Robert Raymer's Blog, page 4

September 8, 2018

Beheaded on the Road to Nationhood: Sarawak Reclaimed—Part II

After being beheaded as Alan Lee in Road to Nationhood: Sarawak Reclaimed by Rentap and his war party, my head did not hurt at all nor was there any swelling, but that night I could feel the pain in my ribs—I must’ve cracked one when I fell several times while being killed—which made it difficult for me to sleep. Back in my twenties, I cracked a couple of ribs after getting kicked in taekwondo, so I knew there wasn’t a whole lot a doctor could do except X-ray it for confirmation and give you something for the pain. They used to wrap your chest but they stopped doing that decades ago. The pain was manageable; it only hurt when I laughed or slept or rose from sitting, so I opted not to see a doctor, but I did need to repair my black leather shoes. Maybe from all of the falling or banging it on the short steps at the Iban Longhouse, the sole in front started to come off. Since I was not needed until Saturday, my big day where I was to play several characters—the Governor of Singapore; John Brooke, who had been passed over in favour of Charles Brooke as the second White Rajah; and the younger version of Captain Henry Keppel, a British naval officer who had served in the Opium War and assisted the first White Rajah James Brooke’s campaign against the Borneo pirates and Iban warriors—I had plenty of time to find a shoe cobbler to fix the problem before I needed to wear them.

Throughout the day, I kept receiving photos of the shoot being posted on the WhatsApp Group. Some made me pause and wonder because they looked like myscenes. I knew there had been some changes on the shooting schedule and the call sheet, so I double checked Friday’s schedule to make sure my name was not on it. I thought, perhaps, I had missed it. Late that afternoon, I got a message from Mark to confirm that I needed transportation for Saturday. Then two hours later, Prisca contacted me and asked if I could drive out to the Sarawak Cultural Village on my own. Seems there was a problem with the tide for the boat scene and they needed to start shooting a lot sooner than planned. I needed to be there by 6:30 am, which meant I had to get up at 4:30 am if I wanted to make the 50 km journey from my house on time.

Throughout the day, I kept receiving photos of the shoot being posted on the WhatsApp Group. Some made me pause and wonder because they looked like myscenes. I knew there had been some changes on the shooting schedule and the call sheet, so I double checked Friday’s schedule to make sure my name was not on it. I thought, perhaps, I had missed it. Late that afternoon, I got a message from Mark to confirm that I needed transportation for Saturday. Then two hours later, Prisca contacted me and asked if I could drive out to the Sarawak Cultural Village on my own. Seems there was a problem with the tide for the boat scene and they needed to start shooting a lot sooner than planned. I needed to be there by 6:30 am, which meant I had to get up at 4:30 am if I wanted to make the 50 km journey from my house on time.My wife told me to take a new shortcut to Damai, via Pending, the opposite way we normally took, via Satok; both would head north on the other side of the Sarawak River. Last night it had rained and was still drizzling when I arrived at the Bidayuh Longhouse, the new base of operations at exactly 6:30 am.

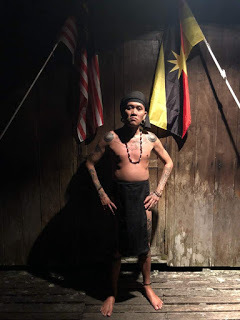

Alex and Charles Rentap (real name!)

Alex and Charles Rentap (real name!) I was told that all of the afternoon shoots had been cancelled, confirming my suspicions. Because yesterday, Friday, was a public holiday, the staff would not be around at the Bishop’s House, so they decided to create the shots they needed at the Sarawak Cultural Village using two other Caucasians, the Fort Guards, Alex and Charles for the Governor of Singapore and John Brooke.

I was told that all of the afternoon shoots had been cancelled, confirming my suspicions. Because yesterday, Friday, was a public holiday, the staff would not be around at the Bishop’s House, so they decided to create the shots they needed at the Sarawak Cultural Village using two other Caucasians, the Fort Guards, Alex and Charles for the Governor of Singapore and John Brooke.

Malaysia and Sarawak flagsSwapping roles at the last minute was quite common. Sometimes, someone couldn’t make it for the shoot, so they would grab whoever else was handy; others, as requested, sent a replacement for themselves. Jimmy, one of the extras, told me that he played nine roles. A little makeup, a change of costume, and he could pass for one race or another. Others played at least five or six roles, one or two primary, up-close shots, and the rest secondary to fill out the numbers.

Malaysia and Sarawak flagsSwapping roles at the last minute was quite common. Sometimes, someone couldn’t make it for the shoot, so they would grab whoever else was handy; others, as requested, sent a replacement for themselves. Jimmy, one of the extras, told me that he played nine roles. A little makeup, a change of costume, and he could pass for one race or another. Others played at least five or six roles, one or two primary, up-close shots, and the rest secondary to fill out the numbers. For the battle scenes, which took place last night, they made about a dozen people look like a hundred, taking multiple shots from different angles, catching various parts of their bodies. Those working on the actual footage reported how impressed they were seeing it on film.

For the battle scenes, which took place last night, they made about a dozen people look like a hundred, taking multiple shots from different angles, catching various parts of their bodies. Those working on the actual footage reported how impressed they were seeing it on film.

After we were dressed in our costumes, they drove Alex, who was to portray the 14-year-old Charles Brooke, and me, as the younger Captain Henry Keppel, to a nearby jetty in Santubong where we boarded a fishing boat with a trimmed down crew. Altogether, including the director, Fendi, and Rob, there might have been eight or nine of us. Since it looked like it was going to pour anytime soon, we were all in a rush to get set up and to start filming.

After we were dressed in our costumes, they drove Alex, who was to portray the 14-year-old Charles Brooke, and me, as the younger Captain Henry Keppel, to a nearby jetty in Santubong where we boarded a fishing boat with a trimmed down crew. Altogether, including the director, Fendi, and Rob, there might have been eight or nine of us. Since it looked like it was going to pour anytime soon, we were all in a rush to get set up and to start filming.

Fendi, the Director

Fendi, the Director

They had Alex and me stand at the bow, looking off toward our left, with the camera positioned behind us, shooting us, the sea and the blackening sky assuring us that a storm was approaching.

They had Alex and me stand at the bow, looking off toward our left, with the camera positioned behind us, shooting us, the sea and the blackening sky assuring us that a storm was approaching. While filming, I explained to the young Charles Brooke, the future second White Rajah of Sarawak that someday, all of this would be his….It was Charles Brooke who greatly expanded the territory of Sarawak beyond the original city of Kuching to its present borders.

While filming, I explained to the young Charles Brooke, the future second White Rajah of Sarawak that someday, all of this would be his….It was Charles Brooke who greatly expanded the territory of Sarawak beyond the original city of Kuching to its present borders.  Luckily for me, I wore a hat when it began to drizzle; unluckily, the British flag that they had mounted kept pushing at the back of my head nearly knocking it off before they tied the flag down. To get the angle they were looking for, we had to kneel on the deck, with our backs erect. The position was uncomfortable, so we were glad when the director suggested that we remove our shoes, which helped.

Luckily for me, I wore a hat when it began to drizzle; unluckily, the British flag that they had mounted kept pushing at the back of my head nearly knocking it off before they tied the flag down. To get the angle they were looking for, we had to kneel on the deck, with our backs erect. The position was uncomfortable, so we were glad when the director suggested that we remove our shoes, which helped.

Later, when it began to rain heavily after the shooting, the hat flew off my head, but I managed to catch it midair before it was lost forever at sea.

Later, when it began to rain heavily after the shooting, the hat flew off my head, but I managed to catch it midair before it was lost forever at sea.

Author Robert Raymer and Rob Nevis, Executive Producer

Author Robert Raymer and Rob Nevis, Executive ProducerI had planned to get some shots of the fishing boat that we had used but the heavy rain prevented me from doing so; I wished I had taken the shots before boarding but we were in a rush to beat the rain....Alex and I returned to the Bidayuh Longhouse, while the others stayed behind to shoot more river footage.

They then spend the rest of the day and the following day taking B-roll shots—outtakes without actors—at notable sites such as Fort Margherita, the Istana, the Courthouse, and other historical buildings, and the surrounding environs to work into the documentary.

The A-roll shots are the main scenes with the actors and extras, the most costly part of the filming, which is why they try to cram it all into several long days for documentaries or a few intense weeks for feature films.

Rob Nevis and Jason Brooke

Rob Nevis and Jason BrookeBefore leaving Kuching, Rob managed to have tea with Jason Brooke, grandson of the last Rajah Muda of Sarawak.

Even though the rescheduling of the shoot made me miss out on some important scenes, including having a private tea with James Brooke as the Governor of Singapore, no doubt suggesting that he seek his fortune in Borneo, I was quite happy to keep my head about me at all times, just in case someone decided to, well, you know, this is land of the headhunters, and that Iban war party did kill me in that other scene…

It was also quite an honor to be a part of recreating history—an honor for all of us involved from the cast, the crew and production—in the Road to Nationhood: Sarawak Reclaimed.

# # # Beheaded on Road to Nationhood: Sarawak Reclaimed—Part I

Road to Nationhood: Journey to Independence part I (1945-1957)

Road to Nationhood: Journey to Independence part II (1957-1965)

Maugham and Me —Borneo Expat Writer

Published on September 08, 2018 23:23

September 7, 2018

Beheaded on the Road to Nationhood: Sarawak Reclaimed—Part I

Robert Raymer and actors, Road to Nationhood: Sarawak Reclaimed

Robert Raymer and actors, Road to Nationhood: Sarawak Reclaimed Last year I was in a French documentary discussing Somerset Maugham, but this year I found myself getting beheaded in the Malaysian documentary Road to Nationhood: Sarawak Reclaimed. The documentary, a Rack Focus Films production, is the third season in the highly successful Road to Nationhood series and was originally scheduled to be aired 16 September 2018—on Malaysia National Day—on the National Geographic channel, Astro, though more likely it would be aired in October.

In 1963, on 16 September, Malaysia was formed with Singapore, North Borneo (Sabah) and the Sarawak Crown Colonies, joining the Federation of Malaya. Singapore separated from Malaysia to become an independent republic in 1965.

While living in Penang I was an extra in several notable Hollywood films, such an Anna and the King, Paradise Road, Beyond Rangoon, and the French film Indochine. It was on the set of Indochine—Oscar winner in 1993 for Best Foreign Language Film plus an Oscar nomination for Catherine Deneuve for Best Actress—where I met Rob Nevis

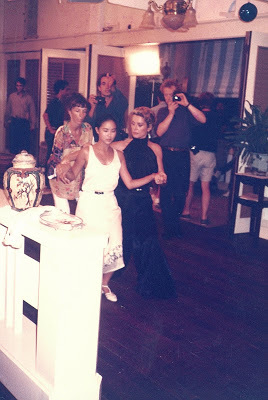

Christmas Party scene, Indochine

Christmas Party scene, Indochine  Catherine Deneuve and Linh Dan Pham, Indochine

Catherine Deneuve and Linh Dan Pham, Indochine  Rob Nevis, center, on the set of Paradise Road

Rob Nevis, center, on the set of Paradise RoadBack then, Rob worked with Film Location Services, but now he was a producer with Rack Focus Films. A few months ago, Rob contacted me and we met in Kuching where he told me about the project and asked if I would be interested to take on a role, possibly Charles Brooke, the second of three White Rajahs—they ruled Sarawak for one hundred years from 1841 to 1946.

Charles Brooke and author

Charles Brooke and author

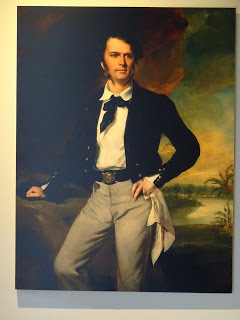

James Brooke

James BrookeThe first White Rajah was an Englishman James Brooke. After helping the Sultanate of Brunei fight piracy and an insurgency among the Dayaks, he was rewarded the city of Kuching. The third and last White Rajah, Charles Vyner Brooke, was mostly an absentee ruler. Following the Japanese Occupation, he controversially ceded Sarawak to Great Britain at a time when they were shedding their British Empire.

Giovanni and Ivan at center

Giovanni and Ivan at center

Giovanni as James Brooke

Giovanni as James BrookeAfter finding Ivan, a Hungarian friend who is more muscular and younger, to play Charles Brooke, and Giovanni, an Italian who is taller and younger to play James Brooke, I was asked to portray various colonial officers and officials. My first role would be Alan Lee, a colonial officer, who unfortunately was killed during a battle with Rentap’s Iban warriors.

Alan Lee’s beheading proved to be a turning point in the Rajah Brooke’s determination to capture or kill Rentap (which he never did—his famous quote was “still alive, still fighting”) and defeat the Saribas and Skrang Ibans, notorious headhunters who routinely attacked Bidayuh settlements throughout Sarawak including Quop, where my wife is from—decimating the population.

Several days before filming began the cast were called to Kayu Malam Productions, opposite of Crown Square, for wardrobe fitting and briefing by the director, Fendi, and Rob, our executive producer. This was the first time that the Kuching group would be meeting the Kuala Lumpur group (Rack Focus Production) and those they brought in from KL to assist them, like Johnny Goh, Prop Master.

Bani making adjustments

Bani making adjustments Johnny Goh and Rob Nevis

Johnny Goh and Rob Nevis Bani, Wardrobe

Bani, WardrobeBani, in charge of Wardrobe, separated us by groups: Iban warriors, Chinese miners, Istana people, Malay extras, and a handful of Caucasians portraying Colonial Officers, Captains and Fort Guards. While waiting around, we took photos of one another in various costumes. The heavy wool coat that I tried on looked good; however, it was a little long in the sleeve and rather impractical for the tropical Sarawak climate.

Robert and Giovanni

Robert and GiovanniDuring the briefing we were told that, unlike feature films, the budget for documentaries was minuscule, so compromises had to be made—there wouldn’t be endless takes from all angles. Also Part III of the series would be the most difficult to film. Road to Nationhood Part I (1945-1957) and Part II (1957-1965) were largely made from historical archives, but since there were very little archives for early Sarawak, scenes had to be re-enacted, hence the need for actors and extras. I was told we would not be speaking (only perceived to be speaking or having a discussion) while a narrator pointed out the historical significance of what was being viewed.

Filming was originally scheduled to begin near the end of July but had to be pushed back a month because the production permits for filming in Sarawak were held up. The French crew had the same problem. For this project, it would be a bigproblem, which meant the time for post-production was being compressed. The moment all of the footage was shot for a particular scene, it had to be sent, without delay, to post production to work on and be pieced into the documentary. Unfortunately, films or documentaries were rarely, if ever, shot sequentially.

Jimmy, one of the extras, set up a WhatsApp Group so we would all be in the loop, which made it easier for Prisca, Unit Production Manager, to find someone, or for Mark, Transport Manager, to clarify who needed transportation to Sarawak Cultural Village, where most of the shooting would take place. Jimmy, Prisca and others posted photographs throughout the shoot and gave me permission to use some here, which I greatly appreciated.

Jimmy

Jimmy Prisca and escorts

Prisca and escortsAlthough shooting began on 28 August 2018, I wasn’t called in until two days later on Thursday, 30 August, for my first scene. Thanks to all of the photos from the shooting posted on the WhatsApp Group, I could keep up with the filming. Since it was a relatively small cast, about 30 of us, with everyone playing multiple roles, I recognized many of the faces from our previous meeting.

We were told to be at Kayu Malam Productions by 7 am, so I was up at 5 am to avoid all of the school traffic. En route to Damai, three otters ran across the road in front of our van, which I took as a good sign. Not long after we arrived at the Iban Longhouse in the Sarawak Cultural Village, our base of operations, Bani and Sheila from Wardrobe outfitted the Iban Warriors and then the makeup crew and the tattoo specialist led by Dedek, got to work, creating some elaborate Borneo tattoo patterns all over their bodies including the exposed parts on their upper thighs and buttocks. Others tried on wigs.

As we sat there waiting for our turn, extras in their respective native outfits would walk by carrying shields and spears and swords or rifles. All of the Chinese characters, I noticed from the photos taken on the first two days, had the front half of their heads shaved and a long queue added to their hair, fitting the Manchu style back in the 1840’s. Some of the Ibans had their hair cut as if someone had used a bowl.

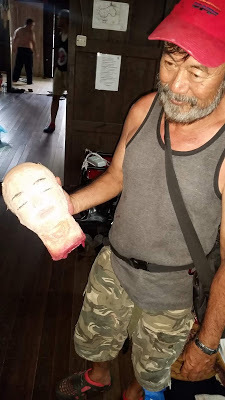

Johnny showed me my head that he made and asked, “Does this look familiar?”

At the briefing we were told to expect a lot of waiting, something I had experienced on previous productions. Luckily I had brought a book, though mostly I talked with others in the cast and the crew, getting to know them; we were also free to roam around the set and watch other scenes being shot, which I gladly did.

Ivan Evetonics as Charles Brooke

Ivan Evetonics as Charles Brooke“Can you see the camera?” the director called out to Ivan, who was portraying Charles Brooke, surrounded by extras. “If you can see the camera, then the camera can see you.”

During the previous meeting, I met the actor who would portray Rentap, the leader of the Skrang Ibans, who was quite large like the real Rentap, but then he was replaced by Ernesto Kalum, a world-renown tattoo specialist with a London law degree, who looked a whole lot more fierce….Later, when I was introduced to Ernesto on the set, I was told, “This is the man who is going to behead you.”

Ernesto Kalum as Rentap

Ernesto Kalum as RentapI was unaware that my scene was a night shoot, so I could’ve come a lot later. Several others like me had to wait all day….Twelve hours would pass before I was finally asked to get into my costume—white shirt, blue trousers, gray cap. I was asked to bring my own black leather shoes. Although we were supposed to finish the day at 9:00 pm we didn’t finish shooting until 10:30 pm.

While waiting for the other scenes to finish, I posed for a few shots with Rentap and his Iban war party before they had a chance to behead me.

While waiting for the other scenes to finish, I posed for a few shots with Rentap and his Iban war party before they had a chance to behead me.

I could see the fort area where I would be killed.

Then I heard Fendi, our director, call out, “Bring the dying man.”

He was referring to me, but it sounded like I had some incurable disease….In position, we watched the Iban war party approach the makeshift fort. One of the Fort Guards, Alex appeared but went one way, while the war party, who had been hiding, went the other. Before I was called in to be killed, they gave one of the warriors, Watt, a real Iban sword, and they had him swing down hard on what appeared to be a coconut, as if he were chopping off my head. Once that segment was completed, they switched out the real sword for one made of plastic.

Watt and wife (real)

Watt and wife (real)When it was my turn to come on, I removed my glasses, which made it difficult to see. Previously, I wore contacts. The director told me to ditch my hat, so I tossed it aside. Meanwhile someone marked my position in front of the camera with an upturned leaf that I could not see without my glasses. All the leaves seemed to blend in together, plus it was dark outside. An assistant and the cameraman kept telling me to stop “here” at a particular leaf for a close up shot of my being killed. Without my glasses I couldn’t quite see which particular leaf they were pointing to. For a close-up shot, an inch here or there made a huge difference.

“What seems to be the problem?” asked the director, and someone explained that I couldn’t see the leaf without my glasses.

Finally someone set down a white folder just out of camera range and told me to stop just before the folder. No problem, I could see that. The director then asked me to breathe heavily as if I feared for my life. I was to stop at my spot, pivot, look right and then left….We ran through the sequence a few times. When I turned to look right, and then left, the Iban warrior would come up from behind me and bring down his sword.

Before the actual filming began, I approached Watt and felt the sword to make sure he did in fact switch them, prompting laughs from everyone watching, about twenty-five people including the extras and technicians. I definitely didn’t want any untoward mishaps involving my head.

The first run through, Watt clipped my ear with his sword and it stung a little. He duly apologized.

Fendi asked me to fall to the ground the moment I got hit, which I did. I thought I was pretty convincing. Maybe too convincing because it suddenly hurt around the ribs; I must’ve landed on my elbow while trying to protect my glasses secured in a pouch inside my shirt, not wanting to crush it. We did two or three more takes and the last one, Watt got me pretty good on the side of the head. It sounded really loud. There was this startled hush when I collapsed as if I really had been killed. I stayed down a long time for dramatic effect thinking perhaps Watt was a little too realistic on that last one, hoping there would be no more takes, not sure how many more blows my head could take.

This is not me, but you get the idea.

When the director called, “Cut!” everyone, no doubt, thought I really did get cut by that sword. They all heard the impact on my head and saw me drop dead, again rather convincing if I don’t say so myself. Watt kept apologizing profusely. He told me he couldn’t stop the momentum of his swing in time. Luckily he was not using a real sword or I would not be writing this.

Several people rushed over to make sure I was in fact okay. I kept assuring them I was fine.

“See, no blood,” I said.

The blood would come next. Not mine, but the blood mixture meant for my substitute head. The director took a closer look at that head. Although the face did look like me, they got the hair wrong. I tried to point it out earlier to Johnny before they attached the hair, but he assured me that the thick black hair didn’t matter because it would soon be covered with blood. Still, I thought, it looked way too thick—blood or no blood.

The director didn’t like the way-too-thick black hair either and asked if it could be cut from the head. Then they decided not to use the head in that scene, since it was pretty obvious when Watt got me the last time, he had severed my head. Not wanting to waste the head and the blood that they were applying, someone suggested it could be used for a scene with a crocodile at a nearby swamp. So they carried away my former head and covered it with more blood and filmed it by the swamp.

In a later scene, Iban warriors were seen carrying away their heads in makeshift holders.

As for me, as I walked off the set, I carried my own head exactly where it belonged—on top of my shoulders.# # #

Road to Nationhood—Part IRoad to Nationhood—Part II

—Borneo Expat Writer Beheaded on Road to Nationhood: Sarawak Reclaimed—Part II (available soon)

Maugham and Me

Published on September 07, 2018 01:58

August 7, 2018

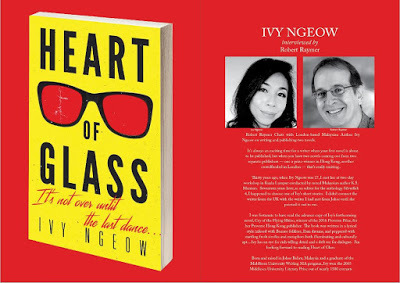

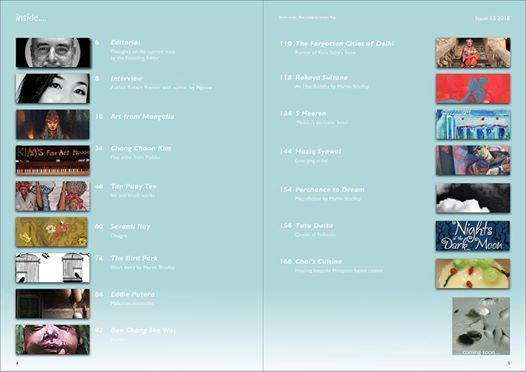

My Interview with Ivy Ngeow is in Blue Lotus 13

My interview with Ivy Ngeow, author of Cry of the Flying Rhino, winner of Proverse Prize and Heart of Glass, has been published in Blue Lotus 13.

Also appearing in the issue:

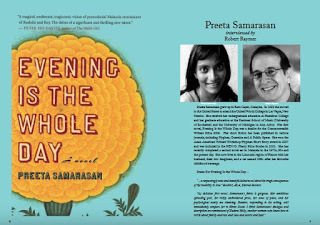

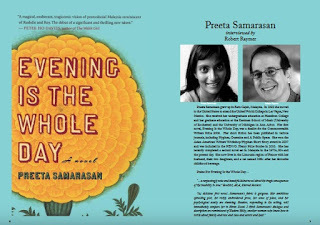

My interview with Preeta Samarasan, author of Evening is the Whole Day, was published in Blue Lotus 12, pages 8-21.

Five part Maugham and Me series

—Borneo Expat Writer

My other interviews with First Novelists

Golda Mowe author of Iban Dream and Iban Journey

Published on August 07, 2018 02:05

August 6, 2018

Faulkner-Wisdom Novel Awards—2018 Finalist for Novel: The Lonely Affair (and the Resurrection) of Jonathan Brady

The Pirate’s Alley Faulkner Society recently announced the short list finalist; although I missed out, The Lonely Affair (and the Resurrection) of Jonathan Brady was named a finalist and three other novels semi-finalist. This year they had 438 novels, 98% from the US.

The Lonely Affair (and the Resurrection) of Jonathan Brady had been a finalist in their 2014 and 2012 contest, a Quarter-finalist in 2012 Amazon Breakthrough, and won fourth place in 2008 National Writers Association novel contest), though under a different title. Over the years, while rewriting the novel, I went back and forth over the title.

Originally it was The Lonely Death of Jonathan Brady. Although his death was the culmination of the novel, at that point, the novel was more about his “affair”, so I changed the title to The Lonely Affair of Jonathan Brady. After rewriting the novel, overhauling it completely, I changed the title to The Resurrection of Jonathan Brady. Although the novel opened with his death, I resurrected his life by examining it, the year-long events that led up to his death, followed by his spiritual “resurrection” after his funeral. Then I switched the title again and simply called it The Lonely Affair. Nice and simple I thought, but then I rethought that the following year because the novel was not just about the affair, so I went back and forth between The Lonely Affair of Jonathan Brady and The Resurrection of Jonathan Brady. Finally I hit on a perfect compromise, which fully encapsulates the novel since it’s about both: The Lonely Affair (and the Resurrection) of Jonathan Brady.

Here is the synopsis:

During Cabrina Chaval’s debut in The Magic Flute,Jonathan Brady was only sixteen years old, too young to understand the implications of that look — the way she poured out her heart, her soul to him. Twenty-two years later, she bumps into him and invites him to paint her house. Yet Jonathan knows her true intentions. She wants him to rescue her from her failing marriage so they can be together. Through a series of coincidences, Jonathan is convinced that Cabrina Chaval is not only pursuing him but also deeply in love. Because of her prominent position in society and the fact that she’s married, Jonathan accepts that their love, for now, must be kept secret.Recapturing the innocent love between two sixteen year olds and coming to terms with the loss of a domineering mother, Jonathan Brady’s delusion takes him through five distinct stages of love — Heightened Awareness, Playful Pursuit, Courtship and Romance, Jealousy and Suspicion, Reconciliation and Acceptance — all unbeknown to Cabrina Chaval.After some soul-searching about the state of her marriage, Cabrina Chaval resurrects Jonathan Brady’s life and, in the process, elevates his love for her to its penultimate stage — Eternal Love. —Borneo Expat Writer

Published on August 06, 2018 01:25

June 6, 2018

Payah Books by Margaret Lim Will Soon to be Available as eBooks!

Margaret Lim, seated second from right, next to Sharnaz Saberi, host of Kuppa Kopi

Margaret Lim, seated second from right, next to Sharnaz Saberi, host of Kuppa KopiGood news for fans of Margaret Lim, the author of Sarawak-set children stories about Payah that I blogged about last year. Her four Payah books and other stories are being made available as e-Books. The books will be released on her birthday, 23 June 2018; however, pre-orders are available now.

The Borneo Post called Payah, “A uniquely Sarawakian children’s book that will fire a child’s imagination. A must read for all!”

PayahPayah is about a fearless Kayan girl called Payah, who has a soft heart for small helpless creatures. Deep in the rainforest of Sarawak, Payah rescues a hornbill and a mouse deer, while still taking care of a baby orangutan.Four EyesPayah makes a surprising discovery, and takes on a responsibility that becomes almost too much for her to bear when she befriends a run-away.Precious Jade and Turnip HeadPayah celebrates Chinese New Year with her classmate, Precious Jade, and her little brother Turnip Head, who keeps getting himself and Payah’s friend into trouble.Nonah, or The Ghost of Gunung MuluPayah befriends Nonah, after she joins her parents who teach in the rainforest. They win a trip to Mulu Caves, where they help to unravel a plot to steal rare orchids.Here is the Amazon link to the currently available books. Printed versions might be available on Amazon in the future, as well.

The children of Margaret Lim have also prepared a beautiful new website, Sarawak Stories, to honor her and her writing: There, you can still read the Payah books for free until they have to be removed and replaced with the Amazon link by 23 June 2018.

Other stories by Margaret will remain free on that website. —BorneoExpatWriter

Interview with Golda Mowe, author of Iban Dreams and Iban Journey, another Sarawakian writer who has also written a book for children.

Published on June 06, 2018 20:43

May 23, 2018

My Being Interviewed on Short Stories by Terence Toh

Here is the full interview on crafting, writing and selling short stories that I recently did for Terence Toh for his article “The Long and Short of it” in The Star. Some of the best stuff was left out since it featured several other writers and readers.

1. Why do you enjoy writing short stories?

When I first began to write, I would spend 15 minutes every day randomly describing something by carefully observing my surroundings, whether I was at home, eating outside, waiting at a bus stop or inside a bank. Most of the short stories that I wrote for my Popular Readers Choice Award winning collection Lovers and Strangers Revisited began that way. I didn’t set out to write a short story, yet by merely observing my surroundings, an idea would take hold and I would stay with it for as long as it took to rough out a first draft. What an unexpected joy — turning an exercise into a short story in a couple of hours. Now that you have a new story, you got something to work with…which is a whole lot more enjoyable than staring at a blank page.

When I first began to write, I would spend 15 minutes every day randomly describing something by carefully observing my surroundings, whether I was at home, eating outside, waiting at a bus stop or inside a bank. Most of the short stories that I wrote for my Popular Readers Choice Award winning collection Lovers and Strangers Revisited began that way. I didn’t set out to write a short story, yet by merely observing my surroundings, an idea would take hold and I would stay with it for as long as it took to rough out a first draft. What an unexpected joy — turning an exercise into a short story in a couple of hours. Now that you have a new story, you got something to work with…which is a whole lot more enjoyable than staring at a blank page.2. How is the process of writing and editing a short story different from other forms of writing, eg. novels?

A short story, like a good poem, has a singular effect, a singular voice. Novels can by rangy and loose. Short stories are taut, no wasted words are allowed, no digressions. Being short, about 8-25 pages, it can be roughed out and polished in a matter of days, weeks, whereas a novel takes months, years. It takes a lot of patience. Sometimes it feels like you’re digging a ditch, day after day, week after week, month after month, but you just got to keep on digging until you reach the end of that novel, then you got to revise and edit it, draft after draft. Far too many writers give up after the initial inspiration dries up. God, this is taking forever!

3. In your opinion, what elements should a great short story have?

A well-crafted short story has it all: tight writing, great imagery, apt descriptions, resonating mood, controlling theme, memorable characters, plus a logical, well-thought out, plausible story even if its fantasy or science fiction. It has a singular effect driven to an inevitable conclusion even if we never saw it coming, leaving the reader feeling utterly satisfied.

4. What is the greatest challenge of creating a memorable short story?

The biggest challenge is creating an effective story with a unified theme that holds it all together, something that resonates deeply with the reader. We have to show this (as if we’re watching a play or a movie unfold), not tell, and the reader doesn’t often see this over-arching theme until the final resolution, something else they didn’t see coming, despite it being a logical culmination based on what came before….Too many beginning writers try to trick the reader to show how “clever” they are; but in fact they’ve cheated the reader by creating an implausible ending that leaves the reader scratching his head and thinking, “Huh?” Whereas, a memorable short story is based on logic, even if the ending is unexpected, yet the clues, the inner workings of the story, the cause and effects of the characters’ actions, were all in place. We’re left thinking, “Wow, great story!”

5. How is the reception like for short stories in Malaysia? (compared to other parts of the world, if you are familiar with them?)

I think it’s wonderful what Amir Muhammad is doing with Fixi Novo, creating outlets for local writers. It’s one thing to be published online, another to hold a book with your story in it. On-line publishers, however, often have a greater reach….Markets in Malaysia (and around the world) have always come and gone. Back in the late 80’s/early 90’s many of my short stories were published in Her Worldand Female and other local magazines here and in Singapore that published short stories every month; but then they dried up. Others would appear and disappear. Recently Esquire Malaysia published fiction, but then stopped. I used to go to newsstands and scour local magazines to see if any new markets have appeared; now writers can do that by Googling….It was great when Raman Krishnan came out with his Silverfish anthologies and then began publishing short story collections by Malaysian writers. MPH has also been very successful. The markets and publishers are there; they may come and go, but the writer has to look for them, just like writers do all over the world. Malaysian writers can even submit their stories overseas online. I’ve had Malaysian-set short stories published in twelve countries.

—Borneo Expat Writer

My interviews with other writers on their first novels:

Ivy Ngeow author of Cry of the Flying Rhino, winner of the 2016 Proverse Prize. Golda Mowe author of Iban Dream and Iban JourneyPreeta Samarasan, author of Evening is the Whole Day, finalist for the Commonwealth Writers Prize 2009.

Five part Maugham and Me series

Published on May 23, 2018 17:12

May 17, 2018

The long and short of it by Terence Toh, The Star 6 May 2018

[image error] Do short stories get short shrift in Malaysia, or is brevity really the soul of wit? We find out what authors and readers have to say.

Malaysian authors, publishers and readers discuss the long and short of short story collections.

THE greatest short story in the world is only six words long: “For sale: Baby shoes, never worn”.

The author of that punch to the gut has never been officially identified but the story is often attributed to Ernest Hemingway, the American author renowned for succint prose expressed in short, declarative sentences.

Sometimes, less really is more. These words are the mantra of the short story writer, who often manages to create wonderful worlds, with their own beginnings, middle and ends, with the same number of words a novelist would use to introduce a single character or describe one scene.

Compared to novels, however, it seems like short stories are often considered “lesser” than longer works. So what exactly goes into the creation of a good short story? And do readers like them?We asked some local short story writers, publishers and fans to find out.

The editors :

“Short story collections have played second fiddle to novels for a long time, whether in Malaysia or international markets,” says Chua Kok Yee, author and co-editor of the recent horror anthology Remang And Other Ghostly Tales.

He points to Fixi, one of the popular imprints from indie publisher Amir Muhammad.

“Using Fixi’s topsellers list as the bellwether, we can see that novels are outselling collections of short stories. That said, it is heartening to see five out of 10 nominees for fiction in this year’s Readers’ Choice Awards are collections of short stories. It was the same number in last year’s edition of the award, so maybe local readers’ acceptance of short stories is on the rise,” he says.

Chua is referring to this year’s Popular-The Star Readers’ Choice Awards for which 10 fiction and 10 nonfiction titles have been nominated; nominees are chosen from last year’s bestselling local titles in Popular and Harris bookstores nationwide, so we know that Malaysians bought a lot of anthologies in 2017.

But could that be because the industry is simply not putting novels out?

Amir, whose imprints Fixi and Fixi Novo publish Malay and English fiction respectively, says not many people publish novels in Malaysia, which results in many short story collections floating around.

Despite this, however, he thinks that most locals prefer longer and meatier works – “It’s the difference between having an entire self-contained nasi lemak versus eating 20 keropok,” as he puts it.

Many of the short story anthologies he publishes don’t sell even 5,000 copies, Amir says, though he adds that there are exceptions, such as KL Noir: Red (2013), which sold 18,000 copies, and Tunku Halim’s Horror Stories (2014), which sold 32,000.

Famous names and popular genres tend to sell more copies, he points out. “Names that are unknown now can always become famous later, just due to one book published later. Mankind needs hope to survive,” he says, tongue-in-cheek.

The writers :

[image error] According to author Robert Raymer, markets for short stories in Malaysia often came and went.

“Back in the late 1980s/early 1990s many of my short stories were published in Her World and Female and other local magazines here and in Singapore. They published short stories every month; but then they dried up. Others would appear and disappear. “Recently, Esquire Malaysia magazine began publishing fiction, but then stopped,” Raymer says via e-mail from Kuching where he has been based for 12 years.

A more globalised world, however, means that Malaysians are free to promote their short stories in many more exciting venues.

“The markets and publishers are there; they may come and go, but the writer has to look for them, just like writers do all over the world. Malaysian writers can even submit their stories overseas online. I’ve had Malaysia-set short stories published in 12 countries,” Raymer says.

He has written several anthologies, including Lovers And Strangers Revisited (2008), which was a winner in the 2009 Readers’ Choice Awards.

When it comes to writing short stories, you probably can’t get any shorter than the works in Micro Malaysians (2017), a book of micro-fiction: none of the stories in it is over 150 words long. Editor Anwar Hadi, who curated the works, says it takes a tremendous amount of skill to do well in so little space.

“I think writers are freer to explore their weirder ideas in short stories than they are in longer forms of writing. They don’t have to dedicate as much time to writing short stories as they would novels, so greater risks in writing can be taken.

“The cost in terms of time isn’t as heavy, and I think we readers can be on the receiving end of those riskier pieces and be more expansive in our reading in the process,” Anwar says in an e-mail interview. Chua agrees with this.

“For the reader, short story collections require less of an investment in time and emotions compared to a novel. We can finish a story within 15 minutes or half an hour, and then do something else before starting the next one.

“It is much harder to do that if you are reading a good novel. Many readers would have experienced this; you start reading a novel, and then have to say goodbye to your social life for the next few days or weeks!” he says.

Raymer feels that one of the delights of creating short stories is how they take less time than novels.“A short story, like a good poem, has a singular effect, a singular voice. Novels can be rangy and loose. Short stories are taut, no wasted words are allowed, no digressions.

“Being short, about eight to 25 pages, it can be roughed out and polished in a matter of days, weeks, whereas a novel can take months, years even. It takes a lot of patience,” he says.

The readers :

As it turns out, Malaysians are also fond of short story anthologies. Some readers, however feel that anthologies often get the short end of the stick compared to longer works.

“I do think short story collections are generally less celebrated and less effort is put into marketing them. I think they are unfairly dismissed as a gateway medium for novice writers. There’s a certain privileging of the novel format as the ultimate medium of literature,” says avid reader Diana Yeong, 43.

Yeong says while she doesn’t actively seek out short story collections, she doesn’t shy away from them either. Some of her favourite collections included Patricia McKillip’s Dreams Of Distant Shores (2016), Ted Chiang’s Stories Of Your Life And Others (2010) and Ken Liu’s The Paper Menagerie And Other Stories (2011). “Collections can be hit and miss and more often than not will have at least a couple that miss the mark, and only one or two in the entire collection that have that ‘wow’ factor,” Yeong says.

“There’s an element of delicious surprise going into each story, which is a nice contrast with the immersive nature of novel reading. I like diving deep into characters and places and situations with novels, but short stories are a refreshing change of pace.”

Honey Ahmad, 41, thinks that short story collections are a great way to get to know a new author. She often reads collections online, especially when in the mood for a break. At the moment, she’s reading Miranda July’s Stories and John Connolly’s Night Music. Among her favorite collections are Jhumpa Lahiri’s Intepreter Of Maladies, Lara Vapnyar’s Brocolli And Other Tales Of Food And Love.

“Annie Proulx also writes spare and beautiful short prose. For horror I love Joe Hill’s stuff and in fantasy George R.R. Martin writes some of the best fantasy shorts out there. I also love Ted Chiang’s shorts too as he melds sci-fi, fantasy and the human condition so well in a short story form,” Honey said. “It is a different skill writing short stories. Often they take you down surprising places and I love how a good story can be told with few words. That takes mad skills.” --Borneo Expat Writer

Published on May 17, 2018 03:46

April 7, 2018

My Preeta Samarasan interview in Blue Lotus 12

My interview with Preeta Samarasan, author of Evening is the Whole Day, has been published in Blue Lotus12, pages 8-21.

In the same issue there was an excerpt from Cry of the Flying Flying Rhino by Ivy Ngeow, whom I had also interviewed.

Congrats to both Preeta and Ivy!

—Borneo Expat Writer

My other interviews with First Novelists:

Golda Mowe author of Iban Dream and Iban Journey.

Five part Maugham and Me series

Published on April 07, 2018 22:00

January 17, 2018

Ivy Ngeow: Asian Books Blog posted 500 words from Ivy about her book Cry of the Flying Rhino

Ivy Ngeow, who I recently interviewed and who interviewed me was asked to write 500 words about her book, Cry of the Flying Rhino.

Ivy Ngeow, who I recently interviewed and who interviewed me was asked to write 500 words about her book, Cry of the Flying Rhino.Asian Books blog wrote: Proverse Hong Kong is a publishing house with long-term, and expanding, regional and international connections. This week sees a double bill of posts about Proverse. Yesterday, Gillian Bickley, Proverse co-publisher, talked about the company's aims, and development. Today, Ivy Ngeow, winner of the 2016 Proverse Prize for Fiction, talks about her new novel, Cry of the Flying Rhino, which is published by the company.

Ivy was born and raised in Johor Bahru, Malaysia, but she studied in London, and her work - journalism and fiction - has appeared in many publications in Malaysia, Singapore, and the UK

Cry of the Flying Rhino is set in 1996, in Malaysia and Borneo. It is told from multiple viewpoints and in multiple voices. Malaysian Chinese family doctor Benjie Lee has had a careless one-night stand with his new employee – mysterious, teenage Talisa. Talisa’s arms are covered in elaborate tattoos, symbolic of great personal achievements among the Iban tribe in her native Borneo. Talisa falls pregnant, forcing Benjie to marry her. Benjie, who relished his previous life as a carefree, cosmopolitan bachelor, struggles to adapt to life as a husband and father. Meanwhile, Minos – an Iban who has languished ten years in a Borneo prison for a murder he didn’t commit – is released into English missionary Bernard’s care. One day, Minos and his fellow ex-convict Watan appear on Benjie's doorstep. Now Benjie must confront his wife’s true identity and ultimately his own fears.

So, over to Ivy…

Cry of the Flying Rhino was written thirteen years ago after I made my one and only trip to Borneo with my mother. I was inspired by the dark, macabre and gothic nature of communal longhouse living and the tribal civilisation and culture which have been around for thousands of years. Two things triggered some ideas.

Firstly, during the trip, I saw a tattoo parlour called Headhunters. It piqued my interest in the traditional art and symbolism of Iban tattooing, performed manually with a hammer, steel pin and ink made from tree ash.

Secondly, long after our trip, I dreamt of a girl in a longhouse with eyes as huge as the “hollows of the benuah tree”. Those words came to me in the dream. I wrote them down. She looked sad and haunted and there was also terror in her eyes. I did not know who she was or what the dream was about but something unpleasant and unusual had happened to her and I set about finding out about the Iban culture, which I later discovered, is based on dreams. That dreams were everything, our hopes, work, happiness and luck.

In exploring the two triggers above, I found out that indigenous cultures are threatened and dying, because of loss of habitat due to logging and deforestation, and due to the conversion of the Ibans to other religions. As a result, orang asli (original people) like the Ibans are forced to leave their habitat for the city because their livelihood, dependent on being able to survive in the jungles on the fat of the land, is diminishing due to the jungles being cleared. Their way of life which is so rich in folklore, superstition and traditions will soon be lost. Ultimately the rapid destruction of the jungles will impact upon the rest of the world via climate change and so on. I also found out that children tattooed children which ensured that the art would never die. If adults were one day wiped out by an epidemic or a massacre, the surviving children would all have learned and mastered all survival and artistic skills including tattooing.

Cry of the Flying Rhino is a modern novel set in the railway town of Segamat, which has already been deforested and turned into miles of plantation, and Borneo, whose jungles are under threat. The Chinese GP, Benjie, has been forced to marry Talisa, a mysterious and tattooed teenager, and the adopted daughter of wealthy crass Scottish landowner Ian. Benjie has to discover for himself his wife’s true identity, when Minos and Watan, two Ibans who leave the jungle and appear in Segamat one day, looking for Talisa.

Cry of the Flying Rhino raises uneasy themes of identity, poverty, religion, race, greed, colonialism and post-colonial struggles, and deculturalisation because I want to convey to readers the issues and conflicts which affect Asia today using the medium of fiction. I hope the story will take them to another world.

Details

Cry of the Flying Rhino is published by Proverse, in paperback, priced in local currencies.

Asian Books Blog Book of the Lunar Year in the Year of the Rooster

Don't forget Asian Books Blog is currently running a poll to find its Book of the Lunar Year. To vote e-mail the title of your one choice for the winner to asianbooksblogvoting@gmail.com. Voting closes at 5pm on February 15th.

Congrats to Ivy and all of the attention that she has been receiving for her first novel Cry of the Flying Rhino!

For SIGNED FIRST LIMITED EDITIONS of Cry of the Flying Rhino

For book orders:

Paperback: amazon.com

Paperback: amazon.co.uk

Kindle eBook: US

Kindle eBook UK

NEW author pages! See below:

Amazon author’s page

Goodreads author’s page

Ivy Ngeow interviewing Robert Raymer

My other interviews with First Novelists:

Golda Mowe author of Iban Dream and Iban Journey.

Preeta Samarasan, author of Evening is the Whole Day, finalist for the Commonwealth Writers Prize 2009.

Five part Maugham and Me series

Published on January 17, 2018 16:04

January 5, 2018

INTERVIEW PREETA SAMARASAN: Robert Raymer chats with French-based Malaysian Writer Preeta Samarasan

Preeta Samarasan, photo by V.V. Ganeshananthan

Preeta Samarasan, photo by V.V. Ganeshananthan I have yet to meet with Preeta Samarasan, author of Evening is the Whole Day; however, I do have two connections. First, when Lovers and Strangers Revisited beat out Preeta’s Evening is the Whole Day and Tan Twan Eng’s The Gift of Rain for the 2009 Popular Reader’s Choice Awards here in Malaysia, no one was more surprised than me. I thought those two had a lock on the first two places and I was just hoping to sneak into third place. The trophy, by the way, was pretty cool, with the cover of my book on it, so I gladly accepted it. Still I feel those two books — both novels published overseas — were more worthy.

The second connection is that I spent a lot of time in Ann Arbor and on campus where Preeta did her MFA in Creative Writing at the University of Michigan. Not only did I set up a Kinko’s store there in the early 80’s (did the contracting, hired and trained the staff and set a national sales record for the first month out of 600 stores), I also had a brother who lived there for a couple of years. Growing up in Ohio I was naturally a big fan of the Buckeyes over the Wolverines, huge football rivals, so I hope Preeta doesn’t hold that against me...

Preeta Samarasan grew up in Ipoh. In 1992 she moved to the United States to attend the United World College in Las Vegas, New Mexico. She received her undergraduate education at Hamilton College and her graduate education at the Eastman School of Music (University of Rochester) and the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. Her first novel, Evening Is the Whole Day, was a finalist for the Commonwealth Writers Prize 2009. Her short fiction has been published in various journals, including Hyphen, Guernica and A Public Space. She won the Asian American Writers’ Workshop/Hyphen Short Story award in 2007 and was included in the PEN/O. Henry Prize Stories in 2010. She has recently completed a second novel set in Malaysia in the 1970s, 80s and the present day. She now lives in the Limousin region of France with her husband, their two daughters, and a cat named Milo after her favourite childhood beverage.

Praise For Evening Is the Whole Day…“... a surpassingly wise and beautiful debut novel about the tragic consequences of the inability to love.” Booklist, ALA, Starred Review

"(a) delicious first novel...Samarasan's fabric is gorgeous. Her ambitious spiraling plot, her richly embroidered prose, her sense of place, and her psychological acuity are stunning. Readers, responding to the setting, will immediately compare her to Kiran Desai. I think Samarasan's dialogue and description are reminiscent of Eudora Welty, another woman who knew how to write about family and race and class and secrets and heat." The New York Times Book Review

RR: Preeta, I loved how you played with time in Evening is the Whole Day, how you flashed forward about Chellam and how you kept going further back in time. Personally I felt the structure worked, how each succeeding chapter depicts an earlier event and undercuts what we had just learned, often destroying our pre-conceived ideas as to what we thought had happened based on innuendo and snide comments made by the other characters. We’re like, oh, so that’s how it began and would feel guilty (at least I did) for jumping to conclusions. It feels like you’re peeling another layer off that onion to finally get to the core of the truth, to the events that led up to the beginning. Was this something you wrestled with as opposed to writing the story chronologically? Was this your original intended structure or did you change it while writing the first draft, or immediately afterwards? (I would think you would need to write the whole story before you could rearrange timelines in the way that you did; either way, great effect!)

Preeta: I tried out a lot of different structures before hitting upon that one. Of course the first thing I tried was the most obvious and the most common (for good reason — it works well for many stories!): a simple linear narrative moving chronologically forward. But really I had two stories to tell, the Now and the Then, and I wanted them to unfold simultaneously so that they could inform and colour each other. So pretty early on I realised that I had to alternate between those two timelines. And then, fairly late into the process of writing the novel, I saw that I would have to tell the Now story backwards, because I really just wanted to show the reader what happens at the end, and I wanted them to keep reading in order to find out why and how.

RR: I heard it took you nine years to write Evening is the Whole Day. Of that time, how long did it actually take you to write a complete first draft (no matter how rough that first effort was to get to ‘the end’)? Other than the structure and the time element, what other difficulties did you encounter while telling the story over the subsequent revisions?

Preeta: This is all so long ago now that I am honestly having trouble remembering all the different milestones! It doesn’t help that I have now, for an equal amount of time, being working on a different project. But I think that I did not have a complete first draft of Evening is the Whole Day until the end of my time at the University of Michigan MFA program, so that must mean I didn’t have a full draft until year seven….I think the structure was the most challenging thing to figure out; the voice and the plot were pretty well settled from very early on. The only other difficulty was trimming all the extraneous material from the draft, because the novel was much, much longer in its first incarnation. I had to decide what to keep and what to discard, and for that I was extremely grateful for the feedback of my excellent editor, Anjali Singh (who is now no longer an editor).

RR: Many beginning writers, who are anxious to rush their work into print, even to self-publish, don’t seem to realize how invaluable a good editor really is. How they can feel, almost instinctively, what works, what doesn’t, what needs to be expanded, what needs to be cut for various reasons like pacing, plotting…they’re thinking, “yeah interesting, even well written, but it’s a digression that detracts more than it adds to the arc of the story.” Or “why is she leading me away from the main story just when it’s getting interesting?” And “what does that scene have to do with anything, really? You could cut it and no one would even miss it!”

Painful, at first, for most writers to hear this, but after further consideration…you think, “yeah, maybe she has a point.” Or, “yeah, I never really liked that bit; don’t know why I left it in. Thanks for convincing me to finally get rid of it!”

I naturally assume people naturally assumed that you’re writing about your family. (I got that a lot from my stories, those with a Western character.) I’m assuming you’re not (based on comments from other interviews), though I’m assuming you can relate really well to these characters perhaps through extended families, friends, neighbors, people in general you’ve had contact with; they all seen believable, this family, their neighbors, as do the trial cases brought up. I was seeing Malaysia through their eyes, a different side than I was familiar with (mostly Malays in Penang and Perak). Did you catch any flack from anyone who insisted that you were writing about your family despite yourdenials? Any diplomatically way to handle that or did you just ignore them?

Preeta: Actually, the reverse turned out to be true, much to my surprise: people seemed not to recognise when they were written about. Either that or they were being extremely polite, ha-ha! Perhaps it would be more accurate to say: people chose not to come forward and confront me about the recognisable elements of their lives that had made it to the page. I think it helped that there is no character that is based on a single person from real life. They are, at most, amalgamations. In some cases I took incidents from one person’s life and made them happen to a character who is very obviously not based in any way upon that person. So no, I’ve had no awkwardness of that kind about my fiction, although I have had plenty of it in response to my nonfiction — but that’s another story. The short answer is that one doesn’t always get the chance to be diplomatic. Sometimes, if you write your truth, people are going to be angry. That’s just how it is.

RR: I know that anger. I once had five people convinced that I wrote about them in one of my stories about a woman having an affair with a married man in Penang. One woman was particularly upset since she thought I was writing about her husband (he shared the same name with the character, though he wasn’t Chinese). It started to get ugly until I was able to prove that I had written the story years before I had met them by showing them the original version from Her World. Needless to say, the wife (and the husband) were quite relieved….Then another woman I only knew professionally was adamant that I was writing about her! I wanted to ask, so which married man are you having an affair with here in Penang?

I was thinking, not so much your relatives (or friends) recognizing themselves, though I could see them being coy about it if it painted them in a bad light, but reviewers who assumed you were writing about your immediate family….In one of your interviews you spoke about how the chief criticism from America seems to be that your characters are unsympathetic, implying, in a way, that no one wants to read a novel about an unsympathetic character which, I believe, is pure nonsense. (Two agents made the same comment regarding the protagonist from one of my Penang novels after three chapters. The novel opens up at a low point in the protagonist’s life but he turns himself around and becomes a hero by saving all of these people’s lives.) Or is that just the American reading public? Did your agent/US publisher bring that up as a concern? (Hey, Preeta, can you make this family a little more likeable?)

Preeta: My thoughts about this have actually evolved immensely since Evening is the Whole Day was first published. I am in the process of trying to sell a second novel now, and I’ve come to believe that this kind of response — “your characters are unsympathetic” (which, actually, no editor has said about the second novel so far); “we can’t relate to these people”; “we can’t connect with these characters on an emotional level”; “we find this story/these people a little distancing/alienating” — is entirely culturally ordained and one hundred percent due to the fact that editors are white Americans and Brits (no, really — there are almost no editors of colour in the mainstream publishing industry) who themselves have white sensibilities and aesthetics (take, for example, the very criteria that decide whether a character is “sympathetic” or “unsympathetic,” or the question of how information is revealed between people — what is said, what is left unsaid. These are deeply cultural preferences.)

On top of this, these editors are catering first and foremost to a white readership. This is not the same thing as saying “people of colour don’t read,” obviously. I am saying that the white readership comes first for the industry, still, now, in 2017. When editors talk about “wider appeal” and “the audience,” this is what they mean, whether they know it or not. And when both editors and readers say things like “I found it hard to relate to these people,” what they really mean — though they don’t know they’re saying it — is “this culture makes me uncomfortable.”

Unfortunately, I don’t think there is a solution other than to radically diversify the gatekeepers of literary culture in the West. Until that happens, Anglophone writers who come from countries without their own extremely profitable, lively publishing industry (by which I mean India) are always going to have to choose between several awful options: 1) write for white people; 2) refuse to write for white people, therefore condemning yourself to an endless struggle with editors not to sacrifice everything you’ve written for your own people; 3) publish at home and give up the dream of a larger, more lucrative career (of course, there are lucky exceptions who’ve published at home and then had significant success abroad, but they are exceptions).

RR: I agree there tends to be a “white” or “Western” bias, maybe because they are the ones who are perceived to be buying the most books, having grown up in cultures that support the reading habit. Books in Malaysia are ridiculously expensive, a luxury that far too many Malaysians can’t afford, a real shame, something I’ve heard repeated over and over but nothing is done about it. Blame the booksellers, or the tariffs imposed on foreign books, but even the locally produced books for local writers are damn expensive….A huge example of that exception, of a writer writing in his home market, even in his native language, is Brazilian author Paulo Coelho publishing locally in Portuguese. It wasn’t until a fellow Brazilian living in the US offered to translate The Alchemist into English and was given permission to find a US publisher (in essence making him Coelho’s US agent) that his career took off. Books published here in Malaysia/Singapore rarely if ever break out onto the larger market. Like yourself, Shamini Flint published her popular Inspector Singh Investigatesseries overseas, proving it can be done, that a local writer can find a much larger audience at least for genre fiction which has a different market, of course, than literary fiction. Still it gives local writers hope. You guys, including Tash Aw and Tan Twan Eng, are paving the way…keep it up!

Contrary to some reviews, I didn’t see your novel as anyone’s particular story (any more than the other family members); I saw it as a composite of all of their stories as a dysfunctional family, whereby the whole is greater than the sum of its individual characters. You would weave into everyone’s mind, we would get their thoughts, their comments, their different perspectives as to what was going on even with the same scene while it was happening; you made the important moments so much bigger, which resonated with me because when I met US writer Bharati Mukherjee in Penang, she told me that I needed to do that, make the moment bigger at the end for my story “Sister’s Room” (about child prostitution). But it wasn’t until I read your book, that I thought, ah, this is what she meant. You had a masterful way of making your moments bigger by adding all of these different viewpoints so we got far more out of that scene than if it had been limited to one point of view. Was that something you had developed on your own or something you had picked up as part of your MFA program?

Preeta: I suppose I developed it on my own. I don’t see it as a very American aesthetic, and although it certainly wasn’t discouraged in my MFA program, it was uncommon in that program, and I suspect would have been uncommon in other MFA programs too. I think what you are talking about has first of all to do with the choice of an omniscient narrator. There is a higher power behind the novel, a voice with omniscience and a power of judgment that is almost divine. It’s that omniscience that drives the novel; that, in fact, tells us what to think about each character.

It’s interesting to think about that choice now because I made a very different one for the second novel — I made, in fact, the opposite choice, an unreliable narrator, a person who doesn’t even know everything there is to know about himself, let alone about others. But that omniscient voice I used in Evening is the Whole Day came from my lifelong love for Victorian novels. It’s a very 19th-century voice, and some people have actually argued that it fell out of fashion because humanity lost its faith in absolute omniscience.

I don’t know if that’s true, but I grew up reading Dickens and Tolstoy, Thomas Hardy, George Eliot; omniscience was my first literary diet, if you like. Virginia Woolf, of course, takes omniscience to a new level, and in some ways what she does should be the highest goal of every writer, if not every human being, to be able to slip into another person’s skin like that. It is the very definition of empathy. But I think the narrator of Evening is the Whole Day is modeled more on the bombastic, masculine omniscient narrators of those big 19th-century novels than on Woolf’s technique in To the Lighthouse. I’m not sure if I’ll ever write another novel in that exact voice, but the deep commitment to dissecting every character’s motivations is something that has stayed with me, and I think always will.

RR: Looking back at your MFA program in the US — the insights you gained from it and the connections that you made with other writers through the program — would you have done anything differently? Also, would you recommend a MFA program for young Malaysian writers (or any writer) just starting out, or do you think they could spend their limited income more wisely by just reading and writing a ton and finding their own natural voice (like Golda Mowe writing about Ibans in Sarawak)?

Preeta: If, on a limited income, you can manage to spend all your time reading and writing, then good for you! Then you could certainly do that. But I think it’s actually very difficult to find time to read and write as much as an aspiring writer should on a limited income. You will have a day job, and the reading and writing will both have to be squeezed in after work (when you will be tired) or at the weekends (when you will want to relax). It’s possible, of course; it’s certainly been done before. But it’s very, very difficult, and that’s where MFA programs save a lot of young writers. You should never attend an MFA program if you’re paying for it out of your own pocket.

But the best MFA programs basically pay you to read and write for two years. They buy you time, and that is an enormous, magical gift for an aspiring writer. It is the number one reason to attend a writing program: your actual job, for those two years, is to read and write. Of course, all the icing on the cake is lovely too: being part of a community that loves words above anything else, that thinks about language and storytelling constantly and rigorously; being able to talk about books and how they work (or don’t) all the time; having willing readers for your work for the rest of your life; getting to meet visiting writers, who are often among the world’s best living writers; learning about the business of publishing.

RR: That’s a great argument. I like what you said, “It is the number one reason to attend a writing program: your actual job, for those two years, is to read and write.” Incidentally, about meeting writers in Ann Arbor, I was in Borders in 1987 and met a guy who had just published an article that very week about meeting Jay McInerney (Bright Lights, Big City) at the same bookstore. A steady diet of that would be good for the writing soul.

The Writer, as do other writing publications, periodically runs a feature on the pros and cons of MFA programs; for me, a road not taken. I was on the road so much with Kinko’s managing and setting up stores (I set up ten in three states). I had to decide, become a partner, which was on the table, or buy myself time to read and write by moving to Malaysia. But it’s not the same by any means — a regret, too. You made the right decision. Hopefully, other Malaysian writers will be inspired to make that decision, too.

Did you feel there was any distinct differences on how your novel was received/reviewed locally (Malaysia/Singapore) versus US/UK? If it was published locally, they might dismiss it as inferior in some way, a general bias against local publishers, perhaps, as opposed to those like yourself being published overseas with well-known publishers.

Preeta: I wrote this novel (and I hope to write every novel) for Malaysians. I fought very hard not to sell out, not to have to change things for a Western audience, not to explain, not to compromise. And I did all that not to be difficult, but because I truly believe that it’s impossible to write equally for both audiences. Every step taken towards that Western audience is a step away from my own audience. The explaining is not anodyne: in that effort to alienate white people less, you do actually alienate Malaysians more. The explanations you put in for white people are distancing to your original intended audience. Nothing anyone ever says about being able to do both will ever change what I truly think about this. That said, I had decided to publish that book abroad. That wasn’t because I wanted money and fame and glory, but because I want the West to be reading about Malaysia, but more than that, I want them to be reading about us ‘on our terms.’ I want them to be reading the kinds of stories we tell about ourselves when no one is listening, except I want them to be listening.

RR: I like that, the way you put that: “the kinds of stories we tell about ourselves when no one is listening…” That was what I had felt while reading your novel, as if I were eavesdropping on various snide comments and asides not meant for my ears and saw this family in an unflattering, though, natural light. They were being as they are for no one else’s sake but their own.

Preeta: That, after all, is the purpose of literature: for all of us, including white people, to be reading about those who are not like us, and to discover even in that not-likeness a shared humanity that underlies everything. If we only read about people who are like us in the important ways — by which I mean that their skin colour may be different, but they still don’t ever make us uneasy; we still feel comfortable in their presence — then the existing balances of power will never be challenged by what we’re reading. I can’t get the West to listen if I don’t publish abroad, so I have to negotiate this minefield each time. Each time, I have to wonder afresh if I will be able to pull it off, if I’ll be able to refuse to address my work to white people, or to hold their hands as I gently guide them through my world, and yet get them to read me.

RR: It is a minefield, but it all comes down to the characters and story that demands to be told, demands to be read, not so much where the novel is set, but what resonates with the readers, what they can take away from it, what they can learn about themselves even from a totally different culture, for example, in a Nigerian-set story like Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart, which I recently re-read, whether you are white or nonwhite, whether you are Western or Asian, whether you have an interest in Africa or not...the story stays with you.

By the way, were Malaysians or the Indian community, receptive to you writing about the May 1969 riots? Hey, this is between the Malays and the Chinese, you Indians stay out of it! I was here during the October 1987 crackdown which prevented another racial riot — for months we could feel the pressure mounting all the way in Penang; then came the clampdown of the press and all those arrests under ISA. My ex-wife was a reporter for NST and they were given new strict guidelines what they could or could not report on — anything remotely racial was a huge no-no. We had close friends who wrote for The Star when it got shut down; a scary time, but nothing close to what happened in 1969!

Preeta: For the most part, yes, people were very receptive. Of course I’m not the first writer to cover May 13th in fiction; most famous, Lloyd Fernando wrote a whole novel about the riots. I can’t claim to have a clear idea of what readers in general thought of my treatment of May 13th, but the few who spoke to me about it were very positive, with one exception (but that person was Malay, not Indian). It’s interesting that you mention Operation Lalang, because the novel I’ve just finished deals with that incident.

RR: I must’ve been reading your mind. After hearing that you had been working on a second novel for a number of years, I’m glad to learn it’s finished. Does the long gap between your first novel and a second worry you as it often does many writers; this fear that, this may be it, that I’m a one-book writer. (Of course, there are tens of thousands of writers who have written a novel or even several but have yet to reach that one published novel stage — I know one gentleman who has nine unpublished novels fully written....Personally I would love to see a novel about Uma in America, heavily burdened with guilt knowing that despite Aasha’s assertion, she may have been the one to have killed Paati; guilt for Uncle Ballroom’s falling out with her father; guilt for allowing herself to be manipulated by her grandmother against her mother; guilt for abandoning Aasha…with plenty of flashbacks, further illuminating events that took place in the first book, plus her reaction when she learns of Chellam’s brutal death at the hands of her father…

Preeta: Yes, I finished the book earlier this year and it’s in the long process of (I hope) being sold. Of course the long gap worried me, even as I continued to slog through the writing; I worried I wouldn’t or couldn’t finish it, I worried everyone would have forgotten who I was by the time the second novel made it out (and perhaps they have!), I worried the second novel would be too different from the first, so that those few readers who ‘hadn’t’ forgotten me would be disappointed. But in the end you have to set those worries aside and keep working, or risk devoting your life to worrying instead of writing. In response to your speculation, I do have to say: this novel is not a sequel to Evening is the Whole Day. It isn’t about an Indian family; it is different in possibly every way (style, structure, tone, voice, point of view as I previously mentioned).

RR: Perhaps in the future, after enough time has passed, you’ll consider the idea….Just curious, do you prefer being called a novelist, an author, or a writer? Since we’re on the subject of identify, after having lived overseas so long, do you consider yourself as an expat writer, or a Malaysian writer, or part of the larger India Diaspora of writers? Why?

Preeta: I can’t say that I have any strong preference! I refer to myself as a writer, because I also write short stories and essays. But I’m not offended or annoyed to find myself referred to as a novelist or an author by others. As for identity: I consider myself a Malaysian writer. I realise that my living overseas means some people will contest this identity, arguing that I can’t be an “authentic” Malaysian writer if I haven’t lived in Malaysia for a quarter of a century. But Malaysia continues to be the only place I write about and the only place I want to write about in my fiction. To me, living overseas makes it easier for me to see and to articulate some things about the country that I don’t think I’d be able to if I were living there. I’m speaking only for myself here, and not claiming that Malaysian writers who live in Malaysia are less able to see what I see or write what I write. I only mean that for me, personally, distance is crucial. As for the Indian Diaspora question: I admire many Indian writers, but I don’t consider myself one of them because Malaysian culture is distinct from Indian culture on the subcontinent; South Asia and Southeast Asia are two quite different regions.

RR: Distancing is a way that allows you to see things up close….I keep finding myself writing about America even though with each passing year as an expat I know it less and less, but it is still home; it is where I am from; it is what I am still trying to make sense of even more so in this age of Trump with its disturbing undercurrent of half truths, blatant lies and white supremacy.