Ann Marie Ackermann's Blog: Ann Marie Ackermann's Historical True Crime Blog, page 2

June 20, 2017

Greengages: Mark Twain and the Sweetest Fruit of Germany

A bowl of greengages.

He put up a fine luncheon for us and added to it a quantity of great light-green plums, the pleasantest fruit in Germany…. Mark Twain, A Tramp Abroad

Greengages

Anna Pavord, writing for the British newspaper Independent, calls them “most ambrosial of all tree fruit.”

David Karp describes them as “the best fruit in the world” in the New York Times.

Mark Twain traveled to Germany in 1878 and tried them at his hotel in Heilbronn, where he dubbed them the “pleasantest fruit in Germany.”

With respect to sweetness, all three authors have a point. Greengages taste like honey. Long considered one of the sweetest fruits, the green plums enjoy a delectably “noble” reputation in Germany. Germans call them the “queen of the plums.” David Karp measured their sugar content in France with his refractometer and obtained a value, 30.5, that nearly went off the scale.

Greengages on a branch.

Hard to grow

You’ll have a hard time finding fresh greengages in America. They’re difficult to grow. Rain can make them split open. It’s expensive to pick the fruit. And they don’t produce regularly – greengage trees will sport a bumper crop one year and the next, for no apparent reason, grow only a few plums. And to make it worse, you should really leave them on the tree until they’re ripe. They taste best fresh off the tree.

Popular in Europe, but not America

Greengages originated in the Middle East. France has had them since the 15th century. In both Germany and France, the fruit is named after Queen Claude (d. 1524): Reine-Claudes, Reineclaude, or Reneklode. She must have liked the light green plums as much as Twain did.

The fruit came to England in the 17th century. The man who introduced them, Sir William Gage of Suffolk, also lent them his name.

Greengages were once popular in the United States, but farmers found them too difficult to grow. They have almost vanished from the American orchards and tables. Across the ocean, however, greengages surfed a juicy wave of popularity in the 19th century – at the time Mark Twain tried them in Heilbronn. In fact, German markets of the 18th century often forbade all other plum varieties outside of greengages and mirabelles. The other varieties were thought to be unhealthy.

Greengages. Photo from Pixabay, with permission.

Pleasantest fruit of the summer?

Summer begins this week, and after that the plum season will soon be upon us. Keep your eyes open for the queen of the plums at the marketplace and offer yourself a treat Mark Twain once enjoyed. One taste might transport you to ambrosial heaven.

Have you ever had the opportunity to try a greengage? If so, what did you think of the taste?

Literature on point:

Karl Günther Barth, “Die Königin der Pflaumen – ein fast vergessene Sorte,” Hamberger Abendblatt (2 August 2014).

Rudolf Habs & L. Rosner, Appetitlexikon (Insel Verlag 1982).

David Karp, “A Finicky Fruit Is Sweet When Coddled,” New York Times (1 Sept. 2004).

Anna Pavord, “Plum job: A juicy guide to greengages and plums,” Independent (12 August 2011).

“Reineclaude,” Lebensmittel Warenkunde (2017).

Reneklode aus Oullins, Manufactum

Mark Twain, A Tramp Abroad, ch. 14 (public domain).

The post Greengages: Mark Twain and the Sweetest Fruit of Germany appeared first on Ann Marie Ackermann's author website.

June 8, 2017

Mark Twain’s “A Dying Man’s Confession”: Truth or Tall Tale?

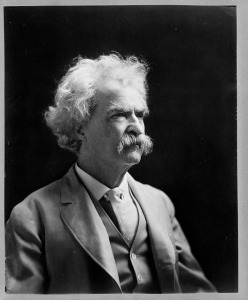

Mark Twain, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, public domain

God! how delicious the memory of it!—I caught him escaping from his grave, and thrust him back into it. – Mark Twain, “A Dying Man’s Confession,” in Life on the Mississippi

Murder and revenge.

These two themes form the warp and weft in “A Dying Man’s Confession,” the most memorable short story in Mark Twain’s Life on the Mississippi. The story spans the globe. It starts a murder in Arkansas during the Civil War and ends in one of the creepiest buildings of Germany history: the Leichenhaus (literally: corpse house) or waiting mortuary. And it contains a forensic method that was very modern for its time.

But are there any kernels of truth in Twain’s story?

A bit of background: the German Leichenhaus

Waiting halls for the dead sprung up throughout Germany in the 19th century, in part due to societal fears of premature burial, and in part due to the medical profession’s argument that decomposition constituted the only sure sign of death. Bodies were laid out in the mortuary halls, in their coffins and covered with shrouds, to await that one sure medical sign before burial. Flowers decked the coffins to offset the odor.

To prevent someone from being buried alive, the mortuary attached rings and cables to the hands of the presumptive dead. If a hand moved, a bell would sound and alert a mortuary attendant, trained to give first aid.

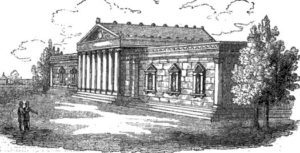

The Munich Leichenhaus. Garner’s Magazine, 1833 (public domain).

Twain in the Munich Leichenhaus

Munich’s Leichenhaus was one of the most famous. Open to the public, it quickly became a tourist attraction. Mark Twain visited on Jan. 4, 1879. His impressions unnerved him:

Toward the end of last year, I spent a few months in Munich, Bavaria…. One day, during a ramble about the city, I visited one of the two establishments where the Government keeps and watches corpses until the doctors decide that they are permanently dead, and not in a trance state. It was a grisly place, that spacious room. There were thirty-six corpses of adults in sight, stretched on their backs on slightly slanted boards, in three long rows—all of them with wax-white, rigid faces, and all of them wrapped in white shrouds. Along the sides of the room were deep alcoves, like bay windows; and in each of these lay several marble-visaged babes, utterly hidden and buried under banks of fresh flowers, all but their faces and crossed hands. Around a finger of each of these fifty still forms, both great and small, was a ring; and from the ring a wire led to the ceiling, and thence to a bell in a watch-room yonder, where, day and night, a watchman sits always alert and ready to spring to the aid of any of that pallid company who, waking out of death, shall make a movement—for any, even the slightest, movement will twitch the wire and ring that fearful bell. I imagined myself a death-sentinel drowsing there alone, far in the dragging watches of some wailing, gusty night, and having in a twinkling all my body stricken to quivering jelly by the sudden clamor of that awful summons!*

The experience sparked a short story.

A Dying Man’s Confession

“A Dying Man’s Confession,” which climaxes in the Munich Leichenhaus, begins in Arkansas during the Civil War. A German on his deathbed, whom Twain supposedly met during his Munich travels, narrates the story. He lived in Napoleon, Arkansas with his wife and daughter during the war. But one night, during a burglary, the narrator was chloroformed and his family murdered. One burglar was missing his thumb and was the nicer of the two. His accomplice committed the murder; the thumbless man could only protest.

The burglary was interrupted when the burglars’ company arrived and the captain asked for water; the burglars left with their comrades. The poor narrator found his wife and daughter murdered – along with an important clue: a piece of paper with a thumbprint in their blood. When the narrator discovered that a Captain Blakely and Company C had come through that night, he decided to track down the murderers.

In disguise as a fortune teller, the narrator followed Company C and found a German private missing a thumb. He started telling fortunes, but required his clients to provide their thumbprints first as means for interpreting their future. By careful comparison, he discovered one print that matched the print from his house. The print belonged to another German private, Franz Adler. The narrator tried to murder him and thought he was successful.

In Munich’s Leichenhaus

The narrator returned to Germany and years later began working as a watchman in the Munich Leichenhaus. There the unconceivable happened.

Two years ago—I had been there a year then—I was sitting all alone in the watch-room, one gusty winter’s night, chilled, numb, comfortless; drowsing gradually into unconsciousness; the sobbing of the wind and the slamming of distant shutters falling fainter and fainter upon my dulling ear each moment, when sharp and suddenly that dead-bell rang out a blood-curdling alarum over my head! The shock of it nearly paralyzed me; for it was the first time I had ever heard it.

I gathered myself together and flew to the corpse-room. About midway down the outside rank, a shrouded figure was sitting upright, wagging its head slowly from one side to the other—a grisly spectacle! Its side was toward me. I hurried to it and peered into its face. Heavens, it was Adler!

Adler had survived the narrator’s murder attempt in Arkansas and had also returned to Munich. The narrator refused all first aid and let Adler sink back and die in his coffin.

He ends his “Dying Man’s Confession” with the observation:

It is believed that in all these eighteen years that have elapsed since the institution of the corpse-watch, no shrouded occupant of the Bavarian dead-houses has ever rung its bell. Well, it is a harmless belief. Let it stand at that.

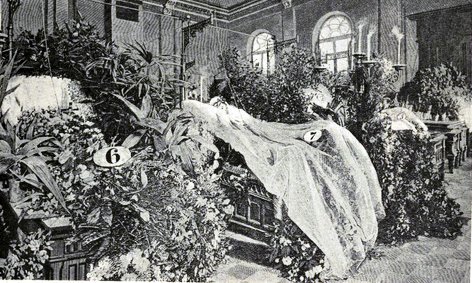

Interior of the Munich Leichenhaus. William Tebbs, Premature Burial and How It Can Be Prevented (1905, public domain).

Truth or Tall Tale?

With Mark Twain, you can’t always tell. Franz Adler and his death in the Leichenhaus are certainly products of Twain’s imagination. But that begs the question of whether any of the bodies in the waiting mortuary ever did come back to life.

Jan Bondeson, a professor at the University of Wales College of Medicine has tracked down stories of premature burial, and in particular, folklore about “resurrections” in the Munich Leichenhaus. He followed the few stories about ringing bells and bodies sitting up in their coffins to their sources, only to find the 19th-century version of fake news.

In the course of the 19th century, how many people did the German waiting mortuaries actually save?

Zero, says Bondeson.

That’s right, none. The 19th-century physician’s diagnosis of death was pretty accurate.

By the 1890s, Germany made the decision to remove the alarm systems from its mortuaries. And we can safely say that Twain’s depiction of Adler ringing his bell crossed the line into the highly improbable.

.

.

May 30, 2017

Lady Lucie Duff Gordon – First Female True Crime Author in English?

A sketch by a school friend of Lucie Duff Gordon, aged 15 (c. 1836, public domain).

A man who murdered his lover on his wedding day. A serial killer who lured girls into his house with the promise to show them their future husbands in a magic looking glass. The first intentional use of a dog to search for a cadaver. Lady Lucie Duff Gordon (1821–1869) translated these stories from German to English and published them in 1846. Her anthology, Narratives of Remarkable of Criminal Trials, includes fourteen stories and her own preface.

And that might make her the first female true crime author in the English language.

Portrait of Engel Christine Westphalen by Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein (1751-1829, public domain).

Engel Christine Westphalen: First female true crime writer in the world

Across the North Sea in Germany, another woman author helped carry the true crime torch. In fact, Engel Christine Westphalen (1758-1840) might have been Lucie Duff Gordon’s role model. Westphalen was probably the first female true crime writer anywhere. She competed in the genre against the famous German poet, Friedrich Schiller, whom scholars today consider a father of modern true crime.

Westphalen, however, raised Goethe’s ire. Johann Wolfgang Goethe (Faust, Sorcerer’s Apprentice, Erlking), a vanguard of Weimar classicism, had laid down some rules for German literature: Fiction was an acceptable topic for female authors, but not true crime. Goethe assigned true crime to the genre of historical tragedy, a male-only genre.

Westphalen broke the rules by publishing a tragedy in 1804 about Charlotte Corday, the murderer of Jean Paul Marat in the French Revolution. When Goethe found out she wrote it, he erupted and took a shot at her underwear. “The worthy author of this tragedy of Charlotte Corday would have better spent her time knitting a warm underskirt for the winter than meddling this drama,” he said. Westphalen ignored Goethe and later won an award for her writing. You can read more about Westphalen and her Corday tragedy here.

Goethe and Schiller. Pixabay.

Brief history of the true crime genre

The true crime genre has French and German origins. Friedrich Schiller (Ode to Joy, William Tell) helped launch true crime as a modern genre. Although he wasn’t the first author to write about crime, crime stories before his time were simple moralistic tales designed to scare the reader from treading from the path of righteousness. Schiller offered something new. Schiller and his French counterpart Gayot de Pitaval offered a psychological analysis of the criminal and focused on the motive. That’s the demarcation that separates modern true crime from the old-fashioned, moralistic crime tales. For that reason, scholars consider Schiller a father of the modern true crime genre.

The Death of Marat by Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825), public domain.

True crime genre in the English language

If you define the true crime genre as a psychological analysis of the offender and his or her motives, the jump from French and German to English came later. Plenty of crime stories appeared in the English literature before Schiller and Pitaval worked their changes, but they appeared in the old-fashioned form of moralistic stories in pamphlets, the penny press, and ballads. Perhaps due to Schiller’s influence, respectable English authors began taking an increasing interest in crime tales. Thomas De Quincy published the satirical Murder Considered as One of the Fine Arts in 1827, Charles Dickens A Visit to Newgate in 1836, and William Thackeray Going to See a Man Hanged in 1840.

I can’t, however, find another female author among them, either in the modern form of the genre or in the older, moralistic one. For that reason, I propose Lucie Duff Gordon as a candidate for the first female true crime author in the English language.

Lucie, Lady Duff-Gordon by Henry W. Phillips (c.1851).

Lucie Duff Gordon

Lucie Duff Gordon (1821–1869) was the only child of John Austin, a professor of jurisprudence at the University of London, and Sarah Austin, a German to English translator. In 1827, Lucie’s family moved to Germany so her father could study the German literature on jurisprudence. She attended a German school and became fluent in the language. It’s quite possible she became acquainted with Engel Christine Westphalen’s works in Germany.

Lucie became an avid reader, and following her return to England, she always read books with an eye towards the possibility of translating them. In 1840, she married Sir Alexander Cornwall Duff Gordon. Around the same time, Lucie Duff Gordon started publishing her first translations. Her fourth translation was the Narrative of Remarkable Criminal Trials.

Narrative of Remarkable Criminal Trials

The Narrative was Lucie Duff Gordon’s anthology of crime stories from the Bavarian judge and legislator, Paul Anselm Ritter von Feuerbach. Feuerbach spearheaded the legislative reform to repeal Bavaria’s version of the Constitutio Criminalis Carolina, a 300-year-old criminal code of the Holy Roman Empire. Bavaria passed Feuerbach’s new criminal code in 1813. Much of Germany later followed suit, basing their new codes on Feuerbach’s reform.

In her preface, Lucie Duff Gordon praised Germany’s criminal justice system. She suggested that Bavaria’s slow and thorough approach to trials resulted in lower rate of false convictions of innocent men than in England. The English, she suggested, would be wise to look across to the continent and learn something from the Bavarians.

Lucie Duff Gordon went on to write and publish her own works. Her most famous were Letters from Egypt (1865) and Last Letters from Egypt (1875).

Do you know of any female true crime authors in the English language prior to 1846? Knowledge is a cooperative effort, and perhaps a reader knows of another author.

Literature on point

Pamela Burger, “The Bloody Origins of the True Crime Genre,” JSTOR Daily (August 24, 2016).

P.J.A. Feuerbach, Aktenmäßige Darstellung merkwürdiger Verbrechen, (Giessen: Heyer, 1828).

Lady Duff Gordon, Narrative of Remarkable Criminal Trials (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1846).

Gail K. Hart, Freidrich Schiller: Crime, Aesthetics, and the Poetics of Punishment (Newark: University of Delaware Press 2005)

Jeffrey L. High, Schiller’s Literary Prose Works: New Translations and Critical Essays (Rochester, New York: Camden House 2008)

Stephanie Hilger, “The Murderess on Stage: Christine Westphalen’s Charlotte Corday (1804),” in Women and Death 3: Women’s Representations of Death in German Culture since 1500 (Clare Bielby & Anna Richards, eds.) (Rochester, NY: Camden House 2010) 71-87.

U.S. National Library of Medicine, “Most Horrible and Shocking Murders: True Crime Murder Pamphlets” (2010).

Gordon Waterfield, Lucie Duff Gordon in England, South Africa and Egypt (E.P. Dutton & Company, 1937).

The post Lady Lucie Duff Gordon – First Female True Crime Author in English? appeared first on Ann Marie Ackermann's author website.

May 16, 2017

Consitutio Criminalis Carolina: Your Rights in a Torture Chamber

Time. Image from Pixabay.

The dangers of time travel

You have to admit you’ve at least thought about it before. What would it be like to fly back in time with a time machine?

What would you want to see? The dinosaurs? The life of Jesus Christ? A historical event you’ve been researching and have lingering questions about?

No matter which trip you select, it would be fraught with danger. The dinosaurs might snack on you. You could get caught in a war. If you plan to visit Renaissance Europe and walk around in your jeans and T-shirt, snapping pictures with your cell phone, you can plan on getting arrested. And in case you get marched into the torture chamber, you probably have no idea what your rights would be.

So just in case you find a time machine in grandpa’s attic and contemplate a trip back a few centuries in time to Europe, you’ll want some advice about the legal system – and your legal rights in the torture chamber.

I’m here to help you.

Stylized steampunk metal collage of time counting device. (c) donatas1205, via Shutterstock.com.

Judicial torture

First, some basic concepts.

Judicial torture – that means torture as a method of collecting evidence and not as a method of punishment – grew out of the Greek and Roman legal systems. By 1252, Pope Innocent IV approved its use in Roman-canon law. That meant it could be used in church procedures (think Inquisition).

When you set the dials on your time machine, your best country to visit, from a judicial perspective at least, would be England. Of all the European countries, England did not adopt Roman-canon law. Instead, it used a jury. Although the English juries evolved over time from investigating bodies to the modern juries we know today, they avoided the judicial torture of continental Europe. In all probability, the members of your English jury would figure out how to turn on your cell phone and get the fright of their lives. But they couldn’t put you on the rack to find out more about it.

As more modern legal systems began to replace the trial by ordeal in continental Europe, judicial torture found acceptance. In fact, people may have found torture not very different – or even a step up from – the medieval ordeals. Trial by ordeal was an ancient religious-judicial procedure to let God decide the case. It meant subjecting the suspect to a dangerous event, e.g. submersion in water. The court interpreted the suspect’s survival as God’s intervention to prove their innocence. Roman-canon law, then, represented an improvement. It increased your chances of surviving a trial.

Torture chamber with rack. (c) Ozgur Guvenc, via Shutterstock.com.

Constitutio Criminalis Carolina

Now set the location dial on your time machine to the Holy Roman Empire and the year to 1532. That’s when Emperor Charles V enacted the Constitutio Criminalis Carolina, landmark legislation for criminal law. How is it that this statute, with an awful reputation so often associated with witch trials, actually advanced individual rights?

The Constitutio Criminalis Carolina incorporated many facets of Roman-canon law, but went ever further in balancing the state’s need for an investigation against individual rights. For the first time, a suspect in a criminal investigation had at least some rights against the excesses of the judicial system. The Constitutio Criminalis Carolina also contained some seemingly modern insights – it was the first law to distinguish between first and second-degree murder.

One small stroke from Charles’s pen, one giant leap for individual rights.

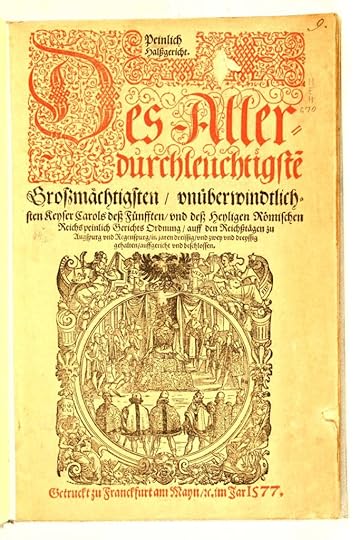

Constitutio Criminalis Carolina. Cover page to a 1577 edition. Imprint: Frankfurt am Main, Johannem Schmidt. Verlegung Sigmund Feyerabends, 1577

By amtliches Werk (Scan from the original work) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Your rights under the Constitutio Criminalis Carolina

So what would have happened if you started walking around the Holy Roman Empire, snapping pictures, and got arrested? Here’s a small litany of your rights.

No torture without probable cause.

There had to be sufficient suspicion against you before the state could torture you for evidence. A “half-proof” was usually required. That meant half the evidence required to convict you. For example, the Constitutio Criminalis Carolina required two eyewitnesses or an eyewitness and a confession as full proof, so one eyewitness who claimed you committed the crime counted as a half proof and counted as probable cause for judicial torture.

No leading questions! (c) Everett Collection, via Shutterstock.com.

No leading questions.

Leading questions in the torture chamber can lead to false confessions. Charles V recognized that as early as 1532. So the Constitution Criminalis Carolina banned leading questions. An interrogator could ask what kind of weapon was used in a murder, but not if it was a knife. He could ask where the body was hidden, not if it had been dumped in the local mill pond. And he could ask what your cell phone is supposed to do, but not if it’s an instrument of witchcraft.

The interrogator tried to elicit information only the perpetrator could know – a technique used today in modern law enforcement to weed out false confessions – and leading questions only got in the way.

Of course, it was difficult to enforce the rule. But many in many cases, the court gave the interrogator written questions ahead of time. And since the Carolina also required witnesses to be present in the torture chamber, it might have been more difficult to get around the prohibition against leading questions than many assume.

Corroboration of a confession.

Even if you did confess, the court couldn’t use that against you without corroboration. Pain might lead a witness to say anything. So if you confessed to something specific only the perpetrator could know, let’s say dumping a body in the local mill pond, the court would require the investigator to check it out.

That’s exactly what happened in a murder-robbery case in Germany’s Rhine Valley in the 18th century. When an accessory to the crime reported that the principals dumped the body in a pond, the investigators were required to dredge it. They couldn’t find the body. Normally, then, there wouldn’t have been enough evidence to convict the accessory. In this case, the court did convict the accessory but based on other evidence.

Compensation if tortured illegally.

Here’s a good one. If you could prove you were examined under torture in violation of the law, you were entitled to compensation. Section 20 allowed you to sue the officials who tortured you illegally. Section 20 also eliminated any defense on the officials’ part based on your having waived your rights.

Safe time traveling

Of course, I hope you’re never subjected to torture and that you enjoy your time travels without any legal entanglements. Despite its advances in individual rights, the Constitutio Criminalis Carolina remains abhorrent for its use of torture. Thankfully, Europe abolished torture by the beginning of the 19th century.

The assassination in my book offers some interesting time traveling in this respect. The Kingdom of Württemberg, where the murder took place, abolished torture in 1811. The murder was in 1835. But Württemberg didn’t get around to abolishing the Constitutio Criminalis Carolina until 1839! That means the assassination in my book was one of the last great crimes investigated under the centuries-old law. And it also means that the investigator had to try to prove the case under the old evidentiary system of proof requiring two witnesses or one witness and a confession. Württemberg didn’t recognize circumstantial evidence until 1839 when it adopted a new criminal code.

No wonder, then, that the solution to this case came from America!

You can pick up my book, Death of an Assassin, and enjoy some safe time traveling. And I promise the dinosaurs won’t eat you.

Prehistoric times. Image from Pixabay.

Literature on point:

Clemens-Peter Bösken, Das Ende der grossen rheinischen Räuber- und mörderbande: Der Düsseldorfer Sicehenprozess von 1712 (Erfurt: Sutton Verlag, 2011).

Constitutio Criminalis Carolina (partial translation)

John H. Langbein, Prosecuting Crime in the Renaissance: England, Germany, France (Harvard Univ. Press, 1974).

John H. Langbein, Torture and the Law of Proof: Europe and England in the Ancien Régime (Univ. of Chicago Press, 1977).

Wolfgang Schild, “ ‘Von peinlicher Frag’: Die Folter als rechtliches Beweisverfahren,” Schriftreihe des mittelalterlichen Krimminalmusuems Rothenburg o.d.T., Nr. 4 (1999).

The post Consitutio Criminalis Carolina: Your Rights in a Torture Chamber appeared first on Ann Marie Ackermann's author website.

May 9, 2017

Dorothy Kilgallen: Crime Reporter as a Murder Victim?

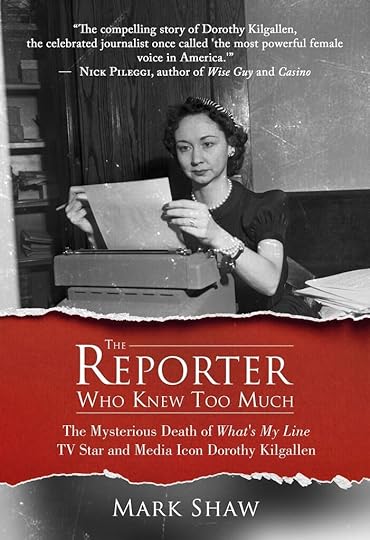

Mark Shaw’s book on the mysterious death of Dorothy Kilgallen.

The night before she died, Dorothy Kilgallen participated in the television show “What’s My Line” and correctly guessed the contestant’s occupation. The young woman sold dynamite.

Kilgallen, a crack investigative and crime reporter, was sitting on a stack of dynamite herself – her research on the JFK assassination. Before the new day broke, it cost Kilgallen her life. That’s what Mark Shaw thinks. He recently published a new book, The Reporter Who Knew Too Much: The Mysterious Death of What’s My Line TV Star and Media Icon Dorothy Kilgallen. Based on several years of research, the book offers new evidence that’s never been revealed before.

Finally, an investigation – 51 years later

Did DorothyKilgallen’s knowledge of the JFK assassination lead to her murder? Shaw’s book has convinced the Manhattan DA’s Office to open an investigation into Kilgallen’s death – 51 years later!

Mark Shaw joins us today to tell us why.

A former criminal defense attorney and legal analyst for CNN, ESPN, and USA Today for the Mike Tyson, O.J. Simpson and Kobe Bryant cases, Mark Shaw is an investigative reporter and the author of 20+ books whose latest is The Reporter Who Knew Too Much. You can learn more about the book by clicking on the book title or watching Mark Shaw’s book-signing presentation.

Welcome, Mark Shaw!

Most people know Dorothy Kilgallen as a “What‘s My Line” panelist, but she was equally well known as a crack investigative and crime reporter. What famous crimes did she cover?

18 Nov 1954, Cleveland, Ohio, USA — Original caption: Newsman gather around Wm. J. Corrigan at the courthouse today to discuss the Sheppard trial. Dorothy Kilgallen (L) seems to be doing most of the talking. Woman in the center is unidentified. — Image by © Bettmann/CORBIS; courtesy of Mark Shaw.

In addition to her What’s My Line? fame, Dorothy covered many of the most famous criminal cases of the 29th century, the Lindbergh baby kidnapping case, the Profumo Scandal in England, the Dr. Sam Sheppard murder trial, the Lenny Bruce 1st Amendment case and most importantly, the Jack Ruby trial.

Her columns won her a few significant enemies….

Dorothy was a woman of the truth and her New York Journal American column, syndicated to more than 200 newspapers across America, could make or break the career of a celebrity and this led to her having enemies that included most prominently singer Frank Sinatra. When she ridiculed him for the “bimbos” and “has-been” girlfriends he paraded around with, he responded by calling her “the chinless wonder,” making fun of her appearance. He also sent a fake tombstone to her office.

How influential was she as a reporter?

There is not a media personality today who can match the journalistic career that Dorothy enjoyed for nearly three decades. Besides being nominated for a Pulitzer Prize, she was arguably the most trusted reporter in the world which permitted her the best sources for her stories. This led to an astounding number of “scoops,” including being the first reporter who expose JFK’s affair with Marilyn Monroe and later, being the only reporter to interview Jack Ruby at his trial and then expose his Warren Commission testimony before it was to be released. During her era, people got most of their news from newspapers and she was, as the New York Post proclaimed, “The most powerful female voice in America.”

What stance did Dorothy Kilgallen take on the JFK assassination? And how might that have been connected with her death?

Dorothy launched an 18-month investigation of the JFK and Oswald assassinations and without doubt, it is the most extensive investigation of those events in history. She was there when it all happened and at the Ruby trial so she is a true eyewitness to history. In the fall of 1965, she was about to include her belief that the assassinations were simply “Mafia hits” start to finish based on motive, that New Orleans Don Carlos Marcello had masterminded the assassinations based on revenge against the Kennedy’s. As November arrived, she was getting ready to complete a book for Random House exposing the truth and those threatened by it could not let her live.

John F. Kennedy. By White House Press Office (WHPO) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

Do you think she was murdered?

The official cause of death, accidental due to a combination of an overdose of barbiturates and alcohol is flawed based on the primary evidence presented in the book. She certainly did not commit suicide and that leaves murder as the logical choice as to how she died. This said, since this book is true crime murder mystery, readers should make up their own minds based on the book content and watching the more than 50 videotaped interviews with those who knew her best at www.thedorothykilgallenstory.org.

Did her JFK assassination research file disappear with her death?

Yes, this is one of the many mysteries connected to Dorothy’s death that readers around the world have debated through the more than 175 Amazon reviews and emails I have received from both the US and countries such as Japan, Australia, and even Iceland. I’m pleased to say the book is in its 6th printing with a film in development in LA that will focus on Dorothy’s life and times, and her death.

Wow! Congratulations. I want to see the film when it comes out.

Mark Shaw, with permission.

Was the file ever found again?

No, but I believe it still may be out there somewhere and recently fresh evidence has been forwarded to me by a person close to Dorothy’s family as to the possible whereabouts of the file. We are following up on that information.

How would Kilgallen’s murderer have known where to look for the file? Didn’t she die on a different floor of the house than the floor where she kept her file?

Dorothy never made a secret of her intention to expose the truth about the JFK and Oswald assassinations and this contributed to her death. It was common knowledge that she always kept the file close to her and shared it with no one but as November 1965 neared, she told her hairdresser Marc Sinclaire that she was “afraid for her life and for her family,” and a second hairdresser Charles Simpson that “if the wrong people knew what I know about the JFK assassination, it would cost me my life.” They did know, and it did cost her her life.

If I were in Dorothy Kilgallen’s shoes, I wouldn’t have left my file around the house without having made copies for protection. I’d have put one copy in a safe deposit box, for instance, and given another copy to my attorney with instructions what to do with it in the case of my untimely demise. Is there any indication that she took those precautions? She took a trip to Switzerland before her death and at least one acquaintance thought she had a safe deposit box there. Has anyone checked to see if a Swiss safe deposit box might hold a copy of the file?

You have to remember that there were no copy machines back then and so it would have been a carbon copy that might have been in existence. This said, there is no credible evidence that any copy of the file existed. There is also no credible evidence that she took any copy to Switzerland or gave a copy to anyone.

NEW YORK, NY – 1960s: (L-R) The panel of judges along with the host of What’s My Line? Arlene Francis, John Charles Daly, Dorothy Kilgallen (right), and Bennett Cerf pose for a portrait circa 1960’s in New York, New York. (Photo by Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images), courtesy of Mark Shaw.

Tell us about the new investigation into Dorothy Kilgallen’s death.

After I requested that NYC District Attorney Cyrus Vance, Jr. investigate Dorothy’s death (not re-investigate since there was no investigation in 1965 despite a staged death scene and other evidence pointing to a homicide), the NY Post reported that the DA had opened an investigation into her death 52 years later. I have subsequently been working with the DA’s office by forwarding fresh evidence that will assist with the investigation but I’d like to see the investigation proceed more quickly than it has since as the victim of a homicide, Dorothy has rights and I am fighting to make sure she gets the justice she deserves that was denied her so many years ago.

Thank you, Mark Shaw!

Do you think a new investigation is warranted, 51 years later? Please comment below.

More books by Mark Shaw

Mr Shaw has also written The Poison Patriarch, Miscarriage of Justice, Beneath the Mask of Holiness, Melvin Belli: King of the Courtroom, Stations Along the Way, and Down for the Count. He has penned articles for The New York Daily News, USA Today, Huffington Post and the Aspen Daily News, which he co-founded. More about Mr. Shaw, who lives in the San Francisco area, may be learned at markshawbooks.com and Wikipedia (Mark William Shaw).

Literature on point:

Susan Edelman, “Manhattan DA’s Office probing death of a reporter with possible JFK ties,” New York Post (Jan. 29, 2017).

Mark Shaw, The Reporter Who Knew Too Much: The Mysterious Death of What’s My Line TV Star and Media Icon Dorothy Kilgallen (Post Hill Press, 2016).

The post Dorothy Kilgallen: Crime Reporter as a Murder Victim? appeared first on Ann Marie Ackermann's author website.

April 26, 2017

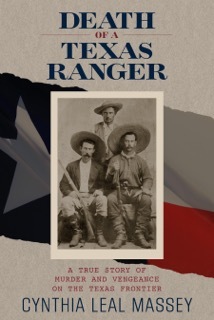

Death of a Texas Ranger: Interview with Author Cynthia Leal Massey

Real quick now: What are the first things that come to your mind when you think of the Texas frontier?

Cowboys? Check.

Rangers? Check.

Indians? Check.

Mexicans? Check.

But how about paleontologists? Did you think about them, too?

Fossil hunters tended to stick to the background, picking their way through the Texas bone beds, but they were very much part of the frontier. Texas was a magnet for 19th-century collectors. Universities and museums on the east coast, even in Europe, hired them to augment their collections. Mix the paleontologists up with the usual cast of characters and you sometimes had a great recipe for violence and murder.

In her book, Death of a Texas Ranger (2014), Cynthia Leal Massey successfully stirs a paleontologist into the frontier murder recipe. Her book deals with what was once the coldest case on the San Antonio court docket (37 years to case closure!) and features all the traditional characters listed above. The culinary result was a winner. Death of a Texas Ranger took the 2015 Will Rogers Silver Medallion Award for Best Western Nonfiction and the 2015 San Antonio Conservation Society Publication Award.

Cynthia Leal Massey joins us for an interview today. Welcome, Cynthia!

Courtesy of Cynthia Leal Massey.

Death of a Texas Ranger actually chronicles two homicides, one of a Ranger in 1873 and another of a postmaster in 1878. Tell us first how the Ranger died.

On the morning of July 9, 1873, Minute Men Texas Ranger Troop V of Medina County was breaking camp at a site in northwest Bexar County, Texas, near the settlement of Helotes, getting ready for a scout. Private Cesario Menchaca came out of the bushes and confronted Sgt. John Green (a German immigrant originally born Johann Gruen). After a few tense words, Sgt. Green moved toward Menchaca, who had a rifle in his hands, and Menchaca shot him, killing him on the spot.

John Green’s company was a colorful mixture of Texans, Germans, and Mexicans. Did Germans and Mexicans often serve as Rangers?

During the early days of the Ranger companies, Mexicans did serve in a sort of multicultural unit; however, it was not the norm. The Ranger company that John Green served in was composed of ranchers and farmers from northwest Bexar County and southeast Medina County. A mixture of Germans, Mexicans (or Texicans), and Anglos, lived in this region. These men had something in common–they wanted to protect their families and their livestock.

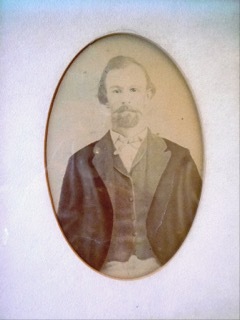

John Green, ca. 1869. Courtesy of Shirley Sweet.

Menchaca fled to Mexico. The U.S. and Mexico already had an extradition treaty at the time of the killing. Why didn’t it help Texas extradite Cesario Menchaca from Mexico?

Apparently, no one was able do the work necessary to get the extradition paperwork together.

How did the Green homicide end up becoming the coldest case on the San Antonio court docket?

The United States has no statute of limitations on murder. The 1873 indictment charge was murder, so by necessity, it moved forward on the docket, despite no activity in his apprehension. In 1897, Deputy Will Green, the victim’s son, petitioned the court for a new Bill of Indictment, since the sitting judge was eager to remove old cases from the docket. Deputy Green was successful and with a new bill of indictment and case number, the murder case remained on the docket. However, because of circumstances regarding the outcome of the extradition request, the case remained on the docket until Menchaca’s death in 1910, 37 years from the initial indictment.

A fossil of the extinct turtle Baena arenosa from the Green River Formation, Wyoming, USA estimated to be fifty million years old. Professor Leidy also collected fossils of this species. By (c) Linnas, Shutterstock.com, with permission.

How did a turtle fossil lead to a fossil hunter killing the postmaster?

Gabriel Wilson Marnoch, a frontier naturalist, lived in Helotes. He was a neighbor of the Green family and was allegedly involved in the Green killing. Marnoch collected specimens and fossils and mailed large boxes of his finds to scientific institutions around the country. He was a frequent visitor to the Helotes Post Office, where Carl “Charles” Mueller was postmaster. In the spring of 1877, Marnoch received correspondence from Professor Joseph Leidy of the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, indicating that one of Marnoch’s packages to him, which contained “turtle remains,” had arrived in a state of “ruins.” Marnoch confronted the postmaster about the mishandled package, demanding recompense, which elicited bad feelings on both sides. This ignited what came later.

In Death of a Texas Ranger, you write that post-Civil War Texas was a magnet for paleontologists. Why?

The mid-nineteenth century is often referred to as the Age of Darwin, a nod to British naturalist Charles Darwin, who in 1859 and 1871, respectively, published his seminal scientific works, The Origin of Species and The Descent of Man. Texas was still very much a frontier, with virgin landscape, and those interested in the natural sciences descended upon Texas in troves. According to Samuel Wood Geiser, author of Naturalists of the Frontier, “several hundred men of science labored in Texas in the pioneer days.” Marnoch’s father, Dr. George Frederick Marnoch, a graduate of the Royal College of Surgeons in Edinburgh and the University of Edinburgh, was a contemporary of Charles Darwin and likely shared a medical class with him. Gabriel mentioned this many years later, saying that he’d had “considerable correspondence” with Darwin and fellow naturalist Thomas Huxley, although said letters have yet to surface.

Gabriel Marnoch and his wife Carmel Trevino (ca. 1919). Courtesy of Cynthia Leal Massey from her book, Helotes, Where the Texas Hill Country Begins.

Gabriel Marnoch collected for Professor Edward Drinker Cope at the Haverford College in Pennsylvania. Cope’s feud with paleontology Professor Othniel Marsh of Yale is now the stuff of legend. Can you tell us about their clashes?

There are several good books about the feud between Cope and Marsh. In a nutshell, the paleontologists were involved in something now called “The Bone Wars.” This was a period of intense fossil hunting and discovery in the mid-nineteenth century. Trying to outcompete each other, they resorted to spying, counter-spying, bribery, theft and even destruction of bones to remain “on top.” Marsh’s charges of errors, distortion, and fraud against Cope and the professor’s countercharges were published in the spring and summer of 1873, in The American Naturalist, which Cope finally purchased in 1877 to stop further allegations from being published.

Cliff Chirping Frog, Marnoch’s great scientific discovery. By Dawson at English Wikipedia (Transferred from en.wikipedia to Commons,) CC BY-SA 2.5, via Wikimedia Commons.

How did Marnoch help cement Cope’s reputation?

Marnoch hosted Cope in Helotes and other Texas environs on a two-week quest for new fossils in the fall of 1877. After that, Marnoch, whom Cope hired as a field correspondent, began sending specimens to the paleontologist. Marnoch discovered several new specimens, one a frog that Professor Cope said was “a new genus of Cystignathididoe.” Cope gave the cliff chirping frog the scientific name Eleutherodactylus (Syrrhophus) marnockii, in honor of his field correspondent. A few other Marnoch discoveries named by Cope: the Texas Banded Gecko, Short-Lined Skink, and the Barking Frog.

Why were the murder charges against Marnoch dismissed?

Marnoch killed the postmaster in March 1878. He was indicted for murder on April 4, 1878. In November of that year, the jury could not agree on a verdict and a mistrial was declared. At his second trial May 17, 1879, the jury convicted him of murder in the second degree and sentenced him to confinement in the penitentiary for twenty years. His attorneys kept him out of prison while they appealed his murder conviction and the appeals court remanded his case back to the district court for a new trial. The judge believed that the jurors weren’t given appropriate directions regarding self-defense. His lawyers were able to get continuances due to their inability to recall several important witnesses who’d moved out of the country. The murder case was finally dismissed in 1887.

How did John Green’s son try to reopen his father’s case decades later?

In 1897, Deputy Will Green learned that the 37th District Court of Bexar County was reviewing old cases on the docket and that caused him to seek a new indictment. The original indictment for murder against Cesario Menchaca was filed in October 1873. Deputy Green was able to assemble several of his father’s old Ranger comrades before a new Grand Jury, and was successful at obtaining a new indictment on May 26, 1897. This enabled him to seek and obtain an extradition requisition from the Governor of Texas.

Death of a Texas Ranger. Courtesy of Cynthia Leal Massey.

Thanks, Cynthia!

A fascinating twist at the end of the book concerns a discovery about the paleontologist. He may be had more to do with the death of a Texas Ranger than Will Green originally thought. But I won’t spoil the ending for you – you need to read the book yourself.

Cynthia Leal Massey is working on a screenplay adaptation of Death of a Texas Ranger, and with luck, we might get to see it out the big screen. Fossils and felonies should make a great mix. I’ll be there if the film comes out. If you go too, grab an extra large bag of popcorn and come sit with me.

Literature on point:

Cynthia Leal Massey, Death of a Texas Ranger: A True Story of Murder and Vengeance on the Texas Frontier (Guilford, Connecticut: TwoDot, 2014).

Charles H. Sternberg, The Life of a Fossil Hunter (1st ed. Henry Holt & Co., 1909, reprint, Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1990) [Another account of a 19th-century paleontologist collecting for Cope, in part in Texas; considered a classic among paleontologists].

The post Death of a Texas Ranger: Interview with Author Cynthia Leal Massey appeared first on Ann Marie Ackermann's author website.

April 18, 2017

Mary Todd Lincoln’s Castle Ghost in Germany

Mary Todd Lincoln, 1860-1865. Brady-Handy Photograph Collection (Library of Congress). Public domain.

Germany as a haven after the Lincoln assassination

One of the lesser known aspects of the Lincoln assassination is the aftermath that played out in Germany. All the surviving occupants of the presidential box at Ford’s theater ended up moving to Germany. Mary Todd Lincoln and her son Tad lived in Frankfurt from 1868 to 1870, and Henry Rathbone moved to Hanover with his wife Clara and children in 1882 when the president appointed him U.S. Consul there. [Rathbone then became involved in a true crime himself. He murdered his wife a year later in Hanover – but that will be the subject of another post.]

I enjoy following the Lincoln and Rathbone sojourns in Germany because I live here, speak the language, and can research them. And that’s why a letter from Mary Todd Lincoln about a castle ghost caught my eye. There’s a possible mistake in there that’s leaked out into the biographical literature and I hope to point it out with this post.

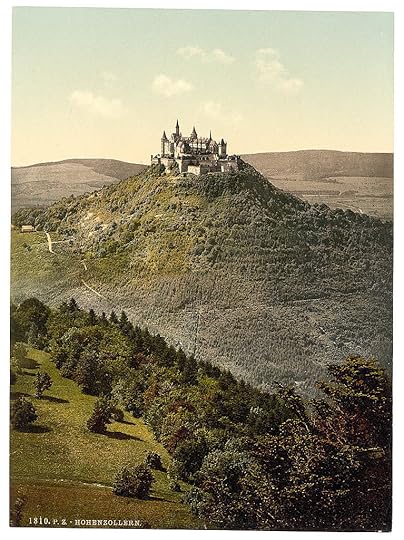

Hollenzollern castle on a 19th-century postcard. Was this the haunt of Mary Todd Lincoln’s castle ghost? Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, public domain.

Mary Todd Lincoln in Germany

Mary stayed at the Hotel d’Angleterre in Frankfurt while Tad attended boarding school nearby. By February, Frankfurt had gotten too cold for her and she decided to travel to the Mediterranean. Along the way, she stopped at the spa town of Baden-Baden in the Rhine Valley. Once she reached Nice, France, Mary penned a letter to her friend Eliza Slataper, a member of the Lee family in Virginia:

En route to Nice, I stopped for a day or two at Baden to see a lady from America, who resides most of the time in Europe. We visited a castle near Baden, where the veritable “White Lady,” is said, delights most to dwell, and where Napoleon signed his memorable treaty, in roaming the immense building, I said to our two attendants “have you ever seen her” – to which, of course, they both replied – “We often do.” As you know, Germans are very superstitious, and from the King of Prussia, down to his humblest subject, believe in her frequent appearance.*

“The white lady appearing to King Frederick I in 1713 shortly before His death.” Lithography by Ludwig Löffler, 1851 [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

Mystery of Mary Todd Lincoln’s castle ghost

Who or what was Mary Lincoln’s castle ghost? And where was the castle the white lady haunted? The answer is elusive.

One biography identifies the castle as the Hohenzollern castle in the Province of Hohenzollern. The royal family of Hohenzollern fits nicely to the white lady story. Kunigunde von Orlmünde, a widowed mother, she was engaged to marry another member of the Hohenzollern family, but thought her children came between herself and her fiancé. So she stabbed her children’s skulls with a needle and killed them. Later she sought repentance in Rome and entered a convent, where she died in 1351. According to legend, her ghost appeared throughout history to various members of the Hohenzollern family before they died, including the King of Prussia. Thus, Mary’s mention of the king in her letter appears to be a reference to the white lady of the Hollenzollern dynasty.

But the Hohenzollern castle as the dwelling for Mary Todd Lincoln’s castle ghost presents some problems. Several Prussian castles, including Berlin, Kulmbach, Rudolstadt, and Bayreuth, belong to the white lady’s traditional haunts, but I can’t find a reference to her ever spooking the Hohenzollern castle itself.

The Hohenzollern castle as it appears today. Pixabay.

Problem of distances

There’s yet another reason why Hohenzollern can’t be the home of Mary Todd Lincoln’s castle ghost. It’s too far away. Baden-Baden lies on the west side of the Black Forest. To travel from Baden-Baden, Mary would have had to cross or skirt the Black Forest mountain range from the Grand Duchy of Baden into the Kingdom of Wurttemberg, and from there cross the Neckar Valley to the east and travel up into the Prussian Province of Hohenzollern on the Swabian Alb plateau. That was 44 miles as the crow flies, but at least 68 miles on the road, and three different countries.

Mary and her friend couldn’t have saved time by travelling by train, either. The Zollenalb train line connecting Tübingen to Hechingen (the nearest town to the castle) didn’t open until June 29, 1869, several months later. The women would have had to have completed at least part of the trip by horse and carriage. The journey, then, would have been too long to fit in as a side trip during a one to two day visit to Baden-Baden.

Napoleonic treaty riddle

Mary’s other clue, that Napoleon signed a treaty at the castle, doesn’t help either. Napoleon, as far as I can determine, never signed a treaty at the Hohenzollern castle nor at any other castle in southwestern Germany. Mary might have been confused on that point. Please correct me if I’m wrong and leave a comment if you know what Mary might mean by Napoleon’s castle treaty.

The Hohenbaden castle offers a better location for Mary Todd Lincoln’s castle ghost. Pixabay.

Hohenbaden castle and the gray lady

A prime location for Mary Todd Lincoln’s castle ghost would have been the Hohenbaden castle right next to Baden-Baden – one of the city’s major tourist attractions – and a very manageable side trip from town. The Hohenbaden castle doesn’t have a white lady, though. It has a gray one. And her story would have been far more intriguing to Mary Todd Lincoln.

The margravine who lived in the castle became the gray lady after her death was a different kind of a mother than the white lady of the Hollenzollerns. By all accounts, she loved her baby son more than anything in the world. One evening, she wanted to show him his inheritance. She took him up a high tower and held him out over the balustrade to show him all the villages, fields, and farms over which he would one day rule. But he slipped out of her hands and tumbled down the castle walls and cliffs. Panicked, the margravine rushed down all the castle steps to search the ground below the cliffs. Although she had all her servants and maids help her, she never found her little boy’s body again. The margravine died in grief. Now, according to the Baden-Württemberg’s official website for its castles and gardens, she haunts the castle. You can still hear the margravine wailing as the wind whips the crevices in the cliffs, and at midnight, her gray-clad apparition drifts from room to room, her long white hair waving about her face.

Mary, who herself had two sons slip through her fingers into eternity, would have related much more to the mourning gray lady than the murderous white one. Might her memories of Edward and Willie have prompted her questions to her tour guides?

Gray lady in folklore

Although gray lady ghosts aren’t as common as the white ones, they do pop up in 19th-century literature. The gray lady of Caputh is another example. By 1846, a poem about the gray lady of Hohenbaden appeared in a collection of Baden legends. To give you a taste, I’ve translated the first four lines:

Habt ihr gehört von der grauen Frau

Im Bergschloß Hohenbaden?

Bethört von finstrer Macht, dem Gau

War sie zu Schreck und Schaden.**

Have you heard of the lady gray

In Hohenbaden’s cliffside palace?

Bewitched by darkness, she steals away

To spew her fright and malice.

The poem underscores the fame of the gray lady by the time Mary visited Baden-Baden in 1869. Today, the castle’s website describes the gray lady as the most famous of the castle’s legends. The ghost could have easily become a subject of the castle tours by the time Mary visited in 1869.

Did Mary Todd Lincoln walk these grounds? Hohenbaden castle by (c) Yakovlev Sergey, Shutterstock.com, with permission.

Hohenbaden as the better choice

It’s possible that Mary got the color of the ghosts mixed up by the time she reached Nice and wrote her letter. Even the names of the castles are quite similar, Hohenzollern and Hohenbaden. That might have confused her in any conversations or reading on the topic.

Nevertheless, the Hohenbaden castle, for its proximity to Baden-Baden and a ghost story that matches Mary’s letter, offers a far better alternative than Hohenzollern for Mary’s side trip destination and the haunt of Mary Todd Lincoln’s castle ghost.

The question of where she thought Napoleon signed his “memorable treaty” remains open and offers a way to solve the riddle of Mary’s destination. My cursory survey of the treaties Napoleon I and III signed didn’t turn up anything in a southwestern German castle. Knowledge, however, is a cumulative and cooperative effort, and perhaps a reader knows more about the topic than I do. Please leave a comment if you can contribute. In doing so, you’ll also augment Mary Todd Lincoln’s biography.

You might also enjoy reading about Mark Twain’s visit to Baden-Baden several years later and his encounter with the Prussian empress.

Literature on point:

Baden-Württemberg, Städtliche Schlösser und Gärten, “Ein Geist im alten Schloss: Die graue Frau,” Altes Schloss Hohenbaden.

Betty Boles Ellison, The True Mary Todd Lincoln: A Biography (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2014).

Jan von Flocken, “Die weiße Frau – ein Gespenst macht Geschichte,” Welt (Oct. 7, 2007).

**Ignaz Hub, “Die Graue Frau von Hohenbaden,” in Badisches Sagen-Buch II, August Schnezler, ed. (Karlsruhe: Creuzbacher & Kasper, 1846), 180-184.

*Mary Todd Lincoln to Eliza Slataper, Feb. 17, 1869 (in Turner, 26-27).

Literarisches Colloquium Berlin, “Die graue Frau,” Literatur Port (2015) [gray lady of Caputh].

Justin G. Turner, “The Mary Lincoln Letters to Mrs. Felician Slataper,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society 49(1):7-33 (Spring 1956).

The post Mary Todd Lincoln’s Castle Ghost in Germany appeared first on Ann Marie Ackermann's author website.

April 11, 2017

Interview with Author Hank Garfield, Descendant of President James Garfield

President James Garfield. Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division, public domain.

The lives of our forefathers send ripples through the generations, shaping who we are today. If one of those forefathers happened to be a U.S. President, he shaped both national and familial history. And if that forefather was assassinated in office, his surviving family carried an extra burden of grief and shock.

Four U.S. Presidents were assassinated: Abraham Lincoln, James Garfield, William McKinley, and John F. Kennedy. Of those, only two – James Garfield and John F. Kennedy – have living descendants today. Hank Garfield, a descendant of President Garfield, joins us today to talk about his forefather, family legacy, and life today.

Charles Guiteau, a disappointed office-seeker, shot and injured President Garfield at a Washington, D.C. train station on July 2, 1881. He died several weeks later, on September 19, as a result of his injuries. In a previous blog post, I interviewed author Fred Rosen, an author of a new book about the Garfield assassination. Rosen claims Garfield’s physician, Dr. Bliss, deliberately killed Garfield, committing second-degree murder, and that Alexander Graham Bell preserved the clues. Hank Garfield wrote the foreword to Rosen’s book.

Hank Garfield with the Washington, D.C. memorial to President Garfield in the background. Courtesy of Hank Garfield.

Hank, you are a descendant of President Garfield. Just how are you related to him?

I’m the great-great-grandson of the president. He had four sons, and they all had sons, and so forth, so there are a lot of Garfields running loose in the USA.

Did the assassination still affect your family several generations later? If so, how?

I don’t know that the assassination affected my family at all within my lifetime. It’s an interesting conversation starter, but it also leaves people with the misguided impression that we have Kennedy-esque connections and wealth, which we don’t.

You actually got to meet one of the Kennedys at school. What was that like? Did you ever talk about either family’s history?

That would be Michael Kennedy, RFK’s son. We were in the same class at St. Paul’s in Concord, New Hampshire. He was small, athletic, charming, and much more worldly than I was. Our circles of friends overlapped a little. We played backgammon and had a conversation that went along the lines of “You’ve got the Garfield chin, and I’ve got the Kennedy nose.” We both liked the TV show Kolchak: The Night Stalker. Some Secret Service agents came to school and followed him around for a couple of weeks when there was a threat against the family. He was killed in a skiing accident when he was about forty. I remember seeing it on the news in California.

Note: The Kennedy Hank Garfield means was Michael LeMoyne Kennedy (1958-1997). He died went he hit a tree while playing football on skis on December 31, 1997 in Aspen, Colorado.

Did your family have any stories or memorabilia about President Garfield?

I honestly can’t remember any. I have a silver cup that Lucretia Garfield (the President’s widow) gave to my grandfather in 1903, when he was a boy. Their names are inscribed on it. I’m not sure how it came to be in my possession.

You are an author. What kind of books do you write?

I’ve published five novels under the name Henry Garfield but am now writing as Hank Garfield. I’m shopping a long novel called A Sprauling Family Saga, which is what it is, and I also write baseball science fiction.

Tartabull’s Throw, one of Hank Garfield’s novels. Courtesy of Hank Garfield.

Does your family history have an influence on your writing?

I guess I like to write with large ensemble casts; perhaps growing up with a large extended family had something to do with that.

In your foreword for Fred Rosen’s book, you state that President Garfield was one of the few scholars to occupy the White House. On what do you base that?

There’s a persistent legend that he could write Greek with one hand and Latin with the other. I’m not sure I believe this. But his mother put great stock in education, believing it was the way for him to escape the poverty of living in a fatherless household on the Ohio frontier (His father died when he was very young). He is also credited with an original proof of the Pythagorean theorem. He seems to have had a curious mind that moved in many directions. Most true scholars exhibit this kind of interest in a broad range of subjects. They used to be called Renaissance men, an allusion to Da Vinci, I guess.

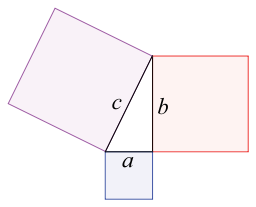

Pythagorean theorem: a2 + b2 = c2. Did you know that President Garfield came up with a new proof? By en:User:Wapcaplet [GFDL or CC-BY-SA-3.0], via Wikimedia Commons.

Might the Garfield legacy have inspired you to write?

I grew up in a household full of books. A couple of them were about my great-great grandfather. His son Harry (my great-grandfather) became president of Williams College, the President’s alma mater. My parents were teachers and readers. In the summer we lived without TV. I was always encouraged to read. That, above everything else, inspired me to write.

What do you do now?

I write novels and teach creative writing at the University of Maine. Lately I’ve been working in the genre of baseball science fiction. I also write a weekly blog called Slower Traffic (slowertraffic.net) about living without a car in a rural state. I haven’t owned a car in ten years. It’s the only New Year’s resolution I’ve ever kept.

John Cabot in traditional Venetian garb by Giustino Menescardi (1762). A mural painting in the ‘Sala dello Scudo’ in the Palazzo Ducale. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

One of your books, The Lost Voyage of John Cabot, is a historical novel. What inspired you to write about the Age of Exploration?

Well, I love books, and I love boats. My father had a small schooner. I don’t remember not knowing my way around a small sailboat. Today I own a 25-foot sloop and a couple of dinghies. I’m fascinated by the lasting legacy of that time: why the Brazilians speak Portuguese and the Quebeckers speak French, but some Portuguese words creep into Canadian French because of the interactions between New World explorers. In 1983 I was working for a game company in California, and we were looking for mysteries in different genres that we could make into game scripts. John Cabot disappeared on his second voyage to America. I wrote a script in which the player sets out to search for him. The company went under before it could be produced, but it was a great starting point for a book.

Note: John Cabot (c. 1450-1500) was a Venetian explorer who sailed to mainland North American in 1497. Historians consider him to be the first European to visit the North American mainland since the Norse settlement of Vinland.

Do any of your other books touch on crime?

My first novel, Moondog, is a classic whodunit, in which a Holmes and Watson team lead the reader on a search for a murderer. Only the murderer is a werewolf. But the structure is basic: a series of murders that the reader is invited to solve along with the protagonist. From a review by Gahan Wilson, the New Yorker cartoonist: “[Moondog] moves along in the classic pattern and follows the rules; the twist Garfield’s given to it is to have the action take place in convincing Steinbeck country amidst Steinbeckian folk, all of whom are quite well-realized and true to the master’s leanings.” Obviously I was flattered by the comparison, as I was by the mention of Carl Hiaasen in a review of the sequel, Room 13. They are two of my favorite writers.

Thanks, Hank Garfield, for joining us!

The post Interview with Author Hank Garfield, Descendant of President James Garfield appeared first on Ann Marie Ackermann's author website.

April 5, 2017

The Royal Origin of the Police Lineup: How a Queen’s Funeral Changed Criminal History

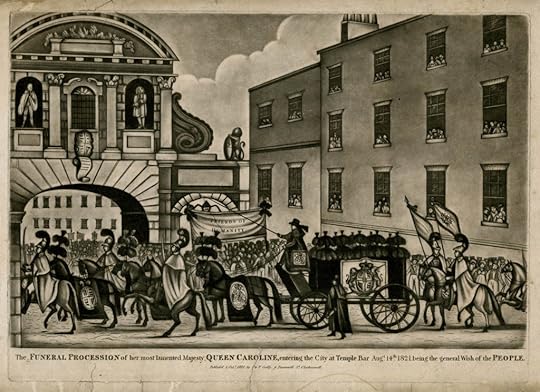

The Funeral Procession of her most lamented Majesty Queen Caroline (1821 Mezzotint with etching), ©Trustees of the British Museum, with permission.

A royal funeral makes criminal history

Black plumes bounced on the horses’ heads as they pulled the hearse through the rain and mud. The muffled hoofbeats foreshadowed change. Neither horse nor guard nor mourner could know the path before them led into criminal history, but it did. The reaction to Queen Caroline’s funeral procession became the origin of the police lineup.

Thirteen mourning carriages and the Life Guards, who had orders to escort the queen’s body, accompanied the hearse. Their route deviated from the normal royal funeral: Instead of going into the city center, the procession was to skirt the center and go around it. Ever since Caroline of Bruswick’s death a week ago, on August 7, 1821, officials feared the public would riot at her funeral procession.

And they were right.

But what they couldn’t foresee was how the procession would lead to an innovation in criminal procedure. Just one week later, London would stage an event that became the origin of the police lineup – with the Life Guards as suspects.

A police lineup. By Oslo police (Torgersen-sa) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

Lineups and showups

Police lineups – or identification parades, as they are known in the UK – have long been part of law enforcement’s tool kit for identifying suspects. But the origin of the police lineup is a bit murky.

The Baltimore Police Department has been using lineups for over sixty years. They’ve been part of British criminal procedure for much longer. An 1874 memorandum to the Home Office claimed the Metropolitan Police had used them since its inception. The earliest known police order for the regular use of the lineup was in 1860. Several court cases document lineups outside of London already in the 1850s.

Law enforcement developed lineups in response to criticism about the lineup’s older cousin, the showup. In a showup, the police apprehend a suspect matching a witness’s description, typically not long after taking the initial police report. The police bring the suspect back to the witness for an eyewitness identification: Was this person the perpetrator or not?

False identifications

Showups, however, can lead to false identifications. The problem is suggestiveness. Because the police are showing only one suspect, witnesses might have tendency to pick that one out.

Misidentifications weren’t just a modern concern. Even in the 19th century, scholars discussed the danger. William Wills listed several cases on misidentification in his 1838 essay on circumstantial evidence.

Caroline of Brunswick, queen consort to King George IV.Thomas Lawrence [1804, Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons. Events following her funeral procession became of origin of the police lineup.

Origin of the police lineup

When the British police first started regular lineups, they might have been thinking of the example of the Life Guards at Queen Caroline’s funeral. Caroline had a controversial career as queen consort, yet remained very popular with the people. The city folk, angry that her funeral procession wasn’t supposed to head downtown, decided to force it. People set up barricades along the route to detour the procession where they wanted it to go.

When the Life Guards encountered a set of barricades, a riot broke out. The crowd pelted the guards with rocks and injured several of the troops. With orders to use their weapons to disperse the rioters, the guards shot and slashed a path through the people. Two men in the crowd were killed.

One week later, on August 21, 1821, witnesses gathered at the barracks to identify which guards had been shooting. The regiment lined up in formation. Under the supervision of the Bow Street magistrates (an early police force), the witnesses walked through the troops’ ranks to study their faces. Their identifications and testimony were recorded in the inquest proceedings.

Edward Higgs calls the inquest proceedings at the Life Guard barracks one of the first recorded instances of an identification parade. In the UK at least, Queen Caroline’s funeral procession case played an important role in the origin of the police lineup.

But the idea of the lineup was much older. It may have come from France, and interestingly, that case also had a royal connection.

The Life Guards today. By PRA (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 or GFDL], via Wikimedia Commons

A controversial French showup

One of the greatest criminal scandals in the reign of Louis XIV was a vast network of poisoners. Between 1679 and 1680, French police arrested over 400 suspects for crimes related to poisoning and black magic. Witnesses alleged that the web of conspirators reached all the way to the king’s court – with the king himself, in once instance, as the intended victim.

Claude de Vin des Oeillets, the king’s former lover and once a member of his court, found herself facing accusations. And she thought she had a brilliant way of proving herself innocent. Her accusers were jailed in the dungeon of Vincennes. Why not take me there, she asked her interrogator, and show me to them? Oeillets swore none of her accusers would even recognize her.

Her plan backfired.

Investigators brought her down to a room near the dungeon and had the guards bring the witnesses in. Two identified her immediately.

Claude de Vin des Oeillets (Mademoiselle des Oeillets, 1637-1687), mistress of Louis XIV of France. Pierre Mignard, public domain. She may have inspired the first argument for a police lineup.

Argument for the world’s first police lineup

Oiellets’s showup procedure reaped criticism. One of Louis’s ministers, Jean Baptiste Colbert, attacked the showup as prejudicial. Because she was the only person presented to the witnesses, Colbert said, it would have been too easy for the witnesses to guess who Oeillets was. Colbert said they should have shown her with four or five other people.

That is quite a modern argument! What Colbert was actually demanding was the world’s first police lineup.

So if France is not the birthplace of the lineup itself, it still might be the origin of the police lineup with respect to its philosophical underpinnings. And that’s fitting, because France also gave birth to the true crime genre.

Literature on point

John Adolphus, The Last Days, Death, Funeral Obsequies, &c of Her Late Majesty Caroline (London: Jones & Co., 1822).

Frederick H. Bealefeld, “Research and Reality: Better Understanding the Debate between Sequential and Simultaneous Photo Arrays,” University of Baltimore Law Review 42(3):513-534, 519 (2013).

David Bentley, English Criminal Justice in the 19th Century (London: Hambledon Press, 1998).

Rt. Hon. Lord Devlin (1976). Report to the Secretary of State fort he Home Department of the Departmental Committee on Evidence of Identification in Criminal Cases. HMSO.

Edward Higgs, Identifying the English: A History of Personal Identification 1500 to the Present (London: Continuum, 2011).

Holly Tucker, City of Light, City of Poison: Murder, Magic, and the First POlice Chief of Paris (New York: W.W. Norton, 2017).

William Wills, An Essay on the Rationale of Circumstantial Evidence (London: Longman, Orme, Brown, Green, and Longmans; 1838).

The post The Royal Origin of the Police Lineup: How a Queen’s Funeral Changed Criminal History appeared first on Ann Marie Ackermann's author website.

March 28, 2017

Dr. Gudden’s Death Mask as a New Clue in the Death of Bavaria’s King Ludwig II

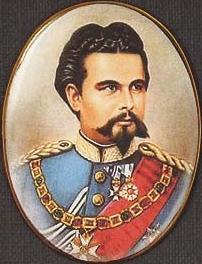

Ludwig II portrait by Carl Theodor von Piloty, public domain

Hot evidence in a cold case

New evidence in a 130-year-old unexplained death? It’s unusual, but it can happen.

In the case of the mysterious death of Bavaria’s King Ludwig II, the new evidence takes the form of Dr. Gudden’s death mask. Munich’s Rosenheim Museum rediscovered it in its attic in 1999. The mask tells a story that casts new light on Ludwig’s death.

Bavaria’s greatest unsolved mystery

Just how did King Ludwig II die on 13 June 1886? No one knows for sure.

The Bavarian government had just deposed the 40-year-old king as unfit to rule and placed him under guard at Bavaria’s Castle Berg on the shores of Lake Starnberg. Following an evening walk on the lakeshore, Ludwig and Dr. Bernhard von Gudden, Bavaria’s best-known psychiatry professor and expert witness in the proceedings to depose the king, were found floating face-down in the waist-deep waters of the lake. No one witnessed their deaths; no one knew exactly what happened.

Autopsy results on the king found no cause of death. There was no water in his lungs and no visible mortal injury – just a scrape on his knee. Theories about the deaths have spiraled out to suicide, homicide, and various forms of an accident. You can read more about the mysterious case here, and for the reasons many Bavarians think it was murder, click here.

The Bavarian government’s official explanation

The Bavarian government’s official explanation for the deaths was homicide-suicide. King Ludwig II rushed into the lake to commit suicide. When Dr. Guddden tried to stop him, Ludwig killed him. Then he waded out into deeper waters to drown himself.

The problem with this theory is that two pieces of evidence – the men’s pocket watches and Dr. Gudden’s death mask – bear silent witness to the contrary.

The pocket watch discrepancy is controversial. Image from Pixabay.

The riddle of the pocket watches

King Ludwig’s pocket watch stopped at 6:54 pm. If the government’s theory were true, you’d expect Dr. Gudden’s watch to have stopped earlier because he would have been floating in the water longer than King Ludwig II.

The reverse, however, is true. Dr. Gudden’s watch stopped at 8:06 pm – 72 minutes after the king’s watch did. This discrepancy is one of the most hotly debated aspects of the case.

Once water enters a pocket watch’s machinery, it will stop very quickly. In a televised experiment for a German documentary, a watchmaker dropped a replica of a 19th-century pocket watch into a glass of water. It stopped after 20 seconds.

Various theories have been advanced to explain why the discrepancy might still be consistent with the government version. According to one, Dr. Gudden often forgot to wind his watch. Hence, it may have been running too fast or slow. Likewise, historians have argued the king habitually set his watch back a half hour or more.

The doctor was known to close his watch lid very tightly, and that might have affected how quickly water entered the watch’s gears. Furthermore, Ludwig wore less clothing – only a shirt and vest – when he entered Lake Starnberg. He had stripped off his jacket and greatcoat first, but Dr. Gudden kept on his. Thus, it would have taken the water longer to saturate Dr. Gudden’s outer clothing and reach the watch.

But would it really take 72 minutes?

It’s hard to know which version to believe. Fortunately, there was a third clock ticking, a biological one – one whose accuracy could not be influenced by human maintenance or clothing. That clock, visible on Dr. Gudden’s death mask, sets the pocket watch discrepancy in a new light.

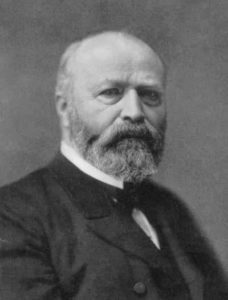

Dr. Bernhard von Gudden. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Dr. Gudden’s death mask

For decades, Dr. Gudden’s death mask disappeared among stored and boxed items of the Rosenheim Museum in Munich. A worker rediscovered it in 1999 and it became the subject of an exhibition in 2014.

The mask shows injury to Dr. Gudden’s face. His right eye – the left one from the viewer’s perspective – is visibly swollen. The Rosenheim Museum could not provide me with an image I could use for this post, but you can view the swelling in this German talk show by forwarding to 2:13-17.

The eye injury on Dr. Gudden’s death mask is consistent with descriptions of Gudden’s face following his death. Dr. Heiß, the substitute district physician who assisted the investigating magistrate, noted blue coloring under the right eye and frontal eminence of the brow which appeared to be caused by a heavy blow from a fist. Two government officials described swelling above Dr. Gudden’s left eye (they probably meant left from their perspective). The psychiatry professor Dr. Grashey recorded a broad contusion on the right frontal eminence. Dr. Müller, Gudden’s assistant, noted “not insignificant” blue coloring, over the right eye, which he also thought might have been caused by a fist. Finally, a district commissioner made a similar observation. He found indications of a blow to Dr. Gudden’s right brow.

Antemortem, perimortem, or postmortem?

A pathologist today would try to categorize Dr. Gudden’s bruising according to when it happened – before, at the time of, or after his death. Generally speaking, injuries received before death show swelling. Once the circulatory system stops at death, injuries are less likely to swell. This means Dr. Gudden might have survived the blow to his eye for a period of time before he died. And that would underscore the pocket watch discrepancy.

But there are exceptions. Certain postmortem conditions can cause pseudo-bruising, lending an antemortem appearance to a postmortem injury. One such condition is the position of the body. Dr. Gudden floated face-down in the water for two to three hours before he was found, allowing blood to pool in his face. That pooling might have caused some swelling even after death. He was laid in a supine position after he was found, and that might have reserved the effects by the next day.