Lori Robinson's Blog, page 4

April 16, 2022

Earth Day, Every Day

What is Earth Day? It’s a day to celebrate, praise and notice Mother Earth. A day to remember all she is, all she does, and all she gives. A reminder that without Mother Earth, none of us would be alive.

For Earth Day, and every day for that matter, go outside. Take some deep breaths. Soak up the sunlight. Taste the air on your tongue, feel the wind kiss your cheeks, let your bare feet meet the dirt, grass, and sand.

Go for a walk. Look, listen and smell the world around you. Engage all of your senses and notice what you often don’t. Notice the breathtaking display of flowers and bushes, grasses and trees – everywhere. Breathe in their scents. Notice the chirps, buzz and clicks of birds, insects, and squirrels. What are they saying? Notice the colors – every shade of every color, everywhere.

Say outloud, hello natural world, I see you.

And then try to comprehend the miraculous biodiversity of life. Try to imagine all that Mother Nature is, all that Mother Nature has and all that Mother Nature does for us. Really try to understand—reach and bend and stretch until your heart and mind are gaping.

Then celebrate her.

Kiss the trees. Dance in a meadow. Sing with the birds. Play in the dirt. Join the animals and the birds and the angels, the silent song of the flowers and trees in praise of her.

And honor her with a commitment to action.

Pick up litter, plant a garden, feed the birds, remove a fence, let a weed grow, let a raccoon share your patio, save a spider.

Let her know you are grateful…. So grateful.

Wish Mother Earth a happy Earth Day and make a promise that when people ask when is Earth Day, you will answer, “Every day!”

The post Earth Day, Every Day appeared first on Saving Wild.

March 20, 2022

Being Jane Goodall

Jane Goodall’s birthday is April 3rd. She will be 88. By that time in life, most people have chosen to retire, slow down and live a more quiet life. But being Jane Goodall, she has done the opposite.

She has turned up the volume on her work to save the world’s wild ones and wild places. Most years she travels over 300 days giving lectures, attending meetings like CITIES, accepting honors, and visiting and inspiring hoards of school children who are members of her worldwide Roots & Shoots program. Not even the pandemic slowed down her busy schedule, albeit she did most of her meetings on line.

If there is news about wildlife, Dr. Jane is among the first to give a comment or make a widely quoted statement. Most recently she has been speaking out about the wildlife trade (as it relates to the spread of viruses), and with editor Doug Abrams Jane wrote The Book of Hope.

In every way, she is a model for hope, and a purposeful well lived life.

In celebration of my friend Dr. Jane’s birthday I’ve highlighted 14 characteristics I consider essential to being Jane Goodall.

I believe each of us can emulate some (or all) of these attributes to help us live our uniquely best purposeful life.

Dr. Jane has been my role model since I was about six years old.

Dr. Jane has been my role model since I was about six years old.Find your passion and do not waiver from it. Since she was born (I am exaggerating but you get the gist) Jane Goodall knew she wanted to help animals. Imagine if you’ve spent 20, 40, 80 years focused on one thing. You would be an expert at it. And you would achieve a lot. Most of us get taken off our path because of impatience or because of family or cultural pressures. Find your passion and stick with it.

Be Yourself. There is no doubt in anyone’s mind what Jane Goodall stands for. She follows her own calling and passion. That makes her both unique and highly effective. So be yourself. Everyone else is taken.Be disciplined. Jane has a mission-like attitude. Indeed she is on a mission, and you feel it from all of her actions. She gets the job done no matter how tired, or overworked she is. And she doesn’t complain.Surround yourself with influential friends. And do things for them. Jane sometimes lends her name for events her friends are doing. She did a foreword for one of my books. She is generous with her time and heart. And people want to be around her and give back to her as well. Motivational teachers all tell us the same thing, “you are only as successful as the people you surround yourself with.” So surround yourself with people you want to emulate.Be determined. Did you know that Jane describes herself as a frail child, prone to sickness. A Doctor once told her she would never be able to follow her dream to go to Africa because she did not have the physical aptitude for it. She had to overcome her shyness in order to be a speaker? She had to overcome many obstacles to be able to do field work in Gombe Stream, including being told she would not be allowed in the Park without a chaperone (that’s when her mother Vanne came to her rescue). Determination will get you far along your path in life.Adopt a minimalist mindset. Although I doubt Jane cares about the label of minimalist, she has always lived simply, even before a minimalist lifestyle was popular. Her staff told me she lives out of one small piece of luggage. And I took this photo of the bed she slept in for years in her home in Tanzania. A simple, no fuss lifestyle leaves alot of time and energy for other things besides maintaining a high end complicated lifestyle. Dr. Jane’s bed at her house in Tanzania.MORE ON BEING JANE GOODALLWalk your talk. Knowing who you are, and what you are most passionate about, makes you believable to others. Because meat consumption is a huge contributor to climate change, and because of the abuse and suffering animals endure in factory farms, Jane is a vegan except when her grueling travel schedule only has vegetarian options. Take a stand for what you believe in and make sure you make all your lifestyle choices reflect your values and beliefs.Don’t give up. In the preface of my book,

Saving Wild, Inspiration From Fifty Leading Conservationists

, I tell a story about the time I asked Jane, “How do you keep going despite all the overwhelming bad news in the world?” She fixed her green gold-speckled eyes on mine and said, “I never give up.” At 88 Jane is probably doing more than ever to share her cause. The words, never give up, are simple. But they can be very difficult to put into action.Keep a sense of humor. Even though Dr. Jane works in a field that is challenging, and at times overwhelming and depressing, she seems to remain in good spirits.

Dr. Jane’s bed at her house in Tanzania.MORE ON BEING JANE GOODALLWalk your talk. Knowing who you are, and what you are most passionate about, makes you believable to others. Because meat consumption is a huge contributor to climate change, and because of the abuse and suffering animals endure in factory farms, Jane is a vegan except when her grueling travel schedule only has vegetarian options. Take a stand for what you believe in and make sure you make all your lifestyle choices reflect your values and beliefs.Don’t give up. In the preface of my book,

Saving Wild, Inspiration From Fifty Leading Conservationists

, I tell a story about the time I asked Jane, “How do you keep going despite all the overwhelming bad news in the world?” She fixed her green gold-speckled eyes on mine and said, “I never give up.” At 88 Jane is probably doing more than ever to share her cause. The words, never give up, are simple. But they can be very difficult to put into action.Keep a sense of humor. Even though Dr. Jane works in a field that is challenging, and at times overwhelming and depressing, she seems to remain in good spirits.

Remain Hopeful. Despite the fact that conservation is one of the most difficult fields to work in, she refuses to give up hope. Having an indomitable spirit is a quality she acknowledges as important. In fact, one of the many things Jane is known for is her focus on Hope. She has numerous books on Reasons for Hope including her most recent, The Book of Hope. “Hope is infectious,” she says. “Without hope, there is no hope.”Give people your full attention. If you have ever met and had a conversation with Jane you know she looks you straight in the eyes making you feel there is no one else in the room. Present, focused, and curious. All great qualities for greatness.Say Yes. Jane graciously gives her name to causes that are in line with the mission of her Jane Goodall Institute. That selflessness has only served to expand her name and message across the world.Learn to speak well. Jane is one of the best public speakers I have ever heard. Every one of her lectures has a signature beginning that initially grabs the audience’s attention. Watch her signature opening on my YouTube channel here. She follows her crowd pleasing opening with stories that evoke emotion. I have been in the audience many times when she was speaking and I always notice people crying and laughing, both signs that the audience is taking the message to heart. Be humble. Dr. Jane Goodall is perhaps the best-known name in the world related to conservation and animals, yet she remains unpretentious, simple and gracious.

We need inspiration now more than ever. And Dr. Jane continues to provide it through her work, and who she is in the world. By simply being Jane Goodall.

Happy Birthday Jane Goodall.

For more on Jane Goodall check out my post, What you don’t know about Dr. Jane.

The post Being Jane Goodall appeared first on Saving Wild.

On Being Jane Goodall

Jane Goodall’s birthday is April 3rd. She will be 88. By that time in life, most people have chosen to retire, slow down and live a more quiet life. But being Jane Goodall, she has done the opposite.

She has turned up the volume on her work to save the world’s wild ones and wild places. Most years she travels over 300 days giving lectures, attending meetings like CITIES, accepting honors, and visiting and inspiring hoards of school children who are members of her worldwide Roots & Shoots program. Not even the pandemic slowed down her busy schedule, albeit she did most of her meetings on line.

If there is news about wildlife, Dr. Jane is among the first to give a comment or make a widely quoted statement. Most recently she has been speaking out about the wildlife trade (as it relates to the spread of viruses), and with editor Doug Abrams Jane wrote The Book of Hope.

In every way, she is a model for hope, and a purposeful well lived life.

In celebration of my friend Dr. Jane’s birthday I’ve highlighted 14 characteristics I consider essential to being Jane Goodall.

I believe each of us can emulate some (or all) of these attributes to help us live our uniquely best purposeful life.

Dr. Jane has been my role model since I was about six years old.

Dr. Jane has been my role model since I was about six years old.Find your passion and do not waiver from it. Since she was born (I am exaggerating but you get the gist) Jane Goodall knew she wanted to help animals. Imagine if you’ve spent 20, 40, 80 years focused on one thing. You would be an expert at it. And you would achieve a lot. Most of us get taken off our path because of impatience or because of family or cultural pressures. Find your passion and stick with it.

Be Yourself. There is no doubt in anyone’s mind what Jane Goodall stands for. She follows her own calling and passion. That makes her both unique and highly effective. So be yourself. Everyone else is taken.Be disciplined. Jane has a mission-like attitude. Indeed she is on a mission, and you feel it from all of her actions. She gets the job done no matter how tired, or overworked she is. And she doesn’t complain.Surround yourself with influential friends. And do things for them. Jane sometimes lends her name for events her friends are doing. She did a foreword for one of my books. She is generous with her time and heart. And people want to be around her and give back to her as well. Motivational teachers all tell us the same thing, “you are only as successful as the people you surround yourself with.” So surround yourself with people you want to emulate.Be determined. Did you know that Jane describes herself as a frail child, prone to sickness. A Doctor once told her she would never be able to follow her dream to go to Africa because she did not have the physical aptitude for it. She had to overcome her shyness in order to be a speaker? She had to overcome many obstacles to be able to do field work in Gombe Stream, including being told she would not be allowed in the Park without a chaperone (that’s when her mother Vanne came to her rescue). Determination will get you far along your path in life.Adopt a minimalist mindset. Although I doubt Jane cares about the label of minimalist, she has always lived simply, even before a minimalist lifestyle was popular. Her staff told me she lives out of one small piece of luggage. And I took this photo of the bed she slept in for years in her home in Tanzania. A simple, no fuss lifestyle leaves alot of time and energy for other things besides maintaining a high end complicated lifestyle. Dr. Jane’s bed at her house in Tanzania.MORE ON BEING JANE GOODALLWalk your talk. Knowing who you are, and what you are most passionate about, makes you believable to others. Because meat consumption is a huge contributor to climate change, and because of the abuse and suffering animals endure in factory farms, Jane is a vegan except when her grueling travel schedule only has vegetarian options. Take a stand for what you believe in and make sure you make all your lifestyle choices reflect your values and beliefs.Don’t give up. In the preface of my book,

Saving Wild, Inspiration From Fifty Leading Conservationists

, I tell a story about the time I asked Jane, “How do you keep going despite all the overwhelming bad news in the world?” She fixed her green gold-speckled eyes on mine and said, “I never give up.” At 88 Jane is probably doing more than ever to share her cause. The words, never give up, are simple. But they can be very difficult to put into action.Keep a sense of humor. Even though Dr. Jane works in a field that is challenging, and at times overwhelming and depressing, she seems to remain in good spirits.

Dr. Jane’s bed at her house in Tanzania.MORE ON BEING JANE GOODALLWalk your talk. Knowing who you are, and what you are most passionate about, makes you believable to others. Because meat consumption is a huge contributor to climate change, and because of the abuse and suffering animals endure in factory farms, Jane is a vegan except when her grueling travel schedule only has vegetarian options. Take a stand for what you believe in and make sure you make all your lifestyle choices reflect your values and beliefs.Don’t give up. In the preface of my book,

Saving Wild, Inspiration From Fifty Leading Conservationists

, I tell a story about the time I asked Jane, “How do you keep going despite all the overwhelming bad news in the world?” She fixed her green gold-speckled eyes on mine and said, “I never give up.” At 88 Jane is probably doing more than ever to share her cause. The words, never give up, are simple. But they can be very difficult to put into action.Keep a sense of humor. Even though Dr. Jane works in a field that is challenging, and at times overwhelming and depressing, she seems to remain in good spirits.

Remain Hopeful. Despite the fact that conservation is one of the most difficult fields to work in, she refuses to give up hope. Having an indomitable spirit is a quality she acknowledges as important. In fact, one of the many things Jane is known for is her focus on Hope. She has numerous books on Reasons for Hope including her most recent, The Book of Hope. “Hope is infectious,” she says. “Without hope, there is no hope.”Give people your full attention. If you have ever met and had a conversation with Jane you know she looks you straight in the eyes making you feel there is no one else in the room. Present, focused, and curious. All great qualities for greatness.Say Yes. Jane graciously gives her name to causes that are in line with the mission of her Jane Goodall Institute. That selflessness has only served to expand her name and message across the world.Learn to speak well. Jane is one of the best public speakers I have ever heard. Every one of her lectures has a signature beginning that initially grabs the audience’s attention. Watch her signature opening on my YouTube channel here. She follows her crowd pleasing opening with stories that evoke emotion. I have been in the audience many times when she was speaking and I always notice people crying and laughing, both signs that the audience is taking the message to heart. Be humble. Dr. Jane Goodall is perhaps the best-known name in the world related to conservation and animals, yet she remains unpretentious, simple and gracious.

We need inspiration now more than ever. And Dr. Jane continues to provide it through her work, and who she is in the world. By simply being Jane Goodall.

Happy Birthday Jane Goodall.

For more on Jane Goodall check out my post, What you don’t know about Dr. Jane.

The post On Being Jane Goodall appeared first on Saving Wild.

January 30, 2022

Becoming The White Masai

While reading The White Masai several years ago, I was shocked by the author’s decision to leave her home in Germany to marry a Masai man and acclimate to his culture and way of life. Honestly, I questioned her sanity.

The Masai’s way of life represents simplicity.Ultimate minimalists, the Masai are part of the land and animals and connected to the earth in ways we in the modern world no longer are. They build with dung and mud, sleep on goat-skins, and drink blood and milk. They spend their time outside under the sky, entering their homes only to cook and sleep. They walk miles to visit friends in nearby villages and collect water carried on the backs of donkeys.

They generally have no TV’s, no books, no chairs, no toilets, no lights. The children play games with sticks and rocks in the dirt, the men light fires from dust, and the women bead beautiful jewelry for their husbands.

Trading shoes with Daniel, my Masai guide.

Daniel doesn’t like my flip-flops, “the thorns will push right through the bottoms,” he says. His sandals, made from old rubber tires are the only shoes he’s worn for the past seven years. “They will last another seven,” he tells me.

Daniel and me co-guiding my group on safari in the Masai Mara.MASAI ARE GREAT GUIDES

Daniel and me co-guiding my group on safari in the Masai Mara.MASAI ARE GREAT GUIDESDaniel works as a safari guide in the Masai Mara, Kenya’s most popular wildlife park. He grew up on this land. As part of his initiation into warrior status he lived with his peers for three years in the bush sleeping under stars and eating plants and occasionally meat. He learned life long survival skills including protecting himself from lion, elephant, and buffalo.

Listen to Daniel Sing the Lion Warrior SongHe is the best wildlife spotter I’ve hired during the 18 years I’ve been leading safaris to Africa. From miles away, with his naked eyes, he sees lions that I can barely spot through my binoculars. He knows what an animal is about to do. He maneuvers his truck away from the pack of safari vehicles suffocating each other around a wildlife sighting, correctly anticipating when the animal will move away to drink water, climb a tree, or try to hunt.

Of all the indigenous tribes in the world, the Maasai have a reputation for holding onto their culture despite the governments’ desire to change them.

Daniel sees photos of America, and tells me he has no interest in going there. “Four-lane roads and tall buildings,” is how he describes my country.

I’m drawn to Daniel. It’s a soul attraction. A connection to the minimalist side of me that is forever intimately tied to the natural world. I no longer question the decision of the author of the White Masai to exchange her world for theirs.

The post Becoming The White Masai appeared first on Saving Wild.

On Becoming The White Masai

While reading The White Masai several years ago, I was shocked by the author’s decision to leave her home in Germany to marry a Maasai man and acclimate to his culture and way of life. Honestly, I questioned her sanity.

The Masai’s way of life represents simplicity.Ultimate minimalists, the Maasai are part of the land and animals and connected to the earth in ways we in the modern world no longer are. They build with dung and mud, sleep on goat-skins, and drink blood and milk. They spend their time outside under the sky, entering their homes only to cook and sleep. They walk miles to visit friends in nearby villages and collect water carried on the backs of donkeys.

They generally have no TV’s, no books, no chairs, no toilets, no lights. The children play games with sticks and rocks in the dirt, the men light fires from dust, and the women bead beautiful jewelry for their husbands.

Trading shoes with Daniel, my Maasai guide.

Daniel doesn’t like my flip-flops, “the thorns will push right through the bottoms,” he says. His sandals, made from old rubber tires are the only shoes he’s worn for the past seven years. “They will last another seven,” he tells me.

Daniel and me co-guiding my group on safari in the Masai Mara.MAASAI ARE GREAT GUIDES

Daniel and me co-guiding my group on safari in the Masai Mara.MAASAI ARE GREAT GUIDESDaniel works as a safari guide in the Masai Mara, Kenya’s most popular wildlife park. He grew up on this land. As part of his initiation into warrior status he lived with his peers for three years in the bush sleeping under stars and eating plants and occasionally meat. He learned life long survival skills including protecting himself from lion, elephant, and buffalo.

Listen to Daniel Sing the Lion Warrior SongHe is the best wildlife spotter I’ve hired during the 18 years I’ve been leading safaris to Africa. From miles away, with his naked eyes, he sees lions that I can barely spot through my binoculars. He knows what an animal is about to do. He maneuvers his truck away from the pack of safari vehicles suffocating each other around a wildlife sighting, correctly anticipating when the animal will move away to drink water, climb a tree, or try to hunt.

Of all the indigenous tribes in the world, the Maasai have a reputation for holding onto their culture despite the governments’ desire to change them.

Daniel sees photos of America, and tells me he has no interest in going there. “Four-lane roads and tall buildings,” is how he describes my country.

I’m drawn to Daniel. It’s a soul attraction. A connection to the minimalist side of me that is forever intimately tied to the natural world. I no longer question the decision of the author of the White Masai to exchange her world for theirs.

The post On Becoming The White Masai appeared first on Saving Wild.

January 18, 2022

Five NGO’s Helping Animals that deserve your 2022 donation

You have enough to do then spend your time researching which organizations deserve your donations. So let me help you.

Here are my favorite five non-governmental organizations helping animals.

I have personally vetted each of these, giving them a ‘thumbs up’ for their effectiveness, ethics, and ability to use your money wisely. They are all unique and probably ones you have not heard of.

If you want to help animals, you can’t go wrong donating to any, or all, of these wonderful organizations.

On the other hand, maybe you want to avoid sending out five separate donations, and being solicited from them in the future?

Then simply donate to SavingWild here:

[Note: Donations are processed through our non-profit umbrella, The Key Biscayne Foundation, and are fully tax-deductible.]

[Note: Donations are processed through our non-profit umbrella, The Key Biscayne Foundation, and are fully tax-deductible.] Your money will be bundled with other donors and distributed among these five organizations helping animals. And we never send out solicitations!

Here are my Favorite five NGO’s Helping Animals

I recently had the privilege of visiting this new sanctuary in Northern Kenya’s Samburu region. So many of the orphaned elephants in Kenya come from this area so it makes my heart sing to know that these traumatized babies can now be taken care of on the land they are familiar with, near elephant families they recognize, rather than flown or trucked hours away to be cared for in Nairobi.

Created by the Wildlife Conservation Network in partnership with the Leonardo DiCaprio Foundation, the Lion Recovery Fund invests in projects in both Africa and in western donor countries committed to recovering lions and restoring their wild landscapes. The Fund’s goal is to operate until lions are on a clear path toward doubling their numbers across Africa.

Animal Defenders International

It seems like I receive news from ADI on a weekly basis about their efforts to rescue lions and tigers from life as a circus act. This organization is busy all over the world identifying abuse and providing rescue. I admire their work, but beware that once you are on their list, you will receive an overwhelming number of solicitations.

Photos by safari client Henry Holdsworth @Wild by Nature Gallery

Photos by safari client Henry Holdsworth @Wild by Nature Gallery

Great Plains Foundation supports the work of Great Plains Conservation which acquires and then converts hunting concessions into conservation areas in Africa. The Foundation arm creates and funds projects that will rehabilitate, enhance and save the wildlife in these protected areas. I support anything Dereck and Beverly Joubert are connected to, including using some of their wonderful Tented Camps in my safari itineraries. Visit my YouTube channel to get a feel for some of the camps I like.

A model for the future of conservation around the globe, NRT empowers local people to build sustainable economies linked to conservation and the protection of wild spaces, and mend years of tribal conflict. NRT was founded by Ian Craig, one of the conservationist heroes in my book, Wild Lives. I often include this area of in Northern Kenya on my safari itineraries. It is full of the Big Five and my clients can learn about the amazing work they are doing.

Make it Simple. Donate to SavingWild and we will bundle your donation with others and distribute it for you.DONATE DIRECTLY TO SAVINGWILD USING THIS LINK:

[Donations are processed through our non-profit umbrella, The Key Biscayne Foundation, and are fully tax-deductible.]

The post Five NGO’s Helping Animals that deserve your 2022 donation appeared first on Saving Wild.

January 10, 2022

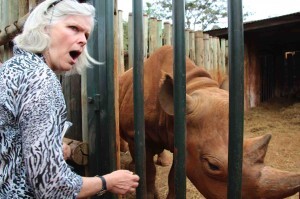

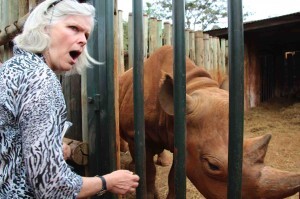

Meeting Max the Rhinocerous

Rhinocerous have always appeared to me to be elusive, other-worldly beings. Most people, including me, who have been lucky enough to see a rhinoceros in the wild don’t usually speak about them with the same emotional furor used when talking about elephants, big cats or gorillas.

The rhino’s pre-historic coats of armor don’t inspire warm and cuddly feelings.

And, although I was always elated to see one on safari, the emotions were ephemeral, a result of understanding how rare the sighting was.

Rhinos and leopards are the rarest of the Big 5 to spot on safari

Rhinos and leopards are the rarest of the Big 5 to spot on safariAll of that changed when I met Max.

After reading Daphne Sheldrick’s book, Love, Life and Elephants, I visited her elephant orphanage in Kenya. Although the main attraction is the orphaned baby elephants, at the end of my visit there I noticed a large fenced in area separated from the elephants stalls.

Inside was an intimidating bulk of animal – a one-and-a-half-ton rhinoceros. “That’s Max,” one of the caregivers told me. “He’s blind.”

I approached the enclosure and stood next to the green metal gate. As soon as I began sending out a heart felt connection toward Max he turned and walked straight towards me from the opposite side of the enclosure.

PETTING A RHINOCEROUSTwo lethal looking horns projected from the front of his head as he maneuvered his body sideways against the steel bars that separated us.

I reached my hand through the slat. Doubting he could sense my touch through rhino skin that felt dry and gritty like sandpaper, I began to scratch. I rubbed around his face, ears, and cheeks.

His head sunk incrementally lower and lower toward the ground as his neck muscles gave way to my rhino massage.

And then he closed his eyes and moved towards my hand so that I was touching his belly. He wanted a belly rub.

blind Max asking to be rubbed. photo: Barbara Calvo

blind Max asking to be rubbed. photo: Barbara CalvoThen I heard a long low sigh coming from deep inside of Max’s physical and emotional being.

Is he crying? I wondered.

What is Max saying? Photo: Barbara Calvo

What is Max saying? Photo: Barbara CalvoFound blind and motherless, I learned that Maxwell was brought to the elephant orphanage at the start of 2007.

As I continued to stroke his belly I began crying.

Weeping for my lack of understanding of this magnificent animal, and for all the pain inflicted on his species.

RHINO POACHING CRISIS

About 1,000 rhinos are killed by poachers annually, and there are an estimated 25,000 left in the wild.

The poachings have a mafia-like level of sophistication, and the prices fetched ($133 per gram of powdered horn) equal profits rivaled in drug and sex trafficking.

The rhino’s horns are brutally hacked off their faces (fatally wounding the animals) and then shipped to Laos, China, and Vietnam where the horns are used as high-level gifts by governmental officials and other wealthy business people.

Credit: World Rhino Day web site

Credit: World Rhino Day web siteThe crazy thing is, the horns are made of keratin, the same substance of our finger and toenails.

Good News for RhinoOn most of my Kenya safari itineraries I include the Lewa Wildlife Conservancy. The place started as a rhino sanctuary and has become a model of conservation worldwide. Working with the local communities in the area Lewa has had zero rhino poaching incidents for many years so tourists are basically guaranteed to see wild rhinoceros.

When I told Max’s caretakers at the Sheldrick orphanage that Max seemed to be crying while I caressed him, they replied, “No, no, he wasn’t crying. He was happy,” they said. “He loves to be touched and he especially loves to be tickled.”

Rhinos love to be tickled. The words flipped my heart and head around. But then I found myself asking, who doesn’t like to be tickled?

Since meeting Max the rhinoceros whenever I now see a rhino on my safaris I feel an emotional connection to the sweet, sensitive, misunderstood rhinoceros being.

****

WHAT YOU CAN DO TO HELP SAVE RHINO FROM EXTINCTION:

Donate to Saving Wild and we will send your money to the best organizations helping to save the rhino from extinction. To make a donation, go here.

The post appeared first on Saving Wild.

How A Rhinocerous Named Max Altered My Perceptions

Rhinos have always appeared to me to be elusive, other-worldly beings. Most people, including myself, who have seen the rare rhinoceros don’t usually talk about them with the same emotional furor used to speak about elephants, big cats or gorillas.

The rhino’s pre-historic coats of armor don’t inspire warm and cuddly feelings.

And, although I was always elated to see one on safari, the emotions were ephemeral, a result of understanding how rare the sighting was.

Rhinos and leopards are the rarest of the Big 5 to spot on safari

Rhinos and leopards are the rarest of the Big 5 to spot on safariAll of that changed when I met Max.

After reading Daphne Sheldrick’s book I visited her elephant orphanage in Kenya. Although the main attraction here were the orphaned baby elephants, at the end of the visit I noticed an enclosure separated from the elephants stalls.

Inside was an intimidating bulk of animal – a one-and-a-half-ton rhinoceros. Sensing me, Max, the blind orphaned rhino walked straight towards me.

PETTING A RHINOCEROUSTwo lethal looking horns projected from the front of his head as he turned his body sideways against the steel bars separating me from him.

I reached my hand through the slat. Doubting he could sense my touch through rhino skin that felt dry, gritty, like sandpaper, I began to scratch.

His head sunk incrementally lower and lower toward the ground as his muscles gave way to my massage. And he closed his eyes.

I rubbed around his face, ears, and cheeks. And then he maneuvered his belly towards my hand. Did he really want me to rub his belly?

blind Max asking to be rubbed. photo: Barbara Calvo

blind Max asking to be rubbed. photo: Barbara CalvoYes, he did.

And then I heard it: A long low sigh– a sound that seemed to come from somewhere deep inside.

Was he crying?

What is Max saying? Photo: Barbara Calvo

What is Max saying? Photo: Barbara CalvoFound blind and motherless, Maxwell was brought to the elephant orphanage at the start of 2007. I kept stroking him, and then I started to cry. I wept for my lack of understanding of this magnificent animal, and for all the pain inflicted on his species.

POACHING CRISIS

The news is full of rhino poaching stories. There are an estimated 1,000 rhinos killed annually, and an estimated 30,000 left in the wild.

The poachings have a mafia-like level of sophistication, and the prices fetched ($133 per gram of powdered horn) equal profits rivaled in drug and sex trafficking.

The rhino’s horns are brutally hacked off their faces (fatally wounding the animals) and then shipped to Laos, China, and Vietnam where the horns are used as high-level gifts by governmental officials and other wealthy business people.

Credit: World Rhino Day web site

Credit: World Rhino Day web site

The crazy thing is, the horns are made of keratin, the same substance of our finger and toenails.

Good News for RhinoOn all my Kenya safari itineraries I include the Lewa Wildlife Conservancy. The place started as a rhino sanctuary and has become a model of conservation worldwide. Working with the local communities there has resulted been zero poaching in the area for many years.

When I told Max’s caretakers at the Sheldrick orphanage that Max seemed to be crying while I caressed him, they replied, “No, no, he wasn’t crying. He was happy,” they said.

“He loves to be touched and he especially loves to be tickled.”

Rhinos love to be tickled. And why wouldn’t they?

****

WHAT YOU CAN DO:

Help save rhino. Donate to Saving Wild and we will send your money to the best organizations helping to save the rhino from extinction. To make a donation, go here.

The post appeared first on Saving Wild.

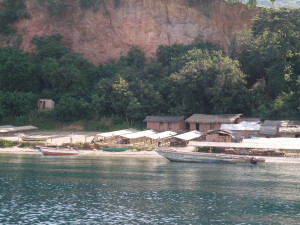

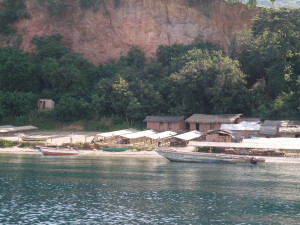

October 6, 2021

Greeting Jane Goodall’s Chimpanzees of Gombe

Our boat lands on the sandy shores of Gombe Stream National Park where 26 year old Jane Goodall and her mother Vanne first arrived in July, 1960.

Traveling to Gombe by boat.

Traveling to Gombe by boat.Soon afterwards Dr. Jane’s ground breaking behavioral research on chimpanzees (under the direction of Dr. Louis Leakey), aided by her patience, tenacity, and love for animals catapulted her to the most admired and recognizable face of conservation.

If you’re a fan of Jane Goodall (and who isn’t) you’ve probably wondered what it would have been like to wander the forest of Gombe in search of the chimpanzees, just like Jane did. You may even have hopes of visiting Gombe, Tanzania’s smallest park, someday.

During my work as the Africa Adventure Specialist for the Jane Goodall Institute I was in charge of designing and leading safaris for members of her organization, and my safari itineraries always included a trip to Gombe to see the world’s most famous chimpanzees.

None of us can be in Jane’s shoes, to feel what she felt as a young woman walking through Gombe’s now 30 square miles of forest, living in a tent on the eastern shore of Lake Tanganyika. But every time I visit Gombe I try. And now you can too.

Keep reading for a glimpse of what it takes to hike in Gombe to see the chimps.

~~~~~

The World of Gombe’s Chimps

A deafening scream engulfs the jungle, spurring a troop of colobus monkeys into action. Away from the danger they fly like trapeze artists through the treetops above us.

“The chimps are very close,” Emmiti, our trekking guide, tells the cadre of eight excited tourists on this safari.

For almost an hour we have been following Emmiti along forest trails worn clear by the comings and goings of bushbuck, bush pigs, chimps and baboons. He points out broken blossoms and small yellow fruits “related to nutmeg” with large black seeds coated in red – “scraps from the chimps feasting in the evergreen canopy above us.”

Baboon with baby.

Baboon with baby.We hear the chimps but can’t see them

We hear a scream, followed by rustling branches as the chimpanzees advance upslope ahead of us, out of view.

The ape’s occasional ear-splitting yells serve as beacons to locate them. Through a walky-talky Emmiti stays in constant communication with researchers who enter the forest at dawn searching for leaf-laden beds the chimps have made and slept in the previous night. Once the chimps are found, the researchers follow (and record) the animal’s movements the rest of the day, continuing Dr. Jane’s initial research, and making this the longest consecutive study done on any wild animal in the world.

“They’re moving fast but we are near,” Emmitti’s says, and quickens our pace forward. We reach an area now named Jane’s Peak, the high plateau from which young Jane, using an old pair of hand me down binoculars, scanned the forest each day looking for her research subjects.

Overlooking Jane’s Peak.

Overlooking Jane’s Peak.“The park has more than 200 bird species, and 11 species of snakes,” Emmiti says, stopping near a trickling stream edged by ferns. By now we’ve been hiking for 1½ hours. A couple of us lean wearily against the soft body of a gigantic fig tree with rounded leaves the size of frisbees. “There are also leopards here,” he says proudly, “but I’ve never seen one.”

Determined to intersect the apes, Emmiti leads us off the trail, onto a steep incline. For thirty minutes we bush whack upwards through a dense tangled world of vines and thin-branched shrubs. With each step we test the ground, searching for dirt that won’t give way underfoot, and unwrap hostile vines from our arms and legs.

“They are moving fast but we are close now,” Emmiti says as he passes by me on the side of the hill, spread eagle, holding onto a thin twig sticking out of the ground.

I look over at our intrepid group, also leaning against the hill, shirts stained dark, beads of sweat dripping down their faces.

“I don’t think we can go on like this for much longer,” I whisper to Emmiti so the others don’t hear. “We need to stop.”

“Does anyone want to turn back?” I ask.

Water bottles held to their mouths, everyone shakes their head, No.

“OK. Let’s just rest here for a few more minutes.”

Everyone shakes their head, Yes.

The chirps of unseen birds join the whirr and buzz of cicadas and other insects, but the chimps have gone silent.

Time-lapsed Discovery Channel images enter my mind.

Humid, dense riverine forests like these are masters of conversion. Everything the forest produces – fallen leaves, animal bones, butterfly wings, and anything that stops moving long enough, will be transformed to rich compost. I envision army ants devouring my flesh, one small chunk at a time, and strangler vines, covering their ‘prey’ in a cocoon, converting it back to the earth.

How long would we have to stay here before the conversion back to the earth begins, I wonder?

Emmiti interrupts my reverie. “Everyone ready,” he says more as a statement than a question. I think I detect frustration in his voice. Has our need to rest sealed our fate? Have the chimps moved too far away now?

I unwrap the mottled green vine that has taken my left leg as hostage, swat a mosquito on my cheek, and move up the hill behind Emmiti.

Five minutes into our steady upward pace Emmiti announces for the fourth time today, “We are very near.”

Susan gives me a look, really?

I wonder what Emmiti’s definition of ‘very close’ is. We haven’t heard the chimps for the past twenty minutes and I’ve mentally prepared myself for failure. This will be the first time in the eight years I’ve organized tourist trips to Gombe that our group won’t see the infamous primates.

Emmiti slows his fervent pace, stopping along a flat trail on a ridge near the top of the hill. He turns toward us, his forefinger placed over his mouth. “Shush”, each of us commands the person behind as we cluster together.

I’m dubious. Then I sense something. The forest is alive with subdued movement. Through the dappled shadows I see them. Twenty-four chimpanzees, the largest troop I’ve ever witnessed, surround us.

“They’ve taken a break from feeding, and we’re in their resting area,” Emmiti says. “We’re lucky.”

Chimps surround us.

Chimps surround us.We each sit on a tree stump or patch of ground void of army ants. Black-furred bodies climb tree trunks, hanging from branches with one hand, eyeballing our group. Passing us on all fours a group of five chimps are so near I could touch them. I think of Jane Goodall when she first made contact with David Greybeard, one of her most memorable moments. She reached out her hand to him in an unprecedented gesture, and he responded in turn.

I want to hold hands with a chimp I thought. But it’s too dangerous. We share 98% of our DNA with these great apes, our closest living relatives, making disease easily spreadable between our two species. Touching them can kill them. Tourists have to have a series of vaccinations when signing up for this adventure, and are told to suppress any coughing or sneezing while in the presence of the wild chimps.

A few chimpanzees start yelling like a gaggle of children on a playground. Through my binoculars I see the source of their excitement – a six-inch thick gray python curled in the grass. The chimps scream with protest and warning while pelting their target with sticks and rocks.

Sitting on a log near me, a young whimpering male displays himself. “He can’t find his mother in all the confusion,” one of the researchers tells us, “he’s feeling insecure.”

After the commotion dies down, tiny baby apes swing precariously around older females (mothers?) resting in wide tree-notches. Adolescents chase each other around their human visitors. They are used to being watched.

I lay down on the leafy ground mimicking a chimp twenty feet from me. Our eyes meet and I imagine living full time in his world. I try to imagine Dr. Jane living here with little comforts or human companionship, day after day searching for the chimps, just like we have done today.

I’m full of admiration and envy.

The post Greeting Jane Goodall’s Chimpanzees of Gombe appeared first on Saving Wild.

Meeting Jane Goodall’s Chimpanzees of Gombe

Our boat lands on the sandy shores of Gombe Stream National Park where 26 year old Jane Goodall and her mother Vanne first arrived in July, 1960.

Traveling to Gombe by boat.

Traveling to Gombe by boat.Soon afterwards Dr. Jane’s ground breaking behavioral research on chimpanzees (under the direction of Dr. Louis Leakey), aided by her patience, tenacity, and love for animals catapulted her to the most admired and recognizable face of conservation.

If you’re a fan of Jane Goodall (and who isn’t) you’ve probably wondered what it would have been like to wander the forest of Gombe in search of the chimpanzees, just like Jane did. You may even have hopes of visiting Gombe, Tanzania’s smallest park, someday.

During my work as the Africa Adventure Specialist for the Jane Goodall Institute I was in charge of designing and leading safaris for members of her organization, and my safari itineraries always included a trip to Gombe to see the world’s most famous chimpanzees.

None of us can be in Jane’s shoes, to feel what she felt as a young woman walking through Gombe’s now 30 square miles of forest, living in a tent on the eastern shore of Lake Tanganyika. But every time I visit Gombe I try. And now you can too.

Keep reading for a glimpse of what it takes to hike in Gombe to see the chimps.

~~~~~

The World of Gombe’s Chimps

A deafening scream engulfs the jungle, spurring a troop of colobus monkeys into action. Away from the danger they fly like trapeze artists through the treetops above us.

“The chimps are very close,” Emmiti, our trekking guide, tells the cadre of eight excited tourists on this safari.

For almost an hour we have been following Emmiti along forest trails worn clear by the comings and goings of bushbuck, bush pigs, chimps and baboons. He points out broken blossoms and small yellow fruits “related to nutmeg” with large black seeds coated in red – “scraps from the chimps feasting in the evergreen canopy above us.”

Baboon with baby.

Baboon with baby.We hear the chimps but can’t see them

We hear a scream, followed by rustling branches as the chimpanzees advance upslope ahead of us, out of view.

The ape’s occasional ear-splitting yells serve as beacons to locate them. Through a walky-talky Emmiti stays in constant communication with researchers who enter the forest at dawn searching for leaf-laden beds the chimps have made and slept in the previous night. Once the chimps are found, the researchers follow (and record) the animal’s movements the rest of the day, continuing Dr. Jane’s initial research, and making this the longest consecutive study done on any wild animal in the world.

“They’re moving fast but we are near,” Emmitti’s says, and quickens our pace forward. We reach an area now named Jane’s Peak, the high plateau from which young Jane, using an old pair of hand me down binoculars, scanned the forest each day looking for her research subjects.

Overlooking Jane’s Peak.

Overlooking Jane’s Peak.“The park has more than 200 bird species, and 11 species of snakes,” Emmiti says, stopping near a trickling stream edged by ferns. By now we’ve been hiking for 1½ hours. A couple of us lean wearily against the soft body of a gigantic fig tree with rounded leaves the size of frisbees. “There are also leopards here,” he says proudly, “but I’ve never seen one.”

Determined to intersect the apes, Emmiti leads us off the trail, onto a steep incline. For thirty minutes we bush whack upwards through a dense tangled world of vines and thin-branched shrubs. With each step we test the ground, searching for dirt that won’t give way underfoot, and unwrap hostile vines from our arms and legs.

“They are moving fast but we are close now,” Emmiti says as he passes by me on the side of the hill, spread eagle, holding onto a thin twig sticking out of the ground.

I look over at our intrepid group, also leaning against the hill, shirts stained dark, beads of sweat dripping down their faces.

“I don’t think we can go on like this for much longer,” I whisper to Emmiti so the others don’t hear. “We need to stop.”

“Does anyone want to turn back?” I ask.

Water bottles held to their mouths, everyone shakes their head, No.

“OK. Let’s just rest here for a few more minutes.”

Everyone shakes their head, Yes.

The chirps of unseen birds join the whirr and buzz of cicadas and other insects, but the chimps have gone silent.

Time-lapsed Discovery Channel images enter my mind.

Humid, dense riverine forests like these are masters of conversion. Everything the forest produces – fallen leaves, animal bones, butterfly wings, and anything that stops moving long enough, will be transformed to rich compost. I envision army ants devouring my flesh, one small chunk at a time, and strangler vines, covering their ‘prey’ in a cocoon, converting it back to the earth.

How long would we have to stay here before the conversion back to the earth begins, I wonder?

Emmiti interrupts my reverie. “Everyone ready,” he says more as a statement than a question. I think I detect frustration in his voice. Has our need to rest sealed our fate? Have the chimps moved too far away now?

I unwrap the mottled green vine that has taken my left leg as hostage, swat a mosquito on my cheek, and move up the hill behind Emmiti.

Five minutes into our steady upward pace Emmiti announces for the fourth time today, “We are very near.”

Susan gives me a look, really?

I wonder what Emmiti’s definition of ‘very close’ is. We haven’t heard the chimps for the past twenty minutes and I’ve mentally prepared myself for failure. This will be the first time in the eight years I’ve organized tourist trips to Gombe that our group won’t see the infamous primates.

Emmiti slows his fervent pace, stopping along a flat trail on a ridge near the top of the hill. He turns toward us, his forefinger placed over his mouth. “Shush”, each of us commands the person behind as we cluster together.

I’m dubious. Then I sense something. The forest is alive with subdued movement. Through the dappled shadows I see them. Twenty-four chimpanzees, the largest troop I’ve ever witnessed, surround us.

“They’ve taken a break from feeding, and we’re in their resting area,” Emmiti says. “We’re lucky.”

Chimps surround us.

Chimps surround us.We each sit on a tree stump or patch of ground void of army ants. Black-furred bodies climb tree trunks, hanging from branches with one hand, eyeballing our group. Passing us on all fours a group of five chimps are so near I could touch them. I think of Jane Goodall when she first made contact with David Greybeard, one of her most memorable moments. She reached out her hand to him in an unprecedented gesture, and he responded in turn.

I want to hold hands with a chimp I thought. But it’s too dangerous. We share 98% of our DNA with these great apes, our closest living relatives, making disease easily spreadable between our two species. Touching them can kill them. Tourists have to have a series of vaccinations when signing up for this adventure, and are told to suppress any coughing or sneezing while in the presence of the wild chimps.

A few chimpanzees start yelling like a gaggle of children on a playground. Through my binoculars I see the source of their excitement – a six-inch thick gray python curled in the grass. The chimps scream with protest and warning while pelting their target with sticks and rocks.

Sitting on a log near me, a young whimpering male displays himself. “He can’t find his mother in all the confusion,” one of the researchers tells us, “he’s feeling insecure.”

After the commotion dies down, tiny baby apes swing precariously around older females (mothers?) resting in wide tree-notches. Adolescents chase each other around their human visitors. They are used to being watched.

I lay down on the leafy ground mimicking a chimp twenty feet from me. Our eyes meet and I imagine living full time in his world. I try to imagine Dr. Jane living here with little comforts or human companionship, day after day searching for the chimps, just like we have done today.

I’m full of admiration and envy.

The post Meeting Jane Goodall’s Chimpanzees of Gombe appeared first on Saving Wild.