Angela Ackerman's Blog: Writers Helping Writers, page 123

June 13, 2017

A Question of When: Indicating Time Passage in Our Stories

[image error]Today, we’re going to discuss a question a WHW reader previously submitted to the Resident Writing Coaches. Nancy C. asked:

“I would like to know more about how to show the passing of time between scenes (other than dates or ‘one week later’ at the beginning of the chapter).”

Great question, Nancy! *smile* Before we get to the answer, let’s first recap why it’s important for our readers to be at least vaguely aware of the time frame of our scenes:

Time—just like location—establishes our story’s setting, which anchors readers in our story.

Without an anchored setting, readers might be distracted from digging into our story, as they struggle to correctly interpret events in their head. And time—especially the passage of it—can be just as important as our beautifully described locations in giving readers that anchor.

Including the passage of time can also make our story more believable. Readers are more likely to give us the benefit of the doubt if they’re not expected to swallow that our characters instantly fall in love, learn new skills, overcome their emotional issues, research how to beat the bad guys, etc.

So how can we indicate the passage of time in our story? Here are a few options beyond listing a date line above our scene or starting with “One week later…”

Option #1: Use Weather of the Seasons

If the previous scene took place during a summer heat wave, readers will understand that time has passed if the next scene mentions the russet colors of falling leaves or a wind-whipped snowstorm.

Freezing sleet drenched her thin jacket and made her long for the warm breezes of last summer.

Option #2: Setup a Wait and Payoff an Event

If the previous scene mentioned that the characters were waiting for something (receiving a message, another character catching up with them, an upcoming holiday, etc.), the next scene can jump to that event.

The medicine arrived in the mail on the promised day, and she grasped the tiny bottle with shaking hands. One more day, and it might have been too late to reverse the infection.

Option #3: Contrast What the Time Passage Could Have Been

[image error]

Related to Option #2, if our characters and readers are expecting a wait, we can indicate how much time has passed by contrasting the actual amount with the expected amount.

Even though the instructions had said to wait two weeks, impatience got the better of her after ten days, and she dialed the number listed for Receiving Your Laboratory Test Results.

Option #4: Highlight What’s Changed—or Hasn’t Changed

Similar to Option #2 but without an expected wait, a scene can show whether anything has changed from the previous situation.

With every month that passed after the loss of her mother, her friends assumed her grief would lessen, but no amount of time would relieve the ache in her heart.

Option #5: Bring a Character Up to Speed

If a character misses events, another character could catch them up on what they missed.

“Thank goodness you’re finally here. Your father has been asking for you for weeks.”

Option #6: Use a Literary “Montage”

We’re probably all familiar with the “training montage” scene in movies, and even though that’s a visual technique, we can do something similar in our writing by contrasting a before and after.

From one day to the next, her accuracy improved until—after more weeks than she wanted to admit—she could finally hit the bullseye with every shot.

Option #7: “Hand Wave” Away the Time Passage

The opposite of Option #6, we can tell readers that time passed quickly while not much was happening.

At her stomach’s grumble, she glanced at the clock to see which meal she’d forgotten this time. Mealtimes—and days and nights—had passed in a hazy blur lately as she pretended the last message from Headquarters hadn’t changed her life forever.

Caution: Don’t Lose Readers by Skipping Information

While most of the examples above don’t use specific phrases like “three weeks later,” they still vaguely indicate how much time has passed—at least as far as days, weeks, months, or years. A passage of days is very different from that of months, and readers usually need the unit of time for an anchor.

Also, we don’t want readers to feel left out from whatever happened in the interim. As shown in the examples, we can keep readers connected to our story by hinting at how our characters spent the time: activities (training, traveling, researching), their emotional state (grief, impatience, survival mode), etc.

Do you have questions about any of these options, or can you think of other ways to indicate time passage in our stories?

[image error]After muttering writing advice in tongues, Jami decided to put her talent for making up stuff to good use. Fueled by chocolate, she creates writing resources and writes award-winning paranormal romance stories where normal need not apply. Just ask her family—and zombie cat.

Find out more about Jami here, hang out with her on social media, or visit her website and Goodreads profile.

Facebook | Twitter | Pinterest

Save

Save

Save

Save

June 10, 2017

Character Motivation Entry: Trying Again When One Has Previously Failed

What does your character want? This is an important question to answer because it determines what your protagonist hopes to achieve by the story’s end. If the goal, or outer motivation, is written well, readers will identify fairly quickly what the overall story goal’s going to be and they’ll know what to root for. But how do you know what outer motivation to choose?

[image error]If you read enough books, you’ll see the same goals being used for different characters in new scenarios. Through this thesaurus, we’d like to explore these common outer motivations so you can see your options and what those goals might look like on a deeper level.

Character’s Goal (Outer Motivation): Trying Again When One Has Previously Failed

Forms This Might Take:

An athlete who was injured before reaching a specific level of achievement

Returning to school after dropping out

Summiting a mountain after having to turn back before

Achieving the title belt after losing previously

Sailing completely around the world

Completing a religious pilgrimage

Completing a specific journey or trek one attempted before

Raising the money needed to start a new business

Successfully bringing family into the country to live

Publishing a book or memoir

Inventing a specialized computer program or application

Discovering a cure for a disease

Making an important scientific discovery

Reconnecting with family after a fallout or breach

Successfully living life off the grid

Finding a lost relative or birth family

Mastering a particular skill or solving a difficult and vexing problem

Human Need Driving the Goal (Inner Motivation): self-actualization

How the Character May Prepare for This Goal:

Alter one’s eating habits to improve nutritional health

Strength-training and physical conditioning

Researching an area of expertise

Reconditioning one’s skills

Purchasing equipment, gear, or other supplies

Collecting data around a particular subject

Studying others who have succeeded (videos, interviews, reading memoirs or papers)

Finding a mentor

Asking others for help

Fundraising

Undergoing rigorous training

Meditation

Working out unresolved issues with a therapist

Practicing by achieving smaller goals

Possible Sacrifices or Costs Associated With This Goal:

Spending one’s savings to work toward achievement

Giving up employment to go on a sabbatical or travel

Placing more financial and emotional strain on other family members in one’s absence

Relationship difficulties due to time constraints or a lack of support for one’s path

Stirring up old memories and fears of failure

Pushing one’s body to unsafe limits

Roadblocks Which Could Prevent This Goal from Being Achieved:

Age taking its toll and one’s body becoming compromised (if the goal is physical)

Mental fatigue

Bad weather or unsafe conditions (if travel is an element)

Competition that is just as determined to reach the goal themselves

A crisis of faith

Running out of funds

Permissions needed being revoked

Political red tape

Ethical or moral roadblocks

An illness or injury that compromises one’s health or abilities

Talents & Skills That Will Help the Character Achieve This Goal:

Note: the below are generalized skills that may help, but depending on the nature of the individual goal, many different specific skills and talents may aid the character in achievement.

Possible Fallout For the Protagonist if This Goal Is Not Met:

Feeling incomplete

Regret, feeling one has failed, again

Feeling unfulfilled

Lower self-esteem

Clichés to Avoid:

Going up against the same rival one was bested by before

Click here for a list of our current entries for this thesaurus, along with a master post containing information on the individual fields.

Save

Save

June 8, 2017

Critiques 4 U!

Hi, everyone! Can you believe it’s June? I’m SO looking forward to turning off my alarm clock for two months and soaking up the sun. But there are still 3 weeks of school (for us) to get through in the meantime, so let’s do some critiques, shall we?

If you’re working on a first page and would like some objective feedback, please leave a comment that includes:

1) your email address. Some of you have expressed concern about making your email address public; if you’re sure that the email address associated with your WordPress account is correct, you don’t have to include it here. But if you do win and I’m unable to contact you through that email address, I’ll have to choose an alternate winner.

2) your story’s genre (no erotica, please)

Also, please be sure your first page is ready to go so I can critique it before next month’s contest rolls around. If it needs some work and you won’t be able to get it to me right away, I’d like to ask that you plan on entering the next contest, once any necessary tweaking has been taken care of.

June 6, 2017

Let Your Characters Live and Breathe

[image error]In my collection of writing books is a 1919 title, A Manual of the Art of Fiction, by one Clayton Meeker Hamilton, a professor at Columbia University. It’s a bit academic, but I’ve found some gems in it. Among them is the following. In his chapter on characterization, Hamilton states:

“The careless reader of fiction usually supposes that, since the novelist invents his characters and incidents, he can order them always to suit his own desires: but any honest artist will tell you that his characters often grow intractable and stubbornly refuse at certain points to accept the incidents which he has foreordained for them, and that at other times they take matters into their own hands and run away with the story. Stevenson has recorded this latter experience. He said, apropos of Kidnapped, “In one of my books, and in one only, the characters took the bit in their teeth; all at once, they became detached from the flat paper, they turned their backs on me and walked off bodily; and from that time my task was stenographic––it was they who spoke, it was they who wrote the remainder of the story.”

Has that ever happened to you? I suspect it has. It’s one of the most pleasurable aspects of writing (though a little daunting if you’re a dedicated outliner).

So what should you do when a character starts making a few moves of his own?

Listen

As Madeleine L’Engle once put it, “If the book tells me to do something completely unexpected, I heed it; the book is usually right.”

[image error] Take a breath and just let the turn of events soak in. When writing No Legal Grounds, about the stalking of a lawyer and his family, I had planned all along for the wife to leave the house and go off to stay with her sister. But when I got to that scene she wouldn’t go. Just wouldn’t do it. I tried to make her, but she told me to go pound sand.

Take a breath and just let the turn of events soak in. When writing No Legal Grounds, about the stalking of a lawyer and his family, I had planned all along for the wife to leave the house and go off to stay with her sister. But when I got to that scene she wouldn’t go. Just wouldn’t do it. I tried to make her, but she told me to go pound sand.

So I walked around my writing desk thinking about it. I listened to her reasons. And it turns out she was right for her. She became a stronger character. Of course, I had to change my plans from that point on, which brings me to:

Re-Imagine

Whether you are a plotter or a “pantser,” now is the time to jot some free form notes on this new development. Start with a general document on plot possibilities. Ask yourself questions like:

What further trouble can happen to this character?

What sorts of things has this character unloosed by her independent actions?

How have the other character relationships changed?

And so on. Next, add to your character’s voice journal (this is an exercise I follow and recommend in all my workshops. It’s a stream-of-consciousness document in the character’s own voice). Let the character talk to you about what’s going on, and what she might want to do about it.

Plan and Write the Next Two Scenes

Don’t worry about changing your entire outline just yet. Just do the next two scenes. Write them. The act of writing itself is the most important way to let the characters live and breathe. Get a feel for who they are now by writing out the consequences. Then you’ll be in much better shape to write to the end.

So what about you? Do your characters ever take off on you? How do you handle it? (I’m on the road so may not be able to comment much, but please go ahead with the conversation!)

Jim is the author of the #1 bestseller for writers, Plot & Structure, and numerous thrillers, including, Romeo’s Rules, Try Dying and Don’t Leave Me. His popular books on fiction craft can be found here. His thrillers have been called “heart-whamming” (Publishers Weekly) and can be browsed here. Find out more about Jim on our Resident Writing Coach page, and connect with him online.

June 3, 2017

Character Motivation Thesaurus: Escaping Homelessness

What does your character want? This is an important question to answer because it determines what your protagonist hopes to achieve by the story’s end. If the goal, or outer motivation, is written well, readers will identify fairly quickly what the overall story goal’s going to be and they’ll know what to root for. But how do you know what outer motivation to choose?

If you read enough books, you’ll see the same goals being used for different characters in new scenarios. Through this thesaurus, we’d like to explore these common outer motivations so you can see your options and what those goals might look like on a deeper level.

[image error]Character’s Goal (Outer Motivation): Fleeing One’s Homeland

Forms This Might Take:

One of the most basic human needs is shelter. When an individual or family has no home of their own, their other basic needs become endangered. For this reason, finding a home of one’s own can be a driving force for someone who is homeless.

It should be noted that there are often factors contributing to one’s homelessness that are seemingly insurmountable, making the goal extremely difficult to overcome: addiction, mental illness, physical disabilities, and the need to pay for medications one can’t afford. Some of these factors can cause the person to abandon or sabotage this goal. Please know that this entry outlines some of the ways a person could achieve this motivation while understanding the very difficult, complex circumstances surrounding it.

Human Need Driving the Goal (Inner Motivation): physiological needs

How the Character May Prepare for This Goal:

Finding temporary lodgings (at a shelter, the YMCA, a motel, with a friend, in an abandoned building, etc.)

Borrowing money from a friend to secure the things one needs in order to get a job (clothing, shoes, toiletries, etc.)

Asking for help at a local church, shelter, or nonprofit organization

Finding a way to keep up with one’s hygiene

Securing a job

Arranging for someone to care for one’s child after school, so one can work

Overcoming a drug or alcohol addiction

Researching affordable home options

Planning a budget that will allow one to save up the money needed to get an apartment

Selling any valuable items one might have (a car, jewelry, etc.) to obtain money for a security payment or first month’s rent

Stealing money or items from others

Obtaining any necessary identification (birth certificate, driver license, etc.)

Completing a skills course that will enable one to secure a job

Maintaining a positive attitude

Facing one’s past so one can move forward

Possible Sacrifices or Costs Associated With This Goal:

Facing the pain of things one might have been avoiding (failing, reconnecting with estranged family and friends, the truth about one’s addiction or mental illness, etc.)

No longer being on one’s own; having to be responsible for and to others

Having to live life according to a more traditional set of rules and expectations

Being rejected (by potential employers, landlords, etc.)

Getting one’s hopes up only to have them destroyed again

Facing prejudice, ambivalence, or scorn due to one’s homeless status

Giving up the things one has become accustomed to, even if they’re less than ideal or even harmful

Having to depend on others for help (instead of solely on oneself)

Having to lie or deceive in order to achieve the goal (by giving a fake address, making up details from the past, etc.)

Roadblocks Which Could Prevent This Goal from Being Achieved:

Self-doubt and fear

Drug and alcohol addiction

Mental and physical disabilities

Lack of an ability to maintain good physical hygiene

Being unable to afford the things one needs to achieve the goal (a downpayment on an apartment, working clothes, food, laundry services, transportation, etc.)

Negative influences who don’t want one to succeed

Shelters and food kitchens that are full to capacity or closing down due to budget cuts

An injury or illness that occurs as one is just starting to bounce back

Talents & Skills That Will Help the Character Achieve This Goal:

Possible Fallout For the Protagonist if This Goal Is Not Met:

Never being able to reconnect with estranged family members

Sacrificing one’s moral code as one is forced to do dreadful things to survive

Never achieving one’s dreams

One’s self-esteem being forever compromised

Not being able to trust or connect with others

Falling into addiction

One’s existing addiction or mental illness spiraling out of control

Being arrested for breaking the law in order to survive

One’s children never being able to escape the cycle

Being attacked or taken advantage of by others

A shortened lifespan due to illness and a poor quality of life

Death

Clichés to Avoid: the homeless person who fails in his goal but teaches others some meaningful lessons about life along the way

Click here for a list of our current entries for this thesaurus, along with a master post containing information on the individual fields.

June 1, 2017

Theme: The Marrow of Your Story

If structure is the bones of story, theme is the marrow.

Plainly defined, theme is what our stories mean, and it is revealed through other literary elements such as character, plot, dialogue, perspective, setting, mood, and tone. Stories may have several themes. Oftentimes readers—and writers caught off guard—express themes as single-word motifs or a phrase that refers to philosophical-sounding concepts. Sometimes themes are so implicit, even the writer isn’t much aware of them. Other times, they are wonderfully obvious, such as when several characters in Moulin Rouge (2001) sing “Freedom! Beauty! Truth and Love!” to The Green Fairy. Throughout the film, different characters treat viewers to bittersweet dollops of “The greatest thing you’ll ever learn is just to love and be loved in return.” The themes of Moulin Rouge include the supremacy of love, the breaking down of social and economic barriers, and the freedom to self-determine one’s own fate.

What readers, writers, critics, philosophers, agents, publishers, and English Teachers Everywhere know is that theme strengthens story. Without a strong theme, a story tends to lack cohesion, characters act inconsistently, and conflict diminishes. Themes unify the elements of our stories into a meaningful narrative experience. Stories with strong themes provoke emotional and empathetic responses. They remain with us; we think about them long after we have experienced them: “Freedom! Beauty! Truth and Love!”

When I think about theme it is often paired with memories of filling blue essay books in my high school English classes with phrases like “love endures all things” or “the loss of innocence” or, more ambiguously, “man versus nature” in an effort to capture the essence of a canonical work. This is not an uncommon memory, and it is not a useless exercise. Many of us know what themes are, at least vaguely, because of this kind of reductive work. A friend of mine must have had a superb English teacher, because when she recalls her high school English class, she smiles and says with a sense of fondness that she “loved writing themes.” She is a cartographer, not a novelist—yet.

I like to think about theme as the worldview among the characters in a story. This worldview is the ideas and meaning they carry with them throughout the story. Inevitably, worldviews are going to clash with the worldviews of other characters or story elements—if we want to create conflict. When JK Rowling formed the four Houses of Hogwarts, she created a society based on four worldviews. Within those Houses, there is much room for individualism, but as an author, it was a very handy tool. It permitted her to create strong, deep themes with the latitude for nuance. Ultimately, the worldviews that triumph in our stories, the ones with keen resonance, are the ones that obtain enduring meanings.

How Do We Identify Theme?

[image error]We can discover or design theme, or if you are a writer like me, it’s something you manage during revision. You’re writing along or thinking about your story or in an editing phase, and Lo! There’s theme. It’s another one of those things I tend to write down on my editing list to check off, because I don’t really think about it, or rather it’s all I think about on the idea level when I’m first thinking about a story. Theme lingers underneath the surface when I’m thinking about other aspects of story, like character, plot, conflict and setting.

If theme doesn’t come naturally as you’re writing, here are some areas to explore to help bring those ideas to the surface.

Ask: “What is my story about?” Write down the first words and phrases that come to mind. Another way to think about theme is the age-old question since before Aesop: “What is the moral of my story?”

Understand the relationships among motifs, symbols, topics, and themes:

A motif is a recurring idea or concept that develops and reinforces theme.

A symbol is an object or thing that represents something else, including ideas, concepts, moods, and emotions. Symbols reinforce motif.

A topic is the subject matter with which a piece of writing is concerned.

A theme is how meaning is conveyed through the exploration of a topic along with elements such as motifs and symbols.

For example, in Jayne Eyre, fire is one of many motifs that recurs in different ways throughout the novel. There is the lack of fire and warmth when she is a child, both at Gateshead Hall and at Lowood Institute. This motif comes to symbolize a poverty of circumstance and emotion when she is a scorned and neglected orphan. The motif is further embodied in Jayne’s spirited, impassioned personality. Fire also symbolizes illumination, purification, and destruction. As a governess, Jaye explores Thornfield Hall by candlelight, the truth of her employer’s secret concealed in its shadow. Jayne saves Mr. Rochester from burning alive, and ultimately, it is Bertha’s destructive, purifying fire that aids Jayne in obtaining her ultimate desire. These motifs and symbols strengthen and develop some of the themes of Jayne Eyre that include the struggle between our desire and our duty when they conflict, the different moral expectations that apply to caste and gender in Victorian England, and above all, love and passion in its many forms.

Know Your Character’s Worldview: Characters reveal theme and worldview through actions, gestures, and dialogue (what they say and don’t say), what they wear, how they behave, what their secrets are, what they reveal to themselves and others. Forrest Gump is famous for one unforgettable thematic line: My momma always said, “Life was like a box of chocolates. You never know what you’re gonna get.” This is my preferred way to go about identifying theme. Ask yourself: “What is the worldview of my characters/story? What wins out in the end?” If you can boil your character’s worldview down to a simple sentence or two, you’ll have a starting point for theme in his or her story.

For more help identifying your theme, try word mapping or word association. Write down a list of five words from your story. Use each word in a phrase that refers to an essential or existential idea: the big ideas having to do with human nature.

Here are some links that will remind you of some familiar themes:

One Stop For Writers’ Symbolism and Motif Thesaurus

Vehicles For Delivering Theme in Fiction

Symbolism: Symbols typically emerge organically in a work but sometimes not as often as a writer would like. During revision, pay attention to the symbols that are revealed in your story. What colors dominate, which objects are more noticeable than others? What actions do characters perform with more of a sense of significance than others? Are there seemingly mundane objects that make you think of other aspects of the story?

Repetition: the repetition of concepts, gestures, symbols, settings, phrases, or words indicate their significance in the story—they shouldn’t be distracting to the reader but should contribute to the overall thematic pulse of your work. Forrest’s box of chocolates, along with the recurring drifting feather, reinforce the theme of destiny—that life is a big collection of surprises that happen regardless of the person’s actions.

Setting: the setting can reinforce your theme or highlight it. Are you writing about revenge and the promise of its satisfaction as well as its pitfalls? Or how about good luck always running out? Observe how these kinds of stories work very well set in oppressive but stark settings like southern California or the bleak winters of Montana. Change your setting to experiment with how it strengthens or weakens your theme.

Contrast: This descriptive technique involves placing elements in opposition to one another in order to form a distinction. This can be accomplished with characters, values, setting, concepts, ideas, and even on the symbolic level. Going back to Forrest Gump, Forrest’s idea that life is a series of random coincidences is sharply opposed by Lieutenant Dan’s belief that everyone has a destiny. Differences can show competing themes.

Title: you can hint at or give away a great deal thematically in your title: The Age Of Innocence, All The Light We Cannot See, The Virgin Suicides, The Handmaid’s Tale, The Heart Of Darkness,Beloved.

Theme is one of the most misunderstood elements of writing, but when it comes to making your story resonate with readers, it can be one of the most important. Hopefully these tips will help you if you’re struggling in this area. If you have any suggestions for how you figure out the theme in your story, please share them in the comments.

[image error]April has a Master’s in Ethics from Yale University and studied Philosophy and Theology as a post-graduate scholar at Cambridge University. Her fiction has appeared in many literary magazines and has been nominated for the 2015 Best of the Net Anthology as well as the 2017 Pushcart Prize. She is the Associate Editor for Bartleby Snopes Literary Magazine and Press and the Founder and Editor of Women Who Flash Their Lit. Find out more about April here, visit her website, and catch up with her online.

May 30, 2017

What American Horror Story Taught Me About Anti-Heroes

Every time I search Netflix, Hulu, or primetime TV for a new show to watch, I’m convinced that anti-heroes are taking over the world. Breaking Bad, Sons of Anarchy, the Sopranos, Nurse Jackie, Dexter—all popular shows with a less-than-traditional protagonist. The anti-hero seems to be here to stay, so as writers, we should know how to identify and write them. Kathy Edens is here with some tips on how to do just that.

Protagonists of yore were inherently good, and villains were bad through and through. Remember Dudley Do-Right, Canadian Mountie, who was constantly rescuing the damsel in distress from the purely evil Snidely Whiplash?

For today’s readers, though, the hero can be too predictably good. We want characters designed after real-life people. We want to see that they have both dark and light inside, and that they’re not always the good guy.

Differences Between an Anti-hero and a Hero

An anti-hero is a much more nuanced protagonist with faults, foibles, and a dark side that goes against the grain of societal norms, morals, or just plain kindness. Anti-heroes are always deeply flawed. With contradictory traits, they are crafted after real people, unlike a hero who is sometimes too good to be true.

On the flip side, the classic hero is the main character who embodies the notion of “good.” A hero has exemplary morals and never veers from that code. While her may experience failures throughout the story, he will always overcome evil in the end. Consider Hercules as the manifestation of a hero.

To fully appreciate the anti-hero protagonist, it’s helpful to examine one in action. This is where American Horror Story’s third season, “Coven,” comes in. If you haven’t seen it yet, it’s full of witches, voodoo, and racism. These people are, for the most part, evil. But we’re meant to see them in a sympathetic light based on their past and a little light of hope we see inside them.

The main character, Fiona, is a supreme witch. She’s in charge of the coven, but she got to this exalted position through some very nefarious means. As you follow Fiona through the episodes, you see her as conniving and manipulative. And that is juxtaposed with scenes of incredible compassion and warmth, such as when she brings a stillborn baby back to life in the arms of its distraught mother.

The interesting thing about Fiona is that she’s aging and we find out she’s riddled with cancer. As the cancer eats away her body, what little bit that was good inside her gets eaten, too. By the end, you’re rooting for her demise.

The suspense is high in American Horror Story Coven as all of the witches use their incredible powers for good and evil. People are killed, then brought back to life, and there is a civil war between the voodoo priestess and the coven, not to mention an evil racist who tortured blacks in the time of slavery. It’s some pretty heady anti-hero stuff. Just when you start to think they have some redeeming qualities, someone else dies, and you realize they’re only in it for themselves. The beauty of Coven is that you don’t know until the end which anti-heroes have redeeming qualities and which are purely evil.

[image error]

Pixabay

How To Create Three-Dimensional Anti-Heroes

An anti-hero is not simply a person with some major faults. There’s pathos involved, maybe a little psychosis, and usually a self-concept that is inflated and complicated. When you create your anti-hero, consider that they’re usually:

Not very good role models. We wouldn’t want to be like the witches in Coven (though sometimes it would be fun to kick butt like they do).

Somewhat selfish but can display good traits now and then.

Mainly motivated by self-interest. They do whatever it takes, sometimes crossing lines that others wouldn’t dare.

Motivated by conflicting emotions. One minute they’re intent on revenge and the next they’re doing something honorable.

More inclined to choose a wrong action because it gets them what they want quicker.

Display compassion for the underdogs, children, or weak and infirm characters.

They don’t apologize for their bad behaviors.

Chock full of contradictions.

One caveat when creating your anti-hero: he or she doesn’t always have to be redeemed by the final page. Some anti-heroes, while showing streaks of compassion and caring, are still damaged people at the end of a story. They’re characters we love to hate.

So watch American Horror Story to get an idea of carefully crafted anti-heroes. Or better yet, watch the movie Suicide Squad. Even Homer Simpson is a fully-realized anti-hero. Pay attention to how other successful writers create an anti-hero, and then let your imagination go to town.

Who are your favorite anti-heroes? Let us know in the comments below who your favorite anti-heroes are. Let’s start a resource list of great examples that we can refer to and learn from.

Kathy Edens is a staff writer at ProWritingAid.com, the most comprehensive editing tool that helps you polish and sharpen your writing through readability analyses and technical edits reviews. Check out the free online editing tool that turns your good writing into great content.

May 27, 2017

We’re In This Together: How To Help Other Authors Succeed

A common query Becca and I get is, “Why do you do what you do?” It’s a fair question, because in order for us to coach writers through our books, speaking, and our One Stop for Writers site, we’ve had to temporarily put our fiction-writing on hold. Not an easy decision. But the fact is we love to see dreams realized. This is why we do it. As writers ourselves, we know the power of THIS particular dream–a book in hand, our name paired with the title, and the knowledge that readers are losing themselves in a world we’ve created.

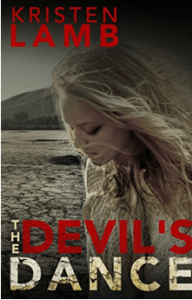

We celebrate each time someone we know achieves this dream–and how could we not? It’s so wonderful to see all that hard work pay off! Today, we are celebrating because our friend Kristen Lamb has just released her first mystery thriller, The Devil’s Dance.

Many of you know Kristen and the giant heart she has for writers. She has such passion for those of us in this industry and gives her all every day through her blog and the relationships she builds. So when someone so authentic and genuine rounds the fiction horn, well, we can’t help but cheer especially loud!

Many of you know Kristen and the giant heart she has for writers. She has such passion for those of us in this industry and gives her all every day through her blog and the relationships she builds. So when someone so authentic and genuine rounds the fiction horn, well, we can’t help but cheer especially loud!

I’ve been away the last month in Italy, but the book is on my kindle now and I can’t wait to read it. I hope you’ll check it out too. But first, let’s look more at book releases in general and talk about what we can do to help the authors we know.

Launching a Book: Behind the Scenes

When an author releases a book, it’s all smiles and excitement…on the outside. What we don’t see is the anxiety going on within: will this book find its readers? Will it become lost in the glut of fiction available? If I share my excitement too freely, will people see it as unwanted promotion?

These worries are universal among authors. And, with the saturation of promotion these days, it’s important we don’t push a book too hard ourselves. Inside, we hope others will step up and help.

(And BOOM, this is what community is about, right? Stepping up!)

So if you know an author like Kristen who is releasing a book and you want to help, here’s a few things you can do (beyond the obvious of purchasing the book).

1: Ask your local library to bring the book in. Many libraries have an online form and they often pay attention to requests. Click here to find a library near you…and why not request Kristen’s book while you’re at it?

May 25, 2017

Why You Should Never, Ever Go On a Destination Writing Retreat

So last week, Tim Raveling was here to let us know the what, where, and why of writing residencies. There are definitely a lot of options, but imo, one of the best destination writing retreats to attend is one where Angela Ackerman is speaking. I know, I know. Sounds like a pipe dream. But…Ange is going to be speaking at an amazing retreat coming up—one that has the word CRUISING in the title. Can you believe it? Well, read on, naysayers, because Christina Delay is here to share (in her own personal and beautifully snarky way) about this opportunity.

You’ll hear from loads of people why you should travel and go on writing retreats. There are lists, like The Case for Writing and Travel, that say why travel is super-important to writing. But there’s another side to this story. I’m here to reveal to you why you should never, ever go on a destination writing retreat. Especially not a Cruising Writers Writing Retreat.

[image error]Your Comfort Zone Will Be Tested

Leaving the cozy space of our comfort zone and traveling by plane, train, or cruise ship has the same feeling as starting a new school or a new job. Wouldn’t it be easier to stay at home, doing the safe thing and living within the known and explored shelter we’ve built for ourselves?

Because if we leave that comfort zone, the one that we know every nook and cranny of, we’ll have to enter a new space. A space where our comfort zone is not allowed.

There will be a different culture there in that space, maybe a different language. The food may not be what we’re used to. And the experiences we come across may not be what we expect. Surprises most certainly await us, if not around every corner, then at each new cruise port or country.

It’s definitely safer to stay at home, surrounded by the sounds and smells that we’ve known for years. Never mind that creativity is driven by new experiences and fresh senses. Is that burst of creativity and unlocking of the elusive muse really worth the leap into the unknown?

You’ll Change

“I am not the same, having seen the moon shine on the other side of the world.” – Mary Anne Radmacher

It’s been proven that change is one of the scariest things out there. And it’s also a fact that travel changes us. We cannot come home the same person again. Once a thing has been seen or heard or experienced, it cannot be undone. Traveling will broaden your world perspective.

Not only that, but your writing will change when traveling with Cruising Writers on a writing retreat. It will be influenced by world-renowned craft teachers like Lisa Cron, Angela Ackerman, and Margie Lawson. You will grow your writing tribe by meeting other retreaters who, like you, have bravely left their comfort zone. And you may make lifelong friends or add a new critique partner to your repertoire.

So if what you’re wanting is for everything to stay status quo, a destination writing retreat is the last thing you should do.

Old Ideas Will Be Challenged

On a writing retreat, you’ll be introduced to new writing craft tools that may challenge what you’ve used in the past. Marketing strategies from bestselling authors that are contrary to what you’ve tried may be tossed around.

With Cruising Writers First Pages Readings, an editor and an agent will challenge your first page, telling you what works and what doesn’t…and it may lead to revisions that you had never before considered. Brainstorming is also a common side effect of getting together with a group of writers. New ideas and plot problems are tossed around and worked out.

But all of that takes courage to face and to participate in. If you like your old ideas, your same-ole way of doing things, and your current marketing tactics, then never, ever go on a destination writing retreat.

Your Writing Career May Never Be the Same

Going on a writing retreat will open you up to new career opportunities and new professional connections. It could be the link that you need to take your career to the next level.

BUT…

There’s that whole fear of success thing a lot of us have. And if that’s you, certainly NEVER, EVER go on a writing retreat. Because you will be exposed to influential people who are serious about writing, and they will remember you.

At Cruising Writers, our retreats are kept small on purpose so you have the opportunity to make lasting connections. Because of this, you may develop a relationship with the agent and editor that travel with us; on our September cruise, that will be Michelle Grajkowski (agent and president of Three Seas Literary) and Deb Werskman (editor with Sourcebooks). More than a pitch session, you’ll see them every night at dinner, possibly on shore excursions, in workshops, at the spa, on the walking deck, at the casino, etc. And with less than 30 other writers on the trip, you’ll have to talk to them before you pitch to them.

[image error]“Cruising Writers is an amazing opportunity to improve your craft with top-notch teaching sessions. The small group format allows you to get to know your fellow authors as well as the guest speakers, editors, and agents. Through the contacts I made on this cruise, I was able to sign with a well-respected agency that I had on my wish list for several years. Go. Take the cruise. You won’t be disappointed.” – Vicki Tharp, Author

If you’re not ready to launch your career or take the next step on your writing journey, then stay in your comfort zone. You won’t be disappointed.

But neither will you grow or be surprised.

[image error]Christina Delay is the hostess of Cruising Writers and an award-winning author represented by Deidre Knight of The Knight Agency. When she’s not cruising the Caribbean, she’s dreaming up new writing retreats to take talented authors on or writing the stories of the imaginary people that live in her heart.

Cruising Writers brings aspiring authors together with bestselling authors, an agent, an editor, and a world-renowned writing craft instructor together on writing retreats. Cruise with us to Grand Cayman this September with Lisa Cron (author, Wired for Story and Story Genius), Angela Ackerman (co-author, The Emotion Thesaurus), Michelle Grajkowski (agent, Three Seas Literary), and Deb Werksman (editor, Sourcebooks).

May 23, 2017

Three More Lesser Known Archetypes

Back in January, Jonathan Vars was here to talk about some lesser-known archetypes and how utilizing them can bring a sense of freshness to our stories. Because of the positive feedback on that post, he’s back with three MORE archetypes you might not be so familiar with.

As I mentioned in my original post, there are dozens of character archetypes available to the fiction writer. Having a broad range of character types is like having a palette of different colors to paint with. Each archetype offers a different perspective and point of view. They provide unique insights into your story that you would be unable to achieve by clinging only to the “tried and true” characters. So, without further ado, here are three more lesser-known archetypes to use in your writing:

The Penitent

The literal meaning of penitent is “sorrowful or regretful.” So the penitent is that character who’s seeking cleansing, forgiveness, and redemption from a dark past. One of the best examples of this that I’ve seen in modern writing is the character of John Reese from the TV show Person of Interest. Reese’s somewhat jaded past in espionage leaves him with many regrets that haunt him throughout the show.

The penitent is interesting because his guilt can serve both as a motivator (spurring him on to seek cleansing) and an Achilles heel (leaving him vulnerable to self-doubt and feelings of unworthiness). Any time a character can embody this sort of dual nature, it adds depth, both to his personality and the story as a whole.

The Curmudgeon

[image error]The curmudgeon is essentially the “cranky old man,” the cynical character who seems happiest when bemoaning imperfections. Curmudgeons are versatile in that they can play just about any story role—antagonist, sidekick, mentor, jester, even villain. Ebenezer Scrooge, everyone’s favorite Christmas hater, is the perfect example of this.

Though seemingly one sided, this archetype can be used to represent many different points of view, depending on the depth of character established. Although crusty and probably not much fun to be around, the curmudgeon can add realism to a story, reminding overly optimistic characters of stark realities and potential problems. The curmudgeon can also become a sympathetic character when readers learn the backstory responsible for his or her negative point of view.

The Sycophant

The sycophant is the quintessential “yes man”, the underling who goes along with whatever their superior says in a constant effort to maintain approval. Sycophants are generally portrayed as somewhat mindless, accustomed to taking orders instead of thinking for themselves. A comical example is Lefou from Disney’s Beauty and the Beast. Despite being insulted and physically beaten by Gaston, Lefou remains devoted and eager to please, playing perfectly into this archetype.

Historically, the sycophant doesn’t have much of an arc, being used mostly to define other characters. Bring him to life by probing deeper into his background and making him more than just a subservient sidekick. An interesting concept is the idea of a pseudo-sycophant who poses as a “yes man” while secretly plotting against the hero in the background. By making him a unique and three-dimensional character in his own right, the sycophant can be used to provide singular insight, add tension and conflict, symbolize a larger idea or theme of the story, or act as a foil or mirror to the protagonist.

While archetypes are known for being certain kinds of characters, they don’t have to be etched in stone. Give them depth and add individualization by mixing them up. Who says you can’t have a penitent with sycophantic tendencies? Or a curmudgeon hiding his penitent roots? People are dynamic, and your characters should be as well. Applying human complexities to our characters can result in truly original characters that will greatly enhance your story and cast.

[image error]Jonathan Vars is a Christian fiction writer from New England, founder of the writing website voltampsreactive.com. His work in literary analysis of classic films and literature has been published by academic websites and he is the author of the soon to be released novel “Like Melvin” for which he is currently writing a sequel. In addition to writing, Jonathan enjoys running, painting, and trying not to freeze to death in the winter. He is currently willing to consider guest blogs for his website.

Writers Helping Writers

- Angela Ackerman's profile

- 1014 followers