Angela Ackerman's Blog: Writers Helping Writers, page 129

January 14, 2017

Character Motivation Entry: Catching the Bad Guy/Girl

What does your character want? This is an important question to answer because it determines what your protagonist hopes to achieve by the story’s end. If the goal, or outer motivation, is written well, readers will identify fairly quickly what the overall story goal’s going to be and they’ll know what to root for. But how do you know what outer motivation to choose?

If you read enough books, you’ll see the same goals being used for different characters in new scenarios. Through this thesaurus, we’d like to explore these common outer motivations so you can see your options and what those goals might look like on a deeper level.

[image error]

Courtesy: Pixabay

Character’s Goal (Outer Motivation): Catching the Bad Guy/Girl

Forms This Might Take:

Catching a killer before he strikes again

Stopping the terrorist before his bomb goes off

Identifying a kidnapper so his victims can be freed

Catching a ring of car or bank thieves

Figuring out who’s running a trafficking ring

Finding the person responsible for someone’s murder

Stopping a serial killer or rapist

Identifying the leak in one’s department

Stopping a megalomaniac or cult leader from killing a large number of people

Figuring out who the double agent is and stopping him/her from selling secrets to the enemy

Stopping an assassin from completing his mission

Human Need Driving the Goal (Inner Motivation): safety and security

How the Character May Prepare for This Goal:

Traveling to places where the guilty party might be found

Enlisting like-minded people for his team

Gathering evidence

Interviewing witnesses and the victim’s family members and friends

Employing experts in their fields (profilers, private investigators, biographers, etc.)

Calling in favors for things that need to be done quickly

Going over an uncooperative boss’s head

Coming up with a short list of suspects

Inspecting associated crime scenes

Pouring over files, looking for connections

Putting together a timeline of events

Viewing all others with suspicion

Putting out fires along the way (defusing one of the terrorist’s bombs, saving an escaped victim, etc.)

Breaking the rules to get what one needs (breaking into someone’s apartment, ordering an illegal wiretap, roughing up a suspect for information)

Holding back information one doesn’t want to get out

Staking out a suspect’s home or place of business

Possible Sacrifices or Costs Associated With This Goal:

Losing the respect of one’s superiors when one goes against the chain of command

Slipping down the corporate or political ladder due to pissing off the wrong people

Strained family relations due to working long work hours

Becoming so obsessed with finding the perpetrator that one’s health suffers (eating poorly, not sleeping enough, etc.)

Getting emotionally or physically involved with a witness, suspect, or one’s partner, and ruining one’s personal relationships as a result

One’s family being threatened by the perpetrator or his cronies

Being injured or killed in the line of duty

Losing one’s job due to one’s obsession or an inability to follow rules and the chain of command

Becoming addicted to substances to help one keep going (caffeine, nicotine, sleeping pills, illegal drugs, alcohol, etc.)

Bankrupting oneself from personally financing the case

Making stupid mistakes due to fear, paranoia, pride, lack of sleep, acting hastily, etc. that results in lives being lost or people suffering

Roadblocks Which Could Prevent This Goal from Being Achieved:

The perpetrator himself

Those who want the perpetrator to remain free

Unreliable witnesses

Untrustworthy, unethical, or criminal co-workers

Political pressure being applied from higher up

Incompetent or lazy partners

Bureaucratic red tape

The hero’s personal demons (addiction, fatal flaws, doubts, fears, etc.)

The hero’s loved one ones who don’t want to see him hurt or who resent him putting the family at risk

Unhinged loved ones of the victim

Outdated or faulty equipment

Budgetary constraints

Emotional entanglements between the hero and people involved in the case

Talents & Skills That Will Help the Character Achieve This Goal:

A Knack for Languages

Good Listening Skills

Blending In

Gaining the Trust of Others

Enhanced Hearing

Knowledge of Explosives

Lying

Multitasking

Photographic Memory

Reading People

Self-Defense

Sharpshooting

Strategic Thinking

Swift-footedness

Possible Fallout For the Protagonist if This Goal Is Not Met:

People dying or being injured

A lack of confidence in himself

Extreme guilt and self-loathing

Losing his job

Being injured or losing his life

The perpetrator killing his loved ones

Other criminals are encouraged to continue taking advantage of others

Society feels less safe and more anxious

Grieving loved ones of the victim may try to take matters into their own hands through vigilantism

Clichés to Avoid:

The detective falling in love with the main suspect who he believes is innocent but is actually guilty

The police officer and her partner becoming sexually involved

The investigator’s boss being in on the plot and thwarting his efforts

Kick-butt characters (government agents, police officers, etc.) who are virtually indestructible

Click here for a list of our current entries for this thesaurus, along with a master post containing information on the individual fields.

Save

Save

January 10, 2017

Read More Fiction (A New Year’s Resolution for Writers)

Are we too late for New Year’s resolutions? I hope not, because there’s one I urge every writer to make.

Read more fiction.

It should be easy for us, right? Here, we’re all story lovers. But I mentor a lot of authors and you wouldn’t believe the number who tell me they make a deliberate point of not reading other fiction. I ask their reasons, and the answers have a certain logic:

They don’t want to be influenced by other writers or inadvertently copy an idea, character, or plot situation.

They need to spend the time writing because they’re struggling to fit enough hours in.

But when I’m critiquing their work, I frequently see problems that could be solved by studying the fiction of others. Here’s the short list of the usual suspects:

Boring Exposition. All stories need a lot of set-up, especially at the beginning. Too much and the reader wonders if you’ll ever get cracking with the action. Too little and the characters’ actions can look random and unbelievable. You’ve got a gigantic iceberg of background information and you have to figure out how much of it to show. The easiest way to learn this is to notice how it is done in other books. (For more tips on how to craft a powerful set-up, check out Becca’s recent post on the topic.)

[image error]

Courtesy: Pixabay

Failing to Give Readers What They Want. This comes down to questions of genre. Now I know a lot of us kick against the idea of categories. After all, we’re creatives. We don’t tick boxes; we invent the boxes. But all books have certain types of readers whose tastes fall into broad categories. I see a lot of writers who struggle to develop their plot events. Rather than just stab in the dark, it really helps to know the kind of thing your reader might be expecting. It might be a hint of mystery, the suggestion of a ghost, a focus on interiority, an emphasis on relationships, a sense of political pressures, a social issue, etc. Or they might want a bomb blast by page five. If we know what our readers enjoyed in other books, we can use our ideas to please them. And we’ll also spot what other ingredients we need to add.

Dialogue Issues. Many writers find this tricky. They either include no dialogue at all and write the entire book in their general narrative voice, or they switch gears completely and write dialogue scenes that are a list of who said what, with the narration disappearing altogether as though we have switched from a novel to a radio play. Or they might write scenes with too many characters. Movies can easily handle dialogue scenes with a lot of people, but in prose it’s hard to marshall them all in the reader’s mind. Of course, there are many novels that do all these things deliberately and successfully, but the writers are fully aware of the effects they are creating. My number one tip for authors struggling to make dialogue expressive and interesting is to read novels and notice how the dialogue is woven into the prose, how the speech and the description work together, how nuance and subtext are created.

Writing that Falls Flat. We want to know how to write so the reader is swept away. Prose in fiction is not just a set of explanations (John did this, then this, then this). Prose is the very texture of the experience. Your word choice creates the mood. Your sentence structure can quicken the reader’s pulse, or lull. Prose is music, lighting, aroma. It’s even something less definable that goes straight to our wiring. Look at this description by Graham Greene of the sound of a person being shot:

a thud like a gloved hand striking a door.

Not all fiction has to aspire to poetry, of course. But many writers are unaware of how much richness they could add if they used their prose sensitively. The best way to learn this is by reading.

We get writing lessons from everywhere!

Nowadays we have a lot of narrative media and we absorb lessons from them all, without even intending to. TV, films, music videos and adverts all use the power of story and are great for teaching us certain basics. From all these we can learn the essentials of structure: beginning, middle and end, how to use twists. They teach us how to create characters that will grab the reader’s attention and a piece of their heart. But some of the story essentials, such as dialogue, don’t translate to prose at all. And prose has certain unique qualities we can only learn from reading.

So this year, when you’re figuring out how to enhance your writing craft, make a little time to read fiction. Read books you like – and also books outside your comfort zone. Figure out what bores you, excites you, or sets your teeth on edge. You’ll learn just as much as you will from craft books. Give yourself a bit of pleasure – and improve your writing at the same time.

Roz published nearly a dozen novels and achieved sales of more than 4 million copies – and nobody saw her name because she was a ghostwriter. A writing coach, editor, and mentor for more than 20 years with award-winning authors among her clients, she has a book series for writers, Nail Your Novel, a blog, and teaches creative writing masterclasses for The Guardian newspaper in London. Find out more about Roz here and catch up with her on social media.

January 7, 2017

Character Motivation Entry: Seeking Out One’s Biological Roots

What does your character want? This is an important question to answer because it determines what your protagonist hopes to achieve by the story’s end. If the goal, or outer motivation, is written well, readers will identify fairly quickly what the overall story goal’s going to be and they’ll know what to root for. But how do you know what outer motivation to choose?

[image error]If you read enough books, you’ll see the same goals being used for different characters in new scenarios. Through this thesaurus, we’d like to explore these common outer motivations so you can see your options and what those goals might look like on a deeper level.

Character’s Goal (Outer Motivation): Seeking Out One’s Biological Roots

Forms This Might Take:

Tracking down one’s birth parents

Connecting with a half-sibling that one has just discovered

Returning to an orphanage in one’s country of origin in hopes of uncovering one’s past

Searching for the family one was kidnapped from

Trying to find biological relatives (if one’s birth parents were killed)

Seeking connection with maternal or paternal grandparents if one was abandoned by parents

Trying to find surviving family members long after a war or violent event scattered the family across the globe

Seeking out one’s relatives after being rescued as an child refugee by aid workers and taken elsewhere

Human Need Driving the Goal (Inner Motivation): love and belonging

How the Character May Prepare for This Goal:

Request access to one’s birth records (once one turns eighteen)

Ask one’s adoptive parents for details

Research the laws surrounding adoption at the time to understand the information hurdles ahead

Interview those involved in one’s adoption

Return to the city, town, and hospital where one was born and ask for records

Return to a foster home where one was before the adoption was finalized

Seek advice online from other adoptees in one’s situation (forums, support groups, websites)

Reach out to organizations that help adult children reconnect with birth families

Reach out to organizations that deal with refugee placement (if applicable)

Track down one’s family name if one knows it, searching for others with the same name

Get a job or put in extra hours to save up for a trip to return to one’s country of birth

Hire a lawyer to help facilitate access to one’s records (especially if they are in another country)

Look for police reports of local kidnappings, abuse or child abandonment (if this is a factor)

Hire a private investigator

Learn a foreign language or hire a translator (if there’s a language barrier)

Make a list of phone numbers and addresses of possible relatives to visit and interview

Start contacting possible leads and set up meetings if one is able

Possible Sacrifices or Costs Associated With This Goal:

Becoming obsessed to the point it strains relationships with one’s adopted family

Losing one’s job because one is always needing time off to travel and investigate leads

Losing one’s sense of self and identity as one digs deeper into one’s past

Friendships that become strained because one is no longer working to maintain them

Draining one’s finances to pay for information, travel, and professional services (lawyer, etc.)

Reopening old wounds of rejection and abandonment as one uncovers information that may be hard to take

Discovering a past history that is difficult (that one’s parent is a serial killer, that one was part of a human trafficking ring, etc.)

Roadblocks Which Could Prevent This Goal from Being Achieved:

Ineffective lawyers, investigators, and advocates

A fire or other disaster that destroyed one’s records

A lack of record keeping at the time (especially in the case of civil unrest)

Discovering the adoption was off the books and so documents are false

Discovering information that doesn’t mesh with what one’s parents were told

Language barriers

People who don’t want to talk for fear of repercussions

Finding relatives that are unhelpful (fearing inheritance issues, who are hurt by the discovery etc.)

Discovering leads have died because much time has passed

Discovering a cover up by the state because of some sort of wrongdoing

Running out of money for bribes (if needed)

Running into dangerous people determined to see one does not succeed (criminals, people involved in a past war crime, etc.)

Having to travel to dangerous areas to obtain information

Talents & Skills That Will Help the Character Achieve This Goal:

A Knack for Languages

Good Listening Skills

Blending In

Gaining the Trust of Others

ESP (Clairvoyance)

Empathy

Enhanced Hearing

Charm

Lip-Reading

Making People Laugh

A Knack for Making Money

Multitasking

Photographic Memory

Reading People

Self-Defense

Strategic Thinking

Possible Fallout For the Protagonist if This Goal Is Not Met:

Feeling incomplete because one doesn’t know one’s roots

Low self worth and doubt at not knowing why one was given up

Guilt that one should have tried harder or did more (in the case where the adoption was not the biological parent’s choice)

Having a lot of debt and nothing to show for it

Not knowing one’s medical history and running into possible complications as a result

Clichés to Avoid:

A “pauper to prince” scenario, where one discovers one is actually royalty and was adopted out for safety reasons (heir to a fortune, one’s enemies seeking out one’s children and killing them, etc.)

Click here for a list of our current entries for this thesaurus, along with a master post containing information on the individual fields.

Save

January 3, 2017

Tips for Weaving Romance into Your Novel

[image error]Romance is a part of life, and so it should also play some part in our novels—if we intend for our characters to mirror real life. Even if you don’t write in the romance genre, don’t be too quick to dismiss adding the element of romance to your story.

However, just slapping a few romantic moments into a scene or developing a romantic interest to add flavor may not help your story. In fact, it could even sabotage it.

Depending on your genre and plot, your story structure is going to vary. As will the role romance plays in your novel. And this is important to understand.

Romance Threads Need to Serve a Clear Purpose

Most novels have one engine that drives the story. There is one primary focus or plot the protagonist is involved with. The hero is chasing a visible goal, which is reached or not at the climax of the book. That main goal is not centered on a romantic relationship developing.

Romance, then, is a component of such a story.

If you are writing in any genre other than romance, it’s important to understand the purpose romance can serve in a story.

In most strong story structures, a romance character is either by the hero’s side from the start, acting as an ally or mirror character (who may turn rival), or she’s the “reward” at the end for the hero coming into his true essence and reaching his goal (and, of course, you can reverse the genders here).

Beware of Misdirection

When romance threads don’t follow either of these structures, they usually don’t work well.

Inserting a random romance element partway through a novel to add conflict can cause confusion because it might send the wrong message—that your story is veering in a new direction.

[image error]For example, let’s say you are writing a story about a mission to Mars. The clear plot goal for the hero (and his cast of characters) is to find a way to establish a base and start growing for because earth is dying. This is the basic premise behind the movie Red Planet.

Your hero may have a clear attraction to the female captain, and while that’s palpable to readers, that attraction merely forms the basis for allied support in the story. As the characters meet with obstacles and disasters, and tension ramps toward the climax, there might be moments when the two characters get closer, maybe even seem to be falling in love, with a hint (or more than a hint) at the end that they may get together.

But if partway through the story, the focus shifts to their relationship and the perils and joys of their blooming love, the primary plot will suffer. This applies to romantic entanglements with your secondary characters as well.

Your Chosen Genre Is a Promise to Your Reader

You make a promise to your reader when you establish your story line and genre. If your back-cover copy describes your story as a sci-fi thriller about a mission to Mars, you aren’t targeting romance readers. Those readers aren’t expecting a romance focus. They will be annoyed to see their exciting thriller turn into a romance novel.

So a romance character in non-romance genres can play a strong part, along with other ally or antagonist characters. She might betray the hero and cause him grief. Or she might provide that strong faith in him that keeps him going when all seems lost.

So, just as with the others in your cast of characters, a romance character will either help or hinder the hero in his effort to reach the goal.

We See This in Stories All the Time

We’ve all seen plenty of movies that start off showing the hero going through a divorce or having “failed” in his love relationship. In Outbreak, we see virologist Sam Daniels estranged from his ex-wife Roberta. The crisis of the outbreak throws them together, and as they face the difficult challenges together, their relationship is healed by the end of the movie. He “saves the day and wins the girl.”

This story structure is very common—and that’s because it works. No doubt you can think of a number of movies that follow this basic structure. Another that comes to mind is National Treasure—Book of Secrets, in which Ben Gates’s divorced parents, still fuming and hostile toward each other over a trivial past incident, make up at the end.

[image error]This plot element featuring secondary characters adds humor and tension and problems to the story. But it doesn’t distract or veer the story onto the wrong track. All the bits involving the romance serve the purpose of impacting and affecting Ben’s attempt to reach his goal.

Note, of course, that there is a gradual progression through the entire story, as each incident makes the two characters work through their issues until they get to a place of harmony. This would be considered a subplot for your story.

If you’d like to see how this might lay out in very specific terms, I’ve created a helpful chart that you can download here. It shows how you can layer in just about any subplot over the ten key foundational scenes for a novel.

If you keep this in mind—that any element in a novel, including a romance one—must “orbit” around the premise and plot, helping or hindering the hero in his attempt to reach his goal, you won’t go wrong.

Adding in romance elements can greatly enhance a novel—if done correctly.

In my next post for Writers Helping Writers, I’ll explore what defines a romance novel and how that structure works—and how you can layer romance scenes in over those ten primary ones.

What romance component do you have in your novel—or are thinking of adding? Can you think of any novels or movies that use this typical structure of having the hero “win the girl” in the end as a reward for reaching his goal?

[image error]C. S. Lakin is an award-winning novelist, writing instructor, and professional copyeditor who lives in the San Francisco Bay Area. Her award-winning blog for writers, Live Write Thrive, provides deep writing instruction and posts on industry trends. In addition to sixteen novels, Lakin also publishes writing craft books in the series The Writer’s Toolbox, and you can get a copy of Writing the

Heart of Your Story and other free ebooks when you join her Novel Writing Fast Track email group. Find out more about Lakin here and connect with her on social media.

Facebook | Twitter | Instagram | Pinterest

Save

Save

Save

December 31, 2016

Happy New Year! Start 2017 Right By Jumping On 3 Important Tasks

A new year is turning, and we couldn’t be more excited to see what 2017 holds for each and every one of you. A big part of making 2017 our year is getting into the right mindset to create, and to do that, we should all turn our minds to a few housekeeping items. (This is a reposting from last year that is an excellent reminder of how to start the year right.)

Housekeeping Task #1:

Back up your work.

[image error]I know, it’s obvious. And yet…do you? I mean we all know the danger of not backing up work, but let’s face it, computer crashes happen to OTHER people, right? Um, no. It can and probably WILL happen to you at some point. So, yep, back your work up. Now’s the perfect time to do it.

Housekeeping Task #2:

Do some weeding.

Weeding? Um, Angela…it’s winter. The only weeds outside are curled up in their death throes under the snow.

[image error]Bear with me…I promise it isn’t the eggnog talking. The overgrown gardens we need to turn our attention to are the word files on our computers.

Think about it…just how many versions of the same story do you have on your computer? How many blog posts, revisions of query letters, pitches, story notes, character profiles and worksheets…well, you get the idea.

Over the years, this stuff piles up. It becomes a mountain of data. The truth is, we can’t bear to let any of it go, these words of ours. We’re so sure that at some point, we’ll want that 7th revision of chapter 9, absolutely. And even if we finish the novel and move on to another, dang it, maybe that discarded paragraph 3 in that first draft can be used in a new story!

Group therapy time: we need to let some of these old files go. Once we’ve finished revisions on a book, there’s really no reason to keep all the old bits and bobs. So take a look at the scary patch of files and ask yourself, do I really need this? If you truly don’t, give yourself a Christmas gift and purge.

Housekeeping Task #3:

Okay, up until now, we’ve taken some baby steps. You’ve done well. In fact, you’re a freaking rock star. But now…we need to talk about the biggie. I know, you don’t want me to go there, but I have to. It’s the Thing That Must Not Be Named.

Your desk. Your workpace.

[image error]Yes, I know your dirty little secret…those drawers are an episode of Hoarders. Maybe several episodes. You think my desk looks any different? It doesn’t.

Here’s the deal: if we really want to give ourselves a clear mind in January, we need to clean our surroundings. Make our fresh start a TRUE fresh start.

If your desk is a mess, your drawers are filled with God-knows-what, and there’s so much of it you haven’t seen the bottom in a good year or two, it’s time to excavate.

Trust me, you will feel so much better knowing those drawers actually shut like they are supposed to. And it probably won’t kill you to dust. Or empty the trash. So sort, organize and recycle!

[image error] And here’s a bonus tip for making this your year…check into One Stop For Writers.

Story structure tools, generators unlike anything you’ve seen, a massive description database on emotion, setting, character traits, symbolism, weather and more (13 topics in all), plus a ton of worksheets, templates, tutorials and writing lessons… One Stop For Writers can really give your writing career a boost.

Registration is free, so why not stop by?

Here’s to a fantastic 2017. We hope it is your best year yet!

Happy writing & organizing!

~Angela & Becca

Image 1: HerbieFot @ Pixabay

Image 2: Elizabethmh @ Pixabay

Image 3: Nathan Copely @ Pixabay

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

November 8, 2016

Mastering Stylistic Tension

One of the first things writers learn is to start a story with conflict. Some writers have bombs go off. Others start with a death. Or a break-up. But over the years, looking at unpublished material, I’ve learned and relearned that how such conflicts are rendered on the page stylistically can often be just as important as the conflict itself, and sometimes even more important.

One of the first things writers learn is to start a story with conflict. Some writers have bombs go off. Others start with a death. Or a break-up. But over the years, looking at unpublished material, I’ve learned and relearned that how such conflicts are rendered on the page stylistically can often be just as important as the conflict itself, and sometimes even more important.

I’ve seen a lot of stories start with the dead or dying—a topic that is universal to the human experience. And yet, stories that promise a content-minor conflict on something like, say, a character losing her job, seem to have more tension. Why is that?

Often it’s based on how the writer handles the conflict stylistically. In some ways, it’s not the conflict itself that draws readers in, it’s the promise of conflicts. A story that opens blatantly with death often isn’t as interesting as a story that opens with the promise of death—whether that death happens on the first page or last page of the story.

When you begin a story with a death itself . . . that’s it. It’s all there, on the page. But when you begin a story with a promise of death, the reader feels the need to read on to find out about the death and discover whether or not is actually happens.

Weeks ago, when doing some research, I ran into this article on Writer’s Digest, which makes a few articulate statements on what I’m talking about today. It points out that showing the audience the cat in the bag isn’t near as interesting as mentioning only a whisker or paw poking out of the bag. The article goes on to give these two examples that I’m going to borrow:

The blackened mask had two slits for the eyes and a triangular hole where the nose would fit. Lips pierced by claw-like teeth were painted where the mouth would have been, and my mind screamed the question … would I be victim or victimizer this time?

This example shows us the entire “cat.” The content has tension, but the way it’s rendered it so straightforward, it nearly robs the passage of tension.

Compare that example to this one:

“I didn’t know you’d gone to acting school,” she said.

He laughed. “My father’s idea. I only lasted two months, and I was pretty bored.” He pushed himself from the chair. “What about that pizza?”

The content of this example is pretty simple, and yet, the way it’s presented carries a sense of uncertainty about it. The female implies that she should have already known about acting school, which subconsciously makes us wonder why she doesn’t, and if the male is hiding something.

When the male laughs it off, downplays it, and changes the subject, we are left to feel more uncertain. We are left feeling tension, even if we can’t consciously point to it on the page.

In short, the second example lets us glimpse a whisker or paw, and not the whole cat.

In short, the second example lets us glimpse a whisker or paw, and not the whole cat.

Please note that there are times we should probably see the whole cat, like at the climax of the story. But even then, your story might have more power by leaving an ear or tail in shadow. This all goes back, again, to the power of implying things in writing, instead of saying everything straight out. When we imply things, the reader becomes more of a participator in the story, which leads to them being invested in the story.

Questions (often subconscious ones) are what hook a reader, not answers to things they don’t yet care about.

Can you start a story with a blatant death? Of course, but in the process, you want to promise other conflicts. The death should push the door wide open to big problems. It should be the vehicle that lets you promise more tension. It creates more problems rather than being the sum of the problems. Same with openings where bombs go off and break-ups happen, etc.

Ultimately it’s this stylistic skill of only showing a whisker that makes “simple” stories feel significant. It’s one reason why a story opening about a conflict between a father and daughter can sometimes feel more interesting than a story opening with the president being assassinated. If the opening is only about the president being assassinated, it won’t have the promises that make readers want to keep reading. Whereas, a minor argument between a parent and child that has promises of future tension might make us want to read more.

So, in opening your story (and even throughout), remember that it’s not the conflict alone that draws readers in, it’s the promise of tension in the future. Don’t put the whole cat on paper.

What ways do you promise your readers conflict? Let us know in the comments!

Sometimes September scares people with her enthusiasm for writing and reading. She works as an assistant to a New York Times bestselling author while penning her own stories, holds an English degree, and had the pleasure of writing her thesis on Harry Potter. Find out more about September here, hang with her on social media, or visit her website to follow her writing journey and get more writing tips.

Sometimes September scares people with her enthusiasm for writing and reading. She works as an assistant to a New York Times bestselling author while penning her own stories, holds an English degree, and had the pleasure of writing her thesis on Harry Potter. Find out more about September here, hang with her on social media, or visit her website to follow her writing journey and get more writing tips.

Facebook | Twitter | Tumblr | Instagram | Google+

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

The post Mastering Stylistic Tension appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS®.

November 5, 2016

Character Motivation Entry: To Right A Deep Wrong

What does your character want? This is an important question to answer because it determines what your protagonist hopes to achieve by the story’s end. If the goal, or outer motivation, is written well, readers will identify fairly quickly what the overall story goal’s going to be and they’ll know what to root for. But how do you know what outer motivation to choose?

If you read enough books, you’ll see the same goals being used for different characters in new scenarios. Through this thesaurus, we’d like to explore these common outer motivations so you can see your options and what those goals might look like on a deeper level.

If you read enough books, you’ll see the same goals being used for different characters in new scenarios. Through this thesaurus, we’d like to explore these common outer motivations so you can see your options and what those goals might look like on a deeper level.

Character’s Goal (Outer Motivation): To Right a Deep Wrong

Forms This Might Take: there are many types of injustices that may resonate with your character, based on their personality, ties to the past, their experience with marginalized groups or people, exposure to different parts of the world and the challenges there, or to causes and beliefs they hold dear. Possible examples might include

advocacy for animals or natural resources

advocacy for a group of people who have suffered mistreatment

working to bring about change in an area that has been overlooked (the living conditions of children living in third-world orphanages, animal cruelty, poverty, etc.)

championing a cause (mental health awareness, tackling homelessness, human rights, etc.)

building a charity or foundation to help others

investigating a situation and then publicizing one’s findings to make an injustice known

seeking justice on behalf of an individual or family (to restore a reputation, have credit for something attributed to them, to honor them for a sacrifice or heroic deed)

help make amends for something one feels in part responsible for (one’s white privilege, trying to rectify something one’s ancestors did, etc.)

to atone for something one did in the past that was irresponsible or caused hurt in some way

Human Need Driving the Goal (Inner Motivation): Self-Actualization

How the Character May Prepare for This Goal:

soul searching to try and figure out how one might help the situation

traveling to study the problem and collect data, or witness the results of unchecked abuse first hand (visiting the site of polluted waters, a child labor camp, a factory farming location, etc.)

take action to protect a person, place or thing that is in immediate danger

interviewing people who are at the center of the marginalization or injustice

digging up old evidence and researching to bring new facts to light

fundraising to help the victims

volunteering to be accountable for the effort to put a stop to what’s happening

planning an event to draw visibility and support for one’s cause

starting a website dedicated to the cause one is championing

planning meetings and working to draw others in to help

reaching out to organizations who may be able to assist (Amnesty International, etc.)

staging protests or peaceful rallies to gain visibility for the situation or cause

petitioning police or lawmakers to re-open a case, change a law, recognize a situation and investigate, or step in in some way

arranging meetings with influential people who may be able to help

approaching the media to raise awareness

taking one’s fight or cause to social media for visibility

public speaking events (in schools, universities, or at conferences) to raise awareness and educate

investing one’s time and money to help balance the scale by working to improve the lives of others, support victims, and be on scene in any way that is needed, enduring hardship if necessary

take personal responsibility for one’s role by going to the police, media, or the victims, etc. to apologize and accept consequences

Possible Sacrifices or Costs Associated With This Goal:

damaged relationships with family and friends who don’t understand or agree with one’s mission

financial hardship as one uses one’s own money to fight for others, pay for necessary studies, tests, infrastructure, travel, etc.

a job loss if one’s mission begins to impact one’s day job

health deterioration due to stress or testing one’s physical limits

a loss of esteem in the eyes of others who don’t agree with one’s choices

irreversible family fallout (a divorce, children who refuse to have a relationship with the character) because one’s mission or cause always came first

having one’s reputation damaged by those who oppose one’s cause in order to weaken one’s position

being harassed or threatened (or having one’s family harassed and threatened) by corrupt agencies or people in power who are invested in information being locked up tight

being hurt or killed when one crosses the wrong people

public shaming and possible rejection by one’s loved ones and peers if one was personally responsible for the past damage and is now owning up to it to rectify the situation

charges laid or incarceration if one is personally responsible for a crime

hardship due to legal fees

Roadblocks Which Could Prevent This Goal from Being Achieved:

corrupt governments and officials

powerful corporations with deep pockets who an invested interest in having one’s cause go away, or silencing one’s voice

legal red tape

witnesses or victims who are being intimidated into staying silent

evidence “going missing”

having one’s access to a person, group, place, set of documents, etc. being removed by someone with the power to do so

a lack of interest from the public regarding one’s cause

people who have conflicting interests making trouble

having a personal skeleton come out of the closet which weakens one’s platform and reputation

discovering a source of information one has relied on is false

finding out that a trusted member of one’s group has mismanaged funds or broken the law in some way, discrediting one’s charity, foundation, or cause

a health crisis

a personal tragedy

being framed for something in order to divert attention or discredit

Talents & Skills That Will Help the Character Achieve This Goal:

Being a Good Listener

Blending In

Empathy

Exceptional Memory

Having a Silver Tongue

Midas Touch

Multitasking

Promotion

Strategic Thinking

Reading people

Possible Fallout For the Protagonist if This Goal Is Not Met:

disillusionment at society as a whole

disappointment in oneself

self-loathing (if one was personally responsible and unable to fix the damage)

guilt at not doing more

second guessing oneself and the work one did

being unable to enjoy life the way one once did

resentment toward others who did not help (or help as much as they could have) leading to damaged relationships

having to “start over” because one’s finances have been drained

Clichés to Avoid:

the struggle to win against an adversary (a corporation, a government agency, society’s beliefs, etc.) being straightforward. The reality is any situation of injustice will have many different facets, and will affect many different individuals and levels of power–if it didn’t, the past wrong would have been fixed before now. Many moving pieces need to be factored in to formulate a realistic battle plan, and many different types of obstacles will need to be overcome by the protagonist (financial, environmental, dealing with interest groups with opposing views, dealing with public misinformation and ignorance, etc.)

Click here for a list of our current entries for this thesaurus, along with a master post containing information on the individual fields.

Image: vleyva @ pixabay

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

The post Character Motivation Entry: To Right A Deep Wrong appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS®.

November 1, 2016

Understanding Inner Conflict with Story Expert Michael Hauge

All stories are built on a foundation of three basic components: character, desire, and conflict. A hero or protagonist desperately wants something, and must overcome seemingly insurmountable obstacles to achieve it.

All stories are built on a foundation of three basic components: character, desire, and conflict. A hero or protagonist desperately wants something, and must overcome seemingly insurmountable obstacles to achieve it.

The greater that conflict is, the greater the emotional involvement of readers and audiences.

Almost all successful stories involve external conflict for their heroes – obstacles created by other characters or forces of nature. But in stories that explore the deeper levels of character, the greatest obstacle the hero faces comes from within. This is the character’s inner conflict.

The heroes of these stories always carry some wound from the past – a deeply painful event or situation that the character believes she has resolved or overcome, but which is still affecting her behavior.

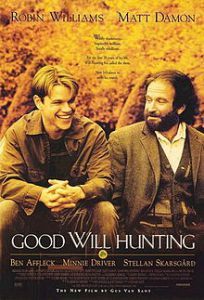

In Good Will Hunting, Will’s wound is the abuse he suffered when his father beat him. For the heroes of Gravity and Collateral Beauty the wound is the death of a child. In Up and Sleepless In Seattle it’s the death of a spouse. And for Judy Hopps in Zootopia, it’s the beating she got from a predator bully when she was a young rabbit.

In Good Will Hunting, Will’s wound is the abuse he suffered when his father beat him. For the heroes of Gravity and Collateral Beauty the wound is the death of a child. In Up and Sleepless In Seattle it’s the death of a spouse. And for Judy Hopps in Zootopia, it’s the beating she got from a predator bully when she was a young rabbit.

When characters are traumatized by these experiences, they formulate beliefs about the world that will protect them from ever again experiencing the pain of those wounds.

Will Hunting believes he must have deserved those beatings, so he can never let anyone see who he really is. Sam in Sleepless In Seattle believes real love “doesn’t happen twice.” Carl in Up, Ryan in Gravity and Howard in Collateral Beauty believe that if they let go of the pain of their grief and move forward with their lives, they will lose even the memories of their loved ones – a level of pain they would never survive. And deep down, Judy Hopps believes predators really are inherently bad – regardless of what she preaches to the outside world.

Notice that these beliefs that grow out of past wounds are never true. But they are ALWAYS logical.

So each of these characters’ subconscious mind creates what I term an identity – a persona or mask that the character presents to the world to feel safe.

Will Hunting hides his genius by working as a janitor at MIT; Carl becomes a reclusive grouch; Sam refuses to “grow a new heart;” Ryan floats in space, as far from earth – and reality — as she can get; Howard, mired in his pain, ignores his responsibilities and stops talking altogether; and Judy Hopps hides her own prejudice by being a seemingly open minded cop.

But then something happens that forces each of these heroes to confront his or her fears: they all desperately want something.

This is how you as a writer and storyteller instill the inner conflicts in your characters that will ultimately empower them to transform: you give them compelling desires that will force them to let go of their protective identities. Then, as they pursue those goals, they will come to realize the truth of who they are underneath their masks.

This truth is what I term a character’s ESSENCE.

So Will Hunting falls in love, and Ryan must get back to Earth, and Carl wants to get his house to Paradise Falls, and Judy must stop the villain who is making animals disappear.

But now these heroes have a real dilemma: give up on the things they desperately want; or drop the identities that keep them feeling safe.

So for the entire story, your hero will be in an emotional tug-of-war: remain safe but unfulfilled in her identity; or go after her goal and be scared to death.

This tug-of-war between living in fear and living courageously is your hero’s INNER CONFLICT.

And the gradual transformation from fear to courage – from identity to essence – is the character’s ARC.

In most stories this inner conflict is more difficult to overcome than the external conflict. Because it means confronting a fear so deeply ingrained, and a wound so painful, that it can seem impossible.

Just as in real life, given a choice between safe and happy, we will almost always choose SAFE.

And so it is with your characters.

This is why it takes the entire story for Will Hunting to declare his love for Skylar and let her see who he truly is; and for Ryan to literally take those first steps toward living again; and for Carl to let go of the house – and the past – he’s been dragging behind him and instead help Russell and Doug save Kevin; and for Sam to take Annie’s hand on the Empire State Building.

As you develop your next novel or screenplay, give your hero a wound – a painful event or situation from the past – that that has made him who he is at the beginning of the story. Then make sure that whatever motivation your hero is desperate to achieve, pursuing it will force him to gradually shed his protective identity in order to achieve it.

As you develop your next novel or screenplay, give your hero a wound – a painful event or situation from the past – that that has made him who he is at the beginning of the story. Then make sure that whatever motivation your hero is desperate to achieve, pursuing it will force him to gradually shed his protective identity in order to achieve it.

Then once you have defined your hero’s identity and essence – once you know the inner conflict – make certain it informs every scene in your story. Make sure that every action your hero takes is either a retreat back into his identity, moving him further away from success, or a step closer to his essence – and to achieving his goal, living his truth, and finding transformation and fulfillment.

– Michael Hauge

Psst, Angela here. I’m going to add a great video interview with Michael Hauge on What Screenwriters Should Know About The Character’s Inner Journey. Have a watch.

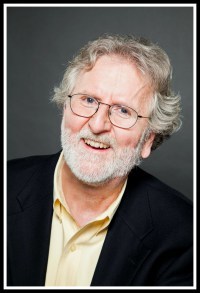

Michael has been one of Hollywood’s top script consultants, story experts, and speakers for more than 30 years, and is the author of Selling Your Story in 60 Seconds and Writing Screenplays That Sell.

Michael has been one of Hollywood’s top script consultants, story experts, and speakers for more than 30 years, and is the author of Selling Your Story in 60 Seconds and Writing Screenplays That Sell.

Find out more about Michael here, check into his articles and coaching packages at Story Mastery, and catch up with him on social media.

Do you struggle with Inner Conflict? What is your protagonist struggling with? Let us know in the comments!

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

The post Understanding Inner Conflict with Story Expert Michael Hauge appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS®.

October 29, 2016

Character Motivation Thesaurus Entry: Mending a Broken Relationship

What does your character want? This is an important question to answer because it determines what your protagonist hopes to achieve by the story’s end. If the goal, or outer motivation, is written well, readers will identify fairly quickly what the overall story goal’s going to be and they’ll know what to root for. But how do you know what outer motivation to choose?

If you read enough books, you’ll see the same goals being used for different characters in new scenarios. Through this thesaurus, we’d like to explore these common outer motivations so you can see your options and what those goals might look like on a deeper level.

Courtesy: Pixabay

Character’s Goal (Outer Motivation): Mending a Broken Relationship

Forms This Might Take: Relationships founder for many reasons, leaving our characters in a position of trying to put them back together. Your character might find herself needing to mend a less-than-satisfactory relationship with

an estranged sibling

a caregiver whose parenting left something to be desired, leading to distance in the relationship

children she doesn’t know as well as she wants to (due to a long-term absence, divorce, a drug problem that has been overcome, etc.)

a childhood friend she grew apart from after an argument

an ex she never quite got over

a spouse who’s emotionally distant and considering a separation

a jealous co-worker she now has to work with

a difficult neighbor

the person her son or daughter is going to marry

Human Need Driving the Goal (Inner Motivation): love and belonging

How the Character May Prepare for This Goal:

Setting up a meeting with the person

Calling him or her on the phone

Moving nearer to that person

Showing the person one’s determination by giving up something important that once stood in the way of the relationship (a job, a hobby, another unhealthy relationship, etc.)

Reaching out to him or her on social media

Doing recon to find out more about the person’s interests and passions

Bringing the person a peace offering (favorite flowers, chocolates, a coffee on a cold day, etc.)

Arranging to meet the person in a group setting before getting together one-on-one

Showing interest in the person’s favorite sports team, TV show, music groups, etc.

Building bridges with the person’s close friends or relatives as a way of getting closer to him or her

Cutting back one’s work hours or taking a sabbatical so one can devote more time to the relationship

Creating time in one’s schedule to spend with that person

Going to counseling

Recognizing the part one played that contributed to the problem, and owning it

Asking forgiveness

Employing a neutral mediator to help bridge the gap

Possible Sacrifices or Costs Associated With This Goal:

Pride taking a hit when one truly looks at the part one played in the broken relationship

Moving closer to the estranged person and leaving one’s job or friends behind

Other relationships becoming strained if the people don’t understand why one is reaching out to this person (if the estranged relationship is due to past abuse, for instance)

Asking for forgiveness that isn’t granted

Being rejected

Giving up something one loves (a job, hobby, or relationship) to show the other person how important the relationship is

Time

Having to face the prejudice and bad feelings of those close to the estranged person who want to protect him or her

Roadblocks Which Could Prevent This Goal from Being Achieved:

People in the person’s life who don’t want to see him or her hurt again

People in one’s life who don’t want to see one hurt again

Selfishness

Falling into old habits that sabotage the new relationship

The other person’s fear, resentment, or anger

Old wounds that are too deep to overcome

Geographical distance

Time limitations

Jealous or petty family members who don’t want the relationship fixed

Habits that contributed to the break-up that one of the parties still struggles with (addictions, character flaws, etc.)

Personality conflicts

An unethical counselor with an unhealthy interesting in one of the parties

Talents & Skills That Will Help the Character Achieve This Goal:

Being a good listener

Empathy

Reading people

The ability to win people over

Manipulation

Possible Fallout For the Protagonist if This Goal Is Not Met:

Unfulfilled relationships

Doubting one’s abilities to be a good parent/spouse/sibling/etc.

Giving up and regressing into destructive habits

More broken relationships as one reverts back to patterns one is comfortable with

Loneliness

Clichés to Avoid:

The big city girl/boy returning to his/her small home town to make amends with someone

Click here for a list of our current entries for this thesaurus, along with a master post containing information on the individual fields.

The post Character Motivation Thesaurus Entry: Mending a Broken Relationship appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS®.

October 27, 2016

5 NaNoWriMo Hacks To Keep Words Flowing

It’s hard to believe but NaNoWriMo is almost here. Becca and I won’t be participating officially, but our November definitely includes putting miles on our Emotional Wound Thesaurus book.

It’s hard to believe but NaNoWriMo is almost here. Becca and I won’t be participating officially, but our November definitely includes putting miles on our Emotional Wound Thesaurus book.

I thought I’d pass on a few hacks I’ve learned that have helped me out many a time during NaNo.

1. Start with a plan (yes, even the Pantsers). Really, the more you know about your plot and characters going in, the more it helps. Understanding what motivates your hero and why is the golden thread of your story, so don’t go in blind. There will be plenty of room for pantsing, trust me.

2. If you get stuck on what comes next, skip ahead. Think about the story ahead and the next scene you see clearly in your mind. Maybe it’s two scenes down the road, or two chapters. Either way, put a placeholder into your book like, “Cindy is released from prison on a technicality” and then jump forward to the next scene you know will happen, like Cindy stalking the only witness to the crime. Words flow again, and in the background, you brain can work on the problem. When the answer hits (and it will), you can “fill in” the missing scene.

3. Hate the scene? Change the setting and rewrite it. Many don’t realize it, but setting choice is a pretty big deal. How well the scene works is influenced by how well you utilize your setting, so choosing the right one is important. You can really mess with a character’s emotions, alter the mood, create conflict, and home in on fears, hopes or dreams as you need to, all using the setting. Here’s 4 ways to nail down the best setting choice for each scene. (Psst, if you rewrite the scene, keep the old one as it’s part of your 50K word count!)

4. Always end the session knowing the next line. We can lose momentum between writing sprints–one minute the words are flying, the next, nope. If you are writing a scene and need to quit for the day, try not finishing it…wait and pick it up again in your next session. Or, start the next scene just enough that you see the direction and then stop. This will help you get into the flow faster and keep the paralyzing fear of WHAT COMES NEXT at bay.

4. Always end the session knowing the next line. We can lose momentum between writing sprints–one minute the words are flying, the next, nope. If you are writing a scene and need to quit for the day, try not finishing it…wait and pick it up again in your next session. Or, start the next scene just enough that you see the direction and then stop. This will help you get into the flow faster and keep the paralyzing fear of WHAT COMES NEXT at bay.

5. Triage, Triage, Triage. Getting stuck or stumped may happen. Let’s be real–it probably will happen. But that’s totally okay because all you need to do is visit the NaNoWriMo Triage Center. You can find help for Character Issues, Plot Problems, Conflict Juicing, Story Middle Problems, plus a bunch of brainstorming links.

Joining the NaNoWriMo frenzy? What are your favorite tips? Share them in the comments!

Oh, and before I forget, if you have heard about our other site One Stop For Writers, now’s a great time to check it out. In fact, if you use this coupon before the end of November 2016:

Oh, and before I forget, if you have heard about our other site One Stop For Writers, now’s a great time to check it out. In fact, if you use this coupon before the end of November 2016:

NANOWRIMO_FTW16

…your first month is only $4.50.

November seems like a good time to have instant access to 12 description thesauruses (emotions, setting, weather, symbolism, skills & talents, physical features, colors, positive attributes, character flaws, emotion amplifiers, and others), doesn’t it? And of course there’s also a ton of writing tutorials, lessons, story maps, timeline tools, generators, and other writerly stuff there too.

So, consider skipping a latte this month and invest in One Stop For Writers instead. All the details are in this month’s newsletter (which is also stuffed with great NaNoWriMo resources, too.)

Becca and I are cheering you all on!

Writers Helping Writers

- Angela Ackerman's profile

- 1014 followers