Alexander Chee's Blog, page 5

April 21, 2012

On Distractions, Briefly

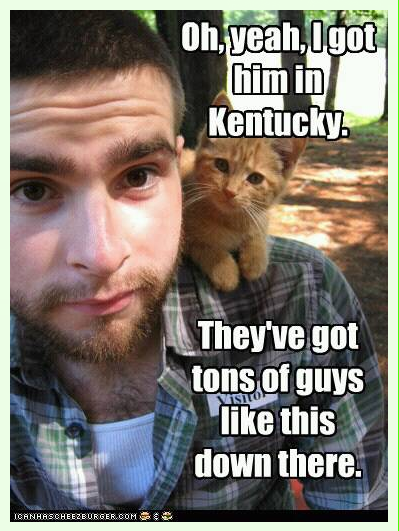

Nothing in this post explains your fascination with cats. Or does it?

Last night at the One Story Debutante’s Ball, I was talking briefly to a friend who was complimenting me and Colson Whitehead on our ability to maintain our focus on our work while also being on social media. Colson has written about it and what he said was basically consistent with his hilarious and very true column over at PW. I agreed. But I also have a theory about all of the distractable types: there’s a very good chance you’re not writing because you’re not writing about what you actually want to write about.

This may sound improbable to some–isn’t writing about Freedom? Yes. Writing is so much about Freedom, you can’t even say writing is about Freedom, actually, without feeling despair. No, what I mean is something else–the writer in the grip of the ostentatious obligation to Make Literature, creating something that looks like what they think a story or novel is, instead of a story or novel. If you neglect your own writing, chances are something, or someone, or both, have given you the idea that your Freedom is missing. That you’re not free to do as you want. Surfing the internet feels a lot like being Free. So, you do that instead of your work.

The next time you find yourself helplessly in the grip of some internet rabbit hole, take a slight step back, and don’t stop yourself, but ask yourself what it is you are really after. What are the feelings you feel? The rabbit hole isn’t real, it’s the force of your own rejected interests, in doing a dance with the internet. Which is to say, you’re actually in control–there’s something you want to do that you’re not doing and you’re not facing it.

Do you feel helpless about the war, the environment, your job, your health, the health of your friend/family member/partner/boyfriend/girlfriend, your writing? Do you feel that if you wrote what it is you really wanted to write you’d be judged in some way you fear? I.e., are you furiously looking at porn sites because you feel some important part of you is rejected by your life in some way the porn site actually… cannot either affirm or reject?

Or, this last bit: whatever it is that is so distracting, would you write more if you wrote about it? Does it want, in other words, to be your subject?

Think about it. And meanwhile, celebrate short fiction this spring with a subscription to One Story.

April 6, 2012

True Story at KGB Bar, with Maud Newton, Tuesday, April 10th

This Tuesday, April 10th, 7PM, at KGB Bar here in New York, I'll be reading with my good friend Maud Newton. Maud is one of my very favorite people ever. We met on Facebook, over a shared love of Jean Rhys that turned into this exchange over at Granta, and since then, we've shared our struggles on writing, work and life, as well as some fine food and drink, and notable Karaoke (Her rendition of "9 to 5″ is a revelation).

In preparation for this reading Maud and I shared drafts, a process that lead to us both uncovering what we were actually writing about. As Maud put it over on her blog, "Both of our essays are about family mysteries, conversations across generations". The essay I'll be reading from is something I've been working on for years off and on—it began as a garden diary of the sort every gardener is supposed to keep, back when I was growing roses in Brooklyn, and pretty soon I knew it was more than that, but only recently have I been able to finish it. Maud will read from an essay about a mystery in the life of her maternal grandfather that she decided to investigate that I, quite honestly, think is thrilling–and it is, in part, a testament to the power of research in writing about family, something not enough people do. Which is to say, you think you know about your family, but have you ever really checked out their story?

What I love about Maud as an essayist is that no matter the topic, whether it is personal or intellectual, she pursues it all with a trenchant honesty and self-regard, alongside scrupulous research, and a good portion of wit. If you don't know Maud's work, start with her self-titled blog, where she writes about her writing projects, books she is thinking about and her family's histories. There's a terrific interview with her here at Brad Listi's Other People podcast series (note her beautiful voice). She is at work on a novel, also, which is almost done. And if you perhaps somehow don't know her Twitter feed, well, you're missing out. So, don't—follow her here. And then, if you're in NYC this Tuesday, come find us.

March 30, 2012

Reader Nominations for the 2012 Million Writers Award Are Open

The Million Writers Award has championed writing published online long before it was possible to nominate work published online for the Pushcart, Best American and O. Henry. Nominations are open now, from now until April 9th, for readers to nominate work published online in 2011.

And yes, now that I mention it, I'd be thrilled if someone nominated My Next Move.*

* Editor's note: Thank you!

March 14, 2012

Britannica: Define Outdated – Room For Debate at the New York Times

Is it easier to search the digital edition? Yes, for the one thing you are there to find. But to find only the thing you are looking for transforms the limits of your imagination into the literal borders of what you know, and this is never a good thing.

Me, at the New York Times Room For Debate today, debating the merits of the Encyclopaedia Britannica becoming a digital only creature.

March 12, 2012

Ask Koreanish: On the Idea of a “MFA Safety School”

Periodically, I get readers writing in for advice. This is a semi-regular series.

Q: Is there any such thing as a safety school when it comes to MFAs?

A: I don’t know that safety school thinking applies.

In a general way, the graduate school experience is qualitatively different from the undergraduate school experience. When you’re an undergraduate, you’re typically looking for a liberal arts experience that will help you figure out your specific adult career goals in relationship to a broad education, conducted across a few disciplines. You may not find a match at that point but the idea is that you are at least prepared for whatever it is you do find after graduation–despite the bashing it gets, a proper undergraduate education really does prepare most people to write well across disciplines and think their way through problems of various kinds, including those not encountered in college. If successful, it endows critical thinking at a relatively high level. A safety school at this level makes sense–you’re looking for a place that will help you accomplish an undergraduate degree, a basic level of preparedness.

As a potential graduate student in the MFA, you are looking to specialize intensively, at least put yourself in the way of a mentor (mentor experiences are not guaranteed! They choose you) and meet, and this is important, a cohort–a group of individuals who will all be coming up together professionally. Your cohort in some ways is more important than a mentor, though no one thinks so at the time. Your cohort will be people you see for decades at your level or above or below, as time goes on, and they collectively can hold you to a high standard, a higher one than you might adopt for yourself. People always speak negatively about competition, but if it spurs you to your best efforts, I think there’s nothing negative about it at all—and that is really what you should let it do for you. That cohort you will have with you in class no matter who is teaching the class, and they’ll likely be the people you run into at readings and in cafes and bars and talk to, late into the evening, about literature. I learned to write a pantoum from a member of my cohort, for example. Every time I publish something I imagine what they will think before I present it, not after. Some will be suspicious of this admission, but I’m comfortable with it—I’m speaking of peers whose work I respect.

This group matters enormously because it is democratic and meritocratic both in its configuration, to a larger extent than it might be. It is more likely to have women and people of color in it than some other literary establishments, and your peers there will be writing with financial support that is neither a trust fund nor familial and spousal support–writing by virtue of a grant or fellowship they won from the school. They will often be people you would never otherwise agree to show your work to, and their experiences and readings will open up your idea of what you are saying, what is possible and how to proceed with what is possible.

For these reasons and more, I strongly advocate a “best places or no place” strategy. I.e., narrow down to what the schools are you’d want to go to and do not think in terms of safety schools. If you don’t get in, reapply the next year and work to improve until then. Or, move on and do not take the degree. And find your cohort in life—don’t think you can’t. You can. You just have to go outside as well as onto the internet.

Go big and go without a net, in other words, and see where it gets you.

Ask Koreanish: On the Idea of a "MFA Safety School"

Periodically, I get readers writing in for advice. This is a semi-regular series.

Q: Is there any such thing as a safety school when it comes to MFAs?

A: I don't know that safety school thinking applies.

In a general way, the graduate school experience is qualitatively different from the undergraduate school experience. When you're an undergraduate, you're typically looking for a liberal arts experience that will help you figure out your specific adult career goals in relationship to a broad education, conducted across a few disciplines. You may not find a match at that point but the idea is that you are at least prepared for whatever it is you do find after graduation–despite the bashing it gets, a proper undergraduate education really does prepare most people to write well across disciplines and think their way through problems of various kinds, including those not encountered in college. If successful, it endows critical thinking at a relatively high level. A safety school at this level makes sense–you're looking for a place that will help you accomplish an undergraduate degree, a basic level of preparedness.

As a potential graduate student in the MFA, you are looking to specialize intensively, at least put yourself in the way of a mentor (mentor experiences are not guaranteed! They choose you) and meet, and this is important, a cohort–a group of individuals who will all be coming up together professionally. Your cohort in some ways is more important than a mentor, though no one thinks so at the time. Your cohort will be people you see for decades at your level or above or below, as time goes on, and they collectively can hold you to a high standard, a higher one than you might adopt for yourself. People always speak negatively about competition, but if it spurs you to your best efforts, I think there's nothing negative about it at all—and that is really what you should let it do for you. That cohort you will have with you in class no matter who is teaching the class, and they'll likely be the people you run into at readings and in cafes and bars and talk to, late into the evening, about literature. I learned to write a pantoum from a member of my cohort, for example. Every time I publish something I imagine what they will think before I present it, not after. Some will be suspicious of this admission, but I'm comfortable with it—I'm speaking of peers whose work I respect.

This group matters enormously because it is democratic and meritocratic both in its configuration, to a larger extent than it might be. It is more likely to have women and people of color in it than some other literary establishments, and your peers there will be writing with financial support that is neither a trust fund nor familial and spousal support–writing by virtue of a grant or fellowship they won from the school. They will often be people you would never otherwise agree to show your work to, and their experiences and readings will open up your idea of what you are saying, what is possible and how to proceed with what is possible.

For these reasons and more, I strongly advocate a "best places or no place" strategy. I.e., narrow down to what the schools are you'd want to go to and do not think in terms of safety schools. If you don't get in, reapply the next year and work to improve until then. Or, move on and do not take the degree. And find your cohort in life—don't think you can't. You can. You just have to go outside as well as onto the internet.

Go big and go without a net, in other words, and see where it gets you.

March 9, 2012

Premonitions of the Literature to Come: Newton Arvin in Harper’s Bazaar, March 1947

I’m in Northampton, MA today, at the Smith College archives, where I am researching the life of Newton Arvin. My partner Dustin Schell and I are adapting Barry Werth’s biography of him, The Scarlet Professor, into a screenplay. Much of the story of him that is known is of a few shattering moments in 1960, when he became the center of a scandal after his arrest by the local police’s Pornography Squad. But here, among his papers, the celebrated critical mind that fostered writers as varied as Truman Capote, Carson McCullers and Sylvia Plath comes into view. I was struck by this paragraph from an article of his, ”The New American Writers”, published in Harper’s Bazaar, March 1947:

“The literature I can foresee coming into existence here may well be a profoundly realistic and even, in a better sense than the old one, a naturalistic literature. It would not be realism in the rather plodding and prosaic sense; it would be, I think, a form to which we could apply some such phrase as the one painter’s use—”Magical Realism.” It would not be naturalism in the old biological and documentary sense; but it might very well be–I believe it will be–naturalistic in a deeper and more genuinely human sense. I mean by this that it would be essentially faithful to the nature of things as we know them to be—to physical nature, of course, and to biological nature, but also to the nature of man himself, who, if he is an animal, is an animal of a very special sort, an animal whose mind deals most characteristically in symbols, and who can master his experience only when he has transmuted it in emblems, in allegories, in myths. A neo-naturalism, then, if you wish, a humanized and poeticized naturalosm, a naturalism not of the document but of the myth—such may well be the literature that the near future has in the making for us.”

Premonitions of the Literature to Come: Newton Arvin in Harper's Bazaar, March 1947

I'm in Northampton, MA today, at the Smith College archives, where I am researching the life of Newton Arvin. My partner Dustin Schell and I are adapting Barry Werth's biography of him, The Scarlet Professor, into a screenplay. Much of the story of him that is known is of a few shattering moments in 1960, when he became the center of a scandal after his arrest by the local police's Pornography Squad. But here, among his papers, the celebrated critical mind that fostered writers as varied as Truman Capote, Carson McCullers and Sylvia Plath comes into view. I was struck by this paragraph from an article of his, "The New American Writers", published in Harper's Bazaar, March 1947:

"The literature I can foresee coming into existence here may well be a profoundly realistic and even, in a better sense than the old one, a naturalistic literature. It would not be realism in the rather plodding and prosaic sense; it would be, I think, a form to which we could apply some such phrase as the one painter's use—"Magical Realism." It would not be naturalism in the old biological and documentary sense; but it might very well be–I believe it will be–naturalistic in a deeper and more genuinely human sense. I mean by this that it would be essentially faithful to the nature of things as we know them to be—to physical nature, of course, and to biological nature, but also to the nature of man himself, who, if he is an animal, is an animal of a very special sort, an animal whose mind deals most characteristically in symbols, and who can master his experience only when he has transmuted it in emblems, in allegories, in myths. A neo-naturalism, then, if you wish, a humanized and poeticized naturalosm, a naturalism not of the document but of the myth—such may well be the literature that the near future has in the making for us."

February 22, 2012

Two Lives, More

Janet Malcolm's Two Lives is a parade of everything I have been thinking about.

I've had the copy I'm reading for several years. While I wait for my edits to come back to me from my editor, and prepare for AWP next week, it's the perfect companion. To be specific, it is a book Janet Malcom wrote about Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas in France during World War II, or, even more specifically, as she puts it, "How did two elderly Jewish lesbians survive the Nazis?" But it also seems to be very much about what I spoke of in my most recent post, about self-belief. In this section, Malcolm is describing an awakening a young Gertrude Stein had after moving in with her brother Leo, who she loved, and who she had followed to Paris. He was the one who introduced her to Modernist art.

…Leo, too, was found wanting. "Slowly and in a way it was not astonishing but slowly I was knowing that I was a genius," and "There was no reason for it but he was not and that was the beginning of the ending and we always had been together and now we were never at all together. Little by little we never met again."

Malcolm returns with some thoughts on Leo:

Leo Stein's history is the all-too-common one of early promise coupled with the incapacity to fulfill it. He started and abandoned many careers—art historian, scientist, painter, and philospher. He couldn't finish anything. Some kind of hypercriticality kept him from doing so.

His hypercriticality extended apparently to his sister.

Leo was dismissive of Gertrude's writing—he belived she wrote the way she did because she couldn't write proper English—and he said something that Gertrude couldn't forgive. "He said it was not it it was I. If I was not there to be there with what I did then what I did would not be what it was," she writes in Everybody's Autobiography. "It did not trouble me," she adds. But in fact Leo's observation troubled her all her life and continues to trouble her posterity. "Perhaps after all they are right the Americans in being more interested in you than in the work you have done although they would not be interested in you if you had not done the work you had done," she writes elsewhere in the book.

I found this next section to be of particular interest, a few pages later:

Some years earlier, his job of making everything a pleasure for his sister had been taken over by Alice Toklas (who moved in with Gertrude and Leo in 1909), and his departure had something of the air of a shoe dropping. He and Gertrude divided the paintings and the furniture and parted forever.

It may in fact have been a hypercriticality that held him back in his various careers. It may also have been that before there was Alice B. Toklas, there was Leo. Given the furnace of need Stein is presented as in these pages, it's hard not to imagine all of his vitality being consumed in keeping things going for his younger sister, which he felt as an obligation akin to that of her lover, who replaced him.

A few pages earlier, Malcolm quotes from Stein writing about herself in The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas:

This faculty of Gertrude Stein of having everybody do anything for her puzzled the other drivers of the organization. Mrs. Lathrop who used to drive her own car said that nobody did these things for her. It was not only soldiers, a chauffeur would get off the seat of a private car in the Place Vendome and crank Stein's old Ford for her. Gertrude Stein said that the others looked so efficient, of course nobody would think of doing anything for them. Now as for herself she was not efficient, she was good humored, she was democratic, one person was as good as another, and she knew what she wanted done. If you are like that she says, anybody will do anything for you. The important thing, she insists, is that you must have deep down as the deepest thing in you a sense of equality. Then anybody will do anything for you.

It seems a strange fantasy, to believe that this deeply rooted democratic feeling… has as its product that anybody will become, effectively, your servant at that moment.

NB: I've never wrapped my head around the spectacle of Gertrude Stein writing the autobiography of her lover and companion–but of course, when would Alice have had the time to write one of her own? The answer being, after Stein's death, when the preoccupations of caring for her would have vanished. It was then she wrote first the famous The Alice B. Toklas Cookbook, and then her actual memoir, What is Remembered, which, ironically, I love, and have read in part because I love the tone of it, and it helped me in writing my own new book.

The portrait of Stein that is emerging thus far is a woman who must have gotten even the Nazis to cooperate in her care, though we'll see, I suppose–it's still early in the book. But the other portrait is of the lives around her, potentially emptied of everything except constantly caring for her. We'll never know if her older brother Leo really was brilliant and consumed by her, or if he would always have found an obstacle—and as for Toklas, her genius seemed to emerge in her caring for and love for Stein, who also bloomed under Toklas' attention. And yet I can't help but think, "Why can't she wash a dish? Why can't she turn the crank of the car?" This kind of artist, who is always cared for, is the kind that makes every arts colony experience potentially dicey. They show up, away from their support system, and look to repopulate it with you. Last year on my residencies, for example, I made an omelette for a fellow fellow who did not know how to cook an egg, I endured food theft from fellows who would not go shop to replace what they needed, I did dishes left behind in the sink because it seemed disgusting–until I remembered I hadn't taken the residency to do their dishes. I was there to do my own work.

In any case, I'm enjoying the book—it's fascinating to me to view it partly through the lens of her selfishness, to see her works as created out of it—I normally assume such selfishness precludes the ability to offer any insight at all. But then I think I suffer from one of the prejudices of my age, and perhaps a peculiarly American one, more than I might like, as, well, it drives me crazy in others. This is the belief that a writer must necessarily be a good person—or a person I have any affinity with at all—if I have an affinity with their work.

It's facile to assume that connecting to a writer's work also means you'd connect to them personally, but it is a mistake so many of us make all the time. Even worse is when you reverse it and begin to think that a writer must be a good person in order for you to read them, and by good person I mean good per the arbitrary values you personally assign to that idea of good—for example, if you feel you can't read Republicans, well, that was in fact Stein's political stripe.

In the meantime, it seems to prove, all too horribly, what I said about the "soulless careerist" in this post recently.

I've decided to re-read Alice B. Toklas What is Remembered alongside this now and comment on it as well.