Robert Raymer's Blog, page 3

November 23, 2019

A Walk with My Two-Year-Old Son

I first posted this in February 2007 in another blog, though the actual walk took place in 2006. Based on the original comments, I regret not bringing a camera. Nor did my phone, an old Nokia, have one either.

Before moving to Sarawak and to get out of rut, I decided to take my two-year-old son, Jason, for a walk. Usually when we walk it’s to a known destination for a known reason—running errands for me or playing outside with him. Today would be different. I wanted to see if we could learn anything in half an hour. Any longer than that, the mosquitoes would be biting.

We lived in Penang, in a mostly Chinese residential area, in Malaysia. Other than being Jason’s father, I teach creative writing and recently published a collection of short stories set in Malaysia, Lovers and Strangers Revisited—the Silverfish version.

Lately I’ve been feeling weary of the “author” bit and needed to get back to “writing”. But in order to write, I needed to start observing my surroundings again like I used to do when I first moved from America to Malaysia. Jason, on the other hand, like most two-year olds, is a natural sponge, taking everything in around him. He’s also tiny for his age, petite like his mother, a Bidayuh from Sarawak.

I grabbed some biscuits for the both of us and a spongy orange ball to play with. We didn’t get far; halfway down the stairs, I realized I had left the ball behind while unlocking the door.

“Back so soon?” my wife asked, teasing me.

Jason wanted to hold the ball but I didn’t want him to drop it into the monsoon drain that ran alongside our street, so I handed him a biscuit instead and held his free hand securely. I didn’t want him to fall into the drain either.

We turned the corner to the small field behind our building; we were both startled to see an elderly Chinese man sitting on the ground, looking suspicious and looking suspiciously at us. Careful not to make any eye contact, I steered Jason around this man, whom I had never seen before. Not far away from him, on the other side of a tree, was a small wicker basket. Normally, I would have taken a closer look but the man’s gaze continued to bear down on us, so we kept walking.

Initially I planned to play ball here, but my wife had warned me before about getting my son’s hands dirty and having him put those dirty fingers into his mouth. So, I handed Jason another biscuit. I figured we’d finish the biscuits first and play ball later. We were half way to the end of the field, when the Chinese man began to point and shout at us as if ordering us off the field. I detoured toward the road, but then I saw it, a zebra-striped dove resting peacefully in the center of the field.

I pointed it out to Jason, and his eyes grew with excitement. We ventured closer. The Chinese man shouted and furiously waved us away. Since he was making his way toward us, wicker basket in hand, I thought it best to lead Jason toward the side of the road. We stood there eating our biscuits, observing both this strange man and this bird. I thought perhaps he was a bird-catcher, like Papageno in The Magic Flute. (I had written a novel about a delusional man obsessed with The Magic Flute.) The man cautiously approached the dove. He set the basket down, opened the lower portion and gently coaxed the dove inside.

Afterwards, he began to pick at the grass. At first, I thought he was gathering some edible goodies for the bird. Then I saw a small spool. He was rewinding the line that kept the bird from fleeing. I assumed the wings had been clipped to prevent it from flying away. This dove—called a peaceful dove, I later learned—was popular for cage-bird singing competitions. The man carried the dove in the basket under his arm to his motorcycle; as he rode off, Jason and I waved goodbye.

We made our way up a short alley, crossed the road and walked along a road I had never been on before since I had assumed it was a dead end. Jason and I discovered a much bigger field containing an old playground.

Delighted, Jason practically dragged me to the nearest sliding board. I helped him up the steps and sat him down at the top of the plastic slide. He squealed with delight when I caught him at the bottom—his first slide! He slid down three more times before I led him to a larger sliding board and placed him at the bottom and rolled the ball down from the top. He laughed and caught the ball.

Catching on to this new game, he threw the ball about halfway up the slide and laughed as the ball rolled down to him. He could’ve played all night, but I spotted an even larger slide at the far end of the field, so we went to investigate. It was an old wooden slide and way too tall for Jason or me. Again, I placed him at the bottom of the board and rolled the ball to the top. Jason’s eyes grew wide and wider as the ball rolled toward him, gathering speed along the way.

Next up was the adjacent swing. Leaving the ball on the ground, we got on with Jason on my lap. He giggled as we swung, higher and higher. Wanting his ball, Jason got off to play with it while I continued to swing. Jason suddenly ran behind me. I desperately tried to stop the swing from slamming into him. I somehow managed to reach around and catch Jason by the shoulder and stopped him, the swing an inch from his head.

Relieved but upset, I had a stern talk with Jason about running in back of swings. Jason, nodded. He may not have understood my every word but he understood my mood and knew that he had done something wrong; he also knew or sensed it wouldn’t be fair to punish him because I was partly at fault. Either way, we agreed not to tell his mother.

Noticing a mosquito on his arm, I swatted it away and we made our way back across the field. Blocking our exit, however, were four large stray dogs. Being a dog lover, Jason pointed with glee and said, “Dog!” He would’ve run straight toward them if I hadn’t held him back. Not sure if the dogs were friends or foes, I maintained a wary eye, while the four dogs eyed me and Jason rather warily. Afraid he might hug them to death, the dogs wisely moved from our path. Jason waved to the dogs as we passed by and said, “Bye!”

Jason and I crossed the road where I noticed three Indian children playing in a fenced in area with three rabbits. Jason didn’t know what to make of the rabbits. Other than Bugs Bunny, he had never seen a live rabbit before. Eyes large and round, he marvelled as the rabbits hopped across the lawn pursued by the three children.

Watching us watch the rabbits were two stray cats. Jason took an interest in them. He gave chase and the cats, fearing for their lives, hid under a car. Jason squatted down, bent over, and laughed as if to say, “You can’t hide from me!”

Four dogs, three rabbits, two cats. What next? We were nearly home when we came upon this woman who was walking beside us, almost step by step, although we were in the alley and she was at a lower level beside her building. The woman kept looking up at Jason and me as if trying to get our attention. Then we saw it. Perched on her left hand was a small green bird. I pointed it out to Jason. Like the elderly Chinese man, the woman was taking her bird for a walk.

When we reached home, I glanced at the time. Exactly half an hour had passed since we had left for our walk. In that short time Jason and I had seen a lot and had a whole lot of fun and even made a discovery and learned a valuable lesson about safety.

Already I was looking forward to our next walk—no doubt our first walk in Sarawak. Soon, though, he would have a little brother to walk beside him.

--Borneo Expat Writer

Published on November 23, 2019 02:55

August 24, 2019

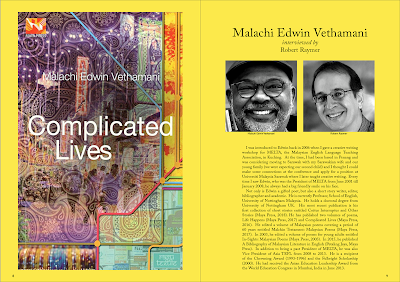

My interview with Malachi Edwin Vethamani is in Blue Lotus 19

My interview with poet and short story writer Malachi Edwin Vethamani, author of Complicated Lives and Life Happens was published in Martin Bradley's Blue Lotus 19, pages 8-17. Originally I had blogged about our interview in July 2019

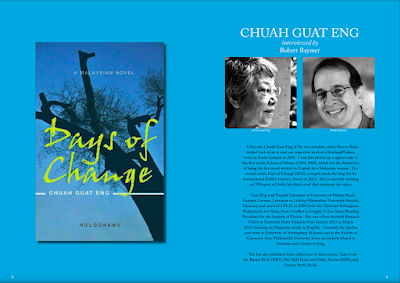

My other interviews with Preeta Samarasan, author of Evening is the Whole Day, was published in Blue Lotus 12, Ivy Ngeow, Cry of the Flying Rhino, in Blue Lotus 13 and Golda Mowe, author of Iban Dream and Iban Journey, in Blue Lotus 15 and Chauh Guat Eng author of Echoes of Silence and Days of Change in Blue Lotus 16

Blog links to the other interviews with four Malaysian novelists:

Ivy Ngeow author of Cry of the Flying Rhino, winner of the 2016 Proverse Prize.

Golda Mowe author of Iban Dream and Iban Journey.

Preeta Samarasan author of Evening is the Whole Day.

Chauh Guat Eng author of Echoes of Silence and Days of Change.

Five part Maugham and Me series

Joseph Conrad and Me —Borneo Expat Writer

Published on August 24, 2019 22:34

July 24, 2019

Arte: Joseph Conrad and Me—Sarawak’s French Connection to Lord Jim

Pierre Duyckaerts and Sebastien Bardos

Pierre Duyckaerts and Sebastien Bardos“The mysterious East faced me, perfumed like a flower, silent like death, dark like a grave,” wrote Joseph Conrad, the Polish-born English novelist of Heart of Darkness, Almayer’s Folly, and An Outcast of the Islands. When French documentary maker Sebastien Bardos of Elephant Doc contacted me in late March about his project “Conrad’s Malaysia” he asked me a question. Of course, Conrad had been to Borneo where he had set several of his novels, but the question posed to me, had he ever been to Sarawak? The short answer is no, but the long answer is, without Sarawak, Lord Jim would never have been written.

Sebastien works with Laure Michel, who came to Sarawak in 2017 for a Somerset Maugham and Sarawak pepper documentaries, which I had blogged about in the five-part series “Somerset Maugham and Me.” Like Maugham, Conrad will be filmed for the Franco-German Cultural Channel Arte for the program “The Invitation to Travel” or L’Invitation au Voyage to be aired in October 2019.

Sebastien will be working with Karen Shepherd, who had worked with Laure on the pepper documentary and her husband Peter John, featured in the segment “A Personal Invitation”. On the previous production, Karen and I worked closely with Laure, recommending people and sites. We did the same with Sebastien until he hired fixer Edgar Ong, who for thirty years had worked in the local filming industry including such notable films as Farewell to the King (1989) with Nick Nolte and The Sleeping Dictionary (2003) with Jessica Alba, both set in Sarawak.

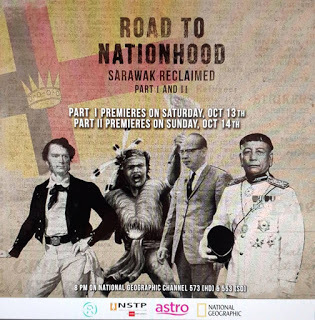

Edgar would partner with Adrian Cornelius who scouts locations and deals with logistics. Adrian is also involved with the on-again-off-again film The White Rajah, about the life of James Brooke, that dates back eighty years to the mid-1930’s when Errol Flynn was originally scheduled to star, until delays and World War Two came along. I met Adrian last year with Rob Nevis while discussing taking part in The Road to Nationhood series. Initially I was considered for a non-speaking role of Charles Brooke but ended up playing smaller roles, including a man who was beheaded (sadly cut from the documentary) and Captain Henry Keppel—who, as it turned out, gave Joseph Conrad a helping hand in writing Lord Jim. More about that later.

Edgar had called for a meeting in May to work out some preliminary details and suggestions for locations (I had suggested Fort Margherita for my segment), but the day that we had agreed upon proved problematic for me. My Bidayuh mother-in-law had passed away and that was the day of her funeral.

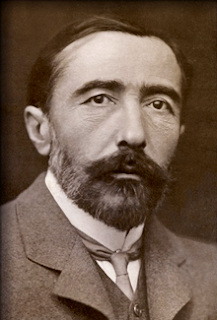

Getting reacquainted with Joseph Conrad, I reread Almayer’s Follyand Lord Jim and delved into the thorny issue of his connection to Sarawak. Born in 1857 at the height of the British Empire, Joseph Conrad started writing late, in his thirties, after twenty years in the merchant marines, four with the French and sixteen with the British. Conrad always viewed himself as a writer who sailed, rather than a sailor who wrote, and used the pen name Joseph Conrad for his first novel, Almayer’s Folly, set on the coast of Borneo. Almayer’s Folly, together with its successor An Outcast of the Islands, laid the foundation for Conrad’s reputation as a romantic teller of exotic tales, a label he disliked; he felt it was a misunderstanding of his purpose and it would frustrate him over his career.

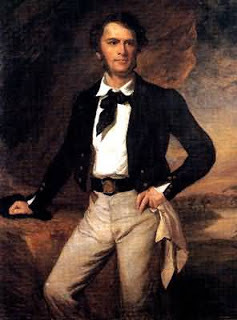

Although Conrad had never been to Sarawak, he did have three significant connections to Sarawak that greatly aided his writing of Lord Jim. Published in 1900, Lord Jim was famously based, at least the second half of the book, on James Brooke, the first White Raja of Sarawak. An English adventurer, Brooke sailed into Borneo in 1938 and earned the title White Raja after assisting Pangeran Muda Hashim of Brunei in defeating the rebels led by Datu Patinggi Ali.

The first half of Lord Jim, however, deals with the Patna incident, whereby the captain, the first mate (Lord Jim) and two crew members abandoned what they thought was a sinking ship leaving hundreds of passengers to their own fate. This episode was based on an actual event. In 1880, the S.S. Jeddah travelled to Singapore to Penang en route to Jeddah and began to take on water during a tropical storm; the captain and some crew abandoned ship with 700 passengers aboard. The ship didn’t sink, so there was a huge outcry and a trial in Singapore over their cowardly actions.

Coincidently, James Brooke had an Official Inquiry in Singapore over misleading the British about killing so-called pirates to collect bounty, when in fact he was fighting natives defending their land. Like the character Lord Jim, James Brooke had been living under a cloud.

Resisting British imperialism, Brooke founded his own dynasty, the White Rajas that ruled a jungle kingdom larger than England for one hundred years. James Brooke became a cause celebrity, often written about in Illustrated London News, which was founded in 1842, coinciding with the start of Brooke’s ‘war’ against the so-called pirates. Brooke was mythicized as an Imperial Hero, capturing the imagination of would-be romantics and adventurers. In addition to being the model for Lord Jim, James Brooke was the inspiration for Rudyard Kipling’s “The Man Who Would Be King”. Conrad was hailed as ‘the Kipling of the Malay Archipelago’.

On 6 July, I arrived at The Ranee Boutique Suites at the Waterfront where Edgar Ong introduced me to Sebastien Bardos and Pierre Duyckaerts, who had flown in from Penang on about two hours sleep. They found the heat in Penang oppressive and had been sweating nonstop. I didn’t have the heart to tell them that Kuching might be worse because of the humidity; luckily for them, it was partly cloudy outside. Sebastien told me that for the Conrad story they had previously interviewed Jean-Luc Henriot in Singapore, Serge Jardin in Kuala Lumpur, and in Penang, Gareth Richards, who runs the Gerakbudaya bookstore. Serge Jardin, who I believe I met in Penang many years ago, lives in Malacca and took part in the Somerset Maugham documentary. Sebastien informed me that my book Trois autres Malaisie, the French translation of Lovers and Strangers Revisited , was being listed in French travel guidebooks to Malaysia, good news for my French publisher, Editions GOPE.

Over coffee and tea, Edgar ran through the shooting schedule for the next three days. Before leaving the hotel, Pierre hooked me up with a microphone. The plan was for Adrian to drive us across the Sarawak River to Fort Margherita, but I suggested it would be better for Sebastien and Pierre to take a tambang across, which I thought would be more interesting and quicker than a roundabout drive and risk getting stuck in traffic. Adrian could meet us at Fort Margherita.

Sebastien and Pierre were expecting a bigger boat, perhaps like the one the tourists use for the Sarawak River Cruise, so they seemed taken aback when I pointed out the tambang waiting for us. We ducked our heads and climbed aboard. I sat up front looking out at the river while Pierre filmed me taking in the view and also the steersman, while trying to catch the splashing sounds made by the tambang. Once we reached the other side, they filmed me climbing out onto the small jetty where a few passengers were waiting to board. Unfortunately they had to wait a little longer since Pierre wanted to film the steersman in front of the tambang. The waiting passengers watched with amusement.

After filming the tambang departing the jetty, Pierre filmed another arriving with Kuching as a backdrop. He took more shots of the Waterfront and then filmed me standing at the edge of the jetty. I was told to keep my lower body planted (and to avoid falling into the river behind me); however, I could move my upper body as I talked about Joseph Conrad, who died in 1924, on the 3rd of August, which happens to be my birthday. Sebastien and Pierre wore hats while I melted in the late-morning, partly cloudy sun. Thankfully, Sebastien had an umbrella, which provided us shade in between shots.

In addition to Conrad and his connection to James Brooke, I was asked to speak a little about Kuching—its history, its reputation as a river city, the Waterfront and the antique galleries at the Main Bazaar, as well as my own impressions when I first visited Kuching twenty years ago. I purposely did not talk about the ubiquitous cat statues; Kuching means cat in Malay.

We took a short hike up to Fort Margherita and found Adrian who offered us lime-flavored 100Plus isotonic drinks, their first. Pierre then filmed me with the fort behind me in the distance as we continued with the interview. Fort Margherita was named after the Second White Raja’s wife, Ranee Margaret Brooke, author of My Life in Sarawak. I pointed out another, though minor Sarawak connection, when Conrad wrote a letter to the Ranee, praising her Uncle, James Brooke.

“The first Rajah Brooke has been one of my boyish admirations, a feeling I have kept to this day strengthened by the better understanding of the greatness of his character and the unstained rectitude of his purpose. The book that has found favour in your eyes has been inspired in a great measure by the history of the first Rajah’s enterprise and even by the lecture of his journals as partly reproduced by Captain Mundy and others.”

Conrad knew the Malay Archipelago as a sailor. In writing Lord Jim and other Borneo-based novels, he could rely on his own observations for the natural surroundings and the sea. His landfalls, however, were limited to four stops at Berau in East Kalimantan, which he used as a setting for Almayer’s Folly. Instead, he relied on reading first-hand accounts by others including James Brooke’s journals and those who had written about him, as mentioned in the above letter. He also relied heavily on a second major connection to Sarawak, Alfred Russel Wallace, of the Wallace Line fame, who was based in Sarawak for fourteen months, collecting birds and beetles and other specimens to ship back to England.

Wallace travelled extensively throughout the region and wrote about his experience in The Malay Archipelago (1869), highly regarded as a great travel book and the most famous book on the Malay Archipelago—the very reason Conrad kept the book handy at his bedside, which he had used for several novels. Conrad not only relied on Wallace’s description of the area but also used Wallace himself as a model for the character Stein in Lord Jim. Stein was the man whom Marlowe had convinced to hire Lord Jim to work for him in some remote, out-of-the-way locale…so he was sent to Patusan, a third connection to Sarawak.

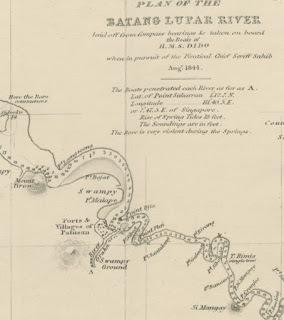

Some experts have argued that Patusan, the setting used in Lord Jim, was based on Berau in East Kalimantan, a place Conrad had visited. Others suggested that Patusan was located in Java; however, convincing arguments have been made that Patusan was in fact based on an actual site on the Batang Lupar river in Sarawak that was called—Patusan. Although Conrad was never there, he did read about Patusan in a book by Captain Henry Keppel. A friend of James Brooke, Keppel wrote about their exploits in Borneo in The Expedition to Borneo on HMS Dido for the Suppression of the Pirates—another significant tie to Sarawak.

More importantly, inside of Keppel’s book was an actual map of Patusan, identifying the fort and village that Conrad had put to good use since he had never been there himself. By looking at the map, you could see that Conradfollowed it closely in his descriptions of the fort and the village, the river, the tributaries—integral to the ending of Lord Jim. That map, along with Keppel’s descriptions of Patusan, was perfect for Conrad to use in Lord Jim—in lieu of actually visiting the location—just as Conrad had based the Patna incident on the real S.S. Jeddah and the subsequent trial in Singapore.

Incidentally, although Joseph Conrad never visited Sarawak or Patusan, present day Sri Aman, another famous English writer did—Somerset Maugham. Maugham, in fact, nearly died in Patusan in the 1920’s in a tidal bore and wrote a story about the incident, “Yellow Streak.”

When I finished speaking, we went to another side of Fort Margherita so Pierre could take some more shots. He then brought out a drone and I couldn’t help but recall what happened to the drone used in other French documentary; it went around a bend and struck an overhanging branch and was lost in the river. Pierre used the drone to film me walking alongside Fort Margherita; then walking down some steps and approaching the entrance.

Later, after enough footage had been taken outside of Fort Margherita (after Sebastien and I had finished solving the world’s problems), Pierre packed the drone away and we entered the Fort. Pressed for time, we had to bypass the nicely done Brooke Gallery@FortMargherita. They filmed me inside the fort climbing the stairs and making my way along the parapet walk on two sides, past a bolted but unlocked door containing some heads. I had first seen the human heads about twenty years ago, which they kept in a suspended rattan basket, but now covered with traditional cloth to keep tourists from disturbing them. Previously I had blogged about seeing heads at a Bidayuh longhouse and being disturbed that evening at my wife’s village by an actual spirit—my first and hopefully my last encounter.

by Paul Carling

by Paul Carling

by Paul Carling

by Paul CarlingI kept asking Sebastien if they wanted me to open the door to have a peek inside but they didn’t seem to understand the significance, so I would glance at the door each time I passed by, only natural since there was a skull painted on the door. Sebastien did press me about my views of howthe Bidayuh revered James Brooke because he had put an end to their seemingly endless slaughter by the Iban head-hunters. Back in the 1840’s, village after village, including my wife’s village, Quop, had been decimated.

At a lookout tower, they filmed me gazing out at the Sarawak River, slowly turning my head from right to left. Back on the parapet walk, despite the mid-afternoon sun beating down on me, the clouds having long since departed, we continued with the interview. I talked about the tragic fates that Conrad gave to the principle characters of his novels and stories. He often saw the darker side of man whether it was The Heart of Darkness in the Belgian Congo, The Secret Agent, or the elusive anti-hero of Lord Jim, trying to escape the shame of abandoning the Patna, while still remaining noble—not an easy task for any man to do. This was also the theme of Lord Jim, the restoration of a man’s honor and pride. In many ways the character Lord Jim is one of us…tragic; a part of him would always be kept secret so we would never know like others will never know our own secrets.

view of Old Courthouse with Cat

view of Old Courthouse with Cat Stockade

Stockade Astana

AstanaAfter wrapping up the filming at Fort Margherita, we dropped off Pierre at the hotel so he could take some shots of the nearby historical building since there was still sun. Adrian then took Sebastien and me to the Old Courthouse where we met with Karen Shepherd, who would be talking more in depth about Alfred Russel Wallace, and Peter John, about the local inhabitants.

Edgar Ong joined us. Sebastien and the others tried to finalize the details and the logistics for the next two days of filming in Kuching. They had just settled on an itinerary—Santubong for one day and Bau, Siniawan and the river along Suba Buan for the other day—when Sebastien asked about seeing some wildlife, particularly the proboscis monkeys or the orangutans, to work into the documentary. Since they couldn’t do both (located in opposite directions) and still complete the other filming in Bau, they settled on Bako National Park where they could see plenty of wildlife in addition to the proboscis monkeys and some jungle shoots for Karen.

Proboscis monkey, Sarawak Tourism

Proboscis monkey, Sarawak TourismSince my part of the Joseph Conrad filming had come to an end, I called it a day, feeling rather burnt out from way too much sun, yet feeling satisfied in knowing that without Sarawak, Joseph Conrad would never have written Lord Jim.

—BorneoExpatWriter

Somerset Maugham and Me—Part I-V

Beheaded on the Road to Nationhood—Part I

Beheaded on the Road to Nationhood—Part II

Published on July 24, 2019 02:21

July 18, 2019

INTERVIEW MALACHI EDWIN VETHAMANI: Robert Raymer chats with Malaysian Writer Malachi Edwin Vethamani on Writing and Publishing his Books

I was introduced to Edwin back in 2006 when I gave a creative writing workshop for MELTA, the Malaysian English Language Teaching Association, in Kuching. At the time, I had been based in Penang and was considering moving to Sarawak with my Sarawakian wife and our young family (we were expecting our second child) and I thought I could make some connections at the conference and apply for a position at Universiti Malaysia Sarawak where I later taught creative writing. Every time I saw Edwin, who was the President of MELTA from June 2001 till January 2008, he always had a big friendly smile on his face.

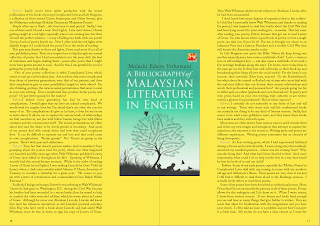

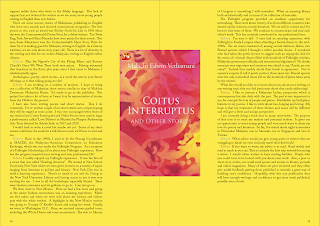

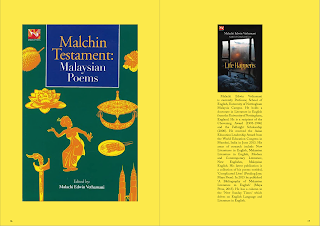

Not only is Edwin a gifted poet, but also a short story writer, editor, bibliographer and academic. He is currently Professor, School of English, University of Nottingham Malaysia. He holds a doctoral degree from University of Nottingham UK. His most recent publication is his first collection of short stories entitled Coitus Interruptus and Other Stories (Maya Press, 2018). He has published two volumes of poems, Life Happens (Maya Press, 2017) and Complicated Lives (Maya Press, 2016). He edited a volume of Malaysian poems covering a period of 60 years entitled Malchin Testament: Malaysian Poems (Maya Press, 2017). In 2003, he edited a volume of poems for young adults entitled In-Sights: Malaysian Poems (Maya Press, 2003). In 2015, he published A Bibliography of Malaysian Literature in English (Petaling Jaya, Maya Press). In addition to being a past President of MELTA, he was also Vice President of Asia TEFL from 2008 to 2013. He is a recipient of the Chevening Award (1993-1996) and the Fulbright Scholarship (2000). He had received the Asian Education Leadership Award from the World Education Congress in Mumbai, India in June 2013.

RR: Lately you’ve been rather productive with the recent publications of two books of poetry, Complicated Lives and Life Happens, a collection of short stories Coitus Interruptus and Other Stories, plus the Malaysian anthology Malchin Testament: Malaysian Poems!

People often say or think…who has time to read poetry? Sadly, I was one of them until I found a way! Red Lights. Like most drivers I detest getting caught at a red light, especially when I am running late, but then I found the perfect solution — a way of killing two birds with one poem! I keep a book of poetry beside me. Now I often wish the red lights were slightly longer so I could finish the poem I’m in the midst of reading.

This past year, thanks to those red lights, I have read most if not all of your published poetry. They even inspired me to dig through my unread collection of poetry that I had accumulated over the years with the best of intentions and began reading them…poem after poem that I might never have gotten around to read. And for this, I am grateful for you for getting the poetry ball rolling. One of your poetry collections is titled Complicated Lives, which seems to sum up our lives these days. Are our lives truly more complicated than those of previous generations, even that of our parents, and does that complication give us more possibilities (angst) to write about? I’m also thinking, perhaps, the various sexual permutations that seem to exist in your own writing. Does complicated lives produce better poetry and prose? Or just better gossip for the readers?

Edwin: I believe every generation has had its own kind of complications. I would agree that our lives are indeed complicated. We would wish for simpler lives but I’m afraid that’s not often the case for many of us. The complications do give us (at least, it does for me) more to write about. It allows me to explore the various kinds of relationships we find ourselves in, not just with fellow human beings but with fellow creatures and the environment itself. The sexual permutations are often about love and the desire to be loved; gender is secondary. And some of my poems deal with sexual desire and how that could complicate lives. It can be difficult to separate sex and love and that could cause its own complications. “Better gossip?” No! There’s no gossip in the poems. There’s both pain and celebration.

RR: True, but that doesn’t prevent readers (and nonreaders) from gossiping about the poems (and the poet), which was what happened one hundred and fifty years ago when Walt Whitman published Leaves of Grass (and added to it throughout his life). Speaking of Whitman, I recently had this surreal literary moment. While in the midst of reading Leaves of Grass (at red lights), I was reading Lincoln by Gore Vidal (at home), when a clerk-cum-novelist asked Salmon P. Chase, Secretary of Treasury, to consider a clerkship for a great poet. “He comes to you, sir, with a letter of introduction and commendation from Ralph Waldo Emerson.”

Suddenly I had goose bumps; I knew he was referring to Walt Whitman! I knew he had gone to Washington D.C. during the Civil War because his brother had been wounded in a recent battle; then he stayed to help to comfort the other wounded soldiers, which he wrote about in Leaves of Grass. Although he never met Abraham Lincoln, Lincoln did know him (and his infamous reputation) as did Lincoln’s personal secretary, John Hay who later wrote a book about Lincoln and had asked Walt Whitman, since he was in town, to sign his copy of Leaves of Grass. Then Walt Whitman added several tributes to Abraham Lincoln after he had been assassinated. I don’t know how many degrees of separation that is, but suddenly I felt like I personally knew Walt Whitman; and thanks to reading his poetry, I was inspired to read four books about the Civil War that had been lying around for years waiting for…someday. That day came after reading your poetry, Edwin, because that got me to read Leaves of Grass. So, who knows where a good book of poetry or even a single poem can take you if you let it? For me, it brought me closer to an infamous Poet and a famous President and a terrible Civil War that still haunts the American psyche today.

In Life Happens you quote the Bible “Above all, keep loving one another earnestly, since love covers a multitude of sin”. Love — wanton love or self-indulgent love — can also causea multitude of sin (and a few marriage breakups along the way). Do lovers, more today, than in the past, go too far in their kiss-and-tell books or their hook-up and broadcasting their blogs all over the social media? For the lover, it can increase their notoriety (Don Juan, anyone? Or the Kardashians?), but what about the named or flushed-out victims who must deal with the real-time fallout that can destroy their current relationships and wreck their professional and personal lives? Are people going too far to inflict pain on others (payback) and even themselves? Is poetry and even prose, based on your own writing, truly cathartic or are writers merely a glutton for punishment? But at whose expense?

Edwin: I certainly do not subscribe to any form of kiss and tell in my writing. Those who write such real-life confessional books are certainly not doing it for any kind of literary reasons. Sadly, that seems to be what some publishers want, and they know these books have readers and they will sell copies.

My poems are often drawn from various sources and I rework them and create my own images and metaphors that attempt to capture the experience, the moment or the emotion. Writing prose and poetry are different experiences. Writing poetry sometimes has an element of being therapeutic.

RR: As does writing prose, which I had experienced firsthand during a divorce and a custody battle. I wrote a long story that suddenly answered my unasked question…where was she coming from? Why was she doing this? And what had I done that led to this? And, more importantly, what could I do to help resolve this in a way that would be best for both of us and our child? Edwin: Some of my early poems, especially the ‘Mother Poems’ in Complicated Lives deal with my coming to terms with my mother’s old age and Alzheimer’s illness. These poems are very close to me and I still find it difficult to read them aloud in the Readings sessions. I actually invite others to read these poems.

Some of my poems have been described as confessional poems. Here, I’d say that I’m not necessarily the persona in all of these poems. Poetry allows for this ambiguity and I do draw on it. When I write stories, I draw from various sources. If one listens and looks hard enough you see and hear so many things that give fodder to writers. They are seeds that allow for fertilization with the imagination and you have your stories. I often take an issue or a problem and see how I can give it a fresh look. My stories do not have a clear closure as I want the readers to continue to think about the characters and what options they may have.

RR: We write, if not for ourselves, then for others, it seems to me, even if it is only for one person. What may be closure for the writer and closure for the reader may be very, very different. It’s how we react or respond to a particular piece of writing or, by association, how it links to our past that suddenly awakens us or even provides a solution that we hadn’t been seeking. Each reader may respond to a different aspect of the story or the poem, even to a particular word that resonates for them in unexpected ways. Thus, the cause and the effect can go on and on for generations of readers…long after the author had passed away.

Another of your quotes from the same collection is TS Eliot, “Only those who will risk going too far can possibly find out how far one can go.” This is a true sentiment that applies to various aspects of our lives, including running a marathon, but specific to writing, based on your own experiences, please elaborate.

Edwin: I subscribe to what Eliot is advocating in this quote. I like to think that my writing is an attempt at “going too far”. One needs to be careful with what one decides to publish. There are things I write and don’t publish. But I certainly needed to write them for myself. My editor is my barometer who cautions me, and I rarely disagree with him. Some of my readers say I’m brave to publish what they read in my books. So maybe, now I can go a little further. Malaysians self-censor for many reasons. There is the fear that our work might be banned or at worse the writer gets arrested. One has to be careful with matters of race and religion. My writings do deal with race and aspects of religion, but I am very careful not to offend though I might touch on these issues.

RR: I remember reading one young poet in an anthology that I was asked to write a comment for and it seemed to me that was exactly what he was trying to do, offend. My advice to tone it down fell on deaf ears; I had told him, later, when you mature, you are going to cringe and regret this.

What got you interested in reading and writing poetry? Who were your early Malaysian influences or mentors at school? Which poets, both local and overseas, grabbed you or shook you out of your complacency and made you think, this is what I want to do!

Edwin: From an early age, I loved reading. A habit I picked up from my eldest brother. As we could not afford to buy books, I joined the British Council library and the library at the Lincoln’s Cultural Centre. Living in Brickfields in the 60s and studying in Methodist Boys’ Secondary School, Kuala Lumpur, I could walk to both the libraries. I used to look for new books and try to be the first reader.

In my 20s, I read more poetry than prose. And I read more modern poetry than I did the Romantics like Wordsworth. In fact, I only began to like Wordsworth much later in life. I enjoyed T.S. Eliot from my Form 6 days. I loved the way he wrote about people and life after World War Two. His religious poems resonated well with me, coming from a Christian background. I try to capture our contemporary society in my poems too.

As in the case of poetry, I read more modern prose writers like Virginia Woolf, Joseph Conrad and E. M. Forster. Shakespeare grew on me very quickly too. I started reading Shakespeare in Form 4. I had a wonderful English Literature teacher. She introduced me to many writers including Ovid. The American writers came much later in my life, then I discovered Walt Whitman, Emily Dickinson, Hemmingway, Steinbeck, Faulkner and Baldwin and Scott Fitzgerald.

Among the earliest Malaysian writers, I read were Ee Tiang Hong, Muhammad Haji Salleh, Wong Phui Nam and Hilary Tham. Edwin Thumboo had just brought out a volume of Malaysian and Singaporean poems entitled ‘The Second Tongue’ and it opened the door to local writing, especially poetry. I read Malaysian short stories and novels much later.

I had the privilege of being a student of Professor Lloyd Fernando. He was certainly a mentor and role model. We became friends and he gave me access to his personal library in his home and much of my early research on the bibliography of Malaysian literature was done here.

RR: Getting the right teacher or lecturer can make a huge difference; one turns you on, the other shuts you down. For your Malaysian anthology Malchin Testament: Malaysian Poems, which spans sixty years and covers nearly sixty poets, what were your criteria for choosing the poems? I could imagine that would have been a difficult undertaking, not wanting to leave someone deserving out, against cries of bias or showing favouritism or having to defend yourself to the inevitable backlash from fellow poets and friends, “How come so-and-so has four poems and I only have three!”

Edwin: I had several criteria for selecting the poems. First, that the poets are Malaysians or are poets born in Malaysia and may now have gone abroad but continue to write about Malaysia. Second, I chose only poems that have been previously published.

My work on The Bibliography of Malaysian Literature in English helped me to find just about every published poetry collection by Malaysians poets. Third, I only published poems that the writers gave me permission to publish as they hold the copyrights to the poems. The number of poems for each poet represented the volume of the poet’s publications. There are some poets with just one or two poems. These are usually the emerging poets whose works have appeared in anthologies and the poets did not have their own collection of poems. There are more poems from the established Malaysian poets.

RR: That sounds fair; I hope they were all happy! I liked how the anthology, as you stated, “brings together voices of poets from multicultural and multilingual Malaysian appropriating the English language for their own expression” which I feel is a tribute for all Malaysians, something everyone should be proud of. But has there been a struggle for this multicultural and multilingual Malaysian voices to be heard and accepted by all? Is this an on-going process or has Malaysia turned the poetic corner, so to speak, and embraced all of these voices, enriching the literature of Malaysia in the process?

Edwin: Malaysians write in an English which is quite distinctive. We can recognize Malaysian English both in its standard and non-standard forms. We can see the influences of the local languages on Malaysian English and it certainly enriches the language, but we need to bear in mind that it should have intelligibility for both local and international readers.

Writing in English in Malaysia has not been easy. Having the writers’ voices heard is a good start. We do not have many publishers who want to publish poetry. There is the option of self-publication. Even established poets like Wong Phui Nam self-publish. Most poets look for options abroad and online literary journals. It slightly better if you are publishing prose but that too is very limited though the opportunities are more in the last few years.

Those who write in English in Malaysia do not get any governmental support unlike those who write in the Malay language. This lack of support has not deterred the writers as we see many more young people writing in English than ever before.

There are some success stories of Malaysians publishing in English who have won awards and received international recognition. The first person to win such an award was Shirley Geok-lin Lim in 1981 when she won the Commonwealth Poetry Prize for a debut volume. Tan Twan Eng, Tash Aw and Rani Manicka have won prizes for their novels. This year, Saras Manickam won the Commonwealth Short Story Prize for Asia. So, it is looking good for Malaysia, writing in English. As a literary tradition, we are only about sixty years old. There is a lot of diversity in the writing and that for me makes Malaysian writing in English rather vibrant.

RR: Plus Ivy Ngeow’s Cry of the Flying Rhino and Bernice Chauly’s Once We Were There both won prizes. Having witnessed that transition in the thirty plus years since I first came to Malaysia, I wholeheartedly agree.

Anthologies...poetry...short stories...is a novel the next in your future offerings, or is that risking going too far?

Edwin: I am working on a number of projects. I hope to bring out a collection of Malaysian short stories, similar to that of Malchin Testament: Malaysian Poems. It’s ready to go to the publisher. This project has taken a lot of time as I want it to be representative of stories from the 1960s to the present.

I have also been writing poems and short stories. This I do constantly. I’ve re-written couple of my short stories into scripts, hoping they will be staged at some point. I was very encouraged when three of my stories from Coitus Interrupted and Other Stories were used to stage a performance called ‘Love Matters’ in Mumbai by Playpen Performing Arts Trust directed by Ashish Joshi in 2017 and 2018.

I would look to write a novel but maybe not yet. Some of my short stories could have the seeds for a full-blown novel, we’ll have to wait and see.

RR: Back in the 1990’s, I used to be the Penang Coordinator at MACEE, the Malaysian-American Commission on Education Exchange, which was run under the Fulbright Program. As a recipient of a Fulbright Scholarship, tell us about your Fulbright experience. How has the program impacted your writing and your professional life?

Edwin: I totally enjoyed my Fulbright experience. It was the first of a series that was called “Reading America”. We started at New School University, New York where we were given lectures on a variety of topics ranging from literature to politics and history. New York City was in itself a learning experience. There’s so much to see and do. Going to the New York University Library and having access to use it was very exciting for me. I was in all the bookshops, especially Strand. There were theatres, museums and art galleries to go to. I can just go on.

We then went to New Mexico. Here we had a few tours and going to the native Indians reservations was an amazing experience. Made me feel rather sad when we were told about the history and violent past with the white settlers. A highlight in the New Mexico section was going to Georgia O’ Keeffe’s house and seeing her work. Finally, we went to Washington D.C. Here, we received various guided tours, including the White House and some monuments. The visit to Library of Congress is something I will remember. What an amazing library both architecturally and in terms of its collection of materials.

The Fulbright program provided an excellent opportunity for networking. There were about twenty of us from different countries who shared similar interests, mostly literature. We are still in contact and I’ve been to visit some of them. We continue to communicate and read each other’s work. This has certainly contributed in our professional lives.

RR: I'm sure it did. Hopefully you'll inspire other writers to apply. I once had an amusing experience with Fulbright in Kuala Lumpur when attending a formal dinner in the mid-1990s. The set menu consisted of, among several delicious dishes, two Brussel sprouts, which I thought a rather peculiar choice. I wondered who had taken the poetic licence to suggest such an unpopular dish for the menu of a formal dinner filled with hundreds of Fulbright scholars, Malaysian government officials, and international dignitaries? No doubt, someone very important and everyone was afraid to say, “Aiyoh, are you crazy?” Instead they meekly shook their heads in agreement. Not to anyone’s surprise (I call it poetic justice), those same two Brussel sprouts were the only untouched items left on the hundreds of plates taken away by the waiters.

What else would you like us to know about you, about your writing, or any writing topic that you feel passionate about that needs addressing?

Edwin: I like to present a Malaysian Indian perspective which is contemporary but also deals with the past. The past is very important to me, for example the loss of people and places. Brickfields, my birthplace, features in my poems. I like to write about loss, longing and loving. My hope is that my treatment of these themes and issues will be different and will give a fresh and unique perspective.

I am currently doing a book tour to many universities. The purpose of this tour is to meet my readers and potential readers. It gives me an opportunity to meet young people and very much want to share my love for poetry and literature. So far, I’ve visited about eight universities in Peninsular Malaysia, one in Sarawak, one in Singapore and two in Taiwan.

RR: What advice would you give young poets or writers who are struggling to finish (or even seriously start) their first book?

Edwin: If you want to write, my advice is to read. Read widely and read as much as you can. That is certainly the first step towards becoming a writer. I would advise writers to have reading buddies. People who you could trust to be honest with you about your work. Also, a poet or short story writer, one could send poems and stories to literary journals and online magazines. Many of these are peer-reviewed and they often give useful feedback; getting them published is certainly a great way of building one’s confidence. Hopefully, with this one publication they will have enough writings and confidence to get more work published, possibly even a book.

Other Interviews with First Novelists:

Ivy Ngeow author of Cry of the Flying Rhino, winner of the 2016 Proverse Prize.

Golda Mowe author of Iban Dream and Iban Journey.

Preeta Samarasan author of Evening is the Whole Day.

Chuah Guat Eng , author of Echoes of Silence and Days of Change.

Five part Maugham and Me series

Published on July 18, 2019 04:57

January 18, 2019

Neighbors: A Suicide and Making Choices or How to Turn Your Story into the Right Story

I learned firsthand when my neighbor committed suicide (the neighbor who inspired my short story “Neighbours” that featured the gossip Mrs. Koh (“Are You Mrs. Koh?”): When someone dies, people will ask how did they die? When someone commits suicide, people will tell you why they died…

After discovering an unpleasant mess with my old website that sent all of my blog links to the story astray (to put it mildly), I re-posted the story and re-linked it to various blogs going back ten years…. While doing so, I got to thinking about “Neighbours”, why I wrote it and why I chose to focus on that aspect of the story and not the whole story. I first touched upon this in an old blog (later published in Tropical Affairs) that I wrote soon after “Neighbors” (using the American spelling) had been accepted for publication in the American literary journal Thema — twenty years after I first wrote the story for a Malaysian contest. The story, from Lovers and Strangers Revisited, was then taught for six years (2008-2014) in SPM literature and in various private colleges and universities throughout Malaysia, and translated into French along with the rest of the collection. Writing, I used to tell my students, is about making choices. If you choose wisely you might surprise yourself with the story you end up with. For example in “Neighbors”, I could’ve written a nonfiction narrative or a different story starting with my hearing some groans coming from my neighbor’s house, two doors away. When I investigated, I found an elderly Chinese man lying helpless on the couch. His door was locked, yet in between moaning he managed to tell me that the keys were by the sink, which I was able to obtain by reaching through the grille at the kitchen window. With the help of another Chinese neighbor (whose wife was pregnant and very upset that he was getting involved), we took him to the General Hospital.

After discovering an unpleasant mess with my old website that sent all of my blog links to the story astray (to put it mildly), I re-posted the story and re-linked it to various blogs going back ten years…. While doing so, I got to thinking about “Neighbours”, why I wrote it and why I chose to focus on that aspect of the story and not the whole story. I first touched upon this in an old blog (later published in Tropical Affairs) that I wrote soon after “Neighbors” (using the American spelling) had been accepted for publication in the American literary journal Thema — twenty years after I first wrote the story for a Malaysian contest. The story, from Lovers and Strangers Revisited, was then taught for six years (2008-2014) in SPM literature and in various private colleges and universities throughout Malaysia, and translated into French along with the rest of the collection. Writing, I used to tell my students, is about making choices. If you choose wisely you might surprise yourself with the story you end up with. For example in “Neighbors”, I could’ve written a nonfiction narrative or a different story starting with my hearing some groans coming from my neighbor’s house, two doors away. When I investigated, I found an elderly Chinese man lying helpless on the couch. His door was locked, yet in between moaning he managed to tell me that the keys were by the sink, which I was able to obtain by reaching through the grille at the kitchen window. With the help of another Chinese neighbor (whose wife was pregnant and very upset that he was getting involved), we took him to the General Hospital.I could’ve written about the hospital’s reaction to me, a young white man attending to this elderly Chinese man who was dying, their giving me strange looks as I wrote in my journal, trying to get all the details and my impressions while they were still fresh — the writer part of me at work; and then my anger at the doctors and nurses who seemed indifferent about my neighbor’s plight. He was dying and no one wanted to help!

Since the doctors didn’t know what poison he had taken, I volunteered to go back to his house. Although I often chatted with this neighbor across the gate or his fence, I had never ventured inside his house. I could’ve written about the eerie feeling I had wandering inside this empty house where a man had just tried to kill himself. Upstairs I located two glasses of beer and some green liquid, which I took to the hospital.

Since this was in the mid-80s before CSI, the doctors wanted me to go back to the house once more to find out what the green stuff was. So back I went and eventually found, hidden behind a partition, a bottle of the weed killer, Paraquat. By then there was nothing the doctors could do, so I stayed with this man for several hours at the hospital, while we tried, without success, to contact his family. I didn’t want him to die alone like another expat that I wrote about who had died alone in a faraway land.

I could’ve written about my attending the three-day Chinese (Teochew) funeral held outside their house, which was very lively and noisy and attracted a lot of attention from the other Chinese neighbors. When it was over, I was invited back to the house and given a gift, a token of appreciation for what I had done for this family.

The family, however, refused to live in the house anymore because of this suicide. Months later, another family had moved in, but they kept hearing mysterious noises — like someone walking around upstairs in the master bedroom — and it was scaring the children. The family didn’t know about the suicide until after they had decided to leave. Malaysians, particularly the Chinese, take ghosts and spirits very seriously.

None of this mattered to the story that I wanted to write. For me the story began when I returned from the hospital to the man’s house and found several neighbors gossiping.

I was fascinated by all of the comments the neighbors made, the wild speculations about the family and why the man had taken his life. Some of the things they had said were mean and spiteful. Later, when the man’s wife and daughter returned home, the neighbors quickly dispersed; they refused to inform them about the man’s death. Even though I was the newest neighbor and an expat, I had to bear the bad tidings alone.

This was the story that fascinated me. The story I wanted to tell was not a first person narrative of my finding this man and all that took place that day (although I could still write about it since it’s in my journal as either non-fiction or incorporate it into another story or as part of a novel — it’s all there to be used, grist for the mill as writers often say).

Instead, I chose to write about the neighbors themselves and what they said about this family in the aftermath of the suicide. In fact ‘Aftermath’ was the original title when it was first published in Singapore and Australia and in Lovers and Strangers (Heinemann Asia, 1993). Again thanks to my journal, all the details were there, still fresh, including those that had completely slipped my memory after several years had already passed, one of the reasons I urged my writing students to keep a diary/journal.

Instead, I chose to write about the neighbors themselves and what they said about this family in the aftermath of the suicide. In fact ‘Aftermath’ was the original title when it was first published in Singapore and Australia and in Lovers and Strangers (Heinemann Asia, 1993). Again thanks to my journal, all the details were there, still fresh, including those that had completely slipped my memory after several years had already passed, one of the reasons I urged my writing students to keep a diary/journal.Another choice I made was to leave me, as a character, out of the story. I felt it would be better without a Westerner or a mat salleh in it. I wanted the dialogue to be natural, spontaneous, and an expat present would alter the dynamics of the group, including the dialogue. Also I wanted to shift the sympathy to this man and his family — even after hearing many bad things about them.

I purposely wrote the story in a neutral tone with the viewpoint of an observer, to avoid racial bias, so no one race in this multi-racial society is talking down to another. Yet, at the same time, all Malaysians should be able to identify with these characters. They could be your very own neighbor or a relative, hopefully distant....I wanted to make the story universal, so readers around the world could relate to the characters and also learn about Malaysia, where different races freely mix and socialize, and yes, gossip.

When writing your story, whether it is based on a true dramatic incident or nor, or whether it is fiction or nonfiction, ask yourself, do you want to write the whole story or just one aspect of that story? Consider your choices carefully. I did and thirty years later the story keeps paying off in unforeseen ways.

Then again, it is always hard to keep a good story down, especially when it involves a suicide and neighbors gossiping. At times, we all love a good gossip. Just ask Mrs. Koh. # # #

Later I had blogged about the significant changes that I made in *“Neighbours” that led to its initial publication, and the subsequent revisions for publications overseas and in various book form (three publishers and a French translation), which I noted in the series The Story Behind the Story, used by teachers as an aide for their students. MELTA (Malaysia English Language Teaching Association) had even created an on-line discussion for “Neighbours” for students and teachers on their literature forum, which had over 20,500 hits and 30 pages of comments about the story and Mrs. Koh before it was archived and later take down.

*The link to the short story “Neighbours” is the revised version, written in the present tense, after the French translation of Lovers and Strangers Revisited came out.

—Borneo Expat Writer

Published on January 18, 2019 05:19

January 15, 2019

"Neighbours" by Robert Raymer

“I suppose there’s a mess in the back seat,” Mrs. Koh says, her face flushed, her arms crossed as she stands in front of Johnny Leong’s terrace house. She shakes her head and waits impatiently for Koh and Tan to get out of the car. “You just had to volunteer our new car, didn’t you? Why didn’t you borrow someone else’s car like I told you, or wait for an ambulance? Now it’s ruined. Ruined!” Koh doesn’t bother to respond. He stretches and then rubs his aching back. His attention is drawn to the mournful sound of someone playing the saxophone. Koh and Tan are Johnny’s immediate neighbors. The Koh’s terrace house is on the left, while Tan, a bachelor, lives on the right. The medium-income housing area is new, less than two years old. Malays, Chinese and Indians live together in relative harmony – a mini Malaysia. The streets are narrow, though, and there are no sidewalks to walk on; because of the uncovered monsoon drains, neighbors have to walk in the street and chat there, too, moving aside to let an occasional car pass. Across the street, Miss Chee, a secondary school teacher, unlocks her gate and lets out her white Pomeranian Spitz. Miss Chee is tall and thin with short black hair and razor-sharp bangs. Upon noticing Mr. and Mrs. Koh standing in front of Leong’s gate, she waves and crosses the street to join them. She’s halfway there when she realizes that Tan, the new math teacher at Penang Free School, is with them. She blushes, but it’s too late to turn back or he may think she’s avoiding him or being rude. Mrs. Koh is bent over peering through the side window of the car. She doesn’t see any mess, though she’s convinced the evidence is just waiting for her to find. She looks up in time to see Miss Chee approaching. Before anyone else has a chance to speak, Mrs. Koh blurts out, “Hear about Johnny?” Taken aback, Miss Chee asks a bit nervously, “Were he and Veronica fighting again?” Mrs. Koh’s beady eyes light up like shiny new coins. “Did you hear them fighting this morning?” She turns to her husband with an I-told-you-so look on her face. “Wait a minute, were they fighting?” Tan asks, glancing at Koh. “No, they weren’t fighting,” Koh says, glaring at his wife. “I told you that already. I was outside all morning, and I would’ve heard them.” “I didn’t think so,” Tan says, adjusting his glasses. “When Veronica and Lily passed by my house, they both seemed fine. In fact, they smiled and waved like they usually do.” Mrs. Koh twitches her nose. “Veronica didn’t say where they were going, did she? Gambling, that’s where! Every Sunday she plays mahjong and I’m sure she’s in debt!” She pauses to catch their surprised reaction. To prove her point, she adds, “She once tried to borrow money from Koh.” “She only wanted five ringgit-lah, to buy some vegetables,” Koh says, shaking his head. “She didn’t have time to go to the bank.” “You’re not her bank either, otherwise she’d be borrowing from you all the time,” Mrs. Koh says. “Thank heavens you didn’t give her any.” “You wouldn’t let me,” he says, “and she’s our neighbor!” “It’s bad enough she’s always collecting advance money for her catering, and now that Johnny’s dead–” Miss Chee’s mouth drops open. “Dead?” “He’s not dead yet,” Koh says to his wife. “He’s still breathing.” “Dead? Still breathing?” Miss Chee’s mouth goes slack as she looks from Koh to Tan for some answers. “He’s as good as dead,” snaps Mrs. Koh. “I don’t understand,” Miss Chee gasps in frustration. “Who? Who are you talking about? Johnny? Is he all right?” “All right? He’s all wrong,” Mrs. Koh says. “Him and his whole family!” “Johnny tried to commit suicide this morning,” Koh says to Miss Chee. “Wah! But why?” “Because Veronica ran up all those gambling debts!” Mrs. Koh says. Koh glowers at his wife and says, “We don’t know that. We do know he drank weed-killer. He was drinking it with his beer.” Mrs. Koh plants her hands squarely on her hips. “Drinking! That’s all that man ever did – sit around and drink. And that – that Veronica! The way she lets that daughter of hers run around like some tramp!” Miss Chee’s eyes open wide. “Lily? She’s an all-A student.” She leans toward Tan and says in a low voice, “Lily is my best student.” Tan nods and smiles at her politely. Again he adjusts his glasses even though they are fine. Miss Chee hesitates, but then she asks Tan, “What time did you find Johnny?” “Just before noon,” Koh replies. “Isn’t that right, Tan?” “Yes, about noon.” Mrs. Koh nods. “Koh told me he heard Johnny groaning one hour after Veronica took Lily gambling. I just happened to look at my watch when they passed by.” “I didn’t hear the groaning until after Tan called me from his gate,” Koh says, adding a salute to Tan. “If it wasn’t for Tan, Johnny might already be dead.” “And you had to put him in our brand new car!” Mrs. Koh says. “Just imagine if he died there. All the bad luck it’d bring, and with the New Year around the corner! We’d have to sell it, and it’s not even two months old!”

Dr. Nathan, an Indian dentist who lives next door to Miss Chee, waves at them as he slows down his car. He stops in front of his gate, gets out and unlocks it before driving inside. Again he smiles and waves and crosses the street to join them. He extends his hand to Koh, one of his patients.

“A fine Sunday afternoon,” Nathan says. “Not for Johnny,” Mrs. Koh replies, “he’s dead.” “Alamak!” “He’s not dead yet,” Koh says, and shakes Nathan’s hand. “Tan and I just took Johnny to the General Hospital. He tried to commit suicide by drinking Paraquat. We managed to contact his son, and he’s over there now. Veronica and Lily haven’t been told yet. We don’t know how to contact them.” “For heaven’s sake,” Nathan says, and looks as if he just pulled the wrong tooth. “I never realized. Just last New Year – yes, it was just last New Year Johnny had that party and everyone was there, having a grand time.” “Especially Koh,” Mrs. Koh says, eyeing him. “He was so drunk I had to drag him home.” “I was not drunk – just celebrating.” “Celebrating, ha! That’s what you call it! You had a hangover and missed work for two days!” “I was on annual leave,” Koh corrects. “Same thing. You missed work!” Nathan rubs his balding head and asks, “Who found Johnny?” Miss Chee nods at Tan and says, “Mr. Tan did. He heard Johnny groaning.” “I can’t take all the credit, Miss Chee. Your name is Miss Chee, am I correct?” “Why yes, it is,” Miss Chee replies, her smile widening. “My friends call me Alice.” “My friends and my patients call me Nathan,” Nathan says, and offers his hand to Tan. Tan introduces himself. “Anyway, it was Koh who was the first one inside the house,” Tan said. “He called the ambulance, too.” “But we decided not to wait,” Koh says. “The hospital kept asking all these foolish questions that we couldn’t answer, so we took him in ourselves.” “In our BRAND NEW CAR!” adds Mrs. Koh. “Really? You have a new car, I never realized,” Nathan says. “I remember my first new car, a Proton Saga – the very year it came out, mind you. Our national car. We’ve certainly come along way since Independence, haven’t we?” Nathan’s smile overflows with pride. “Now Johnny, he was a good neighbor. Yes, a good neighbor, even though he stills owes me for treatment. Root canals aren’t cheap, you know.” “That reminds me,” Koh says, “my tooth has been hurting again.” “Oh, dear,” Nathan says. “You mustn’t wait, or you could find yourself in a lot of pain. That’s what happened to Johnny. He waited until the pain was simply unbearable.” “Should I call your office for an appointment or just drop by?” Two passing motorcycles drown out Nathan’s reply. Miss Chee’s dog barks and feigns a chase. After a few frantic steps, it comes back to Miss Chee. “Ramli’s kids!” Mrs. Koh says, staring down the street after them. “Race here, race there. And last week I saw one of them teaching Lily how to ride. I don’t know why Veronica lets her daughter – at that age – run around with boys. I’d never let my daughter do that! And today, of all days, she takes Lily gambling!” Nathan scratches his left ear. “Oh dear, I never realized Veronica gambles.” Mrs. Koh is nodding. “Every Sunday she goes to her cousin’s house in Air Itam. That’s where she gambles! Every Sunday!” “You told me you had no idea where Veronica went,” Koh says, annoyed, frowning at his wife. “Johnny’s son was trying to reach her.” Mrs. Koh crosses her arms in defiance. “It’s none of my business where she gambles!” “You should never gamble with your teeth,” Nathan says to Tan, and passes him a business card. “If you ever need a reliable dentist, I live right across the street. You can’t get more reliable than a neighbor.” Ramli, an elderly Malay who sells satay at the night markets, is walking down the middle of the street in their direction. His back is ramrod straight as he nods to Tan, one of his regular customers. “My eldest daughter tells me Johnny hasn’t been at school the past three days,” Ramli says. “Then yesterday she saw him walking along the main road carrying a helmet without his motorcycle. Imagine that!” Miss Chee asks Tan, in a low voice, “Is Johnny a teacher, too?” “No,” Tan replies, “he’s a janitor at my school.” “A dead janitor,” adds Mrs. Koh. “Dead? Don’t talk about dead. No joke-lah!” Ramli gazes from face to face as if he missed the punch line to a sick joke, though he’s hoping someone will explain it to him. “So, who’s dead? Huh?” “Johnny, but he’s not quite dead – at least not yet,” Koh says. “But he did try to kill himself by drinking Paraquat.” “Paraquat? Ya Allah!” Ramli’s dark brown eyes roll upwards toward heaven. “Koh heard him groaning around noon,” Mrs. Koh says. “One hour after Veronica took Lily gambling.” “Wasn’t it Tan who heard the groaning?” asks Miss Chee. She glances at Tan for confirmation. Koh nods. “That’s right. If it wasn’t for Tan, Johnny might already be dead.” “It has to be about money-lah,” Ramli says to no one in particular. Everyone looks at him. “Why else would he sell his motorcycle?” “He’s right-lah,” Koh says. “Why else?” “Unless he’s involved with a woman!” Mrs. Koh says. “Wouldn’t surprise me!” Tan and Ramli glance at one another and shrug as if suggesting that it’s possible. “Gambling, drinking, womanizing – what a family!” Mrs. Koh says. “Now I’ll never get that root canal bill paid,” Nathan says, and grimaces. “I’m sure Johnny has some insurance somewhere,” Tan says, trying to be helpful. Koh frowns as if he just found chewing gum stuck to the bottom of his shoe. “Well if he does, he didn’t buy it from me,” Koh says. “I must’ve asked him a half dozen times. What good did it do me? And I’m his neighbor!” “So am I,” Ramli says. “In fact, one of my sons offered to buy his motorcycle for its license plate number for good money, too. Now look at what he did, sold it to someone else. A stranger!” Miss Chee watches her dog go back and forth across the street. She sighs in exasperation and says, “It’s a good thing Veronica has that catering business to fall back on, if worst comes to worst.” She catches Tan’s gaze. “Are you buying from her, too?” “Well, no, not yet,” Tan replies, “but I was thinking about it.” “It must be difficult living on your own like that.” “I’ve been living on my own for fifteen years,” Nathan says, “and I can cook, too.” Miss Chee smiles politely. “Now if Johnny doesn’t make it–” “He won’t if he drank Paraquat,” Ramli says. “That one’s a sure killer.” “Either way,” Miss Chee says, “I’m sure the good Lord will look after Veronica and Lily.” “Are they Christians?” Tan asks. “He has a Christian name, doesn’t he?” Mrs. Koh says. “Veronica and Lily, too!” “Come to think of it, I don’t think they are,” Koh says, scratching his head. “In fact, I think they’re Buddhists. Or used to be. With Johnny, you can never tell. Besides, back in school many of us added Christian names but we weren’t Christian. Even you did, long before you converted.” “That doesn’t make it right,” Mrs. Koh says. “It’s misleading!” Tan says, “Unless I’m mistaken, Johnny once told me he was a free-thinker.” Koh laughs. “That’s Johnny for you. He liked everything free.” “You should know,” Mrs. Koh says, “you were always there drinking his free beer.” “You’re just jealous Johnny never asks you to come along.” “I wouldn’t go over there even if Johnny and Veronica begged me to.” Tan gazes at the round table not far from Johnny’s gate. He clears his voice and says to Miss Chee, “We used to sit there and talk. The very night I moved in – even though I was a total stranger – Johnny invited me over. We must’ve sat up half the night philosophizing about everything under the sun.” Guilt creeps into his eyes. “Just last night I was over there.” “I saw you.” Miss Chee blushes as Tan looks at her with surprise. “I happened to glance down from my bedroom window.” Tan looks up at the window and then at Miss Chee. “I think Johnny was just a lonely man,” Tan says. “You think he’s lonely?” Nathan says. “My wife has been dead fifteen years. Fifteen years! Johnny can’t be lonely, not with a wife and daughter at home. And his son comes visiting often enough.” “Johnny has a son?” Ramli ponders this. “I thought he only has a daughter.” “Danny’s his name,” Miss Chee says. “He was one of my first students. A bright student at that.” “Yes, we had a long talk at that New Year party,” Nathan says. “Danny’s a good boy with a good job.” “Good boy, ha!” Mrs. Koh says. “Ever since he became a big shot at the bank, he certainly acts like one – living in town and wasting money paying extra rent. What for? A good boy would stay at home and help his father pay the bills, especially the way Veronica gambles and throws away money on Lily. Always buying her the latest styles.” “At least Veronica works,” Koh says. Mrs. Koh twitches her nose. “Her food isn’t much to talk about. So bland! And she’s always asking for advance money. Why can’t her son give her some of his money? Huh?” “I wish my elder two sons would settle down and find good jobs like that,” Ramli says. “Before I was twenty, I had a job, a house and a wife! Back in those days, boys had more responsibilities.” “It sure would be nice if your sons stopped racing up and down the street,” Mrs. Koh says. “The noise is deafening!” “See! See! That’s what happens when grown boys stay at home,” Ramli says, and raises his arms in surrender. “They get restless! Only a wife will settle them down. A wife and a job will teach them some responsibilities. If you ask me, Johnny had it too easy. Too easy. He has a working wife and only two children. One living on his own like that. Look at me, six of them, and a mother-in law at home who’s driving me crazy! You don’t see me committing suicide, do you?” Mrs. Koh stares past Nathan’s shoulder to one of the houses further up the street. “Who’s playing that – that thing, anyway?” “It’s a saxophone,” Koh says. He fingers his mole hair and listens more closely. Mrs. Koh says, “People shouldn’t play those things unless they already know how!” “If he doesn’t practice,” Koh says, “how can he know how? When I was a boy, I had an old trumpet and would practice all day.” Koh smiles to himself and closes his eyes, remembering. Ramli strains his neck to see around the others. “Here comes Veronica.” All of them turn to look. Veronica and Lily are walking side by side, each carrying several plastic bags. Koh turns to his wife. “Looks like they didn’t go gambling at all! Just shopping.” Mrs. Koh twitches her nose in defiance. She peers around their car to get a better look. Miss Chee asks, “Think she knows about Johnny?” Mrs. Koh shakes her head. “I bet she was too busy spending all her money on that daughter of hers to know anything.” “If you ask me,” Ramli says, “Johnny had it too easy. Too easy.” “I hope they don’t move,” Miss Chee says. “Lily is my best student.” “Don’t even mention it,” Nathan says, “or I’ll lose two more patients.” “Of course they’ll move,” Mrs. Koh says. “Wouldn’t you move if your husband commits suicide in your own home?” “I’m not married,” Miss Chee replies, and glances at Tan. “Hey, what time is it?” Koh asks. “There’s a football match I want to watch!” “Oh my, it’s nearly two,” Nathan says, glancing at the time. “I haven’t had my lunch yet. No wonder I feel hungry.” “Two? Already? I got to run-lah,” Koh says, and hurries next door. Tan asks, “Who’s going to tell Veronica?” Miss Chee looks down at her dog. Ramli and Nathan both shrug as they return to their respective terrace houses. “Not me,” says Mrs. Koh, leaving before Veronica and Lily arrive at the gate. “It’s none of my business.”# # #*I posted this to replace the older version from my previous website since it was no longer available and I had links to the story in dozens of "Neighbour" related blogs.

Published on January 15, 2019 18:48

January 9, 2019

My interview with Chuah Guat Eng is in Blue Lotus 16

My interview with Chuah Guat Eng, author of Echoes of Silence and Days of Change, is in Blue Lotus 16, 2019, pages 8-25. Originally I had blogged about our interview in October 2018.

My other interviews with Preeta Samarasan, author of Evening is the Whole Day, was published in Blue Lotus 12, Ivy Ngeow, Cry of the Flying Rhino, in Blue Lotus 13 and Golda Mowe, author of Iban Dream and Iban Journey, in Blue Lotus 15

Links to the other blog interviews with first novelists:

Ivy Ngeow author of Cry of the Flying Rhino, winner of the 2016 Proverse Prize.

Golda Mowe author of Iban Dream and Iban Journey.

Preeta Samarasan author of Evening is the Whole Day.

Five part Maugham and Me series

—Borneo Expat Writer

Published on January 09, 2019 05:26

January 3, 2019

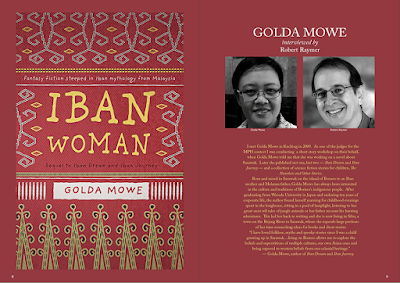

My interview with Golda Mowe is in Blue Lotus 15

My interview with Golda Mowe, author of Iban Dreams and Iban Journey, and the new sequel Iban Woman, is in Blue Lotus 15, 2018, pages 8-21. Originally I had blogged about our interview in 2017.

My other interviews with Preeta Samarasan, author of Evening is the Whole Day, was published in Blue Lotus 12and Ivy Ngeow, Cry of the Flying Rhino, in Blue Lotus 13.

Other interviews with first novelists include:

Chuah Guat Eng, author of Echoes of Silence and Days of Change.

Along with:

Ivy Ngeow author of Cry of the Flying Rhino, winner of the 2016 Proverse Prize.

Golda Mowe author of Iban Dream and Iban Journey.

Preeta Samarasan author of Evening is the Whole Day.

Five part Maugham and Me series

—Borneo Expat Writer

Published on January 03, 2019 05:59

October 17, 2018

INTERVIEW CHUAH GUAT ENG: Robert Raymer Chats with Malaysian Author Chuah Guat Eng on Writing and Publishing her Novels

I first met Chuah Guat Eng, if I’m not mistaken, when Sharon Bakar invited both of us to read our respective work at a Reading@Seksan event in Kuala Lumpur in 2009. I had also picked up a signed copy of her first novel, Echoes of Silence(1994, 2008), which has the distinction of being the first novel written in English by a Malaysian woman. Her second novel, Days of Change(2010), a sequel, made the long list for International Dublin Literary Award in 2012. She is currently working on Whispers of Truth, her third novel that continues the series.

Guat Eng read English Literature at University of Malaya Kuala Lumpur, German Literature at Ludwig-Maximilian University Munich, Germany, and received a Ph.D. in 2008 from the Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia for her thesis, From Conflict to Insight: A Zen-based Reading Procedure for the Analysis of Fiction. She was a Post-doctoral Research Fellow at Universiti Putra Malaysia from January 2011 to March 2013, focusing on Malaysian novels in English. Currently she teaches part-time at University of Nottingham Malaysia and at the Faculty of Cinematic Arts, Multimedia University Johor on subjects related to literature and creative writing.

She has also published three collections of short stories, Tales from the Baram River(2001), The Old House and Other Stories(2008), and Dream Stuff (2014).

Praise for Echoes of Silence…‘…an intellectual as well as a tender novel about love…entertaining...intelligent…well-crafted…’ – T. Dorall, New Straits Times

‘…more postmodern than at first appears…the most accomplished Malaysian novel to date, a new and cultured voice…’ – Jun Mo, Far Eastern Economic Review

“In March 1970, as a direct result of the May 1969 racial riots, I left Malaysia.” Thus begins Echoes of Silence, the story of Lim Ai Lian, a Chinese Malaysian. While studying in Germany, she falls in love with Michael Templeton, an English gentleman brought up in the district of Ulu Banir, where his father, Jonathan Templeton, owns a plantation. While trying to solve a murder, Ai Lian, learns about racial prejudice, truth and deception, womanhood and love, and how past silences can echo into the present.