Randy Ellefson's Blog, page 28

October 1, 2018

The Moon and Tides

Tides are variable. They are affected by coastline, currents, and other factors we can usually ignore as world builders and writers. But the moon is the greatest cause of tides, followed by the sun. If we want moons different from ours in number, proximity, or orbit, we should understand the moon’s effect on tides. On Earth, tides can be so extreme that boats moored at high tide are sitting on the beach at low tide, which is one reason large vessels remain farther out and small boats are used to come ashore; such situations could be exaggerated with additional moons. Tidal forces are also causing our moon to get farther away, which would happen on any world we build (it if has oceans), but the rate is infinitesimal; still, a moon is unlikely to be getting nearer unless it’s already very close. Gravity will pull it in and rip it apart. This can be a very real doomsday scenario for a world because the moon’s debris will rain down on the planet’s surface and cause destruction; the planet’s tilt will also destabilize, affecting seasons and possibly causing dramatic and rapid-onset ice ages, for example (more on this in the next section).

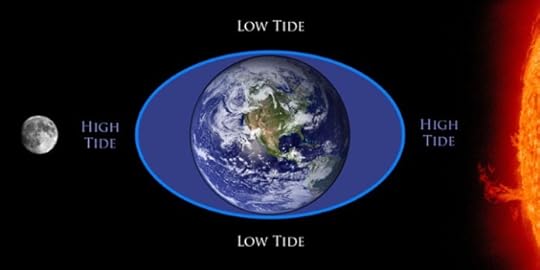

Our moon causes high tide on the side of the Earth it faces because it is pulling the ocean away from the planet. The moon is also pulling the Earth that direction and away from the ocean on the opposite side, causing another high tide on the planet’s far side. The Earth’s other two sides experience low tide (see Figure 10 below).

Figure 10 Tides

This causes two high tides and two low tides per day. Those two high tides aren’t the same height, nor are the low. One reason is that the moon’s orbit is not perfectly circular. If we invent a moon with a more elliptical orbit, the tide will be less pronounced when the moon is farther away. Imagine your characters being aware that such a moon is coming close in a week and they must get to higher ground or be flooded where they are, and that many settlements have taken this monthly flooding into consideration.

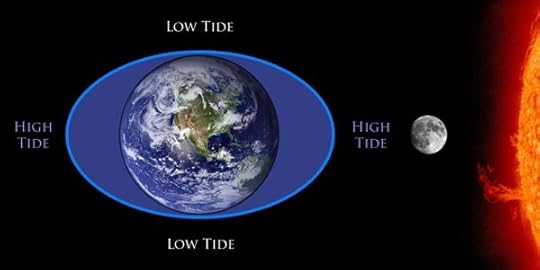

Among high tides, the highest tides are when the moon, sun, and Earth form a straight line, such as Moon-Earth-Sun. But the very highest tides are when moon and sun are on the same side, such as Earth-Moon-Sun (See Figure 11 below), because the gravity of both moon and sun are most strongly affecting the same side of the Earth. This is called a “spring tide” but has nothing to do with the season—it occurs twice a month, as does the corresponding lowest tides, called “neap tides.” On a world of our invention, we might want to rename “spring tides” to avoid confusion.

Figure 11 Highest Tides

A moon’s diameter (apparent size) isn’t particularly relevant for tides. Rather, mass and distance from the planet are the primary factors in tidal forces. Change either and we increase or decrease those forces and the resulting impact on a planet. More mass means more impact. More distance means less impact. Fortunately, our audience isn’t expecting us to tell them the mass of a moon or how far away it is, especially as compared to Earth’s, so we can usually ignore this, but we can at least know what we’re ignoring.

We’ll take a detailed look at how adding a second moon affects tides, as the observations can be expanded to additional moons and their impact. Using a clock face for orientation, with Earth at the center, what might the tides be like if the moons are:

the same mass

equidistant from the planet

at 12 and 3 (to start) and never get materially closer or farther from each other while orbiting?

Picture Moon One’s gravity pulling at the 12 and 6 positions (causing high tides there) while Moon Two’s equal gravity does the same to 3 and 9 (causing high tides there, too). Would they balance each other’s effect on the oceans, causing a constant water level (i.e., lack of tides)?

Unless we’re physicists, we can get ourselves into trouble with this kind of thinking, creating impossible situations. Is that’s why it’s called “science fiction?” Not really. SF is fiction which combines science that does not exist while hopefully getting right science that does (italics) exist. We have leeway to invent but should aim for believability.

Lack of tides isn’t particularly useful, interesting, or likely (without mutual tidal locking; see previous section). The theoretical scenario above is a starting point for making observations that can help us make informed decisions. Altering that example, if two moons are at 12 and 6 and stay that way (always on a planet’s opposite sides), we’d have more extreme tides. But if one moon had lower mass, it might have less impact on tides. This would also be true if one moon was farther away. Or had a more elliptical orbit.

Only distance, not mass, affects orbital speed. More distant satellites orbit slower, so two moons at different distances can’t stay on the planet’s opposite sides. Having two (or more) moons that are always in the night sky at fixed points to each other is unlikely. The nearer moon, moving faster, would appear to regularly catch and pass the farther moon. This will sometimes cause them to align in the sky. If they’re orbiting in the same plane (and most moons of a planet do), this will cause at least a partial eclipse of the farther moon by the nearer. The degree of eclipse is determined by the relative size, not mass, of the moons. For a total eclipse, the nearer one must be large enough (as seen from the planet) to completely block the farther one as seen from the planet.

An elliptical orbit would also mean that a moon’s effect on the world would ebb and flow depending on how far away it was; imagine it coming close once a month and causing a much stronger tide, and if this coincided with being on the same side as the other moon (and sun) every year, maybe we’d get a far stronger tide once a year.

If two moons are orbiting at different speeds (they do not stay at 12 and 6 in relation to each other), they can only do so at different distances from the planet. Otherwise they’d have crashed into each other, resulting in one merged moon and possibly a ring around the world from the impact’s debris. The falling remnants would wreak havoc on life. If the moons are at different planes (but the same distance), they could theoretically survive, but gravity would eventually draw them into a collision because orbits stabilize to the same plane in time. This is a potential doomsday event for inhabitants.

When the two orbiting moons form a straight line with the planet, the tide would be more extreme. Otherwise, tides would be weaker.

In the most likely case of two moons orbiting in the same direction but at different speeds, at different distances, we could decide how long it takes for each of them to orbit the planet. We can just pick a number. Keep in mind that a number less than Earth’s moon (which orbits in 27 days) means our invented moon is that much closer. A moon orbiting in 14 days is about half as close, when our moon is already very close. Anything that close will have a big effect on the planet, so unless we really want to emphasize the moon in some way, have the moon equidistant to or farther away than ours.

If our world has thirty days in a month, maybe we choose thirty days for one moon’s orbit. Then decide how fast the other moon orbits. With this decided, we can then figure out how often they’re on the same/opposite side of the planet. The formula is:

(P1 * P2) / (P2—P1) = C

P1 is the period that the closer moon takes to orbit the planet. P2 is the farther moon’s orbital period. C is the conjunction (when they’re together), though this could be any two relative positions. Assigning P1 to 15 days and P2 to 30 days, we get this:

(15 * 30) / (30—15) = 30

Breaking it down, 15 times 30 is 450. This is divided by the result of 30 minus 15, which is 15. So 450 divided by 15 is 30. Every 30 days, the moons will be in conjunction (or any other configuration).

If you’d rather not do these calculations manually, the “Moon Orbit Calculator” Excel spreadsheet included with the free templates allows you to type in the number of days for two moons and get the answer. If we’re after a certain result, we can keep changing the numbers until it produces an answer we like.

For example, on my world of Llurien, there are 28 days in every month (because there are 28 gods and each gets a day). I want the nearest moon to orbit in 28 days, heralding the start/end of each month. Three months is a season of 84 days. Each season, an arrangement of gods changes. I wanted a conjunction of moons to occur each time, adding increased significance to this seasonal event. That means a conjunction at 84-day intervals. So how long does it take for the second moon to orbit? I probably could’ve used math, but I just kept typing numbers into the spreadsheet until 42 for moon two’s orbital period caused the conjunction field to say 84, my goal.

Knowing when two moons coincide can help us determine how often eclipses happen. It also tells us when the highest tides are. Sailors and port townsfolk will be aware of this. A water-dwelling humanoid species might be, as would animals, both on land and sea, possibly taking advantage of this during birthing, hatching, or forays ashore.

This exercise can be imagined with more than two moons, though you’ll have figure out the formula for that. Effects on the planet start getting complicated unless we keep most of the moons farther away, give them less mass, and keep them in a mostly circular orbit. All of this reduces their impact so that we can include them, but concentrate on the influence of the one or two most influential moons have on tides.

What happens if there’s no moon? Probably very little tide; the sun would cause some tides.

The post The Moon and Tides appeared first on The Art of World Building.

September 27, 2018

The Moon and Tidal Locking

Earth has a stable moon with no atmosphere, but other moons in both our solar system and beyond are volcanic, icy, or have toxic atmospheres. While our moon is relatively large in relation to the planet it orbits, and has a steady, close orbit, satellites orbiting other planets are often smaller, farther away, and have eccentric orbits. Most solar system objects orbit in the same direction, but some are backwards. This retrograde motion usually means a moon (or a planet) formed elsewhere and was captured by the planet (or sun). By contrast, a moon that formed when the planet did will orbit in the same direction. Large moons tend to match the direction while smaller ones can go either way.

Tidal Locking

The term “tidal locking” will make many of us think of tides, but these are unrelated phenomenon. Our moon is tidally locked to the Earth. The same side is always facing us because the moon rotates on its axis in the same number of days it takes to orbit us. This might seem coincidental and unique, but most significant moons in our solar system are tidally locked to their planet; those nearest experience this first. Tidal locking is an eventual result caused by gravity. Early in a moon’s orbiting, it might not be tidally locked, but ours may have become locked in as few as a hundred days (it’s proximity and size having much to do with this). A moon that is not tidally locked may have recently formed or been captured by the planet. Either way, the stabilization process hasn’t completed.

As world builders, we have some leeway to claim a satellite is locked or not. Most people are unfamiliar with the concept and we should only mention it if locking has occurred, as readers will assume the opposite without being told. Note that a close, large moon like ours will almost certainly be locked; during the brief period when ours was not, it and the Earth were molten and devoid of life.

Normally, only the satellite is locked to the planet, but they can become mutually tidally locked, as happened with Pluto and its moon, Charon. This means that each of them only sees one side of the other. If we stood on our moon, we’d see all sides of Earth as it rotates, but from Earth, we see only one side of the moon because they are not mutually tidally locked. If they were, the moon would stay in the exact same spot in the sky. About half the planet would see it, while the other half wouldn’t even know it existed unless traveling to the far side of the world. This would eliminate most tides (see next section) except those caused by the sun.

We can create a planet that orbits the sun in the opposite direction from other planets, a fact which would likely be noticed. In a less technological setting, supernatural significance might be attributed to this. In SF, perhaps inhabitants of that planet realize it originated from another solar system and wonder what it’s doing here. Where did they come from? We can also create a captured moon that orbits in a different direction than the planet or its other moons; these are typically farther away because gravity will eventually change that for nearer moons.

The post The Moon and Tidal Locking appeared first on The Art of World Building.

September 24, 2018

Creating a Planet

There are global issues to consider in creating a planet, such as moons, climates, the sun, and the rest of the solar system. Unless we’re planning to do something truly unique with any of these, like two suns or moons, we’ll probably want to go with an Earth-like situation, which is the focus of this chapter.

However constant celestial bodies appear to us in our limited lifetimes, their relationships are always in flux. We can invent a scenario that isn’t likely in a four-billion-year-old solar system, but which is possible in a two-billion-year-old one. The reason is that gravity slowly stabilizes relative positions. For example, gravity causes satellites to eventually orbit in the same plane. If we have them in two different planes, we’re implying the solar system’s youth. Either that, or one of those moons was recently captured by the planet and hasn’t stabilized with it yet. By “recently,” we’re talking in billions of years, meaning this happened well before our species crawled out of the ocean.

This may give us some leeway to invent a situation lasting long enough to tell our story, at the risk of eye-rolling by physicists. One goal of this chapter is to reduce such reactions and make reasonably informed decisions. Fortunately, physicists make up a relatively small percentage of Earth’s inhabitants. Unfortunately, they make a far higher percentage of science fiction readers!

Some ideas and terms apply to more than one section of this chapter. The alignment of three or more celestial bodies into a straight line is a called a syzygy. An eclipse is one type. Another type, called a conjunction, is when celestial bodies appear to be lined up from a low point in the sky to a higher one, as seen from another location (like Earth’s surface). The term conjunction might be familiar to fantasy fans, as this has been used in stories, such as the films The Dark Crystal and Pitch Black, to indicate a rare aligning in the heavens, one that portends a great event. This is usually when some poor schlep is sacrificed, for example.

Appendix 1 is a template for creating a solar system and its planets, moons, and other satellites. It includes more comments and advice, and an editable Microsoft Word file can be downloaded for free by signing up for the newsletter at http://www.artofworldbuilding.com/newsletter.

Rotation

Our planet is either rotating clockwise or counterclockwise. The Earth does the latter, which is why the sun rises in the east and sets in the west. We can reverse this for a quick way to thrust our audience into a different perspective. Of course, the stars, planets, and constellations will also travel across the sky in the opposite direction. Be aware that this affects ocean currents, covered later in this chapter. For world builders, this affect is largely that of which coast of a continent has warmer or colder waters. Prevailing winds will also be reversed in each hemisphere.

The Sun’s Impact

Our lone sun is technically a yellow dwarf star of medium age. Most world builders, particularly in fantasy, will just want to go with the same and call their work done. More extreme situations might be better suited for worlds we’ll only use for one story. In SF, with characters traveling across the cosmos to various planets, the viability of life in other suns’ solar systems is debatable.

For example, a planet in the habitable zone of a red dwarf star would experience tidal locking (the planet’s same side always faces the sun, just as one side of the Moon always faces Earth). This causes perpetual night on one side and perpetual day on the other. This sounds cool at first until we consider the huge temperature variations that would make Earth-like life difficult or impossible to form.

A moon orbiting such a red dwarf’s planet could sustain life if it was also tidally locked to its planet, because that would cause the moon to not always have the same side face the sun. Even so, the lack of ultraviolet light also makes life unlikely, as does the variable energy output from the red dwarf (our sun is relatively stable). Maybe life can’t originate there, but there’s no reason we can’t put a mining or research colony there. We can use such worlds but maybe not have much life originate there unless that life is extremely different from Earth’s.

The post Creating a Planet appeared first on The Art of World Building.

September 20, 2018

Where to Start with Kingdoms

We should first decide on a purpose for our sovereign power. Is it to be a force for good or evil? With that decided, choose a government that influences this disposition; more freedom for people is typically good in many ways while less is bad in many others. Next we should decide where on a continent it lies, as this will determine neighboring powers and what land features are near, which in turn affects who lives here; if our power covers a wide area, species’ distribution will vary by location. With population so important, it’s a good idea to decide on the general makeup of the residents. Are they 40% human, 20% elf, 15% dwarf, and the rest a mix of dragons, ogres, and whatever else? Now that we know who lives here, determine the power’s relationships with its own people and other locations. This has a huge impact on our world building and could arguably come first when inventing a power. Remember that everything in this book is a recommendation but there’s no right way to world build. Finally, we can attend to lesser issues like identifiers, language, and customs.

The post Where to Start with Kingdoms appeared first on The Art of World Building.

September 17, 2018

Ways to Identify a Power

A sovereign power is keenly interested in symbols, flags, and even slogans that are associated with it; this is also true in a feudal society. Although outsiders can stigmatize a place by associating it with something undesirable, this section focuses on inventing identifiers a power has chosen for itself. The goal of an identifier is to embody and portray a fundamental trait of a sovereign power. As such, the identifiers acquire power. They can inspire love, loathing, and indifference. They can be a rallying cry for resistance in war. They should not be overlooked. With travel such an elementary part of SF and fantasy, our characters will be looking for them when approaching space stations, ports, and fortifications. Failure to mention one is an oversight.

Despite all of this, world builders may need to invent them later in the process of creating a sovereign power when our idea of a place is more firmly established in our minds.

Symbols

A sovereign power often has a symbol, which its reputation may influence. Symbols may change when the government does to signify the change to outsiders and a country’s own people. Inventing a symbol allows us to emblazon it on flags, ships, buildings and more.

To invent a symbol, we should decide how our sovereign power wants to be viewed by its citizens and by outsiders. An authoritative government will have a more intimidating and bold symbol (and colors) to imply oppression and dominance. A show of strength might be desired, either to intimidate potential attackers, or to bolster itself against a sense of weakness. A democracy might want to appear more inclusive and benevolent. Some symbols are negative like the skull and crossbones of pirates, while others show unity, like the United States flag and its stars representing each state. A symbol might not accurately reflect the power.

If we choose an animal to represent the power, this animal doesn’t need to be specific to the landscape there, or even be found there, particularly if it’s considered a wide-ranging animal. This is also true of plants. However, a distinctive landscape feature like a mountain with a peculiar peak should be located within the territory; for inspiration, consider Crater Lake, the Matterhorn, or the Devil’s Tower. Other symbols can be based on the sovereign power’s reputation (see the section in this chapter), regardless of which came first.

When deciding on a symbol, we should remark upon the impression it creates. If we’re an artist, we can draw a hawk that looks vicious or that appears noble and proud. Simply saying it’s a hawk doesn’t convey this important distinction. While implying an impression can be fine, the ambiguity leaves room for uncertainty—and a sovereign power typically wants to be quite clear with its symbolism.

Colors

While black or white colors can be used for identifiers, other colors can be used to increase the impression an identifier creates. Domineering governments often choose bold primary colors. The black, white, and red of Nazi Germany springs to mind. Benevolent countries might choose softer and lighter shades of colors like yellow and green. While this approach can yield results, it is unrealistically simplistic. Usage is everything. Don’t be afraid to use colors for no apparent reason. We needn’t tell the audience what each color represents, assuming it represents anything. They’ll care about the impression it creates. The meaning of colors will be lost upon us unless explained, and explanations are best avoided unless done quickly and artfully.

When choosing and creating sovereign powers, try to prevent too many of them from having the same color combination. Having a list of them will assist with this. Organize the list by continent, region, or alphabetically.

Flags

Flags often include the symbol in the power’s colors, but not always. Many flags are quite simple, being strips of colored fabric. In a world with less technology, flags should be simpler to produce because they’re likely being made by hand. This doesn’t mean they need to be three strips of colored cloth sewn together, but simple geometric shapes are helpful. There are talented seamstresses who can embroider something extravagant, but this takes longer and there aren’t as many of them to do the job. In SF, more elaborate flags (and symbols) might abound because machinery can crank them out.

On Earth, we often don’t understand why a flag has its design unless it’s from our own country. In SF, with so many things to distract us, we might tend to care less about such things, but even in fantasy, fewer people will know, or care, about a flag’s design. This gives us some leeway to invent without much justification. To make life easier, it’s recommended that world builders decide on a symbol and place this on a flag, killing two birds with one stone.

Slogans

Our power might have a slogan associated with it. These are short, memorable phrases that epitomize a fundamental aspect of the sovereign power’s outlook. They can inspire greater passion, loyalty or fear, such as “Resistance is futile” by the Borg of Star Trek, though the Borg aren’t really a sovereign power as we think of it. Games of Thrones used this to good effect (“Winter is coming”) and so can we. Inventing this calls on our skills as writers to sum up a truth in a catchphrase. Like the other subjects in this section, it requires knowing what our power is all about.

Reputation

Our sovereign power is likely associated with certain traits. These can include basic quality of life and freedoms (or the lack thereof), but we might want something more specific, such as an item from this list:

A mad king

Slavery (this includes being the source of exported slaves)

A space craft design or type of man-o-war

Raiders (like Vikings) or conquerors (maybe a specific individual like Genghis Khan)

Wizards being banned

Unique plants, animals, or products

An unending war, either internal or with another country

The first place something happened (a launch into space, a discovery, an invention)

A horror, whether supernatural or technological

Superior weapons, armor, technology, or other devices/items

Nomadic tribes with expert horsemen

A seafaring or spacefaring superpower controlling territory

Being near the elven homeland (or any other species, pleasant or not), and having good/bad relations with them

Make a list of options you’d like to cover and begin assigning them to the powers you create. Using Earth analogues makes this easier. Remember to change details and mix and match traits to obfuscate the source; see Chapter 1 from Creating Life (The Art of World Building, #1) for why. These issues don’t have to dominate a nation, but they can be good starting points we expand on.

To get started, consider geography and government. For example, a naval or spacefaring superpower will need ship builders and might export ships to other countries. A seafaring one might be an island nation that excels at fishing and facing sea monsters, with legends, myths, and famous sailors. Animals or plants from the sea might be harvested. They probably also have a history of colonization attempts. Where am I getting some of this from? Great Britain.

The post Ways to Identify a Power appeared first on The Art of World Building.

September 13, 2018

Tension within a Kingdom

Whether a sovereign power is physically isolated (like an island) or borders other nations, it will have allies and enemies who shape the past and present due to tensions. In the early stages of building a world, it’s best to focus on the high-level aspects of these relationships, such as who is friend or foe. If we don’t have a reason for our decisions now, we can add it later. There are some basic reasons we’ll cover, however.

Ethnicity

Ethnic hatred and other forms of racism are an unfortunate reality. We can pretend they don’t exist in our world, but if so, that’s best done by never commenting on it, not explicitly stating it doesn’t happen, as this strains credibility. If we choose to invent this sort of tension, understanding the source helps. Generally, unfavorable attributes are assigned to a group of people who often share physical traits that make them more easily identified on sight; this is part of where the superficial aspect of this enters. Don’t use only skin color for this, as facial features like eyes and noses can be used, too, such as how Asian and Jewish features have been on Earth.

The source of that unfavorable trait can be cultural, ideological, or based on government. For example, people living in an authoritative state might despise people in a relatively free democracy. This can be jealousy but is more likely to be propaganda put forth by that authoritative state condemning democracy and vilifying various aspects of it. Those in the democratic power might have similar negative views in return. Even if these governments change in time, the character assassination will linger (on both sides). These ideas are attached to the people.

In practice, borders change and people move, resulting in a mix of ethnicity that leads to conflict. This can cause one kingdom to attempt exterminating or expelling those of a different ethnicity. While we see this with humans, it can be done with other species, like elves against elves, or between species, like elves expelling humans from conquered territory.

This sort of expulsion can lead to perpetual war, particularly if cherished ground lies in contention. Jerusalem comes to mind. Retaliation can linger so long that each is convinced the other struck first or that they can never let an action go unanswered. The original reason for conflict can be lost to antiquity, which gives us some leeway to invent a conflict and a current claim by each side that justifies its stance, without worrying about having it “right.”

We might feel that some of our species and powers are more enlightened than this, and they may well be, but racism can still run deep and be hard to eradicate.

Resources

Natural resources can cause tension when sovereign powers can’t share them peacefully. This can happen when one power has the resource entirely within its territory or if the resource spans both powers. Newly discovered resources might cause a struggle to possess it. Weaker powers might also control a resource only to be threatened by a stronger one. While Earth-like resources are fine, materials of our invention can include items needed to power space ships and weapons, cast spells, heal people, or anything we imagine. Rarer resources are more valuable and we can decide what’s common on our invented world, but try to avoid making gold, for example, largely worthless, and something that’s cheap on Earth be prized on your world; this tends to confuse and it might be better to just create a new resource than to do this.

Territory

There are many reasons territory can cause tension. This includes resources located there, ethnicity (discussed above), religious significance, and the access the territory provides to other destinations. In the latter case, a landlocked power might wish to conquer another to gain access to the ocean. Territory sought is typically held upon acquisition unless something prevents this, such as the conquering army losing so many of its troops in victory that it cannot hold what it has gained. It might also become vulnerable to threats from elsewhere. Such fears can keep an invasion at bay unless something tips the balance. It might also succumb to local disease to which it doesn’t have immunity.

World View

Ideological differences can cause one power to want another’s destruction or to become allies against such threatening powers. These differences may be not only political, but cultural, religious, and moral. Some populations, or at least their government, want to impose their own way of life on others, and see differing ideologies as a threat. This is one reason the United States supports struggling countries and why Russia supports different ones. The resulting conflicts are proxy wars where two superpowers are fighting each other via smaller countries they seek to influence. This can make for strange allies.

Internal Conflict

In extreme cases, internal conflicts can lead to rebellion, civil war, or government collapse. These dramatic events are useful in creating not only history, but a current situation that embroils our characters. A story taking place during such events is often about those events, however, so if doing this, we will need to work out the details of the conflict. If we don’t want to focus on such extremes, then lesser tensions might be needed. These less dramatic issues can eventually reach the extremes we avoid until later, if at all. Don’t be afraid to set these stories in motion out of a desire not to deal with the result now.

The conflict often involves freedom, abuses by government, or basic needs not being met, such as infrastructure or economic failures. It can be ideological in that people have lost faith in a leader or what he stands for. These reasons often merge, such as when slavery led to the American Civil War. This was both ideological and economic, as the south’s economy depended on slave labor that the north wanted to abolish for ideological reasons.

The post Tension within a Kingdom appeared first on The Art of World Building.

September 10, 2018

Kingdoms and Location

This section discusses how the climate of a kingdom can be largely decided for you if you’ve already created a map.

The post Kingdoms and Location appeared first on The Art of World Building.

September 6, 2018

Location Matters with Kingdoms

The adage that “location is everything” applies to an entire sovereign power. This determines climate, neighbors, and what natural resources are available (and which are not). The form of government will have little to do with location, however, as anything can exist anywhere.

Despite the latter, creators sometimes allow landscape to influence or characterize a power. If we desire this, then mountainous areas are good for an authoritative state and an impregnable fortress or city. An island nation lends itself to being a seafaring power that raids other lands, but it can be democratic or authoritarian. A desert’s foreboding landscape can be good for authoritarian states, but then so can an area heavily forested enough that travelers must struggle through the vegetation.

If none of this seems definitive, that’s because we can make a case for anything if we characterize it right. When we desire a desert dictatorship, just claim the harsh landscape inspired it. Imagination gets us whatever we want and helps avoid oversimplified clichés. If we’ve already decided on our government type, we can consider this, or not, when choosing a region to place it in.

Having a map while inventing a sovereign power is advantageous (mapmaking is covered in Chapter 12). This allows us to place the capital somewhere and know where borders, other settlements, and land features are. If we don’t have a map yet, then use a piece of paper to sketch regions as ovals marked with the land feature type, like “forest.” We can also draw an arrow off the page and indicate an ocean or a dictatorship lies that way. Colored pencils can help; drawing a jagged coastline isn’t much help if we can’t remember which side the water is on. Use blue for water, green for forests, yellow for desert, and brown for mountains.

Having a sense of the sovereign power’s overall disposition (benevolent vs. domineering) can lend ideas for the land features we might like there. This includes how those land features are characterized. A foreboding forest or mountain range might suit one need while a pleasant, coastal savannah with numerous islands offshore might suggest another use. If you have a map, look at it for possible areas to include within the borders and what features might be contested by neighbors. If you don’t have a map, you can sketch it using the same mindset.

Decide on the overall territory and where current borders are. Leave room on a map for other sovereign powers, being aware that the more land this one takes, the less there is for everyone else. This is a greater issue if our map already exists and we don’t want to alter it. Country boundaries on Earth make little sense to most of us, suggesting we can do as we please, although major rivers often form boundaries, as is the case in the United States with the Mississippi River.

The post Location Matters with Kingdoms appeared first on The Art of World Building.

September 3, 2018

What Customs Are in Your Kingdom?

These section talks about determining the customs found in a sovereign power you invent.

The post What Customs Are in Your Kingdom? appeared first on The Art of World Building.

August 30, 2018

What Languages Are in Your Kingdom?

Decide if this power has its own language, which will often be named after it; sometimes the power’s name changes, but the language’s name doesn’t, a minor detail that adds depth if we have occasion to mention it. Even if many cannot read and write it, a written language will almost certainly exist. Higher forms of governments arguably require it.

Secondary languages can also be widespread. These may originate from other species. The language of neighboring powers will be spoken by some people but isn’t something we need to consider unless these languages are widely spoken. The presence of other languages could bother those in power to the point of suppressing them, as an authoritative state might. Writings in other languages might also be banned. In extreme regimes, reading and writing might be withheld from the population to keep them ignorant. We should decide whether areas bordering other lands have secondary languages or not.

Humanoid species are often widespread enough that territory isn’t the deciding factor in whether others know the language. Rather, personal experience with that species will cause most people to pick up some words. In such a case, understanding will be limited instead of deep and broad; this is known as a working knowledge of language—enough to get by on the streets but not hold deep conversations. In more educated worlds, a language could be taught in school much as it is on Earth. This might be truer in SF, where education is generally assumed to be far greater than in fantasy settings, but we can challenge that assumption.

Fantasy often includes the concept of a common tongue, one that most humanoid species can speak well. This concept is useful on film, reducing the need for subtitles at the least, but it also frees authors from inventing languages. Despite the nomenclature “common tongue,” not everyone will truly be fluent, as barbaric species are often depicted as being barely coherent. Anatomy sometimes causes this. So can the common tongue diverging too strongly from their natural language so that they sound guttural in speaking it. This common tongue will be the language of somewhere. When choosing a name for it, we might first want to consider what empire of the past conquered so much of the world that its language became the common tongue.

In SF, language is rendered moot by universal translators. Characters are unlikely to learn other languages unless for curiosity’s sake or because the equivalent of Starfleet Academy from Star Trek demanded it of officers. In the event of a universal translator failure, our characters may be unable to communicate with alien species at all without said training. It seems reasonable that on a large ship, at least one person would be fluent without the devices, not by chance, but due to protocol. A ship’s A.I. would serve the purpose, but that can be comprised. The machine translators are typically not present onscreen but are portrayed as largely infallible when that’s unlikely to be the case. Subtle nuances are lost on even people, let alone machines. Relying on just the words and not the tone or body language of the speaker is also problematic.