Alexander Chee's Blog, page 2

October 13, 2014

The Time Out New York Fiction Issue

I have a new short story, “Life Model”, my science fiction debut, out in the Time Out New York Fiction Issue, “Best New Fiction In NYC”, on stands now. I don’t want to say anything else about it except that it was fun to write, and was written out of a prompt for Hyphen Magazine’s Litcrawl NYC event–I was sent a poem by Sally Wen Mao, and asked to write something based on that. She sent her incredible poem the Dreaming Machine, and pretty quickly I understood science fiction was the only direction I could go in. This is what came of it. Thank you to Karissa Chen at Hyphen for organizing that, and to Sally, who is a genius.

The Years of Reading Women

This weekend, I was honored to have an Author’s Note column in the New York Times Sunday Book Review’s special double issue devoted to women writers. The column, “Gender Genre”, is about some of what I learned during a period of almost three years when I stopped reading men, starting when I was 20, and came from thinking about the current crisis we are in, which is the old crisis we have been in for so very long, which is that women are not treated as human.

The idea back then came from a class I briefly describe in the column, Modernity: Gender and War, taught by the late Hope Weissman, one of my very favorite professors. Professor Weissman was a Wife of Bath expert, and also taught Chaucer, which I also took with her–even doing my paper on the Wife of Bath, which is how I discovered her expertise. There was a very grim moment during the writing of my final paper when I understood I would be citing her own work in the presentation of my ideas. The paper went well, but I would say I learned to be careful there.

I know at least a few will imagine that I was being taught the ideas of some kind of radical feminist in the lead-up to the period my column describes, and it may be a way to describe Professor Weissman, but I would say only that we were reading Paul Fussell’s The Great War and Modern Memory. In it, he describes the way the mechanization of war in World War I dismantled the conventions of Western culture, in which men were taught to fight for honor: their honor, the honor of their family, the honor of their country. To do so, they were allowed a kind of license we give to heroes even before they were heroes, as a way to get them to go and be heroes. When war was mechanized, the honor left–both surviving or dying no longer meant what it had, and so this kind of role for men was meaningless. The entire system is still in place, though it has nowhere to go. And so all of the violence it permits also has nowhere to go. Instead, we live with it, or, we try to–a machine that no longer has a purpose, or at least, no longer the purpose it once did, still making boys think they are superhuman–and women, less than human. A conveyor belt full of bright shiny toys that ends in a cement wall. I think we can say, 100 years after that war, the world still has not adapted to what happened then.

I’ll be blogging more later this week about that column and the reading I did then.

August 30, 2014

The Insincere House

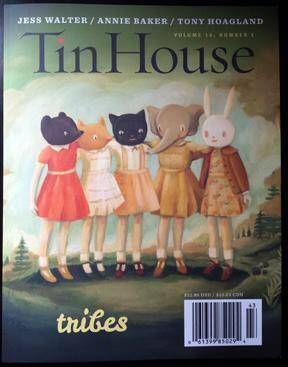

I have a new story, “The Insincere House”, in the new fall issue of Tin House.

I couldn’t be more excited. The issue features fiction and essays by some favorite writers: Jess Walter, Roxane Gay, Tayari Jones, Alice Sola Kim, Matthew Specktor–it’s amazing. And it has this beautiful cover, too.

Copies are in stores now. For a glimpse of the first page of my story, click the more button.

August 24, 2014

The Magician’s Land

I reviewed the final novel to Lev Grossman’s trilogy, The Magician’s Land, over at The Barnes and Noble Review. I loved it–it was a perfect departure from reality, which, I really needed at that point, and he does the difficult thing of finishing a trilogy well. Recommended also: reading this post from Grossman on what Fantasy novels are even for.

Recommended also also: Choire Sicha’s review over at Slate, which takes on some of the issues of the novels, and proposes a very smart, funny reading of the trilogy. A theory I will write more about soon.

Everything I Never Told You

This is an interesting historical moment for me personally: as an Amerasian writer, being able to review a debut novel about a biracial Chinese and white family, set in 1970s Ohio. The main character is a little older than I was then. I remember being treated quite often as a spectacle, as a child–a spectacle, an experiment, an oddity. Also: a freak, a family crisis. Both grandfathers did not attend my parents’ wedding. I have more to say about the novel and will either blog it here or write an essay on it, somewhere else, but for now, do consider reading this novel, it is a genuine literary thriller that tries to examine the politics of the time through the very personal lens of these characters lives.

July 22, 2014

Snowpiercer

Last Friday, my partner Dustin and I decided to get out of our apartment and go to a film in an actual theater. I chose Snowpiercer because we both love Bong Joon Ho’s other films, and so I guessed we might love this one. We went to the theater at Lincoln Center, and before the film began Dustin said to me, “I’m really glad I didn’t know anything about this film before seeing it.”

As a result, I tried to think of what I knew going in as the credits started.

I knew a few things. As I texted to a friend before I went in, “It’s the new Bong Joon Ho, but with him directing white people”. I also knew it was about a train that circles the world, after an apocalypse, and that it houses the last remnant of humanity. Also, that it stars Chris Evans, Tilda Swinton, and the amazing Kang-ho Song. But that was really it.

The film begins with the story of the apocalypse: an attempt to stave off global warming with a chemical shield seeded into the atmosphere accidentally supercools the Earth, and creates an apocalyptic ice age. We are brought into the aforementioned train, circling the frozen landscape of the planet forever, through the story of a heroically built young white man, Curtis, played by Chris Evans, obviously, who is stoically leading a revolution of some kind from within the ranks of the lowest classes of the train. Tilda Swinton is Mason, the villain, a wild-eyed martinet with false teeth and thick glasses, deputy to the train’s inventor, Wilfred. Kang-ho Song, a truly remarkable actor, and a favorite of mine from such films as Thirst and The Host, plays Namgoong Minsoo, a Korean engineer who designed the doors to the train, and the security, and thus is, quite literally, the key to Curtis’s plot to get the front of the train to deal with the rear. The revolutionaries just have to find him.

When they do, Minsoo turns out to have a price for his participation in the revolt: they must also free Yona, a young girl in the drawer next his,played by Ah-sung Ko, and he wants, for each gate he opens, a chunk of a toxic drug that is a byproduct of the engine powering the train, which seems to function like a cross between meth and opium. A chunk for him and a chunk for her. The revolutionaries are bewildered that this is what it takes–isn’t freedom enough?–but he insists, and they oblige.

Curtis’s gang of upstarts includes John Hurt as a multiple amputee soothsayer, Octavia Spencer as an aggrieved mother, her child stolen from her for mysterious purposes in the film’s first moments, and Jamie Bell, as Curtis’s lieutenant, young, impatient and entirely worshipful of Curtis. Nothing in the film, including our rag tag band of heroes, is quite as it seems–and our sense of who the heroes and the villains are will get considerably revised by the ending. Along the way, we are treated to a visual landscape that is one part Terry Gilliam’s Brazil, one part Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, and one part, well, any brutally violent Korean film about revenge.

Post-apocalyptic films are by now a kind of pornography, in which the apocalypse leads to some kind of renewal of the world, usually–just not right away. I wonder sometimes if this expectation, built into us by Christian ideas of the End Times, are part of what gives us such an appallingly relaxed attitude toward the end of the world. A kind of “don’t worry, it’ll all work out for the best” idea. It vanishes in the face of a story that literalizes the Rapture, like The Leftovers–we can see that it won’t work out, not for all of us. Maybe not for any of us.

This idea that an elite will be saved by divine intervention or something like it is very much the heart of Snowpiercer. The train, designed to be an entirely self-sufficient environment, is a remarkable invention of its own kind, including the way it pounds through ice and snow across the track and brings the water inside for the occupants. It is also, as most trains are, constructed around social class. As in any train, there is first class, business, and coach. And then the stowaways. Curtis’s group comes from this last–people saved by the beneficent inventor, Wilford, played by Ed Harris–and who are not given any rights during this awful interregnum on the train. A period that at the film’s opening, we discover, has lasted for 17 years.

After, as we left, Dustin was unsatisfied, and I was not, and so I am writing this in a sense to figure out what I think of the film. Dustin has a theory that no matter the weapons or the milieu, in any American big budget drama, the action all comes down to a brutal barfight, and this one proved him right again. Near the end, the film is a knock-down drag-out fight, occurring throughout the train, brutal and bloody, with anything being used as a weapon, as needed.

There was, interestingly, no improbable kung fu, not even from the Korean characters, Namgoong Minsoo, and his beloved, Yona, who dutifully play the role of addled drug addicts who also happen to have the secrets to the train–Minsoo from his work engineering it, and Yona, because she is clairvoyant. They are the real scene stealers, and Yona, as played by Ko, is a particularly a magnetic figure, a clairvoyant waif, born on the train and with no sense of what the world was or could be.

At a certain point, I understood the film was at least two stories–that of Namgoong Minsoo, and that of Curtis–and that in a sense they were rivals, for what would be prevail as the narrative, and who would be the hero. And that this is the reason I think I enjoyed the film, despite the hamminess Dustin complained of–this, and the sense that Bong Joon Ho was intent on taking us all the way around the way the sausage gets made, as it were, in a culture running on one of these myths about elites, apocalypse, and survival.

Without spoiling the film, I can sa then that what we see is the story of a people who are brutally suppressing another class of people in order to justify their sense that their elite status protects them from harm–they do what they do because they believe they have the right to do what they do, and they have the money and force to enact a kind of murderous theater that projects that divine status to society as a whole. These elites don’t question that it isn’t right, or that it could be different, because they desperately need to believe they are special.

I did not know that the film was an adaptation, if substantially altered from the original, of a 1982 French graphic novel, Le Transperceneige. The story it tells us, in any case, is not a story about the future, or 1982–it’s a story that is happening around us right now.

July 15, 2014

I Don’t Even

I pick this blog up again after a 4 month absence, and will begin with the usual blog apology: I’m sorry to have left this off. Especially as, time after time this year, when I have been most ambivalent about blogging, I have had people tell me how much the blog meant to them.

Where have I been? Well, a lot of places. In literal terms, I spent the spring semester teaching at the University of Texas – Austin, in their MFA program, and living on Austin’s East side as I did so. I returned to New York City with a new appreciation for brisket and kombucha on tap.

After that, I went to Boston to teach at Grub Street, then to Korea, on family business, and then gave a reading with Paul LaFarge at the Wesleyan Writers’ Conference. I am back in New York City, and will be teaching a fiction workshop at Columbia University’s MFA in writing this fall.

In a plot twist, two poems of mine have been published, after many years of not writing or at least not publishing poems. I have a new poem up over at the Awl, “I Don’t Even”. Another poem, SAINT, is in the current issue of Azalea.

I have also been doing some reviewing. specifically, I reviewed Clifford Chase’s memoir, The Tooth Fairy, for Slate, and Chris Abani’s novel, The Secret History of Las Vegas, for The Barnes and Noble Review. I interviewed Helen Oyeyemi for Buzzfeed Books.

I also published two big personal essays this spring, a long time in the making. The first, “My Parade”, about how I began as an MFA doubter, and then went to Iowa, appears in n+1′s MFA vs NYC anthology and is excerpted online in full at Buzzfeed. The second, Mr. and Mrs. B, about my time as a cater waiter for William F. Buckley, is currently print only, in Apology, vol. 3.

Looking to the future, this fall, a new short story of mine, “The Insincere House”, will appear in the next Tin House. And as for news on The Queen of the Night, I’m currently making my way through an audit of 9 changes I made to the manuscript this year, and will have scheduling news soon.

[image error] [image error]

March 13, 2014

MacGuffins

The simplest definition of a MacGuffin is that it gives the characters something to do in such a way that the plot is made around it. The term comes from the films of Alfred Hitchcock, who defined it as the mysterious object in a thriller that sets the whole story in motion. For an object in a novel to be the MacGuffin, the object must be one on which the fortunes of a character seem to rest entirely. Think Chekhov’s Gun, then, but if that gun never went off, and instead was stolen by a young man no one in the room quite remembered meeting, and so they set off to find him, and catch him before he uses it—because that gun must be returned, or all is lost. The real story and its major themes arrange themselves as the search for said object is underway. You look up from the search for the gun, and you understand something else entirely has happened. Calling it a plot device makes it seem as if it is somehow separate from the plot, something that drops the plot off at work, but it is more integral than that.

This is from my essay “Donna Tartt and the MacGuffin”, over at Tin House, in which I try to write about some of my thoughts about kinds of retrospective structure. I confined myself there to the structure of the The Goldfinch, but I had thoughts about The Secret History, too, so I thought I would put an appendix to the essay here for the interested.

Francis Abernathy from The Secret History has a cameo in The Goldfinch. He appears at a party in New York, and you hear Theo get introduced to him and Theo acknowledge him—they already know each other. It was a sweet Easter Egg to fans, and I like the idea of Tartt’s novels as belonging to a single world, though it feels to me more like Theo and Francis are in adjoining rooms in some massive hotel in Tartt’s mind.

This novel really a very different suite of rooms.

If you haven’t read The Secret History, and you fear spoilers, turn back now.

When I began reading The Goldfinch last summer, it more or less interrupted my year of reading Iris Murdoch. I have as yet unproven theory of Tartt as an heir to Iris Murdoch, who was one of her idols. Murdoch had magnificent MacGuffins, they were like Hippogriffs, really, and she had tremendous style as a writer also. Tartt isn’t as philosophically minded, but I think she is fascinated by fate in the way Iris was.

The Secret History has a MacGuffin also, a fairly conventional one: the murder at the novel’s heart, announced in the prologue along with the guilt of the narrator, Richard Papen. But what she does with it is the opposite of what we see in murder mysteries. The hunt for the murderer is what would normally be the chase. Instead, what we see is the gradual realization, on the part of the murderers, that what they did is untenable. So the first section after the prologue introduces Richard and how he found his way to college, how he was inducted into a clique of Classics students on campus and in the process, became the perfect person for Henry, the murderer in chief of that group, to use for his purposes. Richard first feels inducted, special, chosen—and then discovers he is special, to the extent that he can only go forward with the plan Henry has for them, including the murder, not knowing he is meant to be the patsy.

After the first half makes its way to the murder, the second runs from it, to the end.

In each half–and the novel is almost perfectly bisected–the narrator is always on the outside of the next part of the mystery before then being brought into the inside of it, where he finds the next mystery, and so on, until he reaches the very sad endgame, the destruction, more or less, of the group’s fates. In the first half, the murderers’ victim, their mutual friend Bunny, seems insufferable, such that we are nearly rooting for him to at least suffer some come-uppance. In the second, though, the full horror of what’s been done to him, and the truth of Bunny’s humanity, descends into the novel with his death, and the realization that none of them really will be spared, even if they are never discovered by ‘authorities’, arrives. They haven’t just killed Bunny–they’ve ruined themselves too. Given the murder is known from the beginning, the suspense is in watching to see how they’ll survive it, if they do at all. We know that Richard, the narrator, survives, as the keeper of the story, as all narrators have the misfortune of doing. The Prologue is the gate, Part I is the leadup, Part II is the lead-away, and the Epilogue takes us into the afterlife, in Henry’s case, quite literally.

At each moment, Tartt tells us something that is coming, and then how it happened, and each event trades off to a new one, but she disguises this in shaggy conversations about the classics, art, life, drugs, sex, money, and class, all of which eventually reveal themselves to have been the more or less concise corridors you didn’t know you were traveling, into the sharp turns of the plot. Even the dreams of Bunny and Henry are beautiful, and perfectly handled, with Henry’s presence in the dream at the end being sublime, as ending and dream both.

Was it a literary thriller then? It was, to the extent that ‘literary’ is defined as producing insight into the human condition. The mystery was how you could convince yourself you could commit a murder and live with yourself afterward—and then, how you would not.

In both novels, however, we are with the character who took the missing thing. We are having this story from the point of view of the MacGuffin.

February 25, 2014

#AmtrakResidency

Every now and then you get to change the world.

Thanks to everyone who helped make the noise that made this happen. You’re amazing. I’ll be telling my own story on this soon. But for now, just thank you.

October 18, 2013

Moonlit Dance

I am visiting my mom in Portland, Maine this weekend. We had a beautiful dinner at Fore Street and then we went to the Portland Museum of Art, where I saw the beautiful old paintings I grew up with on my visits there–the Winslow Homers, the NC and Andrew Wyeth paintings, the Sargents. It was consoling, strangely. I have a recurring dream I haven’t had in a while, in which I am in my mother’s house, but it is some vast place, with libraries that go down several floors, and people living in the stacks. The museum’s exhibits had the feeling of being like a forgotten wing of the house from that dream.

I fell in love with a new painting, or, new to me. Edward Steichen’s Moonlight Dance, Voulangis, 1909. And then we hid from the terrible modern things in the Winslow Homer wing, before finally leaving, though I stopped off to get two postcards, and four moustache-shaped erasers (Winslow Homer’s moustache, of course).

I got a little lost driving back but we didn’t mind because the moon was so beautiful. We wound up by Mercy Hospital. Did you hear about the seal, my mom said.

No, I said.

He came up out of the ocean there, pointing past the far lane on the left, to the water. And then he walked up in the snow to the hospital.

I turned the car around in the hospital driveway.

Did he know someone there, I asked, and she laughed, and we drove home.

When I post again, we’ll be back to the topic of Iris Murdoch.