Angela Ackerman's Blog: Writers Helping Writers, page 39

April 13, 2023

What Are Your Protagonist’s Flaws?

The most relatable characters are ones who mirror real people, meaning they are complex individuals with a blend of strengths, failings, attributes, and flaws. Of these four, flaws are often the most difficult to figure out, because knowing which negative traits will emerge in someone means exploring their past to understand who negatively influenced them and what painful experiences they went through. It also means digging up unresolved emotional wounds which have left dysfunction and fear in their wake.

Flaws, or negative traits as they’re also called, are unusual in that the person who has them probably doesn’t view them as dysfunctional and instead believes these traits are helpful and necessary. Why? Because these traits are very good at creating space around your character. And when your character goes through life afraid of being hurt again, keeping people and experiences distant when they seem like they could lead somewhere painful is exactly what your character will want to do.

So, what does this look like?

Let’s take a character who dropped the ball in the past. He was babysitting his nephew, feeding him in the high chair, and the phone rings. He goes to retrieve the phone from his jacket pocket in the other room, and a scream sounds from behind him. His nephew wriggled free from the chair and fell, breaking his arm.

Mom and dad are alerted, and they are not happy.

Moving forward, our character, once the brother who always helped out, stepped up, and volunteered, becomes the guy who shows up late, loses or breaks things, and is always “busy” when asked. What happened? What caused this change?

Easy, that situation with his nephew, and the fallout that came after for not being there when he should have been.

By becoming irresponsible, unreliable, and self-absorbed, what are the chances someone will ask him to take on a big responsibility again? Pretty low. And as long as he’s never the one who has to come through, he’ll never have a chance to fail and disappoint like he did when he was caring for his nephew.

Logically, he was only out of the kitchen for a moment, and whether it were him or the child’s parent, probably the same thing would have happened. But when a person fails, they often take it to heart, blame themselves, and don’t ever want to be put in that same situation (because they’re sure they’ll only screw up). Adopting a character flaw or two will ensure he’s never going to have to worry about dropping the ball again.

Well, heck, that’s great right? No, not at all. Because while his flaws will keep people from requesting he be responsible in some way, he’s also denying himself the chance to be responsible and have a better outcome, which leads to growth and being able to let go of the past. It may also cause friction in his relationship, and even for him to not be there for others when he really wants to be, all because he’s too scared of making a mistake again.

Flaws are normal and natural. We all have them, and so will a character. And in order for them to solve their big story problems and succeed, they will need to examine what’s holding them back…their flaws, and the fears that caused them. So don’t be afraid of giving your character some flaws. Remember, the most relatable characters are those who think, act, and behave just like real people…and that means they’ll be far from perfect.

Now, some writers tend to rush character development in their eagerness to get words on the page, and randomly assign certain flaws without thinking about why they might be there. Unless these aspects of a character’s personality are fleshed out down the road, a character can feel like they lack depth. So make sure you know the “why” behind a flaw…it will help you understand what’s holding them back in the story, how they need to grow, and will point you toward conflict that will trigger them in negatives ways so they become more self-aware. After all, your character won’t realize his negative traits are a problem until failure because of them is staring him in the face.

How do we decide which flaws are right for a character?1) Make Friends with the Character���s Backstory

Backstory gets a bad rap, but the truth is, we need to know it. Understanding a character���s past and what events shaped them is critical to understanding who they are. So brainstorm your character���s backstory, thinking about who and what influenced them, and what difficult experiences they went through that soured their view in some way, damaged their self-esteem, and cause them to avoid certain people and situations. This isn’t so that you can dump a bunch of flashbacks and info-heavy passages into your story to “explain” the source of a flaw. Rather, this information is for you as the author so you better understand what motivates your character, what he fears, and how his goal will be impossible to achieve until he sheds his flawed thinking and behaviors.

2) Poke Your Character���s Wounds

Past hurts leave a mark. Characters who have experienced emotional pain are not eager to do so again, which is why flaws form to ���protect��� from future hurt. A man who loses his wife to an unfortunate infection picked up during a hospital stay is likely have biases toward the medical system. He may grow stubborn and mistrustful, refusing to see a doctor when he grows sick, or seek medical treatment when he knows something is deeply wrong.

This wounding event (his wife���s death) changed him, affected his judgement, and now is making him risk his own health. Had his wife survived, these changes would not have taken place. Knowing your character���s wounds will help you understand how flaws form in the hopes that the character can protect himself from being hurt again.

3) Undermine Your Character���s Efforts

In every story, there is a goal: the character wants to achieve something, and hopefully whatever it is will be an uphill battle. To ensure it is, think about what positive traits will help them achieve this goal, how you can position the character for success. Then brainstorm flaws that will work against them, making it harder. This will help them start to see how their own flaws are getting in the way and sabotaging their progress.

4) Look for Friction Opportunities

No character is an island, and so there will be others who interact with them or try to help in the story. Maybe your character has certain flaws that will irritate other people and cause friction. Relationships can become giant stumbling blocks, especially for a character who wants connection or really needs help but has a hard time admitting it. Make them see how the path to smooth out friendships and interactions is to let go of traits that harm, not help.

5) Mine from Real Life

We all have flaws based on our own experiences, as do all the people around us. Some are small, minor things, others are more major and create big stumbling blocks as we go through life. Flaws are often blind spots, because the person who has them doesn’t see them as a bad thing, just that they have reasons for acting or thinking a certain way, meaning it’s okay. But whenever things don’t go well and we’re frustrated, there’s a good chance one of our flaws is getting in the way.

So, if you’re feeling brave, look within and find the bits of yourself that may not cast you in the best light. Do you get impatient easily? Do you feel like you always have to be in control? Are you sometimes a bit rude, quick to judge, or you make excuses to get out of responsibilities? Thinking about situations where our own behaviors crop up and cause trouble can help us write our character���s flaws more authentically.

If you need brainstorming help…

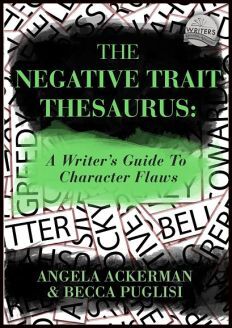

Don’t forget, we wrote the book on this…literally! The Negative Trait Thesaurus: A Writer’s Guide to Character Flaws explores a vast collection of human flaws and shows you how they will cause your character to think, feel, and behave in a certain way. This guide also explains how flaws can be used in the story, and their role in character arc and the necessary change a character must make to minimize or defeat a flaw and achieve their goal.

If you like, zip over here to see a list of the flaws covered in this book, and a few sample entries. Happy writing!

The post What Are Your Protagonist’s Flaws? appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

April 11, 2023

Why Readers Love Anti-Heroes

To understand why readers love anti-heroes, we first need to define what they are. An anti-hero is a flawed, complicated character who thrives in shades of gray. They play the hero of the story, but rarely, if ever, follow conventional expectations of heroism.

Anti-heroes aren���t new. One of the first to emerge was the deeply flawed Huckleberry Finn. Marvel���s Wolverine and Hulk also are deeply flawed anti-heroes. Then came vigilante anti-heroes like Dexter Morgan, who lives by a code. Even though he���s a serial killer, he only murders other killers who���ve escaped justice.

Modern media has grown tired of idealized heroes. Pop culture fell in love with characters who have less-than-heroic traits since they are more relatable. We can���t see ourselves in a hero who stands on a pedestal of perfection. Beloved characters like Jack Sparrow constantly challenge the line between good and bad. Which makes him more relatable than, say, Superman.

Thus, our adoration of the anti-hero is rooted in self-identification with their characteristics and backstories. When characters reflect versions of ourselves, we connect on a deeper level. Our love for these characters stem from empathy. Empathizing with a character immerses us in the fictional world.

Anti-heroes are cool and complex characters that millions of readers adore. Their morality, or lack thereof, makes readers gravitate toward them. It is in our human nature to empathize with people, and what makes anti-heroes so easy to understand is because they are relatable, and typically well-rounded, dynamic characters.

When characters are richly detailed psychologically, we connect to them. If a character is complex enough, it challenges readers��� capacity for understanding others��� beliefs and desires���known as theory of mind���and that challenge can be a pleasant one for fans who like to think deeply about the books they read. Characters who aren���t so black and white, but morally gray, fuel our fascination. Also, perhaps a small part of us wish we could do what they do. Plus, they���re fun characters with snarky, witty dialogue.

Anti-heroes act on impulses we all have but cannot act on, which allows readers to explore what that might feel like. We all have “shadow sides” that contain forbidden impulses, and we need to confront and understand those shadow sides to be our healthiest, most complete selves. Carrying out socially unacceptable things in real life would bring negative consequences and damage our self-concepts but reading safely from the sidelines as our beloved anti-heroes ���walk the walk��� is immensely satisfying.

Dark characters do what they want, unconstrained by social norms. These complex and nuanced characters fascinate and provide a safe way to get in touch with our own forbidden impulses. In short, we love anti-heroes because they reflect the duality of man. Both good and bad traits combine to create a relatable, more human character.

Three Types of Anti-HeroSelf-Interested Anti-HeroUnwilling Anti-HeroVigilante Anti-HeroSelf-InterestedThese anti-heroes tend to have a biting wit, sharp tongue, and a complete disregard for polite society. Their biggest concern is protecting their own interests, even at the expense of others. Fortunately, they aren���t actively trying to harm anyone, and they all have a moral line they won���t cross. If getting what they want would betray their values, they���ll find another way.

Most stories featuring this type of anti-hero focuses on convincing them to fight for the world around them, rather than just themselves.

Unwilling Anti-HeroThese characters are forced to engage with their story���s conflict by the Inciting Incident or First Plot Point, much like the typical hero. However, what makes them an anti-hero is that they spend most of their journey trying to turn back the clock to get out of their new obligations and return to their old life.

By the time they���ve completed the quest, they���ll embrace their new situation and learn to fight for what���s right���even if they continue to complain about it.

Vigilante Anti-Hero

The vigilant anti-hero is by far my favorite to write.

Some, like Jack Reacher, align with the classic ���lone wolf. Others have families and deep personal connections. The vigilante anti-hero rejects authority, doesn���t trust society���s version of justice, and has their own nonconventional sense of morality. When they see evil in their world, they set out to correct it, even if it involves violence, deception, and murder.

As you can imagine, this requires a careful balancing act.

This style of heroism is exciting, but it���s also easy for these anti-heroes to cross the line in villain territory. Because of that, the vigilante anti-hero requires a rock-solid moral compass that is intrinsically good, even if their methods are more complex.

Though some anti-heroes toe the line between good and evil, they���re ultimately more hero than villain.

Have you crafted an anti-hero? What type did you choose? Tell us about them!

If you’d like to see anti-heroes in action, you can find some examples in my latest release.

If you’d like to see anti-heroes in action, you can find some examples in my latest release.Amidst a rising tide of poachers, three unlikely eco-warriors take a stand to save endangered Eastern Gray Wolves���even if it means the slow slaughter of their captors.

The post Why Readers Love Anti-Heroes appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

April 8, 2023

Character Type & Trope Thesaurus Entry: Jester

In 1959, Carl Jung first popularized the idea of archetypes���”universal images that have existed since the remotest times.” He suggested that every person is a blend of these 12 basic personalities. Ever since then, authors have been applying this idea to fictional characters, combining the different archetypes to come up with interesting new versions. The result is a sizable pool of character tropes that we see from one story to another.

Archetypes and tropes are popular storytelling elements because of their familiarity. Upon seeing them, readers know immediately who they’re dealing with and what role the nerd, dark lord, femme fatale, or monster hunter will play. As authors, we need to recognize the commonalities for each trope so we can write them in a recognizable way and create a rudimentary sketch for any character we want to create.

But when it comes to characters, no one wants just a sketch; we want a vibrant and striking cast full of color, depth, and contrast. Diving deeper into character creation is especially important when starting with tropes because the blessing of their familiarity is also a curse; without differentiation, the characters begin to look the same from story to story.

But no more. The Character Type and Trope Thesaurus allows you to outline the foundational elements of each trope while also exploring how to individualize them. In this way, you’ll be able to use historically tried-and-true character types to create a cast for your story that is anything but traditional.

Jester (Archetype)

Jester (Archetype)DESCRIPTION

Jesters are the comedians and tricksters in the story. Their job is to make light of serious things and provide comic relief, but they also can impart wisdom through their shenanigans.

FICTIONAL EXAMPLES: Puck (A Midsummer Night���s Dream), the Fool (King Lear), Timon and Pumbaa (The Lion King), the Genie (Aladdin)

COMMON STRENGTHS: Confident, Easygoing, Enthusiastic, Flamboyant, Friendly, Funny, Happy, Imaginative, Observant, Perceptive, Persistent, Persuasive, Philosophical, Playful, Quirky, Spunky, Supportive, Uninhibited, Whimsical, Wise, Witty

COMMON WEAKNESSES: Abrasive, Addictive, Childish, Disrespectful, Evasive, Foolish, Frivolous, Impulsive, Irresponsible, Mischievous, Reckless, Tactless

ASSOCIATED ACTIONS, BEHAVIORS, AND TENDENCIES

Encouraging others and lifting their spirits when they’re down

Cracking jokes (even in in appropriate situations)

Using self-deprecating humor

Being able to laugh at themselves

Finding humor in every situation

Laughing often

Being able to say things with a humorous twist

Changing the subject when a conversation gets too serious

Pranking others

Spontaneity; trying new things

Living each moment to the fullest rather than planning for the future

Not holding grudges or living in the past; letting things go

Taking things in stride; not being easily ruffled

Remaining neutral rather than taking sides

Exploring or broaching deep topics in a roundabout way���e.g., through the context of a story rather than a one-on-one debate

Going over the top to gain attention (in their appearance, with extravagant pranks, etc.)

Impulsivity

Not knowing when to stop

Taking jokes and pranks too far

Irritating others with their behavior

Using humor as a shield to hide their pain

SITUATIONS THAT WILL CHALLENGE THEM

Serious moments, when humor is unacceptable

Being partnered with someone who doesn’t appreciate humor

Seeing a friend in a difficult situation and being unable to cheer them up or lighten their load

Trying to impart a truth to someone in an indirect way, and them not getting the message

Another jester entering the character’s friend group���one who is funnier, more charismatic, better liked, etc.

INNER STRUGGLES TO GIVE THEM DEPTH

Developing a mental health challenge that makes humor and lightheartedness difficult

Being forced to take a stand on a serious moral issue that will create strife with others

Feeling like they always have to be “up” and fun, even when they’re sad or down

Struggling to care properly for themselves (because they’re always encouraging others and cheering them up)

A traumatic or devastating situation that steals the character’s joy and lust for life

TWIST THIS TROPE WITH A CHARACTER WHO���

Has a serious, deep side

Is interested in current events and uses their gifts of satire, irony, etc. to tackle injustices

Is dry and deadpan instead of flamboyant and melodramatic

Is masking a deep insecurity

Is funny without meaning or trying to be (�� la Adrian Monk)

Has an atypical trait: fussy, timid, proper, cautious, etc.

CLICH��S TO AVOID

��� Funny people with no substance; all they care about is having a good time and making people laugh

��� The preachy jester who always has a message to convey

��� Jesters who are happy and upbeat all the time

��� Jesters with no flaws

Other Type and Trope Thesaurus entries can be found here.

Need More Descriptive Help?

Need More Descriptive Help?While this thesaurus is still being developed, the rest of our descriptive collection (16 unique thesauri and growing) is accessible through the One Stop for Writers THESAURUS database.

If you like, swing by and check out the video walkthrough for this site, and then give our Free Trial a spin.

The post Character Type & Trope Thesaurus Entry: Jester appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

April 6, 2023

Six Ways to Make Your Author Blog More Successful

How can you make your author blog more successful?

Whether you���re just starting a new blog or you have one you���ve been working on for a while, the following steps will help you increase your readership.

1. Ask Yourself: What���s in It for My Reader?By far the biggest mistake I see writers making with their author blogs is making it all about them.

They talk about their books, their writing process, their cats and dogs, their irritating family members, their travels, and sometimes, their meals.

Some writers can create entertaining posts on these topics, but not for long. (There���s only so much you can say about your cat, after all.)

What writers must remember is that they���re competing with millions of other blogs for their readers��� attention.

Think about what makes you stop and read a post. Usually, it���s because the headline promises to tell you something you want to know. Or it intrigues you for some other reason���often because you���re interested in the topic the writer is covering.

When writing a post, pretend you���re standing up in front of a group of strangers to talk about something for 10 minutes. You don���t want your listeners turning to their cell phones because they���re bored. Whatever you talk about, make it interesting to them!

2. Find Your NicheRoughly 70 million posts are posted on WordPress sites alone each month.

To stand out amidst all that competition, it helps to have a unique niche���something to talk about that sets you apart from the rest.

I recommend you combine your personal strengths (are you funny? romantic? organized?) with your writing genre to come up with a unique niche that sets you apart from others.

Let���s say Paula is a thriller writer who is also passionate about flying airplanes. She could combine those two into a niche that would serve her well on her blog. Maybe she writes about thrilling flight adventures, exciting places to fly for vacation, or thrilling crimes that have taken place on or around airplanes.

How about Rose? She is a romance writer who loves gardening. Maybe she could have a blog that combines the two somehow. She could blog about the unique way that plants bring people together, plants that inspire romance or signify love, or how getting back to nature can help relationships.

As long as you choose something that you���re interested in, you can usually blog about it for years to come without getting bored. Choose a topic that���s at least distantly related to what you write about (it doesn���t have to be exact), and you���ll be likely to attract people to your blog who may be interested in your books.

3. Write Longer, Quality ArticlesWhen people first started writing blogs, they were encouraged to write short���500 words or less. That���s changed today.

According to Backlinko, the ideal content length for maximizing social shares is 1,000-2,000 words. SEO company AHREFS also notes that long-form content (about 1,000 words) gets more backlinks than shorter articles���and that helps your posts show up higher in search engine results.

Then, make sure you���re creating quality posts. That means that your posts are deemed helpful, informative, and/or entertaining by your readers. In a survey by GrowthBadger, ���quality of content��� was the #1 most important success factor among all bloggers.

Take some time to craft a good post every time you write one. Make sure you have at least a few solid takeaways for your readers���things they can use to make their lives better in some way.

4. Write Great Headlines and SubheadsThere���s a science to creating ���clickable��� headlines. Fortunately, several companies have researched that science and made it available for us to use.

I highly suggest you use Coschedule���s free headline analyzer to check every blog headline you write. It will ���score��� your headline so you can see the difference between high-performing headlines and those people tend to ignore.

The Advanced Marketing Institute also has a headline analyzer and some helpful information on writing good headlines.

Then don���t forget to include subheads in your post. These are minor headings placed about once every 300 words or less to break up the text.

Most blog readers skim articles rather than carefully reading from beginning to end, so subheads are critical to keeping them on the page.

Headlines and subheads also help increase your SEO score. (Read on!)

5. Learn SEO and Use It!You���ve probably heard about search engine optimization (SEO). If you���re already using it, you���re good to go. But if you haven���t started yet, don���t wait another minute.

SEO activities are those that you use to help your post show up sooner in search engine results. It sounds intimidating, but it’s not.

All you have to do is choose the keywords you want your blog to rank for���words that someone looking for your blog or stories might type into the search engine. Then use those keywords in your headlines, subheads, and articles.

You can learn more about SEO here. Once you have a general idea, make sure your blog has an SEO plug-in on the backend of the website. Yoast SEO has a good one you can use for free that will guide you toward improving your SEO score for each post.

6. Post Consistently!A blog is a commitment. Promise yourself that you will post at least once a week (twice is better) for at least six months. Then check your results and see how you���re doing. (Google Analytics is the best way to see how your posts are performing.)

Orbit Media Studios found in a survey of bloggers that those who published more often were more likely to report ���strong results.��� I���ve found that choosing one day (or night) a week to write a blog helps keep me on track.

It���s easier to post more often and increase traffic if you invite guest authors to your blog. Interview people who are ���experts��� in your niche. You���ll expand your network that way, plus get more quality content for your blog. A win-win.

Yes, there are a lot of blogs out there. But if you find a niche that sets you apart, create quality posts, use SEO, and post consistently, you increase your chances of attracting new readers to your website and potentially to your e-newsletter as well. (I���ll talk more about e-newsletters in my next post!)

Note: Get Colleen���s free report on finding your blogging niche plus free chapters of her award-winning books for writers here!

The post Six Ways to Make Your Author Blog More Successful appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

6 Ways to Make Your Author Blog More Successful

How can you make your author blog more successful?

Whether you���re just starting a new blog or you have one you���ve been working on for a while, the following steps will help you increase your readership.

1. Ask Yourself: What���s in It for My Reader?By far the biggest mistake I see writers making with their author blogs is making it all about them.

They talk about their books, their writing process, their cats and dogs, their irritating family members, their travels, and sometimes, their meals.

Some writers can create entertaining posts on these topics, but not for long. (There���s only so much you can say about your cat, after all.)

What writers must remember is that they���re competing with millions of other blogs for their readers��� attention.

Think about what makes you stop and read a post. Usually, it���s because the headline promises to tell you something you want to know. Or it intrigues you for some other reason���often because you���re interested in the topic the writer is covering.

When writing a post, pretend you���re standing up in front of a group of strangers to talk about something for 10 minutes. You don���t want your listeners turning to their cell phones because they���re bored. Whatever you talk about, make it interesting to them!

2. Find Your NicheRoughly 70 million posts are posted on WordPress sites alone each month.

To stand out amidst all that competition, it helps to have a unique niche���something to talk about that sets you apart from the rest.

I recommend you combine your personal strengths (are you funny? romantic? organized?) with your writing genre to come up with a unique niche that sets you apart from others.

Let���s say Paula is a thriller writer who is also passionate about flying airplanes. She could combine those two into a niche that would serve her well on her blog. Maybe she writes about thrilling flight adventures, exciting places to fly for vacation, or thrilling crimes that have taken place on or around airplanes.

How about Rose? She is a romance writer who loves gardening. Maybe she could have a blog that combines the two somehow. She could blog about the unique way that plants bring people together, plants that inspire romance or signify love, or how getting back to nature can help relationships.

As long as you choose something that you���re interested in, you can usually blog about it for years to come without getting bored. Choose a topic that���s at least distantly related to what you write about (it doesn���t have to be exact), and you���ll be likely to attract people to your blog who may be interested in your books.

3. Write Longer, Quality ArticlesWhen people first started writing blogs, they were encouraged to write short���500 words or less. That���s changed today.

According to Backlinko, the ideal content length for maximizing social shares is 1,000-2,000 words. SEO company AHREFS also notes that long-form content (about 1,000 words) gets more backlinks than shorter articles���and that helps your posts show up higher in search engine results.

Then, make sure you���re creating quality posts. That means that your posts are deemed helpful, informative, and/or entertaining by your readers. In a survey by GrowthBadger, ���quality of content��� was the #1 most important success factor among all bloggers.

Take some time to craft a good post every time you write one. Make sure you have at least a few solid takeaways for your readers���things they can use to make their lives better in some way.

4. Write Great Headlines and SubheadsThere���s a science to creating ���clickable��� headlines. Fortunately, several companies have researched that science and made it available for us to use.

I highly suggest you use Coschedule���s free headline analyzer to check every blog headline you write. It will ���score��� your headline so you can see the difference between high-performing headlines and those people tend to ignore.

The Advanced Marketing Institute also has a headline analyzer and some helpful information on writing good headlines.

Then don���t forget to include subheads in your post. These are minor headings placed about once every 300 words or less to break up the text.

Most blog readers skim articles rather than carefully reading from beginning to end, so subheads are critical to keeping them on the page.

Headlines and subheads also help increase your SEO score. (Read on!)

5. Learn SEO and Use It!You���ve probably heard about search engine optimization (SEO). If you���re already using it, you���re good to go. But if you haven���t started yet, don���t wait another minute.

SEO activities are those that you use to help your post show up sooner in search engine results. It sounds intimidating, but it’s not.

All you have to do is choose the keywords you want your blog to rank for���words that someone looking for your blog or stories might type into the search engine. Then use those keywords in your headlines, subheads, and articles.

You can learn more about SEO here. Once you have a general idea, make sure your blog has an SEO plug-in on the backend of the website. Yoast SEO has a good one you can use for free that will guide you toward improving your SEO score for each post.

6. Post Consistently!A blog is a commitment. Promise yourself that you will post at least once a week (twice is better) for at least six months. Then check your results and see how you���re doing. (Google Analytics is the best way to see how your posts are performing.)

Orbit Media Studios found in a survey of bloggers that those who published more often were more likely to report ���strong results.��� I���ve found that choosing one day (or night) a week to write a blog helps keep me on track.

It���s easier to post more often and increase traffic if you invite guest authors to your blog. Interview people who are ���experts��� in your niche. You���ll expand your network that way, plus get more quality content for your blog. A win-win.

Yes, there are a lot of blogs out there. But if you find a niche that sets you apart, create quality posts, use SEO, and post consistently, you increase your chances of attracting new readers to your website and potentially to your e-newsletter as well. (I���ll talk more about e-newsletters in my next post!)

Note: Get Colleen���s free report on finding your blogging niche plus free chapters of her award-winning books for writers here!

The post 6 Ways to Make Your Author Blog More Successful appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

April 4, 2023

Need Organization Help? Try Trello

Staying organized as a writer can be a huge challenge. We all have other responsibilities, and the crazier life gets, the easier it is for stuff to fall between the cracks���important stuff we can���t afford to forget.

Angela and I are constantly juggling a thousand things, so organization is kind of vital for us. We���ve done a couple of things over the past few years to help with this. First, we hired Mindy, our amazing blog wizard. She���s incredibly capable and enthusiastic, and the work she���s taken off our plates has enabled us to keep on chugging.

But we recognize that this isn���t an option for everyone. Heck, it���s why we took so long to do it ourselves. So I���d like to share another idea with you that anyone can use to stay organized. It���s free and has been a game-changer for us.

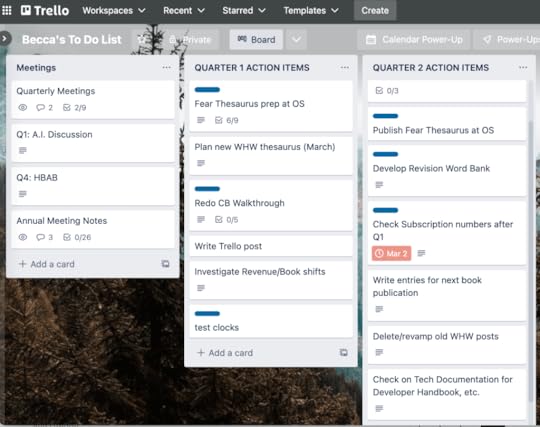

Trello, for the Win!Trello is an online visual tool that allows you to organize projects and track tasks. It���s meant for teams, and Angela and I do use it for our projects, but it has been just as useful for me personally, to keep my own jobs and responsibilities organized.

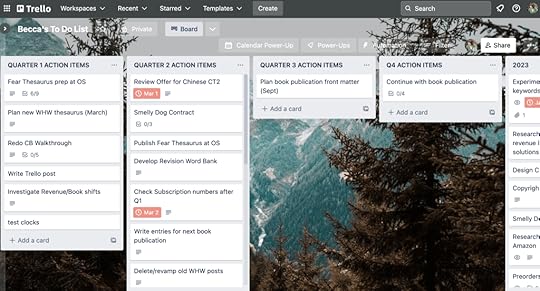

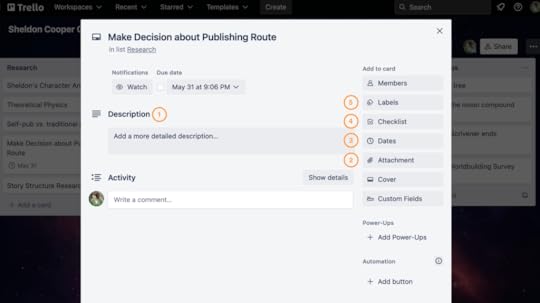

Each board you create consists of lists, and the lists contain cards that can be dragged and dropped to different spots. Here, I���ve created a board for the year, and I���ve used it to break out my tasks by quarter. There���s a list for each quarter, then in each list, I started adding cards���one for each task. This enables me to track what I need to do and prioritize it all by importance and time sensitivity.

I have a number of boards that I use for different purposes. As a writer, you can use Trello boards to do so many things:

Collect story ideas you might want to exploreMake a list of recommended craft books you want to readCompile research links for a book projectStore passages or whole chapters that were cut from your manuscript (to be used later in the story or utilized elsewhere)Curate crutch words or overused phrases to search for when editingTrack edits that need to be made for certain chapters or across a whole manuscriptCreate a list of questions for beta readers to answer once they���ve finished their initial read-through of your manuscriptMake a to-do list for publishing your next bookOrganize a book launch or other marketing eventStore the names and contact information for book reviewers, ARC readers, street team members, and other key peopleRecord processes so you���ll know exactly the steps for importing a file to Scrivener, editing a digital book file, uploading books at a distributor site, or publishing a blog postGather links for cool writerly gifts you can give to critique partners, your agent, an editor, or your cover designerKeep links to spreadsheets, Google Drive folders, Word docs, and YouTube videos for a project all in one spotStore marketing information (bios, cover images, logos, testimonials, press kit info, etc.) in one place for easy editing and accessTrack upcoming speaking engagements or podcast interviews, along with the tasks to complete prior to each oneGather guest post ideas to pitch to blog influencersTrack any tasks that have to be done eventually, but maybe not right nowMy To Do board shows how Trello can be used to organize tasks throughout the year. But it could also be helpful to create a board for your current book project. It might look something like this, with each card containing links and attachments so you can easily access all the items you need.

As you can see, this tool is great for keeping things organized and reminding you when certain tasks need to get done. Whatever you need to track, create a board for it (10 are included in the free membership) and click the +Add A Card option in any of the columns. Add a title, then double-click it to record whatever details are most helpful. Here are a few features that can be added to each card/task:

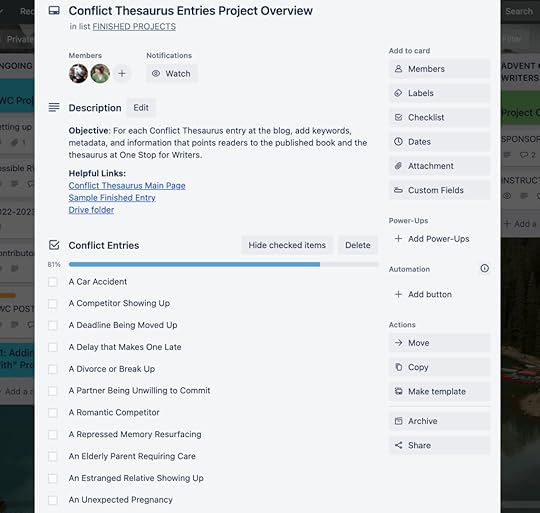

Write a description: Write an overview of this task, and add any links that might be helpful.Attach files for easy reference.Assign a start date or due date. This is super-handy when you have a task that won���t be coming due for a few months, but you don���t want to forget about it. Any date you assign will show up on the card so you can see it from your board. You can also set a reminder so you can be sent an email prior to the event.Create a Checklist (or two, or three…). This is my absolute favorite feature, because what���s better for organization than a list?

Write a description: Write an overview of this task, and add any links that might be helpful.Attach files for easy reference.Assign a start date or due date. This is super-handy when you have a task that won���t be coming due for a few months, but you don���t want to forget about it. Any date you assign will show up on the card so you can see it from your board. You can also set a reminder so you can be sent an email prior to the event.Create a Checklist (or two, or three…). This is my absolute favorite feature, because what���s better for organization than a list?

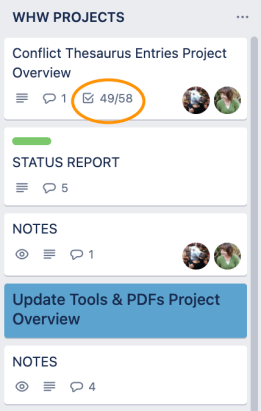

Just create a checklist, give it a title, and start adding items. If those items change in priority, you can drag them into a different order, easy-peasy. As you complete items, check them off, and you���re given a status update indicating how much of the checklist has been completed.

This is helpful because there are times when I think a project is finished, or I get sidetracked with something else and forget about it. Seeing the status line on the card acts as a reminder that I still have some tasks to do.

5. Categorize cards with labels. Sometimes, you have tasks spread across your board that are related in some way. Maybe they���re all part of a certain project, they require more research before a decision can be made, or they���re tasks that someone else is responsible for. Create a label and add it to the appropriate cards. Then you���ll be able to see at a glance the cards that go together. Here, I���ve added a blue label for tasks that are One Stop for Writers related.

Use Trello for Collaboration

Use Trello for CollaborationWriting is more collaborative now than ever before���meaning, you might find yourself one day co-authoring a book, working with other authors on a boxed set, or joining forces for a launch or marketing event. Communicating with other people is super easy on Trello. Just invite the person to your board, and they���ll have access to any lists and cards created there. There���s also a place on each card for comments, so the tasks and projects can be discussed among collaborators.

Let���s face it: there���s so much more to being a successful author than just writing well. Thinking of all the things you have to do can be overwhelming, especially if organization isn���t your strength or you���ve got so much going on that staying on top of it all seems impossible. But as with any area of struggle, sometimes you just need the right tool. Trello has been a lifesaver for me, and I���m happy to share it with you. Because we writers have to stick together.

What tools or resources do you use to stay organized?The post Need Organization Help? Try Trello appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

April 1, 2023

Introducing…The Character Type & Trope Thesaurus!

Character building is hard work, and when we see certain types of characters appear again, and again in fiction and film, we wonder if there’s a way to start with a familiar character building block yet still create someone fresh. And with a little out-of-the-box thinking, we can.

I’m talking about using archetypes and tropes — characters who play a specific role in a story or who have a blend of characteristics that make them instantly recognizable: the Rebel, the Bully, the Hot Billionaire, the Chosen One…you get the idea. Readers recognize these types of characters and may even expect to find them in certain stories.

So, our job is done, right? Pick an archetype or trope, put some clothes on them and shove them into the story. No, ‘fraid not. Character types and tropes can provide a skeleton, but to avoid a stock character or overdone clich��, they must stand on their own and mesmerize by being unique.

And that’s where this thesaurus comes in.

Characters need layers, full stop, so trope or not, we want to dig for what makes them an individual, give them a soul, and make adaptations that will challenge a reader’s expectations.

What this thesaurus will cover:A Trope or Type Description and Fictional Examples. Before we can think about how to adapt a trope, we need to know more about who they are. This overview and examples will help you know if this baseline character is right for your story.

Common Strengths and Weaknesses. A character who aligns with a trope or type tends to have certain positive and negative traits, so we list those as a starting point. But don’t be afraid to branch out – personality is a great place to break the mold.

Associated Actions, Behaviors, and Tendencies. Because tropes have a mix of traits, qualities, and a worldview baked in, you’ll need to know how to write their actions, choices, priorities, and certain tendencies…so you can then decide how to break with tradition.

Situations that Will Challenge Them. Every character faces challenges in a story that are extra difficult because of who they are, what they believe, fear, and need. A trope or type character is no different. We’ll cue up ideas to get your brains whizzing on what this can look like in your story.

Inner Struggles to Give Them Depth. Oh, we’re getting to the good stuff now, people! Whether you start with a type or trope or craft someone from scratch, what makes a character a true individual is everything going on inside of them. Showcasing your character’s inner struggles, emotional tug-o-wars, clashing beliefs and needs…this is how you unearth someone with depth for readers to fall in love with!

Twist This Type With a Character Who… is where we give you ideas on how to break expectations, so you deliver someone who has fresh angles, and isn’t a typical stand-in.

Clich��s to Avoid is where we alert you to some of the overdone versions of a type or trope so you’re aware of them as you develop your characters and plot your story.

Readers are hardwired to look for patterns and familiarityWhich is why we see tropes used so often, but good storytellers know that in 99% of cases, using one is the starting point only. We want rounded and dynamic characters, not flat ones. So, unless you require a stock character to fill a background role, any character who starts as a trope should be as carefully developed as those who did not. Readers want–and deserve!–fresh characters, so dig into those inner layers and bring forth someone unique.

Join us next Saturday for the first entry, and if there’s a character type or trope you’d like us to cover, add it in the comments, and we’ll add it to the list of potentials!

The post Introducing…The Character Type & Trope Thesaurus! appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

March 30, 2023

Does Your Story Need a Hit of Organic Conflict? Look to Your Setting.

Every writer���s mission is to pen a story that draws readers in, offering familiarity when it comes to certain genre expectations while also delivering something fresh so to be distinctive and memorable. This is how to cultivate a loyal–and, fingers crossed, rabidly obsessed–reading audience.

But heck, there���s a lot of stories out there. And didn���t someone say there���s only so many plot forms to choose from? Is ���fresh��� even possible?

YES.

When you know where to look, you can find a kaleidoscope of unique ideas and apply them to any type of story to transform it.

A Story���s Secret Weapon: ConflictOne of the easiest ways to offer that thrill of ���newness��� for readers is to activate the power of conflict. In fiction, it is the crucible that tests, bruises, and shapes our characters. Externally, it pushes the plot onward by supplying the resistance needed to force characters to scrutinize their world, make choices, and take action to get what they want. Internally, conflict generates a tug-of-war between the character���s fears, beliefs, needs, values, and desires. Ultimately, it forces them to choose between an old, antiquated way of thinking and doing, or a new, evolved way of being, because only one will help them get what they want.

Conflict touches everything:

plot, characters, arc, pacing, tension, emotion, etc.

No matter the genre or the type of plot, conflict allows you to make a storyline fresh. The scenarios you choose can be adapted to your character, their circumstances, and the world where everything is taking place, personalizing the experience for readers and drawing them in closer to the characters they care about.

The other beautiful thing about conflict is how you can find it anywhere: the character���s career, relationships, duties, etc., or it can come from adversaries, nature, the supernatural, or even from within themselves. And that���s just to start.

But no matter where your character is and what is happening, there���s one eternal source for conflict that can always lead you to a complication, obstacle, or blocker to clash with your character���s goals: the setting.

Maximize a Scene���s ���Where���The location of each scene contains inherent dangers and risks, meaning you can mine those to create problems and remind the character of the cost of failure. Drawing conflict from your setting also gives it a greater role in the story. Rather than be a ���stage��� for action to unfold, your setting becomes a participant.

Here are some things to keep in mind to draw the very best conflict from your setting, making important story moments more intense, and offering that fresh gauntlet of challenges for your character to navigate.

Choose Settings Thoughtfully

Some setting choices are obvious. If you need your character���s car to break down in an isolated area, then a country road, campsite, or quarry might do the trick. But conflict very often happens in an ordinary setting, like a retail store or at home. In cases like these, when the story has dictated where events will occur, up the ante by choosing a specific location that holds emotional value for your character. Instead of choosing just any store, pick one with an emotional association���such as the place the character was caught shoplifting as a teenager. Good or bad, any setting that plays upon their emotional volatility will increase their chances of saying or doing something they���ll regret.

And while we���re talking about emotional value, don���t underestimate the symbolic weight of the objects within the scene. The backyard may be a generic place to have a difficult conversation but put the characters next to the treehouse their son used to play in before he got critically sick, and you���ve already heightened their emotions, potentially adding additional conflict to the scene.

Use Natural ObstaclesIt���s also important to think about which settings contain infrastructure that will make the character���s goal harder to reach. Maybe it���s a ravine the protagonist will need to cross, a locked door to get through, or a security guard to evade. Remember that the character’s journey to achieve their goal shouldn’t be a walk in the park. Conflict is necessary in every scene, so choose settings that contain obstacles or provide poignant emotional roadblocks.

Think about how conflict naturally evolves. The character has an objective. They put together a plan and start pursuing that goal. Then complications come along and make things interesting. Luckily, there are lots of ways we can manipulate the setting to create additional conflict scenarios.

Level-Up Setting Conflict

Mess with the Weather. Unexpected showers, a heat wave, an icy driveway, the threat of a tornado���how can small and large weather considerations create problems for your character?

Take Away Transportation. No matter what setting you choose, your character will need to move from one place to another. What kind of transportation disruptions will make it harder for them to get where they need to go?

Add an Audience. Falling down in private is totally different than doing it in a crowd of people. Both may be physically painful, but the latter adds an element of emotional hardship. Who could you put in the environment as a witness to the character’s missteps or misfortune?

Trigger Sensitive Emotions. Conflict is easier to handle for an even-keeled, emotionally cool character. So use the setting to throw them off balance. If they’re struggling to put food on the table, place them in a locale where wealthy characters are eating lavishly and throwing away leftovers. Likewise, a character with daddy issues can be triggered in an environment that highlights healthy and loving father-daughter relationships. So when you���re planning the setting for a scene, ask yourself: What could I add specifically for my character in this situation that will elevate their emotions?

Exploit What They Don���t Have. If your character doesn���t have a light source, place them in a dark place, like a cave or deserted subway tunnel. No weapon? Surround them with physical threats. If they’re lacking something vital, capitalize on that.

Make Them Uncomfortable. Vulnerability sets the character on edge and elevates their emotional state. So whenever you can, put the character in a location where they have no experience, don���t know the rules, or aren’t really suited to navigate it. This can work for small- or large-scale settings, from a character who has to traverse an alien planet to someone who’s averse to kids having to host a child’s party.

Use Symbolism. Nothing impedes progress like fear and self-doubt. Think about which symbols can be added to the environment to remind the character of an area of weakness, a past failure, a debilitating fear, or an unresolved wound.

Add a Ticking Clock. One sure-fire way to up the ante is to give the character a deadline. Instead of them having unlimited time to complete the goal, make them dependent upon elements within their environment, such as having to avoid rush-hour traffic, reach the bank by four p.m., or get home before sunset.

Setting-related conflict is fantastic in that it can be endlessly adapted, helping you keep the tension going in every scene no matter where your character is.

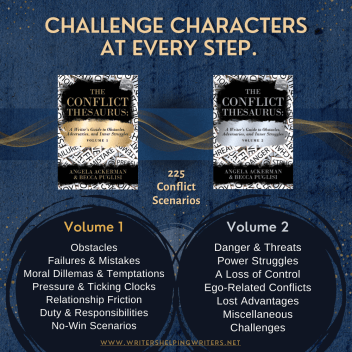

Need More Help with Unleashing the Power of Conflict?

Need More Help with Unleashing the Power of Conflict?The Conflict Thesaurus: A Writer���s Guide to Obstacles, Adversaries, and Inner Struggles Volume 1 & 2 are packed with ideas on how to make conflict work harder in your story. Find out more.

The post Does Your Story Need a Hit of Organic Conflict? Look to Your Setting. appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

March 27, 2023

How to Uncover Your Character’s Deepest Fear

Fear is a disruptive force, even though its job is to keep us safe. When there’s a perceived physical or psychological threat, our brain blasts us with a shot of adrenaline so we respond, fight, flight, or freeze, whichever helps us navigate the danger we’re in.

But fear is also insidious. It can sink into our thoughts and memories and become an ongoing dark force that cloaks us, changing our behavior and how we see the world.

We become ever-watchful for new threats, and avoid things that have the potential to lead to another painful experience. In fiction, characters will also feel this dark weight, and it can be as detrimental to them as it is to us.

Fear may cause a character to…Hold back in relationships

Underachieve (by choosing ‘safe’ goals below their potential)

Avoid certain places, events, and people

Misread situations and overestimate threats

Feel stuck in life

Struggle with self-worth

Retreat into themselves

Stay within their comfort zone

Settle for less

Find it harder to make decisions

Hold onto the past in an unhealthy way

Have a more negative view of the world

Doom cast (decide something will fail without trying)

Become triggered by certain events and circumstances

Project fears onto others (damaging relationships)

Develop phobias

Not take advantage of opportunities

Have unmet needs (that grow deeper as time goes on)

Develop health conditions

And more.

Strong characters have agency, meaning they make choices and act, steering their own path toward their goal. But this goal will be hard to achieve, and if fear is in the driver’s seat, it affects their choices and actions.

If they stay within their comfort zone rather than take a risk, avoid something they must do because they don’t want to be judged, or convince themselves an effort will only end in failure, their decisions and actions are impaired, and whatever they choose to do instead won’t be enough to win.

There are many debilitating fears which can hold someone back. Knowing what your character’s exact fear is, be it rejection, intimacy, competition, or something else, will help you write their actions, behaviors, and decisions in the story. It will also help you plot events to purposely challenge that fear, in the hopes that they will grow and come to control it, rather than it controlling them.

How to find your character’s deepest fearFears can be learned (like a child who fears dogs from being exposed to their mother’s phobia of them), but for the most part, fears are born of negative experiences, especially trauma.

For example, being surrendered to the state by a parent who no longer wants to be tied down would be a devastating experience for a character. This trauma likely would create a fear of rejection, abandonment, or both. They will move through life worrying that if they let someone in, that person will eventually get tired of them and the character will be discarded once again.

To find your character’s fear, think about their experiences, especially emotional wounds. What happened to them, and how did this shatter how they see themselves and the world? What insecurities do they now have? What triggers them, what do they avoid more than anything, and what do they refuse to do because the mental barrier of fear is too strong?

Help for brainstorming a character’s fears

We’re thrilled to announce that our Fear Thesaurus is now part of our THESAURUS descriptive database at One Stop for Writers.

This thesaurus dives into deep-level fears so you can show how one changes who your character is & how it steers their thoughts and actions in the story.

Each entry looks at what the fear looks like, the behavioral fallout it leads to, what might have caused it to form, the inner struggles your character may be facing as a result, and the triggers, possible disruptions to their life, and more.

Use this thesaurus to build deeper characters, understand the role of fear in character arc, and plot events that will be specifically challenging for your character so they struggle but also have an opportunity to grow!

Want to check the Fear Thesaurus out?Start a free trial, or use this one-time discount code:

FEARS

to save 25% off any plan.

(Valid until April 10th.)

1) To redeem, sign up or sign in

2) Go to Account >> My Subscription and choose your plan

3) Add & activate the FEARS ode in the box provided

4) Enter payment details, click the terms box, & hit subscribe

One Stop for Writers�� is a site Becca and I created to help you beyond our thesaurus books. It’s packed with tools designed to make planning, writing, and revising easier, and teach you to become a stronger storyteller as you go.

If you’d like to take a look, join Becca for a tour.

We hope you love this new addition. Happy writing!

The post How to Uncover Your Character’s Deepest Fear appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

March 23, 2023

Creative Ways to Brainstorm Story Ideas

Inspiration is a fickle beast. She strikes at inopportune times (3 AM, anyone?) then disappears for months on end. She doesn’t call, she doesn’t write. Or maybe she treats you differently, pouring on so many ideas that you can’t tell the golden nuggets from the stinky ones.

Finding and prioritizing story options can be a frustrating process, but it’s easier if you approach it from the right angle. Here are a few possible starting points.

Start with GenreWhat do you like to write? What do you like to read? Which kinds of stories are you passionate about? We know that emotions are transferable, from author to page to reader, so writing something that gets you excited pays off in dividends.

Do you like fantasy? Which elements? Think dragons, portals, evil wizards, shapeshifters���then consider how those elements might be reimagined.

Anne McCaffrey’s Dragonriders of Pern series gave us a whole new take on dragons, turning them from marauding villains into loving creatures that impress upon humans at birth and use their fiery powers for good.

Then, twenty years after the first book was published, she released the dragons’ origin story and how humans first came to Pern. While the previous books were straight fantasy, this one was also science fiction, showing the settlers traveling to the new world and using their technology to establish communities and bioengineer full-blown dragons from foot-long fire lizards. Dragonsdawn is an innovative blending of the sci-fi and fantasy genres in a way that was new and entirely fresh.

So think of the genre you want to write, then tweak the standard conventions to create something new. Or blend your preferred genre with another one and see what ideas come to mind.

Start with CharacterEveryone’s process is different. It’s one of the things I love about the writing community���the vast diversity of thought and method that can birth uncountable stories. Maybe you’re the kind of writer who’s drawn to characters. They come to you fully-formed, or you have an inkling of who they are before you have any idea what the story’s about.

If this is you, start by getting to know that character. If you have a good idea of their personality, dig into their backstory to see what could have happened to make them the way they are. If you already know about their troubled past, use that to figure out which positive attributes, flaws, fears, quirks, and habits they now exhibit. What inner need do they have (and why)? Which story goal might they embrace as a way of filling that void?

Characters drive the story, so they can be a good jumping-off point for finding your next big idea.

BONUS TIP: For an easy-to-use, comprehensive tool to build your character from scratch, check out our Character Builder .

Start with a Story Seed

But maybe it’s not characters that rev your engine. When I’m exploring a new project, I have no idea about the people involved. Instead, my stories typically start with a What if? question. What if a man abandoned his family to strike it rich in the California Gold Rush���what would happen to them? What if all the children under the age of 16 abruptly disappeared? What if someone’s sneezes transported them to weird new worlds?

If story elements, plotlines, and unusual events get your wheels turning, brainstorm those areas. If inspiration strikes when you’re neck-deep in research for your current story, write down those potential nuggets. Use generators to explore concepts you wouldn’t come up with on your own. Keep a journal of any possible seeds for future stories so you have options.

Start with a LoglineIf you’ve got a vague idea of something you might want to write about, a great way to explore it is to create a logline���a one- or two-sentence pitch that explains what your story is about. Here’s an example you might recognize:

A small time boxer gets a once-in-a-lifetime chance to fight the heavyweight champ in a bout in which he strives to go the distance for his self-respect.

Writing a logline for a story idea enables you to flesh it out and experiment with its basic elements. The process of test-driving your idea with different protagonists, goals, conflicts, and stakes can turn a boring or already-done concept into an entirely new one that you can’t wait to write.

BONUS TIP: For more information on how to write a logline, see these posts at Writers Helping Writers and Screencraft .

Start with GMCDebra Dixon’s Goal, Motivation, and Conflict (affiliate link) teaches authors how to use these foundational elements to plan and enhance a story. But the same principles apply to fleshing out a story idea. If you’re thinking about a certain goal (it’s a story about someone who has to stop a killer/find their purpose/plan a wedding), play with various conflicts and motivations. Throw ideas into the hopper and see what pops out. Keep turning the handle to produce concept after concept until one of them strikes your fancy.

Listen, we all know the importance of writing what we’re excited about. Without that passion, writing becomes a slog and our stories end up partially finished on a back-up hard drive instead of filling people’s bookshelves. So when it comes to story ideas, let your imagination run riot. Consider all the options, no matter how far out they are or uncomfortable they make you feel. Don’t stop ’til you find the one that gets you going.

Then get going.

BONUS TIP: For a comprehensive guide on brainstorming ideas and planning your story (as well how to draft and revise it), check out the One Stop for Writers’ Storyteller’s Roadmap .

The post Creative Ways to Brainstorm Story Ideas appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

Writers Helping Writers

- Angela Ackerman's profile

- 1022 followers