Randy Ellefson's Blog, page 31

May 31, 2018

How To Create Prairies and Grasslands

Figure 27 Grasslands

These lands are characterized by grass, whether tall, short, or mixed. The taller grass occurs where there’s more rain, resulting in abundant grain crops. The short grass can be less than a few inches tall. In tropical grasslands, sometimes all of the year’s rain occurs within just weeks.

In North America, when the Rocky Mountains rose, they caused a rain shadow that killed the forests for hundreds of miles east of them in the Midwest, resulting in the prairies of the Midwest. For tens of thousands of years, Native Americans periodically burned these grasslands, preventing trees from growing there. This was done to extend the land for their livestock to graze.

Trees will steadily encroach on prairies without the interference of humans or grazing animals, so keep this in mind when placing them. They will exist due to rain shadows. Our species may cause them to remain intact; otherwise, the land will first turn into a savannah and then a forest. We’ll want some nomadic peoples to dwell there, with herds of grazing animals, like the American Indians.

The post How To Create Prairies and Grasslands appeared first on The Art of World Building.

May 29, 2018

Characterizing Forests

This section talks about how to make forests different from each other, including the impact of residents. There are also example descriptions like what you’d want to write about in your files.

The post Characterizing Forests appeared first on The Art of World Building.

May 24, 2018

How to Create Forests

There are more than eight hundred definitions of “forest,” and we’re going to cover them all. I’m kidding, but if you’re like many, you simply write “forest” in your stories and leave it at that. Here’s a chance to be a little more specific and populate a world with different types of forests.

The tree types are covered in more detail in Creating Life (The Art of World Building, #1), but it helps to know the basic types: evergreen (literally green all year), coniferous (needle-like leaves), and deciduous (seasonal loss of leaves, flowers, and fruit ripening). All trees actually lose their leaves but deciduous ones do so all at once in dry or winter seasons. The others lose and replace their leaves continually. Coniferous trees are the tallest in the world, including the redwood, so if we have elves that are living in enormous trees, they are conifers, which also means a single straight trunk.

Forest

Figure 23 Forest

Most of the time, we will indeed want to say a forest is just a forest. Only when choosing something more specific, as defined next, will we need to deviate.

A forest typically has a tree canopy covering 60-100% of the land within it. This allows for some underbrush but not something impenetrable. Half of the Earth’s trees are in the northern temperate zone, though this is partly because there’s so little land in the southern temperate zone. Temperate zones have both evergreen and deciduous forests; evergreens are the most common trees unless it’s very cold temperate, where conifers dominate.

The latitudes between 53-67° (Polar Regions) have boreal forest, which are predominantly coniferous, with some deciduous trees.

Tropical rainforests are found within 10° of the equator and are almost the only kind of forest found there; the trees there are considered evergreens. Jungles are found there as well (see below). Smaller winged creatures can fly beneath the tall tree-canopy of rainforests but might find it difficult to reach the open sky unless a clearing is available. There is very little underbrush due to the canopy preventing sunlight from reaching the ground.

Woodland

Figure 24 Morton Arboretum Woodland in Lisle, Illinois

A woodland has less tree density and therefore less canopy than a forest and is relatively sunny, with only a little shade. Otherwise the tree types are similar to forests. Most people probably think they’re the same as forests and might call them “light forests.” When naming forested areas, “Forest X” vs. “Woods X” can be used interchangeably, regardless of the tree density. In our notes about the area, we might want to specify it’s a woodland.

A woodland will be easier to ride horses or other animals through than a forest or jungle. The sparser underbrush limits ambush opportunities, so an animal or humanoid species we’ve invented and which relies on ambushing prey is less likely to be found here. While animal trails will still exist, the sparse underbrush means life doesn’t need an existing path (created by other animals) quite as much.

Savannah

Figure 25 Savannah

A savannah has virtually no tree canopy despite the trees, which is one reason grass covers the land. This results in more grazing opportunities for animals than in forests. Some people wrongly believe that widely spaced trees indicate a savannah, but some savannahs have more trees per square mile than forests do. Savannahs cover a fifth of the world’s land surface and typically lie in an area between forest and grasslands.

There have been times in human history where we’ve set fire to a savannah on purpose. The goal is to prevent a forest from forming by killing the smaller trees and shrubs, maintaining the open canopy.

Animals that hide in tall grass will use a savannah to their advantage. Some of their prey will be skilled at climbing trees to escape. The lack of underbrush means riding animals or driving a caravan of wagons is easy.

Jungle

Figure 26 Jungle

The term “jungle” is poorly defined in its vernacular usage. It’s basically a very dense forest with enough underbrush to be difficult, if not impossible, to traverse unless we hack our way through. It’s often implied to be in the tropics but needn’t be. This contrasts with rainforests, which have very little underbrush due to the tree canopy that prevents light from reaching the ground. Jungles often border rain forests due to the light at the edge allowing underbrush to grow; we might have to cut our way through a jungle to reach the rain forest. The wildlife in jungles is dependent on where the jungle lies.

If you’re confused as to the difference between jungle and rainforest, that’s partly because the latter term replaced the former. To quote Wikipedia, “Because European explorers initially travelled through tropical rainforests largely by river, the dense, tangled vegetation lining the stream banks gave a misleading impression that such jungle conditions existed throughout the entire forest. As a result, it was wrongly assumed that the entire forest was impenetrable jungle.”

Due to underbrush, a jungle is largely impassable so that even people on foot will have trouble. Horses or other steeds cannot be ridden and might even be abandoned. Creatures who ambush will abound in such conditions.

The post How to Create Forests appeared first on The Art of World Building.

May 21, 2018

How to Create River and Lakes

Rivers flow downhill to other rivers, lakes, or the ocean, but sometimes they dry up first. Other times they fall into a hole in the ground to become underground rivers. They seldom take the shortest route to their destination but simply go downhill, cutting through the softest material. Wide rivers can have a floodplain, which is where all the water goes when a river floods its banks. A floodplain can be many miles wide and have multiple settlements in it.

The age of a river can determine some of its characteristics because the erosion deepens over time. Young rivers like the Brazos River, Trinity River, and Ebro River tend to be steep and fast, with few tributaries but deep rather than broad erosion. Mature rivers like the Mississippi River, Ohio River, and Thames River are less steep, flow more slowly, and have more tributaries, with wider channels. Old rivers are slow, don’t erode much, and have floodplains; examples include the Tigris River, Euphrates River, and Indus River. When adding rivers, we should note their age in our files and consider how to draw them: a nearly straight line suggests a young river while a winding river suggests an old one.

The impact of rivers is mostly felt on settlements, but wide and long rivers have often been the boundary between nations. Keep this in mind when laying them out, for it’s an easy way to decide where one kingdom ends and another begins. There will be many more rivers than the ones we put on the map, so when it comes to drawing, we’re talking about the big ones, like the Mississippi River. Waterways can also impact travel, as we’ll discuss later in the “Travel by Water” chapter.

Lakes

Lakes are found in natural depressions and along the courses of mature rivers, which are moving more slowly than young rivers. Most of them are also in higher latitudes. When deciding a lake exists somewhere, we need no explanation other than that a river flows into it. Sometimes two lakes that are near each other are connected by a strait. Most lakes on Earth are freshwater, but some are not, such as the Dead Sea and Great Salt Lake.

Lakes have natural outflows in the form of rivers or streams, which serve to keep the lake level consistent (excess water drains off). But some lakes don’t and maintain their level via evaporation or underground drainage; we can have a river end in a lake and not continue out the other side. Lakes sometimes vanish quickly, even in a few minutes, if something like an earthquake opens up a hole through which the lake drains into ground water. This is another scenario we can use in our writing if our inhabitants attribute this to something supernatural. Incidentally, Baikal Lake in Russia is the deepest lake on Earth and is over 5,300 feet (1615 meters)—deep enough for a monster, certainly.

There’s no real difference between lakes and ponds and in fact there’s argument about what the difference is, the usual determining factor being size. That said, ponds far outnumber lakes. Geologically speaking, all lakes are temporary because they’ll eventually fill with sediment, a fact which only becomes relevant if we have time-traveling characters who go far into the future and wonder why a lake is gone.

The post How to Create River and Lakes appeared first on The Art of World Building.

May 17, 2018

Characterizing Mountains

Some mountain ranges are only 3-4000 (914 meters) feet tall while others tower above 10,000 (3000 meters). This is a critical difference. Lower mountains are less likely to cause a rain shadow, while taller ones absolutely will; the surrounding terrain is affected for as much as a thousand miles. Travel across a range differs according to how high one must climb to traverse them. Survival conditions deteriorate, too, as some mountains are so high that oxygen deprivation occurs (above 2400 meters or 8000 feet). The increased cold is another factor; it is possible to freeze to death. An underground species like dwarves may tunnel through, as could monsters, to solve this problem.

The ability of flying species, giant birds or dragons, to cross these peaks might also be impacted, particularly if they’re carrying a load, such as our characters. We can narrate that our giant birds can take them as far as those peaks but no farther. The air becomes thinner at higher elevations and even birds struggle to fly over. The additional lift required by something the size of a dragon may preclude it from flying over the highest peaks, except that we like the idea that they’re all powerful, but the point is worth making.

The higher the peaks, the less likely they are traveled, meaning a settlement there might be safer than one at lower altitudes. This will determine how many visitors the place is likely to get and even how receptive the residents are to that. This can work in different ways.

The higher the peaks, the less likely they are traveled, meaning a settlement there might be safer than one at lower altitudes. This will determine how many visitors the place is likely to get and even how receptive the residents are to that. This can work in different ways.

For example, a settlement in high mountains might be rarely visited and therefore suspicious and hostile toward outsiders. Then again, maybe it has no reason to be so hostile because no one poses a threat to it. Perhaps a settlement in smaller mountains is the one that’s very protective and suspicious, refusing admittance to others. We can create different scenarios for each range, making the settlements therein different. Higher altitudes also pose problems with oxygen deprivation and higher mother and infant mortality rates.

Residents

Which species live in each mountain range? It’s likely that the same ones live in every one, but that may depend upon their attitude. I have a species that likes to prey upon other species but which is simultaneously at risk of being preyed upon by others. The result is that, if their prey isn’t present, they tend to not be there either. Some of our species might have massive numbers in the peaks, which they use as a base to amass armies or from which to launch raids.

Another issue is whether we have a species, or more than one, known for tunneling into mountains, like dwarves. They can have underground civilizations that mine for gems and minerals like gold. This can make their lairs desirable for conquest. They may also unearth monstrosities buried deep in the earth and better left undisturbed. Maybe their place has been destroyed as a result, with all manner of ghosts haunting the ruin. Or perhaps they’ve controlled whatever they’ve unleashed and can send it after those who try to conquer them.

Dangerous animals and monsters can also be present and impact travel. Their presence can be known or not. Do our characters prepare for an encounter or try to evade them? Do they assume a certain number of them will be killed before they get through? If the mountains are low enough and our characters can afford aerial flight, maybe it becomes a moot point, unless these creatures can also fly or knock out of the sky anything that does. Then our people must escape alive.

Example Descriptions

Below are two example descriptions similar to those you’ll write for your files.

Forbidden Peaks

These intimidating mountains are shorter than most, being less than 5,000 feet tall, but the stories of evil wizard towers and all manner of monsters have kept most people from entering. Those who do often don’t return or return insane, babbling nonsense about hundred-foot-tall cave trolls, talking trees, and rocks that come alive and chase people. The wizards of Nivera have investigated these rumors and found enough evidence to prove the claims, though they have admitted that only to the royal court in Nivera.

Soaring Peaks

Volcanic in nature, these peaks still rumble with activity so that those nearby have long thought the gods must visit here. The tallest peaks are over 10,000 feet while the average is a couple of thousand less. Heavily forested, they are home to all manner of dragons and other flying creatures, many of them preyed upon by the dragons. The southern pass is inhabited by ogres and goblins, making travel hazardous and the city of Nivera hard to reach or escape. By contrast, the northern pass is well protected, courtesy of castles at either end and a legion of knights.

The post Characterizing Mountains appeared first on The Art of World Building.

May 14, 2018

How to Create Mountains

While laying out land features can be fun, it’s even better when we’ve first reminded ourselves of the possibilities and what they can mean for our world’s inhabitants, our audience, and ourselves. This chapter is a roundup of the salient details world builders should consider. We can start placing items without having outlined a continent or even a coastline, but it’s often better to know where the sea is, to determine plate tectonics, covered in Chapter 3, “Creating a Continent.”

Mountain Ranges

Mountains

Mountains are covered first because their effect on precipitation determines the locations of forests, deserts, and rivers. We all know what a mountain is, but scholars have not agreed on a definition. What this means is that our characters can refer to something as a mountain when it isn’t that tall (less than a thousand feet), so remember this option. The land just needs to stand out from the surrounding area.

Roughly 24% of Earth’s surface is mountainous. Glaciers can create various shapes, including cirques (an amphitheater-like circle) where lakes form. If two parallel glaciers recede and carve parallel valleys, they can leave a row of peaks between them. If three glaciers recede from the same central point, a pyramid-like, sharply pointed peak or glacial horn is formed, like the Matterhorn. While these are interesting, they seldom matter on the large scale for world builders and are instead ideas for characterizing individual peaks our characters have noticed.

The highest mountain discovered in the solar system is Olympus Mons on Mars. Its extreme height (69,459 feet vs. Mount Everest’s 29,035) is due to the absence of tectonic plates on Mars. Land stays over a hot spot indefinitely, causing eruptions and lava flows in the same place, which increases local elevation. By contrast, on Earth, tectonic plates shift land (or ocean) across the hot spots, causing things like a chain of volcanic islands like Hawaii. If we want a truly enormous, standalone mountain on our world, we can decide tectonic plates don’t exist, but this would cause various changes like a potential lack of earthquakes or mountain ranges (and a resulting lack of rain shadows). Such a world might have many very tall, volcanic mountains but few if any ranges.

Such enormous mountains may not be as interesting as they sound. Olympus Mons is so wide, as big as France, that our characters wouldn’t even realize they’re on a mountain if walking on it. If we want something dramatic, than a single, solitary peak is better. Images of Mt. Shasta in California can give you inspiration. While it’s only 14,000 feet, it’s so large compared to its surroundings as to be majestic, and majesty is arguably what we’re after. We don’t need a giant Olympus Mons and its accompanying problems for our world.

Mountain ranges can have peaks formed by different forces, meaning some are volcanic while others aren’t. Several ranges can be back to back; this means one is north-to-south, and where it ends, another north-to-south range begins. To the layman, we sometimes don’t realize this; neither will our audience, but we can give two different names to a range if they’re separated by a pass or a little offset from each other. For example, the Appalachian Mountains include the Blue Ridge Mountains and White Mountains. These are regional names for the same range and are technically the smaller ranges that make up the larger one. If we have a truly long range, a thousand miles or more, it might not be realistic to say it’s a single mountain range. It’s probably several ranges.

Volcanoes

We often speak of volcanoes as being active (they erupt regularly), dormant (it hasn’t erupted in centuries), or extinct (it hasn’t erupted in written history). These distinctions aren’t scientific and a supposedly extinct volcano can erupt again many years after the last time. By human life spans, they’re extinct, but active compared to the planet’s life span. For our purposes, these classifications work, but we can surprise our species by having a supposedly extinct volcano erupt; maybe it’s part of a prophecy.

Some volcanoes on Earth have been erupting continuously for hundreds of years, but these aren’t the explosive ones. We can have our characters believe an evil is ongoing in the world as long as Mount So-And-So is erupting. Or the reverse—a volcano’s been erupting for as long as anyone remembers and then suddenly it stops as foretold, with consequences everyone’s heard of.

A very large eruption of ash can cause a volcanic winter (when the sun is blocked out for a long time). This has caused some of the world’s worst famines and even mass extinctions.

The post How to Create Mountains appeared first on The Art of World Building.

May 10, 2018

Where to Start Creating Continents

Though adding land features is part of the next chapter, making a list of the ones we’d like to include can help us determine how large a continent we need. Our story requirements can also help this. An early decision is hemisphere, as this determines whether hot or cold is north or south. We might also want to know other continents’ direction and distance, as this influences population and more; try not to think of the continent as an island. We should also determine where bays and other water ways are when drawing our map, as this can influence the sovereign powers we place there. I recommend following the steps in the bonus chapter, “Drawing Maps.” We can also start by imagining what powers we’d like in various areas of the land mass and rough ideas on their world view and impact, which can be fleshed out more by following Chapter 6, “Creating a Sovereign Power.” There’s no right or wrong way to start creating a continent because it’s somewhat vague until we start filling it in, so use whatever inspires you to get going.

The post Where to Start Creating Continents appeared first on The Art of World Building.

May 7, 2018

Bays and Islands

This section talks about the difference between many types of water bodies and how knowledge of this can help world builders add variety to their worlds.

The post Bays and Islands appeared first on The Art of World Building.

May 3, 2018

Seas and Oceans

This section talks about the differences between seas and oceans and how world builders should use them.

The post Seas and Oceans appeared first on The Art of World Building.

April 30, 2018

Understanding Plate Tectonics

Understanding plate tectonics will help us add mountain ranges that make sense. A planet surface is composed of an outermost shell of slowly moving plates, which either converge on each other, diverge, or transform. The first two are the motions that create mountains ranges and volcanoes. Most volcanoes occur where two plate boundaries intersect, but some volcanoes exist in the middle of plates due to flaws in the plates; this means we can have a volcano anywhere on our map and no one can tell us otherwise.

There’s a reason the western United States has major earthquakes and volcanoes and the eastern doesn’t. The continental shelf is the area of land that’s underwater just offshore. It is shallow compared to the deeper ocean. On the east coast, the shelf is wide, which means the plate boundary is also far away. By contrast, the west coast’s shelf is narrow, ending just offshore. This means the deep ocean isn’t far away. More importantly, the plate boundary is near the west coast, causing dramatic boundary activity that results in mountains and volcanoes.

Such a situation is true on other continents and is something to consider. If we say that deep water lies just off the coast of a continent, there are probably nearby mountains, some volcanic. We can also approach that in reverse: a coastal mountain range likely has deep water not far from shore. Ship wrecks there will be far under the waves. If we have a water-dwelling, humanoid species, or even sea monsters, they might be found here. Using the U.S. as an example, a giant sea monster is more likely to be encountered near the west coast than the east.

Convergent Boundaries

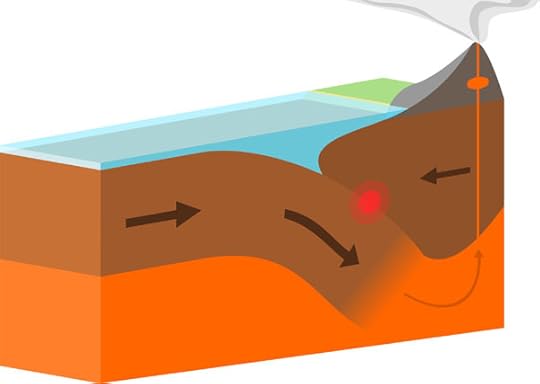

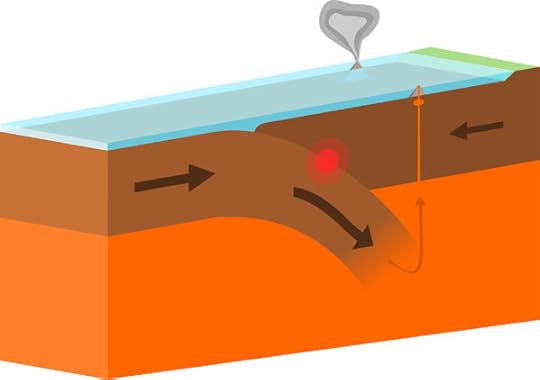

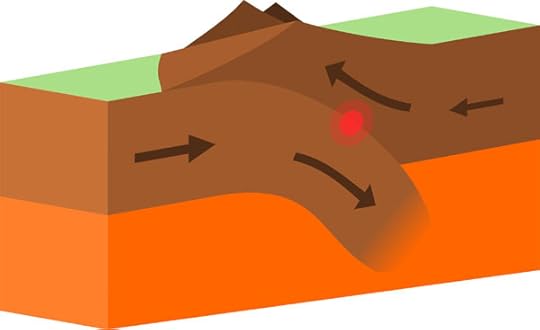

When two plates converge, one destroying the other’s edge, the results can be varied.

If subduction, in which one plate is forced under another, happens at an ocean-to-continent boundary, the ocean plate plunges under the continent, causing a continental mountain range. This range will be parallel to the coast (plates), with volcanoes that are the most explosive.

Figure 22 Continent to Continent Boundary

If subduction happens with two ocean plates, one goes under and causes a chain of volcanoes, which will eventually breach the ocean surface and become land. These volcanic islands will form a subtle arc shape in relation to each other because a planet is a sphere. A deep ocean trench will also form. This can be over two miles below the rest of the ocean floor there. It can also be a hundred miles away. If we have a sea monster we’d like to give a home to, here is where it lives. In a world with sea monsters, a place like Hawaii would be prone to at least one creature; it almost doesn’t make sense for one not to be there.

Figure 21 Ocean to Ocean Boundary

At a continent-to-continent boundary, the plates can converge, fold, and lift, forming very tall mountain ranges with no volcanoes. These will be the tallest ranges on our world, located in the interior of continents.

Figure 20 Ocean to Continent Boundary

Divergent Boundaries

When two plates move away from each other underwater, small volcanoes form, which can result in volcanic islands. When this happens on land, a low area of land can form and then fill with ocean water to create a sea.

The Earth continents were once a super continent that broke apart. Divergent plates caused this. Evidence is apparent just from looking at the globe, as South America and Africa look like adjacent puzzle pieces. We can use the same idea for our continents, a small detail that may impress an audience if they notice.

Transform Boundaries

Transform boundaries means two plates grind past each other without destroying either. These plates sometimes slip suddenly, causing strong earthquakes. Aside from this, evidence of their existence is less obvious. There are no mountains or volcanoes. If a paved road is broken, one stretch having moved ten feet away, this means the roads spanned the fault, an earthquake happened, and now the road will never connect unless repaved. We needn’t consider this when drawing continents.

The post Understanding Plate Tectonics appeared first on The Art of World Building.