional train or

bus ride to a tiny town called Ballardvale, which is close enough to my

drive-wary retiree parents' house in Andover.

Wherever I am, I travel back to New England, its looming

pines and dusky sands containing the memories, and the now aged man and woman, my

parents, that will be the closest I will ever get to home.

Published on October 20, 2011 00:55