Angela Ackerman's Blog: Writers Helping Writers, page 24

April 2, 2024

Why Writers Should Use Psychology In Their Storytelling

A writer���s job is to do one thing well: pull the reader in. Our words should act like a tractor beam, sucking them into our story���s world. We tap into the reader’s emotions, seize their attention, and suddenly they forget to mow the lawn, eat cereal for dinner, and postpone bedtime yet again.

It’s glorious. So…how do we do it? Psychology.

People are hardwired for stories. For one, they contain experiences that the primal part of the brain likes to mine for information to help with survival. But there are other reasons, too, like the chance to experience certain emotions that act as a release, and the sense of connection a person gets from discovering common ground with others…in this case, the characters.

This is psychology at work.

Certain psychological processes steer us, even though we may not realize it. They shape how we respond to life���s ups and downs, our behavior toward others and ourselves, influence the goals we seek, and more.

Psychology is the study of mental processes and behavior to understand why people think and behave as they do.

Most of us aren’t experts in psychology. We may not even think much about the WHY behind our attitudes and behaviors. Nonetheless, psychological patterns and processes are whirring in the background, drawing from our personal beliefs, emotions, values, identity, and experiences to determine how we think, act, and behave.

Applying human psychology to characters makes them authentic and relatable to readers.Psychology is part of what it is to be human. Whether it’s a character’s struggles, choices, values, needs, or mistakes, readers can’t help but see a piece of themselves reflected in the character. A bond forms, and if we wish it, we can make that character important to them, someone whose hopes, desires, and goals are meaningful and worth cheering for.

We don’t need to be experts to use psychology, either. We may not always know the terminology or reasoning behind certain processes, but we know what they are like to experience. We can show a character struggling to mentally or emotionally process something and readers will relate���they���ve had to process challenging things, too. This familiarity creates connection and empathy, which is exactly what we want to happen.

Let’s look at a common psychological process: cognitive dissonance.

The best way to explain what this is will be to ask you a question: Have you ever experienced internal tension from an unsettling situation, like seeing a neighbor chain his dog up day after day?

Or maybe this tension crops up when you���re doing something you don���t feel 100% good about, like pulling into the McDonald’s drive-thru when you committed to making better choices and eating healthier.

If so, this tension is called cognitive dissonance, the psychological discomfort caused by contradicting thoughts, perceptions, values, or beliefs. It���s quite common ��� we all experience it. A few examples:

We discover information that challenges our current beliefs and sense of right and wrongWe must choose between competing values/beliefs because, in our current situation, we can’t live by bothWe are behaving in a way that doesn’t match with what we believe inCognitive dissonance causes uncomfortable emotions like confusion, worry, guilt, regret, or shame.

To illustrate, let’s go back to the McDonald���s example. Despite your plan to stick to healthy options, it’s been a hellish week, and you pull into the drive-thru. You feel guilty as you order, but when the food arrives, you park the car and indulge���it���s so good! Unfortunately, your Big Mac euphoria lasts only as long as the burger does, and now you���re regretting the decision to cave to your craving. Worse, you���re mentally beating yourself up for not having the willpower to resist.

Cognitive dissonance is powering this discord because you (a) like eating Big Macs but (b) want to lose weight and be healthy. You resolved inner tension briefly by choosing Team Big Mac, but because this behavior didn���t line up with that internal commitment you made to yourself, guilt and regret followed.

This is a psychological process so common readers will pick up on it in the story. The best part? Even if a character experiences dissonance and makes a choice that the reader would not, they still empathize with the character’s experience of internal strain.

Another form of internal contradiction is emotional dissonance. This happens when a person fakes an emotion that they don’t feel.

Can I use you as an example again? Let���s imagine at work you find yourself faking enthusiasm about your boss���s terrible marketing strategy. After all, you know from experience that he won���t listen to contrary opinions, and because you���re a team player, you put on your rah-rah face like everyone else in the meeting.

In this case, your dissonance is mild. You���ve weathered his bad ideas before and aren���t invested enough to state how you really feel.

But emotional dissonance isn���t always minor. Sometimes the emotion you���d have to fake is so far from what you feel that it clashes with your values or personal identity. Acting in alignment with an untrue emotion can mean sacrificing your belief system and going against who you are.

Let���s up the ante. You discover this marketing strategy is driven by a closely guarded secret: the company needs to dump a supply of expired baby formula that they’ve repackaged with fresh dates. When you confront your sales manager she explains that the product is fine, this happens all the time, so keep quiet and get out there and sell, sell, sell.

Can you, knowing the formula could be contaminated? Will you be able to fake confidence as you hit up those neonatal units and pharmacies to convince people to buy your product? Or is this something you can���t do because it crosses a line and violates your core values, regardless of how badly you need the bonus for meeting your sales quota?

Here, the divide between your true feelings (contempt and shock) and the emotion you���d need to fake (confidence) is much wider. Whichever you express reveals your identity: Are you the sort of person who does what���s right or what makes money?

Everyone protects their self-perceptions���things they believe to be true about themselves. Emotional dissonance in a story raises the stakes by challenging the character���s view of themselves, creating confusion, uncertainty, or regret. These difficult emotions are another point of common ground with readers because at one time or another, everyone has reflected on their own identity and whether they are being true to themselves.

Internal dissonance is the heart of inner conflict.Showing a character wrestle with clashing beliefs, values, or other inconsistencies, no matter what they are, will resonate with readers. The character’s situation may be new to the reader, but the internal tug of war is something they have experience with.

In short, psychology is awesome. Use it!

In short, psychology is awesome. Use it!If you’d like to know more (and discover the best way to encourage internal tension), watch for our upcoming guide, The Emotion Amplifier Thesaurus: A Writer���s Guide to Character Stress and Volatility.

This companion to The Emotion Thesaurus releases May 13th.

The post Why Writers Should Use Psychology In Their Storytelling appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

March 30, 2024

Character Type & Trope Thesaurus: Jock

In 1959, Carl Jung first popularized the idea of archetypes���”universal images that have existed since the remotest times.” He posited that every person is a blend of these 12 basic personalities. Ever since then, authors have been applying this idea to fictional characters, combining the different archetypes to come up with interesting new versions. The result is a sizable pool of character tropes that we see from one story to another.

Archetypes and tropes are popular storytelling elements because of their familiarity. Upon seeing them, readers know immediately who they’re dealing with and what role the nerd, dark lord, femme fatale, or monster hunter will play. As authors, we need to recognize the commonalities for each trope so we can write them in a recognizable way and create a rudimentary sketch for any character we want to create.

But when it comes to characters, no one wants just a sketch; we want a vibrant and striking cast full of color, depth, and contrast. Diving deeper into character creation is especially important when starting with tropes because the blessing of their familiarity is also a curse; without differentiation, the characters begin to look the same from story to story.

But no more. The Character Type and Trope Thesaurus allows you to outline the foundational elements of each trope while also exploring how to individualize them. In this way, you’ll be able to use historically tried-and-true character types to create a cast for your story that is anything but traditional.

DESCRIPTION: Athletically gifted, jocks live for their sport and are often popular because of their talents and accomplishments. A staple of Young Adult stories, these characters are often cast as heroes, antagonists, and love interests. As supporting or minor characters, they���re frequently portrayed in a negative light, as unintelligent, one-dimensional, cruel, or predatory.

FICTIONAL EXAMPLES: Cedric Diggory (the Harry Potter series), Andrew Clark (The Breakfast Club), AC Slater (Saved by the Bell), Oz (American Pie)

COMMON STRENGTHS: Alert, Ambitious, Confident, Decisive, Disciplined, Enthusiastic, Extroverted, Focused, Friendly, Inspirational, Passionate, Persistent, Playful, Protective, Simple, Spontaneous, Talented

COMMON WEAKNESSES: ��Cocky, Confrontational, Fanatical, Impatient, Impulsive, Irresponsible, Macho, Obsessive, Pushy, Reckless, Rowdy, Self-Indulgent, Superstitious, Unintelligent, Vain, Volatile

ASSOCIATED ACTIONS, BEHAVIORS, AND TENDENCIES

Being gifted in one or more sports

Being confident in social situations

Working out and exercising religiously

Working well on a team

Listening to their coach (but not necessarily to other authority figures)

Being disciplined

Watching their diet

Their identity being tied to their athletic ability and accomplishments

Being susceptible to peer pressure

Using athletic accomplishments to compensate for a perceived weakness

SITUATIONS THAT WILL CHALLENGE THEM

Being stuck on a losing team

No longer being able to perform due to an injury, disease, the natural effects of aging, etc.

Moving to a location where their preferred sport isn���t offered

Being pressured by an authority figure to perform well

TWIST THIS TROPE WITH A CHARACTER WHO���

Is multi-dimensional in their personality

Is an adult (not a teen)

Has an atypical trait: Humble, Philosophical, Studious, Whiny, Worrywart, etc.

CLICH��S TO BE AWARE OF

Dumb, muscle-bound jocks

The bullying jock who rules the roost and picks on weaker people

Other Type and Trope Thesaurus entries can be found here.

Need More Descriptive Help?

Need More Descriptive Help?While this thesaurus is still being developed, the rest of our descriptive collection (16 unique thesauri and growing) is accessible through the One Stop for Writers THESAURUS database.

If you like, swing by and check out the video walkthrough for this site, and then give our Free Trial a spin.

The post Character Type & Trope Thesaurus: Jock appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

March 28, 2024

Do You Need a Prologue? Take the Test!

By Julie Artz

Affiliate links below

After nearly ten years working with writers, I���ve decided the only inviolable rule in writing is that a romance must have either a happily ever after (HEA) or a happy for now (HFN) ending. And yet blog posts like these are full of writing ���rules.��� I loved Jami Gold���s post on rule breaking in fiction right here on Writers Helping Writers. Today I���d like to talk about one of the first rules she mentioned: Avoid Prologues.

Most writers recognize one of the most famous prologues in English-language literature, William Shakespeare���s sonnet opener in Romeo and Juliet that begins ���Two households, both alike in dignity, In fair Verona where we lay our scene…���

But at the same time, you���ve probably been told in a blog post, a conference talk, or writing course to avoid prologues at all costs. I���ve certainly cautioned many a writer against including a prologue. And 75% of the time it���s good advice, because prologues are often catch-all repositories for info-dump, world-building deep-dives, and spoilers. When a prologue works, though, it adds so much to your story. Here���s a checklist you can use to make sure your prologue is strong enough to break the ���no prologue��� rule:

Does it Pass the Prologue Test?Does the prologue you have planned:

Provide a hook that will leave the reader wanting more? This can be a mystery, a unique speculative element, a shocking/cliffhanger event, foreshadowing, or a gripping voice. See ���The Importance of a Great Opening��� by Lucy V. Hay for more on the hook.Foreshadow something that you couldn���t achieve via the main character���s point of view? See ���No, Don���t Tell Me��� by Jami Gold for more on foreshadowing.Introduce speculative elements in a story that starts in an otherwise contemporary or historical world? This can help you ensure you���re making the right promise to your reader.Introduce a mystery element or a question that the main character(s) might not be able to convey to the reader? Set up questions the reader will have to puzzle out as they read and you���ll have them turning pages into the wee hours of the night.Avoid cliche openings? Even in a prologue, you can���t start with a dream, a character looking in the mirror, or the classic dark and stormy night.Keep it short? No info-dump or onerous world-building. You don���t want the reader to be disappointed to learn the first voice they encounter in the story goes away after a short opening chapter, so give them just enough and move on to the main POV character in Chapter One.Prove itself absolutely essential to your story? If you can cut it and the story still holds water, you probably should. Make an agent/editor/reader feel that the prologue is crucial and they���ll love it as much as you do.If your prologue doesn���t tick any of the boxes above, don���t just rename your prologue ���Chapter One��� and assume you don���t have to worry about it. If it���s a different POV character, a vastly different time, or sometimes even a different setting, it���s probably still a prologue. And that���s OK, as long as you avoid the pitfalls discussed here. Now that you know the elements of a strong prologue, you know what to do to make yours better. And if you���re still struggling, I���ve included some great examples below for further study.

Three Examples of Prologues that WorkLearning to read like a writer is one of the cheapest, most self-directed ways to improve your writing. Examining these three prologues with a writer���s eye will help you peek behind the curtain and think about what makes them work. Then you can go apply what you���ve learned to your own prologue. For more exercises to learn how to read like a writer, get my free workbook here.

Spoiler Alert: The prologue examples I���ve provided below are, by definition, only the opening few pages of lengthy novels, but there are some spoilers below. Understanding why a prologue works includes not only thinking about the opening of the story, but the prologue���s function in relation to the later events of the book. If you have not read one of these stories and don���t want spoilers, skip to the other two examples.

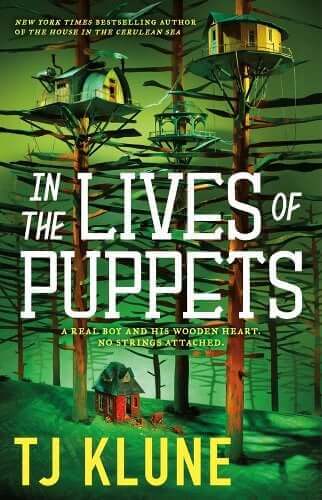

In the Lives of Puppets by TJ Klune

A Pinnocchio retelling set in a post-apocalyptic future, In the Lives of Puppets tells the story of young Vic and the mystery he kicks off when he brings a new robotic friend home from the junk heap. The prologue is from Vic���s father���s point of view and shows both how they ended up living alone in an isolated set of tree houses in the forest and how he came to adopt Vic. It immediately establishes the lonely father���s deep love of his new charge, which creates reader sympathy, and the fact that someone very bad is after Vic, which creates tension and mystery. But, and here���s the kicker, it also contains a lie that is the lynch pin of the mystery. Neither Vic nor the reader discovers the lie until the end of the book and that tension packs an extra gut-punch into an already wonderful story.

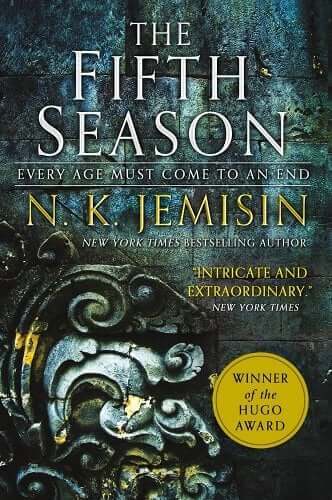

The Fifth Season by NK Jemisin

I don���t know this for sure, but I bet at least one person told NK Jemisin to cut not only her prologue, but the entire 2nd person point of view the prologue sets up in the first book in her stunning Broken Earth trilogy, The Fifth Season. Talk about a rule-breaker!

Jemisin���s world-building is second to none, but it���s also extremely complex. The prologue draws the reader in by beginning with the personal���the story of a mother losing her young child. Then she brilliantly addresses the reader with ���You need context��� and goes on to deftly, but briefly, paint a picture of the fantasy world. She continues to be the exception that proves the rule as she zooms out and takes on a more omniscient POV, introducing the reader to several important characters, the concept of ���stone eaters,��� which is central to the conflict, and ends with the apocryphal ���This is the way the world ends. For the last time.��� Chills! This rule-breaking prologue works because of the tension, mystery, and voice.

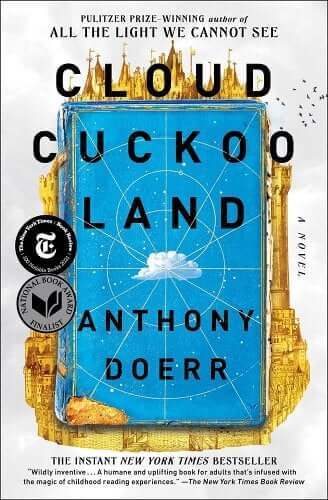

Cloud Cuckoo Land by Anthony Doerr

Like In the Lives of Puppets, this prologue includes a misdirection that isn���t revealed to the reader (or the POV character, Konstance) until late in this mind-bending, multi-timeline, multi-POV novel by Anthony Doerr. This prologue is shorter than the other two examples, but makes excellent use of introducing mystery elements. It introduces some of the key threads that will be explored in the story���the Diogenes, the siege of Constantinople, and also poses a question���why is this 14 year old girl alone in a spaceship? The reader doesn���t know how all these pieces come together, but they���re curious enough to read on, even though the ultimate mystery of Konstance���s story isn���t revealed until the very end.

For more information on a Prologue Done Right, check out Becca Puglisi���s post by that name, which deep dives into the prologue of Ruta Sepetys���s Between Shades of Gray.

Do you have a favorite prologue? I���d love to hear about it in the comments.

Julie Artz spent her���young life sneaking into wardrobes searching for Narnia. When people started to think that was too weird, she went in search of other ways to go on magical adventures. Now she finds those long-sought doors to mystical story worlds in her work as an author, editor, and book coach. She helps social and environmental justice minded writers slay their doubt demons so they can send their work out into the world with confidence. Her clients have published with the Big Five, with small and university presses, and indie/hybrid as well. An active member of the writing community, she has volunteered for SCBWI, TeenPit, and Pitch Wars and is a member of the EFA, the Authors Guild, and AWP. A consummate story geek and wyrdo, Julie lives in an enchanted forest outside of Redmond, Washington. Julie���s stories have been published in Crow Toes Weekly, the Sirens Benefit Anthology Villains & Vengeance, and the speculative anthology Beyond the Latch and Lever. Subscribe to Julie���s weekly newsletter, Wyrd Words Weekly, or connect with her below:

Facebook | Instagram | YouTube | Substack | Bluesky

The post Do You Need a Prologue? Take the Test! appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

March 26, 2024

Write Like a Magician: Creating the Illusion of an Unseen Character

Whenever we write a protagonist who lost someone important within their backstory, we have some heavy lifting ahead of us. That ���unseen��� character���a character who has died or who is simply away for one reason or another���is going to need to be developed and brought to the page somehow to deepen the emotion beneath the protagonist���s loss.

It won���t be enough that we tell the reader our character misses that person, or how that we label how the unseen character used to make the protagonist feel���good or bad. That sort of writing reduces the relationship down to what we call ���emotional abstraction������outright naming the way someone feels, rather than letting the reader experience the emotion in a firsthand way.

If the loss or separation is truly crucial to the story of your protagonist, you���ll want to create the illusion of the unseen character so it���s as if we���ve actually met them.

To better understand why developing an unseen character is worth the work, let���s look at an example based on emotional abstraction. The protagonist (Lila) has recently lost her father, and is reflecting on a memory:

Lila was happy every time she and Dad rode in his truck together.

In this example, the writer tells us Lila was happy in an outright way. Though you���d think this would be enough for us to know what she���s lost in losing her dad, it winds up falling flat. The reader knows how they should feel, but the head and the heart don���t quite connect. The difficulty with naming emotions���or emotional abstraction���is that reader doesn���t actually feel the emotion with any precision or depth. The word happy means different things to all of us, and so it���s a missed opportunity for the reader to know exactly how happy Dad made Lila. The happiness in this example isn���t Lila-shaped, or precisely Dad-induced.

Now, consider this example that seeks to avoid emotional abstraction by creating the illusion of Dad:

Lila couldn���t explain why she always preferred to sit right beside Dad whenever she rode with him in his truck. Maybe it was his warm shoulder swaying side to side alongside hers over each and every bump in the road. She never minded sitting on the big tear in the worn leather of the bench seat as long as she was next to Dad. He always gave Lila complete control of the radio, even if the music she chose made his face wrinkle up like he���d eaten a lemon. He kept a pair of drumsticks in the glove compartment so she could practice drumming on the dashboard as they made their way around town for their usual Saturday errands.

���Louder, Lils.��� He���d say every time they drove past the town library. She���d grin and he���d wink back.

Dad never learned how to play the drums. But Lila would focus on his rhythm as he thumped his palms the steering wheel, and try to sync her own beats with his.

Notice how in the second example, we accomplish so much more than the first example. We have a sensory-based memory with dialogue and body language that we can picture within our own minds. We feel how it feels for Lila to sit near Dad. We hear that cringey music Dad endures because Lila loves it, or the sounds made drumming along to the music. We can imagine the emotions they likely each feel with far more precision. We can better gauge his love for her, and who he was for her based on his actions. We can even judge the way she loves him back based on the way she tries to cover up his lack of rhythm by adjusting her own rhythm.

All of these details evoke an illusion that allows us to better comprehend and feel what it must be like for Lila to have lost Dad. We have unpacked ���happy,��� and we���ve given it precision and depth. We���ve made it Lila-shaped and Dad-induced.

In letting us indirectly meet an unseen character, we better understand both who they were as an individual and what their relationship with your front-story character/protagonist was like. As such, we better understand the emotions the protagonist is experiencing due to whatever has put distance between them and the unseen character.

If you have a character who isn���t technically in your front story but who is crucial to your protagonist���s backstory, you���ll want to consider creating the illusion of them on the page.

Let���s pull out our writerly magic wands and talk strategies for bringing an unseen character to life:Backstory/Flashback: As with the second example above, crafting vivid, punchy flashbacks that let us glimpse the relationship your protagonist had with the unseen character can be a powerful tool. Flashbacks are especially effective because they give you the chance to bring an unseen character onto the page despite their absence in your front story.Front-Story Objects: You can use objects to bring an unseen character to life. If we were to step into spaces they inhabited, or to go through their belongings, what would we learn about who they were? What objects does your protagonist hold onto that they were given from the unseen character? What mementos from time spent with that lost character does your protagonist keep? What can���t your protagonist bring themselves to get rid of? Which objects���wherever the protagonist goes���evoke memories?Front-Story Dialogue: What do other characters say about who the unseen character was? What do they not say about the unseen character? What does your protagonist say or not say about them? Are there characters your protagonist avoids ever since they lost the unseen character?Front-Story Locations: Where does your character avoid going because it���s a painful reminder of the lost character? Where does your character linger because they can���t let go of the unseen character?Front-Story Activities: What hobbies or activities does your character avoid because of losing the unseen character? Are there activities they���re especially fixated on since losing the unseen character? What are they losing out on in life because of the loss?Creating the illusion of the unseen character is only part of the heavy-lifting, though. We have to consider why we���ve chosen to include this lost character in your protagonist���s life in the first place, and how it relates to the journey ahead.

So much of what makes an off-the-page character work is what they do to challenge the protagonist in your front story.

Consider the following questions:What didn���t your character know about the lost character that your front story might reveal to them? How is losing that character holding your character back when we first meet them? What events might occur to provide your character aha moments about letting go? What plot points might reveal the truth about something the protagonist couldn���t see back when the other character was around?

How did losing that unseen character turn out to help your protagonist figure out what they needed all along? What is it about who your unseen character was that reveals your protagonist to us at each flashback point? What are we learning not just about the unseen character in a flashback, but about your protagonist? How do those flashbacks show us change in your protagonist? Does each flashback reveal something slightly different? Is there a truth that needs to be revealed?

Consider why this specific loss of another character in your protagonist���s backstory matters and how it relates to their needs in your front story. Why, in other words, is losing that unseen character a starting point in what your protagonist needs to do externally and how they need to grow internally? How might the unseen presence of a character slowly draw your protagonist in toward some sort of journey of discovery? How do the memories of the unseen character or new discoveries about who they were shift your protagonist? How do the memories ask them to face some sort of fear or inner truth they’ve been incapable of seeing���likely something about themselves���when the dust settles?

What type of unseen character is part of your protagonist���s backstory? How does the loss of that character give rise to the journey you have planned for your own book? Do you have favorite examples of books, movies, or films that feature an unseen character?

Happy writing!Marissa

The post Write Like a Magician: Creating the Illusion of an Unseen Character appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

March 23, 2024

Character Type & Trope Thesaurus: Reluctant Hero

In 1959, Carl Jung first popularized the idea of archetypes���”universal images that have existed since the remotest times.” He posited that every person is a blend of these 12 basic personalities. Ever since then, authors have been applying this idea to fictional characters, combining the different archetypes to come up with interesting new versions. The result is a sizable pool of character tropes that we see from one story to another.

Archetypes and tropes are popular storytelling elements because of their familiarity. Upon seeing them, readers know immediately who they’re dealing with and what role the nerd, dark lord, femme fatale, or monster hunter will play. As authors, we need to recognize the commonalities for each trope so we can write them in a recognizable way and create a rudimentary sketch for any character we want to create.

But when it comes to characters, no one wants just a sketch; we want a vibrant and striking cast full of color, depth, and contrast. Diving deeper into character creation is especially important when starting with tropes because the blessing of their familiarity is also a curse; without differentiation, the characters begin to look the same from story to story.

But no more. The Character Type and Trope Thesaurus allows you to outline the foundational elements of each trope while also exploring how to individualize them. In this way, you’ll be able to use historically tried-and-true character types to create a cast for your story that is anything but traditional.

DESCRIPTION: This protagonist doesn’t want to be a hero and actively works to avoid becoming one. Throughout the course of their arc, they eventually embrace and grow into their role as the hero of the story.

FICTIONAL EXAMPLES: Frodo Baggins (The Lord of the Rings franchise), Katniss Everdeen (The Hunger Games trilogy), Vianne Mauriac (The Nightingale), Han Solo (Star Wars: A New Hope), Sarah Connor (The Terminator)

COMMON STRENGTHS: Adaptable, Alert, Cautious, Courageous, Empathetic, Generous, Honorable, Humble, Independent, Introverted, Just, Loyal, Pensive, Resourceful, Responsible, Sensible, Talented

COMMON WEAKNESSES: Apathetic, Cowardly, Cynical, Evasive, Hostile, Indecisive, Nervous, Paranoid, Selfish, Stubborn, Suspicious, Timid, Uncooperative, Worrywart

ASSOCIATED ACTIONS, BEHAVIORS, AND TENDENCIES

Being self-reliant

Having high moral standards

Disliking being the center of attention

Enjoying solitude

Preferring to be seen as ordinary

Being self-serving or self-centered (initially)

Having a strong sense of justice

Tending toward skepticism

Having commitment issues

Underachieving

SITUATIONS THAT WILL CHALLENGE THEM

Having to decide to engage in a difficult situation or do nothing

A loved one facing mortal peril

The stakes becoming personal, making it harder for the character not to act

Others acknowledging the character’s weakness and pushing them to change

TWIST THIS TROPE WITH A CHARACTER WHO���

Has a good reason for their reluctance that goes beyond insecurity or selfishness

Has skeletons in their closet

Has an atypical trait: Flamboyant, Playful, Vindictive, Whiny, Witty, etc.

CLICH��S TO BE AWARE OF

The character making an abrupt reversal from reluctant to fully committed hero

The reluctant hero who takes on the hero mantle after their mentor or other key character is killed

Other Type and Trope Thesaurus entries can be found here.

Need More Descriptive Help?

Need More Descriptive Help?While this thesaurus is still being developed, the rest of our descriptive collection (16 unique thesauri and growing) is accessible through the One Stop for Writers THESAURUS database.

If you like, swing by and check out the video walkthrough for this site, and then give our Free Trial a spin.

The post Character Type & Trope Thesaurus: Reluctant Hero appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

March 20, 2024

Phenomenal First Pages Contest – Guest Editor Edition

Hey, wonderful

writerly people!

It���s time for Phenomenal First Pages, our monthly critique contest. So, if you need help with the beginning of your novel, today’s the day to enter for a chance to win professional feedback.

Six winners will receive feedback on their first five pages!Entering is easy. All you need to do is leave your contact information on this entry form (or click the graphic below). If you are a winner, we’ll notify you and explain how to send us your first page.

Contest DetailsThis is a 24-hour contest, so enter ASAP.Make sure your contact information on the

entry form

is correct. Six winners will be drawn. We will email you if you win and let you know how to submit. Please have your first five pages ready in case your name is selected. Format it with��1-inch margins, double-spaced, and 12pt Times New Roman font.��All genres are welcome except overtly religious books The editor you’ll be working with:Erica Converso

Contest DetailsThis is a 24-hour contest, so enter ASAP.Make sure your contact information on the

entry form

is correct. Six winners will be drawn. We will email you if you win and let you know how to submit. Please have your first five pages ready in case your name is selected. Format it with��1-inch margins, double-spaced, and 12pt Times New Roman font.��All genres are welcome except overtly religious books The editor you’ll be working with:Erica Converso

I���m Erica Converso, author of the Five Stones Pentalogy (affiliate link). I love chocolate, animals, anime, musicals, and lots and lots of books ��� though not necessarily in that order. In addition to my work as an author, I have been an intern at Marvel Comics, a college essay tutor, and a database and emerging technologies librarian. Between helping adult patrons in the reference section and mentoring teens in the evening reading programs, I was also the resident research expert for anyone requiring more in-depth information for a project.

As an editor, I aim to improve and polish your work to a professional level, while also teaching you to hone your craft and learn from previous mistakes. With every piece I edit, I see the author as both client and student. I believe that every manuscript presents an opportunity to grow as a writer, and a good editor should teach you about your strengths and weaknesses so that you can return to your writing more confident in your skills. Visit my website astrioncreative.com for more information on my books and editing and coaching services.

Sign Up for Notifications!If you���d like to be notified about our monthly Phenomenal First Pages contest, subscribe to blog notifications in this sidebar.

Good luck, everyone. We can’t wait to see who wins!

PS: To amp up your first page, grab our First Pages checklist from One Stop for Writers. For more help with story opening elements, visit this Mother Lode of First Page Resources.

The post Phenomenal First Pages Contest – Guest Editor Edition appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

March 19, 2024

The Secret To a Compelling Author Bio

Are you struggling to write the perfect author bio for your book, social media or website? Then this post is for you! Say goodbye to boring bios and hello to a profile that truly reflects who you are as a writer.

Let’s dive in and unlock the power of an unforgettable author bio … Let’s go!

Why Is an Author Bio Important?At grass roots level, an author bio is a brief summary of who you are and what you do as a writer. It may seem like just another piece of information to include on your book cover or website, but it holds much more significance than that.

In fact, it can be one of the most powerful tools in your writing career. As writers, our words are our brand. Our readers want to know more about the writer behind the stories they love. An author bio provides them with that insight!

A good author bio gives readers a glimpse into our background, interests, and accomplishments that have shaped us as writers. But why else is an author bio so important? Let’s delve deeper … A good bio:

Establishes credibility and trustworthinessConnects with readers on a personal levelProvides context for our workActs as a promotional toolUseful for our blogs, social media or other sites like LinkedIn or AmazonTip #1: Highlight your accomplishments and credentialsAs a writer, it can be daunting to condense one’s entire writing career or creative journey into a short author bio. Our author bio is often the first introduction readers have to us and our writing, so it’s crucial to make a strong impression.

One effective way to make your author bio compelling is by highlighting your accomplishments and credentials. This step involves showcasing any notable achievements or milestones in your writing career as well as mentioning relevant educational background or experience.

Here are some examples of impressive accomplishments that you could consider including in your author bio:

Published WorksAwards and RecognitionsBestseller StatusSpeaking EngagementsSuccessful Book LaunchesMedia FeaturesPositive Reviews from professionals in your genreRemember, the key is to only include accomplishments that are relevant to your writing career and demonstrate your skills. Including too many vague or unrelated achievements can dilute the impact of those that truly matter. Choose a few of your most impressive accomplishments and highlight them with specific details, rather than listing out every single one.

Tip #2: Add a Personal Touch and Show Your PersonalityYour author bio is the perfect opportunity to showcase your unique voice and personality. It’s not just a dry list of credentials, but a chance for readers to get to know you on a deeper level.

Adding a personal touch to your bio can make it more engaging and memorable for potential readers … but don’t go overboard, because that might make you seem obnoxious or hard to work with. The whole point of your bio is to get your name out there in GOOD way!

Want to see an example of a more light-hearted bio? Then check out MY INSTAGRAM AUTHOR BIO.

Tip #3: Keep it concise and relevantWhen it comes to writing your author bio, one of the most important tips to keep in mind is to make sure it is concise and relevant. As writers, we often have a lot to say about ourselves and our work, but it’s important to remember that a long and rambling bio can quickly lose the attention of readers.

So how do you balance providing enough information while keeping your bio short and sweet? First up, start by identifying what information is essential for your audience to know about you.

Next, think about what makes you stand out as a writer. What sets you apart from others in your field?

If you want to see a bio that focuses only on professional accomplishments, check out MINE HERE ON LINKEDIN.

By the Way …Again – as tempting as it may be to list everything in your author bio, try not to overwhelm readers with too much detail! Instead, select a few key accomplishments that demonstrate your expertise and credibility as an author. And don’t forget ��� always keep these accomplishments relevant to those reading your bio.

Remember that brevity does not mean sacrificing quality. Your bio should still be well-written and professionally presented. Use complete sentences and proper grammar. Avoid slang or overly casual language unless it aligns with your brand or writing style.

BONUS: How Long Should an Author Bio Be?When it comes to creating a compelling author bio, one crucial aspect that writers often overlook is word count. Many authors either provide too little information or go overboard and include excessive details. However, finding the right balance and sticking to an appropriate length can have a significant impact on how readers perceive you as an author.

So, what is the ideal length for an author bio? If on social media, you may have only a few characters to play with, so limit yourself to how much space you are given. Simple as that!

In other places, you will have more space. While there isn’t a set standard, most experts recommend keeping it concise and between 100-200 words. This may seem like a small word count, but it’s enough to convey your essential information without losing the reader’s interest.

One of the main reasons for keeping your author bio short is that it allows you to focus on highlighting only the most relevant details about yourself. Remember, readers are more interested in learning about your writing achievements and background rather than your personal life story.

Last Points

Last PointsSo, when crafting your author bio keep in mind …

Brevity is keyDon’t sacrifice important information in the process!Stick to 100-200 wordsMake every word countFocus on highlighting writing achievements andAlso any relevant backgroundConcentrate on the above and you’ll create a compelling author bio that will captivate readers and leave a lasting impression.

Good Luck!��The post The Secret To a Compelling Author Bio appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

March 16, 2024

Character Type & Trope Thesaurus: Adrenaline Junkie

In 1959, Carl Jung first popularized the idea of archetypes���”universal images that have existed since the remotest times.” He posited that every person is a blend of these 12 basic personalities. Ever since then, authors have been applying this idea to fictional characters, combining the different archetypes to come up with interesting new versions. The result is a sizable pool of character tropes that we see from one story to another.

Archetypes and tropes are popular storytelling elements because of their familiarity. Upon seeing them, readers know immediately who they’re dealing with and what role the nerd, dark lord, femme fatale, or monster hunter will play. As authors, we need to recognize the commonalities for each trope so we can write them in a recognizable way and create a rudimentary sketch for any character we want to create.

But when it comes to characters, no one wants just a sketch; we want a vibrant and striking cast full of color, depth, and contrast. Diving deeper into character creation is especially important when starting with tropes because the blessing of their familiarity is also a curse; without differentiation, the characters begin to look the same from story to story.

But no more. The Character Type and Trope Thesaurus allows you to outline the foundational elements of each trope while also exploring how to individualize them. In this way, you’ll be able to use historically tried-and-true character types to create a cast for your story that is anything but traditional.

DESCRIPTION: This character is driven by a need for stimulation and excitement. The more intense or dangerous the situation is, the more likely they are to participate.

FICTIONAL EXAMPLES: Ethan Hunt (Mission Impossible), Han Solo (Star Wars: A New Hope), James Bond (the Ian Fleming series), Odysseus (The Odyssey), Maverick (Top Gun)

COMMON STRENGTHS: Adaptable, Adventurous, Alert, Bold, Confident, Courageous, Creative, Curious, Decisive, Focused, Imaginative, Independent, Industrious, Inspirational, Intelligent, Observant, Passionate, Perceptive, Persistent, Quirky, Resourceful, Spontaneous, Spunky, Uninhibited

COMMON WEAKNESSES: Addictive, Cocky, Impatient, Impulsive, Irresponsible, Macho, Mischievous, Obsessive, Rebellious, Reckless, Self-Destructive, Stubborn

ASSOCIATED ACTIONS, BEHAVIORS, AND TENDENCIES

Seeking out risky activities

Looking for excitement

Believing anything is possible

Competitiveness

Being highly independent

Underestimating danger

Spontaneity

Believing the rules don’t apply to them���e.g., bad things happen to other people, not them

Impulsivity

Struggling with organization, finances, time management, and other detail-oriented tasks

SITUATIONS THAT WILL CHALLENGE THEM

Scenarios where there are many rules to be followed

Situations that require conformity (such as working in the military or a bureaucracy)

Living in suburbia and being stuck in a 9 to 5 desk job

Being forced to work with a group

TWIST THIS TROPE WITH A CHARACTER WHO���

Has an unconventional skill or hobby, such as dancing or studying philosophy

Likes to be part of a group

Has an atypical trait: Inflexible, cooperative, insecure, indecisive, whiny, needy, meticulous, etc.

CLICH��S TO BE AWARE OF

The thrill-seeker who is the only one in the group who never gets shot or wounded

An adrenaline junkie who’s always on and never needs any downtime

A thrill-seeker who isn’t afraid of anything

Other Type and Trope Thesaurus entries can be found here.

Need More Descriptive Help?

Need More Descriptive Help?While this thesaurus is still being developed, the rest of our descriptive collection (16 unique thesauri and growing) is accessible through the One Stop for Writers THESAURUS database.

If you like, swing by and check out the video walkthrough for this site, and then give our Free Trial a spin.

The post Character Type & Trope Thesaurus: Adrenaline Junkie appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

March 13, 2024

The Emotion Amplifier Thesaurus (May 2024 Release)

We’re adding to our Thesaurus family!

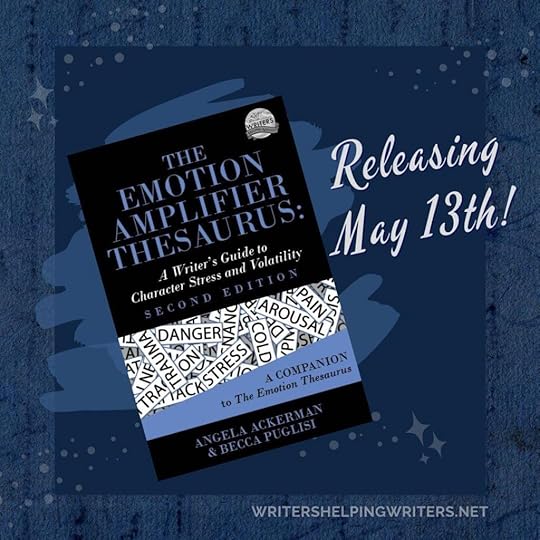

It’s been a while since our last book as we needed to recalibrate our release schedule from fall to spring (resulting in a year gap), but now we’re back in the thesaurus-making saddle. May 13th is coming fast, so it’s time to dish some details about our next writing guide!

First up…the cover!

First up…the cover!As this is an upgraded second edition and companion to The Emotion Thesaurus, we wanted the style of the books to match. This book is now a true thesaurus, packed with incredible help to showcase your character’s emotional state and help readers feel closer to your characters. More on that in a minute.

Next, the back jacket.THE EMOTION AMPLIFIER THESAURUS:

A Writer’s Guide to Character Stress and Volatility

STRESS YOUR CHARACTERS TO THEIR LIMITS

Characters who are in control of their emotions rarely slip up, which makes for boring reading. To avoid that pitfall, channel your dark side and introduce stress that will make it harder for them to think clearly. Your weapon of choice? An amplifier. Pain, arousal, dehydration���conditions and states like these make it difficult for a character to emotionally self-regulate, setting them up for overreactions, misjudgments, and (hopefully) colossal mistakes they���ll have to fix and learn from.

Inside The Emotion Amplifier Thesaurus, you���ll find:

A deep dive into cognitive and emotional dissonance and how psychological discomfort steers a character���s reasoning and impacts their ability to make decisionsInformation on emotional stress as a trigger for self-awareness and personal growth, which makes amplifiers powerful levers to help steer story structure and character arcLists of body language cues, internal sensations, thoughts, and other descriptives to show the effects of more than 50 amplifiersBrainstorming help on how to use each amplifier to generate tension and complication, apply everyday pressure, and make a character emotionally volatileFifty-two bonus writing tips to help you wield amplifiers with skill and precision, taking your scenes from good to greatPush your characters. Give them no quarter. Use physical, cognitive, and psychological strain to force them to face their mistakes, acknowledge their true feelings, and work through the contradictions at the heart of every inner struggle.

How is this book a “companion” to The Emotion Thesaurus?

How is this book a “companion” to The Emotion Thesaurus?When we were building the original Emotion Thesaurus, writers would ask us to cover specific emotions only some were not feelings at all, rather more states of being that had the ability to disrupt and amplify whatever the character was feeling. So, we created a quick mini booklet in the same style as The Emotion Thesaurus for 15 states like Boredom, Pain, and Stress. Now, that mini-guide has been expanded to over 50 states and conditions that will challenge your character’s ability to control their emotions, and it is packed with knowledge on how to use them to create bigger emotional moments that readers will feel part of.

I have the original ebooklet. How is this guide different?Great question! Our original Emotion Amplifier ebooklet (45 pages) was a bare-bones guide, intended to provide quick help for describing common states like pain, illness, hunger, etc. that are often mistaken for emotions. It contained a brief how-to and 15 entries. This second edition (XXX pages) is a true deep dive into this storytelling element to show you exactly just how powerful amplifiers are. This guide shows you how to use them to destabilize a character’s emotions, generate conflict, support story structure, and most importantly, bring readers inside your character’s emotional experience using common human struggles and internal turmoil. We’ve expanded the thesaurus to cover over 50 amplifiers, and for the first time ever, each entry has three pages of brainstorming material, not two. Because emotion amplifiers are so versatile and perfect for unlocking a character’s psychological state to create intimacy with readers, we couldn’t contain our lists to two pages.

Will there be a preorder?Sorry, no. We’ve tried a preorder in the past, but a certain online store made a mess of it (costing us hundreds of sales), so we’d rather not have that happen again. But if you’d like a notification as soon as the book is out, add your email here.

Are you giving out ARCs?We do have 50 digital ARCs and as we do at every launch, draw names from our lovely Street Team who have expressed a desire to review the book whether they win an Arc or purchase the book. If you know you’ll be reviewing this guide one way or they other and would be interested in joining our Street Team, sign up here. We’ll draw the ARC winners in April.

Do you have a Street Team? Can I help?Yes, yes, and YES! If you want to join our Street Team, you can sign up here (and thank you!). We would love to have your help. Plus, being on the inside of a book launch means you can apply what we do to your own book launch strategy. Win-win!

Can I access The Emotion Amplifier Thesaurus at One Stop for Writers?

Yes! If you’d like to take a look at the list of amplifiers, you can find the Emotion Amplifier Thesaurus here. (If you’d like to poke around & view this powerful THESAURUS DATABASE in full, we recommend starting a 2-week free trial.)

Did we miss a question? If so, please ask, and we’ll be happy to answer!Thanks so much for always supporting us. May 13th will be here soon, and we can’t wait. We hope this book is everything you need and more!

Click here to be notified when this book releases.

The post The Emotion Amplifier Thesaurus (May 2024 Release) appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

March 12, 2024

Continuing a Series: Is This Info Too Repetitive?

We���ve probably seen advice warning that any time our story revisits information, we risk the idea feeling repetitive or redundant to readers if we���re not careful. Not surprisingly, the same risk can apply even across books in a series.

Yet when we write a book series, we usually need to repeat some information from book to book. Depending on the type of series, we might need to repeat character introduction or worldbuilding information, or we might need to touch on events from previous books, and so on. So how can we avoid the repetitive/redundant risk when presenting information in a book series?

Series 101: Types of SeriesTo understand our options for how to handle repeating information, we first need to determine the type of series we���re writing. In general, books are designated a series because they share at least one element:

Shared Setting: These series take place in the same ���world��� but each feature different point-of-view (POV) characters. The characters of book two may or may not have been introduced in book one. The events of book two may or may not be dependent on the events of book one.Shared Character(s): These series feature the same POV character(s). The events of book two may or may not be dependent on the events of book one.Shared Story Arc: These series follow a story arc over several book installments. Each book usually features at least some of the same characters. Sometimes a story will end with a cliffhanger to be resolved in the next book. These books need to be read in order.Which Category Best Fits Our Series?

We need to determine which category best fits our series, as the writing techniques that work best for handling repeated information vary for different types of series. For example, when series books are standalone, we use different techniques than when the books must be read in a certain order.

What if the books can make sense out of order but are connected enough to make events of one book affect the next book?

In this case, the series usually has less focus on the overall Shared Story Arc than the other shared elements, so the standalone techniques of the Shared Character or Shared Setting categories will likely be the most helpful to us. However, it���s also possible that that our series may change category near the end.

Some series can be read in any order until the last book(s), when the minor Shared Story Arc threads referenced throughout the series grow in importance to create a series-level story. For these series, to get the most out of the final book, readers should be familiar with the rest of the series first. In this situation, we can use the Shared Character/Setting techniques in the earlier books, and then when that Shared Story Arc finally takes over as the main focus of the book, we can change to use the Shared Story Arc techniques in the later book(s). We should just let readers know that they���ll get the most out of the last book(s) if they read the other books first.

Want to learn the Techniques for Series Based on Shared Setting

or the Techniques for Series Based on Shared Character?

Check out Jami���s companion post!

The most important aspect of Shared Story Arc series is that if we intend to write the books with an assumption that readers have read previous books, we need to include that information in our marketing materials. For example, our book description/back-cover blurb should mention that this is book number-whatever in our series, and readers should start at the beginning of the series.

So if readers will read the books in a certain order, does that mean we shouldn���t bother repeating information at all? Unlikely.

Even within a single book, we still need to give readers hints about small details they may have forgotten since the earlier reference. For example, we might mention how a minor character is related to the story if they haven���t been on the page for several chapters, such as using a tag like ���her brother.��� (She couldn���t go to George for help, as her brother still hadn���t forgiven her for the last catastrophe.)

With a series, there���s usually months or years between the releases of our series��� books, or even if we release the series in a bundle, readers might not binge them all at once. So just like our techniques within a single book, we often need to find ways to trigger readers��� memory of earlier information.

Assuming we���ve let readers know that it���s essential to start the series at the beginning, we can focus on repeating a minimal amount of information with these 3 techniques���

#1: Use Just Enough Information to Trigger Readers��� Memory

In standalone series, we need to share enough information to get new readers up to speed, and that means re-introducing characters, the story world, and treating previous events as backstory. However, in story-arc series, we can shortcut a lot of repeated information by sharing just enough to trigger readers��� memory.

For example, rather than re-establishing why our protagonist is estranged from their family, we might just allude to the fact that they���re estranged from them. Or rather than sharing paragraphs of explanation to introduce main characters or the setting/story world, we might just state aspects of characters and the story world as facts and avoid the feeling of a re-introduction. In other words, focus on facts not explanations.

This memory-triggering process may look like one of these options, depending on the importance of the details:

a short tag: her office nemesis,a sentence: She���d still never forgiven her coworker for stealing her idea, ora paragraph: She���d still never forgiven her coworker for stealing her idea. In fact, the more she���d thought about Andrew���s undeserved raise and promotion, the more upset she���d gotten. Soon, though, her plan for revenge would have its day.The more important a fact, such as a major aspect of the story, the more strongly we should trigger readers��� memory with essential details in case they can���t remember. Do readers need to know the protagonist is traumatized by her father���s death in the previous book? Share how that trauma is affecting her currently, and thus include the fact of the death event along the way, much as how we���d treat any backstory.

If we need more than a paragraph or two to share the necessary details of important information with returning readers, we can try the next suggestion to avoid repeating ourselves too much.

#2: Use Different Circumstances to Mention Repeated InformationFor important information, we need to ensure that readers remember enough that they���ll understand events. When our story requires us to repeat more than a condensed paragraph of information, we can avoid the feeling of too much repetition by changing the circumstances of our reveal.

For example, if we initially revealed the information in a shocking twist, a follow-up book may remind readers of the information via:

a dialogue exchange,a different character bringing it up,internal monologue,an exploration of the aftereffects,a traumatic flashback, orbeing part of a conflict, etc.Different techniques will fit best with different storytelling styles. The point is to change the circumstances so we���re forced to use different words, phrases, and descriptions to reduce the sense of d��j�� vu.

#3: Focus on How the Information Has ChangedIn addition, we can emphasize how any repeated information has changed over the story���s arc. Or if the information itself hasn���t changed, we can bring it up by mentioning how characters have changed their perspective about it.

For example, we may explore how the POV character feels about it, how skilled they are at dealing with it, how they plan on taking advantage of it, etc. Revisiting the repeated information with some type of update can be a great way to ensure the repetition isn���t redundant, as readers are learning something new.

Final Thoughts about Avoiding Repetition in SeriesWith the right writing techniques, we can avoid���or at least minimize���the issue of readers feeling a sense of d��j�� vu as we repeat information in our series. When we find ways to change the information or how we deliver that information, we ensure readers are learning something new or seeing the information through a different perspective, and that gives them a reason to keep reading. *smile*

Want to learn techniques for Shared Setting or Shared Character series? Visit my companion post!

Have you written a series and struggled with how to revisit information? Can you think of any other techniques we can use to avoid a sense of repetition or redundancy? Do you have any questions about these techniques or how to approach repeating information in a series?

The post Continuing a Series: Is This Info Too Repetitive? appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

Writers Helping Writers

- Angela Ackerman's profile

- 1022 followers