Tim Matthews's Blog, page 7

September 21, 2015

Startup Marketing Essentials: #9 Establishing a Testing Culture

You can’t work in a startup these days without doing A/B testing. Multivariate if you are really good. There’s a reason why Optimizely is spreading like digital kudzu. But you can’t just buy software. You need to make testing part of your culture. Here’s how. – TM

A/B testing is en vogue. Everyone’s doing it, or at least taking about it. Putting it into practice requires more than talk and tools, though. You need to create a testing culture to really make it work.

A/B testing is en vogue. Everyone’s doing it, or at least taking about it. Putting it into practice requires more than talk and tools, though. You need to create a testing culture to really make it work.

For those who are unfamiliar with A/B testing, welcome to the party. The idea is simple: test out two variations: A and B. Pick the winner – sometimes called the champion – and go with it. Then do it again, aka iterate. The champion is the new A, and you create a challenger B. And so on until you reach the point of diminishing returns and move on to something else to test, e.g., your signup forms rather than your email subject lines. A more advanced form is called multivariate testing, where you are testing combinations of multiple A’s and B’s at the same time. (I could geek out all day on A/B testing, but I’m going to leave it at that for now. If you want to learn more on testing and measurement, I wrote a more detailed piece you can find here.)

A/B testing is actually quite old. So it’s more accurate to say it’s back in fashion. Direct marketing greats like Les Wunderman perfected the art through the 1950’s and 60’s. It’s really effective, and I’m happy to see it so popular again. Because it works.

So, back to the culture. A dirty little secret about A/B testing is that it’s a lot of work. At least double for everything you do, and even more when you think about all the data collection and measurement required to make it work. And what happens when you ask people to do things that require more work? (Just exercise five days a week and you will lose weight!) They don’t do them. Or, they get discouraged because it doesn’t work. Or both.

To avoid these pitfalls, you need to establish testing as a part of you culture. You need to lead the way and require your people have conversations based on data and results rather than opinion. You need to change the mindset from task completion to continuous improvement. Here are a few techniques I found useful in making this shift in my organization.

Set metrics for everything – Yes, everything. Not just conversions. What type of content is read more? Do videos get more views on YouTube or Wistia? Helicopters or T-shirts as giveaways at trade shows? Now, I know what you are thinking. More metrics means more toil means you will just burn people out. Quite the opposite. It will empower them with data. We’re not doing helicopters at the hackathon, Tim. T-shirts pull 37 percent better…In other words, arming employees with data allows them to stop doing busywork or wasting time on projects that don’t move the needle.

Test, test, test – You are never done. This can be demotivating, so be careful. You may reach the limits – go asymptotic (How’s that for high school math recall?) – of certain tests. Rather than going for that last 0.001 percent gain, try something else.

Encourage experiments – Marketers like to do cool new stuff. Experiments can be fun (Okay, I admit, you may need to work on the art and English majors on your team.). But let people know they can try out cool new stuff. If it works, great. If not, good for trying (more on that next).

Establish a safe zone – It’s okay to fail. This is key. Experiments fail. Scientists fail on their way to great discoveries. You often learn something from a failure, or at least you debunk something that was assumed to be true. Culturally, you need to let people know you’d rather have them fail on two experiments on the way to one great one, than not try at all. (I think I’ve channeled both my mom and Teddy Roosevelt here, but you get the point.) You may find this more challenging than you expect. Marketing folks, in my experience, are more likely to exaggerate their accomplishments, and may be uncomfortable admitting failure.

Encourage employees to speak or blog about their tests – The great thing about testing is that you have data. And data makes you an expert! Okay, maybe not an expert, but it is a vehicle to share ones expertise. Encourage your employees to speak at meetups and blog about their experiments. You will be helping them develop their careers, which is also part of your job

Train employees to know what questions you will ask – This last one is my favorite. Get your voice in their head. What would Tim ask? You want your employees to challenge their own assumptions and results. After a while, you will find employees have answers to everything you ask. They may even finish your sentences.

There’s a reason A/B testing is all the rage. It works really well and can be a very effective marketing weapon against your (lazier) competition. So if you are not doing it, time to start. Just keep your people in mind as you do.

Have a cultural tip to share? Or maybe a better headline to challenge the one at the top of this post? Let me know. I’d love to hear from you.

Tim Matthews is the VP of Marketing at Incapsula and author of The Professional Marketer. His thoughts on marketing can be found in his blog Matthews on Marketing.

September 14, 2015

Startup Essentials #8: Lead Nurturing and Progressive Profiling

Leads are the lifeblood of a startup. One common mistake made by startup marketing teams is ignoring leads that are not ready to pass to sales. These leads need to be nurtured – helped along – until they are ready. If you ignore them, you have wasted the money you spent to acquire them in the first place, and paying yet again for brand new leads that may or may not be more qualified. And as you nurture your leads, you can learn more about them, using what’s known as progressive profiling. – TM

Leads are the lifeblood of a startup. One common mistake made by startup marketing teams is ignoring leads that are not ready to pass to sales. These leads need to be nurtured – helped along – until they are ready. If you ignore them, you have wasted the money you spent to acquire them in the first place, and paying yet again for brand new leads that may or may not be more qualified. And as you nurture your leads, you can learn more about them, using what’s known as progressive profiling. – TM

Lead Nurturing

So what happens when a prospective buyer fits the profile and has expressed some interest, but is not ready to buy? Maybe he or she made an inquiry or two, looked at some of your collateral, but doesn’t have the money or budget to make the purchase and is not sure when he or she will. If you are using lead scoring, perhaps the score did not meet the MQL hand-off threshold. Or, maybe sales accepted the lead, but when they qualified further and realized the buyer was not ready, did not convert to an SQL.

Since you have already paid money for the lead—the total cost of acquiring the name, any asset printing and mailing costs, and the time of your telemarketer and salesperson—doing nothing would be a waste. Yet many companies do just this. They go out and buy a whole new set of names and start the process all over again. This approach is both inefficient and very expensive.

This is where lead nurturing comes in. Lead nurturing is a systematic process for moving leads to the next state. Nurturing is typically aimed at moving names or one-time inquirers to the MQL stage, but can also be used to drive interest in additional purchases with your installed base of customers.

What distinguishes nurturing from other marketing programs is that it is sustained. Nurturing has been around for decades in an informal fashion. Salespeople making periodic calls to prospective customers they have met but not sold to is very common. More modern nurturing uses marketing automation software to systematize the process, and better target leads with offers designed to appeal specifically to them.

In his book The Leaky Funnel, Hugh Macfarlane adds to the funnel metaphor and describes a more realistic version. At each stage of the funnel, customers drop, or “leak,” out. Imagine the funnel with multiple holes in the side, with leads leaking out all over the place, but for different reasons. Some customers do not have the budget. Others were looking for a particular feature that you do not have. Maybe your price was too high. There are any number of reasons a buyer would leak out and not move down to the next stage.

Highly effective marketing departments segment the leads that fall out by reason and aim their nurturing at those reasons. Prospects who fell out because they were looking for a certain feature, for example, should be sent an e-mail when your product adds that feature. If a new price promotion or pricing scheme becomes available, prospects who fit the profile but fell out for budget or affordability reasons should be targeted. You might send a glowing product review to prospects that researched but did not seriously consider your product.

Creating a lead-nurturing database can be facilitated by lead scoring. Leads with scores below the MQL hand-off threshold can automatically be added. Leads that drop or leak from the funnel should also be added, along with a code or label that indicates the reason.

Progressive Profiling

The process of collecting information about contacts over a period of time is called progressive profiling. The more information your company has for a contact, the better you will be able to target that individual.

One cardinal sin marketers commit is asking prospects too many questions at one time. Doing so will cause them to get annoyed with a telemarketing or sales rep on the phone, and it will likely discourage them from filling out a lead capture form, known as “form abandonment.” In fact, research conducted by MarketingSherpa has consistently revealed that prospective customers fail to complete 60 percent of registration forms, with form length being a major factor.

So, how should you approach progressive profiling? To begin with, in the first interaction, you should request only the essential pieces of information—somewhere between three and five. If you are capturing leads via the web, then you should ask for only the information you need for your next step. For example, name and e-mail address should be sufficient to add these leads to an e-mail nurturing program. Alternatively, you would request a phone number if the next step is to have a telemarketing rep call them.

After you have established contact with prospective customers and elicited their basic information, you can get additional information with subsequent marketing activities. When you send prospects a nurturing e-mail, make certain to add a few additional fields for them to complete—for example, information about their titles, roles, and responsibilities could be useful to a B2B salesperson. Really good marketers make the answers relevant to the offer, in effect customizing the offer based on their responses. In this way, the contacts see value in providing additional information. As an example, you might ask prospects how big their company is and which industry it operates in so that you can send them a customized version of a report your team produced. Creating this type of customizable asset requires a bit more effort, but the continued contact engagement and the reduction in abandonment this extra step generates are worth the effort.

Most modern marketing automation systems include built-in tools for progressive profiling. They automate the request for additional information based on the information that is already contained in the database record for that prospect, or what particular offer is being made to the contact. Progressive profiling still requires up-front planning about the lead flow, a bit more work on automation, and potentially consideration during asset creation.

Startup Essentials is a series of excerpts from The Professional Marketer . I’ve pulled out what I think are the most essential skills a founder or a marketer at a startup would need.

September 9, 2015

Startup Marketing Essentials: #7 How to Build a Great Website

Every startup needs a website. I’m stating the obvious. So I’ll restate. Every successful startup needs a great website that meets its business goals: awareness, reach, virality, conversion. Building (or rebuilding) the right one takes a lot of effort. Here are some pointers on how you should conceive and plan your site. – TM

It’s funny to think that the web, which hundreds of millions of people use every day for shopping, dating, gaming, news, and socializing, began as a technology to help improve, of all things, physics research—a topic of interest to only a fraction of the world’s population. Yet today, the web is huge. According to What Technology Wants by Kevin Kelly, himself a chronicler of the early days of the web, it holds more than a trillion pages.

It’s funny to think that the web, which hundreds of millions of people use every day for shopping, dating, gaming, news, and socializing, began as a technology to help improve, of all things, physics research—a topic of interest to only a fraction of the world’s population. Yet today, the web is huge. According to What Technology Wants by Kevin Kelly, himself a chronicler of the early days of the web, it holds more than a trillion pages.

Twenty-plus years since the first website was created by physics researcher Tim Berners-Lee (since knighted by the Queen of England) at the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) in 1991, we are already several generations away from its original Spartan black text with blue hyperlinks on a white page. We’ve moved from professional design to rich media and animation, to social media inclusion, to the requirement of usability and availability on mobile devices. All of these innovations been driven by the insatiable consumer demand for web content and the critical role the web has assumed in modern business.

With the amount of time consumers spend online and the use of the web by businesses searching for partners and suppliers, the web has become a vital marketing tool. A well-constructed website has been transformed from merely expected to an indispensable mechanism for product differentiation and competitive advantage. Despite the centrality of the web in both our business and our personal lives, however, many marketing teams are not truly optimizing their websites.

This post will lay out the process for developing a new website from scratch, starting with the establishment of website goals and moving through the primary considerations of usability, design, and content.

Establishing Website Goals

The initial step in utilizing the web as a marketing tool is, of course, to create a viable website. Before you undertake any development work on the site, however, you need to identify the site’s primary goals. Is the site intended to educate, inform, entertain, sell a product, or some combination of these? The goals, along with the target audience, will determine the site’s functionality, design, and content. Sharing these goals with the web team, management, and rank-and-file employees will help avoid any number of artistic and functional arguments, as well as increase the likelihood that the project will be a success. You should also involve customers and partners in the process if possible—the site is intended for them, after all.

To clearly define your needs, goals, and objectives, you should ask yourself a few detailed questions:

What are your primary business objectives, and how can the website help you achieve them?

Who will use your website, and what are their tasks and goals?

What information and functions do your users need, and in what form do they need them?

How do users think your website should work?

What hardware and software will the majority of people use to access your site? Will they be using a laptop, a tablet, a smartphone, or some combination of these tools?

Site Fundamentals – Usability, Design, and Content

After you have agreement on your goals, you are ready to begin work on the three fundamental aspects of your site: usability, design, and content.

Usability

Usability measures the quality of a user’s experience when interacting with a product or system—whether a website, a software application, mobile technology, or any user-operated device. In general, usability refers to how well individuals can use a product to achieve their goals and how satisfied they are with that process. As it relates specifically to the web, usability is the measure of the quality of customers’ experiences when they interact with your website.

Usability is a combination of several factors:

Ease of learning – How fast can a user who has no previous experience with the website learn it sufficiently well to accomplish basic tasks?

Efficiency of use – Once experienced users have learned to use the website, how fast can they accomplish tasks? A site that is efficient to use will likely bring users back. This tendency, along with the quality of the content, will help achieve what web developers call “stickiness,” meaning the amount of time users spend on a site and the likelihood they will return.

Memorability – If users have visited the website before, can they remember its setup and functions well enough to use it effectively the next time? Or, do they have to start all over again and relearn everything? When users must remember information on one web page for use on another, they can remember only about three or four items for a few seconds.

Performance – No matter how intuitive or efficient the site is to navigate, poor performance is a killer. A site’s performance can be affected by the servers and network that host it, the network of the user, and the content on the site. Users become frustrated if a web page does not load immediately. A study by KISSmetrics showed that 25 percent of users abandoned a website after waiting just four seconds, and the majority of mobile users would abandon a site after ten seconds. In the same study, KISSmetrics found that every additional second of load time reduces conversions by 7 percent. When designing a new site, or augmenting an existing one, always test the performance to make sure the combination of content and a typical user’s network speed does not cause slowdowns.

Design

The design of a website must support usability. In addition, the site is an expression of your brand, so its design should reflect your identity. Keep in mind that users will make an immediate judgment when they view your site, unconsciously assessing whether it is trustworthy, welcoming, relevant, and professional. Your design should support the image you want to portray.

Below are specific design considerations for the different parts of a website.

Home Page

A home page should concisely communicate the site’s purpose, and it should clearly indicate all of the major options available on the site. Generally, on latop and desktop screens, the bulk of the home page should be visible in a single screen or “above the fold”—a term borrowed from newspaper publishers meaning the top half of a folded newspaper—and it should contain a limited amount of text. Content you want all visitors to see must be placed above the fold.

Designers should provide easy access to the home page from every page in the site so users can get back to where they started. The first action of most users is to scan the home page for link titles and major headings. Requiring users to read large amounts of text can slow them considerably. Some readers will avoid reading it altogether.

Navigation

Navigation refers to the methods people use to get to information within a website. A site’s navigation scheme and features should enable users to find and access information effectively and efficiently. Create a common site-wide navigational scheme to help users learn and understand the structure of the site. Use the same scheme on all pages by consistently locating tabs, headings, and lists. Many users expect to find a site map—a kind of table of contents—in the footer of the page. Locate critical navigation elements in places that will suggest “clickability.” For example, lists of words placed in the left or right panels are generally assumed to be links. Also, don’t get too cute with the words in the navigation. Your goal should be comprehension, not originality.

Lastly, users expect to be able to search within a site to find what they need. Make sure to provide this capability. A search box should be located in the top right corner of the home page and subpages.

Subpage Layout

Subpages are pages that are one level down from the home page. They are sometimes called second-level pages, with the home page being the top-level page.

Well-designed headings make it easier for users to scan and read written material. Designers should strive to create unique and descriptive headings and to incorporate as many headings as is necessary to enable users to find what they are looking for. Headings should provide strong cues that orient users and inform them about page organization and structure. Headings also help classify information on a page. Each heading should be helpful in finding the desired target.

On long pages, include a list of contents with links that take users to the corresponding content farther down the page. Also, provide feedback to let users know where they are in the site. A common method to accomplish this goal is to insert breadcrumbs —horizontally arranged text at the top of the page, above the headline, that tells users where they are in the site’s navigation and helps them find their way back “home.”

A well-designed website will enable users to access important content from more than one link. Establishing multiple paths to access the same information can help users locate what they need. When you’re designing the site, always remember that different users will try different approaches to finding information and may also search for information using different terms.

One fundamental rule for a user-friendly design is to display a series of related items in a vertical list rather than as continuous text. A well-organized vertical list format (e.g., bullets or grids) is much easier to scan than horizontal text, whether prose or a list.

Finally, your site’s graphics should add value to and increase the clarity of the information contained on the site. Relevant pictures are often more powerful than labels in compelling a user to take a desired action.

Alt Text

Another basic design rule is to use text equivalents for all nontext elements, including images, graphical representations of text and symbols, image map regions, animations (e.g., animated GIFs), sounds, audio files, and video. Text equivalents are referred to as alt text, or alt tags, and are useful for search engine optimization as well as usability. Users will often hover their pointer over an image to read the alt text.

Content

Content is simply the information provided on a website. For a website to achieve its goals, the content needs to be engaging, relevant, and appropriate to the audience. Below are a few fundamental rules for selecting and creating useful content:

Clear language – When you are preparing prose content for a website, use familiar words, and avoid the use of jargon, just as you would for good marketing collateral. If you must use acronyms and abbreviations, make certain they are defined on the page in language that typical users will understand. Shorten for readability—minimize the number of words in a sentence and the number of sentences in a paragraph. Make the first sentence of each paragraph descriptive of the remainder of the paragraph. Write in an affirmative, active voice. Limit the amount of prose on each page.

Prioritize – Putting critical information near the top of the site and ensure that all necessary information is available without slowing down the user with unneeded information.

Build for scanning – People scan before they read, so structure each page to facilitate scanning. Use clear, well-located headings; short phrases and sentences; and small, readable paragraphs. Again, use bulleted lists or grids where appropriate.

Group – Make certain to group together all of the information that is related to a topic. This system minimizes the need for users to search or scan the site for related information. Users will assume that items that are placed in close spatial proximity, or that share the same background color, belong together conceptually.

Visual aids –Tables, graphics, and other visuals are great for aiding understanding. Make sure to pick the best one. Presenting quantitative information in a table (rather than as a graph), for example, makes it easier to read the numbers themselves. Presenting it as a graph illustrates trends or relative size. Usability testing can help you determine when users will benefit from using graphs, tables, or other visualizations.

Less is more – Do not overload pages or interactions with extraneous information. Displaying too much information can overwhelm users and hinder their ability to assimilate the information they need. Help users focus on their desired tasks by excluding information that task analysis and usability testing indicate is not relevant.

Once you’ve got all this planning done, it’s on to wireframes and the fun work of development. You will no doubt need to add in all kinds of tools and utilities to help you manage and measure your site – from Google Analytics to Marketo to Optimizely and beyond. Putting these in place early can make like easier as you grow.

Startup Essentials is a series of excerpts from The Professional Marketer . I’ve pulled out what I think are the most essential skills a founder or a marketer at a startup would need.

September 7, 2015

Marketingspeak: What is Parallax?

You’ve probably seen a parallax website before. Especially common on long, single-page scrolling sites, images in the background seem to scroll at a different speed than the text or images in the foreground. That’s called parallax.

You’ve probably seen a parallax website before. Especially common on long, single-page scrolling sites, images in the background seem to scroll at a different speed than the text or images in the foreground. That’s called parallax.

According to web design site Awwwards:

The parallax effect uses multiple backgrounds which seem to move at different speeds to create a sensation of depth (creating a faux-3D effect) and an interesting browsing experience.

They have some great examples.

Since, as you know, I like to dig into the history of marketing verbiage, parallax comes from the Greek parallaxis, meaning “alteration.” Parallax is a difference in the apparent position of an object viewed along two different lines of sight, and is used in various fields. Astronomers use it to measure distance between stars. Rifle scope need to account for parallax to overcome differences in how a shooter perceives the crosshairs (foreground) and target (background). Video game developers use it to create a sensation of depth in first person games. And more.

August 31, 2015

Startup Marketing Essentials: #6 How to Write a Press Release

The workhorse of public relations is the press release. Written in the form of a conventional news story, a press release alerts the media to an organization’s news and presents it in that organization’s point of view. Editors and reporters use facts, quotes, and other information contained in releases to flesh out their stories. Blogs are great, but if you are really going to grow, you need to know how to write a good press release. – TM

There is a standard structure for press releases. Your company will still need to create news and find an interesting angle, but using the standard format assures you have everything the media will need. In this section, we examine the basic elements of the standard release structure.

Identifier – When creating a release, you should place the words “PRESS RELEASE,” in all caps, bolded, at the top of the first page. Though this might seem obvious, how is an editor or reporter to know what the document you or your agency sent them is? Significantly, organizations also release a standard PR document called a media alert to invite or alert media representatives to an upcoming event, such as a press conference. A media alert contains many of the same elements as a press release, so people can confuse the two. The “PRESS RELEASE” label clearly distinguishes your news from a media alert.

Timing – Press releases typically state “For Immediate Release” at the top left, bolded. This statement informs editors that the story is publicly available—on the wire or via your website—and that they can report it. If your story will be released at a future date, then the press release should say “For Release on [fill in your date].” Organizations use this approach when they give releases to the media in advance of the public release date—a common practice. If you want to make the point more strongly, you can substitute “Embargoed until [fill in your date].” Even if you do label a release as embargoed, it is best to have a conversation beforehand with the journalists to ensure they understand and will honor the embargo.

Contact information – The contact information informs the reporters and editors who supplied the story and whom they should contact if they have questions. This information should be right justified and placed above your headline, with the word “Contact” in bold situated directly above it. Include the contact’s name, company, phone number, and e-mail address. If you use an agency, the contact may be someone from the agency. In some cases, press releases include both the agency and issuing company’s press contact information. Generally, the company contact should not be your spokesperson. Rather, you should list either the PR manager or the marketing person responsible for the announcement, because you may not want the press to contact the spokesperson before he or she has been properly prepared.

Headline – Just as in a newspaper or magazine, the release should contain a headline that grabs the editors’ attention and spurs them to continue reading. Moreover, because the release will live on long after the story appears on your website, the headline should also draw in the average reader. Headlines are typically printed in bold type, sometimes in a larger font than the rest of the release.

Subhead – The subhead gives you a chance to flesh out your angle and further hook the reader. It may offer additional details, substantiate a claim, or underscore an achievement. Subheads should be printed in a smaller font than the headline, and they are sometimes italicized to distinguish them from the headline.

Dateline – In the United States, the dateline should include the city, state, and date of the press release, followed by either two dashes or an em dash. For example, a release would start “San Francisco, CA, October 31, 2013 –.” If an announcement is made at an industry event, it is common practice to include the city and state where the event is taking place. Outside of the United States, common practice is to use city and country, and sometimes simply the city if it is well-known.

The lead – The first paragraph is known as the lead paragraph, or simply the lead. In the United States it is sometimes spelled “lede,” supposedly to distinguish it from the heavy metal lead type used by typesetters, though there is much debate about the reason for this spelling. The lead should capture the entire story as if the rest of the press release were not there. It essentially serves two key purposes. First, it draws the editor, reporter, or reader further into the story. Second, in the case of what is known as a news lead, it provides journalists with the five Ws and the H: who, what, when, where, why, and how. Journalists are trained to include this information in the leads to their news stories, so you will be giving them exactly what they need. The press release is, after all, packaged news and a tool you use to inform editors and reporters. A feature lead is written in a similar style to the lead of a feature article in a magazine or newspaper, and it may set the scene or tug on emotions. It serves to draw the editor in, but it does not need to contain the hard news elements of the news lead.

Here are two fashion industry examples pulled from PR Newswire, one a news lead and one a feature lead:

BURLINGTON, Vt., Nov. 15, 2012 /PRNewswire/ – Burton Snowboards and Mountain Dew today announce the arrival of the new 2013 Green Mountain Project outerwear collection, which utilizes sustainable fabric made from recycled plastic bottles, now available in stores worldwide.

In this news lead, Burton Snowboards and Mountain Dew (who) are announcing that their new product, 2013 Green Mountain Project outerwear (what), is today (when) available in stores worldwide (where), and that the line is made from sustainable fabric (why).

BEVERLY HILLS, Calif., Nov. 27, 2012 /PRNewswire/ – At 24, many young women are just starting to figure out where they’re going in life. But 24-year-old Evelyn Fox has never been one to follow the crowd. Instead, the trendsetter is helming her own successful high-end fashion company, Crystal Heels™ (http://crystalheels.com) – and it all started with a pair of Louboutins, a couple thousand Swarovski crystals, and a heady mix of creativity and passion.

This feature lead is written in the style of a feature article and is very different from the news lead above. There is no hard news, but it does draw you into Evelyn Fox’s story.

The body – The body is the continuation of the story. After you have provided the details for hard news or set the stage with a feature lead, you should continue with additional details or explanations. The body should also contain quotes from an executive at your organization, a partner if you are announcing a joint venture or project, a customer, and/or an industry expert. It can also include headings if they make the press release easier to read. A common section in product announcement press releases is the “Pricing and Availability” heading, followed by details of when a product will actually ship, where it can be bought, and how much it costs.

Boilerplate – The boilerplate is a description of your company or organization that is designed to be used over and over without change. It supplies the editor with additional information about the newsmaker. The boilerplate should be preceded by the words “About [your company name],” and it should be limited to a single paragraph of no more than roughly a hundred words. The boilerplate should also include the URL for your organization’s website. Twitter handles are becoming increasingly common in boilerplates.

Ending – To indicate the end of the release, type “END” or “###,” centered below the boilerplate.

Here’s a picture to give you a sense of where everything goes.

Standard press release format

Photos, images, videos, B-roll – Because the press release is meant to be a packaged news story, don’t forget to include all of the elements that a magazine, website, newspaper, or television reporter might need to complete the story. These elements include photographs of the new executive whose appointment you just announced, images or technical diagrams of the new product you just announced, and videos that illustrate how the product works. You can even consider a B-roll—supplemental or alternate footage intercut with the main shot in a televised interview or news segment. B-roll can be anything pertinent to your organization, such as footage of your manufacturing assembly line, your automobiles on the test track, consumers using your smartphone or computer, your bond trading floor, or any number of other examples. The easiest way to supply these elements is to provide a URL to a web page containing all of the relevant materials.

Social media links – If you want readers of your online press release—on your website, for example—to share it with others and generally promote it, you can include links in the release that let them do so. A number of social media companies provide tools that enable you to embed these capabilities directly into your press release.

Although a press release should include all of these elements, it should never exceed five hundred words. Like a news story, the release should place most of the news up top, supported by the details in the paragraphs following the headline and lead. It should be composed in a basic font, double-spaced with wide margins and page numbers. Using company letterhead is a nice touch, but it is not required.

In terms of style, pick a news style guide, such as the Associated Press Stylebook or The New York Times Manual of Style and Usage. Use plainspoken language. Most importantly, avoid hyperbole and puffery, because they detract from the legitimacy of your news.

It is possible that you will obtain coverage if you don’t use this structure, but your odds are greater if you present your news in a format that is familiar to editors and reporters. In addition, adopting the preferred format will make your organization appear more professional and worthy of attention.

Startup Essentials is a series of excerpts from The Professional Marketer . I’ve pulled out what I think are the most essential skills a founder or a marketer at a startup would need.

____

“Boiler plate” originally referred to the small metal plate that identified the builder of a steam boiler. The term was borrowed by the printing industry, where plates of text for widespread reproduction, such as advertisements or syndicated columns, were cast or stamped in steel (instead of the much softer and less durable lead alloys used otherwise) ready for the printing press and distributed to newspapers around the United States. They came to be known as “boilerplates.”

August 25, 2015

Startup MarketingEssentials: #5 How to Build a Funnel Model

How many leads do you need, exactly? Don’t know? It all starts with the funnel model. If you are in a startup and your product is ready to sell, you need to model your sales process to understand how much to invest in your sales team and marketing budget. The model also acts as a set of guideposts that will let you know if you are on track to hit your numbers. Learn how to reverse calculate from your revenue target back up through the funnel to visitors on your website. – TM

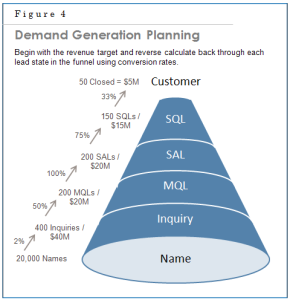

To effectively drive demand for a business, the marketing organization must have a concrete target number of leads in each state. The easiest way to calculate these numbers is to start with your revenue target and then work backward up the funnel. Using known or estimated conversion rates and the average sale size, you will reverse calculate how many sales accepted leads (SALs) and sales qualified leads (SQLs) you need to produce the required number of customers. Likewise, you will calculate how many marketing qualified leads (MQLs) you need to generate the required number of SQLs, and how many inquiries you need to produce your target number of MQLs.

There is an additional important consideration. Make certain you understand how much new revenue marketing is responsible for generating. Marketing is often not responsible for generating 100 percent of qualified leads. For example, if an organization’s revenue includes recurring annual fees, such as support and maintenance for software, or subscription renewals for telecommunications services, then sales or customer service may be responsible for handling this, and they probably will not require marketing assistance for demand generation (unless there is an attrition problem, in which case a marketing program aimed at retention will be needed).

If you work with a dedicated direct sales force, sales management typically will assume responsibility for generating 15 to 50 percent of the pipeline. These leads are sometimes referred to as sales-generated leads, or SGLs. This pipeline comes from repeat business from existing customers, pipeline carried over from previous quarters, or a desire on the part of sales leadership to make their salespeople prospect for new business. If you don’t have a dedicated sales force, then you may be expected to generate 100 percent of the pipeline.

After you have established your revenue target and percentage of qualified leads marketing needs to generate, you can start your calculations. If you do not have historical conversion data to rely on, you can obtain conversion rates from a number of marketing research firms, including SiriusDecisions and Forrester Research.

Let’s say you have a new revenue target of $10 million. Sales will take responsibility for half of this amount from the existing pipeline and by prospecting from their own contacts. So, marketing needs to generate the other half, or $5 million. To keep the math simple, our product will sell for the nonnegotiable price of $100,000. The funnel figure below illustrates our process. I’ve flipped the funnel upside down to emphasize the reverse process I use.

There are six steps to demand generation planning:

Step 1: Start with our target of $5 million.

Step 2: Divide this total by the price of an individual product ($100,000) to determine the number of customers we need. 5,000,000 ÷ 100,000 = 50 closed opportunities.

Step 3: Calculate the total number of opportunities, or SQLs, we need to generate fifty closed opportunities. Our reps believe they can close one out of every three deals. Thus, 50 × 3 = 150 SQLs.

Step 4: Calculate the number of MQLs needed to provide sales with 150 SQLs. Having worked with this team for a while, we know that sales accepts all of our MQLs. So, the number of SALs and MQLs will be the same. We also know that sales qualifies approximately three in every four MQLs (75 percent). 150 ÷ 0.75 = 200. So, we need 200 MQLs to generate 150 SQLs.

Step 5: We have to determine how many inquiries we need to produce two hundred MQLs. We know that about 50 percent of our inquiries convert to MQLs. 200 ÷ 0.50 = 400. So, we need four hundred inquiries.

Step 6: Our final step—and potentially the most discouraging—is to factor in the response rate for direct e-mail. In our case, this rate is 2 percent. 400 ÷ 0.02 = 20,000. Thus, to obtain four hundred inquiries, we need twenty thousand names.

The best sources for data on conversion percentages are your market nous, results from prior activities, your sales team, and firms that track these statistics by surveying sales and marketing teams, such as SiriusDecisions and MarketingSherpa. Make sure to be a realist and not a Pollyanna. Your sales price should be your average sales price—reflecting typical discounts, not your suggested list price. When in doubt, be conservative by picking lower conversion rates. Keep in mind that conversion rates are usually much higher for existing customers, so treat them well and market new products to them whenever you can. If your CFO wants to know why marketing needs so much money, show him or her the funnel, and explain the costs associated with buying or acquiring twenty thousand names.

Finally, make certain you have enough opportunities to achieve your revenue number. Marketers refer to the required ratio of opportunities to target revenue as pipeline coverage. A coverage ratio of 3:1 is typical (this is why we multiplied closed opportunities by three in step 3 above). Consequently, when you run a “pipeline coverage report,” which you should pull from your marketing automation system on a regular basis, a ratio of 2:1 would not provide sufficient coverage to achieve your number, whereas 4:1 would provide more than you need. When the coverage is too low, you should invest additional money to raise the number until you achieve your target. Conversely, when the coverage is too high, then you should consider allocating a greater share of your budget to other marketing activities (or, you can suggest raising the revenue forecast).

Startup Essentials is a series of excerpts from The Professional Marketer . I’ve pulled out what I think are the most essential skills a founder or a marketer at a startup would need.

August 17, 2015

Startup Marketing Essentials: #4 How to Create a Killer Presentation

Many presentations are, well, not good. If you want to stand out among the other startups and gain more press attention, buzz, investor dollars, and early customers, good presentations can help a lot. And I’m not impressed by war stories about busy execs to create their slides ‘in the cab from the airport.’ Chances are their audience could tell. Do yourself a favor and put in some real prep time and practice. – TM

Presentations are used in every marketing program. Your CEO may burnish your brand at an industry conference as part of your reputation programs. Webcasts may be a critical part of your demand generation, and your field sales force may need to learn the company pitch as part of sales enablement. Presentations are used all the time by analyst relations teams as part of market intelligence programs. But for as important as they are, why are there so many bad ones? Think about it—how often have you been utterly bored to tears watching someone drone on, or annoyed when a presenter tries to jam a hundred-slide presentation into thirty minutes?

Presentations are used in every marketing program. Your CEO may burnish your brand at an industry conference as part of your reputation programs. Webcasts may be a critical part of your demand generation, and your field sales force may need to learn the company pitch as part of sales enablement. Presentations are used all the time by analyst relations teams as part of market intelligence programs. But for as important as they are, why are there so many bad ones? Think about it—how often have you been utterly bored to tears watching someone drone on, or annoyed when a presenter tries to jam a hundred-slide presentation into thirty minutes?

But then again, there are speakers you remember. Presentations you remember. Maybe they were profound. Inspiring. Or maybe they just gave you exactly the information you were looking for—succinctly. This is not an accident. Good presentations do not occur by luck. Great presenters think long and hard about what they plan to say, prepare diligently, and practice, practice, practice.

The marketing team is responsible for creating presentations, presenting them, and training presenters from other departments. This post will cover the process of creating a good presentation. I am not going to cover presentation design, which is important, but less so than a good story and structure. I also don’t have space in this blog to cover the all-important process of speaker prep. If you want to know more about that, please refer to this longer post.

Conceiving the Presentation

Before creating a single slide, there is important work to be done. A presentation needs a purpose, a story and structure, and a clear sense of how it will open and end.

Purpose

Before effective presenters create any slides or write a script, they consider the purpose of the presentation. Are they looking to educate the audience concerning a new technology or technique? Are they attempting to demonstrate thought leadership by proposing bold new ideas? Is a salesperson trying to persuade a customer to select his or her product over the competition? Or, is the presentation an internal document intended to convince the CFO to increase the marketing budget?

An easy way to identify the purpose of a presentation is to ask yourself what you want your audience to be thinking as they leave the room. Your answer should frame your delivery and content. In this section, I will cover some of the more common elements you should consider when you define the purpose:

Educating

Selling

Convincing

Inspiring

Let’s take a closer look at each one.

When the purpose of your speech is to educate, make sure your pace is not too fast, use plenty of examples, and leave time for questions. Presenters who are trying to educate often hand out copies of their slides prior to the presentation. These handouts contain blanks next to the slides to encourage the listeners to participate by filling them in.

If your purpose is selling, then keep in mind that people do not like to be sold to, so your audience may put up a defensive mental barrier. To overcome this resistance, you should avoid over-the-top salesmanship, jargon, and smarmy behavior. Provide plenty of examples of how happy customers are using the product. Let these stories do the selling.

Convincing is a close cousin to selling. It applies to scenarios such as requesting a greater budget, investment in your startup, more headcount for your department, or the green light from the board for a new project. In such cases, make certain your business case or cause is rock solid, check and double-check all of your facts and numbers (errors are killers in these situations), and present a clear plan of how you will use the time, people, or money you are seeking.

Finally, presentations intended to inspire can be the most difficult to execute effectively. To a greater extent than the other types, they frequently rely on the presenter’s charisma more than anything else. If you are giving an inspiring presentation, make certain you have great stories that take your audience where you want them to go.

Story and Structure

Good presentations have a story. They have an arc. The purpose of a story arc—which is a standard motif in television dramas and movies—is to move a character or a situation from one state to another. The story arc need not be high drama. However, it must have a beginning, middle, and end. Ask any movie screenwriter, and he or she will tell you there’s a reason plays and movies have three acts—the format works. The key to creating the presentation, then, is to visualize that arc and how you are going to get the audience through your beginning, middle, and end in whatever time you have been allotted.

Brainstorming the Story

Two common methods to brainstorm stories are to use whiteboards and Post-it notes. Once you have a general idea of what you are going to talk about, sketch it out on the whiteboard. How you do this depends on your personality. Linear thinkers might use a timeline arc, highlighting the beginning, middle, and end, with all the points in between. Visual thinkers might prefer to draw a series of boxes to represent the slides, filling them in with key points and rough diagrams. Post-it notes can work the same way, but they are easier to reorder. Also, they enable you to discard ideas that don’t work.

Opening the Presentation

The worst opening to a presentation (next to silence and mortified stage fright) is something like this: “Hello, my name is John Smith, and I’m going to present to you on the history of axle grease.” Telling the audience the same thing that appears on your title slide does not add much value. In addition, you have likely been introduced already. Moreover, if you are at a conference, then your name will be in the program. Below is a much better method to begin a presentation:

Opening statement: Begin with a statement—perhaps your ultimate goal, a challenge to the audience, or a value proposition.

Summary: Briefly explain what you are going to cover—the bullets of your agenda.

Provocation: Make a controversial or challenging statement to get your audience’s attention.

Experience: Talk a bit about yourself, focusing on why your audience should listen to you.

Conclusion: Tell the audience where you will end up. This will automatically get your audience thinking about where you are leading them, predisposing them to listen carefully, even if they may disagree with your conclusion.

This structure is often shorthanded as “Tell them what you are going to tell them, tell them, and then tell them what you told them.” Reworking our bad axle grease example above, an effective opening might sound something like this:

Axle grease is one of the most important petroleum derivatives ever invented. It helps our cars run, our farms harvest, and our factories produce. Yet, we are at risk of underinvesting in the production of this vital resource, which could have a massive, if unknown, effect on our economy. To help you understand this issue, I’m going to give you a bit of a crash course on axle grease. I’ll highlight the main areas of the economy that rely on it and explain why we face a potential shortfall. I’ve been working in this industry for twenty years, most recently as the CEO of the largest producer, and this is the biggest crisis I have ever seen. At the end of our sixty minutes, I hope you understand why I say this and why it’s vital we fix this problem.

Admit it, even a mundane topic like grease comes alive when it is presented this way. The presenter has summarized his case, told you a bit about himself, and let you know how he’s going to be communicating with you over the course of the next hour.

The Meat of the Presentation

Make sure the presentation itself—the meat—matches the introduction and supports the key points you are trying to make. Resist the urge to load everything you could possibly think of into it (a common sin when presenters are creating new presentations by mixing and matching slides from existing presentations). A concise presentation that gives exactly what is promised is always better. And, you will avoid the presentation sin of rushing through your slides to try to finish within the allotted meeting or speaking slot time.

Closing the Presentation

A good closing ties back to the opening. Repeat the parts you want them to remember. Restate your provocation: “Now all of you understand why a shortage of axle grease would be catastrophic to our economy.” Some presenters use a journalistic technique known as the “kicker,” where they echo a theme from their opening in their closing. Our axle grease CEO might get cute with a kicker like: “I’m not just being a squeaky wheel. An axle grease shortage would be bad for all of us.” Use one of these two techniques and then thank the audience. You can display your contact information, but there’s no need to read it.

For more about how to design and present our axle great presentation, please refer to my longer post on the topic, or the full chapter on it in The Professional Marketer.

Thoughts? Or maybe you want to swap stories on the worst presentation you have ever seen? Let me know.

___

Startup Essentials is a series of excerpts from The Professional Marketer . I’ve pulled out what I think are the most essential skills a founder or a marketer at a startup would need.

July 27, 2015

Startup Marketing Essentials: #3 How to Develop a Positioning Statement

Positioning is sometimes referred to as the fifth P, along with product, price, place, and promotion. Founders spend the formative years of their companies answering a constant stream of questions from prospective employees, investors, and investors: What are you? Is that like so-and-so? How are you different from [insert large company that will no doubt crush you]? Developing a desired position, and formalizing it with a positioning statement, are critical steps on your way to profit and glory. – TM

A positioning statement is a short statement that demonstrates the value of what you offer, how it differs from your competition, and how it has a meaningful impact on your target audience. The positioning statement is an internal tool that you use to communicate your positioning. It codifies the customer benefit and the uniqueness of your product, service, brand, or company. It is the basis for all of your marketing messages and communications, including the development of a tag line. Other groups within your company can use the positioning statement to help them with their work. Your advertising team or agency, for example, can utilize the positioning statement as input to develop your advertisements. Understanding the target buyers, the value they see in your product, and how your product or service differs from competing products or services are essential components in creating a tag line that your target customers can identify with.

Developing a positioning statement requires a lot of hard work. The individuals involved need to question basic assumptions about their product or company, exchange opinions, resolve differences, and, most difficult of all, arrive at a final decision on a specific direction. Companies that lack the discipline needed to develop positioning and stick to a direction—and to the strategy that supports that direction—risk diffusing their marketing effort. The result is wasted time and, ultimately, wasted market opportunity.

The usual process for creating a positioning statement combines internal meetings and interviews with key stakeholders. Key stakeholders can include executives, founders, sales reps, and anyone you think really understands your customers and market. But even more important, and often missed, are interviews with customers, partners, and even prospects, if you can find them. Because the ultimate goal of positioning is to create a position in the mind of your customers or the market at large, understanding how your customers feel is essential to creating an effective statement.

Going further, you need to pay particular attention to your customers’ needs—what they are seeking in a product like yours—and how they perceive your product as different. A very difficult challenge in the positioning process occurs when customers feel differently about your product, service, or company than your executives do. Who is right? Do the customers just not get it? Or, is the company not delivering? Perhaps the company has never clearly articulated its position. As difficult as these discussions can be, this process can be a crucible from which something better can emerge.

After you have collected all of this feedback, the process of crafting the statement starts. Ideally, you should appoint a small group to complete the task. Otherwise, the process may never end. In the initial meeting, the group should collect as many ideas on the position of the company as possible. Its next task is to take a stab at crafting the actual statement.

The positioning statement should be an honest reflection of your product, service, or brand. The key to a good statement is specificity: capture what your company delivers and how it differs from the competition. In addition to being informational, the statement can also be aspirational. For example, if your company has a three-year plan to add features to a product, grow your footprint, capture market share, or achieve some other objective, the positioning statement can reflect these goals.

There are two widely used templates for positioning statements:

For (target audience), (product/service/ brand) is the (frame of reference) that delivers (benefit/differentiator) because only (product/service/brand name) is (reason to believe).

For (target audience) who wants/needs (reason to buy your product/service/brand), the (product/service/brand) is a (frame of reference) that provides (your key benefit). Unlike (your main competitor), the (product/service/brand) provides (your key differentiator).

The positioning statement must convey the purpose and impact of your business quickly yet convincingly. For this reason, both templates are short and concise. The second template more directly addresses your key differentiator and the contrasts with your competition.

Both templates include the basic components below. The second template is more explicitly aimed against a competitor and breaks out its name and the differentiator.

Target audience – The demographic or psychographic description of your desired customer. This is who your product, service, or brand is intended for, and it includes customers who most closely represent your product, service, or brand’s most fervent users.

Product/service/brand – What you’re marketing. This might seem like a simple step, but take a few moments to reflect on exactly what you are attempting to position. Is it the product or service itself? Or, is it your company?

Frame of reference – The category or market in which your product, service, or brand competes. Establishing a frame of reference helps provide context for your brand and relevance to your customers.

Benefit/differentiator – The most compelling and motivating benefit your brand offers your target audience relative to your competition.

Product/service/brand name – The name of the product, service, or brand you are positioning.

Reason to believe – Proof that your product, service, or brand delivers what it promises.

Here is how I position my book, The Professional Marketer:

For professional marketers who need to learn fundamental marketing skills, this book is a professional development tool that provides easy-to-understand and pragmatic advice to help them get their job done. Unlike searching through blogs or reading dozens of marketing texts, The Professional Marketer boils it down to provide a convenient and authoritative overview that can be applied directly to the job at hand.

After you have crafted your statement, it is essential that you test it. If the statement is going to inform your go-to-market plan and guide your marketing efforts, then it has to hold up. To ensure that the statement works, you need to ask a number of critical questions:

Is the statement clear?

Does it focus on and motivate the core target audience?

Does it provide a distinctive and meaningful picture of your product, service, or brand?

Does it differentiate your brand from the competition?

Is it credible?

Does it allow for future growth?

Make sense? Can you succinctly describe your startup in a way that answers these questions?

Startup Marketing Essentials is a series of excerpts from The Professional Marketer . I’ve pulled out what I think are the most essential skills a founder or a marketer at a startup would need.

Photo courtesy of MioszB

July 13, 2015

Startup Marketing Essentials: #2 Market Sizing and Segmentation

If TAM, SAM and CAGR mean nothing to you, you have a problem. Whether you are creating or disrupting a market, knowing how big it is, and what segments are most ripe for the picking are critical. – TM

There is a common sin that marketers frequently commit. In their rush to build a website or create an attractive logo, they forget something very important: who is the buyer? These marketers are firing without aiming. They are being tactical and not strategic. Sometimes they are simply shooting to make it seem as if they are doing something.

To build an effective marketing strategy, you need to understand who will be buying your product. This means, among other things, that you need to calculate how big the potential market is for your product or service and how much of that market will be contested by your competitors. And, if you are really good, you will learn not just who those buyers are but why they purchase the goods and services they do.

Market Segmentation

A market is a place where trade takes place. Markets are dependent on two major participants—buyers and sellers. Market segmentation is what the name suggests—understanding the overall potential market for your product and determining which subsets, or segments, of that market are most likely to buy from you.

Market segmentation varies somewhat depending on whether you are selling B2C or B2B. Regardless, most of the core concepts are the same. You will just be segmenting using different criteria.

For B2B markets, there are three fundamental characteristics of the customer that your company should know: location, company size, and industry. Let’s take a closer look at each one.

Location – Where is the company located? Most commonly, marketers perform this segmentation at the country level. For smaller businesses with less reach, or for certain types of products or services, however, segmentation can be performed on the level of a state, a province, or even a city. In some cases, segmentation considers whether the target company is located in a major metropolitan area, a suburb, an exurb, or a rural area, although this level of segmentation is more common for B2C markets.

Company size – Is the company a small business, a midsized business, or a large enterprise? This information is valuable, because it helps the seller determine whether its products meet the target company’s needs and the target company can afford them. Although definitions of these three segments vary, the most common breakdown is:

small businesses have fewer than 100 employees;

midsized businesses have 101 to 1000 employees;

enterprises have more than 1000 employees.

Some marketers divide one or more of these categories into subsegments. For example, the small office / home office (SOHO) segment is a small business with fewer than ten employees. Other marketers add segments; for example, large enterprises for companies with more than five thousand employees. (FYI: all of the Forbes Global 2000 fall within this subsegment.) Which system you adopt depends on the nature of your organization, its products and/or services, and its goals and strategies. The most basic rule is to use segments that make sense for your business.

Industry – Different industries have different needs, and knowing which industries need your products and services is a critical aspect of segmentation. You can obtain lists of industries—and subindustries—from a number of sources. The most common source is the Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) code. The US government created the SIC codes in 1937 to establish a standard system that all federal agencies and departments would use to classify industries. All SIC codes consist of four digits. For example, the industry SIC code for Metal Mining is 1000. Within this industry are numerous subindustries, such as Gold and Silver Ores (1040) and Miscellaneous Metal Ores (1090).

Market Sizing

Clearly, identifying the viable markets and market segments for your products and/or services is essential to your company’s success. Regardless of the markets in which you operate, however, it is essential that you have an accurate knowledge of their size.

It’s probably safe to assume that everyone wants to do business in a large and fast-growing market. However, it is possible to make money in a niche or a nascent market. You can also be successful if you introduce a revolutionary product that is just the tonic for customers who are fleeing a declining market. The point is, you can make money in all types of markets.

How can you determine how large your target market is? There are several standard metrics you can use to measure markets.

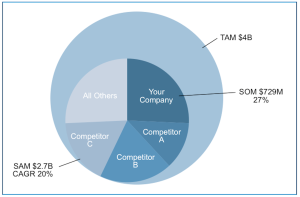

Total available market (TAM) – This is the total size of the market. It is also referred to as total addressable market.

Served available market (SAM) – Also known as served addressable market, the SAM is the total size of the market that is currently being served, or sold to. It is a portion of the TAM, and therefore it is always smaller. For example, according to the research firm IDC, 659.8 million smartphones were shipped in 2012, up 33.5 percent from the 494.2 million units shipped in 2011. (International Data Corporation. “Worldwide Smartphone 2012–2016 Forecast and Analysis,” March 2012) Assuming all of these are sold, then the SAM is 659.8 million, plus the smartphones previously sold, minus the number taken out of service. A big number, but nothing compared with a potential TAM in the billions if every adult in the world owned one.

Share of market (SOM) – More commonly referred to as market share, this is the percentage of the market that a given company owns.

Market growth – This is the rate by which the TAM is growing. It is typically calculated on an annual basis and expressed as compound annual growth rate (CAGR, pronounced “ka-grr”).

Figure 1 Market sizing graph – composite TAM, SAM, SOM, and CAGR

You can obtain many of these numbers from analysts who follow your industry or product. If you are selling something new, you may need to extrapolate or combine research to create an approximation, or “comp,” of your market.

A bit of advice to those of you who create marketing plans: Never walk into the boardroom with only the TAM. From personal experience, I can tell you this is one of the fastest ways to get thrown out of said boardroom. You need to understand the market dynamics—what your competitors are doing, price pressures, the strength of your brand—better than that. Also, never say the following: “This market is so big; if we captured only one percent of it, we’d all be rich.” I know more than one venture capitalist who stops listening to your pitch at that point. No one goes into business to get a 1 percent share, and presenting this argument suggests that you don’t have a very sound strategy.

An accurate knowledge of market size is critical to understanding the dynamics of a market—current or new—and assessing whether there is room for growth. Good markets are typically large and have a gap between the TAM and the SAM. This gap represents sales opportunity for your business. Opportunity also arises when the vendor with the largest SOM is vulnerable and your company feels it can take away market share based on an advantage in your product, price, or distribution. Another strategy for stealing market share is aggressive promotion. One of the best examples of this strategy is the market share gained by online insurance companies such as GEICO and Progressive. With essentially the same product, offered for a bit less via direct sales as opposed to agents, aggressive promotion via television advertising enabled these companies to dramatically increase their market share. As of 2011, GEICO is the third largest auto insurance provider in the United States, and grew at 7 percent, while the CAGR for the overall auto insurance market is only 1 percent. GEICO is stealing market share.

The best way to size markets is to perform both a top-down and a bottom-up analysis. Find analyst reports that provide the TAM, growth rate, and market share, if they are available. Then, balance that top-down approach with your own bottom-up calculations based on your price, manufacturing capacity, and sales reach.

Startup essentials is a series of excerpts from The Professional Marketer. I’ve pulled out what I think are the most essential skills a founder or a marketer at a startup would need.

July 6, 2015

Startup Marketing Essentials: #1 The Four Ps

I was introduced to E. Jerome McCarthy’s four P’s later in my career. I wish I had known them earlier. There is no more perfect summation of marketing. Each of the P’s is a lever at your disposal. As a startup founder or CEO, understanding the four P’s will help you know which of the four levers to pull to beat your competition. — TM

What is marketing? Ask one hundred marketers, and you are likely to get one hundred different answers. Consult the dictionary, and you find stolid definitions like the following: “The commercial functions involved in transferring goods from producer to consumer.” But, what does that really mean? And what exactly would a head of marketing be in charge of?

In his 1960 book Basic Marketing. A Managerial Approach, E. Jerome McCarthy, a marketing professor at Michigan State University, created a simplified model and mnemonic for the key elements of marketing. His model is known as the Four Ps: product, price, place, and promotion. McCarthy’s model was a simplification of earlier work on the key marketing ingredients, or “marketing mix,” by Neil Borden from Harvard Business School.

Let’s take a closer look at McCarthy’s Four Ps.

Product – Refers to the actual goods or services, and how they relate to the end-user’s needs and wants. The scope of a product also includes supporting elements such as warranties, guarantees, and customer service.

Price – Refers to the process of setting a price for a product, including discounts. Although most often price is described in terms of currency, it doesn’t have to be. What is exchanged for the product or services can be time, energy, or even attention.

Place – Indicates how the product gets to the customer; for example, point-of-sale placement and retailing. Also known as Distribution, place can refer to the channel by which a product or service is sold (e.g., online vs. retail), the geographic region, (e.g., Western Europe) or industry (e.g., Financial Services), and the target market segment (e.g., young adults, families, business people).

Promotion – Refers to the various strategies for promoting the product, brand, or company, including advertising, sales promotion, publicity, personal selling, and branding.

In practice, the Four Ps should be thought of as four levers. To grow a business or to fix a faltering business, you need to employ one or more of the Four Ps. Moving those levers up or down as needed will have a direct impact on the business.

McCarthy’s Four Ps are perhaps the most important concept a marketer can master. You will be hard pressed to find a more concise and durable definition of marketing. The Four Ps will serve you well when you need to determine whether you are working on the right things.

Startup essentials is a series of excerpts from The Professional Marketer. I’ve pulled out what I think are the most essential skills a founder or a marketer at a startup would need.