M.K. Hobson's Blog, page 8

May 1, 2012

A story about pie

There was one house in particular where I was turned down that evening. The porch windows opened on the dining room, and through them I saw a man eating pie–a big meat-pie. I stood in the open door, and while he talked with me, he went on eating. He was prosperous, and out of his prosperity had been bred resentment against his less fortunate brothers.

There was one house in particular where I was turned down that evening. The porch windows opened on the dining room, and through them I saw a man eating pie–a big meat-pie. I stood in the open door, and while he talked with me, he went on eating. He was prosperous, and out of his prosperity had been bred resentment against his less fortunate brothers.

He cut short my request for something to eat, snapping out, “I don’t believe you want to work.”

Now this was irrelevant. I hadn’t said anything about work. The topic of conversation I had introduced was “food.” In fact, I didn’t want to work. I wanted to take the westbound overland that night.

“You wouldn’t work if you had a chance,” he bullied.

I glanced at his meek-faced wife, and knew that but for the presence of this Cerberus I’d have a whack at that meat-pie myself. But Cerberus sopped himself in the pie, and I saw that I must placate him if I were to get a share of it. So I sighed to myself and accepted his work-morality.

“Of course I want work,” I bluffed.

“Don’t believe it,” he snorted.

“Try me,” I answered, warming to the bluff.

“All right,” he said. “Come to the corner of blank and blank streets”–(I have forgotten the address)–”to-morrow morning. You know where that burned building is, and I’ll put you to work tossing bricks.”

“All right, sir; I’ll be there.”

He grunted and went on eating. I waited. After a couple of minutes he looked up with an I-thought-you-were-gone expression on his face, and demanded:–

“Well?”

“I … I am waiting for something to eat,” I said gently.

“I knew you wouldn’t work!” he roared.

He was right, of course; but his conclusion must have been reached by mind-reading, for his logic wouldn’t bear it out. But the beggar at the door must be humble, so I accepted his logic as I had accepted his morality.

“You see, I am now hungry,” I said still gently. “To-morrow morning I shall be hungrier. Think how hungry I shall be when I have tossed bricks all day without anything to eat. Now if you will give me something to eat, I’ll be in great shape for those bricks.”

He gravely considered my plea, at the same time going on eating, while his wife nearly trembled into propitiatory speech, but refrained.

“I’ll tell you what I’ll do,” he said between mouthfuls. “You come to work to-morrow, and in the middle of the day I’ll advance you enough for your dinner. That will show whether you are in earnest or not.”

“In the meantime–” I began; but he interrupted.

“If I gave you something to eat now, I’d never see you again. Oh, I know your kind. Look at me. I owe no man. I have never descended so low as to ask any one for food. I have always earned my food. The trouble with you is that you are idle and dissolute. I can see it in your face. I have worked and been honest. I have made myself what I am. And you can do the same, if you work and are honest.”

“Like you?” I queried. Alas, no ray of humor had ever penetrated the sombre work-sodden soul of that man.

“Yes, like me,” he answered.

“All of us?” I queried.

“Yes, all of you,” he answered, conviction vibrating in his voice.

“But if we all became like you,” I said, “allow me to point out that there’d be nobody to toss bricks for you.”

I swear there was a flicker of a smile in his wife’s eye. As for him, he was aghast–but whether at the awful possibility of a reformed humanity that would not enable him to get anybody to toss bricks for him, or at my impudence, I shall never know.

“I’ll not waste words on you,” he roared. “Get out of here, you ungrateful whelp!”

I scraped my feet to advertise my intention of going, and queried:–

“And I don’t get anything to eat?”

He arose suddenly to his feet. He was a large man. I was a stranger in a strange land, and John Law was looking for me. I went away hurriedly. “But why ungrateful?” I asked myself as I slammed his gate. “What in the dickens did he give me to be ungrateful about?” I looked back. I could still see him through the window. He had returned to his pie.

—From “The Road” by Jack London, 1907

The Wobblies: A Brief History

“The working class and the employing class have nothing in common. There can be no peace so long as hunger and want are found among millions of working people and the few, who make up the employing class, have all the good things of life.

Between these two classes a struggle must go on until the workers of the world organize as a class, take possession of the earth and the machinery of production, and abolish the wage system.”

—from the Preamble to the IWW Constitution

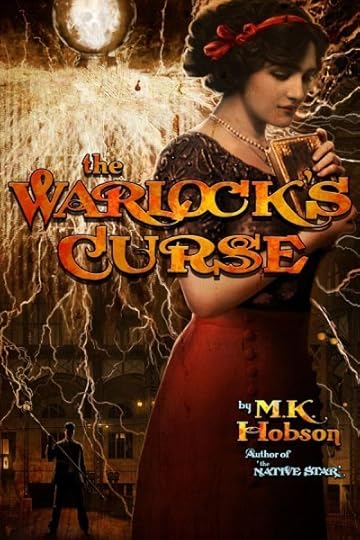

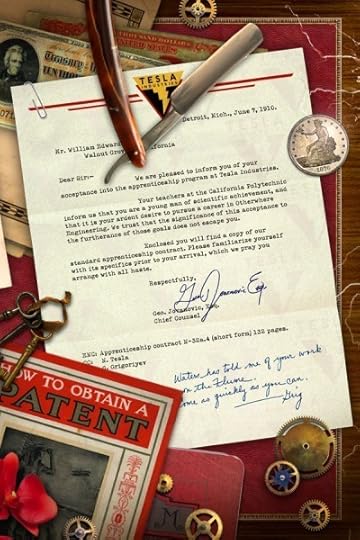

In THE WARLOCK’S CURSE, one of my favorite characters is Harley Briar, a labor organizer with the Detroit IWW. When he’s not rallying the workers at the “Big Three” magical factories, he haunts the so-called “slave markets,” where the unemployed gather to seek work despite the ruinous placement fees charged by the “sharks.” As the life of my main character (Will Edwards) devolves into chaos and disorder, Briar ultimately becomes his guide and mentor through a very unsettled time in American history.

Because I think Briar kicks ass all up and down Grand River Avenue, and in honor of International Worker’s Day, I thought I’d write a bit about the IWW—or, as they’re better known, the Wobblies.

Ancestry

The first labor unions in the United States—craft or trade unions—had their roots in the old guild system. They were federations of workers united by a common profession or craft, such as cigarmakers, leatherworkers, or typesetters. In THE NATIVE STAR, the Witches’ Friendly Society (for which Penelope Pendennis worked as an union representative) was a craft union. (You will, I trust, pardon the pun.)

Members of these kinds of unions possessed specialized skills, usually developed through lengthy apprenticeships. Their bargaining power came from the fact that they were difficult workers to replace.

The foreign-born workers flooding into the new mass-production factories, on the other hand, were not difficult to replace. In fact, with thousands of hungry new immigrants continuing to arrive on America’s shores, they were becoming easier to replace by the day. Workers like these required a whole new kind of union—an industrial union.

In an industrial union, all workers in the same industry—regardless of skill or trade—were organized into one collective unit. This allowed the unskilled workers to leverage the skilled workers’ greater bargaining power. But organizing these two classes of labor into a unified whole wasn’t easy. Convincing the skilled workers that they should be concerned with the fate of their comrades was a hard sell—as was convincing the lower-paid workers that the interests of their higher-paid brethren weren’t far more closely aligned with the bosses’ than with their own.

The Knights of Labor, established in 1869, were one of the earliest industrial unions.They promoted “the social and cultural uplift of the workingman [and] rejected Socialism and radicalism.” They had some notable victories (they are largely to thank for the 8 hour work day) and suffered some notable setbacks. The infamous Haymarket Massacre, which we commemorate today, occurred during a strike led by the Knights in 1886. (As an interesting side-note, the Knights did not want to see May 1 enshrined as the official “Labor Day,” fearing it would become a commemoration of the violence and not the principles behind it. They instead favored the current date in September.)

The Knights of Labor, established in 1869, were one of the earliest industrial unions.They promoted “the social and cultural uplift of the workingman [and] rejected Socialism and radicalism.” They had some notable victories (they are largely to thank for the 8 hour work day) and suffered some notable setbacks. The infamous Haymarket Massacre, which we commemorate today, occurred during a strike led by the Knights in 1886. (As an interesting side-note, the Knights did not want to see May 1 enshrined as the official “Labor Day,” fearing it would become a commemoration of the violence and not the principles behind it. They instead favored the current date in September.)

By 1900, however, plagued by autocratic structure, mismanagement, and unsuccessful strikes, the Knights of Labor had all but disbanded. The remaining faithful—including the majority of New York City’s District Assembly 49—joined the Industrial Workers of the World at its founding convention in Chicago in 1905.

Birth

“Syndicalism: an economic system proposed as a replacement for capitalism and an alternative to state socialism, which uses federations of collectivised trade unions or industrial unions. It is a form of socialist economic corporatism that advocates interest aggregation of multiple non-competitive categorised units to negotiate and manage an economy.”

—Melvyn Dubofsky, “We Shall Be All: A History of the Industrial Workers of the World”

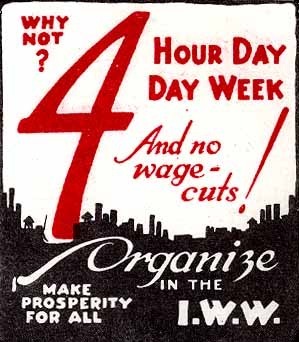

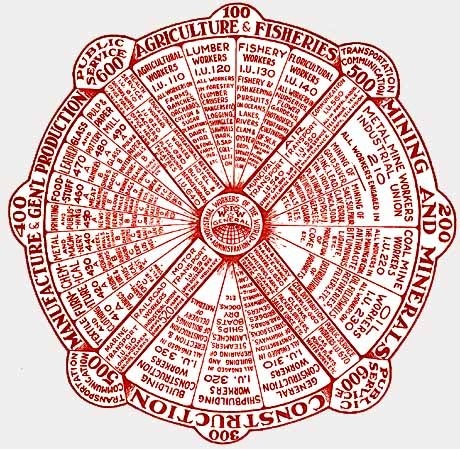

Mixing syndicalist philosophy, anarchist ideals, and Marxist ideological principles, the Industrial Workers of the World brought a fresh revolutionary zeal combined with a keen sense of propaganda. Disdaining the conservative motto “a fair day’s work for a fair day’s wage” that had guided the English working-class movement since the mid-1800s, they advocated instead for the wholesale abolition of the wage system. Their ultimate goal was to combine the American working class (and eventually wage earners worldwide) into “one big union” composed of discrete industrial departments, as outlined in Father Haggerty’s famous “Wheel of Fortune“:

The wheel has been slightly amended over the years. Three new Industrial Unions were added since this graphic was produced: Data Storage and Retrieval Workers Industrial Union 570 (since combined with IU 560); Household Service Workers Industrial Union 680; and Sex Trade Workers Industrial Union 690

These departments were designed to act as syndicalist shadows of American capitalism, so that after the revolution they could quickly step forward to govern the workers’ commonwealth.

Having evolved from the Knights of Labor and organizations like them, the Wobblies took many important lessons from their predecessors. Like the Knights (who frequently included music in their regular meetings and encouraged local members to write and perform their work) the Wobblies recognized the power of the protest song (which would be taken to famous heights by the labor troubador Joe Hill.)

And though the the Knights of Labor had a problematic track record when it came to inclusiveness (they were strong supporters of the Chinese Exclusion Act, and were responsible for race riots that resulted in the deaths of about 28 Chinese Americans in the Rock Springs massacre in Wyoming, and an estimated 50 African-American sugar-cane laborers in the 1887 Thibodaux massacre in Louisiana) they did (after 1878) accept women and blacks as members, and advocated for their admission into local assemblies. The Wobblies significantly expanded upon these early efforts, and were strong advocates for the rights of the disenfranchised.

Adolescence

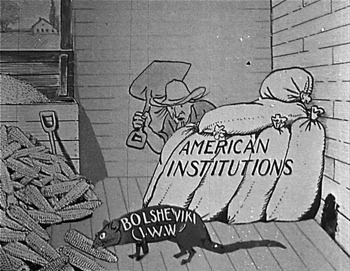

“Never attracting more than 5% of all trade unionists, the IWW looks like a grandiose failure—though in its heyday it was feared as a sinister plot, hatched by foreigners, anarchists, and Bolsheviks, against the American way of life.”

—Patrick Renshaw, ”The Wobblies: The Story of the IWW and Syndicalism in the United States”

The IWWs heyday was between 1905 to 1924. But even during that period, the IWW’s membership rarely exceeded 100,000, and the movement was constantly beset by factional squabbles.

In the time that THE WARLOCK’S CURSE is set, there existed a distinct (and rancorous) division between the Chicago IWW (the “Red IWW”) and the Detroit IWW (the “Yellow IWW.”) The Chicago wing—more anarchist in tone—entirely rejected political action as a means to emancipate the working class from wage slavery.

In the time that THE WARLOCK’S CURSE is set, there existed a distinct (and rancorous) division between the Chicago IWW (the “Red IWW”) and the Detroit IWW (the “Yellow IWW.”) The Chicago wing—more anarchist in tone—entirely rejected political action as a means to emancipate the working class from wage slavery.

“Dropping pieces of paper into a hole in a box never did achieve emancipation for the working class, and to my thinking it never will,” argued Father Haggerty, maverick Roman Catholic priest and one of the movement’s early leaders.

Socialist firebrand Daniel DeLeon took the opposite view.“Thanks to universal suffrage, the ultimate, bloodless socialist revolution will be achieved at the ballot box.”

Sometimes called “The Pope” for his doctrinaire approach (he once “excommunicated” his own son for daring to question his interpretation of Marx’s Theory of Value) DeLeon advocated a mix of political action coupled with economic organization. At the 1905 convention in Chicago, DeLeon succeeded in having language included in the IWW constitution that recognized the need for the organization to agitate “on the political, as well as on the industrial field … without affiliation with any political party.” But this accommodation was not to last. The language was later removed from the preamble, and DeLeon was formally expelled from the Chicago IWW (after calling proponents of that organization “slum proletarians.”) In response, he formed the rival “Yellow IWW”—who later renamed themselves the Workers’ International Industrial Union (WIIU). The WIIU never conducted a strike of any importance, never claimed a very large membership, and was disbanded in 1925.

Maturity

Despite these internecine squabbles and organizational challenges, the Wobblies played a key role in several significant actions between 1905 and 1917—including the McKees Rocks strike of 1909; the 1912 textile strike in Lawrence, Massachusetts, and the 1913 Paterson silk strike in New Jersey—as well as numerous smaller strikes on the East Coast, in the grain fields of the Plains states, at lawless logging camps and mining towns in the Rocky Mountains, the Far West, and the South. Much of their success during those years came from their masterful employment of propaganda, especially song. The lyrics—which Wobbly folk poets wrote to hymn tunes and the popular melodies of the day—were disseminated through the IWW’s “Little Red Songbook,” and were often sung in the strikers’ native language.

They were “one of the few radical movements ever to possess a sense of humor,” wrote Walter Rideout, a student of the radical literary tradition in the United States. “The IWW was … a revolution with a singing voice.”

“It was the first strike I ever saw which sang,” added Ray Stannard Baker, young Progressive journalist. “I shall not soon forget the curious life, the strange sudden fire of the mingled nationalities at the strike meetings when they broke into song.”

Decline

The wave of xenophobia and war hysteria that resulted from the United States’ entry into WWI had disastrous consequences for radical and socialist groups like the IWW. The organization’s philosophical opposition to war, as well as their largely immigrant membership, made them a lightning-rod for patriotic opprobrium. When the IWW led strikes against wage cuts and soaring wartime profits in Arizona metal mines, the copper trust and local press denounced them (predicably) as “pro-German.” Members lived under constant threat of beatings, deportation, shooting and lynching from self-appointed vigilante groups and “superpatriots.” But it was persecution by local, state and Federal authorities that would, in the long run, prove far more damaging.

The wave of xenophobia and war hysteria that resulted from the United States’ entry into WWI had disastrous consequences for radical and socialist groups like the IWW. The organization’s philosophical opposition to war, as well as their largely immigrant membership, made them a lightning-rod for patriotic opprobrium. When the IWW led strikes against wage cuts and soaring wartime profits in Arizona metal mines, the copper trust and local press denounced them (predicably) as “pro-German.” Members lived under constant threat of beatings, deportation, shooting and lynching from self-appointed vigilante groups and “superpatriots.” But it was persecution by local, state and Federal authorities that would, in the long run, prove far more damaging.

On September 5, 1917, the Department of Justice conducted simultaneous raids on 48 IWW Local halls across the country, seizing five tons of letters and other documents. The seized materials formed the basis of an indictment by the Grand Jury of the United States Federal Court in Illinois that followed on September 28. The Grand Jury charged 165 IWW leaders on five counts:

Using force to “prevent, hinder, and delay” the execution of eleven different Acts of Congress and Presidental Proclamations covering the war program;

Conspiracy to “injure, oppress, threaten, and intimidate” those who wished to enjoy the Constitutional right and privilege of executing contracts without interference;

Conspiracy to procure people to refuse to register for military service and encourage desertion from the armed forces;

Conspiracy to cause military insubordination; and

Conspiracy to defraud employers

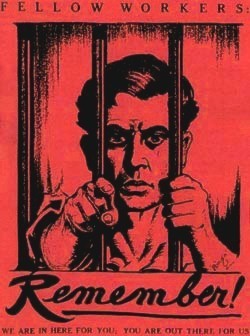

Given the prevailing political climate, it seemed clear that the indicted Wobblies could expect little more than a judicial railroading. Elizabeth Gurley Flynn (an organizer for the IWW in its early years who had been expelled in 1916 for “lack of solidarity”) advocated that indicted members resist arrest. IWW leadership, however, took a different view. Secretary-treasurer “Big Bill Haywood” saw the impending trial as an opportunity to spread IWW propaganda, and ordered all indicted members to submit to arrest. (Of course, when it came time for “Big Bill” to go to jail, he skipped bail and fled to Russia, where he would live out the rest of his days. After his death, his partial remains were ultimately interred in the Kremlin alongside revolutionary journalist John Reed’s.)

The arrested Wobblies—101 of them—spent almost seven months awaiting trial in the “verminous” Cook County jail in Chicago. The trial opened on April 1, 1918, and continued through August. After five months in court hearing evidence which ran to a million words, the jury reached their verdict on all the separate cases in less than an hour, finding all the defendants guilty. Sentences of up to 35 years were handed out, along with total fines amounting to over $2.5 million. Even in the face of this crushing defeat, the Wobblies did not entirely lose their sense of humor. Philadelphia waterfront workers’ leader Ben Fletcher cracked, “Judge Landis has been using bad English today—his sentences are too long.”

The government did not stop with this victory. The Deportation Act of 1918 gave President Wilson’s Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer sweeping rights to launch an unprecedented series of attacks on radical and socialist groups across the country. These notorious and violent “Palmer Raids” resulted in the summary deportation of nearly 250 people, including anarchists Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman. During one of these Palmer Raids on an IWW office, the Feds even confiscated of Joe Hill‘s ashes. (They would not be recovered until the late 1980s, under the Freedom of Information Act.) The Palmer Raids were completely unconstitutional—even J. Edgar Hoover, Palmer’s assistant at the time, admitted that—but they represented the very first flowering of the Red Scare that would come to dominate American politics in the decades to come.

Demise

After 1917, with most of the IWW leadership in jail serving lengthy terms, the Wobblies were outflanked on the extreme left of the political spectrum by the Communists, who—after the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917—had become the new focus for the world revolutionary cause. The IWW soon found itself split between three rival factions—the Communists (who wanted the IWW to merge into the Red International of Labor Unions) the anarchists (who wished to remain completely politically unaffiliated), and the traditionalists (who wanted the organization to carry on as it always had.) In 1923, when the last of the Wobblies jailed in 1918 were released by President Coolidge after a successful amnesty campaign, the prisoners emerged to find an IWW that was much different than it had been just a few years earlier. Riven with dissention, the final schism occurred at the union’s convention in 1924 when the organization split roughly along Communist and anti-Communist lines.

After 1917, with most of the IWW leadership in jail serving lengthy terms, the Wobblies were outflanked on the extreme left of the political spectrum by the Communists, who—after the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917—had become the new focus for the world revolutionary cause. The IWW soon found itself split between three rival factions—the Communists (who wanted the IWW to merge into the Red International of Labor Unions) the anarchists (who wished to remain completely politically unaffiliated), and the traditionalists (who wanted the organization to carry on as it always had.) In 1923, when the last of the Wobblies jailed in 1918 were released by President Coolidge after a successful amnesty campaign, the prisoners emerged to find an IWW that was much different than it had been just a few years earlier. Riven with dissention, the final schism occurred at the union’s convention in 1924 when the organization split roughly along Communist and anti-Communist lines.

Bardo

By the 1930s, with their membership reduced to a bare minimum, much of the work that the IWW had pioneered was taken over by the CIO. CIO leaders borrowed many strike techniques first used by the Wobblies as they assumed the task of organizing workers on an industrial rather than a craft basis. And the political climate that the CIO operated under ensured them far greater success—under the New Deal, unionization was protected by law. The CIO’s focus on improving living and working conditions for its members—instead of the larger goal of revolution—also won it greater support. And as the demographics of the membership shifted (with the predominantly immigrant membership of the 1910s replaced from the 1930s onward by their American-born children) the CIO found the task of organization easier thanks to greater commonalities of language and cultural assimilation.

Rebirth

The IWW is still in existence today, and since the early 1990s has been experiencing a renewed growth in membership and activity. Recent actions have included General Strikes in Oakland and Wisconsin, as well as the organization of workers in food service industries such as Jimmy John’s, Pizza Hut, and Starbucks. With their support of the Occupy Wall Street movement, one can only hope that the 21st century will be kinder to the Wobblies than the 20th.

April 24, 2012

Puffballs of DOOM

OK, seriously, the next video I’m going to post is of feeding time in the Puppy Dungeon. Because you all think that the puppies are cute soft sweet little puffballs, but that’s because you’ve never seen them at feeding time. Sugar comes into the puppy box, lays down with a weary sigh, and the puppies transform from a peacefully sleeping little fur pile into a ravenous mob. All they need are little pitchforks. The little blighters can’t even walk, but when it comes time to eat, suddenly they can RUN. They’re stepping all over each other, climbing over Sugar’s head, trying to tunnel beneath her. It’s kind of terrifying, actually, like watching piranhas feed on a cow who’s had the misfortune to wade into the wrong Amazonian tributary. No wonder Sugar is starting to spend more time out of the puppy box.

OK, seriously, the next video I’m going to post is of feeding time in the Puppy Dungeon. Because you all think that the puppies are cute soft sweet little puffballs, but that’s because you’ve never seen them at feeding time. Sugar comes into the puppy box, lays down with a weary sigh, and the puppies transform from a peacefully sleeping little fur pile into a ravenous mob. All they need are little pitchforks. The little blighters can’t even walk, but when it comes time to eat, suddenly they can RUN. They’re stepping all over each other, climbing over Sugar’s head, trying to tunnel beneath her. It’s kind of terrifying, actually, like watching piranhas feed on a cow who’s had the misfortune to wade into the wrong Amazonian tributary. No wonder Sugar is starting to spend more time out of the puppy box.

April 21, 2012

Puppies sur l’herbe

So as the day was gorgeous and sunny we spread out a blanket so the pups & mom could get some fresh air and bit of a picnic. Some adorable neighbor kids wandered by. A delightful time was had by all!

[View with PicLens]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

12►

April 20, 2012

Three tips for a (spiritually) successful Kickstarter

So in preparing for my Kickstarter, I did a lot of reading on strategies to increase my campaign’s chance of success. I sifted through hundreds of marketing tips on how to get the message out on social media channels without being annoying, how important it was to have a kick-ass video (and how to make one), how to choose the right rewards and structure them into tiers that made sense, how to create a budget, how to keep current backers engaged while continuing to attract new ones. In short, I found a crap-ton of great information on how to run a financially successful Kickstarter campaign.

So in preparing for my Kickstarter, I did a lot of reading on strategies to increase my campaign’s chance of success. I sifted through hundreds of marketing tips on how to get the message out on social media channels without being annoying, how important it was to have a kick-ass video (and how to make one), how to choose the right rewards and structure them into tiers that made sense, how to create a budget, how to keep current backers engaged while continuing to attract new ones. In short, I found a crap-ton of great information on how to run a financially successful Kickstarter campaign.

What I did not find, however, was any information on how to run a spiritually successful Kickstarter campaign.

What the bloggers and boosters don’t tell you is that running a Kickstarter comes with a huge number of spiritual risks. While you are welcome to read that word in any way you like, when I use it, it is in reference to my own personal belief structure (Buddhist) which takes the reduction of suffering and the increase of good karma as activities of primary importance. And by the lights of that belief structure, running a Kickstarter is just asking for trouble. Not because you’re asking for support from other human beings—that is an objectively beautiful activity—but it requires poking some very difficult and painful places in one’s soul. (What right have I to ask for help? Why should people give me anything? Why should anyone even care?) And when you start poking those kinds of places on your soul, it can hurt. And when something hurts, that’s when you have to guard yourself most carefully. Because suffering leads to incorrect thought, and incorrect thought leads to incorrect action, and incorrect action leads to more suffering.

In Buddhism, much is made of carefully, actively, and scrupulously attending to one’s own perceptions. That means paying attention, keeping perspective, and not getting hooked by the chattering “monkey mind.” It means remembering that at every moment, every single individual around us is struggling with their own personal brand of “suffering” … whether that’s the painful suffering of hurt or the sweet sadness of a pleasant moment’s passing. By remaining mindful of this, we can approach the world with compassion. And when you approach the world with compassion, that correct thought leads to correct action … which leads to less suffering.

So, taking that approach, here are my three tips for running a spiritually successful Kickstarter:

Whenever you feel panicked (that you won’t make your goal, or that some important blogger won’t mention you, or whatever) meditate on gratitude. Close your eyes, take a deep breath, and think about all the people who’ve already backed you, tweeted about your Kickstarter, shared your link, or helped you in any way. Think about how incredibly kind they were to do so. They didn’t have to, you know. Every action associated with a Kickstarter is an act of kindness.

Whenever you feel stressed (that there’s just too much to do, that you can’t stay on top of it all) meditate on surrender. Surrender is not a concept we Americans like very much. And when it comes to running a Kickstarter, it probably seems somewhat counterintuitive. “Never give up! Never surrender! Push harder!” But I promise you … manic frenzy is really not the energy you want. Take a break. Be brave enough to just let things drift for a while. Go dark on the channels for a while. (And go spend some time with your family. They probably miss you.)

Whenever you feel despair (that maybe people just aren’t getting it, that your passion is just all wrong)—meditate on impermanence. What is true today may not be true tomorrow. Everything can change in an instant — for better or worse. If you are truly passionate about your project (and if you’re doing a Kickstarter, surely you must be) then have faith in that passion. You will find a way, even if it’s not the way you think. And you will find friends to help you.

Here’s the thing. You can’t control if your Kickstarter is going to be a financial success. You just can’t. It’s out of your hands. But whether it’s spiritually successful? That’s entirely in your own hands, and mind, and heart.

April 16, 2012

The Editorial Draft is sent!

I am pleased to announce that this morning, at 6:19 a.m., I sent off the final draft of THE WARLOCK’S CURSE to my development editor, Juliet Ulman! According to my timeline, I should have had it to her on April 1. Well, that day came and went, making a whooshing sound as it passed, and I thought, “Well, at least I’ll get it to her before the Kickstarter launches.” But that didn’t happen either. Oh well, that’s life in the big city. And I used that extra time to make the draft extra good, so hopefully that counts for something when weighed against my timeline defalcation.

I am pleased to announce that this morning, at 6:19 a.m., I sent off the final draft of THE WARLOCK’S CURSE to my development editor, Juliet Ulman! According to my timeline, I should have had it to her on April 1. Well, that day came and went, making a whooshing sound as it passed, and I thought, “Well, at least I’ll get it to her before the Kickstarter launches.” But that didn’t happen either. Oh well, that’s life in the big city. And I used that extra time to make the draft extra good, so hopefully that counts for something when weighed against my timeline defalcation.

I am really proud of this book. I can’t wait to share it with y’all.

April 15, 2012

THE WARLOCK’S CURSE Cover Reveal (for everyone, this time!)

So I gave my Kickstarter backers a sneak peek at these yesterday, but now it’s time to reveal them to the world! Behold, Lee Moyer’s INCREDIBLE cover and back for THE WARLOCK’S CURSE!

Working with Lee on this cover was an intense creative journey. I haven’t had as much fun on a project in years. Lee is funny, courtly, wise and completely wonderful. What I appreciated most was the careful thought he put into the artwork to make it not only a seamless extension of the covers of the first two books, but also a logical evolution. If you haven’t yet read his insightful post about the covers of THE NATIVE STAR and THE HIDDEN GODDESS, you really should check it out.

I couldn’t be more pleased with this cover. And as an author, those have to be about the nicest words one can type. Besides, perhaps, “The End.”

April 14, 2012

THE WARLOCK’S CURSE Cover Reveal!

Lee Moyer’s cover art has been posted to the Super Special Exclusive Bonus Content section of my Website!

Lee Moyer’s cover art has been posted to the Super Special Exclusive Bonus Content section of my Website!

I’ll be publicly revealing the cover (or maybe just bits and pieces of it, if I’m feeling particularly cruel) sometime on Sunday, April 15. At that time, I’ll also be posting about the process Lee and I went through to create it. It was intense, and intensely fun.

So if you’re a Backer, go check it out immediately! And if you’re not a Backer, become one, if for no other reason than to have your socks knocked off by Lee’s incredible artistic genius.

April 13, 2012

My Kickstarter is Live!

And I am already more than half of 1/10th of the way to my goal!

And I am already more than half of 1/10th of the way to my goal!

I was up way too late last night, having a blast. Determined not to stay up until midnight all by myself, I created a special reward for the first 5 backers of my Kickstarter—and they went like hotcakes at a hotcake-eating contest for people hungry for hotcakes. I really like the shirt I created, too. I’m going to have to get one made for myself.

Then I posted my first Backer Update—where I revealed the secret of the presupporter gift—and emailed thank-yous to all my late-night backers. I’m committed to personally thanking everyone who backs this Kickstarter, so if you’re a backer and you haven’t gotten a thank you from me, it’s coming.

Then I went to bed at 1:38 a.m., only to be woken up by the puppy-momma at 3:30 a.m., wanting to go out. And once I’d let her out I couldn’t get back to sleep, so I sat down and worked a bit. I had hoped to get the final draft of the book to my editor BEFORE the Kickstarter launched, but no luck there. On the plus side, though, I’m 100% sure I’ll have it finished this weekend, as I’m really down to the last 15-20 pages of editing.

And that’s all the news that’s fit to print! (Oh, and P.S., since you read all the way to the bottom, here are puppy pix. I know what you really come to this blog for.)

April 12, 2012

More puppy pix!

Mom and babies are settling in to a nice routine. It’s all just sleepin’ & suckin’, sleepin’ & suckin’, all the livelong day. The puppies are adorable, but nowhere near as cute as they’re going to be in a couple of weeks.

[View with PicLens]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]