Angela Ackerman's Blog: Writers Helping Writers, page 67

March 23, 2021

What Is Your Character’s Emotional Shielding and Why Does It Matter?

In the real world, we���re all products of our pasts. Good and bad, the people, events, and situations we���ve encountered have influenced us in profound ways, impacting our morals and beliefs, our day-to-day habits, our personal preferences, even our personality traits. This should be as true for our characters as it is for us.

As we dig through our characters��� backstories, we quickly come to find that the most formative element is the emotional wound���a terrible past experience that was so debilitating they���ll do anything to avoid going through it again. Wounding events are particularly insidious because the harm they cause isn���t limited to the event itself; it���s often the first of many toppling dominoes that alter the character in alarming ways, molding her into who she���ll be at the start of your story.

Her wound, and the emotional shielding that follows, will contribute to her personality, beliefs and morals, story goals, and more. It���s important to understand those aftereffects and what they���ll mean for your character so you can write her in an authentic and consistent way that will resonate with readers.

What is Emotional Shielding?

The aftermath of a wounding event is a chaotic time full of questions with no easy answers. How did this happen? Why me? And the most critical one: How do I make sure it doesn���t happen again? Out of a desperate need to safeguard herself from further pain, the character knowingly or subconsciously deploys her emotional shielding���protections meant to keep her safe. These are universal to the human experience and come in a number of forms that can be applied to your character after a traumatic experience.

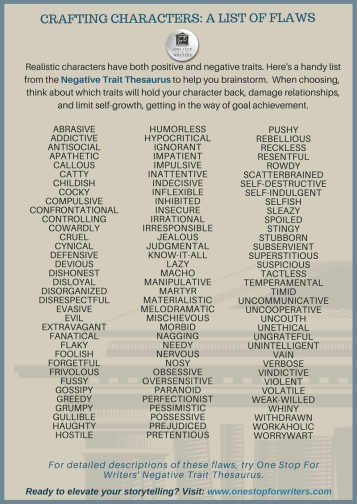

Flaws

(Click image to download)

Many times, a character will seek to keep trauma from recurring by adopting new traits that she believes will make her stronger or more impervious to harm. A woman who has escaped domestic abuse may think that the key to avoiding further mistreatment is in controlling every part of her life���and maybe the lives of those around her. The teenager who told the truth about a crime but wasn���t believed may become apathetic. An employee whose work was stolen by his boss could easily become uncooperative, believing that keeping his ideas to himself is the best way to protect them.

On the surface, these new traits seem to be a good way to ward off danger. In reality, they cause ancillary problems that make it difficult for the characters to succeed in many areas of life.

Dysfunctional BehaviorsWhen flaws are adopted, new behaviors inevitably follow. The abuse survivor who needs to now control everything may become hypercritical, making impossible demands of herself and those in her charge. The apathetic boy might withdraw emotionally from others. Our uncooperative businessman could hold back at the office, not contributing in meetings or team projects and thereby sabotaging his success at work. The habits that grow out of a character���s flaws are typically damaging, destroying relationships and making it difficult for them to achieve story goals.

False BeliefsWhen trauma occurs, one of the first things we do is examine what happened, mentally replaying it to see how it could have been avoided. We want to identify who was at fault so we know who to blame and where to direct our negative emotions. Very often, we end up pointing the finger at ourselves. If I hadn���t been so self-involved, I would���ve seen the warning signs; if I���d been more obedient, my parents wouldn���t have divorced.

The lies that result lead to a form of self-blame or the belief that had the character been more worthy, chosen differently, trusted someone else, paid more attention, safeguarded herself, etc., a different outcome would have resulted. Lies like these undermine the character���s confidence, making it virtually impossible for her to reach her dreams and find fullness and contentment.

BiasesIn some cases, the victim of a trauma may find blame elsewhere: the government, a corporation, God, ���those people.��� When this happens, it���s easy for a wider sense of disillusionment to take shape in the form of biases. The abuse victim may come to believe that all men are violent. The teen who told the truth and wasn���t believed may decide that no adult truly respects children. Biases affect the way we view and treat others and therefore impact the character���s ability to relate to people in a healthy way.

As you can see, characters, like real people, adopt emotional shielding as a way of protecting themselves. But this shielding actually does the opposite. It creates dysfunction in relationships and undermines the character���s ability to succeed at work and in her passions.

The emotional shielding resulting from a wound can actually impact her basic human needs, creating a void: new flaws rob her of love and belonging as her relationships are compromised; the false belief takes aim at her esteem, destroying her self-worth; growth and self-actualization screech to a halt because the character is so focused on what happened in the past that she���s unable to move forward into the future.

This is why it���s so important to know your character���s wound and what kinds of shielding have resulted from it. This information will tell you exactly who your character is in your story, what beliefs or habits are holding her back from achieving her goal, and what she���ll have to do to overcome the trauma and take steps toward wholeness.

Once you���ve identified your character���s wounding event, here are a few helpful questions to ask:

What flaws might my character adopt as a way of keeping the event from occurring again? On the flip side, which positive traits might she downplay or reject because she believes they contributed to what happened (kindness, generosity, obedience, being trusting, etc.)?What dysfunctional behaviors could flow out of these changes in her personality traits?What lie might the character believe about herself in the wake of her wounding experience?Are there any biases about other people or groups that might arise because of what happened to her? How might those biases affect her life?Wounding events and their aftershocks are as relevant for our characters as they are for us in the real world. But the resulting emotional shielding is really a combination of a lot of factors that pertain specifically to your character: her personality going into the traumatic event, the wound itself, the lie that emerges, the human need that will be impacted, and so on. Putting it all together can be daunting, but Angela and I are making it easier with the Character Builder at One Stop for Writers.

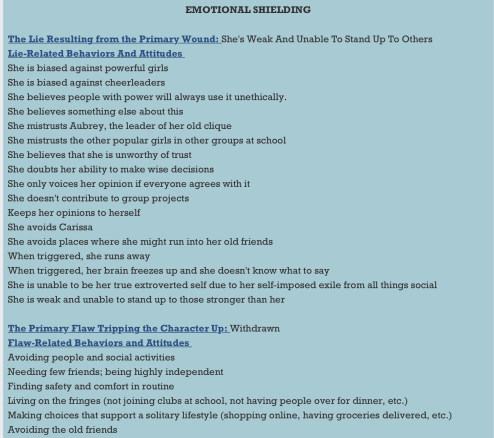

This intuitive tool collects all the necessary information as you figure it out. As you can see with the following example, the Character Builder pulls information from The Negative Trait Thesaurus and The Emotional Wound Thesaurus, providing a list of emotional shielding behaviors and attitudes that make sense for your character in her situation. It removes the guesswork and simplifies the process for you.

(Brainstorming via the Character Builder)

It���s our hope that the Character Builder and the information in this post can help you better understand your own characters. This will enable you to write them realistically in a way that reads true-to-life for your audience.

The post What Is Your Character’s Emotional Shielding and Why Does It Matter? appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

March 20, 2021

Relationship Thesaurus Entry: Acquaintances

Successful stories are driven by authentic and interesting characters, so it’s important to craft them carefully. But characters don’t usually exist in a vacuum; throughout the course of your story, they’ll live, work, play, and fight with other cast members. Some of those relationships are positive and supportive, pushing the protagonist to positive growth and helping them achieve their goals. Other relationships do exactly the opposite, derailing your character’s confidence and self-worth or they cause friction and conflict that leads to fallout and disruption. Many relationships hover somewhere in the middle. A balanced story will require a mix of these dynamics.

The purpose of this thesaurus is to encourage you to explore the kinds of relationships that might be good for your story and figure out what each might look like. Think about what a character needs (good and bad), and build a network of connections for him or her that will challenge them, showcase their innermost qualities, and bind readers to their relationship trials and triumphs.

Description: Acquaintances are the people that your character knows, but just a little: the friend of a friend, the barista at the coffee shop, the guy who always sits across the aisle on the bus. These relationships are typically pretty surface ones, but even an acquaintance can be used to teach a lesson, be a cautionary tale, act as a contrast, inject humor, or provide necessary conflict.

Relationship Dynamics:

Below are a wide range of dynamics that may accompany this relationship. Use the ideas that suit your story and work best for your characters to bring about and/or resolve the necessary conflict.

A relationship typified by surface politeness (the two people acknowledging one another, always saying “hello,” etc .)

Asking small-talk-type questions about the acquaintance’s life

Looking for common ground

Including the acquaintance whenever they’re around

Making an attempt to recall important details from past exchanges (their name, their interests, a difficult time they were going through, etc.)

Seeing a need in the other person’s life and offering to help

Empathizing deeply with the acquaintance’s circumstance even though the character doesn’t know the person particularly well

Picking up on the other person’s cues (recognizing when they’re uncomfortable or want to exit the conversation, etc.)

Avoiding eye contact so the character doesn’t have to chat

Forgetting the person’s name or past conversations���not making an effort

Only being polite to the other person when it benefits the character

Making judgments or forming opinions about the acquaintance based on superficial or incomplete information

Ignoring the acquaintance; acting as if the character doesn’t know them

Conflicting Desires that Can Impair the Relationship

One person wanting a deeper relationship than the other

One person wanting something specific from the other person, such as information or access to a mutual friend

One person wanting to chat while the other just wants to be left in peace

The character wanting to kill time while the acquaintance wants to get to know the character

One person wanting to exit the conversation while the other keeps talking

One acquaintance wanting to meet a deep need while the other person doesn’t want to accept help from him/her

The acquaintance wanting to proselytize or selling something while the character just wants to be left alone

Clashing Personality Trait Combinations: Abrasive and Oversensitive, Cynical and Optimistic, Mischievous and Humorless, Gossipy and Private, Irrational and Sensible

Negative Outcomes of Friction

Losing out on a relationship that could have deepened into a meaningful one

Losing a possible ally

Awkwardness in social situations where the character and acquaintance will both be

The character saying something they wouldn’t say to a close friend, and regretting it

Turning down an offer of help and having to suffer along in isolation

The friction causing tension in relationships with mutual friends

Fictional Scenarios That Could Turn These Characters into Allies

A personal tragedy that the character doesn’t want to share with good friends, but they feel comfortable talking about it with someone they’re not close to

A mutual friend getting into trouble and needing their help

A situation in which the character can use a skill or strength to help the acquaintance out

An acquaintance stepping into a dangerous situation for the character���i.e., pretending to be an old friend to get the character away from a controlling or abusive date

Ways This Relationship May Lead to Positive Growth

The character treating the acquaintance differently than they treat close friends and recognizing a flaw that needs to be addressed

The character realizing the tendency to open up with strangers but not with friends, and seeing a need to change this pattern

The character learning that stepping out of their comfort zone can be a good thing

Themes and Symbols That Can Be Explored through This Relationship

A Fall from Grace, Alienation, Beginnings, Health, Hope, Illness, Perseverance, Pride, Religion, Stagnation, Suffering, Superstitions: Bad Luck, Superstitions: Good Luck

Other Relationship Thesaurus entries can be found here.

Need More Descriptive Help?

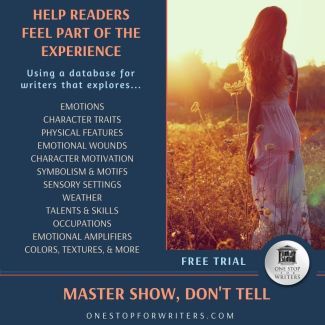

While this thesaurus is still being developed, the rest of our descriptive collection (15 unique thesauri and growing) is accessible through the One Stop for Writers THESAURUS database.

If you like, swing by and check out the video walkthrough, and then give our Free Trial a spin.

The post Relationship Thesaurus Entry: Acquaintances appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

March 18, 2021

Phenomenal First Pages Contest

Yes, you heard that right! The contest formerly know as Critiques 4U has a new name: Phenomenal First Pages. Nothing else has changed. It’s the same monthly first-page critique contest that you’ve come to know and love, just with more alliteration.

And this month, the wonderful Marissa Graff is back to provide feedback for two lucky winners!

If you���re game to enter this month���s contest, here���s the amazing person you could be working with:

Marissa has been a freelance editor and reader for literary agent Sarah Davies at Greenhouse Literary Agency for five years. In conjunction with Angelella Editorial, she offers developmental editing, author coaching, and more. She specializes in middle-grade and young-adult fiction, but also works with adult fiction. Marissa feels if she���s done her job well, a client should probably never need her help again because she���s given them a crash-course MFA via deep editorial support and/or coaching.

CONTEST GUIDELINES

CONTEST GUIDELINESThis month���s contest will be a little different because Marissa is offering up a critique on the FIRST FIVE PAGES of TWO WINNERS��� stories!

If you���re working on a story opening (anything except erotica, nonfiction, or picture books) and would like some objective feedback, please leave a comment. Any comment :). As long as the email address associated with your WordPress account/comment profile is up-to-date, Marissa will be able to contact you if you win. Just please know that if she���s unable to get in touch with you through that address, you���ll have to forfeit your win.

Please be sure your story opening is ready to go so she can critique it before next month���s contest rolls around. If it needs some work and you won���t be able to get it to her right away, let me ask that you plan on entering the next contest once any necessary tweaking has been taken care of.

Two commenters��� names will be randomly drawn and posted here tomorrow. If you win, Marissa will be in contact to get your pages and offer her feedback.

Best of luck!

The post Phenomenal First Pages Contest appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

March 16, 2021

3 Things Worth Thinking About BEFORE You Start Your Book

Want to write a novel in 2021? Whether it���s your first, fourth or fiftieth manuscript, there are certain considerations that can help you get off the starter blocks. Here are three things I often recommend to writers. (If you have other tips to add, do leave them in the comments!)

1) Your Chapter LengthWhat should your chapter length be? Well, as my writing site Bang2write always says, there���s no rule or standard on anything writing-related. This means it depends ��� but how do we decide?

I think it can be good to consider what other writers have done and/or think about it. This useful article from WordCounter.net breaks it down as follows:

Some writers believe 2500 words per chapter is optimumOthers believe it���s somewhere between 3-5,000 wordsMost writers agree under 1000 words is too shortThey also agree over 5000 words is too longALL writers agree chapter length should be defined by the story

Some writers believe 2500 words per chapter is optimumOthers believe it���s somewhere between 3-5,000 wordsMost writers agree under 1000 words is too shortThey also agree over 5000 words is too longALL writers agree chapter length should be defined by the storyMyself, I usually write chapters somewhere between 1500 and 2500 words. One of the reasons I do this is because I write crime fiction. I like to use cliff-hangers at the end of chapters, plus I know my target audience loves to read on Kindle. Sure enough, lots of my reviews have praised my short chapters on this basis. Result!

TOP TIP: Consider the genre and style you���re writing, as well as your readers��� preferences. This will help you land on a ���ballpark figure��� to aim for if you���re stuck.

2) Your Book���s Overall Word CountJust like chapters, book length should obviously be dictated by the story. That said, it can be very helpful again to consider what other writers have done in the past. It can also be useful to consider what your readers prefer.

A while back, B2W did an informal survey of literary agents, book editors, beta readers, book bloggers and publishers I knew. I asked them their thoughts on ���ideal��� wordcounts for various genres. This is what they came back with ���

Literary and epic fantasy: 100-120KCrime, Romance, Horror, Comedy etc: 70-90KYA and Erotica: 50-70KNovellas: 20-40KShort Stories: Up to approx. 1500-10K(ish)

Literary and epic fantasy: 100-120KCrime, Romance, Horror, Comedy etc: 70-90KYA and Erotica: 50-70KNovellas: 20-40KShort Stories: Up to approx. 1500-10K(ish)Obviously you will have read books that are way outside these word counts, but it is still offers useful perimeter. Another thing worth thinking about: the ���newer��� writer you are, the more you probably want to err on the shorter end. Generally speaking, the more experienced writers tend to get the longer word counts.

TOP TIP: Consider what has gone before in your genre when it comes to overall word count. Also think about ���where��� you are on the writing ladder. If you���re a debut author, try and be as lean as possible.

3) Your DAILY Word CountHow many words can you write daily, weekly, monthly towards your masterpiece? This will obviously be personal and depend on other factors in your life ��� This may include (but is not limited to) such things as your day job, family and/or caring commitments or health challenges.

However, many writers just don���t know where to start with setting targets. This means they set themselves writing targets that are not achievable. As a result, they de-motivate themselves or even get ���blocked��� and come to a complete halt.

I recommend coming up with a word count you can stay on top of easily. This means that every word you go beyond that feels like a BONUS. This sense of positivity can prove useful in spurring you on. For this reason, I think 300-500 words a day on your novel is a great number. I have recommended to this many of my ���Bang2writers��� and they report it has helped them finish their novels.

(Remember, 300 words a day x 30 days = 9000 words! Not too shabby at all.)

However, maybe you can���t / don���t want to write every day? I hear that. I am what I call a ���binge writer���. Instead of writing every single day, I like to splurge words out until I have none left. This means every writing session I aim for approximately 2000 words. I try and do this a minimum of twice a week, meaning my target each week is 4000 words. 4000 words x 4 weeks = 16000 words!

But don���t just listen to me. Here���s the word counts of 5 famous authors, including the prolific Stephen King. (I would have put real money on him having a MUCH higher word count, so just as well I am not a gambling woman!).

Whatever you think is a good word count for you, what���s important is creating a meaningful goal. Once you have this goal, you need to ���Work out a plan on how to achieve itEnsure you have a ���when by��� date to focus youEvaluate your progressTweak as necessaryThe fourth is especially important since LIFE HAPPENS. If you work with that expectation in mind, you are far more likely reach your goal. You know what they say ��� ���Failure to plan is planning to fail���!

TOP TIP: Have a goal in mind and personalised strategy to get it done, as well as ���when by��� date to keep focused.

Good luck!

Lucy V. HaysResident Writing Coach

Lucy V. HaysResident Writing Coach Lucy is a script editor, author and blogger who helps writers at her site, Bang2write.com. To get free stuff for your novel or screenplay, CLICK HERE.��

Twitter �� Facebook �� Instagram

Register Now: MARCH 20TH WEBINAR

Register Now: MARCH 20TH WEBINARJoin Angela as she digs into a myriad of ways we can reveal what���s unspoken or hidden in dialogue exchanges and beyond, including our character���s true motivations and feelings. (If you struggle with showing fresh emotion, this is the webinar for you!)

This two-hour session is only $20. Visit the link below to register:

Hidden Emotion & Subtext: Making Dialogue Crackle with What Isn���t SaidThe post 3 Things Worth Thinking About BEFORE You Start Your Book appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

March 13, 2021

Relationship Thesaurus Entry: Godparent and Child

Successful stories are driven by authentic and interesting characters, so it’s important to craft them carefully. But characters don’t usually exist in a vacuum; throughout the course of your story, they’ll live, work, play, and fight with other cast members. Some of those relationships are positive and supportive, pushing the protagonist to positive growth and helping them achieve their goals. Other relationships do exactly the opposite, derailing your character’s confidence and self-worth or they cause friction and conflict that leads to fallout and disruption. Many relationships hover somewhere in the middle. A balanced story will require a mix of these dynamics.

The purpose of this thesaurus is to encourage you to explore the kinds of relationships that might be good for your story and figure out what each might look like. Think about what a character needs (good and bad), and build a network of connections for him or her that will challenge them, showcase their innermost qualities, and bind readers to their relationship trials and triumphs.

Description: A godparent plays the roll of mentor, encourager, and guide to their godchild. Chosen by the child’s parents, the godparent is a family member or good friend. This relationship can be a close one where the two spend a lot of time together, with the godparent offering advice and correction and taking an active role in the child’s upbringing. In some situations, the godparent is meant to become the child’s legal guardian should anything happen to the parent. Other relationships are more distant, with the godparent sending birthday gifts, praying for the child, or offering support in less intimate ways. This relationship is often associated with Catholicism, though other denominations���and even families with no religious affiliation���have adopted the practice.

Relationship Dynamics:

Below are a wide range of dynamics that may accompany this relationship. Use the ideas that suit your story and work best for your characters to bring about and/or resolve the necessary conflict.

A trusting relationship where advice is eagerly sought after and granted

A godchild viewing their godparent as a trusted confidant

The two hanging out and spending time together

The godchild accepting loving correction from the godparent just as they would from their mother and/or father

A godchild who has a poor relationship with his real parents relying on the godparent for love, guidance, and even protection

The godparent acting as a surrogate parent if a mother or father is not in the picture

The godparent taking over legal guardianship for a godchild whose parents are deceased

The godparent being more of a figurehead who only makes an appearance at birthdays, high school graduation, etc.

A godparent exerting more influence or correction than the child or parents are comfortable with

A godchild being influenced by a godparent whose ideals no longer match those of the family

A godparent breaking trust and sharing the godchild’s confidences with others

A godparent who makes promises but doesn’t keep them

A godchild manipulating their godparent to get what they want

Conflicting Desires that Can Impair the Relationship

A godparent wanting to connect with a godchild who wants to be left alone

A godparent wanting to push their ideas or beliefs onto the godchild

A parent being jealous of the relationship between their child and his/her godparent

A godparent using the godchild for their own nefarious means (brainwashing them, using them to get back at someone, etc.)

A childless godparent seeing the godchild as a surrogate son or daughter, and the godchild not wanting that deep of a relationship

A godchild wanting the godparent to get them out of trouble or keep important information from their parents

A willfully absentee godparent being pursued by a godchild who wants a deeper relationship

Clashing Personality Trait Combinations: Apathetic and Needy, Controlling and Rebellious, Humorless and Playful, Dishonest and Honorable

Negative Outcomes of Friction

The godchild losing a confidant and advocate

Poor communication, pushiness, or disrespect causing a rift in the relationship

The godchild’s interaction with their godparents causing them to lose respect for authority figures in general

The godchild resenting their parents for their choice of godparent

A falling-out between the family and the godparent

A single, unmarried godparent losing the only family they have

Either party lamenting their response to conflict in the relationship and losing confidence in themselves

The child relying too much on the godparent when they should be focused on pursuing or repairing a relationship with their actual parents

Fictional Scenarios That Could Turn These Characters into Allies

The godchild helping the godparent win over a potential romantic partner

The godchild enlisting the godparent’s help with something the parents wouldn’t approve of

The two joining forces to change a parent’s mind about something (letting the child go to sleep away camp, allowing him/her to get their driver license, etc.)

Keeping an important secret

Ways This Relationship May Lead to Positive Growth

One of the two parties realizing their need for help and learning to accept it

A helpless or hopeless child or adult learning that they have something to offer

A child learning to respect and desire wisdom

An adult learning to embrace new ways

A selfish person in the relationship learns to serve someone besides him or herself

One of the parties recognizing the importance of family

Themes and Symbols That Can Be Explored through This Relationship

Betrayal, Coming of Age, Death, Family, Friendship, Illness, Inflexibility, Isolation, Passage of Time, Rebellion, Refuge, Religion, Rite of Passage, Sacrifice

Other Relationship Thesaurus entries can be found here .

Need More Descriptive Help?

While this thesaurus is still being developed, the rest of our descriptive collection (15 unique thesauri and growing) is accessible through the One Stop for Writers THESAURUS database.

If you like, swing by and check out the video walkthrough, and then give our Free Trial a spin.

The post Relationship Thesaurus Entry: Godparent and Child appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

March 11, 2021

Writing Process vs. Product: Do You Focus on the Doing or the Having?

Which is more important���the process of writing or the product that results? It’s not something we think much about, but as creatives, one of these two things is typically motivating us. And it’s good to know what our drivers are. I’m glad David Duhr is talking about this today, because it’s providing a lot of food for thought.

When I meet with a new book coaching client I always start our first session with two questions:

Why do you want to write a book?

Why do you want to publish a book?

Between you and me, here���s what I���m really asking: Which is more important to you, process or product?

For some writers, publishing a finished product is the only goal, the writing itself the tedious obstacle standing in the way. For others, the allure lies in the creative act, the getting there, and publication is a consideration consigned to the future, if ever.

If you���re not sure which group you belong to, contemplate this (and then let us know your answer in the comments!):

Would you rather wake tomorrow morning to find your name on the front of a pristine, freshly published book but with no recollection of having written it? Or would you prefer to relish the years-long process of writing your masterpiece, even if no one ever reads it but you?

Therapy for the Artistically Challenged

There���s an old Northern Exposure episode that does a great job of driving this point home. One of the characters, Holling, has taken up painting by number. He only mildly enjoys the hobby but is monstrously attached to the product.

When his wife, Shelly, says his latest landscape should go on their tavern���s wall, Holling says, ���You think it���s that good?��� I.e., is this painting even more impressive than he already believes it to be?!

So Holling displays the painting in the bar, opening himself up to praise but also to that thing so many of us fear so intensely: Criticism.

���Hell, that���s not painting,��� another character says with a scornful laugh. ���That���s paint-by-numbers. That���s therapy for the artistically challenged. That���s what they prescribe for cretins in dayrooms.���

Cold Ice Water & Hot FireAs artists ourselves we���re crushed on Holling���s behalf, having too-easy recall of our own ���Hell, that���s not painting��� moments. Here���s one of mine:

One day I sent my beta reader a new story. I was helplessly, hopelessly in love with it, and I knew he would be, too. I basically said as much when I sent it: ���You���re going to love this one. I think it���s the best thing I���ve ever written.���

He replied ��� in caps ��� ���I DO NOT LIKE THIS STORY.���

I imagine I looked like Holling when I read that. I almost gave up writing entirely, just like Holling vows to abandon painting.

���The more I got into [painting],��� he says to fellow artist Chris, ���the more I thought, well, maybe I���ve got a little talent.���

���Oh, and now you don���t?��� Chris says.

Those critical comments, Holling tells Chris, were like a bucket of ice water being dumped on his head.

We all know that feeling. Harsh criticism can take a writer���s breath away. The only way to avoid it is to not show your work���to undergo the process but keep to yourself the product. (At which point you have only to deal with your internal critic.)

Art ��� Is a ProcessQuasi-philosopher Chris tries to reframe the way Holling approaches his art. ���You���ve got a very basic problem,��� he says. ���You���re confusing product with process. Most people, when they criticize, they���re talking about product. Now, that���s not art ��� that���s the result of art. Art ��� is a process.���

To drive home his point, Chris drags a bewildered Holling into the basement and urges him to slide the painting into the furnace. ���It���s not your painting anymore,��� Chris says. ���It stopped being your painting the moment you finished it.���

And a reluctant Holling nudges his work into the flames.

The Doing and the HavingBy going to that extreme ��� and sometimes we must go to extremes ��� Holling learns a few lessons I���d like to learn: By not investing the whole of his artistic identity in the quality of the result, he can…

enjoy both process and product.

appreciate the product even if it’s not perfect.

recognize the progress he’s made since beginning the journey.

break free from the need for validation by others.

Fast-forward to a reinvigorated Holling again painting by number���but now happily, while giving away his products to friends.

���You���re cranking ���em out like sausages, babe,��� Shelly says.

���You know, Chris says it���s all in the doing,��� Holling says. ���Tell you the truth, I think there���s a lot to be said for the having.���

That���s the space I���d like to live in. I���m planted firmly in the process-oriented, burn-the-product-with-fire camp, but partly because I find it difficult to tolerate my finished work, and showing it fills me with dread. For example, I���ve loved writing this post, but I���m sure I���ll find the result unspeakably repugnant. So the question becomes: If I liked my writing but not the act of writing it, would I still write?

Probably. There���s no right or wrong here.

If publication is what matters to you, undertaking the process is the only way to get there. Draw whatever nourishment from it you���re able. If none, so be it.

If the process is where it���s at for you, enjoy it. Dwell in it, feed off of it. If at the end, you want to publish, cool; if not, cool. Enjoy the journey, and to hell with the destination.

But if you can find your way to appreciating both, crank ���em out like sausages and enjoy the doing and the having.

David Duhr is a writing coach and co-founder at WriteByNight, where he blogs weekly. He���s also fiction editor at the Texas Observer and a member of the Yak Babies books podcast.

You can find his writing in the Dallas Morning News, Publishing Perspectives, Electric Lit, and many others.

Need Help Showing Your Character’s Hidden Emotion? MARCH 20TH WEBINAR

MARCH 20TH WEBINAR Join Angela as she digs into a myriad of ways we can reveal what’s unspoken or hidden in dialogue exchanges and beyond, including our character’s true motivations and feelings. (If you struggle with showing fresh emotion, this is the webinar for you!)

This two-hour session is only $20. Visit the link below for more information & to register.

Hidden Emotion & Subtext: Making Dialogue Crackle with What Isn’t SaidThe post Writing Process vs. Product: Do You Focus on the Doing or the Having? appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

March 9, 2021

Should We Think of Our Setting as a Character?

We���ve probably all heard some variation of the advice to develop story settings that feel like characters. Hogwarts castle in the Harry Potter story world, the Overlook Hotel in The Shining, and East and West Egg in The Great Gatsby are all frequently listed as examples of settings that come alive in readers��� imaginations.

However, we also know that not all advice applies to every writer or story. So let���s dig into this idea: Should we apply the advice ���think of your setting as a character��� to our story���and if so, how?

The Building Blocks of Our StoryNewer writers often conflate the terms story and plot, but plot is just one piece of our story. In general, the biggest story elements are:

CharacterPlotSetting

We could usually change the voice or mood or point-of-view (or other various elements) and still have the same basic story. But if we change the bigger elements, the chances are higher that the story itself would change on a fundamental level.

Not always, of course.

Stories focused on character arcs can often swap out plot points and end up with the same story-level insights into how the characters learn and grow in the face of whatever challenges we choose for the plot. Conversely, we���ve likely all come across plot-focused stories where character inconsistency is the norm because they���re just puppets doing what the plot needs them to do.

Similarly, settings can be hugely important to some stories and mere background to others. One option isn���t ���right,��� and the other option isn���t ���wrong������there are simply different types of stories. We need to figure out what type of story we have (or want to have) and make sure our setting supports that goal.

What Type of Story Do We Have?How much does the setting of our story matter? We can ask ourselves:

Does our story have a recurring setting?Could our story take place almost anywhere?What would change (if anything) if our setting were different?

For example, some stories don���t revisit settings, so the setting is important only if the overall story world is worth a deeper study. (Think of the development of Tolkien���s Middle-earth world even though the Lord of the Rings story follows the characters on a ���road trip��� without recurring settings.) Or for another example, the setting for a story in a generic office might be important only for readers to know that the story takes place in a real-world-style contemporary office.

It’s the need (or desire) for a specific type of setting that matters ��� whether that means a specific type of story world, a specific atmosphere in a house, a specific culture of a workplace, etc. Going back to our generic office example, a fuller setting development might be helpful if we wanted to use specific setting details to add layers to our story, such as reflecting the emotions of our characters or story mood, creating a metaphor for our character���s experience, etc.

If that���s not the case, there���s nothing wrong with ignoring the ���treat settings like characters��� advice. We���re simply not writing that type of story, and we don���t need to overthink the details of our setting.

How Do We Treat Our Setting as a Character?While many of us enjoy reading stories where settings come to life, we often struggle to write such settings ourselves. (Of course, with their Urban and Rural Setting Thesaurus books, blog posts, and Setting Planner Tool, Angela and Becca have plenty of tips for writing settings!)

If we think of our setting as a character, we can add development along the lines of:

Personality and Backstory: Our characters��� backstory gives them a certain personality that we keep consistent throughout our story (unless they have reasons to act out of character). Similarly, the history or culture of a place can develop the ���rules��� and personality of our setting, and when we follow those rules consistently, we create a world that feels realistic (no matter how fantastical it is).Emotional Aspects: When writing characters, we include details beyond physical description that help readers recognize who the character is on the inside. We can include deeper descriptions with our settings too:

Personality and Backstory: Our characters��� backstory gives them a certain personality that we keep consistent throughout our story (unless they have reasons to act out of character). Similarly, the history or culture of a place can develop the ���rules��� and personality of our setting, and when we follow those rules consistently, we create a world that feels realistic (no matter how fantastical it is).Emotional Aspects: When writing characters, we include details beyond physical description that help readers recognize who the character is on the inside. We can include deeper descriptions with our settings too:Does the setting evoke a certain mood or atmosphere (cold and unforgiving or vibrant and peaceful)? Does it symbolize something to characters (or to readers)? Does it reflect the emotions of the characters (a messy house for a messy mind, etc.)? Is it hiding secrets or built on lies? Are there iconic details that can make the setting recognizable as this specific place? How might readers emotionally connect to the setting?Conflicts: Just as characters come into conflict with each other, settings can trigger conflicts as well. (Angela and Becca���s Setting Checklist shares many conflict ideas.) From urban/rural to historical/modern, settings and environments affect everything from culture, rituals, and expectations to common obstacles and attitudes. How does our setting interact and influence our characters and our plot (and vice versa)?Arcs of Change: Our settings can change over the course of a story the same as our characters. They might change with the seasons, plot events might affect them physically (destruction from the villain, new trees planted, etc.), or our characters might simply perceive our setting differently as they���ve changed throughout the story.The Benefits of a Well-Developed Setting

We need only to think of our own experiences as readers to know what a well-written setting can do for our story. Countless readers wished for their own invitation letters to Hogwarts (never mind all the dangers experienced in every book!) so they could experience the wonder of Harry���s first visit for themselves.

Just as readers form emotional connections to characters, they can form emotional connections to settings. Sometimes those emotional connections to settings can be even stronger than to any specific character, such as with the Chronicles of Narnia series that swapped protagonists several times.

For another example of how much settings can matter, here in the U.S., generations of kids grew up with The Brady Bunch TV show, and the HGTV cable channel recently spent millions remodeling the original house used for the exterior of the Brady family���s home to have an interior to match the late-1960s/early-1970s studio sets. The HGTV show following the remodel project turned into their highest-rated series ever, and Brady Bunch fans helped crowd-source furniture and household items to stock the rooms and then competed for a chance to spend a week living in the ���old-fashioned��� house. That setting felt iconic and meaningful to viewers, and the same can happen with our stories.

When it fits our story, treating our setting as a character can give readers more reasons to emotionally connect to our story, and that���s always a good thing. *smile* Do you have any questions or insights about settings or when and how to fully develop them?

Jami GoldResident Writing Coach

Jami GoldResident Writing Coach After muttering writing advice in tongues, Jami decided to put her talent for making up stuff to good use. Fueled by chocolate, she creates writing resources and writes award-winning paranormal romance stories where normal need not apply. Just ask her family���and zombie cat. Find out more about Jami here, hang out with her on social media, or visit her website and Goodreads profile.

Twitter �� Facebook �� Pinterest

Need Help Showing Your Character’s Hidden Emotion? Don’t Miss this Upcoming Webinar.

Need Help Showing Your Character’s Hidden Emotion? Don’t Miss this Upcoming Webinar.Join Angela on March 20th as she digs into a myriad of ways we can reveal what’s unspoken or hidden in dialogue exchanges and beyond, including our character’s true motivations and feelings. (If you struggle with showing fresh emotion, this is the webinar for you.)

More information & registration: Hidden Emotion & Subtext: Making Dialogue Crackle with What Isn’t Said

The post Should We Think of Our Setting as a Character? appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

March 8, 2021

How to Show Hidden Emotion and Subtext

Everybody lies.

You do.

I do.

And our characters certainly do, too.

It doesn’t make us evil, callous, or bad…it’s a defense mechanism. When a person is uncomfortable, under pressure, or doesn’t feel safe, they hold back. It might be information, what they really want or need, their true opinions, or something else. But under it all, what’s really being hidden is EMOTION.

In fiction, we see this happen in almost every dialogue exchange. Our characters say one thing but feel another, yet carefully hide those emotions to avoid feeling exposed and vulnerable. They worry others will judge them, view them as weak, or use their emotions against them.

No matter what the reason is for holding back, writers face a big challenge because they must show what’s on the surface AND what’s hidden (subtext) so readers are always in the loop.

So how can writers show what a character is attempting to hide from everyone else?

So how can writers show what a character is attempting to hide from everyone else? Come find out!

Upcoming WebinarHidden Emotion and Subtext: Making Dialogue Crackle What Isn’t SaidLooking to up your show-don’t-tell game when it comes to character emotion? Then this is the webinar for you. Join Angela as she digs into hidden emotion, subtext, and the truckload of ways to show what’s happening beneath the surface and use it to pull readers in.

When: Saturday, March 20th, 11 am MST

Where: Zoom (Limit of 100 people)

Who: Angela Ackerman

Cost: $20 (2-hour session)

REGISTER HERECan’t make it live? Don’t worry, a limited time recording will be made available.

(If interested, don’t wait too long to register. The last time Angela gave this webinar it filled up, which is why she wanted to offer it again for any who missed it.)

See you there!

The post How to Show Hidden Emotion and Subtext appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

March 6, 2021

Relationship Thesaurus Entry: Guard and Prisoner

Successful stories are driven by authentic and interesting characters, so it’s important to craft them carefully. But characters don’t usually exist in a vacuum; throughout the course of your story, they’ll live, work, play, and fight with other cast members. Some of those relationships are positive and supportive, pushing the protagonist to positive growth and helping them achieve their goals. Other relationships do exactly the opposite���derailing your character’s confidence and self-worth���or they cause friction and conflict that leads to fallout and disruption. Many relationships hover somewhere in the middle. A balanced story will require a mix of these dynamics.

The purpose of this thesaurus is to encourage you to explore the kinds of relationships that might be good for your story and figure out what each might look like. Think about what a character needs (good and bad), and build a network of connections for him or her that will challenge them, showcase their innermost qualities, and bind readers to their relationship trials and triumphs.

Description: When charged or convicted of a crime, a person is taken into custody and placed in a secure cell, either alone or with others. One or more guards monitor those incarcerated to ensure they and others are safe. Guards enforce rules, transport prisoners from their cell to other secure areas, accompany them to hearings, necessary appointments, and other court-appointed appearances. Generally their job is to tell the prisoner what to do, where to go, and how to behave. Because guards have power and authority while prisoners have none, what this ultimately looks like depends on the ethics of the legal system in place and the rules and regulations guards are bound by as they carry out their duties.

Relationship Dynamics:

Below are a wide range of dynamics that may accompany this relationship. Use the ideas that suit your story and work best for your characters to bring about and/or resolve the necessary conflict.

Invading privacy as part of the job, searching an inmate or their cell for contraband and weapons

Working to keep prisoners calm during stressful moments (after family visits, when an appeal is overturned, after sentencing, etc.)

Cracking down on disruptions to enforce peace

An inmate having a legitimate problem that guards don’t take seriously

An inmate feeling micromanaged and constantly watched by authority

A guard intervening in a conflict to protect a prisoner from other inmates

A prisoner who tries to uncover a guard’s weaknesses to manipulate them

A prisoner who incites others to cause trouble for the guards (for entertainment, to distract them, or to put them in peril)

Guards trying to get information from prisoners via threats, force, or punishment

Taking away items from a prisoner to remind them who is in charge

Turning a blind eye to cruelty or violence unless it reaches a certain level

A guard who takes discipline too far and badly injures a prisoner

A guard who uses their position of power for gain (taking bribes, demanding sexual favors, etc.)

A guard being paid to pass on messages, contraband, or to arrange for special privileges

Trying to intimidate a guard by making threats to use outside connections to hurt a guard’s family

Conflicting Desires that Can Impair the Relationship

Prisoners wanting to escape the guards keeping them locked up

Inmates who struggle with authority figures

Guards trying to turn a prisoner into an informant when the prisoner knows that will get them killed

Wanting to control the actions of a prisoner prone to violence

Wanting to get revenge on a guard when he or she has all the power

Knowing a guard is unethical and sadistic and being unable to do anything about it

Clashing Personality Trait Combinations: Manipulative and perceptive, dishonest and trusting, controlling and independent, private and controlling, disrespectful and proper, evil and alert

Negative Outcomes of Friction

A prisoner attacking a guard

A fatality resulting from a brawl

A prisoner getting hold of a weapon and using it on a guard

A prisoner inciting a riot

An inmate gaining leverage over a guard (threatening their family, or uncovering a crime and threatening to expose the guard)

Fictional Scenarios That Could Turn These Characters into Allies

A prison riot where both are being targeted by the same enemy

When the guard takes an interest in an inmate looking to turn their life around

When a guard is overtaken and an inmate steps in to help

When an inmate is the target and the guard steps in to save them

Ways This Relationship May Lead to Positive Change

Jaded guards may encounter prisoners who are ready to make big changes in their life and regain the belief that not every criminal is irredeemable

Prisoners might make changes to their life because a guard takes the time to get them involved in something positive (a re-education program, therapy, community service, support group, etc.)

A guard may realize this job is taking too much, sapping their hope and belief in humanity, and as a result, make a career change that leads to greater fulfillment

A prisoner may see corruption or discrimination happening within the prison system and seek to bring about reform

Themes and Symbols That Can Be Explored through This Relationship

A Fall from Grace, Betrayal, Crossroads, Danger, Endings, Enslavement, Evil, Freedom, Friendship, Hope, Inflexibility, Innocence, Isolation, Journeys, Obstacles, Passage of Time, Perseverance, Rebellion, Sacrifice, Stagnation, Suffering, Transformation, Violence

Other Relationship Thesaurus entries can be found here.

Need More Descriptive Help?

Need More Descriptive Help?While this thesaurus is still being developed, the rest of our descriptive collection (15 unique thesauri and growing) is accessible through the One Stop for Writers THESAURUS database.

If you like, swing by and check out the video walkthrough, and then give our Free Trial a spin.

The post Relationship Thesaurus Entry: Guard and Prisoner appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

March 4, 2021

11 Techniques for Transforming Clich��d Phrasings

One of the things that pumps me up the most when I���m reading a book is when the author phrases things in a way I���ve never seen before. It could be a familiar concept or image���red hair, an urban street, fear���but when it���s written differently, I���m able to visualize that thing in a new way, as if I���m seeing it from a new angle.

This idea of turning tired phrases into new and interesting ones has intrigued me for a while���so much so that I have a notebook full of samples I���ve found in various books. When I get stuck trying to describe something in my own writing, I study those passages to see how the author was able to put a new twist on a well-used phrase. As a result, I���ve figured out a couple of tricks for how we can amp up our descriptions for both fiction and nonfiction works.

The beauty of these techniques is that they work for settings, physical features, character emotion���all kinds of descriptions.

1) Ask Questions to Drill Down and Find the Perfect PhraseWriting is hard work. Sometimes, when we get hung up on a certain passage, it���s easiest to fall back on the phrasings that are most comfortable: butterflies in the stomach, snow that sparkles like diamonds, a peaches-and-cream complexion, etc. To move beyond these clich��s, focus on one aspect of the description and experiment with new ways to describe it. Take this sentence, for instance:

Her eyes are like the lit end of a cigarette, burning into me.

~Al Capone Does My Shirts, Gennifer Choldenko

What a great way to express an angry gaze. You can almost imagine the author���s brainstorming process: How do the eyes burn? What do they look like as they���re burning? What description could I use that expresses both the anger in her eyes and the way they make the viewpoint character feel? This is a great example of how a potentially clich��d phrase can be freshened up with a little extra thought and effort.

2) Mix Up The SensesOftentimes, our passages fall flat because they���re described with the most obvious senses: objects have visual descriptors, and sounds are given auditory comparisons. But mixing the senses can often create a fuller, more layered description.

Their voices were loud and rough and had the sharp edges of crushed-up beer cans. ~Breadcrumbs, Anne Ursu

Here, two of the senses are employed to show us how the voices sound: auditory (loud and rough) and textural (the sharp edges of beer cans). Mixing the senses not only makes for unexpected descriptions, it���s also a great way to add dimension and draw readers a bit more into the story.

3) Play With New Words���entwined as if nothing could ever shoehorn them apart.

~Daughter of Smoke and Bone, Laini Taylor

I never would���ve thought to use the word ���shoehorn��� here. The obvious choice is pry or tear them apart. But obvious choices, over time, lose their impact and end up sounding flat. Taking the time to explore other word choices can result in a phrase that sounds totally different.

���with eyelashes so spiderleg long���

~The Sky Is Everywhere, Jandy Nelson

And don���t underestimate the impact of making up a brand new word. Just be sure that it���s a perfect fit, so it doesn���t read strangely.

4) Add An Element Of EmotionDescriptions often read a bit boring because they simply show how something looks, or feels, or sounds. They���re one-dimensional. Emotion, on the other hand, is stirring, awakening physical and emotional sensations inside the reader. When we add an element of emotion to a descriptive phrase���especially when the feeling isn���t overtly mentioned���it adds depth, like in the following example:

He���s not the father I need. He���s a faulty operating system, incompatible with my software.

~Speak, Laurie Halse Anderson

There���s no mention of emotion here, but it still comes through because Anderson has used a comparison that expresses disconnectedness and resulting sadness. Readers are smart, and they appreciate subtlety. Choose comparisons that convey the right emotion and it will come through for readers.

Bonus Resource: The Emotion Thesaurus. Use this collection of emotions to exactly identify the feeling you want to highlight so you can infuse it into your passage.

5) Use Unusual Comparisons

Something deep and painful wrenched out of him, like nails splintering wood as they pulled free.

~Daughter of Smoke and Bone, Laini Taylor

This example is one of my all-time favorites because it accomplishes so much. Taylor adequately conveys the character���s emotion through an unusual but perfect comparison: the sound of nails pulling out of a wood plank. We���ve all heard that noise; it makes me wince just thinking about it. Using this sound to describe someone���s pain is so much more effective than claiming that his heart ached or his chest hurt. To create a description that resonates with readers, experiment with different comparisons.

6) Add PersonificationFather���s silence is not merely the absence of sound. It���s a creature with a life of its own. It chokes you. It pinches you small as a grain of rice. It twists in your gut like a worm.

~Chime, Franny Billingsley

Here, the author could easily have said that the father was a man prone to awkward silences. Instead, she used personification to bring those silences to life. They don���t merely make others feel uncomfortable; they pinch, and choke, and twist. This gives life to the father���s typically inanimate moodiness, making it much more active and intentional. With the added personification, this example packs a heavy punch.

7) Zoom OutWriters are creatures of habit; we get used to seeing things a certain way and describing them from that perspective. But if we zoom out and look at the object as a whole, we���re able to see it and describe it differently.

He was handsome in a way that required a bit of work from the viewer.

~Raven Boys, Maggie Stiefvater

Stiefvater could have focused on the boy���s eyes or musculature or coloring to describe his looks. But by zooming out and viewing him as a whole, she was able to describe him from that vantage point and come up with something new and interesting.

8) Zoom InThis result can also be achieved by zooming in, rather than out:

I���m holding it so tight my pulse punches through my fingernails.

~If You Find Me, Emily Murdoch

Pulse is one of those emotional indicators that we overuse. It���s always pounding, racing, or thundering like a drumbeat. Here, Murdoch uses this internal sensation in a new way by narrowing in on a part of the body not usually associated with the pulse. And it works because at times of high emotion, you can feel the increased pulse throughout the whole body���even in the tips of the fingers. As this example shows, narrowing the lens can be a great way to describe things from a new perspective.

Bonus Resource: The Physical Feature Thesaurus. Expand your description vocabulary by considering body parts that you’ve never thought of before.

9) Use Contrast

The world felt immense, revolving in the universe with small Susannah McKnight clinging to it.

~Steal Away, Jennifer Armstrong

Some of the things we want to describe are just really difficult. Capturing the immensity of anything���an incredibly small object, big feelings, a large-scale setting���sometimes seems beyond our ability to adequately express. The temptation is to stop the pain and just explain to the reader how big or small it is. A much more compelling technique is to use contrast. Compare the thing to its opposite, and you’ll be able to convey meaning without resorting to telling.

Bonus Feature: One Stop for Writers’ Setting Tutorials. Learn about how to employ various technique and devices to enhance your setting descriptions. The list includes instruction on utilizing contrast, light and shadow, symbolism, hyperbole, and more.

10) CharacterizeHe bristled with latent power as he greeted people with the slippery, handsome accent of old Virginia money.

~Raven Boys, Maggie Stiefvater

I like this passage because it describes this man using characterization rather than a list of physical features. You don���t have a specific picture of what he looks like, but you have a general idea because you know he���s powerful and wealthy and maybe a little slimy. All of that is enough to paint a mental picture. The next time you struggle with describing a new character, consider introducing him with information other than how he looks. Using his job, character traits, quirks, or his values can have a greater and long-lasting impact on readers than a litany of physical features.

11) Mix and Match

Moonlight froze the landscape; everything was a ghost of itself.

~Steal Away, Jennifer Armstrong

This setting description combines multiple techniques. The author has zoomed out to envision the landscape as a whole instead of focusing on the minutia. She also added some personification, as if the moon had used its latent powers to purposely freeze the setting. And a beautifully chosen metaphor creates the imagery and mood needed for the scene.

Bottom line: describing things in new ways is hard work.It takes time and brainpower and more words than using the expected phrasings. But the payoff is multi-faceted, resulting in descriptions that do double duty, reveal something unexpected, and wow the reader. Your new phrasings may be somewhat awkward at first. But with practice, turning a unique phrase will get easier and become a more natural part of your style.

If you���d like to try your hand at rewriting some well-used phrases, here are some examples to play with. Use the techniques mentioned above and see what you can do with one of the following:

Belinda was so mad she could spit nailsSunburned skinA little black dressA dilapidated houseFeel free to share your results in the comments. I���d love to see what you come up with.

The post 11 Techniques for Transforming Clich��d Phrasings appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

Writers Helping Writers

- Angela Ackerman's profile

- 1014 followers